New York Needs a Green New Deal

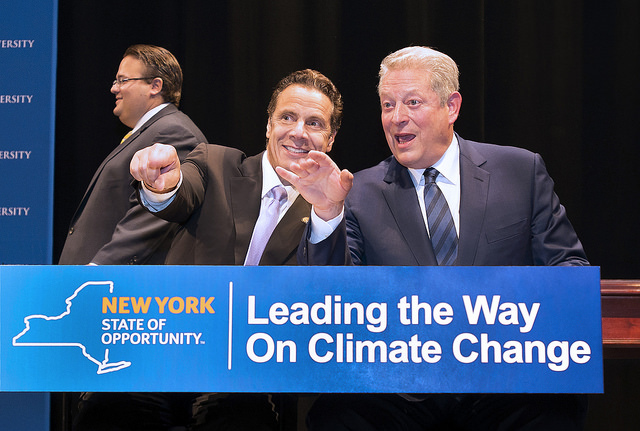

(photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Office of the Governor)

Think of it: a bold vision that simultaneously addresses the greatest existential threat facing humanity while providing thousands of good jobs across New York. Want an added bonus? There won’t be a need to increase taxes on ordinary New Yorkers.

A “Green New Deal” for New York could mean thousands of jobs and a pathway to 100% renewable energy, which will be necessary to stave off the worst effects of climate change, all paid for by charging a fee on corporate polluters that pump greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

We are coming off a record-breaking forest fire season on the West Coast while Hurricane Florence has ravaged the Carolinas, a year after Maria devastated Puerto Rico. And, at least in the short term, national leaders will keep their heads in the sand and continue to collect campaign donations from the fossil fuel industry. States have the opportunity to set the model for how to tackle climate change, and New York can and should be one of these states.

While Governor Cuomo has taken important steps to address climate change, including banning fracking in the state and creating the United States Climate Alliance (the coalition of states that committed to the Paris Accords following the country’s exit), New York actually lags behind other states. Only 5% of New York’s energy come from renewable sources -- compared with California’s 25% and Vermont’s 40% -- and there are multiple plans to build more fossil fuel infrastructure, guaranteeing a continued reliance on dirty energy.

To truly be a climate leader and make the state the progressive model he often says it is (and position himself for any aspirations beyond Albany), Cuomo needs to pass bold legislation that puts New York on a path to 100% renewable energy. After all, just last week, Governor Jerry Brown of California signed into law major legislation that will do just that. What’s more, with the victories of a progressive wave of state senators on primary day, September 13, state government may be ripe for bold climate legislation this session. And that legislation already exists.

Two bills with strong support among grassroots and labor organizations, the Climate and Community Protection Act (CCPA) and the Climate and Community Investment Act (CCIA), would put New York on a trajectory towards 100% renewable energy. The CCPA calls for a just and equitable transition to a clean energy economy, while the CCIA would force those most responsible for climate change to foot the bill by charging a fee on corporate polluters.

These bills would not only set a strong climate agenda, but would also launch a necessary jobs program at a time where there’s national concern over loss of jobs due to automation and outsourcing. By investing in renewable energy and energy efficiency, New York could create thousands of jobs that pay a living wage including retrofitting buildings, installing solar panels, and updating our energy infrastructure. We could also put people to work making our state more resilient, and fix crumbling infrastructure that is increasingly vulnerable due to superstorms and sea level rise. By charging a fee on oil, gas, and coal, this all will be paid for by the fossil fuel industry, without a need to raise taxes on New Yorkers.

A “Green New Deal in New York” could be the benchmark for other states and eventually the country to follow. It is no longer enough for politicians to claim that they “believe” in climate change. We need a real, comprehensive agenda to address this challenge head-on. In order to demonstrate climate leadership, Cuomo, assuming he wins reelection, should work with the Legislature to pass the CCPA and the CCIA as quickly as possible and set the example for the rest of the nation.

***

Ari R. Lieberman is an attorney and the legislative coordinator for 350Brooklyn, a grassroots climate change organization affiliated with 350.org. On Twitter @the_greenmarble.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

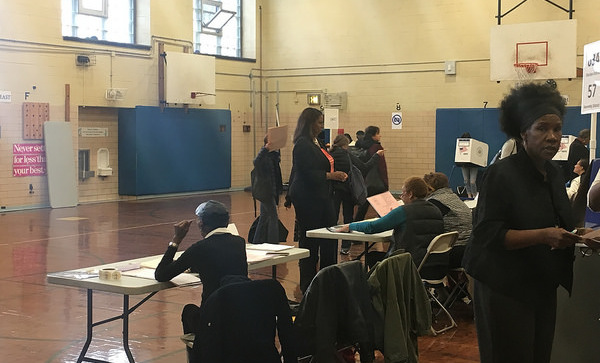

Surging Democratic Voter Turnout in New York City May Mean Greater Importance in State Elections

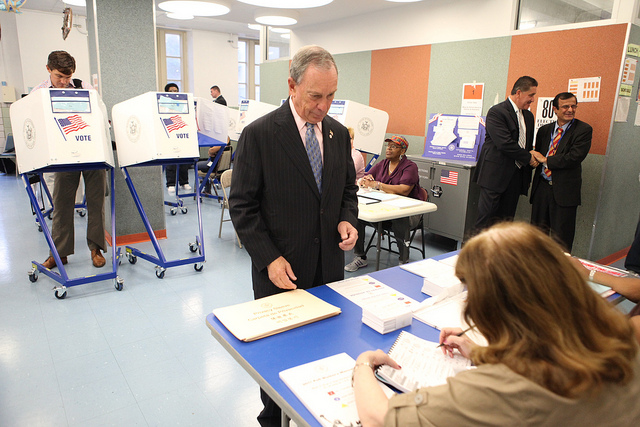

(photo: Mayor's Office/Kristen Artz)

There was an extraordinary turnout in New York City in the just-completed statewide Democratic primaries on Thursday, September 13. In the city alone, 855,000 Democrats came to the polls. That vote substantially exceeded the crowded and competitive 2013 Democratic mayoral primary (690,000), was nearly triple the city’s turnout in the 2014 Cuomo-Teachout primary (298,000), and came somewhat close to matching the Clinton-Sanders turnout in New York City of practically 1 million Democrats (996,000).

