New York’s 2020 Census Victory - How It Happened & What’s Next

NYC Census efforts (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Despite concerns that the 2020 Census count in New York City would reflect a major minority undercount and leave out people who left because of the pandemic, we came out on top.

The results of the Census were outstanding for the region. After decades of alleged Census undercounts, the New York City saw its population grow by 7.7% since 2010.

And it’s even more remarkable given unprecedented challenges posed by the pandemic and the Trump administration. Census counting was delayed by several months. Then-President Donald Trump also tried numerous times to subvert the Census count by trying to add a citizenship question, later struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court after the administration failed to follow standard government procedures, though concerns over such a question led many immigrants to shun the Census over fear of arrest or deportation. Trump also cut short the Census counting period by several weeks and attempted to adjust the final state population counts for partisan purposes.

How did New York City do it? By coming together to get out the count.

Mayor de Blasio and the City Council committed $40 million to Census outreach efforts. Groups including the Association for a Better New York and the New York Counts 2020 coalition invested time and energy to grassroots outreach.

Also critical to the city’s Census “success” was the ability of the New York City Department of City Planning to add 265,000 housing units missing from the Census Bureau’s address lists so that every household would receive a Census form in the mail. This effort alone may have resulted in counting half a million city residents who might otherwise have been missed.

Every single one of these New Yorkers mattered. We cannot forget that the state lost two or three districts after each of the last three censuses, with one district lost this time because we came up short 89 people in the state population totals.

There are critical lessons that we must learn from how New York City was able to beat the odds and deliver a strong Census count, thanks to the heroics of grassroots organizers and city leadership.

The Census has now been politicized like never before, with the Trump administration openly attempting to sabotage the count. New York must keep the infrastructure we have developed in place for the next time, and add to it, especially at the state level.

Early planning and investment is critical, and we cannot wait until the year before the 2030 Census to get ready. Our governor, mayors, legislators, and other elected officials must invest in ongoing demographic studies to gauge population shifts. State and local complete count committees need to be organized several years in advance and must receive adequate funding.

It’s mind-boggling to think of how much better a Census count New York might have had if well-funded efforts ramped up much earlier. California invested over $90 million for Census efforts and helped stave off the loss of several congressional districts. Minnesota’s well-organized private-sector efforts helped prevent the loss of one congressional district by 26 people.

For the next Census, New York should be able to keep all of its congressional seats.

Right now, New Yorkers should turn their attention to the state’s new Independent Redistricting Commission, a body created by a 2014 state constitutional amendment that took the initial district line-drawing responsibility from the Legislature to make the process more transparent and participatory.

The commission, appointed largely by the state’s legislative leaders, recently completed a “listening tour” round of public hearings via the Internet to hear from New Yorkers on the kind of districts they want to see in place for the 2022 elections and through the 2031 elections. The commission asked for New Yorkers’ ideas on how to draw districts using “communities of interest,” basing districts on shared economic, social, religious, social, and other neighborhood factors. Other factors that must be considered include population equality and fairness to minority voters, compactness, contiguity, and partisan fairness. The criteria also suggest consideration of the cores of current districts.

The commission is targeting mid-September to release its draft congressional and state legislative maps. Another series of statewide public hearings will follow in October. New Yorkers should let the commission know what they think of the draft maps at those hearings before final maps are sent to the Legislature for approval or modification at the end of the year.

While we won’t know how the final lines will be drawn, for the first time in a long time, we know that the state’s population is more diverse and still growing at a time when it is most needed.

***

Jeffrey M. Wice is an Adjunct Professor at New York Law School and Senior Fellow at the school's Census and Redistricting Institute. On Twitter @JeffWice.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Next New York City Administration Must Prioritize Youth Voices

Engaged youth, New York City (photo: Paige Polk/Mayoral Photography Office)

As CEO of Big Brothers Big Sisters of New York City (BBBS of NYC), the nation’s first youth mentoring organization, I hear from young people nearly every day. I’m consistently impressed by their thoughtfulness, bravery and solutions-driven creativity. Each of our Littles has a unique perspective, but I’ve heard one consistent gripe over this last year: They want us to listen to them!

It’s remarkably disheartening to continuously see the city’s leaders not heed the voices of our youth. But, there is an important opportunity for change.

