Vote ‘Yes’ on Question 2 and Send Albany a Message

(photo: Edwin J. Torres/NYC Mayor's Office)

This Election Day, New Yorkers have an opportunity to vote for ethics in government. You won’t see the words “anti-corruption” or “integrity” on the ballot, but make no mistake – these essential elements of trust in government are at the core of Ballot Proposal 2, which will be put before voters on November 7.

Proposal 2 -- which can be found on the back of your ballot with two other questions -- seeks the public’s approval to amend our state constitution to “allow a court to reduce or revoke the public pension of a public officer who is convicted of a felony that has a direct and actual relationship to the performance of the public officer’s existing duties.”

If a majority of New Yorkers vote “yes” on Proposal 2, no longer will pension dollars automatically go to felons sitting in jail who have thoroughly violated their oaths of office. For crimes committed after the enactment of the constitutional amendment, not only would taxpayer money be saved, but also the message would go out that the Empire State no longer tolerates – and bankrolls – corruption.

When I proposed a pension forfeiture constitutional amendment during my first year in the State Assembly, 2013, I was told there was no chance of this idea passing in Albany. Criminal conduct among elected officials was all too common. Many ethics reforms had gone nowhere in our state capitol. The State Assembly was led by Sheldon Silver and the State Senate headed by Dean Skelos, two men who would be forced from office after being embroiled in corruption scandals. But broad backing from the citizens of New York helped this idea overcome many hurdles, leading to the 2016 and early 2017 legislative passage of this proposed constitutional amendment, which placed the measure on this November’s ballot.

A vote in favor of Proposal 2 would send a clear message to state officials that we no longer tolerate corruption, forewarning them of what is to come if they violate the public trust they’ve sworn to uphold. Proposal 2 empowers voters to respond by putting ethics reform directly in our state constitution. (Don’t confuse this vote with the vote on Proposal 1, which asks whether New York State should hold a constitutional convention – a convention would likely deal with many other topics beyond ethics reform.)

If voters overwhelmingly support the pension forfeiture amendment, Proposal 2, New Yorkers will then be on firm footing to pressure the State Assembly and Senate to take up other needed reforms. These should include closing the “LLC loophole” that allows the use of limited liability corporations to funnel massive amounts of cash into election campaigns, and banning companies and individuals bidding on government contracts from making campaign contributions to state elected officials who have authority to approve or reject those bids.

A big win this Election Day for Proposal 2 would demonstrate that the public wants ethics reform. Too many people in Albany believe that ethics reform is something voters don’t care about. Prove them wrong – vote YES on Proposal 2.

***

David Buchwald is a New York State Assemblyman from White Plains. He represents over 130,000 residents of Westchester County. On Twitter @DavidBuchwald.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Open Primaries and Overcoming the Racial Divide the Parties Prop Up

(photo: William Alatriste/City Council)

Today the dominance of the two major parties has frozen the country’s political development along a racial divide: the Republican Party uses law and order, tax cuts and anti-immigrant rhetoric to capture white voters, and the Democratic Party depends on high black voter turnout to win elections, while failing to address the ongoing inequality between people of color and white people. Pollster Cornell Belcher has found that 63% of black people feel taken for granted by the Democratic Party. The current highly partisan political environment is producing both government dysfunction and a general sense of dread that the county is moving backward.

The American people have been so manipulated and divided by politicians and our political process so over-determined by two-party control that for ordinary people of good will to meaningfully come together requires a wholesale break from politics as usual. We should not confuse multiracial solidarity—when people of different races come together to fight for a common goal—with the dynamic of political party constituency groups such as African-American, Latino, LGBT people, and women making demands within the Democratic Party and fighting each other for the attention and resources of the party and its elected officials.

I recently had a conversation with a close friend whose history is very different from my own. We agreed that perhaps the most dangerous effect of the current political environment is that people of different races are being pushed further and further apart. My friend Nancy, who is white, grew up under segregation in the 1950s in small towns all over northeast Arkansas. As a child, she "experienced and witnessed and joined the fight for integration in the South.” Fifty miles from her home and 20 years earlier, the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union was formed, a federation of tenant farmers that united black and white sharecroppers to reform the system of sharecropping and improve the lives of all its members. Women played a key role in the development of this organization. As we talked about this, Nancy said to me, “I think this history is good to have in our tool box. I certainly will not forget where I come from. This history is important to me because I witnessed the fight for integration in the South.”

I grew up in the black community of south Philadelphia in the 1960s. My grandmother, Adell Chandler, owned and operated a large soul food restaurant that was open 24 hours a day and was a pillar of the cultural and social life of the community. She was a supporter of the civil rights movement and she encouraged me to become a doctor. I dreamed of becoming a doctor who could be a role model and help transform the conditions of the black poor.

I remember hearing Dr. King’s voice on the radio. It was his unbending stance for nonviolence, his courage, his willingness to sacrifice his life, his humble yet soaring commitment to fight against poverty, racism, and war that inspired people of all colors to take a stand. When Dr. King asked people to come to Selma to march for voting rights for African-Americans, Americans from across the country responded.

Nancy and I are both independents who are activists in the progressive wing of the independent political movement founded jointly by Dr. Lenora Fulani—who ran for president as an independent and in 1988 became the first woman and African-American to appear on the presidential ballot in all 50 states—and Jackie Salit, the author of Independents Rising and the president of Independent Voting, the country’s largest network of independent voter activists. These two women are working to build multiracial solidarity by creating independent tools to revitalize American democracy and transform our political culture to one of inclusion and opportunity for all.

Multiracial solidarity stretches throughout American history from the founding of the country in which black soldiers fought alongside white soldiers in the Revolutionary War, to the anti-slavery movement of black and white abolitionists who worked together and built the Underground Railroad. And examples from the Civil War, when Union officers like Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Robert Gould Shaw led regiments of black soldiers, many of whom were recently emancipated slaves (Shaw died fighting alongside his black troops).

A little-known demonstration that preceded the modern civil rights movement was led in January 1939 by Owen Whitfield, an African-American preacher and organizer of the Southern Tenant Farmer’s Union. He led the Missouri Sharecropper Roadside Demonstration, where black and white homeless sharecropping families camped out on the side of the road in the dead of winter as a means of getting the government’s attention to the vast poverty and injustice for tenants who were pushed off the land by planters. In the face of the segregated south they stayed together and though the public demonstration was crushed by the state police, it remains an inspiring example of poor people crossing the racial divide to stand in solidarity and demand justice.

Today in most states there is a political divide between the Democratic and Republican parties that corresponds to a racial divide in which people live in segregated communities.