The good news about increasing voter participation may also foretell change in the dynamics of statewide elections. Democratic turnout in New York City was 57.3% of the statewide turnout of 1.49 million, a higher share than the geographic turnout model being used in two Siena Research Institute polls on the primary in July and September 2018, each of which assumed New York City’s share of statewide turnout would be 50%.

You might say ‘who cares about a bunch of polls?’, but polls are based on turnout from past elections, and those turnout models are also what candidates and campaigns use to allocate their time, energy, money, and resources. And, polls are frequently covered by the news media. If turnout in New York City is rising, campaigns must spend more money and time and volunteer effort there, and candidates’ positions must strongly appeal to residents of the nation’s largest city.

Turnout in the rest of the state also differed from the Siena Poll models. The final September poll modeled the turnout at 50% New York City, 13% suburbs, and 38% upstate. The actual results were 57% New York City, 18% suburbs, and 25% upstate. The number of Democrats outside New York City that came out to vote also rose substantially from 2014, more than doubling from 276,000 to 635,000, meaning there was far broader interest in the election this year across the entire state than in 2014. Cuomo won two-to-one in New York City, three-to-one in the suburbs, and 57-43% upstate.

While New York City had big increases in raw numbers and an increased share of the statewide primary vote, the real test of the city’s importance in statewide elections will now come in the general election. In the past three gubernatorial, off-presidential year elections -- 2006, 2010, and 2014 -- the city’s share of the statewide vote has been dismal.

Despite being 43% of the state’s population, the city’s share of the statewide vote in the past three general elections where the election for Governor was the top of the ticket has not reached 30%. In 2014, the city was 1 million of 3.8 million votes, a mere 26.5% of the vote. In 2010, when Governor Cuomo was first elected to the position, the city was 29% of 4.6 million votes. In 2006, when Eliot Spitzer won handily, the city was 28% of 4.4 million votes.

The question now becomes, was the surge in turnout in the city a one-off due to a few unique circumstances, or will it be sustainable because of a more engaged Democratic constituency in the age of Donald Trump?

[Read more: A Closer Look at Democratic Primary Turnout, Margins & Geography]

***

Jim Brennan was a member of the New York State Assembly for 32 years, where he chaired four committees. On Twitter @JimBrennanNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

To Save the MTA, Push ‘Fast Forward’ Ahead Quickly and Responsibly

(photo: MTA New York City Transit/Marc A. Hermann)

The fight to fix our ailing transit system took a significant step forward in May when New York City Transit President Andy Byford released his “Fast Forward” plan to dramatically accelerate comprehensive fixes to our city’s subways and buses. We, along with many other legislators and advocates, praised the plan and Byford’s work to create it. Fast Forward isn’t just a clear roadmap to a modern subway system; it’s also a very necessary roadmap to MTA reform.

Now it’s time for the MTA to take the next step toward transparency as the governor and Legislature begin the difficult work of finding sources for the billions of dollars necessary to pay for Fast Forward -- as well as the authority’s expected capital needs. While Byford estimates the cost of Fast Forward to be $40 billion, it is essential that the MTA provide a budget detailing the plan’s costs as well as its 20-Year Capital Needs Assessment. If state government is to do its job, we need to know what fixing our subways and buses will really cost. Without a detailed budget, the necessary revenue that must be provided to save our transit system will be unlikely to materialize and millions of riders will suffer the consequences every day.

The collapse of our subway and bus systems isn’t Byford’s fault. It is, in fact, ours. Decades of indifference, neglect, and underfunding from Albany has hamstrung our public transit and now threatens to irrevocably damage the fabric of our city. Make no mistake, without public transit; New York City ceases to be. So it is our duty to fix it.

Historically, Albany’s inaction has stemmed in part from the lack of a clear vision of how to fix public transit. Now that we have that framework in place, the final step still remains. The MTA must show us exactly how it plans to implement the plan and how much it will cost.

There have been many ideas for how to provide additional revenue to the MTA—congestion pricing, value capture, a millionaires’ tax, new corporate taxes—but not a single one of these proposals will ever gain enough support in the Legislature if lawmakers are in the dark as to the exact costs of the agency’s capital needs.

Time is of the essence. The governor will deliver the next State of the State on January 9 and the next preliminary budget a week later. The MTA cannot wait until then to submit to the Legislature its capital needs and a budget for the Fast Forward proposal. The costs of Fast Forward need to be factored into the governor’s executive budget long before its release, and the scope and importance of the Fast Forward plan requires that the Legislature is given ample time to review and hold hearings on the authority’s proposed costs well before budget negotiations begin in January.

Once the MTA shows us the numbers, then it becomes Albany’s task to make sure we raise the necessary revenues without unduly burdening already-frustrated straphangers. Unfortunately, Albany doesn’t have the best track record when it comes to securing real funds for the MTA. The authority’s current capital budget, the 2015-2019 Capital Program, was only approved in 2016—sixteen months late—and of the $32 billion that was approved, the source of most of the state’s $8.3 billion share has yet to be identified. This type of delay and the lack of a clear identified revenue source cannot happen if we expect the Fast Forward plan to be successful.