We need the next New York City government administration, due to take office in January, to prioritize the ideas of New York’s youth, and implementing a city-wide youth council is a wise place to begin.

Rather than the multiple Youth Leadership Councils currently in operation, this single body could be endorsed and sponsored by the next mayor and give the youth of our city a chance to meaningfully influence policy ideas.

Nearly 1 million New Yorkers voted in this year’s primaries, the highest participation in a local election since 2013. This came after New York City officials sought to double the turnout of registered voters aged 18 to 29. It’s clear more New York City youth want to vote and have their say in government. It’s less clear that New York City politicians and public officials are listening to them.

Resources to public schools ranks among the biggest issues for young New York City voters, yet mayoral candidates Eric Adams and Curtis Sliwa -- the Democratic and Republican nominees, respectively -- have talked more about across the board budget cuts. The next mayor of New York City needs to go the extra mile and create a platform for youth to ensure their voices are heard and their suggestions are heeded.

BBBS of NYC has its own youth council to function in a similar fashion. In fact, it was created at the suggestion of the youth themselves. They’ve pushed our organization to make impactful changes, including advancing LGBTQ inclusion throughout the organization. I envision a citywide youth council operating in a similar fashion.

If we are serious about getting youth more engaged, we would be foolish not to listen to them. By incorporating youth voices alongside our city’s leaders, we fill an important gap in our policymaking process.

All levels of city government and planning too often take young people’s voices for granted. I’m both a parent and a youth mentoring executive who is still dumbfounded that youth were excluded in planning the 2022-2021 school year. Why wouldn’t we consider the voices of the people most impacted by these decisions? Let’s make certain that the 2021-2022 school year is shaped differently through the viewpoints and informed experiences of its students. A city-wide youth council representative of the extraordinary diversity of New York City gives an important yet long ignored constituency a voice and seat at the table.

This isn’t just my idea. Youth across New York have made it known they want to have a say in the city’s future. A recent survey from Citizens’ Committee for Children found that 40% of respondents ages 14 to 24 believe they have a say in how our government runs. These are youth who want and believe they have the power to influence change. I’ve seen this same passion and optimism from the participants in BBBS of NYC’s youth council.

Consider Jena, a young Korean woman on our youth council. Over the last year she has struggled to adapt to remote learning, frustrated over being tested on lessons she felt she was never taught. At the same time, she dealt with the anxiety associated with being an Asian woman amid increasing xenophobia and violence. A city-wide youth council offers Jena a chance to speak directly to the next administration about what concrete steps are needed to protect the Asian American Pacific Islander community. With youth unemployment hovering around 12%, higher than the overall rate, it also gives Jena and her peers a chance to advocate for opportunities beyond programs like the Summer Youth Employment Program (SYEP).

Mayor de Blasio has said young New Yorkers are poised to play a “pivotal role” in the city’s recovery from the pandemic. I couldn’t agree more. I challenge the new administration to do more to fulfill that promise and finally give New York City’s youth the chance to have a real say in their future.

***

Alicia Guevara is the Chief Executive Officer of Big Brothers Big Sisters of New York City. On Twitter @BBBSNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Downstate Population Gains Mean State Legislature Power Shift No Matter Who Draws New District Lines

New York State Senate (photo: NY Senate Media Services)

The United States Census released the nation’s population data by congressional and state legislative district on August 12, setting underway the re-districting of legislative seats, controlled by each individual state. The process will now unfold in New York and around the nation, with control of the House of Representatives and state legislatures on the line.

Having served in the New York State Legislature for 32 years, I went through three redistrictings, in 1992, 2002, and 2012.

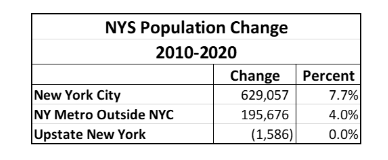

Major internal population shifts within New York State have profound implications for redistricting. New York gained about 823,000 people, an increase of 4.25%, between 2010 and 2020. All of the growth was downstate, as discussed in an outstanding summary of New York’s changes by John Bacheller, and shown in brief here:

This significant population increase downstate compared to Upstate likely means a decline in the power of the Republican Party in New York. Its power base has been Upstate, and,until recently, Long Island, and this redistricting cycle marks the end of GOP control of the lines of State Senate districts, which it held through most of the twentieth century, and for 2002 and 2012.

