Fixing a Broken System

The national discussion of health care reform has huge implications for our state, and I believe it is critical that Congress and the president reach an agreement that moves us down the road to real reform. The heated rhetoric and spurious charges that opponents of any reform were making in August seem now to have quieted down a bit, and both houses of Congress are moving toward their own versions of a reform package. Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi released the new House leadership bill (the Affordable Healthcare for America Act, H.R. 3962), and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid is expected to release a new Senate leadership bill some time in early November. While I have strong preferences as to what needs to be in the final legislation, the good news is that some fundamental reforms that will address the most serious problems of our health care system are now under serious discussion.

It is important to remember why we are undertaking this exercise: The current system is not working. In New York, 2.5 million people, or 13 percent of the state’s population, do not have health insurance. The uninsured are overwhelmingly represented by groups like the poor (47 percent of uninsured adults in New York State have incomes under 200 percent of the federal poverty level), minorities (while 13 percent of whites are uninsured, 21 percent of African Americans, 23 percent of Asian/Pacific Islanders, and 31 percent of Latinos are uninsured), and immigrants (30 percent of the uninsured are non-citizens).

An Unacceptable System

Health care costs continue to skyrocket while millions go without any health coverage at all. To the extent that these millions receive care, it is through emergency rooms – after they are already far more ill than necessary – which is a horribly ineffective way to deliver services, both in terms of the health of the individual and of the cost to the system.

Critics of reform claim health care will be rationed under the new system while they fail to acknowledge that we have more rationing of healthcare in the United States now than anywhere else in the developed world. But since that rationing occurs under the guise of inability to afford to treatment, or by the denial of coverage by insurance companies, some seem to see that as acceptable. It is not.

The costs of continuing our current system are simply unsustainable. Over the last decade, employer-sponsored health insurance premiums have increased 119 percent – four times the rate of inflation. A study of bankruptcy filings in 2007 found that 62 percent of them were related to medical expenses, and that it was not just the uninsured who were affected. In 80 percent of those bankruptcies, the filers had insurance that failed to adequately cover their costs. Without national health care reform, by 2018, national health care expenditures are expected to reach $4.4 trillion – more than double 2007 spending.

What Reform Must Do

Fundamental reform must meet the following basic criteria:

- Access to insurance for all Americans, regardless of income;

- Cost containment through increased competition and improved efficiencies;

- Preservation and strengthening of Medicare and Medicaid as a foundation for expanded coverage;

- Shared responsibility: Government, individuals, the industry, taxpayers and businesses must all equitably participate in reform; there need to be targeted incentives and penalties to encourage full participation by employers and individuals;

- Ensure reform is sustainable during all economic conditions: The federal government must create a system of counter-cyclical funding so that states have the necessary financial resources to ensure health care for al even during economic downturns. States like New York, which are ahead of other states in providing public health options, need to maintain our existing federal matches and must not be penalized for having been in front of the curve.

Obstacles to Change

The plans proposed by the House and the Senate all attempt to balance these goals with greater or lesser degrees of success. I believe the reluctance of some in the Senate to support a public option undermines the ability to achieve the appropriate balance of these goals because it leaves private insurers with little incentive to change their long-standing practices and huge profit margins, which have led to the skyrocketing costs we now see. A robust public option will provide more choice for consumers and businesses and create greater competition in the insurance market.

The arguments against a public option are also often blatantly self-contradictory -- arguing that we can't let government into the insurance business because government is inefficient, at the same time suggesting government would drive private insurers out of business by offering better benefits at a lower cost. And these critics seem to forget that government has run Medicare and Medicaid with much enrollee satisfaction for years.

The health care industry is a huge part of our economy, directly employing the equivalent of more than 357,780 full-time workers in New York, including 72,000 registered nurses. Nationally healthcare makes up more than 17 percent of our gross domestic product.

Reforming health care is not an easy thing, and we have certainly seen past presidents who took on this issue fail. But this time around there seems to be a greater recognition that we must address this crisis now, both for the well being of our citizens and for the economic health of the country. We can and should fight over the details of the final plan, and hopefully do so in a civil and constructive manner, but in the end we must recognize that the worst possible outcome is the status quo -- a broken health care system, with out-of-control costs, which leaves millions of Americans unprotected.

Liz Krueger, a Democrat, is the New York state senator from District 26 on Manhattan's East Side.

A Floor Not a Ceiling for Health Reform

All eyes are now on Washington’s health care reform efforts. But since the 1980s, health care reform in this country has largely been generated at the state level. There is a critical danger that the health care legislation being developed in Washington will legally block state initiatives. The power of interest groups limits what we can realistically expect from Congress, so it is important that the legislation protect and promote the ability of states to do more.

Here’s some of what states have done -- with New York in the forefront. Programs for prenatal care for low-income pregnant women began at the state level in the early 1980s and later led to national legislation to provide federal support. Senior citizen prescription drug programs were created in many states long before Medicare Part D was enacted, and many would agree that the state programs are better designed. The Child Health Insurance Program, or CHIP, began with state programs in a few states and then was supported by federal matching funds. The recent change to let CHIP cover children in more moderate-income families was a response to state efforts to expand the highly successful program. Several states expanded publicly-funded health coverage for low- and moderate-income adults.

State governments have led the way in protecting consumers in the private insurance market. Laws limiting restrictions on pre-existing conditions, rules protecting consumers and health care providers from being unfairly denied payment for medically necessary services, and other reforms have come from our state capitols, not Washington.

In some states, giant multinational drug companies have been reined in by state legislation restricting marketing and pricing abuses.

Letting States Do More

Each state is different. Some will want to do more than Washington does, and some won't. This is America, after all. The federal legislation should be a floor, not a ceiling.

"Pre-emption" is the legal term for one level of government taking over a field of law and barring other levels of government from acting in that area. Sometimes federal law explicitly pre-empts state or local laws. Even when there is no specific pre-emption language, the courts often rule that a federal law has pre-empted the field.

Major corporate interest groups often push for language in federal legislation to pre-empt state or local government action. They don't want state laws to give consumers more protection than a federal law provides. On the other hand, federal law can also specifically allow state or local governments to enact additional legislation.

In this instance, health insurance companies and big employers will argue that allowing state initiatives will make it impossible for them to operate across the country. That doesn’t hold water. Multi-state companies have always worked with different state laws on insurance or consumer protection, different labor markets, and even different zoning or environmental laws. Anyone smart enough to run a multi-state company can handle that complexity.