Beyond submitting its Fast Forward and 20-Year Capital Needs Assessment budgets this fall, the MTA should submit future Capital Program budgets earlier, in order to demonstrate the need for dedicated, long-term revenue streams, the Capital Program should have a longer timeline than its current five years.

This year Assemblymember Carroll drafted and passed in the Assembly a bill, A.11094, which would have required the MTA to submit its capital budgets earlier than currently mandated—but the bill never came to a vote in the Senate. To facilitate long-term planning, the MTA should share the full cost of the 15-year Fast Forward plan rather than breaking it up into the five-year chunks.

The current system of temporary fixes is unsustainable and cannot continue. Without a budget and time for the Legislature to review it, the state will again fail to act on a concrete plan to finally fix and modernize our subway system. There might be some serious sticker shock in Albany, but it’s time for us to roll up our sleeves and get the job done. If we don’t, then Fast Forward will remain Byford’s dream, while millions of riders suffer the daily nightmare that our subways have become.

***

New York State Assemblymember Robert Carroll represents the 44th Assembly District which is comprised of the neighborhoods of Park Slope, Windsor Terrace, Kensington, Victorian Flatbush and Boro Park. Nick Sifuentes is the executive director of Tri-State Transportation Campaign, a transportation advocacy organization. On Twitter @Bobby4Brooklyn & @Nick_Sifu of @Tri_State.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Real Story of Cuomo’s Dominant Primary Win

Gov. Cuomo, right, & Howard Glaser, the author, middle-left (Governor's Office)

Findley Lake, in Chautauqua County, on the western edge of the state, is about as far as you can drive from the Bronx and still be in New York State. It’s as close to Cleveland, Ohio as eastern Suffolk County is to the Grand Concourse. Chautauqua is a big county, land-wise, 1,100 square miles -- about 25 times larger than the Bronx. People in Chautauqua are spread out among rolling farmlands and lakes, about 132 residents in a square mile. The Bronx crams 34,000 souls into the same mile. Chautauqua is also about as white as you can get, 94 percent, while the Bronx is New York’s most-black county, with 430 out of every 1,000 residents.

You could argue that there are not two places in the state more separated by geography, racial makeup, culture, and politics. Yet, in last week’s Democratic primary, one thing joined, however briefly, midwestern Chautauqua and urban Bronx: they both delivered overwhelming electoral victory to Andrew Cuomo.

The Bronx went for Cuomo by over 80 percent, his highest margin in the state. Chautauqua delivered 64 percent for Cuomo, not quite the stratospheric number of the Bronx but an even higher percentage than Cuomo’s otherwise crushing margins in Brooklyn and Manhattan.

You could conjure up pretty much any other divide from this diverse state and the result would be the same. Nassau, the state’s richest county (median or family income), just about matched the poorest county (Bronx again) with 77 percent for Cuomo. Union households and non-union households were on the same track, according to Siena’s polling. And voters under 34 were actually more likely to vote Cuomo than voters aged 35-54, confounding conventional wisdom about where newly energized young voters would go (Cuomo won decisively across all age groups).

It’s no secret that Cuomo was backed by New York’s real estate community. But he was equally backed by tenants -- 80 percent of Bronx households are renters. He won those fed up with high taxes in Suffolk in almost equal numbers with tax and spend Upper West Side liberals. He won minimum wage workers in New York City and dominated among small business owners in the North Country, where small businesses represent over 90 percent of total businesses.

All of this in as high turnout a primary election as New York has ever seen.

So what to make of this absolutely dominant showing by Cuomo?

Much of the post-primary press narrative went like this: "Cynthia Nixon lost but progressives won because she moved Cuomo to the left. Cuomo’s margin was due to Nixon being a flawed candidate and Cuomo’s significant outspending over Nixon.”

Those are nice and simple memes, but they don't explain the results in any way. The near run of the table by Cuomo suggests this: New Yorkers weren’t buying what Nixon was selling.

If anything, New York as a whole demonstrated that New Yorkers like their progressivism, but they like it tempered with fiscal reality, with experience, and the desire and ability to find common ground between Findley Lake and Pelham Bay. That’s not what Nixon was selling -- but its Cuomo’s whole brand.

Nixon’s poor showing can’t be explained by being outspent. Money counts most in elections when it’s used to define a lesser-known candidate or a barely-known opponent. The Cuomo-Nixon matchup was the polar opposite. Every primary voter knew exactly who Cuomo was and knew exactly who Nixon was. And Nixon’s campaign wasn’t exactly cash-strapped. Even in New York, $2 million is real money. Had she spent three times more and Cuomo spent a third of his final tally, the result wouldn’t have been significantly different. New York primary voters are as sophisticated as anywhere on the planet. To suggest that only 7 percent of African-Americans supported Nixon because they were duped by ads is insulting or worse. She got her message out and New Yorkers, across the board, rejected it.

Nor was she the ineffective campaigner that she’s widely been made out to be. Her performance in the debate was more than credible. She’s a gifted communicator who produced strong ads. And while her depth on specifics was clearly limited, she expressed a grasp of the issues that wasn’t significantly different from that of the average politician. Campaigns expose a candidate’s flaws, and this campaign was no different in showing both Nixon’s and Cuomo’s vulnerabilities. She made mistakes but nothing disqualifying, holding her own, especially for a novice campaigner. And New Yorkers still said ‘fuhgeddaboudit.’