A recent New York Times article on the obstacles to getting the governor, the mayor and the state Legislature to agree on a plan to invest in New York City's badly aging subway noted: "The future of the nation's busiest subway system, which has become engulfed in crisis, could well depend on New York State lawmakers…who live hundreds of miles from the city.”

The distance between New York City and much of the rest of the state is not only geographic, it is also a racial divide that is sustained by the parties. Though people of color live throughout New York State and New York City is racially and economically diverse, downstate New York City where more people of color live is dominated by the Democratic Party and upstate New York, where fewer people of color live, is dominated by the Republican Party. This arrangement maintains the parties’ duopoly control and both parties have carefully protected it, including through gerrymandering of districts.

In a closed primary state like New York, where party insiders control the process of voting, only party members are allowed to vote in the corresponding primaries. Over 3 million “independent” voters are excluded from primary voting as a result. Of those, 35% are millennial voters, 33% are Asian voters, 20% are Latino voters and 18% are African-American. Under these exclusionary, partisan elections, the New York State Legislature has proven itself to be one of the most dysfunctional and corrupt state governments in the country.

This November, New Yorkers will have an opportunity that only comes around every 20 years: to vote “yes” on a constitutional convention, through a ballot referendum question on Election Day, and break free of the constraints to begin a process that puts reforms such as open primaries in the New York State Constitution.

In contrast, California has nonpartisan open primaries, passed by the voters in 2010. The impact has been significant. People of color are winning some local elections in majority white districts and California is leading the nation in passing effective government reforms. Moreover, under its open system two women - one African-American and one Latino -- faced off in the general election for a U.S. Senate seat in 2016. Kamala Harris, the African-American of the two, won to become the junior senator from California.

Americans can only truly come together if we can build a democratic process that empowers all voters outside the framework of a political party. Nonpartisan structural reform such as open primaries provides that opportunity.

Forty-three percent of American voters now self-identify as independents and many people, no matter how they identify, want the chance to vote and to participate in politics in new ways. The government dysfunction we see in Washington will not be reformed from within the parties. The future of our democracy depends on the American people carrying it forward. Those stepping outside the parties are leading the way to build bridges rather than walls.

***

Dr. Jessie Fields is a Harlem based physician, an organizer with the New York City Independence Clubs and a board member of Open Primaries, which advocates for nonpartisan election reform.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

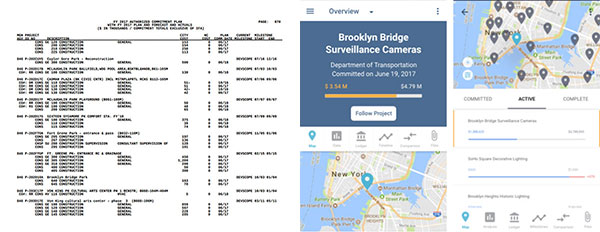

A More Transparent City, with A Page for Every Capital Project

Construction in Corona Plaza (photo via DOT)

Few things impact the lives of New Yorkers more than the city’s “capital projects.” These projects create, maintain, and improve the infrastructure New Yorkers use every day, including: streets, bridges, tunnels, sewers, parks, and so much more. In 2018, the capital budget will be $16.2 billion, approximately 17% the size of the city’s $85.2 billion “expense budget.” What are these projects? How can you find out about them? It’s not easy, but it should be.

The Capital Budgeting process is a complex endeavour. The City maintains a 10 Year Capital Strategy that it updates every two years, and an Annual Capital Budget that is passed every year by the City Council, and a Capital Commitment Plan that is prepared by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) three times a year, which outlines precisely how and when funds are being allocated to agencies on a project by project basis. The Commitment Plan is the most interesting because it’s the closest to the reality of how the city is planning to spend our money. It comes in four “volumes” of PDFs containing 2,162 pages of table after table of information describing nearly 10,000 different projects. Printing this out results in a stack of paper about one foot tall.

In 2017, why isn’t all this information in an easy-to-use spreadsheet or database? The only reasonable answer is that the city doesn’t want the public to scrutinize this information too deeply.

Fortunately, recent advances in technology have made it much easier to turn PDFs into spreadsheets, and spreadsheets into web applications. And that’s what I’ve done at projects.votedevin.com, where you can now find a web page for every single capital project, organized by agency and sortable by project’s cost. Of course, our ability to display useful information about projects is limited by the information in the capital budget reports - but there’s more than enough information to pique any budget conscious New Yorker’s interest.

Here’s an example: Project HBMA23216 from the DOT is a $312 million construction project for the “Promenade over FDR E81st - 90th St Bin 2232167.” That’s a lot of money for a promenade. By Googling the project’s name, description, and various internal codes (FMS Number, Budgetline and Commitment Codes) we can find a lot more information, like the RFP Notice, proposed architectural plans, and more.

As you browse the budget, sorting the most expensive projects by agency, more questions arise: Why does the City’s 311 system need a “Re-Architecture” that costs over $20 million this year? Why isn’t the press reporting the over $120 million in renovations planned for the Brooklyn Detention Center (search BKDC)? Why does the “Vision Zero Street Reconstuction” [sic] go from $2 million in 2018 to $100 million per year in 2021-2023?

I’m sure good answers exist for these and other, more probing, questions. These projects are, after all, funded by us taxpayers. Making this information more accessible would not only create more opportunities for civic engagement, it would also allow the public, journalists, academics, and others to serve as watchdogs, which might result in millions of dollars of identifiable cost savings.

A quick trip to the New York City Charter reveals that the City is required by law to document its capital projects in a very specific way. Presumably the City follows its Charter, which means this information exists, so shouldn’t the city share more of it? Cost shouldn’t be the reason we don’t have access to this information. If the City spent just 1/100th of 1% of the capital budget on public documentation, they could easily fund an exceptional website with a team of data organizers and content publishers who could keep it up-to-date.

What would that website look like? It would certainly have a lot more information than what the city currently publishes in its PDFs and on their “Capital Project Dashboard,” which offers very little additional information about the 189 “active projects over $25 millions.”

Imagine if the City maintained a web page for every capital project that contained all related public information: project status, project scope summaries, location on a map, lists of hired contractors and their fees, and an activity log so we, the people, could watch as projects move through their various stages. Now that’s the types of transparency we should expect from our city government!

Who has the power to make this information public? Certainly the Mayor's Office, but it's easy to see why it doesn't. The Mayor is responsible for directing the people and agencies leading these projects, so creating more avenues for additional scrutiny, which could easily lead to bad press, is hardly a priority. Fortunately, New York City’s Public Advocate, which is an entirely independent office, has some statutory jurisdiction within the Capital Budget process and could force the city to better document the capital budget.