We should be more concerned about families who will need help from their state government in dealing with gaps in coverage and consumer protection that will likely be left when Congress is done.

Some lobbyists say they want to "let" people buy health insurance from out-of-state companies. But insurance companies can already sell policies to people in other states -- as long as they obey the state’s insurance laws. What the lobbyists want is a clause in the federal legislation to make it easy for out-of-state insurance companies to sell without complying with state laws.

I hope Congress will enact strong legislation to give all of us access to quality affordable health care. But no matter how optimistic one might be, let's also be realistic. With special interest lobbyists sitting at the health care reform table in Washington, at the end of the day there will be a lot of room for improvement. Families and health care providers will need somewhere to turn.

If Congress pre-empts state health reform initiatives, it will shut down the engine that has done the most in recent decades to help Americans get the health care they need.

No matter what Washington does, we will continue to need the new ideas and improvements that can come from the 50 states – whether it is expanding access to affordable coverage or protecting consumers and health care providers. Congress must guarantee that state reform efforts can go forward.

Richard N. Gottfried is the state assembly member from the 75th district on Manhattan's West Side and chairs the Assembly's Committee on Health.

An Option the Public Needs

We can no longer view public health care as an option, it is a necessity. While Congress is bogged down in political lobbying, New Yorkers confront the "choice" between their pension or health care coverage, rent or medication. Millions of New Yorkers face these choices today, with over 1.3 million New Yorkers uninsured and even more underinsured. We must take this opportunity to allow those who have no other options a chance to live a healthy and productive life and receive the type of medical care we all deserve.

According to the New York Urban League's State of Black New York, diabetes in New York City has doubled in the past eight years, and it is estimated that one third of these people do not know they have diabetes. In this city, black New Yorkers have a higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease, strokes, heart attacks and hypertension than the general population, and nearly 15,000 New Yorkers die every year from cancer according to the city health department. With all these diseases, the long-term prognosis greatly improves if they are detected early through prescreening and preventative care.

The public option, now being proposed, calls for a government insurance plan as well as private insurance. While the exact proposals vary, some kind of public option would create more choice for the public, spur increased competition in the market and allow those who are shut out of the current system to enter. Access to government-issued health care will provide competition for private health providers, lower costs and help to close the healthcare gap between lower-income and more affluent Americans.

The model already exists for the federal government to provide a cost-effective and efficient option. The best public option would be run similar to Medicare. Currently, the administrative costs of government run Medicare are lower than that of any other large health care plan. Like the current Medicare, the best public option would protect the rights of all to essential health care functions and pool the risk between the healthy and sick, thereby lowering cost.

The public option can be a cost effective, efficient form of health care. It is not simply for those who are uninsured -- we can all benefit from these necessary reforms. By opening the health care market to more options, those uninsured, underinsured or with no other choices will have the freedom to choose.

A healthier America is more productive, costs less and results in an overall higher standard of living. By injecting the market with this new option, all health care options, private and public, would be forced to become more inclusive and less expensive. Low-income families, people of color, and those most in need of health care have been shut out for far too long. It is time for change to truly come to America.

Arva Rice is president and CEO of the New York Urban League.

New York: Model or Warning?

What does health care reform mean for New York?

The better question might be what New York’s strict insurance regulations and high spending on Medicaid means for the nation. If Congress follows in our footsteps -- as key bills in the House and Senate seem to do -- New York's situation might not get any worse, but certainly won’t get any better.

And the status quo is simply unsustainable in the long run.

New York’s world class hospitals and physicians offer cutting edge health care -- at least if you have good health insurance. Currently, there are about 2 million uninsured in the state, about 14 percent of the non-elderly population (residents over 65 are covered by the federal Medicare program).

Regulating and Spending

But Albany has not ignored the problem of the uninsured. New York’s private, individual health insurance market is among the most heavily regulated in the nation. New York state laws mandates "guaranteed issue" of private health insurance, meaning that insurers cannot deny coverage because of health status, such as pre-existing conditions. The law also mandates community rating, which requires insurance companies to charge policyholders the same premium, regardless of age, gender or health.

These policies were intended to make insurance more affordable for New Yorkers who are older or who have chronic health conditions. Instead, prices have shot up, as young, healthy people were charged higher premiums and decided they were better off without expensive coverage they would probably never use.

In fact, the market for individual, unsubsidized health insurance has nearly disappeared, plummeting by 96 percent since 1994, after the reforms were implemented. New York City residents can expect to pay at least $9,036 a year for individual coverage, or $26,460 for family coverage -- hardly the "affordable" premiums reformers expected.

As the private market atrophied, Albany responded by expanding coverage through public programs like Medicaid. But New York’s Medicaid spending (projected to be over $49 billion in 2010) is breaking the state budget. We spend far more on Medicaid than any other state in the nation, in part because the program has become heavily politicized in Albany by powerful union lobbyists. Gov. George Pataki, for instance, cost tax-payers billions when he cut a backroom deal giving raises to workers in the powerful Service Employees health care union in return for their support for his 2002 re-election bid.

To their credit, Gov. Eliot Spitzer and then Gov. David Paterson recognized that Medicaid spending was out of control and the state wasn’t getting above average health outcomes for our much higher levels of spending. But fixes to date have been largely cosmetic -- in fact, Albany has used federal stimulus funds to expand Medicaid coverage. Paterson projects that nearly one out of every four New Yorkers may be on the Medicaid rolls by 2013.

In New York's Footsteps

The reform plans being considered in Washington, D.C. closely follow New York’s flawed strategy, including guaranteed issue and community rating requirements, increasing Medicaid coverage (to cover people with incomes of up to 150 percent of the federal poverty level) and billions in new taxes on health insurance companies along with heavy subsidies to help the uninsured buy government-mandated coverage. The only twist is a requirement that the uninsured must buy coverage, and employers must offer coverage or pay a penalty, moves that advocates hope will help keep young and healthy residents in insurance pools and so lower costs.

The problem is that this approach has already been tried in Massachusetts, which added an individual mandate in 2006. Since then, state spending has skyrocketed, and the Bay State has the most expensive insurance premiums in the country -- projecting double-digit increases again next year.

If Congress continues on its current trajectory, we’ll see more of the same: higher insurance costs, higher health care costs, more taxes and more deficit spending. That’s bad news for New York, which is already grappling with a severe fiscal crisis.

