Democrats Must Act on Immigration Reform While They Still Can

A naturalization ceremony (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

The midterm elections are now behind us and the lame-duck session is the perfect time to tackle a long-standing problem: immigration policy. The issue has a profound bearing on most Americans' communities and schools, as well as their economic interests and notions of justice.

Specifically, Democrats must finally codify the rights of Dreamers, those who are beneficiaries of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, and remedy continuing worker shortages in key industries like agriculture, health care, construction, and manufacturing, where non-citizen labor is ready, willing, and able.

Democrats – who control the House and Senate until January – have a tight window to make this right. And they have bipartisan support among Americans. They should seize the opportunity, effective immediately. 2025 may be too late.

DACA status Americans – the overwhelming majority of whom are young Latinos and Latinas – are foreign-born individuals who came to this country as minors. They are Americans and must enjoy the same rights as all citizens. They have grown up in our communities and places of worship, and in our schools, sports leagues, and civic organizations. They shouldn’t be expected to return to countries that are foreign to them and where their safety is at risk.

In recognition of the hazards posed by repatriating these young people to their countries of origin – most of them nations riddled by authoritarianism, violence, and crime, then-President Barack Obama issued an executive order, enabling DACA youth to remain in the U.S. temporarily to study and work, while legislative efforts could be advanced to provide them permanent resident status and a pathway to citizenship.

In recent years, however, the Trump White House resisted the efforts of DACA status young people to be permanently incorporated into our national life and economy, opposing their permanent residence and a fair process that would allow them to become citizens. Courts, where immigrant-unfriendly judicial appointments have increased, have also stymied efforts to protect DACA status for millions of young people.

Yet 74% of Americans, when polled by the Pew Center, overwhelmingly support making DACA rights permanent.

Further research and evidence finds that 'DACAmented' Americans are remarkably productive and law-abiding – as K-12 and college students, workers and entrepreneurs, and volunteers across the nation – wherever they reside, study or work. Some of these young men and women have also served admirably in the U.S. military.

Congress should resuscitate and pass HR-6. The Act would establish a clear pathway to permanent resident status for DACA beneficiaries, including the right to reside, study, and work in the U.S. It would also prohibit states from denying otherwise eligible DACA youth in-state tuition and benefits at public colleges and universities. California, New York, and five other states now offer tuition assistance for DACA recipients, but all students with DACA status deserve the same tuition benefits as their peers across the nation.

Such action is essential to develop a nationwide pipeline of strong workforce talent that is better aligned with our changing demographics and increasingly global economy.

For similar reasons, effective immediately, Congress should pass legislation to more fully mobilize available noncitizen workers; doing so can help to address persistent labor shortages in critical fields like home health care and child care, and aid various supply chain sectors beset by the recent covid crisis (from agriculture to retail, construction, and technology).

Expanding economic opportunity and agency for the nation’s young, fast-growing, and heavily immigrant Latino workforce is a worthy investment in our nation’s future. Latino students and workers, many of whom are Dreamers and non-citizens, are essential contributors to our evolving multicultural society and economy. We need practical and reasoned policy interventions to activate their still-not-fully-tapped contributions.

The measures we propose here will not provide the comprehensive reforms that are needed to address our nation’s many immigration challenges, but they will establish a practical start that is worthy of bipartisan support in the waning days of the current Congress. The time to act is now.

***

Félix V. Matos Rodríguez is chancellor of City University of New York. Henry A. J. Ramos is senior fellow at The New School Institute on Race, Power and Political Economy.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Democrats Must Deliver for Asian-American Voters or Risk Losing More of Them

Co-author Grace Lee, center, with supporters (photo: @graceleefornyc)

As New York Democrats continue to assess our stunning midterm losses – including two state legislative seats in Southern Brooklyn with high concentrations of Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) voters – our party must reckon with the fact that we have failed AAPI communities when it comes to both outreach and policy.

As the fastest growing demographic in the country, Asian-American voters will only increasingly count in future elections. We are 17% of the city’s population, a number that will continue to rise. We hold the power to deliver the margin of victory in competitive races and more, yet we deserve to be treated as more than just a margin; we deserve to have our voices heard and our communities cared for.

As Asian Americans, we are deeply invested in the future of our Democratic Party – Grace is the Assemblymember-elect for the district that includes Chinatown and the only electoral district that Lee Zeldin carried in Manhattan, and Trip is one of just a few top political consultants who identify as Asian American. We are calling on Democrats to waste no time in wrestling with the consistent exodus of Asian-American voters from the Democratic Party that we have seen over the last decade.

In 2012, exit polls showed 73% of Asian-American voters supported President Obama. Compare this to the 2022 midterms, in which 40% of surveyed Asian Americans voted for Republicans. While a presidential electorate differs from those who vote in the midterms, a 15-point drop-off is a five-alarm fire that Democrats should respond to with both urgency and intention.

Here in New York, Lee Zeldin won plurality Asian-American districts in Brooklyn and Queens. His crime-focused message undoubtedly resonated with Asian Americans, while Democrats failed to adequately tailor public safety messaging to Asian-American neighborhoods whose residents live in constant fear of hate crimes. Our party also failed to educate Asian-American voters about how Zeldin himself helped fuel the hate that led to a nearly 400% spike in anti-Asian American violence; as a member of Congress, he repeatedly tweeted reminders that the coronavirus came from China, and he even voted against Rep. Grace Meng’s resolution condemning anti-Asian American hate.

Republicans are shameless at pursuing the votes of the very populations they have marginalized, whereas Democrats take the support of Asian-American voters, and all communities of color, for granted. The consequences are visible: just looking at a map, big blocks of red now cover chunks of Brooklyn and Queens, which could easily metastasize into other historically Democratic areas of New York.

So where do we go from here? We need a top-to-bottom, brutally-honest assessment of what went wrong, accountability for mistakes that were made, and a clear roadmap of what needs to change.