Section 216 of the New York City Charter states, “Upon the adoption of any such amendment by the council, it shall be certified by the mayor, the public advocate and the city clerk, and the capital budget shall be amended accordingly.” While I’m not a lawyer, it sounds like the Public Advocate could threaten to stop certifying amendments to the budget until the city releases a database of all capital projects with additional information to help New Yorkers better understand how their tax dollars are being spent.

That’s precisely what the Public Advocate should do, and as a candidate running for that position, I commit to making that demand when elected. It’s up to you, the public and the media, to ask other Public Advocate candidates how they’d use their oversight power over the Capital Budget. Will they also pledge to demand "A Page for Every Project"?

Until the city offers a page for every capital project, I’ll will keep updating projects.votedevin.com so New Yorkers can learn more about what the city does with our money. It’s a tough job but somebody’s gotta do it.

(image of the city's capital commitment plan vs. our website)

…

Devin Balkind is a candidate for New York City Public Advocate. He is also the President of the Sahana Software Foundation, a nonprofit organization that produces the world’s most popular open source software platform for disaster management. On Twitter @DevinBalkind.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Where Mayor De Blasio Must Take Vision Zero Next

Mayor de Blasio and Vision Zero (photo via DOT)

Vision Zero is a singularly successful legacy project for Mayor Bill de Blasio. It would be more successful if his safety projects were decoupled from parochial interests.

In 2011, Transportation Alternatives and the Drum Major Institute published Vision Zero: How Safer Streets in New York City Can Save More Than 100 Lives a Year, the first Vision Zero report in the United States. In 2013, thanks to that report and assiduous follow-up advocacy by the victims’ group Families for Safe Streets, candidate de Blasio adopted Vision Zero as a key campaign promise, pledging to eliminate traffic fatalities by 2024. Many saw this as an impossible goal, especially after the impressive safety strides made during Mayor Bloomberg’s three terms in office. How much further could traffic fatalities really decline?

Mayor de Blasio officially launched Vision Zero at PS 54 in Woodside Queens on January 15, 2014, just two weeks into his term. Since then, traffic fatalities in New York City have declined 23%.

Whereas 290 used to die annually in New York City traffic crashes, today that number is about 240. It is difficult to overstate the significance of this success. If the pre-Vision Zero average annual traffic death rate had continued over the past four years, 122 more New Yorkers would be dead today and many thousands more would have been seriously injured. Considering that nationwide traffic deaths are up 17% over this same four-year period, the mayor’s effort is even more impressive. If New York City’s Vision Zero program were a vaccine, it would be heralded as a miracle drug.

What is more remarkable is how little the streets have changed to achieve this massive reduction. While the Mayor has championed transformative redesigns of many notoriously dangerous streets, the vast majority of known dangerous streets have yet to be affected by the DOT’s modern menu of traffic safety fixes such as pedestrian friendly traffic signal timing and protected bike lanes.

Queens Boulevard, the former “Boulevard of Death,” which used to kill a dozen New Yorkers every year, has not seen a single fatality in the past two years since being redesigned. Yet there is a backlog of more than 150 dangerously-designed streets and nearly 300 intersections that still need fixing. This long list of dangerous streets, outlined in the DOT’s own Vision Zero Pedestrian Safety Action Plans, represents an opportunity to save hundreds more lives. If Mayor de Blasio is re-elected, clearing this backlog of known-dangerous streets should be his first priority.

To help clear this backlog, the mayor recently increased the Department of Transportation’s budget by $1.6 billion. The problem is this: while the agency shows remarkable results at calming traffic and reducing crashes on any given street, it is moving at a snail’s pace to complete those projects. Now that his agency has the money, Mayor de Blasio must empower the DOT to deliver safety projects much more quickly and insist that it happens.

Today it takes a minimum of three years for the DOT to turn a dangerous highway-like city street into one that is designed for safe walking, cycling, and driving. Actually redesigning and repaving a street can happen in as little as a few months. Most of that three years is taken up walking on eggshells; the DOT attempts to anticipate and placate every parochial concern, as though safety infrastructure were a hot-button issue, and not a life-or-death public health concern. We’ve seen simple safety projects take years longer than they should, like the protected bike lane on 5th Avenue in Manhattan, which the community first requested in 2013, or get watered down to be less safe, like with Woodhaven Blvd., or get tied into petty power-brokering, like on 111th Street in Queens.

Before Vision Zero safety projects were proven life-savers, Mayor de Blasio could be forgiven for his timidity. Now, with the data strong and getting stronger (see Manhattan Institute’s recent report Vision Zero and Traffic Safety) it is time for the administration to elevate these projects to the urgent public health imperatives that they are. This means giving DOT freer reign to complete safety projects more quickly and break a few eggs, or rather break the hearts of a few petty power-brokers who care more about parking than people.

To further reduce preventable death on our streets, the mayor should also reconsider his opposition to congestion pricing.

More than just a way to fund transit and thin traffic so buses can move, congestion pricing is an effective safety tool. With fewer traffic jams, there can be more space for expanded safe pedestrian space and bike lanes. After congestion pricing was implemented in London, traffic crashes declined by 40%. A similar reduction in the proposed pricing zone in Manhattan would save dozens of lives per year.

And, as Mayor de Blasio doubles down on data-driven traffic-safety policies that work, he should cease those that do not. Every officer tasked with outfitting senior citizens’ canes with reflective tape or writing tickets to cyclists is one less officer assigned to rein in reckless drivers, who kill pedestrians hundreds of times more often than reckless cyclists do. (In fact, a cyclist has not killed a pedestrian since 2014.)

Targeting cyclists and pedestrians in the name of Vision Zero may placate some vocal complainers but it does nothing to make streets safer. In fact, evidence shows the opposite: the more walkers and bikers are harassed the less safe we all are -- bikers bike less, for example. It’s the opposite of the “safety in numbers” effect, well-documented by researchers, showing that the more people there are on the streets, the more motorists habitually exercise caution and care, even if they are a little bit annoyed. The only way to improve bicyclist and pedestrian behavior that has been proven to work is to build better, safer infrastructure.

Vision Zero is not “traffic safety as usual.” Rather, Vision Zero says that protecting human life is more important than preserving parking spaces or speeding drivers. It’s time for Mayor de Blasio to make this principle the rule, not the exception, and empower his agencies to manage traffic and deliver safety projects accordingly.