Looking at the Alternatives

If we’re going to get control of our health care costs, lower the number of uninsured and reform safety-net programs like Medicaid, we need to get beyond the screaming matches and finger-pointing that characterizes so much of the health care debate.

Here’s how:

-- Let markets do what markets can do well: set prices and allocate resources. In a recent report from the Manhattan Institute’s Empire Center for New York State Policy, researchers Stephen Parente and Tarren Bragdon advocate for a handful of market-based reforms that could make private health insurance much more affordable.

They found that repealing the community rating and guaranteed issue laws would reduce the number of uninsured by 18 percent and 19 percent respectively, and lower premiums by 42 percent. Letting New Yorkers buy health insurance plans licensed in Connecticut and Pennsylvania, where policies can cost 25 percent less than in New York, could allow as many as 26 percent of the uninsured to buy their own policies. Overall, these market reforms would lead up to 780,000 New Yorkers back into the private market.

-- Set up a safety net for New Yorkers with high-cost, chronic illness. Parente and Bragdon advocate creation of a pool for high-risk New Yorkers who would otherwise have to pay high premiums. Today, 35 states have such pools.

-- Tell Congress to focus on real, bipartisan reforms that gradually bend the cost curve of health care. The president promised not to sign any health-care bills that cost more than $900 billion or increased the deficit by one dime. The current bills meet that pledge -- but only through fiscal gimmicks, such as assuming that Medicare will slash physician reimbursements by more than 20 percent starting in just two years. That will never happen, pushing the House and Senate versions of reform well north of $1 trillion. New Yorkers will pay for those costs through higher taxes, lower wages, and higher insurance premiums.

A better approach is to start with basic, fundamental reforms -- like fixing the tax treatment of health insurance. Economists generally agree that excluding employer-provided health insurance from income taxes is unfair (the rich get more of a benefit than the poor), arbitrary (why link insurance to employment?) and expensive (by making health insurance seem free, workers ask for generous plans that drive up health-care spending).

Replacing that exclusion with a universal tax credit or standardized tax deduction for all Americans would help millions of the uninsured afford coverage, put money back in people’s pockets through higher wages, and slow the growth in health care costs that is crippling private and public budgets.

The basic idea has been embraced by everyone from Sen. John McCain to one of Obama’s health care advisors, Jason Furman. By mixing a safety net for those with chronic illness to market incentives that put patients and families in control of their own portable health insurance, we can help slow the rise in health-care costs and cover the uninsured.

We have tried time and again to fix health care by relying on top-down solutions cobbled out behind closed doors in Albany and D.C. They have failed every time. We need a different approach.

Mr. President, do you still have that reset button?

Paul Howard is the director of the Center for Medical Progress at the Manhattan Institute and managing editor of MedicalProgressToday.com.

New York and the Health Care Debate

Photo (cc) Jess J

With the House having approved an overhaul of the nation's healthcare system Saturday, the action now moves to the Senate. The Obama administration and other observers agree the health care bill faces a tough battle there, and whatever emerges could be different in significant ways from what the House passed over the weekend. By most accounts, the United States, the only developed nation without national health insurance, is now closer to adopting health care reform than at any time since President Theodore Roosevelt endorsed the idea in 1912.

Such a sweeping change will undoubtedly touch almost all Americans. New Yorkers have a number of particular concerns. Health care is not simply a service here, it is a major industry. New York currently provides more health services to its residents -- more health coverage, better public hospitals, tighter regulation of the insurance industry -- than many other states. And health care here is expensive.

As politicians bat proposals back and forth, New York officials have worried that the health care bill could penalize states like New York that already offer relatively generous benefits under Medicaid -- the government program providing health coverage for low-income people. And hospital officials in high-cost areas, such as New York and Los Angeles, have expressed concern that they could be hurt by efforts to focus on "value" and low expenses.

As the debate heads down to the wire, we asked several New Yorkers with expertise in health policy to discuss what the health care changes might mean for New York -- and what kind of legislation would most benefit New Yorkers.

Fixing a Broken System: State Sen. Liz Krueger writes that New York and the rest of the country can't afford to let this moment pass without addressing our health care crisis.

New York -- Model or Warning?: Paul Howard, director of the Center for Medical Progress at the Manhattan Institute, warns New York's effort to provide health insurance to all of its residents should offer a cautionary tale for Congress as it crafts a health care bill.

A Floor Not a Ceiling: Richard N. Gottfried, chair of the State Assembly's health committee, urges Congress to enact a bill that will allow states to fill gaps in the national law and provide health programs that meet the needs of their citizens.

Challenge in the Senate: State Sen. Thomas Duane says the version of health care reform proposed by the Senate Finance Committee would punish states like New York that have taken the lead in health care.

An Option the Public Needs: Arva Rice, president of the New York Urban League, argues that a government insurance plan -- the public option -- is essential to help those who have been shut out of our health system for far too long.

Taking the Temperature on City Health Policies

Photo (cc) _MaO_

Public health policy under the Bloomberg administration is understood popularly as "you're going to live healthier, whether you like it or not."

Michael Bloomberg heralds a number of achievements in his eight years in office -- forcing chain restaurants to post calorie counts and instituting bans on indoor smoking and the sale of food containing trans fats. These things stand along side more positive measures, such as Bloomberg's move to grant 1,000 permits in 2008 to "green carts," mobile food vendors offering fresh fruits and vegetables.

In Bloomberg's eyes, all his efforts certainly have paid off. When the two-term mayor received the Julius Richmond Award from the Harvard School of Public Health in October 2007, he hailed his administration's accomplishments: "The result is that New Yorkers are living longer than ever and, for the first time since World War II, living longer than the average American -- and that gap has grown every year since 2001."

Bloomberg's health legacy spreads beyond the bitter smoker standing outside a bar in the rain or the Coney Island visitor thinking twice about ordering the 1,000-plus calorie cheese fries at Nathan's to a range of policies affecting New Yorkers' lives.

The Thomas Frieden Show

When it came to the Department of Heath and Mental Hygiene, like many agencies, Bloomberg chose the individual he believed was the best person to run the agency. No one could argue with Thomas Frieden's credentials to be health commissioner. He left the department this year to head the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Not everyone approved of the job he did, however. The dissenters include HIV-AIDS activist groups such as Housing Works. It has accused Frieden of being secretive and uninterested in community input in policymaking, as well as focusing too much on data tracking and health monitoring and not enough on direct care.

