Hope in the State Senate

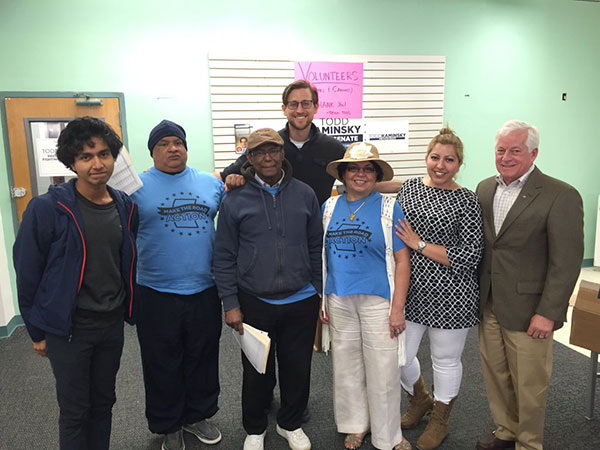

Make the Road Action volunteers for Todd Kaminsky

Last Tuesday, many New Yorkers were focused on the presidential primaries, but there was another election that may be even more important for communities like mine. In a special election for State Senate in Nassau County, Democrat Todd Kaminsky won a seat long-held by former Republican Sen. Dean Skelos.

This result was key for three reasons.

First, it showed the importance of the votes of Latinos, immigrants, and people of color outside of New York City.

As a black Latino immigrant living on Long Island, I’ve seen first-hand how the region has changed in recent years away from being the overwhelmingly white suburban area it was once. Now, as reported by Newsday, it is likely that communities of color were the key difference in the victory of Todd Kaminsky by a relatively small margin, demonstrating the growth of our community on Long Island and our power. While we still have much work to do to continue registering and mobilizing voters, last Tuesday’s result shows that we are becoming more aware about the importance of voting in local and state elections, which often have more direct impact on our lives than federal contests. Communities of color—particularly Latino and immigrant communities—are growing in population and so too is our political weight.

Second, this choice will be important in addressing one of the main barriers blocking progress for our communities: the state Senate.

Many of the abuses suffered by our community in New York stem from state laws that fail to protect us. in many cases, we are even targeted. These laws—weak rent regulations, lack of police and criminal justice reforms, restrictions on accessing financial aid, and more—exist because for years we have had no one in the Senate from Long Island who represents us at the time of decision-making. Make the Road Action, of which I am a member, backed Todd Kaminsky because he committed to supporting our community—for example, by raising wages, expanding healthcare access, and ensuring higher education access. Meanwhile, the Republican campaign mailed anti-immigrant propaganda to excite ultra-conservative voters with a message akin to Donald Trump’s.

We will continue to fight on priority issues for our community—to pass the DREAM Act, strengthen rent laws, pass criminal justice reform, and more—and we are confident that Senator Kaminsky will be there with us.

Third, Senator Kaminsky's victory could be the first step in changing the balance of power in Albany.

Through November, Republicans are likely to maintain control of the Senate through an alliance with the Independent Democrats (IDC). But this special election showed that progressive candidates themselves are able to succeed against conservatives on Long Island—the first time we’ve seen that in years—and we expect to have several close state Senate elections in our region in November. With only one or two more wins, Democrats could take control of the state Senate, which would give us the opportunity to pass new laws that protect workers, young people who want to study, tenants, LGBTQ immigrants—in short, our entire community.

This election showed the growing power of our community. Now we must continue to build our strength and ensure that we are prepared to fight for our rights and vote in November, when the entire state Legislature is up for election.

***

Frank Sprouse-Guzman is a member of Make the Road Action and a Bay Shore resident. On Twitter: @MaketheRoadAct.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Time to Cut the High Cost of the Free Plastic Bag

A rally for the plastic bag fee bill (photo via @bradlander)

It’s a fact: people who live in America’s most polluted environments are most commonly people of color and poor. New York City is no exception; thanks to decades of unfair policies, over 75 percent of the city’s entire solid waste stream is now processed in a handful of low-income neighborhoods and communities of color in the outer boroughs. Consequently, these communities bear the disproportionate burden of high truck traffic, diesel fuel emissions, unsanitary conditions, and noise pollution.

Spearheaded by communities of color living in environmentally overburdened areas, the Environmental Justice Movement emerged to collectively protect the places where we live, work, and play. Now, we’re voicing our support, from Brooklyn to the Bronx, for legislation to drastically reduce the number of plastic bags in our waste stream by attaching a 5 cent charge.