For starters, we need to take a hard look at the way we build Democratic power in Asian-American communities, and that begins by building trust in our political and public leaders. We need to prove that Democrats will keep their campaign promises and respond to the needs of their Asian-American constituents.

We must invest in holistic solutions to public safety and improve the economic vitality of our communities. We need to engage Asian Americans early, not just in campaigning but in actual policy-making. If Democrats want to earn the support of Asian-American voters, then we cannot steamroll an entire population when it comes to declaring sweeping changes to education and quality of life that affect communities – as the former de Blasio mayoral administration had done.

Asian-American voices deserve to be heard on issues impacting their communities, and adequate translation services should be in place to ensure that language is not a barrier to civic participation.

We also need to examine the financial investment (or lack thereof) in how campaigns communicate directly with voters. We need to do the work of expanding our relationships to include a new generation of community activists. We need to hire campaign staff from the community and people who can communicate with voters in the language in which they are most comfortable. We also need to build a bench by recruiting and investing in Asian-American candidates and supporting Asian-American government staff and consultants as they move up in their careers.

Our messaging, too, needs to be thoughtfully constructed to reflect the issues that Asian Americans care about, like public safety and education. We cannot use blanket Democratic talking points for every demographic, plastered on translated mailers sent two weeks before an election. But if we are doing policy right and delivering on the issues that matter to Asian-American voters, then the messaging should follow naturally.

Above all, Democrats today need to recognize that Asian Americans do vote and we do count; across much of the country, Democrats exceeded expectations, and Asian-American voters contributed to these strong election performances. But if Democrats fail to invest in the hard work of organizing Asian-American communities now, we will continue to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory.

***

Assemblymember-elect Grace Lee will be the first Korean-American woman to serve in the New York State Legislature, representing District 65 in Manhattan. She is a community organizer and mother of three young children. Trip Yang is the founder and president of Trip Yang Strategies, a political strategy and paid media consulting firm. He was named by City & State as one of New York’s Top Political Consultants in 2022. On Twitter @graceleefornyc & @TrippyYang.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

No One Can See The Future: New York Needs Second-Look Sentencing Before More Lives Are Wasted

The Court of Appeals (photo: Mike Groll/Governor's Office)

The past few years have put into stark relief our inability to predict the future. Virologists, epidemiologists, and related medical professionals repeatedly reevaluate their views regarding COVID-19 and its variants. Economists daily revise their opinions about inflation, interest rate hikes, and the likelihood of a recession. Political pundits and pollsters are scurrying to explain why their election prognostications were off the mark. No one can gainsay the limited ability of meteorologists to accurately forecast the weather beyond a few days.

And yet in our criminal courts, judges act as if they have the power to see into the future. It is commonplace for judges to hand down maximum sentences as they emphatically proclaim that the person in front of them is irredeemable and will forever be a threat to society.

In apparent recognition of and response to this judicial hubris, the American Bar Association’s House of Delegates approved a resolution that encourages legislation to provide for judicial “second look” review of all criminal sentences. Such legislation would mandate a reevaluation of sentences where individuals have been incarcerated for ten years, regardless of original sentence or crime of conviction. Notably, the resolution received the unanimous support of the ABA’s Criminal Justice Section Council, a group comprised of judges, prosecutors, and academics, as well as defense attorneys.

The resolution is a recognition that people, including those convicted of serious and often violent crimes, can and do change. Public attitudes about crime also change as evidenced, for example, by the movement to legalize marijuana. Our understanding of behavior evolves as neuroscience now reveals that brain development and the corresponding ability to control impulses and consider consequences continues into our twenties. It is also appropriate, if not imperative, to re-examine sentences simply because it is illogical to think that a sentence once imposed remains just, necessary, and appropriate in perpetuity.

It is also becoming increasingly clear that not all victims or family members of a victim demand lengthy prison terms for the person who caused harm. The restorative justice movement is shining light on innovative approaches to harm and trauma and the needs and desires of those who have been harmed by violence. “Second look” reviews can amplify the burgeoning restorative justice movement by promoting conversation about alternatives to relentless punishment.

Further, second looks are not just about beneficence or mercy. There is much talent that is wasted behind bars. People languish on the inside when they could contribute on the outside as mentors to young people who might end up making the same mistakes that they did at similar ages. They could help repair families and communities that have been devastated by the draconian sentencing of the past several decades. More directly, second look sentencing can return fathers and mothers to support their sons and daughters, and restore sons and daughters to act as caregivers to aging parents. Returning citizens can and do revitalize communities and promote public safety.

To be clear, the American Bar Association resolution does not call for automatic resentencing. It is not a guarantee that anyone will be released. Rather, the potential for resentencing will provide hope for those serving long sentences that they are not necessarily consigned to die in prison. Second looks provide a powerful incentive for incarcerated people to take whatever steps they can to grow and improve, and to confront and address the confluence of factors that led them to where they are, the harm they caused, and what they can do to try and atone.

The ABA resolution is by no means an outlier.

Senator Cory Booker and Representative Karen Bass introduced the Second Look Act in 2019 to permit people who have served ten years in federal prison to petition a court for resentencing. In the meantime, federal court judges are using the First Step Act and compassionate release to find compelling reasons to resentence people given long sentences. Some states have taken steps to rectify past decades of massive sentences that were often motivated by racist tropes like “super predator,” “wolfpack,” and “wilding,” by passing legislation authorizing the right to seek resentencing for those convicted when they were young.

New York is among the states that presently do not provide any mechanism for sentencing review beyond the immediate direct appeal. A bill, the Second Look Act, addresses that omission by allowing judges to review and reconsider excessive sentences. It is long overdue as there are more than 7,500 people serving life and very long-term sentences in New York prisons.

Consider just one example. When Bryon was a young man, he and friends made the rash decision to rob some local drug dealers in upstate New York. In the ensuing chaos, one person was shot in the leg. At sentencing, the judge expressed his view that Bryon was irredeemable, stating, “You should be locked up for a very long period of time to protect other God-fearing, law-abiding citizens . . . you should be kept under lock and key for the absolute maximum period of imprisonment of the time they can keep you there.” Bryon was ultimately sentenced to 50 years.