But perhaps the biggest myth of the primary is the “Cynthia Effect,” the proposition that Nixon pushed Cuomo left. She won by losing, goes the logic, because the specter of Nixon rallying activist Democrats forced Cuomo to adopt more progressive positions than he otherwise would have. The problems with this bit of conventional wisdom are manifold.

First, the polling on Cuomo’s standing with the Democratic left has consistently shown this is his strongest base of support since he ran for governor in 2010. He didn’t need to move left to gain progressive support, progressives have been his for almost a decade. As Siena pollster Steve Greenberg told me in analyzing the post election results, “Liberals like him, they have always liked him, and they continue to like him.” So it’s not surprising Cuomo outperformed Nixon even among the most progressive wing of the party. Siena’s pre-primary poll gave Cuomo a commanding 65-24 lead among those Democrats who self-described as liberal. Cuomo polled identically with moderates, and only somewhat lower with conservative Democrats. In other words, a Cynthia Effect with no effect.

The argument that Cuomo’s support for progressive issues suddenly sprang out of nowhere only after Nixon announced her run is belied by the facts. Marriage equality in 2011, the gun restrictive SAFE Act in 2013, banning fracking in 2014, $15 minimum wage and paid family leave in 2016 — progressive touchstones brought home by Cuomo, all years before a Nixon candidacy was a gleam in the eye of the Working Families Party.

The outcome should also put to rest the internecine divide in the Democratic Party over the question of whether the path to victory for Democrats can rely alone on registering, rallying, and turning out progressives. The theory on the left has been that if the party focuses on turning progressives out in force, it can win without diluting purity of message by trying to win over moderates or, heaven forbid, conservatives. Thus, say some Democrats in the post-Clinton era, there’s really no need to reach out beyond the base, just turn out the base and sweet victory will ensue.

The Cuomo-Nixon primary is the highest profile race to blow that nonsense aside. Turnout in the primary was sky-high, shocking political pros from both ends of the party. Nixon, the “pure” progressive, scored a paltry share of that enhanced turnout. According to the Democratic left orthodoxy, those new voters we saw waxing enthusiastically in Brooklyn coffeehouses should have been enough to hand her a nomination. They weren’t, it wasn’t -- and it won’t ever be. Not in a state this diverse in political and cultural make-up. (And while typically a spike in turnout amid an influx of newly registered voters signals trouble for an incumbent, in this race it appeared to have only further bolstered Cuomo’s margins, another sign of Cuomo’s unusually broad coalition.)

By defining Nixon’s loss as purely a function of Cuomo’s political muscle or Nixon’s inexperience, members of the media, progressive leaders, and others take the wrong lesson from the results. No candidate from the Sanders/Warren/Nixon wing of the party has been able to equally appeal to black voters in Brooklyn, Latinos in the Bronx, moderates in the suburbs, blue collar whites in Buffalo, and farmers in Chautauqua. Without that ability, would-be progressive leaders are talking to themselves. They narrow their appeal while Cuomo, carrying a results-oriented progressive standard cabined by fiscal restraint, reached Democrats across the board.

It’s a big state where diversity of interests doesn’t end at the New York City border. The message for progressives out of this election is not to double down on talking to each other (hello, Twitter) but to talk to, listen to, and persuade the non-converted.

New Yorkers made a conscious choice to embrace Cuomo’s realpolitik progressivism and reject Nixon’s ‘progressivism only for progressives.’ Most importantly, you can’t win in New York, or for that matter in the nation, by utterly failing to win over black voters -- Nixon likely got less than one in ten African-American votes, a shameful showing. She likely picked up less than a third of women’s votes. These numbers should force some soul searching by progressive leaders. “Nixon won by losing” is a useful piece of self-delusion in the wake of utter repudiation. But it’s a complete misread of the lessons of Cuomo’s victory for a successful progressive coalition on a statewide -- or national -- basis.

***

Howard Glaser has served in executive positions in the public and private sectors for 35 years. He served as Director of State Operations in Governor Andrew Cuomo’s first term, and spent this past year teaching urban policy at Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College. On Twitter @hglaser1.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

What I’ll Tell My Kids About 9/11

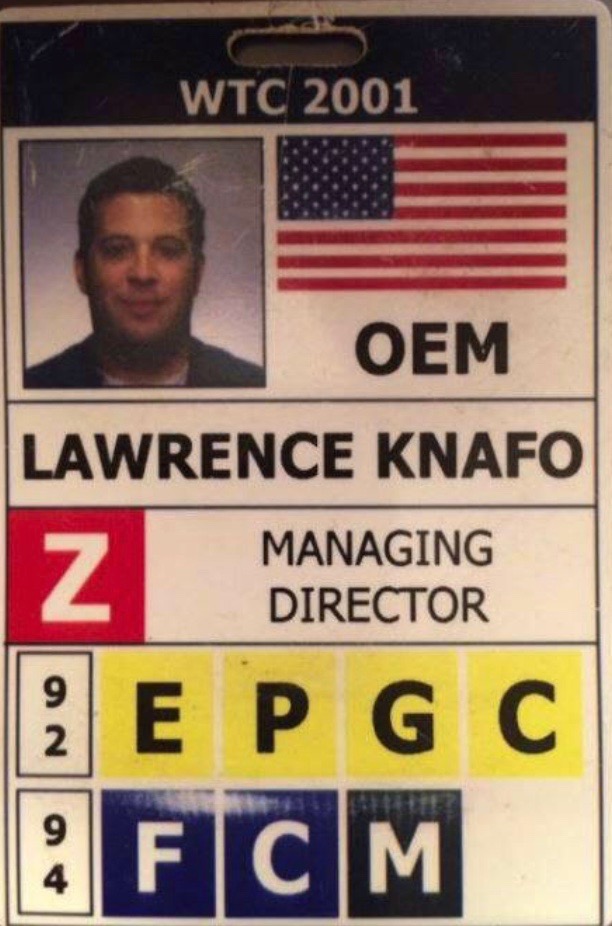

(photo: NYC OEM)

I recently saw the 9/11 inspired Broadway musical “Come From Away.” The show pays tribute to the 9,000 residents of Gander, Newfoundland – a group of ordinary people thrown into an extraordinary situation. Faced with thousands of stranded airline passengers, the people of Gander opened their homes and their hearts to strangers from all walks of life and all religions.