If Mayor de Blasio is re-elected, and launches his second term by doing what I’ve laid out here, he will save at least 100 more lives per year. He will be a hero. Nothing else that Mayor de Blasio did in his first term has gained him as much national recognition as Vision Zero, as dozens of cities are following in New York’s footsteps. It’s time for him to show the city, and the nation, the way forward again.

***

Paul Steely White is executive director of Transportation Alternatives. On Twitter @PSteely & @TransAlt.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Why is Governor Cuomo Returning Weinstein’s Money But Keeping Loeb’s?

Gov. Cuomo (photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Governor's Office)

New York’s political world was rocked recently by revelations that Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein, a major donor to Governor Andrew Cuomo and other top New York Democrats, had a long and sordid history of predatory sexual harassment -- and possibly sexual assault -- of women.

Initially Gov. Cuomo balked at giving back the $111,400 in contributions he had received from Weinstein. But a few days later, after Mayor Bill de Blasio called on all elected officials to return Weinstein’s money and the New York State Republican Party called out Cuomo, the governor saw the wiser route and decided to donate Weinstein’s tainted cash to a to-be-named women’s organization.

Sexism is deplorable and should not be tolerated, and it certainly should not play any role in our political system. Gov. Cuomo did the right thing by reversing course and shedding Weinstein’s money. It sends a strong message that he will not sanction Weinstein’s behavior, and it is a message to all political donors that sexism will not be tolerated.

However, we are confused. While Gov. Cuomo is sending a clear message that sexism is unacceptable, he has refused to send the same message about racism. Recently Daniel Loeb, a hedge fund manager and investor in privately-run charter schools who has given Cuomo $170,000, continued a pattern of behavior with an outrageously racist Facebook post. Loeb asserted that State Senate Democratic Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins, the highest ranking African-American female elected official in New York State history, had done “more damage to people of color than anyone who has ever donned a hood” -- an unmistakable reference comparing Stewart-Cousins to the Ku Klux Klan.

Loeb’s racism doesn’t stop there. In 2006 Loeb also called Prem Watsa, a Canadian corporate leader who is of Indian descent, a “shvartze,” a Yiddish term for African-American that equates to the n-word. Loeb has also sought to profit off of Puerto Rico’s debt and drive up prescription drug prices. And as board chair of Success Academy, he has supported excessively punitive and rigid disciplinary practices and suspensions meant to force struggling African-American and Latino students out of Success schools. Such zero tolerance behavioral policies have been shown to put students on track for the school-to-prison pipeline.

Despite Loeb’s documented history of racism and support of racist policies, Gov. Cuomo refuses to return campaign contributions from the wealthy financier. In contrast, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer immediately shed a $4,500 contribution he had received from Loeb once the recent Facebook post became public.

Regarding the Weinstein incident, Gov. Cuomo stated, "I have three daughters. I want to make sure that at the end of the day, this world is a safer, better world for my three daughters." We wholeheartedly agree with that, but African-Americans and other people of color have daughters and sons as well, and they merit protection from racists like Daniel Loeb, who clearly showed his belief that he is superior to Senator Stewart-Cousins and that he knows what is better for children of color than she does. In New York State we will not accept a double standard under which sexist political donors are treated as toxic in political circles, but money from racist political donors is condoned.

Sadly, we are living in a time when the president has made racism a mantra and has emboldened violent white supremacists to openly assault opponents of racism. We applaud Gov. Cuomo for making clear that Harvey Weinstein’s sexist money is unwelcome in New York politics. Gov. Cuomo’s hesitation to return Loeb’s tainted money is deeply concerning and offensive. We need him to forcefully and definitively repudiate Daniel Loeb’s racism. No more excuses, it is time for the governor to give back Loeb’s contributions, like he’s doing with Weinstein’s.

Gov. Cuomo recently described racism as “the greatest threat this country faces” - so there should be no problem treating racism with the same firm hand as sexism. If the governor decides to keep Loeb’s money, he is sanctioning racism, just as returning Weinstein’s money was a clear repudiation of sexism.

***

by Zakiyah Ansari and Carmen Perez. Ansari is advocacy director for the Alliance for Quality Education and Perez is executive director of Gathering for Justice and co-chair of the Women’s March.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Reinventing New York’s Iconic Canal System

Along the Erie Canal (photo: @NYSCanalCorp)

The Erie Canal just celebrated its 192nd birthday on Thursday, October 26, the date in 1825 when it was completed and Governor DeWitt Clinton, the canal’s most ardent and persistent advocate, boarded a packet boat in Buffalo for a 10-day journey to New York Harbor.

Upon arriving that day, Clinton emptied two casks of Lake Erie water into the harbor. This triumphant “wedding of the waters”—linking the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean—was followed by the overnight success of the Erie Canal. It transformed the nation by providing a pathway for westward expansion. It created new markets by dramatically cutting the cost and time to ship goods and allowed New York City to become a reigning center of world trade.

Suffice to say, times have changed along the Erie Canal, as they have along the Oswego, Champlain, and Cayuga-Seneca canals, the other components of the New York State Canal System. Mules pulling barges filled with lumber, coal, and hay, as the song goes, have long been gone. So are most of the barges.

Now, most of the traffic on the canal is either by recreational vessels or the bikers, hikers, joggers, and cross-country skiers who take 1.6 million trips annually on the Erie Canalway Trail, the old towpath used by the mules.

Nobody disputes the Erie Canal’s iconic status. But it is much more than just an historic artifact. This is an active, vital waterway. But when the New York Power Authority assumed control of the Canal System this year, Gov. Andrew Cuomo sensed it was a crown jewel in need of some additional luster.

That’s why he tasked the Power Authority and the state Canal Corporation to launch a global competition to reimagine the canal system, so it can be embraced by more visitors and once again serve as an engine of economic growth.

While boat traffic on the Canal System is well off its historic highs, its water still matters even if you never set foot inside a boat. It helps irrigate crops and golf courses in Western New York. Factories rely on the water for cooling systems for heavy machinery. It serves as a source of drinking water in Utica. And it’s the home for 27 hydroelectric plants—including three owned by NYPA—providing clean, renewable power.

It is on that foundation that this competition rests. We’ll seek entries on two tracks. The first will solicit proposals for infrastructure so we can reshape the relationship between the canals and the 226 communities they pass through. That could include building new facilities or re-engineering existing structures.

The second track focuses on the best ways to increase recreational use of the Canal System and enhance the visitor experience by creating a new tourist destination or giving a reboot to one that currently exists. There’s also a lot of potential in creating signature events, like the ones we held this year across the state to celebrate the bicentennial of the Erie Canal’s construction.