Additionally, since 2012, the year new district lines were put in place in New York based on the 2010 U.S. Census, New York’s redistricting structure has changed. A 2014 Constitutional Amendment created an Independent Districting Commission. New York is now one of 13 states across the nation that have such a commission. It will have the initial authority to draw the district lines for New York’s House seats and the seats in the Assembly and Senate.

The commission has already held public hearings and, in fact, commission staff confirmed to me that the first preliminary maps from the new body will be made public on September 15, 2021. The commission, whose members consist of equal numbers of Democrats and Republicans, along with several members jointly selected, is designed to draw fair districts and avoid partisan gerrymandering. It must produce maps no later than January 15, 2022.

If the commission fails to produce maps, or if two-thirds of both houses of the State Legislature reject the commission’s maps pursuant to a schedule over this coming winter, the Legislature has the power to draw new lines that must be signed by the Governor.

Since the 2014 constitutional amendment that was approved by voters and created the commission, Democrats gained a two-thirds majority in the State Senate, and kept the one they already had in the Assembly. Those majorities will await commission action, or inaction. Whatever changes they make to lines drawn by the commission are, of course, subject to court challenges.

Another constitutional amendment changing elements of the redistricting process is on the ballot in the November general election this year. It would speed up the timetable for approval and alter the threshold for the Legislature to reject the plans and draw its own lines, a change that is currently moot since in the intervening time the Democrats secured the double two-thirds majority.

During the 2012 redistricting, Republican and Democratic majorities controlled the redistricting process for the respective legislative houses where each held a majority of seats. The Democrats have controlled the New York State Assembly since they won the majority in 1974, and have had two-thirds majorities going back 30 years. The former Republican majority in the State Senate, however, had been under major threat for decades, and by the election of 2010 it held a razor-thin, 32-30 majority, to draw the 2012 district lines.

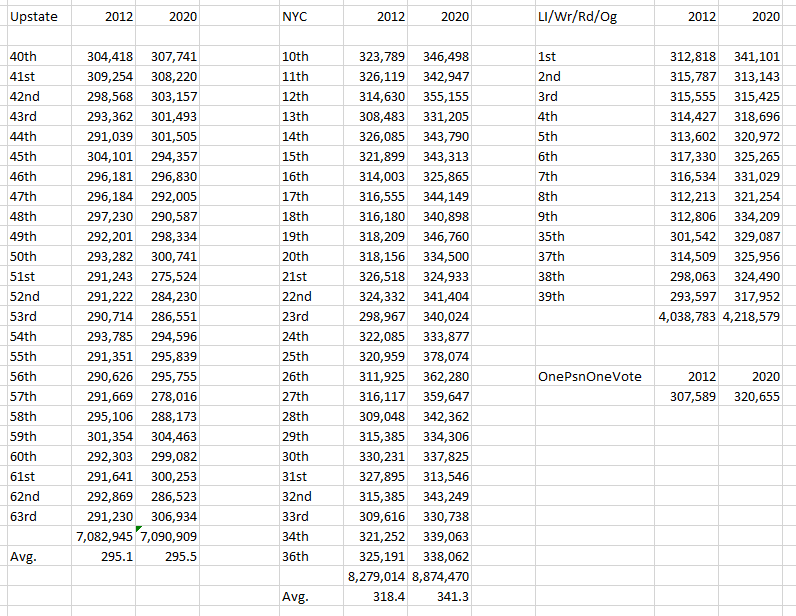

To preserve power, the 2011-12 Republican majority decided to create a 63rd State Senate district (an action permitted under the state constitution) in Upstate New York. The Senate Republicans’ goals necessitated putting smaller populations in the Upstate Senate districts than in the rest of the state. The drawing of state legislative districts is unlike congressional districts, for which nearly identical one-person one-vote populations per district are generally required. The rules for drawing of state legislative districts have allowed fairly wide population deviations from a strict one-person one-vote standard.