The show was a welcome reminder of the spirit shown by New Yorkers in the days and weeks following 9/11. It brought back memories of New Yorkers lining the streets to cheer on first responders and doing whatever they could to help one another during a surreal moment in our city’s history – a moment when our massive city felt a little more like small town Gander.

As the show brought 9/11 memories vividly back to life, I couldn’t help but note the reaction – or lack of reaction – of many around me. I assume that many in the audience were visiting New York from some faraway place, or perhaps were too young then to now remember that horrific day. While I tried to share in the joy of the musical and the positive story it told, I was struck at the lack of emotion many showed upon being reminded of the horrors of 9/11.

The next morning, I was taking my kids, 5 and 8, out for the day and reflected on the upcoming 9/11 anniversary. I’ve always told them how ground zero is a place that is very special to me but have only shared some of what really happened that day, and little of my personal story.

When my wife asked my son about 9/11, he shared what he knew, but when she pressed for more information, he simply said, “I don’t remember.”

At that moment, I was shaken. I could only wonder if I had failed as a parent. I wondered if I had failed as a New Yorker. And I wondered if I had failed those that made the ultimate sacrifice that day.

My wife insists that our kids are too young to know the details of what really happened, and perhaps she is right. Why ruin the innocence and joy of childhood with the reality of the evil that surrounds us?

But, I couldn’t help but wonder. Should I have told them about the horror that we all experienced that day? Should I have told them how the world changed? Should I have told them my story and how 9/11 forever changed me?

But, I couldn’t help but wonder. Should I have told them about the horror that we all experienced that day? Should I have told them how the world changed? Should I have told them my story and how 9/11 forever changed me?

How else could they learn the importance of remembering the lost. How else could they know to respect the police, the firefighters, and the EMS workers that keep us all safe.

How would they know that sometimes they should run towards danger to help others? And if not that, how else would they know that sometimes all you can do is try to help in whatever way you can – kind of like the people of Gander and all those New Yorkers who lined the streets to cheer on our first responders.

After 9/11, I used to wear a shirt with the logo “Gone, but not forgotten.” I remember every time I would put the shirt on, I would think: how could anyone ever forget.

But when I watched the reactions during “Come From Away,” I started to seriously question whether many had already forgotten - or worse yet, never known.

But it wasn’t until my son uttered those three words, “I don’t remember,” that I fully realized the meaning of “Gone, but not forgotten.”

Remembering 9/11 won’t just happen on its own. We all have a responsibility to share our stories and to teach those around us what happened when terrorists turned airplanes into weapons.

And as I thought about how we could better remember 9/11, I realized that’s exactly what the writers of “Come From Away” had done. They had told the story of 9/11 and in doing so, had helped to preserve our history. They made sure that we remembered those we lost and they helped honor those that did whatever they could to help.

“Come From Away” was also a good reminder that people from nearby as well as those far away suffered during 9/11. It was a reminder that many, many people have their own stories about 9/11. And it was a reminder that we must always tell the fully story of 9/11 – offering different perspectives, sharing the good, and, of course, sharing the bad.

Telling the story of 9/11 forces us to acknowledge the unthinkable things done to innocent people. But it gives us the opportunity to honor the heroes that raced into danger to save innocent lives – many becoming victims themselves. And yes, it allows us to share the stories of how we came together as New Yorkers and how we came together in Gander – wherever your Gander may be.

“Come From Away” helped me realize that there are many ways to tell a story. And with that, perhaps there are many ways to teach our children – to teach my children.

The irony of passing judgment on the “Come From Away” audience is not lost on me – I was quick to judge, but realize that just because the audience enjoyed the show, doesn’t mean they didn’t appreciate the significance of the story.

As a parent, I want to shield my children from life’s unpleasant realities, but I also want to make sure that their values are driven by our history...by my history.

I still don’t know how or when I’ll share the full details of 9/11 with my kids. My wife is probably right (she usually is) when she says they are too young to learn it all.

But while they may not be old enough to learn about terrorism, they are certainly old enough to learn what “Come From Away” reminded me – how love can, and did, conquer evil – in Gander and in New York City.

I’m going to start by teaching them that lesson.

***

Larry Knafo served in the FDNY, was a founding member of the NYC Office of Emergency Management (OEM) and served as the First Deputy Commissioner at the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications. After 9/11 he led development of the City’s Family Assistance Center, drove technology recovery efforts, and aided in the development of the City’s Emergency Operations Center.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

How ‘Independent’ Must the New York Attorney General Be?

The state Democratic convention (photo: Gotham Gazette)

One thing is for sure about the four candidates in the Democratic primary for Attorney General: each wants to be thought of as “independent.” Witness these self-descriptions:

Leecia Eve: “An independent advocate for all New Yorkers”

Tish James: “I’ve been independent all my life”

Sean Patrick Maloney: “I think I bring true independence”

Zephyr Teachout: “An independent fighter for New York”

This independent streak all intensified when James, endorsed by Governor Andrew Cuomo, prevailed for the party designation at the Democratic state convention. To diminish her resultant electoral advantage, the other three candidates sought to portray her during the primary campaign that followed as dependent upon Cuomo politically and therefore less likely to attack the pervasive corruption in state government, corruption that has reached into the governor’s own office.