Judith Arroyo, who as president of Local 436 of District Council 37 represents city health workers including public health nurses, said that the latter complaint reflects a general change in the field of public health over the last two decades. She said that Frieden, like many in the profession, was moving away from direct care and into tracking trends so he could shape future response methods.

"He reorganized and prioritized his money differently," she said. "A lot of it went into education and tracking, the electronic health record. That's going to help a lot."

Not many municipal labor leaders speak so highly of their former management counterpart as Arroyo does of Frieden.

"As far as I was concerned he was an excellent health commissioner," she said, noting that Frieden instituted measures to hold community health groups and city programs more accountable for their performance. "You needed a commissioner to take the department of health in hand and shake it up and send it on the road to the new public health issues that are out there."

She added, "Before then we had all sorts of programs, [but] nobody was asking for results, saying, 'Is this really working?'"

The Kids Are Not Alright

One shortfall of the administration, according to several health advocates, has been health-care for children.

During his first campaign, Bloomberg promised to centralize school-based health care under the health department rather than have it under the now-defunct and oft-maligned Board of Education. He didn't keep the pledge, Arroyo said, and instead power sharing between the health and education departments has created bureaucratic confusion in school health care.

"When you got two people in charge you got no one in charge," she said. The result, according to Arroyo, is inefficient delivery of health-care in the schools.

Funding for school healthcare has been cut due to the city's budget shortfalls. While members of Arroyo's union have not suffered layoffs, some clerical staff supporting school nurses have lost their jobs. This, Arroyo said, has made it more difficult to keep track of children's health.

"Now the nurse is in the school by him or herself trying to do everything," she said. "And when you leave someone there without assistance, especially without clerical assistance, then the nurse has to prioritize and the result is the paperwork, the statistical data goes on the bottom of the list because the nurse is going to help the child first. Then [the city is] not getting the data that they need to make decisions about schools and resources. … The program is not going to data entry itself."

The city also shut several school dental clinics this year, despite protests.

"Nothing that anybody said could convince the health commissioner not to do that," said Judy Wessler, executive director of the Commission on the Public's Health System, a two-decade old health-care advocacy group.

At the time of the closing, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene said in a statement, "We would very much prefer not to have to make this service reduction. However, lacking other options, the agency decided to eliminate a service that is available from many other sources."

Access: Getting There

Photo (cc) Vidiot

When Bloomberg was first elected the Emergency Medical Service already had been a part of the Fire Department for several years (it was previously under the auspices of the Health and Hospitals Corp.).

Union leaders representing emergency medical workers often have complained that their members are "second-class citizens" next to the firefighters, so often lionized in the public eye. But it's more than just living in the shadow of the "Bravest." The emergency medical workers have a lower pay scale that leads to high attrition rates. Skilled responders either seek promotion to firefighter or find work elsewhere rather than move up to the Emergency Medical Services officer corps because the money isn't enticing enough.

Moreover, in the last round of budget negotiations, the City Council came up with funding to stop Bloomberg's plan to eliminate 16 fire companies but did not spare the cut of 30 ambulance tours. Patrick Bahnken, who as president of DC 37 Local 2507 represents FDNY Emergency Medical Technicians and Paramedics, said this will result in a slower response to medical emergencies. In addition, he said, it will cost the city revenue because the private ambulances that will take care of the tours may take patients who might otherwise have gone to a public facility to a private hospital.

Fire Department officials have noted that, despite the cuts, the number of ambulance tours has increased since the Fire Department and Emergency Medical Services merged. Response times continue to fall from year to year, one spokesman repeated, but union officials argue morale is falling as well.

With two hospitals recently closing in Queens, along with the emergency medical cuts, Wessler foresees problems.

"There's clearly a backing-up of emergency rooms and that's been very clearly shown," she said. "There very possibly is also an extended time for ambulances."

Access: Getting Care

For Wessler, Bloomberg has done a better job overseeing the Health and Hospitals Corp. than his predecessor, Rudolph Giuliani.

He has "shown a lot more care for HHC and the public hospitals," she said. "That's been really important."

However, Wessler expressed concern that the city has not done more to provide direct care outside of the public hospital.

"Access to care issues other than in HHC have not been a strong point in this administration," Wessler said.

But referring to Frieden's successor, Thomas Farley, she said, "Could that change under a new health commissioner? We're now in discussion with him."

Ari Paul is a reporter for The Chief-Leader, a weekly newspaper covering the New York City civil service. He is also a correspondent for Free Speech Radio News, and a columnist for the on-line publication, The Faster Times.

Mentally Ill Seek More Independence

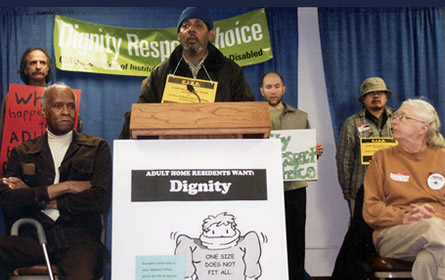

photo by Gail Robinson

It's the simple things in life that bring Irene Kaplan a sense of joy -- things most people take for granted. Deciding when she goes to bed, how to decorate her apartment, when to take her medicine. She likes buying her own groceries, choosing what she eats and how she cooks it; lately she has been experimenting with Caribbean spices and wants to bake more bread.

"What people like about it is the smell of bread baking. It's absolutely drool worthy. I've been experimenting with multigrain bread and Italian style. I've been using different healthy oils. It's a whole new, wide open world once you get out of the home," she explained.

A bout of pneumonia and a telegram letting her know that she no longer had a job led to Kaplan's stint as a homeless person and her eventual arrival at an adult home, a for-profit facility where the state places mentally ill adults. Kaplan spent 16 years in such a home.

Earlier this month Federal District Court Judge Nicholas Garaufis ruled that keeping mentally ill people in these homes violated their rights by preventing them from functioning as part of society. The state is still deciding whether to appeal a decision that could have a dramatic impact on how New York cares for people with mental health problems.

Kaplan, though, has already left her home. Thanks to state funding for supported housing for 60 patients, she lives in her own small apartment in Brownsville. She gets therapy and assistance from local groups as she works to reconstruct her life.

Now as a result of Garaufis' ruling, more patients like Kaplan may have a similar chance at freedom. Whether that happens, though, depends on how the state responds.

Not So Welcome Home

Since the state phased out its mental institutions in the 1970s, it has grappled with how to deal with mentally ill adults. For-profit homes, such as the one where Kaplan lived, have become the standard treatment centers for mental patients in New York. Over 4,000 New Yorkers with mental issues are housed in adult homes throughout the city.