The passage of time has proven the judge wrong – 21 years later, Bryon has grown into a mature, thoughtful, and accomplished adult. He has not received a single disciplinary ticket for violent conduct. He serves as a GED tutor and is taking college classes. He facilitates alternatives to violence and related programs. He has written apology letters to his victims to take full responsibility for his actions and to express his heartfelt remorse. Recently, he and his wife organized a bookbag giveaway as an effort to try and repair the harm he caused to his community. Without the Second Look Act, Bryon will remain behind bars for decades to come.

Many are familiar with the sentiment expressed by Sister Helen Prejean and civil rights lawyer Bryan Stevenson that no one should be judged by the worst thing they ever did. It seems appropriate to amend the statement – no one should be judged in perpetuity for the worst thing they ever did. It is exactly the “in perpetuity” that forecloses the recognition of redemption and mandates the need for second looks.

***

Steven Zeidman is a professor of law at CUNY School of Law. On Twitter @SteveZeidman.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York City Needs Housing for Everyone, Not More Shelter Beds

Housing (photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Governor's Office)

Faced with an influx of migrants, the main shelter system bursting at the seams, and skyrocketing rents, New York City Mayor Eric Adams declared a state of emergency. The response to this perfect storm has since involved the opening of emergency shelters, building tent intake centers, and even negotiating with cruise line companies to possibly house those in need.

What’s clear is that both our insufficient temporary and permanent housing systems fail those most in need. If we are to turn back the tide on this growing crisis, the path to preventing and solving homelessness runs through creating a new paradigm for housing people.

My tenure leading RiseBoro Community Partnership has taught me that opening more shelters is not the right solution for New York City’s homelessness crisis. Our city’s right to shelter mandate has laid the groundwork for the expensive and inefficient shelter system, but despite billions of dollars in annual expenditures, we are no closer to solving the problem. Meanwhile many tens of thousands of New Yorkers continue to suffer in shelters and on the streets every night. If we are to solve this crisis permanently, we must shift our mindset from a right to shelter to a right to housing.

In a city and nation as wealthy as ours, there’s no excuse to not provide permanent affordable housing to everyone who needs it. Affordable means rent is no more than 30% of a household’s income, the federal standard. Everyone needs an affordable place to live, and when we dedicate such a large share of our resources to shelters over permanent housing, we miss the opportunity to end homelessness.

To be sure, creating a real right to housing in practice will not be easy. It will require a multi-pronged approach that catalyzes new housing production and expands rental assistance for those who need it. The resulting effort may have a large price tag but the city is already spending over $3 billion annually on homelessness. We can’t keep trying to bail water out of this sinking boat with a leaky bucket. We have to plug the hole, and a shift to a right to housing would do that.

For this to be a reality, we need to start by making development in the city cheaper and easier; New York is a notoriously difficult and expensive place to build housing. While there were measures for positive developments proposed in Albany that ultimately failed to pass this year, such as the removal of caps on the size of residential housing development, more needs to be done if New York is to be a place where residents can find an affordable place to live and become thriving members of the community.

To achieve this vision, we should start by reforming New York’s byzantine zoning and land use processes so that all neighborhoods share the responsibility of building additional housing. Next, we must address our outdated property tax system, which puts huge tax rates on large rental properties. Finally, we must invest more in the production of affordable housing, both in terms of capital dollars and in the city agencies that are charged with facilitating development.

Affordable housing is needed throughout the city. Most of New York City’s relatively meager housing growth has been concentrated in a small number of neighborhoods. Since 2010, 10 of the city’s 59 community districts accounted for 47% of new housing permits, and one-third took place in five neighborhoods: the far west side of Manhattan, Downtown Brooklyn, Williamsburg/Greenpoint, Long Island City, and Astoria. We need more infrastructure in disinvested neighborhoods, like the West Farms section of the Bronx, one of the poorest districts in the city. Proposals like Senator Brad Holyman’s — which would shut down racist local zoning laws — would help make this dream a reality.

We also need more creative solutions, like converting hotels and single-room occupancy buildings into affordable housing units, to become the norm. Last year, RiseBoro completed such a project on the Upper West Side for 135 homeless seniors.

Finally, we need broader efforts through legislation to address the housing and homelessness crisis. Senator Brian Kavanagh’s proposal to include $250 million in funding for the Housing Access Voucher Program (HAVP) in the state budget would have been a big step forward, and though it failed this year it should be taken up in 2023. The proposal would support many of the 92,000 New Yorkers across the state currently experiencing homelessness by providing funds to house over 40,000 people in just the first year of the program.

Mayor Adams’ first city budget included $22 billion for housing over the next decade, but that still falls well short of candidate Adams’ $4 billion-per-year pledge for housing.

Creating enough housing is no doubt an expensive proposition, but inaction will cost us far more.

A supportive housing bed and wrap-around services cost $42,000 per year, well short of the $550,000 per year that a bed at Rikers is costing. The difference underscores a real cost-burden of not reducing homelessness, as the unsheltered are 10 times more likely to have contacts with police, nine times more likely to experience jail spells, and twice and three times more likely to require ER services or ambulance rides, respectively.

New York can’t make this shift on its own. The federal Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) that passed, scaled back from the more ambitious Build Back Better plan (BBB), provided $1 billion to the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) for grants supporting climate efforts in affordable housing projects. This is a long way off the $175 billion promised in BBB to build and support affordable housing. This loss of needed federal funding continues to hamstring local efforts to reverse the homelessness crisis and provide enough quality, affordable housing for everyone.

Working at RiseBoro, I see how affordable housing changes people’s lives every day. And my vision of a vibrant and diverse community doesn’t end with housing. Residents must have access to a full range of services that address their needs. Young people must have safety and opportunity to fulfill their potential. It must be a community with healthy food, healthy families, and healthy housing. Without affordable and stable housing, everything else is less effective. Temporary housing only dooms other services to be temporary. We must look beyond the right to shelter and collectively strive toward a right to housing.