Under Gov. Cuomo, NYPA and the Canal Corporation will award up to $2.5 million for proposals that demonstrate the best ability to promote economic growth, increase visitation and are sustainable over the long term. The competition is open to anyone from anywhere -- good ideas have no boundaries.

Admittedly, I had never traveled on the Eric Canal before NYPA assumed control of the Canal System from the State Thruway Authority. Like most Manhattan residents, it’s something I had only heard of. The nearest canal was north of Albany. But I quickly realized why the canals are so integral toward defining the essential fabric of what made New York The Empire State.

Communities take deep pride in their link to the canals. It’s not just the dozens of museums and historical societies in the canal corridor that feel this way. Visitors constantly remark about the warm welcome they receive in canal towns because the locals like to show off their links to canals that turned the U.S. from mostly a nation of farmers to an industrial superpower. Many of these towns sprung up along the canal banks. They have plenty of great stories to tell.

We should be proud of that legacy. But with this competition, as New Yorkers we can be prouder of what is yet to come.

***

Gil Quiniones is president and CEO of the New York Power Authority. On Twitter @GQenergy & @NYPAenergy & @NYSCanalCorp.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York City: A Potential Source of Enlightenment in A Time of National Anxiety

Mayor de Blasio and the Statue of Liberty (photo: Ed Reed/Mayor's Office)

New York City is arguably the nation's most historically significant and diverse city. People across the nation look to New York for leadership, enlightenment, and inspiration, particularly in difficult times. Americans these days seem to be experiencing a sense of drift, puzzlement, uncertainty, divisiveness, and apprehension, in part due to the political situation in Washington, D.C.

There may be several ways New York programs and institutions can help.

A bully pulpit

Mayor Bill de Blasio has used his prominent position as mayor to speak out on some national issues such as immigration. He might use the high-visibility position even more expansively to provide a New York perspective on other political and cultural issues. He would be following a precedent set by former mayors.

For instance, former Mayor Michael Bloomberg, in a statement before the 9/11 Commission in 2003, eloquently described his city's cosmopolitan pre-eminence and why people look here for inspiration: "To people around the world, New York City embodies what makes this nation great. That's a function of our status as the world's financial capital, driven not only by Wall Street but our international prominence in such fields as broadcasting, the arts, entertainment and medicine....New York embraces the intellectual and religious freedom and cultural diversity that makes us truly the world's second home. We are a magnet for the talented and ambitious from every corner of the globe. In short, we embody the strengths of America's freedom."

Model blueprint for cultural enrichment and inclusiveness

On July 19 , the mayor and the city's Department of Cultural Affairs published CreateNYC: A Cultural Plan for all New Yorkers. "CreateNYC is the first-ever comprehensive cultural plan for the City of New York," says the introduction. "It is intended to serve as a roadmap to a more inclusive, equitable, and resilient cultural ecosystem, in which all residents have a stake."

It is a brilliant plan with many facets that can serve as a model for other cities. But New York City's history is apparently not addressed as a cultural asset. CreateNYC might expand its purview somewhat to include consideration of the city's historical heritage and how it relates to culture generally. Alternatively, there might be a separate report focused on history.

Guidelines for historical memorials in public spaces

On September 8, the mayor appointed an Advisory Commission on City Art, Monuments and Markers. It was in part a reaction to the tragic events in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August and other issues that led to heightened public awareness and sensitivity about public statutes and monuments. The commission is charged to "develop guidelines on how the city should address monuments seen as oppressive and inconsistent with the values of New York City." It will issue its recommendations by the end of the year.

In looking at specific monuments, the commission should consider the context and significance at the time they were erected. For instance, the Christopher Columbus statue in Columbus Circle was dedicated on Columbus Day, 1892, as part of a celebration of the 400th anniversary of his voyages that included parades, pageantry, and city-wide celebration. Speakers praised Columbus, but most of the emphasis was on New York's Italian-American heritage and the historical connections between Italy and the United States. Former Civil War general and historian James Grant Wilson, accepting the statute on behalf of the city and the state, told the assembled dedication crowd: "May it ever stand as a symbol of lasting friendship between Italy and the United States."

But the commission's work, including historical investigations, will not be simple. Columbus is a complex historical figure. A year before the dedication, in 1891, historian John Fiske's “The Discovery of America” was mostly positive about Columbus. But in the year of the dedication, 1892, historian Justin Winsor published “Christopher Columbus and How He Received and Imparted the Spirit of Discovery,” which disparaged the explorer.

The panel apparently is not charged with providing guidelines or criteria for what should be commemorated via monuments in public places. Its charge should be expanded to come up with such criteria which, in turn, could serve as a model for other cities.

Calling attention to real "New York values"

The Monuments and Markers Commission is charged with evaluating potentially offensive items against "the values of New York City." Last year, during the Republican presidential primaries, Texas Senator Ted Cruz spoke scornfully of then-candidate Donald Trump's alleged "New York values." This led to an assertive response from Mayor de Blasio and many others about what "New York values" really are, e.g., creativity, diversity, openness, inclusion, tolerance, and resilience. These exemplary values seem like ones the country needs to embrace more fully these days. The commission, or the mayor, might revive, expand, and deepen that discussion.

Education, historical understanding and civic consciousness

One of the best ways of building a capacity to understand and learn from history and develop interest in civic participation is through social studies in the schools. Here, New York City Department of Education guidelines and standards are particularly important, including the guidelines for grades K-8 and separate ones for grades 9-12. Other cities might review them for ideas on how to teach about historical awareness, cultural diversity, and citizens' civic responsibilities.

Guidance and inspiration from public history programs

Of course, New York City has some of the strongest public history programs in the nation. Historical programs and exhibits can help deepen historical perspective on current issues and controversies.

For instance, the Museum of the City of New York has an exhibit on "Activist New York.” According to the exhibit's description, "in a town renowned for its in-your-face persona, citizens have banded together on issues as diverse as civil rights, wages, sexual orientation, and religious freedom. Using artifacts, photographs, audio and visual presentations, as well as interactive components that seek to tell the story of activism in the five boroughs past and present, Activist New York presents the passions and conflicts that underlie the city's history of agitation."

New York is a model of diversity at a time when the concept is being questioned or even assailed in some places in this country. There are lots of historical programs that show New York's model leadership here. One is "Until Everyone Has It Made: Jackie Robinson's Legacy." On April 15, 1947 Jackie Robinson broke the professional baseball color line when the Brooklyn Dodgers started him at first base. "Featuring a wonderful array of archival materials, photography, programs, and memorabilia, the exhibition will tell a story that continues to resonate today," says the exhibit summary.