In 2002, the New York Times ran a series about adult homes and the problems that ran rampant in them at the time. Reporter Clifford Levy found abuse and neglect of patients and that homes subjected residents to unnecessary medical procedures to take advantage of Medicare. In a 2003 article the Times referred to adult homes as "little more than psychiatric flophouses."

Following the Times series in 2002, advocates and the Pataki administration moved to reform the adult homes. The administration proposed spending $8 million to send social workers and caregivers to adult homes to increase the quality of care and evaluate whether some patients would be better served in other settings. But after strong lobbying by owners of adult homes, the legislature took $6 million of that money and allocated it to a program to give cash bonuses to adult homes that fared well good inspections -- essentially, advocates say, bribing them to provide a decent standard of care.

A taskforce was put together by the Pataki administration to address the care of the mentally ill. It recommended that the state move thousands of mentally ill adult home residents to apartments or small homes in communities. This was all supposed to be accomplished by March of this year. In the end only 60 patients were moved including Kaplan.

Over the past several years, some of the abuses have been addressed with better monitoring from the state. Adult homes are licensed and regulated by the New York State Department of Health. The State Office of Mental Health licenses and regulates mental health providers that diagnose and treat patients in the adult homes. Homes are regularly inspected.

Patients and advocates say there are good homes and bad ones, but as a whole they say adult homes effectively cut off patients from the outside world while fostering a sense of dependency and helplessness. In effect, these new institutions, they say, have become prisons that warehouse patients without any eye to letting them return to society.

Going to Court

In 2003, lawyers representing thousands of adult home patients and advocacy groups filed a suit in U.S. District Court in Brooklyn alleging that the state had violated the Americans with Disabilities Act by segregating the mentally ill.

The lawsuit said that most patients would be better off in their own apartments where they could receive treatment. This, the suit said, would also save the state money. It asked the court to block the state from sending the mentally ill to adult homes.

In his decision, Garaufis ruled in the complainants' favor by agreeing that the state violated the rights of the mentally ill in New York City. But he stopped short of barring the state from sending patients to adult homes. Still, Garaufis indicated in the decision that the state should consider providing apartments or small homes to patients who are not a threat to themselves or others.

Garaufis ordered the state to submit a "remedial plan" by October. The plaintiffs, including disability advocates, will be allowed to critique the plan.

The ruling only applies to homes in New York City, but the state will likely have to overhaul the entire system by which it services the mentally ill. Advocates expect the decision to have national ramifications since many other states also rely on adult homes to care for the mentally ill?.

The Next Move

So far the Paterson administration has remained mum on its plans. Jill Daniels, spokeswoman for the state Office of Mental Health, said that the judge's 210-page decision is still under review. "It's a long decision. Multiple agencies are involved," she said. Paterson's office did not return calls for comment.

A number of advocates are calling on the Paterson administration not to appeal the decision. Glenn Liebman, chief executive officer of the Mental Health Association of New York State, said New York should instead do now what it could have done to avoid the suit in the first place. "The state should have moved years ago to change conditions in adult homes. The state should have done a better job. They did some good things but they did not take a comprehensive approach," he said.

Saying he is "pleased with the decision," Sen. Tom Duane, who serves on the Senate Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Committee, said he thinks "the Paterson administration is very sympathetic" to the ideas expressed in the ruling. Duane said he plans to work with the administration to develop more supported housing for the mentally ill.

Lisa Newcomb, director of the Empire State Association of Assisted Living, which represents some homes, criticized the decision for casting the entire adult home industry in a negative light. She said the decision seems to assume that many of the patients in the homes are capable of functioning at a higher level than they actually can. According to Newcomb, sizable number of patients probably need the care and supervision the homes can provide.

Newcomb added, though, that she recognizes that more options for independent living are needed. "Honestly, we need more of everything," she said.

Paying for the Alternative

The real struggle facing the state is likely to be financial. Advocates acknowledge that the state is confronting fiscal crisis and that finding affordable housing in New York City is no easy task. But they say that providing the mentally ill with an apartment and finding them therapy and other services in their areas will actually be less expensive than paying to support their stay in large adult homes. And advocates say that a support structure of case workers and healthcare workers will be readily available to the patients.

Garaufis agreed. In his decision, he wrote that it costs at least $7,946 a year less per patient for the state to provide "supported housing" to the mentally ill than to pay for a stay in an adult home, which costs around $47,946 a year. Garaufis also found that supporting a patient in an adult home costs Medicaid twice as much as it does to keep a patient in supported housing.

Advocates insist there are a number of funding options, federal and otherwise, that could initiate a supported housing program across the state. They say the program could be ramped up over the next few years.

The other financial consideration comes from the adult home industry, which is not exactly keen on giving up a steady source of income. Advocates say adult homes are represented by a "very powerful lobby," that has been able to get its way with the legislature in the past.

Rediscovering Independence

Adult home residents speak out at a press conference in 2005

In his decision Garaufis pointed to the stigma of living in an adult home and said it can curtail social and professional options. The rules and restrictions, such as limits on visitors and not being able to have a phone, run counter to the image of an independent functioning person. Garaufis also noted that, while homes tend to focus on training in life skills, such as cooking and shopping, residents rarely have the chance to apply their skills in society.

Advocates acknowledge that not all patients will be ready to live on their own, but they say they should have the choice. Kaplan, who as a member of the Coalition of Institutionalized Aged and Disabled has been very active in advocating the rights of the mentally ill, agrees.

She admits that some patients need more help than others, but believes more harm than good is being done by keeping them all in one place and segregating them from society.

At Surf Manor Homes in Coney Island Kaplan was told what and when to eat and when to bathe. She had limited contact with the outside world and recalls being scolded for changing her linens, being coerced and intimidated into following instructions, and having to pick her roommate off the floor at night. She particularly remembers suffering summers without air conditioning.

Kaplan said she knew she was simply "too functional" to be in an adult home. "I did a lot of things for myself: I clean my room, take care of my personal hygiene needs. I didn't need that kind of support," she said.