***

Scott Short is CEO of RiseBoro Community Partnership. On Twitter @RiseboroNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Criminalized Survivors Deserve Sentencing Reform

Gov. Hochul signs legislation (photo: Darren McGee/Governor's Office)

Although it might sound counterintuitive to some, sentencing reform is necessary to effectively address intimate partner violence and support victims.

To start with, sentencing reform benefits criminalized survivors, victims of violence convicted of crimes related to their own victimization. Sometimes the victims of these crimes are their abusive partners; sometimes the crimes are committed at the behest of, or under duress from, their abusive partners.

Mandatory-minimum sentences are partly to blame for the substantial number of survivors who choose to plead guilty rather than face trial. Confronting the possibility of long terms in prison and “trial penalties” assessed for failing to plead guilty if they are convicted, women take pleas even in cases where they might have credible defenses. They take pleas so that they can get home to their children sooner, to protect their children from having to testify, and because they think they will not be believed.

The Domestic Violence Survivors’ Justice Act (DVSJA), passed in 2019, provides some relief from harsh mandatory minimums and creates a mechanism for reconsidering draconian sentences in some cases. But the DVSJA does not reach all of New York’s criminalized survivors.

For example, in November 2020, a 48-year-old woman who filed a DVSJA application was denied relief despite an extensive history of documented abuse from infancy through early adulthood and despite the fact that her abusive partner (who was the person harmed in the offense) supported her release. The court found she wasn’t a victim of domestic violence “at the time of the offense” (a criterion that must be met to qualify for relief) because it didn’t recognize the psychological abuse by her partner or the cumulative effects of childhood trauma. Since her incarceration she has come to better understand how trauma has affected her life and helps women on the inside grapple with the same issues she’s had to overcome. She is now entering her seventh year of a 16-year sentence.

Cases like this demonstrate why criminalized survivors are calling for sentencing reform, particularly the passage of the Eliminate Mandatory Minimums Act and Second Look Act, both under consideration by the New York State Legislature.

The Eliminate Mandatory Minimums Act would allow judges to consider mitigating circumstances - like abuse and trauma - rather than requiring them to impose a lengthy prison sentence regardless of circumstances. The Second Look Act would allow judges to review and reconsider excessive sentences. Right now, there is no mechanism outside of the DVSJA in New York State to reassess those sentences.

As a law professor who directs a Gender Violence Clinic providing direct representation to incarcerated survivors of intimate partner violence, sexual assault, and trafficking, it is abundantly clear to me that we have spent decades pursuing the wrong solutions to gender-based violence.

There is no evidence that harsh criminal sanctions like lengthy periods of incarceration or mandatory minimum sentences, which require judges to impose specific sentences for particular crimes without enabling them to use discretion in individual cases, decrease or deter intimate partner violence. But there is reason to believe that such sanctions make future violence more likely.

Intimate partner violence is highly correlated with economic hardship. Male under- and un-employment is strongly associated with perpetration of intimate partner violence (and with domestic violence homicides), as is experiencing other economic stress. People with criminal records, especially those who have spent years or decades in prison, have more difficulty finding and keeping work, are often employed in jobs with high turnover and little potential for growth, and earn less than people who have not been criminalized. They frequently live in economically distressed areas, and living in such neighborhoods is also correlated with higher rates of intimate partner violence.

Criminalization also causes trauma. It’s ironic that people who are being punished for violence are sent to places where they are likely to be victims of or witnesses to violence. There are few resources to help incarcerated people recognize and process the trauma that they have experienced, both before and during their incarceration. As a result, when they are released, formerly-incarcerated people take that unprocessed trauma with them back into their communities and their intimate relationships. That trauma can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder, which is highly correlated with the perpetration of intimate partner violence.

Prisons aren’t the way to end intimate partner violence. Yet we continue to pour resources into the criminal legal system, hoping, despite the best available evidence, that somehow incarceration will lead to positive outcomes for people who use violence and for their partners. And we do that despite the knowledge that not only is incarceration not working, but that it is harming those it was meant to protect.

We need to invest in the things that might end violence rather than continuing to throw money at prisons, even “gender responsive, trauma informed” prisons. We need to redirect the billions of dollars that currently go to the criminal legal system into economic stimulus, public health prevention, and communities. And we need to get people out of prison and back into communities, where they can heal, work, parent, and thrive. Yes, even for intimate partner violence, communities not cages is the right policy choice.

***

Leigh Goodmark is a law professor at the University of Maryland where she co-directs the Clinical Law Program, teaches Family Law, Gender and the Law, and Gender Violence and the Law, and directs the Gender Violence Clinic, a clinic providing direct representation in matters involving intimate partner abuse, sexual assault, trafficking, and other forms of gender violence. On Twitter @LeighGoodmark.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Don't Believe the Hype; Bail Reform is Good Policy and Good Politics

Speaker Heastie & Majority Leader Stewart-Cousins (photo: State Senate)

In 2019, Democrats in New York were feeling pretty good. New York City had its first two-term Democratic mayor since the 1980s. Democrats controlled the Governor’s mansion in Albany and every other statewide office. We controlled the State Assembly and the State Senate – both with commanding majorities.

Washington, of course, was a mess. One party was in the thrall of a former game show host, and they were too afraid of upsetting him to get anything done. Say what you will about New York’s one-party rule. But here, at least, there was a real opportunity to make progress for people in need.

So that year, Democrats in Albany took a big swing. They finally reformed the cash bail laws that had, for decades, made a mockery of our criminal justice system and didn't make us any safer. Prior to these reforms, many New Yorkers accused of low-level crimes ostensibly had two options. They could sit in jail while they waited for their day in court, unable to work or prepare their defense. Or they could buy their way out.

But those options were only available to people with money. The ones who could afford to pay up of course did so. But many couldn’t – and so a disastrous, two-tiered criminal justice system took hold: one for the rich, and another for the poor. No New Yorker was any safer for rich people buying their way out, or poor people languishing in jail.