Getting young people aware of and interested in their city's history can help promote civic engagement as they grow into adult citizens. New-York Historical Society's Dimenna Children's History Museum is an outstanding resource for doing that.

***

Dr. Bruce W. Dearstyne lives in Guilderland, New York. He is the author of The Spirit of New York: Defining Events in the Empire State's History, published in 2015 by SUNY Press.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

In New Books on Bloomberg and de Blasio, Unreliable Atlantic Yards History

(photo: Spencer T Tucker via the Mayor's Office)

"Atlantic Yards down the memory hole" is a phrase I coined to describe how the facts and history of the controversial real estate project -- which was renamed Pacific Park Brooklyn in 2014 -- regularly get mangled by journalists, public officials, and commentators, often buffing away the controversy so that people may eventually wonder why anyone ever cared.

Part of that surely relates to the project's complex, twisting path, with at least 11 more towers yet unbuilt, joining the Barclays Center and four apartment buildings. It's tough to get right, even for me, and I write about Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park every day.

Also, the documentary record includes newspaper articles and government statements that either were initially flawed or no longer remain correct. Add the pressure of tight deadlines, with little time (or perhaps inclination) to check on, say, whether an old New York Times article was superseded by new information in the mainstream press, or corrected by a blog they don't read.

It's doubly dismaying, though, when book authors err, because they presumably have more time for research and because a hardcover presentation adds gravity. Unfortunately, interesting new books on the Bloomberg and de Blasio administrations get the Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park history wrong, in both small and significant ways.

It's understandable that the authors give Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park short shrift, as it's but one controversy within a complex set of governing challenges, and authors have to pick their spots. It doesn't ruin these substantial books. But it suggests they've not given careful attention to this project.

Only former Bloomberg Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff, in his Greater Than Ever: New York's Big Comeback, adds some new insights, but his triumphant narrative ignores some countervailing evidence.

***

Some authors make simple, though telling, mistakes, likely from sloppily surveying a clip file. Writes Chris McNickle, in Bloomberg: A Billionaire's Ambition, "Forest City Ratner, a national real estate firm, built the Barclays Center...on top of gritty MTA-owned railroad tracks." Put aside that Forest City Ratner was the New York arm of a national firm -- then Forest City Enterprises, now Forest City Realty Trust -- the arena was not built fully on (or over) the MTA's Vanderbilt Yard. The arena was built partly on the railyard. The tracks in the way were moved.

The other half of the arena footprint involved private (plus city/MTA) property and public streets. Had the arena site been limited to the railyard, Atlantic Yards wouldn't have sparked years of controversy and a battle over eminent domain to deliver some of that private property.

This error appeared frequently in the Times and other media outlets, and was only occasionally corrected. Probably the most egregious example was the enthusiastic appraisal of the original 2003 plan by Times architectural critic Herbert Muschamp, who wrote, "The six-block site...is now an open railyard."

Doctoroff similarly writes that Ratner "would build a huge development on the railyard at the convergence of the two major thoroughfares in Brooklyn -- Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues -- right next to the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Brooklyn's premier cultural institution." (Also, Brooklynites know that a huge mall and then the Williamsburgh Savings Bank building stand between the arena site and BAM.)

***

McNickle, to his credit, locates the Barclays Center "near Downtown Brooklyn." Doctoroff uses "Downtown Brooklyn" without the modifier, as do Joseph P. Viteritti, in his The Pragmatist: Bill de Blasio’s Quest to Save the Soul of New York, and Juan Gonzalez in his Reclaiming Gotham: Bill de Blasio and the Movement to End America's Tale of Two Cities.

The Times used that location a lot, but it also published a correction back in 2006 indicating that almost all the project site was in Prospect Heights. This might be seen as splitting hairs -- today, it could be argued that the Barclays Center extends the boundaries of Downtown Brooklyn, long seen as ending near the Williamsburgh Savings Bank, across Atlantic Avenue.

But the key issue is that the Atlantic Yards site was separate from Downtown Brooklyn, which New York City rezoned for high-rise buildings. After all, exiting from the back of the Barclays Center, you see Prospect Heights row houses across the street. Even Gregg Pasquarelli, the architect who redesigned the arena, called it "a big building in a residential neighborhood."

***

The overall amount of direct and indirect subsidies for Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park remains murky, in part because the project's not finished. But these books don't help.

"The city contributed $100 million in cash, infrastructure support, and tax abatements to the private project," writes McNickle, not specifying the value of the latter two categories. The New York City Independent Budget Office (IBO) estimated a package far more valuable than $100 million.

Writes Doctoroff: "When the financials of the deal deteriorated, the city and state upped our [cash] contributions to the project to $100 million apiece."

Actually, beyond that $100 million, the city later assigned $105 million to Atlantic Yards. Though city officials protested that a good chunk of that would have been delivered anyway -- and the IBO cautiously assessed a $150 million city total -- Forest City itself claimed it had secured $105 million more.

Why does that larger figure matter? Because the IBO, which in 2006 estimated that the arena would represent a net gain for city taxpayers, in 2009 projected a loss, based in part on new subsidy numbers. That goes unmentioned in Doctoroff's book, though the city, which embraced the earlier IBO assessment, attacked the later one. The overall impact remains inconclusive.

Beyond that, Doctoroff writes that, for the new Yankees and Mets stadiums, and the Brooklyn arena, "the city would fund only infrastructure costs, the stadium had to be financed by the team." Putting aside the controversial financing methods -- PILOTs, or payments in lieu of taxes -- that's not true regarding the Barclays Center.

The city's initial $100 million pledge could be used for infrastructure or for land purchases and, ultimately, it was used to buy arena land. In fact, Forest City's seemingly generous buyouts of condo owners -- prompting a front-page 2004 Daily News headline, "BONANZA," subtitled, "Brooklyn apt. owners offered $1 million-plus to make way for Nets arena" -- were funded by taxpayers, as I reported four years later.

***

"Because the project stood mostly over state controlled land," writes McNickle, "the city's normal review process did not apply." It's hard to fault him for conveying that typical explanation from public officials, though such state land is actually a plurality, not a majority.

Then again, some critics, including former City Planning Commissioner Ron Shiffman, long argued that the city could have negotiated with the Empire State Development Corporation, the state authority (since renamed Empire State Development) that wound up overseeing Atlantic Yards, to use the city's more substantial Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP).

Indeed, that's one mini-revelation from Doctoroff. "Although we would eventually become masters of ULURP," he writes, "at this point not a single rezoning had been approved and internally we had doubts about pulling off all we were trying to accomplish. Because the state owned much of the land, we decided that for expediency we would skirt ULURP and take advantage of the state's seemingly speedier process. With twenty-twenty hindsight, I am positive we could have placated our opponents in negotiations and gotten the process through ULURP."