While Kaplan recognizes that not everyone is as functional or independent as she is, she said living in a home erodes a person's self reliance. She says it is hard for some, after years of regimentation, to fight for more freedom or even to want it. "They do your shopping, do your cooking, help you shower. It is not conducive to a sense of independence," she said

Ready for the Next Move

Derek White, though, wants to move on. Three or four years ago he was living on the streets and addicted to drugs when he found himself in a hospital in White Plains. From there White was sent by health officials to Palisade Gardens, an adult home in Westchester where he received the support he needed to rebuild his life without drugs. White became involved with the Coalition for Institutionalized Aged and Disabled -- he is the president of the chapter in Palisade Gardens -- and works as an inspector for the local Board of Elections.

White credits the home for getting him back into the swing of things. "This place is not bad. ... I know for a fact that a lot of homes are a lot lesser," he explains.

But still White is ready to move on. He is tired of going to dinner only to find ground beef replaced by ground turkey, and ribs and pork chops pulled off the menu because of budget cuts. "I think I'm ready to go now," he said without any sense of anger or frustration. "I miss doing things for myself. I miss cooking, I miss choosing what I get to eat."

White imagines himself in a one-bedroom apartment, perhaps a studio, anything to get him back into society and making his own choices. He still wants some of the counseling and support he gets from the state. For now at least, no appropriate option is available.

"I've got nothing bad to say about this place. They helped me," White said. But now if I could get a little bit of help to get out of here. ... I'm ready to move on."

At this point the hopes of White and hundreds of other patients rest in the hands of the state.

Health Care, Development Dominate Debate in Forest Hills

With its pleasant residential neighborhoods and fairly affluent population, District 29 in Queens avoids many of the ills facing the city's grittier areas. But like so many Americans, residents of this area have major concerns about health care.

The closing of hospitals and the delivery of medical services to the district's residents has been a key issue in the campaign for the City Council seat currently held by Melinda Katz, who decided not to see re-election and is running for city comptroller. Like people in other parts of Queens, residents of the area also are concerned about development.

The race features six Democrats: Heidi Chain, a lawyer with the city Department of Finance who received the 2008 New York Police Department Woman of the Year award; Albert Cohen, an immigrant from Tajikistan, who has his own law practice; Michael Cohen, who represented Forest Hills in the State Assembly from 1999 to 2005; Melquiades Gagarin, media manager for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund; Karen Koslowitz, a former City Council member; and Lynn Schulman, the chair of Community Board 6.

The winner of the Sept. 15 primary will run against the Republican candidate, Bartholomew F. Bruno, in the Nov. 3 election.

A Hospital Shortage?

In a span of 12 months, three hospitals in Queens have closed. One, Parkway Hospital, the city's only privately run hospital, was in District 29. (The other two were Mary Immaculate Hospital and St. Johns Queens). In the wake of the closure, residents of Kew Gardens and surrounding neighborhoods worry about a shortage of hospital beds and long waits at emergency rooms.

Heidi Chain

The volume of patients at Forest Hills Hospital has increased by 40 percent from a year ago, and the number of patients who are being admitted is up about 12 percent, according to public relations spokesman for Forest Hills Hospital Terry Lynam.

"They [hospitals] have people practically in bunk beds," said Barbara Stuchinski, a local resident.

Chain expressed dismay that the hospitals ever were allowed to close. "They bail out banks, we bail out General Motors, and we didn't bail out the hospitals to protect the folks in Queens," she said, her tone reflecting her disbelief. To help fill the gap, she would establish a service helpline to provide immediate round-the-clock help.

Melquiades Gagarin

The closing has had very real effects, according to Schulman, who works at Woodhull Medical Center in Brooklyn. "The number of ambulance tours in the districts have gone down so response time has gone up," she said. She hopes to open an ambulatory care center in the district to provide immediate assistance to residents.

In Michael Cohen's view, the closed hospitals must be replaced. "Either reopen those hospitals or open new facilities," he said. "On a temporary basis, we should expand a walk-in clinic, but that is no substitute for a hospital." Money for this could come from a stock transfer tax or a bond issue approved by voters.

Albert Cohen would try to reduce the burden on the hospitals by promoting preventive care. To accomplish this, he would invest in medical screenings to identify health concerns before they send an individual to the emergency room.

Rezoning the District

The recently approved rezoning of Forest Hill's Austin Street won applause from the candidates. Austin Street has become the trendy shopping destination for residents with big name stores such as Sephora and Barnes & Noble. The rezoning is intended to promote more residential development in the already crowded area.

Karen Koslowitz

Koslowitz, who has very distinct red hair, has been credited with shutting down strip club Runway 69 when she last served as council member. That helped create the current boom in development on Austin Street.

While Michael Cohen supports the overall rezoning, he has concerns about parking. "I am critical in the plan with the amount of mandatory parking that would be provided," he said.

Albert Cohen has also focused on parking problems in the district, holding a press conference to complain about angled parking spaces on 108th Street and the ticketing of driver who don't back into their spot.

On another development question, five of the candidates have endorsed the rezoning to limit sizes of building in the Cord Meyer area, but in a debate, Albert Cohen opposed the change. He said the new limits are aimed at the Bukharian community, many of whom have built large homes in that neighborhood. According to TimesLedger newspaper, the rezoning " has highlighted the tension between the Bukharians and non-Bukharians."

Gagarin would change zoning rules to allow for the creation of more schools.

As the area has boomed, rents have increased. Many resident worry about the expense and fear they might have to another neighborhood. Schulman, vowed to advocate for legislation that would let the City Council set rent guidelines, as opposed to having the state legislature do it.

In the Home Stretch

The campaign has been largely free of acrimony, as the candidate compete for money and support in advance of primary day.

Albert Cohen

Chain, who has the support of many police groups, leads in fund-raising, but there's a bit of a twist. Unlike her opponents -- and the vast majority of city candidates apart from Mayor Michael Bloomberg -- she is not participating in the public finance system, reportedly because she does not think candidates should take taxpayer money in these tight economic times. She has raised almost $207,000 in private donations -- with more than $125,000 of that coming from herself.

Now it turns out Chain may not have saved the city any money afterall. City Hall has reportedthat Chain's fundraising and not particpating in public financing "triggered a provision of the Campaign Finance Board program that gives opponents an additional $95,000 in public funds. That equals $7,000 more than she would have received had she joined the program and received matching funds for raising the maximum amount from others."

Among the others, Koslowitz has raised the most private money -- $93,730, followed by Schulman with $87,260, Michael Cohen with almost $46,000 and Albert Cohen with about $43,000. Gagarin trails with $17,599.

Lynn Schulman

Schulman, who ran unsuccessfully for the seat eight years ago, has the backing of the Working Families Party and the Service Employees Union this time around. The

Times has endorsed her as well.