The reforms took away cash bail for low-level offenses, while maintaining it for alleged very serious or violent ones. They reunited countless New Yorkers with their families. They kept people who hadn’t been convicted of anything out of Rikers Island and other hellish jails. They finally made an unfair, racist system a little fairer.

And then the storm came.

I’m a longtime political consultant in New York, and I’ve never seen anything like it. Republicans and their media allies responded with manufactured rage from even before the law was changed and never stopped. They ignored the practicality of the reforms, which kept those accused of the most violent crimes in jail and leveled the playing field for everyone else. Every crime committed anywhere, by anyone, was suddenly a direct result of bail reform. They spent millions of dollars running bail-related attack ads before the 2020 elections — an attempt to terrify New Yorkers and benefit from a national crime spike.

Republicans told anyone who’d listen that voters would punish Democrats for their overreach and take away their 40-seat majority in the State Senate.

When the dust settled that November, Democrats had won 42 seats in the 63-seat Senate. The majority became a supermajority.

Maybe New York Republicans quietly blamed their failed, unpopular president. But they might have had a clue what voters were really experiencing if they had looked at the data. Bail reform was working. Study after study found no correlation between bail reform and any increase in crime. The New York Post examined NYPD data on gun violence and found that less than 1% of the 11,000 people released from jail in early 2020, when bail reform first went into effect, were involved in a shooting. More recently, as Nassau County leaders falsely blamed any crime on bail reform, their own study found that few are re-arrested.

Instead of following the data, Republicans tripled down.

Lee Zeldin’s run for governor was the darkest campaign in recent memory. He talked about bail reform almost every day. And he had help; Republicans poured millions in campaign donations to groups supporting him.

With no game show host to drag them down, Republicans were even more confident this year. They were sure a red wave would crash on New York – one that would cut a gash in the Assembly and Senate majorities, and maybe even sweep Zeldin into the Governor’s mansion.

Once again, it didn’t happen. Democrats won 41 seats in the State Senate this year. With one race heading to a recount, it could be 42. The Assembly supermajority is as commanding as ever. And Lee Zeldin lost by hundreds of thousands of votes.

Here’s what that means: after three years of predictions that bail reform would sink those who passed it, the Democratic Party has gained representation in state government.

Crime, of course, is still an animating issue for voters across the state. And Republicans likely won tight races for the House of Representatives by exploiting it. Many of those races were winnable; it’s hard to escape the feeling that we should have done even better. But the House of Representatives didn’t pass bail reform. Democrats in the State Legislature did – and New Yorkers, in two straight elections, ignored a tsunami of persuasion to reward them for it.

Politics is a tough business. But one thing remains true: voters will support you for doing the right thing, no matter how much money is spent to convince them not to. New Yorkers have asked for solutions on public safety, not scare tactics. They’re ready to address what’s really driving crime. Ignoring the data gets us nowhere.

With next year’s legislative session around the corner, Democrats will have another chance to enact bold changes. There’s plenty left to do; our criminal legal system still targets people of color and the poor, and advocates are bursting with ingenious, practical solutions. Democrats in Albany should give those policies a fair hearing, and act decisively. The politics will work in their favor. Be brave.

***

Jason Ortiz is a Democratic political consultant and the co-founder of Moonshot Strategies. On Twitter @hotroddy95 & @MoonshotNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York City’s Largest Group of Drivers is Being Left Out of the Electric Vehicle Conversation

Gov. Hochul drives an electric vehicle (photo: Governor's Office)

A recently-launched pilot offers Uber, Lyft, and other for-hire-vehicle drivers the opportunity to trade their gas-powered vehicle in for an electric Tesla. An experienced, high-earning Uber driver, Angelis, jumped at the opportunity – but within a week returned the Tesla for a traditional black SUV. He loved driving the car and said his customers raved about it. But as a resident of the Bronx, it was not feasible for him to keep it — going electric meant he had to drive 35 minutes twice a day to a charging station and wait there for a charger to open. Because he drives so much, he spent almost as much on charging as he would on gas. So Angelis will be back in a gas-powered SUV until New York is ready to support his transition to an electric vehicle.

The news is filled with exciting investments from Washington and Albany in New York City’s electric vehicle future, but this effort is inadvertently ignoring the most critical subset of drivers who can have the largest impact on our city’s environmental footprint. For-hire-vehicle (FHV) drivers, like those on the Uber and Lyft platforms, outnumber yellow cab drivers 8 to 1.

New York State received federal backing for 60,000 new highway chargers, as well as an expanded supercharger network in Manhattan or near the city’s airports. This approach is geared towards leisure and commuting drivers, leaving FHV drivers in the dust.

FHVs have become a central part of the city’s transportation system. Among other benefits, FHVs supplement public transportation systems in the outer boroughs where buses and trains run less frequently or not at all. Certainly, the last thing New York City needs is more vehicles on the road — encouraging leisure or personal-use electric vehicles and charging support alone will only increase congestion.

As CEO of Voyager Global Mobility, the leading provider of for-hire vehicles in New York City, I work to support thousands of drivers, providing them with safe, up-to-date vehicles and support. I hear directly from drivers every day, and it has become clear that the key is to convert existing FHV-licensed vehicles to EVs rather than clogging our streets with new vehicles as Uber and Lyft aim to achieve their EV commitments.

There are 90,000 FHV licenses operating in the five boroughs of New York City, providing in sum an average of 600,000 rides a day. Luckily, New York is the most regulated city for the for-hire-vehicle industry in the world, which means drivers pass more rigorous screening, vehicles are inspected more often, and overall, FHVs are safe and reliable. Due to these extremely high standards and the continued need for professional drivers, many of these 90,000 New Yorkers have turned driving into a career, and their cars are their keys to a steady income and a foothold on the economic ladder.