In New York in 2012, the one-person one-vote population norm for each of the 63 Senate districts would have been about 307,589 persons. To squeeze out the extra Upstate district, Republicans brought down the Upstate district populations as low as just under 292,000 (see table below). By contrast, they created New York City districts that reached as large as 330,000 persons. By stretching the population deviations as much as they could legally, they took away a Senate district in New York City to create the 63rd district Upstate.

The table below shows district populations in the New York State Senate in 2012 and in 2020. On the left are 24 districts in Upstate New York, starting with the 40th district, most of which is north of Westchester County, all the way to the 63rd district in Western New York.

In the middle are 26 New York City districts, including two in the Bronx that extend into Westchester County. On the right are the 9 Long Island districts, as well as several districts in Westchester, Rockland, and Orange Counties.

At the bottom of the columns are the population sums for the various areas of the state, as well as the population averages for the districts in the separated areas, for both 2012 and 2020.

It’s always important to keep in mind the one-person one-vote standard that would create districts with even population totals. For 2012 that would be 307,589 New Yorkers per Senate district, and the new 2020 standard is 320,655.

Despite the effort of the Republican majority in 2012 to preserve power by dropping the Upstate district populations below the standard, the plan didn’t work. The Democrats won a 33-30 split. However, a faction of the Democratic majority, known as the Independent Democratic Conference (IDC), then aligned with the Republicans and helped them preserve power all the way into 2018, when they finally realigned with the Democrats. Six of the 8 IDC members were defeated in Democratic primaries that same year, and another has since left the Legislature. After the general election in 2018, Democrats had won 41 of the 63 seats in the Senate, and via the 2020 elections, 43 of 63, reaching a two-thirds majority.

The new districting commission’s mandate is to produce fair districts, and having every district virtually identical in population, a pure one-person one-vote, is as fair as can be. Given 2020 Census numbers the new norm is now a little over 320,000 persons per district, up from over 307,000 based on the 2010 Census. The populations of the Upstate Senate districts now have an average of 295,500, about 25,000 persons below the one-person one-vote norm of 320,655, or a sum of 600,000 persons, nearly two Senate districts. New York City districts have a surplus above the 320,655 standard of about 538,000, about one and two-thirds Senate districts. The Metro suburbs have the remainder. Effectively Upstate New York must lose two Senate districts.

In the New York Metro area there are only five Senate districts still represented by Republicans, four on Long Island and one on Staten Island. The other 15 are among the 24 that lie mostly north of Westchester and Rockland Counties. As Bacheller pointed out, the population losses even within Upstate New York are concentrated in the rural areas; urban metro areas gained 1.2% in population, rural areas lost -3.6 % of their population. That is reflected in some of the Upstate Senate districts with losses; six districts are now below even 290,000 in population, some even below 280,000. Five of these six districts with the lowest populations are represented by Republicans.

Some analysts predict the equal representation of Republicans and Democrats on the districting commission will result in the failure of the commission to have a majority vote in favor of a districting plan, thus defaulting to the Legislature (which could reject even a plan that had been voted upon). I served with two of the Republicans on the commission, Charles Nesbitt, who had been the Assembly minority leader, and Willis Stephens, a lawyer from Dutchess County who is a sharp debater.

Nesbitt was, and I am sure still is, a decent and gracious man. But will he and Stephens vote to wipe out two of the last remaining 20 Republican Senate districts in the state, or vote for any plan likely to eliminate even one? I don’t know the answer to those questions but the Republicans have tougher choices ahead than the Democrats. Even if the districts were drawn neutrally and fairly, the Republicans are likely to be the inevitable losers. If the Legislature draws the lines, the Democrats in the Senate might be motivated to avenge many a redistricting wrong from decades past, or just address the population problems to shore up their Upstate incumbents while consolidating the Republicans into fewer rural districts.

The population shifts will also add at least one more Assembly district in New York City, whether the lines are drawn by the commission or the Legislature. In the suburbs the increasing presence of diverse populations could also strengthen Democrats. Most of what the Assembly Democrats have to worry about is where to put their surplus districts and members.

The result of redistricting internally in New York will be to consolidate urban and suburban power; House of Representatives seats for Congress are more likely to be the scene of bitter conflict over the future of the Democratic majority in the House in the national midterms in 2022.

***

Jim Brennan was a member of the New York State Assembly for 32 years, where he chaired four committees. On Twitter @JimBrennanNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.