It seems logical enough. Unlike most other state department heads in New York, the state attorney general is elected by the voters, not appointed by the governor (thus the claim to be “the people’s lawyer”). Lots of statewide elected offices were eliminated or converted to appointed through constitutional change over the last century and a half. Meanwhile, the attorney general remained elected. There must be some rationale, people reasoned, for persisting in this way over all those constitutional conventions. Assuring the office’s independence seemed an explanation that fit the bill.

But independence for what?

New York’s constitution is almost entirely silent on the attorney general’s job. Its powers are rooted in common law and further specified in statute. Chief prosecutor is not among them. There are some exceptions, but since the early 19th century criminal prosecution has almost always been the work of locally elected district attorneys. Read the candidates’ own campaign literature. Mostly they are not promising to prosecute corruption in Albany using powers the office has now; they are promising to seek constitutional and legal changes that would give them the powers to do this.

Then there’s the attorney general bread and butter: representing the executive branch of state government in court and advising state agencies on legal matters. Attorneys general who aspire to be governor (all of them, lately) may use their independence to decline to represent the state when they differ from the governor on policy, as was the case at times for Robert Abrams during the administrations of Governors Hugh Carey and Mario Cuomo. This caused the first Governor Cuomo to exclaim: “No candy store can be run this way. You have this massive operation called an attorney general but you can never tell when he will be willing to represent you.”

Interestingly, Eliot Spitzer as attorney general did just the opposite. At some political risk, he felt obligated to represent the state in court in defense of its then-ban on same-sex marriage even though he opposed this ban as a matter of state policy. But the point is this: “independence” may be a convenient excuse for the attorney general to decide not to do his or her job for personal or political reasons. Yet the state still must be represented; if the attorney general steps away, other lawyers must be hired to do the work.

Most New York attorneys general returned to relative obscurity after their time in office. Of the 56 who’ve served, two of the three with recognizable names (at least to the political cognoscenti) prior to the current era were attorneys general before the office was elective: Aaron Burr, later vice-president, and Martin Van Buren, later president. The third was Jacob Javits, the longtime U.S. Senator.

The office became a stepping stone to the governorship only lately, after Spitzer rediscovered the attorney general’s extensive powers under the Martin Act, passed in 1921 to counter rampant securities fraud. Because New York is an international financial capital, the state’s AG is uniquely situated to be a major player in policing the national economy. Here’s one place where independence does count. Spitzer’s aggressive pursuit of abuses by big Wall Street brokerage houses and investment banks under the Martin Act, followed by Andrew Cuomo’s and Eric Schneiderman’s after him, made the New York attorney general a nationally important figure.

Because Donald Trump is a New Yorker, the state’s attorney general is also uniquely situated among his or her peers to hold Trump accountable for his pre-presidential personal and professional financial practices. One result is the current lawsuit seeking the dissolution of the Trump Foundation for persistent illegal practices over at least a decade.

A strength of the American federal system is that it always provides a base of power in some states for the party out of power in Washington, D.C. Those who designed this system could not have imagined the complexity of our current intergovernmental federal arrangements, nor the degree to which public policy is now decided in the courts. Modern federalism has been further transformed through the use of these courts by state attorneys general to advance policy agendas.

Here again independence is key. State attorneys general of the party out of power in Washington have again and again joined in collaborative class action suites to challenge national policy and its implementation. Republicans sought to undo Obamacare, and are still at it. Democrats, with the New York attorney general in the lead, continue to litigate to block Trump administration actions on such issues as immigration and environmental regulation.

So as we New Yorkers choose an attorney general this year, we must be mindful that we are choosing a national leader to fight for New Yorkers on the key questions that face the state and the nation.

And also that we are picking a likely future candidate for governor.

As we do this we are already sure to make history, if only because every major candidate, including the Republican, Keith Wofford, is in a class protected by law against discrimination -- female, African-American, gay – from which we have not yet elected a person to hold either of these statewide offices of governor and attorney general. (Governor David Paterson, who is African-American, was not elected, but gained office by succession from the office of Lieutenant Governor after Spitzer’s resignation.)

But we need something more. We need an attorney general who makes history not just by who he or she is, but through doing the job -- with passion, energy, and the right balance of collaboration with and independence from the governor.

Don’t forget to vote.

***

Gerald Benjamin is director of The Benjamin Center at SUNY New Paltz.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

A Path to Reduce Building Energy While Preserving Affordable Housing

photo via the Urban Green Council

When it comes to combating climate change, the stakes have never been higher. The Trump administration’s failure to address this crisis means progressive urban leaders must do much more to reduce carbon emissions – especially in large apartment buildings that contribute so heavily to climate change.

One of the greatest challenges to addressing carbon emissions in residential buildings is ensuring that crucial energy efficiency upgrades don’t trigger rent hikes for low- and middle-income tenants living in rent-stabilized apartments. Rent-stabilized units account for a significant percent of large multifamily building space, so it is important to find a way to address this situation.

The good news is that we and dozens of other organizations have joined forces on a new proposal that would tackle this challenge – among others – by reducing carbon emissions at 50,000 New York City buildings while providing a plan to avoid hitting rent-stabilized tenants with the bill.

The new Blueprint for Efficiency by the Urban Green Council’s 80x50 Buildings Partnership – of which we and other organizations in the Climate Works for All Coalition are members – lays out a roadmap for cutting large building energy use by 2050.