Koslowitz, who has the Independence Party nomination, is backed by City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, who has campaigned with her.

Chain has support from several police groups

This article was written under a partnership between Gotham Gazette and the Baruch College's Department of Journalism and Writing Professions.

Closed Hospital Plays Key Role in Jackson Heights Race

Any number of potential City Council candidates saw their plans thrown into turmoil in late 2008 when the City Council voted to extend term limits and allow incumbents, including Mayor Michael Bloomberg, to run for a third term in their respective New York City offices.

Helen Sears

The move whittled away a number of challengers in District 25, which encompasses Jackson Heights, Corona and East Elmhurst. But two -- Daniel Dromm and Stanley Kalathara -- have remained in the primary race to challenge incumbent Helen Sears. With a spirited primary race underway, the conventional wisdom -- that an incumbent always wins -- might not hold true here. The winner of the Democratic primary will face Republican Mujib Rahman in November.

The diverse district faces an array of problems, including a lack of health facilities, development and overcrowded schools. While the candidates all seek to address those issues, their platforms emphasize different areas. Sears, who was first elected in 2001, is taking on the district's health care dilemmas; Dromm, a schoolteacher and union leader who is also a gay activist, is focusing on education reform; Kalathara, a lawyer and businessman, wants to clean up the neighborhood by improving the quality of life and attract dollars that would otherwise be spent in Manhattan.

The Hospital Closing

The fault line of this campaign is the recent closing of St. John's Hospital. When Caritas Healthcare, the company that ran St. John's Hospital and Mary Immaculate Hospital, also in Queens, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy early in 2009, the hospitals were unable to keep their doors open. Even before Caritas' bankruptcy, St. Johns had been plagued by a shortage of beds and outdated equipment.

Consequently, the 100,000 patients serviced in their emergency rooms must now go to other medical centers. Residents of Corona, East Elmhurst and Jackson Heights have to use the already strained resources of the two remaining neighborhood hospitals, Holliswood and Queens Hospital Center.

Sears' opponents hold her responsible for the closure of St. John's. Sears maintains that she moved quickly to keep the health center open. New York State extended money to the hospital, but said it could not make regular contributions.

"She only showed up at a protest at the very end. She should have started [taking measures to avoid this] since her election," said Dromm.

Kalathara said, "I am not going to play the blame game." But he cited his concern about the impact of any re-emergence of swine flu this fall, noting that the two remaining hospitals serving the densely packed district were already seeing a doubling in cases

Planning for the Future

Sears, a former healthcare professional, has spent a great deal of time defending her past two terms in local debates, rather than speaking of her aspirations for a third term. During her two terms, she said, the Corner Care Pavillion opened as a health center for neighborhood residents. Now she said, it will add a woman's health clinic. "This district is incredibly diverse -- every country in the world is represented here," she said. "A woman's clinic will bridge cultural differences and will provide and teach women how to seek healthcare."

Daniel Dromm

Interviewed in a restaurant where the waitress speaks Spanish, Dromm cites his experience in advocacy and community affairs. "I recently organized a documentary screening about Muslim Sikhs to be shown in a Jewish center," he said.

His self-titled Dromm Plan vies to improve life for community residents with measures such as ending the self-certification practiced by real estate contractors and reducing noise pollution by pushing through legislation. He also proposes measures to help the area's many immigrants, such as addressing the employment scams which they too often face. "A center for day-laborers where they could meet potential employers would create safer situations and ensure union jobs by bringing immigrants into them," he said.

Kalathara, a self-made man who prides himself on his awareness of neighborhood difficulties, holds his interview in his neighborhood law office where the clientele are of Indian and Latino origin. He said he wants to address foreclosures, job loss and safety on Roosevelt Avenue and Junction Boulevard. "Installing lights, on stretches of blocks that often go without them is another plan to ease crime," he said.

He plans to push legislation to secure daily garbage pickup for his district and proposes the widespread use of charter schools to improve the education standards in city schools. "I will donate 10 percent of my salary to give funds to the most worthy community organization or school in this district," he said.

Stanley Kalathara

Kalathara extols his campaign as "a message of belief, opportunity." Holding himself up as an example of the American dream -- Kalathara worked his way up from an Indian immigrant-busboy to a lawyer -- he said, "I want to set an example for others." Indignant about the economic disparities between his district and many Manhattan neighborhoods, he said, "Queens is not a second class world. I want to make sure Queens citizens are treated first class,"

On the day of his interview, Kalathara was fighting to stay on the ballot. He sat, confident behind his desk in his Queens law office. "I've sent one of my lawyers to handle the case," he said. When questioned about the validity of the signatures on his ballot petitions, he said simply that Dromm, who had challenged them, "is a sour grape."

Votes for Immigrants

In this district of many immigrants, there is debate about Resolution 245, which would give non-citizens the right to vote in New York City elections. Dromm strongly supports the act, while Kalathara merely agreed. At a recent debate, Sears had no opinion to give, saying, "I'm here to tell you that I'm not sure where I'm on this. I haven't given it much consideration."

The passage of resolution 245 would have an enormous impact on the political landscape of New York City, particularly in this heavily immigrant Queens District. Estimates place those who are of age but cannot vote in New York City elections at 1.3 million, easily more than one-eighth of the city's overall population.

Explaining his support for the resolution, Dromm said, "There should be no taxation without representation. This is a basic American tenant, and it's the key to ones destiny."

The Anonymous Charges

On a far murkier level, controversy also has arisen over anonymous leaflets about Dromm that some have characterized as part of a "homophobic smear campaign." The leaflets reportedly allege that, as a 16-year-old, Dromm was arrested for prostitution. He has said he was simply kissing his boyfriend but that, in the 1970s, " being gay meant that you could be put away against your will in a mental institution."

Kalathra and Sears both condemned the attacks, although Sears has been criticized for not speaking out sooner and more forcefully against the advertisement.

Money and Support

Sears remains the campaign heavyweight in terms of budget. She leads with $128,493. Dromm is second in funds with $103,958 and Kalathara with $92,489.

Dromm has endorsements from the Working Families Party; Service Employees Union Local 1199, which represents healthcare workers; the United Federation of Teachers, as well as by local politicians including state Sen. Tom Duane and three City Council members from Queens.