The overwhelming majority of FHV drivers use gas-powered cars — only about 615 FHVs in all of New York City are EVs. It’s not that the mobility industry doesn’t care about the environment or resists EVs. The challenge is that the charging system does not support an equitable EV transition for drivers.

We cannot expect these hard-working New Yorkers to trade in their current vehicles — their most important revenue-generating asset — for EVs that will require inconvenient and expensive charging. They cannot waste time that could be used to make money to drive across the boroughs or along the highway to wait in long lines for a full charge (which already takes 40 minutes on its own).

Despite being home to 40% of New York City’s FHV drivers, Queens has just 16% of the city’s chargers. Manhattan is home to just 8% of New York’s TLC-licensed drivers, but the disproportionate concentration of chargers there primarily benefit residents that own individual electric vehicles, not the working-class drivers of the outer boroughs who rely on this infrastructure for their livelihoods.

New EV charging stations need to be concentrated in the outer boroughs, where FHV drivers actually live. FHV electric vehicles have to charge three times more frequently than personal cars, which are used much less frequently for fewer miles at a time.

As it stands, the city’s public charging network is tight and poorly distributed throughout the five boroughs. The entire city has roughly 2,000 public chargers (of which only about 120 are fast charging) for its nearly 6,000 EVs on the road, and 56% of those chargers are concentrated in Manhattan. Vehicle subscription companies, like Voyager Global Mobility, can pinpoint exactly which neighborhoods have high numbers of drivers. There are certain zip codes in Queens with 100+ clients renting for-hire-vehicles just from us — those are the areas where we need to focus our expanded EV charging infrastructure efforts.

Further, we need to ensure that charging is affordable outside of the congested areas of Manhattan. Recently, the TLC announced discounts at NYC Department of Transportation charging hubs, which is extremely helpful. However, it only covers two hubs, neither of which are in the Bronx or Brooklyn.

We need to acknowledge that this city is not set up for anywhere close to 90,000 gasoline cars to be converted to EVs. If not now, when? EV investments must focus on the needs of FHV drivers. We’re ready for solutions and we invite the city, the state, and other partners to come along for the ride.

***

Sam Jurkowicz is a former Uber driver and the CEO of Voyager Global Mobility, the leading provider of vehicles and services for NYC’s growing for-hire-vehicle mobility needs.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

To Truly Pursue Equity in Marijuana Rollout, Cannabis NYC Needs a Makeover

Announcing 'Cannabis NYC' (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

It’s no secret that the War on Drugs has disproportionately impacted people of color in the United States, leading to the scourge of mass incarceration. In 2010, the ACLU released an analysis on cannabis convictions, showing that Black people in New York state were 4.5 times more likely to get arrested for possession of cannabis than white people even though both groups use it at the same rate. Ten years later, this phenomenon hasn’t changed. In 2020, the NYPD’s crime statistics data reported that people of color in NYC made up 94% of arrests and summonses issued for low level cannabis violations.

It has been over a year and a half since cannabis was legalized in New York. Heralded as the most equitable cannabis legalization effort in the United States, the Marijuana Regulation & Taxation Act (MRTA) focuses on groups that were impacted the most by cannabis prohibition – namely black and brown communities. However, NYC’s program, Cannabis NYC, has not invested nearly enough into communities that have been hurt the most by cannabis prohibition. As New York state implements its recreational cannabis licensing process with the first 36 licenses, and NYC provides a meager $4.8 million investment through its program Cannabis NYC, we must ask ourselves: is this really the best we can do?

In theory, New York state has instituted impressive measures to uplift social equity entrepreneurs, or individuals with prior cannabis-related convictions seeking to open a recreational cannabis business. Some of these initiatives include setting aside 50% of licenses for social equity entrepreneurs to open recreational dispensaries and a $200 million investment fund that will underwrite costs associated with leasing retail spaces and loan assistance. Despite the support on paper, the administration is moving too slowly in practice. The aforementioned retail spaces have not yet been secured and the fund has not raised the promised $150 million in seed funding. With Governor Hochul’s announcement that only 36 legal cannabis dispensaries will be in operation by the end of the year, there is reason to worry about how social equity entrepreneurs will be supported in this disorganized plan.

On the city side, there have been insufficient investments in social equity entrepreneurs. The Adams administration created and tasked Cannabis NYC with providing services including license application assistance, outreach to communities that are eligible to apply for social equity licenses, and workforce development training for the cannabis sector. Even with these minimal responsibilities, Cannabis NYC barely fits the bill. Since Cannabis NYC was only established three months ago, most of the application support was falling on the shoulders of nonprofits and law firms, sometimes costing individuals up to $10,000 in fees.

Additionally, cannabis businesses are a costly endeavor with a $2,000 application fee for a recreational license and high-cost barrier to enter the industry. Start-up costs for retailers can range between $250,000 - $750,000. The Drug Policy Alliance found that in 2019, the city spent almost $100 million alone on policing drug arrests and violations. As reparations for these egregious oppressive measures, Cannabis NYC must expand its supportive services to provide financial assistance to social equity entrepreneurs to cover the recreational cannabis license fee of $2,000

and underwrite a fraction of the start-up fees when the state inevitably moves too slowly to provide assistance. Cannabis NYC must also bolster their application assistance for all New Yorkers seeking their services.

The recent increase in crime may make New Yorkers less sympathetic toward those with prior convictions, leading them to object to additional supportive measures. In a recent poll, 70% of New Yorkers reported concern about feeling less safe since the pandemic due to increased crime rates. However, research has shown that access to employment is the most important factor in reducing recidivism. Even for individuals who do not support cannabis usage, an investment in communities with past convictions will keep them out of the cycle of crime and the prison system, thereby reducing crime rates across the city.

The NYC Comptroller office projected that revenue from cannabis sales in NYC could reach as much as $336 million per year. In a city where the operating budget is $101 billion, this may seem like a drop in the bucket. However, when put into perspective, this amount shows how much NYC will gain from the cannabis industry, while investing just over 1% of projected revenues in social equity entrepreneurs who have been harmed by the city’s criminalization of cannabis. As reparations for the damages that cannabis prohibition ravaged upon Black and Brown communities in NYC, the mayoral administration must ensure social equity entrepreneurs make their mark in this highly profitable industry. One small step is by increasing financial support to social equity entrepreneurs through underwriting their start up business costs and covering the $2,000 retail dispensary license application fee.