As the Blueprint notes, city and state law currently allow the cost of many “major capital improvements” (MCIs) – including some efficiency measures like boiler replacements – to be passed on to tenants in rent-stabilized apartments. These costs then become permanent rent increases. They can also push units toward deregulation: above a set rent threshold, the units are forced out of stabilization. For too many tenants, MCIs mean higher rents they can’t afford, or even losing an apartment for tenants who are already stretched to the limit, rather than benefiting from lower energy bills and a healthier, better-maintained home. Additionally, taking apartments out of rent stabilization reduces the affordability of our housing overall.

So as part of this proposal, we are recommending new rules promoting low-cost, energy-saving measures for the rent-stabilized sector that do not qualify as MCIs, and oversight to ensure that if measures cause rental increases, action is taken to change the rules. We also believe there should be support and incentives provided so that the rent-stabilized sector can achieve the same kind of efficiency gains as market-rate buildings.

This kind of approach allows us to achieve significant energy reduction goals across the board, while protecting rent-stabilized tenants at every turn.

Beyond the rent-stabilized market, affordable housing owners and nonprofits often face thin margins and financing challenges, so efficiency upgrades are rarely a priority. The Blueprint recommends helping them through greatly expanded support programs, incentives, improved access to financing, and coordination with state-level programs that help reduce energy use.

Working with stakeholders who don’t often find themselves in the same room together we came up with these recommendations based on robust discussion and consensus-building.

Alongside all the Buildings Partnership members, we look forward to working as quickly as possible with the City Council and the de Blasio administration to translate our broader proposal into new legislation that can be advanced this year.

This would be a real win-win for all New Yorkers who care about combating climate change and preserving affordable housing across our city.

***

Maritza Silva-Farrell is Executive Director of ALIGN: The Alliance for a Greater New York & Stephan Edel is Director of New York Working Families. On Twitter @MaritzaSf and @GreenJobsNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New Approach to Low-Level Offenses is Working

(photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

How should police respond when someone is drinking a beer in the street, dropping litter, or engaging in other minor offenses? Up until a year ago, a criminal summons was the only answer, and if the person didn’t show up in court, he or she could be arrested on a warrant.

As a result, New Yorkers had as much contact with the system for low-level offenses as for serious crimes.

Consider that in the first half of 2017, there were 112,000 criminal summonses compared to 98,000 misdemeanor arrests and 50,000 felony arrests. The summonses practice had a snowballing effect on the justice system: over its history of this practice, many people failed to take a day off of work or find the time to settle the criminal summons.

More than a million warrants accumulated.

Last year, that all changed.

In city legislation called the Criminal Justice Reform Act (CJRA)—passed by the City Council under then-Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito and signed by Mayor Bill de Blasio—police now have the option to issue a civil summons instead of a criminal summons, which can be handled like a ticket in the city’s administrative law court, the Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings, known as OATH.

Under the CJRA, if the summons is filed at OATH for the hearing, the punishment is a fine. If a court date is missed, it does not result in a warrant and arrest like it could in criminal court.

And if found in violation after a hearing, the option is available to pay the fine or do community service. Community service at OATH is instructive and aimed at preventing future offenses instead of solely requiring the performance of menial tasks.

The effect of the law has been dramatic.

Since June 2017, criminal summonses and warrants for CJRA-eligible offenses are down 89 and 94 percent, respectively. Over the same period, serious crime fell 13 percent.

Warrants issued for failure to appear in court for a small set of low-level offenses—for example, drinking in public, entering a park after dark, unreasonable noise, and public urination—could reach as high as 5,000 in a single month. Now they are around a few hundred.

During this time, the Mayor's Office and the City Council also worked with the NYPD, district attorneys, the courts and other partners to clear more than 644,000 warrants for minor, non-violent offenses that were 10 years old or older.

There are, of course, exceptions to the new enforcement option for low-level offenses. Someone may still be directed to criminal court if he or she has two or more felony arrests in the past two years, has three or more unanswered OATH summonses in the past eight years, is on probation or parole, or if there is another legitimate law enforcement reason.

The success of CJRA is not just that police now have more options. Nor is it just that there is more proportionality in how we enforce the laws, though that is important. It is also that more people are attending to their summonses.

In May of 2017 appearance rates on criminal summonses were at 64 percent. In April of 2018 that number had risen to 71 percent—which is also a credit to the multiple partners, courts, police, district attorneys, and others who helped develop a redesigned summons form, to make directions more clear, and sending text message reminders that alert people of their upcoming court dates.

Enhanced appearance rates are not happenstance. One thing we know well, both from research and from everyday experience, is that people are more likely to obey the law when they believe that they are treated fairly and that the system is responding appropriately. When the punishment for low-level offenses is out of step with the seriousness of the offense, New Yorkers lose confidence in the fairness of the system as a whole and are less likely to comply.

It is one reason why the NYPD had already been issuing fewer criminal summonses even before the CJRA, considering new approaches to low-level offenses, and has expanded neighborhood policing, which emphasizes building partnerships with the community.

We do not know for sure whether this is the dynamic that is changing behavior but we have asked the Misdemeanor Justice Project at John Jay College of Criminal Justice to do an evaluation of the effects of the CJRA and hope to learn more in the year ahead.

We know this will not fix everything. Racial disparity still persists and we have work to do. However, this dramatically lightens the volume and weight of the system’s touches on New Yorkers who commit low-level offenses.

We are hopeful that this approach that relies on residents to live cooperatively with their neighbors while ensuring compliance through proportionate measures will create a virtuous cycle in which rules are followed because they are fair and just.