He's got a point. The Bloomberg administration might not have placated all opponents -- many were opposed to the arena, period -- but likely would have made some concessions, leading to perhaps more legitimacy and more oversight for the project, as well as a voice for then-City Council Member Letitia James, who represented the area.

***

A more important revelation from Doctoroff is that, while he and the Bloomberg administration were public cheerleaders for Atlantic Yards -- “My role in this was to be as supportive and reassuring as possible,” he writes -- from the start in 2003 he questioned whether such a complex project would work.

Noting that developer Bruce Ratner had to buy the money-losing New Jersey Nets and navigate a complex set of approvals, Doctoroff “thought it was a crazy risk, but, hey, it was his money.” Actually, it involved public money too, as well as the opportunity cost of delaying alternative use for the public property at issue.

After all, given how much Atlantic Yards was sold to the public as providing solutions to the affordable housing crisis, didn't public officials owe us more candor about the risks of delay and nonperformance?

***

How long was Atlantic Yards supposed to take? That too goes down the memory hole. Viteritti writes that de Blasio "picked up the ball on real estate projects he inherited...he got Forest City Ratner, the developer of the massive Pacific Park Project...to accelerate the construction of 2,250 affordable apartments by 2025--ten years ahead of schedule."

To clarify: by 2014, there was a new developer: Greenland Forest City Partners, the joint venture owned 70% by Greenland USA, with Forest City the junior partner. That's worth noting, because community critics seeking a faster timetable tried to pressure the state before approval of that new majority owner was granted.

More importantly, "ten years ahead of schedule," while widely reported and not incorrect, is misleadingly incomplete. That timetable is ten years ahead of the previous schedule, which had been extended from ten years to 25 years.

So a 2025 completion date remains well behind the long-professed timetable. In fact -- and this was public knowledge before the author's deadline -- that target date is now in jeopardy, given that the developer last November paused market-rate development.

***

Doctoroff looks approvingly at Pacific Park so far, saying the arena opened "to (mostly) rave architectural reviews, with critics praising its proportions and its fit into the neighborhood." True, but critics' praise for the arena's innovative, elevator-based loading dock was followed by neighbors experiencing noisy truck lineups on residential streets.

The former deputy mayor also cites an increase in property values and busy restaurants, and none of the "feared terrible traffic congestion." The latter is true, but he should acknowledge that congestion fears were based on a project that had been built out faster, as well as far more fans driving from New Jersey.

Nor does Doctoroff acknowledge that impacts on the nearest residents can be brutal; one resident said she lives near "sh--show corner." He fails to mention that extravagant promises of local/minority/women hiring and contracting have never been confirmed.

"Thousands of units of desperately needed affordable housing are finally coming online," Doctoroff writes. The total is actually 781, in three towers, with new construction paused, and it's doubtful that all of the units are desperately needed.

After all, some 43% of the apartments built so far are aimed at middle-income households earning up to 165% of Area Median Income, far more than the income of the mostly low-income residents who marched enthusiastically for Atlantic Yards affordable housing. That translates, for example, into two-bedroom apartments costing well over $3,000 a month.

In fact, though the two already open buildings drew more than over 176,000 aspirants in the city's housing lottery, the developer was unable to fill all middle-income "affordable" units, presumably because of cost. So those apartments are now open to anyone who fits in the appropriate income category.

***

With affordable housing, the devil is in the details, though readers have no way of knowing from these books just how affordable the apartments are. Housing is called affordable if a household pays up to 30% of its income on rent.

The Atlantic Yards story deserves more nuanced attention generally. Gonzalez, in a few glancing mentions, does the best job of suggesting something was sketchy; Viteritti and McNickle acknowledge controversy.

Doctoroff claims success at a transformational project, scoffing at project opponents as brownstone owners wary of crowding, though he allows that we'll never know if Ratner makes money on the project.

What's missing, though, is a sense of the political skullduggery involved. For example, both books about de Blasio cite his relationship with the community group ACORN and its New York leader, Bertha Lewis. But neither mentions how, when the national group faced an internal embezzlement scandal and funders pulled away, Lewis (as ACORN founder Wade Rathke acknowledged) got her Atlantic Yards ally Forest City to deliver a loan and a grant, further cementing their relationship.

Also missing are issues of accountability, ones that will dog Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park during its next phases, inevitable twists, and likely requests for more government assistance. As the project's history is still being made, we should see its controversial past more clearly.

***

Norman Oder is a Brooklyn journalist who writes the daily blog Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park Report and is working on a book about the project. On Twitter @AYReport.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

On New York’s Amazon Wishlist? More Homegrown College Graduates

(via amazon.com)

Bids are due today for Amazon’s new headquarters and it seems cities across North America have joined the fray. The suitors are lining up with billion-dollar bouquets, and with good reason. What mayor could resist the promise of 50,000 well-paying jobs and all the economic energy that comes with the headquarters—a massive boost to the tax base, new cafes and food trucks, spin-off companies, and a legion of happy vendors? New York City alone has nearly two dozen neighborhoods vying for Bezos’ bounty.

Pundits have frequently written off the five boroughs as Amazon’s second home because of the exorbitant cost of living. Some are pointing to the subway meltdown. Yet an even greater obstacle may be the city’s underprepared workforce.

While New York has always been a beacon for titans of industry, striving immigrants, and the creative cognoscenti, for too long, the city has failed to develop enough local talent into the kind of smart, savvy employment base a modern company like Amazon demands. Just 36 percent of New York City residents have a bachelor’s degree or higher, according to the latest Census data, compared to 45 percent in Denver, 46 percent in Austin, and 55 percent in Washington, D.C. In Amazon’s current home base of Seattle, it is a whopping 59 percent.

New York’s ability to lure the world’s fourth largest corporation, or even its 40th or 400th, will hinge on whether its workforce is primed and ready. By that measure, the city has a long way to go.

More than 3.3 million city residents over age 25 lack an associate’s degree or higher level of college attainment. Residents with a bachelor’s degree or higher are largely concentrated in Manhattan, where the attainment rate stands at 62 percent, followed by just over 30 percent in Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island. In the Bronx, it is a distressing 18 percent.

Amazon should still see boundless potential on the Hudson. New York boasts a booming and entrepreneurial tech sector with more than 115,000 jobs today, an unparalleled smorgasbord of arts and culture, and the brand new Cornell Tech campus, alongside other world-renowned educational institutions.