An Outer Borough Drought

Photo (cc) tatoodjj

This story was done through a partnership between The Huffington Post's Eyes and Ears citizen journalism program and Gotham Gazette. Gotham Gazette reporter Courtney Gross wrote the piece using stories from New Yorkers gathered through The Huffington Post and Gotham Gazette. Sign up here to join Huffington Post's citizen journalism team covering New York to be part of more of these stories.

Fruit stands are Manhattan's new hot dog vendor, minus the mustard and ketchup.

Their street corner takeover has sparked some New Yorkers, like Upper East Sider Jamie Kayam, to carp that their neighborhood is oversaturated with apples, bananas and overly ripe white cherries.

"In NYC, buying fruits and vegetables has never been easier!" Kayam wrote in an e-mail to Gotham Gazette and The Huffington Post. "When recently discussing life in the city with some friends, a key complaint that came up was that there are too many fruit stands in Manhattan!"

Across the river, Kayam's plight might be a blessing.

The Upper East Side has one of the highest concentrations of food retailers in the city, according to the Department of City Planning. The neighborhood ranks third in the number of grocery stores per capita, boasting more than 22,000 square feet of strictly supermarket space per 10,000 residents, according to the department.

But out of Manhattan, greens get elusive. In the South Bronx, residents have about half of that supermarket space. In Brooklyn's Bedford Stuyvesant, 82 percent of retailers are unlikely to sell fresh fruits and vegetables, and in some areas of Upper Manhattan that number increases to 90 percent, according to city planning.

The Huffington Post and Gotham Gazette asked you how far you travel to get fresh fruits and vegetables. Many of you said veggies are ripe for the taking in your neighborhoods. But a majority of those of you who responded, almost two thirds, live in Manhattan, brownstone Brooklyn or other affluent areas of the five boroughs.

Those outside of these areas may not find a fruit flood, but a produce desert.

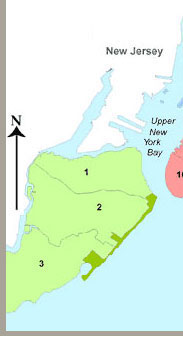

|

|

|

|

|

This map uses data from the city's Going to Market report released last year. Rollover a district to find out how many supermarkets there are and how that compares to the number of residents.

A Borough Away

Chelsea is an agricultural Atlantis, says resident Steve Panepinto.

"There's a wide selection of fresh fruit and vegetables on virtually every corner not to mention in the half dozen supermarkets that are within three to four blocks of my apartment," he told us. (Chelsea actually has the highest concentration of grocery stores in the city, according to city planning.)

About 100 blocks north it's another story.

"I live in the West Harlem area, and it is incredibly difficult to find quality fruits and vegetables," writes Erin Barker. "It's a big problem. Even when stores have this stuff, it's usually not in good shape -- bruised or not usable. I think it is more difficult in my neighborhood than it is in wealthier areas of Manhattan that have more upscale grocery stores."

Barker, according to the city, is on point. The lower the median income, the harder it is to find fresh fruits and vegetables. (Chelsea's median household income is more than $100,000, while West Harlem's is about $30,000.)

The discrepancy, according to Ben Thomases, the Bloomberg administration's food policy coordinator, explains why the city is targeting areas in Upper Manhattan, central Brooklyn and the Bronx to grow (pun intended) access to fruits and vegetables. It's pushing for produce on the shelves of corner bodegas, has issued 1,000 green cart permits for specific neighborhoods and is now working on financial and zoning incentives to get more supermarkets into certain areas.

"A lot of low-income communities in Upper Manhattan and the outer boroughs were decimated in the '70s and early '80s," said Thomases. "At that time, naturally, a lot of supermarkets left. When the communities were rebuilt, for a mixture of reasons, the supermarkets didn't really come back."

The administration has already kicked off its financial package, which includes tax abatements for new supermarkets and for those that want to renovate or expand. The city will provide a sales tax exemption for anything related to expanding or constructing a grocery store, from cash registers to two by fours. It also is offering a mortgage recording tax waiver.

To root even more supermarkets in needy neighborhoods, the city's Planning Commission proposes to allow developers to build bigger spaces if they include a supermarket in their plans. If a large mixed-use development has a supermarket on its bottom floor, the city will support the addition of the same amount of square feet of residential space, in effect adding thousands of square feet to the structure. City officials say they will also lower the amount of parking spaces required for supermarkets and are allowing larger grocery stores in manufacturing areas. Currently, these zoning proposals are under review and should be voted on by the City Council by the end of the summer.

Getting Fresh Foods

So far, the city is aiming low. A success to Barry Dinerstein, a senior planner at the city's Department of Planning, would be another 15 supermarkets sprinkled throughout the city's highest need areas in the next few years.

That goal is unlikely to alter Keri Roberts's two-mile bike ride from her Windsor Terrace apartment to the "local" Costco.

"My biggest complaint about living in New York is how hard it is to get fresh produce," Roberts, a technical writer and 16-year Brooklyn resident, said.

For many like Roberts, it's not just about proximity, but cost. If you're on a fixed income, the corner bodega's fruits, while close to home, come with an inflated price tag. "It's just so expensive," said Roberts.

So, some New Yorkers walk (a.k.a. wince and make like it's an added health bonus). Oliver Noble, who is on fixed income, travels 25 blocks from his Park Slope apartment to a vegetable market. Last week, he told us, those blocks cut his produce cost at least in half. He got green peppers for 69 cents a pound -- a bargain from the usual $1.99 a pound.

At least for the next few months, the city's green markets can be a summer savior. The Council on the Environment of New York City, a city-affiliated nonprofit, is running 49 greenmarkets this year across the five boroughs, bringing fresh vegetables (at least temporarily) a lot closer to home for scores of neighborhoods, said Sabine Hrechdakian, the council's special projects and publicity manager. Of those, 23 accept food stamps.

But only 18 of the markets are open year-round, seriously depleting the fresh food supply come the colder months.

Hence, the city's new pro-supermarket campaign.

"We recognize a farmer's market does not take an area that is really underserved by fresh produce and make it all better," said Thomases. "They generally operate one or two days a week. People need to shop seven days a week."

People like Michael Paone, a Crown Heights resident who heads to Park Slope's food cooperative for affordable veggies via bike or two subway transfers. Fresh Direct or a quick and accessible purchase at the local bodega is out of his price range, leaving him with little options.

"It's a shame to me that the main place I can afford (monetarily and biologically) to patronize is not in my neighborhood," Paone told us. "One day, soon, I hope this will not be so."