***

Elizabeth Glazer is the Director of the New York City Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice. On Twitter @CrimJusticeNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Reimagining the Brooklyn Democratic Party

(photo: Gotham Gazette)

The New York Times recently published a story about the Queens Democratic Party and how it stacked its Democratic County Committee with at least 21 people who had no idea that they were running for the position. One of the “candidates” actually lived in Florida. The Times article said, in part: “it is not entirely clear why the party would want to populate the committee with people who did not know they were on it.” In Brooklyn, it is totally clear.

For background, the Kings County Democratic Committee has a general membership of approximately 3,000 people. Every two years, in the September primary, each Assembly District elects both a male and female District Leader (officially called a “Member of the State Democratic Committee”). Collectively, the District Leaders make up the executive committee of the Brooklyn Democratic Party.

Like Queens, the general membership of the Brooklyn Democratic Party is filled with people who are unaware they are party officials or who have no interest in serving the Party. The leadership of the Brooklyn Democratic Party exploits this ambivalence by holding County Committee meetings in hard to reach locations, inaccessible by public transportation, and then telling members that they can skip the meeting if they give the County Chair their proxy votes.

By collecting proxies from uninterested or unaware members, the Party leadership gets the votes they need to maintain full control over the direction and agenda of the Party. It gives the Party leadership the numbers it needs to beat back any reform efforts and to deny grassroots Democrats a voice in the selection of the Democratic nominees for State Supreme Court or to fill a legislative vacancy.

The specific problems that exist in Queens have somewhat receded in Brooklyn. To his credit, when Frank Seddio took over as Chair of the Kings County Democratic Party, he agreed to adopt incremental reforms being pushed by the Brooklyn Reform Coalition. Many of these reforms are the ones that Queens reformers are still fighting for today. While there has been some improvement, Brooklyn still has a long way to go.

In the short term, the Brooklyn Democratic Party must end proxy abuse. No person, whether the County Chair, a District Leader, or a general member, should be allowed to hold more proxies than the number of County Committee members serving in their Assembly district.

Likewise, the Party currently will only pay for the County Chair to send a proxy solicitation to all members of the County Committee. District Leaders have no budget and lack the financial resources to individually send a similar solicitation. This imbalance can be cured by allowing proxies to be submitted electronically or by the Party funding a mailing for each and every District Leader who wants to solicit proxies.

The long-term goal, however, is to end governance by proxy.

There are over 1 million Democrats in Brooklyn. Certainly we can find a few thousand who are committed to building a vibrant, transparent, and inclusive Brooklyn Democratic Party. Every board or committee I have ever sat on had a rule against missing too many meetings. The same needs to be true with the Brooklyn Democratic Party. At the same time, to ensure a diverse and inclusive party, meetings need to be held at a variety of times and locations so that no one is excluded due to a serious obligation, such as working at night or childcare responsibilities.

All over the country, local Democratic Parties are vibrant, active, and impactful. They meet regularly, have subcommittees with important party-building responsibilities, and develop and promote a political platform. Brooklyn is the largest local Democratic Party in the country and does none of these things. Instead of being national leaders, we are lagging far behind. Implementing the reforms I’ve outlined here will allow us to grow into a national model of what a fighting Democratic Party can accomplish.

These are not revolutionary ideas. This is what local Democratic Parties do all over the country. Once Brooklyn’s rank-and-file Democrats demand these changes, these ideas will be impossible to stop and we will finally have the Democratic Party that Brooklyn wants and deserves.

***

Doug Schneider is a candidate for Member of the Democratic State Committee/District Leader in the 44th Assembly District in Brooklyn. On Twitter @DougSchneiderBK.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Labor’s Unsung Heroes

(photo: The Governor's Office on flickr)

A tribute to America’s workers, Labor Day has evolved beyond a day of parades and festivals duly celebrating the achievements of workers to one emphasizing the economic realities and civic significance of the unsung heroes responsible for the prosperity of our country.

Of these everyday heroes, no one is more unsung than the women of color and immigrant women who, in the main, bear the responsibility for raising their families while at the same time working outside the home.

All groups of women earn less than white males across communities and job categories, but the discrepancies vary greatly by race and ethnicity. White women earn 84 cents for every dollar earned by white men, Asian women earn 63 cents, black women earn 55 cents, and Latina women earn 46 cents. To put it in perspective, given the current pay gap, black women must work about an additional 200 days to make what white men earn in a year.

Here in New York, women of color and immigrant women form the bedrock of the labor force. They are frequently both the main or sole caregivers and main or sole wage earners in their households. They supply the bulk of the paid caregiving services, on which so many other New York households depend and account for a major share of the retail and restaurant sector workforce that drives our economy.

Yet the progress of women of color and immigrant women has not historically been a top priority for anyone, even philanthropies. Less than 7% of foundation funding goes directly to supporting programs for women and girls.

Today, there are determined, grassroots organizations forging strong approaches to expanding the economic security and well-being of women. The Business Center for New Americans and the Damayan Migrant Workers Association provide shining examples.

The Business Center for New Americans promotes the American dream of financial independence and home ownership, providing refugees, immigrants, women, and other New Yorkers with the information, counsel, and support needed to thrive financially. They advance entrepreneurship through microlending, combined with training and technical assistance, and homeownership through down payment assistance, training, and access to incentives.

The Damayan Migrant Workers Association empowers low-wage workers to fight for their rights by building leadership at the grassroots level to eliminate labor trafficking, fight labor fraud and wage theft, and to demand fair labor standards to achieve economic and social justice.

The New York Women’s Foundation is proud to support and salute these organizations, and our other grantee partners in this space, for their efforts to secure a better future for the thousands of women of color and immigrant women in our workforce. They, and those they assist, are our heroes on Labor Day and every day.

****

Camille Emeagwali is vice president of programs at The New York Women’s Foundation.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.