***

Arielle Kaye is an MPA student at NYU specializing in International Development Policy & Management.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Reason to be Thankful This Holiday Season: New Law Empowers Sexual Assault Survivors

Gov. Hochul signs the Adult Survivors Act (photo: Mike Groll/Governor's Office)

On Thanksgiving, survivors of sexual abuse in New York had something to be truly thankful for. November 24 marked the opening of a one-year period when, under a new law, survivors can file a civil claim against the person who abused them and any institutions that enabled the abuse, no matter how long ago the abuse happened.

This law, the New York Adult Survivors Act (ASA), presents a watershed moment for survivors; it invites and empowers them to reclaim their narratives, end their silence, and hold those who harmed them accountable.

The ASA was born of the recognition that for too long, survivors of sexual abuse were either disbelieved, shamed, or blamed for the abuse and left with little support to recover from the trauma left in its wake. After all, until 1984 it was legal in New York for a husband to rape his wife. And sexual harassment was not even considered a violation of federal civil rights law until 1986. Even once the laws became more protective of survivors, historically short statute of limitations periods meant that by the time survivors were able to speak their truth, it was often too late to sue the abuser. In reviving expired claims, the ASA also revives survivors’ chances for a measure of justice and acknowledges the reality that processing sexual trauma takes time.

Ending silence, secrecy, and shame around abuse is why laws like the ASA, the Child Victims Act before it, and the anti-SLAPP law New York passed in 2020, are so important. SLAPP lawsuits (or Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation) have long been used by abusers to torment and silence survivors. Formally named in the 1980s and in use well before that, a SLAPP suit may look like an ordinary claim for defamation, nuisance, or invasion of privacy but its purpose is to intimidate and muzzle the person on the other side. Abusers leverage SLAPP lawsuits to tie up survivors in lengthy legal proceedings in an attempt to drain them of their financial and emotional resources while fighting these baseless claims.

This tool was famously used by Johnny Depp against Amber Heard to punish her for publicly telling her story of intimate partner violence in the Washington Post, leaving her silenced and impoverished in the end. The publicity surrounding that case has undoubtedly had a chilling effect on survivors considering coming forward to speak out about the abuse they suffered, especially if their abuser is famous, powerful, or rich.

The SLAPP suit is also the tool that was wielded against me (Grace) by my ex-husband, who sued me for defamation after I spoke out on my podcast about abuse in the entertainment industry and the challenges facing victims in the justice system. But thanks to New York’s anti-SLAPP law, my story has a happier ending than Amber’s: earlier this month, a court threw out the lawsuit against me and ordered my ex-husband to pay the attorney fees and costs I incurred while defending myself.

For too long, short statutes of limitations for filing abuse claims and the threat of SLAPP lawsuits conspired to keep survivors quiet. And that silence only benefited abusers, allowing many to suffer no consequences and go on to abuse others. But taken together, New York’s anti-SLAPP statute and the one-year Adult Survivors Act revival period create the opportunity for a full-throated telling of survivors’ stories to fill the courts with accountability as its final chapter. And that is something to be thankful for.

***

Grace Aki is an actor, playwright, and comedian in New York. Laura Edidin is Of Counsel at Wigdor LLP, a former sex crimes prosecutor, and domestic violence victim advocate. On Twitter @itsgraceaki & @WigdorLaw.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York Universities, It’s Time to Tear Down That Wall

Fordham University behind the wall (photo: Brian Martindale)

New York universities are walling people out. Major private institutions across the city are surrounded by gates, but not because they are in the most dangerous neighborhoods. Rather, it appears that largely white student bodies are being walled off from their surrounding communities because of unfounded fear of racial others.

Columbia University, in a neighborhood adjacent to Central Harlem, is blockaded on every side with a security force keeping watch on all who enter its narrow gates. St. John’s University, in Queens’ Hillcrest neighborhood, is peppered with turnstiles, gated parking lots, and signs marking it as “Private Property.” Fordham University’s Rose Hill campus in the Bronx is similarly locked-down, separated from the surrounding community by wrought iron and chain link fences, at places with barbed wire and stone walls. The only way in, with few exceptions, is by scanning a school ID past a staffed security booth or full-height turnstiles.

Standing in contrast is New York University, located in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village. NYU is a decidedly urban campus, built into the fabric of the city, with the public Washington Square Park serving as its primary quad.