But if New York succeeds in attracting Amazon, or any large company for that matter, whether GE, Aetna, or Tesla, it will be in spite of the city’s education and training systems, not because of them. New York can do so much more to ensure that its residents can access the opportunities that an Amazon would bring, while offering employers a much larger pool of homegrown talent.

Yes, New York is full of tech talent today. This is true, in part, because the city has become increasingly successful at attracting engineering and computer science graduates from Stanford, Carnegie Mellon, and other top universities around the world. But in an economy where technically skilled workers are prized—not just on Silicon Alley but in nearly every large and mid-sized company—demand is through the roof. New York needs a much bigger pipeline, not just for Amazon, but for blue chip companies and local start-ups alike.

Even if the vast majority of Amazon’s 50,000 new hires were imported from other places, New York would still be better off with them here than in Denver or Chicago or Atlanta. But no company—and certainly not a company with so many hiring needs—is going to make locational decisions that are completely dependent on bringing in outside talent. It is simply not realistic, or sustainable. Meanwhile, if half those workers or more were born, raised, and educated in New York, the benefits would be far broader—allaying the fears of those who see Amazon as more of an economic development trophy than an opportunity generator.

Such an achievement today would be almost impossible.

While New York City has done an increasingly impressive job of getting students through high school, it continues to struggle with college success, leaving students without the credentials an employer like Amazon demands. Today, fewer than half of all four-year college students at the City University of New York (CUNY) graduate with a degree in six years. Just 22 percent of CUNY’s community college students earn a degree in three years.

CUNY’s highly successful ASAP initiative, which provides supports to full-time community college students, and the CUNY Start program, which provides intensive preparation for students with remedial needs, are important steps in the right direction. But New York has a long way to go to achieve true college success for all.

Beyond the classroom, the city’s workforce development system still functions too much like a cumbersome placement agency. The de Blasio administration has laid out an impressive new vision with its Career Pathways initiative, aimed at developing career trajectories through skills building and education. But after more than three years, there is too little to show for it. The city needs to double down on proposed investments in bridge programs, career exploration, and on-the-job training, while strengthening and expanding partnerships with nonprofit providers, employers, and the public education system.

There’s no doubt that New York City is a formidable competitor in the quest for Amazon’s HQ2. No other city offers so expansive a world of culture and commerce in a single place, a paragon of urbanism and urbanity animated by an astonishingly diverse population. But if Amazon heads elsewhere, policymakers should not just blame cost and congestion. They should look to the serious shortcomings in the city’s human capital development system, which remains far from meeting its full potential.

***

Matt A.V. Chaban is the policy director and Fisher Fellow at the Center for an Urban Future. On Twitter @MC_NYC and @nycfuture.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

As We Close Rikers, Setting Our Sights on Essential State-Level Reforms

Gov. Cuomo at an update prison (Governor's Office)

Anyone following New York City politics knows about JustLeadershipUSA’s mission to close the jails at Rikers Island. In less than a year, the #CLOSErikers campaign successfully pressured Mayor Bill de Blasio to commit to shuttering the jail complex. It is no longer a question of if Rikers will close, but when. But the campaign has always known that closing Rikers would require reforms at the state level as well. An overhaul of our statewide bail, speedy trial, and discovery statutes is necessary to reduce the population at Rikers so that it can finally and expeditiously close its doors.

Even if Rikers were closed tomorrow, these reforms would still be necessary. While New York City has successfully reduced its jail population over the past few years, county jail populations across the state are growing. Today, 63% of people held in jail in New York State are held in jails outside New York City. Of those 25,000 husbands, fathers, brothers, sisters, children, and loved ones who are sitting in jails across our state, 70% have not been convicted but remain unjustifiably caged while they await the outcome of their cases.

This reality is a consequence of punitive and discriminatory criminal justice policies that have decimated communities, primarily poor communities and communities of color, for decades.

To end this human rights crisis, we need bold action from Governor Andrew Cuomo and our state Legislature. That is why JustLeadershipUSA launched #FREEnewyork, a campaign focused on empowering those who have been most harmed by our jails and prisons to hold Governor Cuomo and our elected leaders in Albany accountable and unapologetically demand real solutions to these self-inflicted problems.

Governor Cuomo said that Rikers should be closed in three years. Now he must deliver around the state he leads. He and his colleagues in Albany have both the power and the responsibility to drive us toward that Rikers goal while also addressing the failings of our statewide criminal justice system.

They can start with overhauling our broken bail system. We need reform that eliminates money bail, protects the presumption of innocence and the right to freedom, limits when and how any pretrial conditions are instituted, and prohibits biased risk assessment tools. Bail reform must focus on ending the devastating repercussions that even initial involvement with the criminal justice system can have on people, especially on low-income families who too often must choose between paying bills or paying for their loved one’s freedom. People who can afford bail achieve better outcomes in their cases, and everyone deserves access to these outcomes.

Albany must also enact comprehensive statewide speedy trial and discovery reform. Today, no other state in the country comes close to matching the appalling unfairness of New York’s readiness rule approach to ‘protecting’ one’s right to a fair and expedient process.

We need a true speedy trial law that sets concrete limits on when a defendant must actually be brought to trial. As it stands now, prosecutors can cause unforeseeable and unending delays in the trial process without significant repercussions. Combined with the current state of our bail laws, this leads to human beings trapped in cages while they await their hearing before a judge or jury.

What is already a bad situation is only made worse by New York’s current discovery laws, which are widely regarded as some of the most regressive in the country. We need a new discovery law that requires open, early, automatic, and mandatory discovery, guaranteeing defendants and their lawyers access to vital information about their cases. Without this, defendants and their attorneys have little to no access to information about the charges they face.

These reforms are vital for New Yorkers most affected by mass incarceration, and countless studies have shown that criminal justice reforms like these increase public safety, improve relations between communities and law enforcement, and create better outcomes for victims and taxpayers. Yet, while each of these reforms and each of their respective components are important, none are sufficient on their own if we truly want to end the plague of mass incarceration that grips New York State. Comprehensive, connected reforms are necessary for the real, lasting, and positive change in our criminal justice system that New Yorkers deserve.

Without this action at the state level, New York will continue to commit human rights abuses on a daily basis. The atrocities of our criminal justice system will linger, and New Yorkers will suffer unimaginable harm as a result. To fight for reform, close Rikers, and decarcerate county jails throughout New York State, directly impacted individuals and communities across the state must raise their voice, and, together, bring a simple message to Governor Cuomo and our legislators in Albany: we are watching you, we demand real and bold reform, and the time to act is now.

***

Glenn E. Martin is founder and President of JustLeadershipUSA. On Twitter @GlennEMartin and @JustLeadersUSA.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.