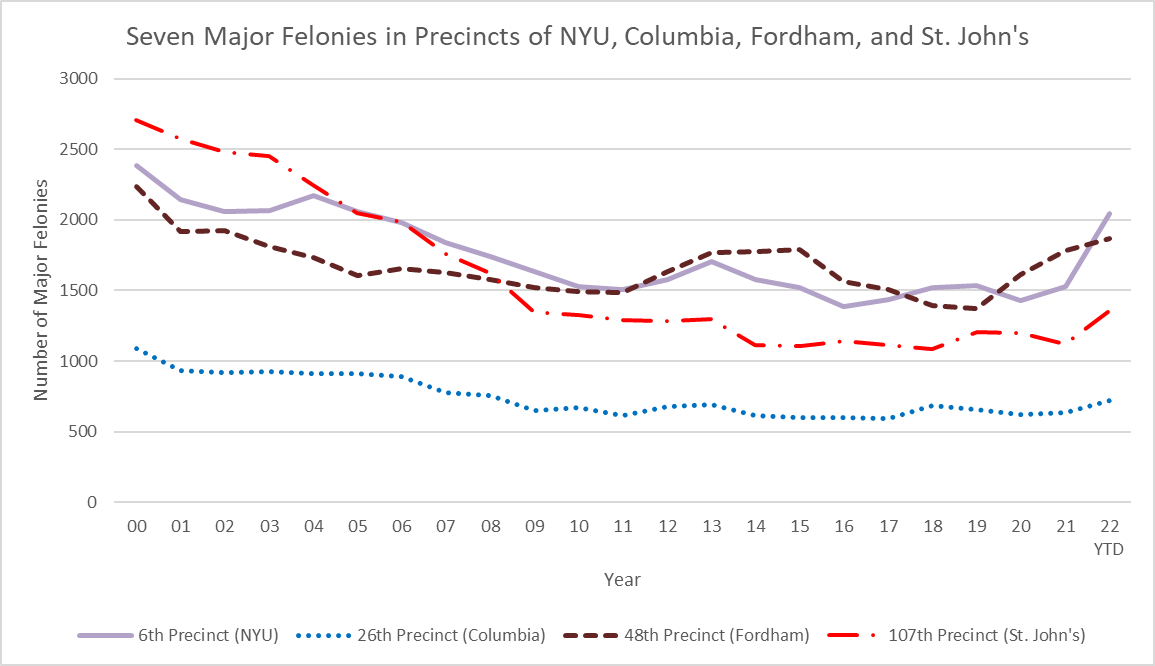

What makes NYU different? Gut instinct might suggest NYU is in a safer neighborhood so it doesn’t need a gate. But it turns out the universities that believe they need to wall out crime are actually in safer communities. A quick look at crime statistics since 2000 shows that among the four universities, NYU’s precinct has had the highest or second highest number of major felonies every year. The area around Columbia has had half as many major crimes as the area near NYU every year for the last 22. This year, NYU is on pace to have the highest crime again, with 2,045 major felonies as of November 13, compared to 1,869; 1,357; and 720 for Fordham Rose Hill, St. John’s, and Columbia, respectively. If NYU can manage without a wall, the others can as well.

There is, however, a key factor that distinguishes NYU from the three other universities: the racial makeup of the neighborhood. In 2019, Greenwich Village/Soho was 14% Black and Hispanic, while Columbia and Fordham are in neighborhoods that are majority Black and Hispanic. St. John’s is in a neighborhood that is 37% Black or Hispanic and also has a significant Asian population, at 31% of residents.

It is no secret that perceptions of safety are often related to race. A 2001 article by researchers at Florida State University suggests the presence of racial “others” lead to greater fear of crime, and another 2018 article suggests such “white fear” leads to continuing racial segregation. The universities in predominately non-white neighborhoods, though they are safer, appear to be using walls to shut out their neighbors because of this fear.

The shutting-out also shows itself in university enrollment. While 96% of Fordham’s Bronx neighborhood is Black or Hispanic, only 18% of its Bronx campus students were Black or Hispanic in 2020. Columbia had a mere 13% Black or Hispanic population at its Morningside Heights campus in 2020 compared with 52% in the neighborhood. St. John’s Queens campus is closer, with 31% Black or Hispanic students compared to 37% in the neighborhood, but Asian representation is only 16% compared with 31% of neighborhood residents.

These disparities are significant. They mean that the walls are working.

But what’s the big deal anyway? Why should anyone care if college campuses bar their neighbors from entering? Isn’t it better to wall off the students and keep adolescent antics from bothering neighborhood residents?

While some imagine benefits, walls correspond to serious setbacks for neighborhood development. In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, urbanist Jane Jacobs writes of boundaries in cities as “barriers,” creating “vacuums.” They set in motion “an unbuilding, or running down process.” If people can't walk through an area because of a university wall, they won’t shop at the stores nearby or visit the amenities. Stores close, sidewalks become empty, and safety decreases with fewer eyes on the street. Campus walls aren’t neutral in their neighborhoods. They actively oppose economic development and public safety.

A short walk up Amsterdam Avenue toward Columbia’s campus can show what happens to a university isolated from its neighborhood. Just south of campus, Amsterdam is vibrant, with shops and restaurants and people strolling the sidewalk. Parks and churches dot the avenue. But as you get closer to campus, the stores and restaurants are replaced with imposing walls and the sidewalks become lonely. As you continue past campus, the vitality reemerges. But beware: if you turn down 120th Street, along Columbia’s northern wall, the same loneliness awaits you. The campus barrier smothers development, and if it were removed the neighborhood would have breathing room to improve further.

What’s even more concerning than neighborhood vitality is the educational opportunity these walls prevent. By sending the message that neighborhood residents do not belong on prestigious college campuses, the walls are minimizing the possibility of upward mobility that accompanies such education, continuing the cycle of poverty so often persistent in non-white communities. The United States has always had racial disparities in higher education, with an unfair number of white students able to attend college compared with Black and Hispanic students. While the gap between who starts college is decreasing, there are increasing racial gaps in who achieves a college degree in the U.S.

There are also gaps in the quality of college that people of different races attend. Columbia, Fordham, and St. John’s are among the best-ranked private institutions in New York City. The racial disparities that persist because of their literal and figurative walls are not blocking students from just any college education. Walls prevent under-resourced populations from the education with the most possibility for economic uplift, especially as compared with two-year programs and community colleges.

Even if the walls don’t come down tomorrow, these universities owe it to their neighborhoods to be active and supportive agents to tear down the invisible walls that separate the institutions from their neighborhoods. They should use local vendors for university needs to support the wellbeing of neighbor businesses. They should invite community members to be a part of meetings with politicians or other power players that come to speak on campus.

They should leverage their influence to advocate for the needs of their neighborhoods, and to do so they must really know their neighbors. They need more educational support programs like CSTEP to support non-white and economically disadvantaged students, especially from the nearby community. While these institutions have made strides in this area, more must be done.

Then, it’s time to tear down the physical walls. We ought to be doing everything we can to help students of color envision themselves at our institutions of higher education. Because if they can’t even imagine walking the campus, how could they ever imagine walking the graduation stage?

***

Brian Martindale is a Jesuit seminarian and master’s student in urban studies at Fordham University.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.