What do “free” plastic bags have to do with environmental justice? The bag that many of us were given today is just one of 9.37 billion plastic bags that make their way into the city’s waste stream every year – assuming it doesn’t end up polluting our waterways. A whopping 91,000 tons of plastic bags are hauled on diesel trucks for processing at transfer facilities clustered in industrial waterfront neighborhoods, including North Brooklyn, Sunset Park, and the South Bronx. Our communities, more than all others in New York, suffer the noxious fumes and noise pollution, the traffic congestion and unsafe streets, the high rates of asthma and respiratory problems, and the general neighborhood blight caused in part by our city’s love affair with this icon of disposable convenience.

Faced daily with these burdens, low-income New Yorkers of color already know the high cost of “free” plastic bags.

The legislation pending before the City Council, Intro. 209, is an integral part of the city’s larger zero waste goal to divert 90 percent of our waste stream from landfills by 2030. Meeting this ambitious target would improve quality of life for thousands of New Yorkers living in environmental justice communities near waste facilities. The City Council worked alongside advocates to draft a bill that addresses the concerns of low-income New Yorkers.

The bill provides exemptions for customers using SNAP, WIC benefits, and other transactions at emergency food providers. It also includes provisions for community outreach and the distribution of free reusable bags in low-income communities.

Grassroots, community-based environmental justice advocates have a long history of finding innovative solutions to proactively address the inequitable environmental burdens that we face. Int. 209 is not a cure-all for our solid waste problems – we have a long way to go to achieve a truly equitable solid waste system. But a law on the books showing the city working to meet its waste reduction goal is no doubt a big step in the right direction. By reducing the amount of single-use bags in our communities, the city can help lessen the burden of unnecessary waste and trucks in our environment, and improve the neighborhoods of low-income communities and communities of color.

***

Eddie Bautista is the executive director of the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance, where Priya Mulgaonkar serves as policy organizer. Mark Winston Griffith is the executive director of the Brooklyn Movement Center, a community organizing body in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Crown Heights and the surrounding area.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

James Takes Softer Stance on Atlantic Yards

James (at podium) & Cumbo (in green) at Barclays Center (photo: Azi Paybarah)

When Public Advocate Letitia (Tish) James served as City Council Member for the 35th District in Brooklyn, from 2003 through 2013, she was a vocal, high-profile opponent of the Atlantic Yards megaproject, as reflected in the 2011 documentary Battle for Brooklyn.

James was a plaintiff in two lawsuits challenging the willingness of government authorities to relax deals with developer Forest City Ratner, and promoted another lawsuit filed by Brooklynites who went through a coveted pre-apprenticeship training program, run by a Forest City community partner, but didn't get expected union cards and jobs.

In her successful 2013 campaign for citywide office, James even criticized mayoral candidate Bill de Blasio, generally an ally, regarding his support for the project, which includes the Barclays Center and 16 towers (of which four are now rising), set to house 6,430 apartments, of which 2,250 are "affordable."

Since becoming public advocate, James, understandably, has paid far less attention to the project, which in 2014 was renamed Pacific Park Brooklyn after Chinese developer Greenland Holdings bought a majority stake, excepting the arena and one tower. James also joined local officials calling for the 2016 Democratic National Convention to come to the Barclays Center.

Still, it was surprising to learn, from New York Daily News Sports I-Team reporter Michael O'Keeffe, the main contributor to a four-part series on Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park that began April 11, that James would talk up the project at the behest of a developer she's long criticized.

As O'Keeffe told it, at about 43 minutes into a podcast, published April 22, in which we both appeared, months earlier, as he began looking into Atlantic Yards,, he reached out to James, but was eventually told she didn't want to comment.

As his publication date approached, and after the developer likely knew there was critical coverage coming about issues like sexual harassment by construction workers, low pay for arena staff, and neighborhood disturbances, O'Keeffe "got a call out of the blue" from James.

While James told him she's not in touch with the grassroots, she said, as O'Keeffe put it, that "she doesn't really hear a lot of complaints from residents, what she hears is a lot of excitement about the possibility of affordable housing."

O'Keeffe asked her if the developer - whose local face remains Forest City Ratner - asked her to call, and she said yes.

James apparently did not know the specifics of O’Keeffe’s coverage, such as the harassment by construction workers and arena attendees toward a 23-year-old African-American woman. (James is the first woman of color to hold citywide office in New York.)

On the podcast, I speculated that James was thinking about a 2021 mayoral run, as Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park criticism has less weight, and friendly relations with powerful developers can be helpful.

But her posture - perhaps a lapse or poor political judgment - still seems strange. (She declined comment, in response to my queries.) Had James looked on my blog or sources like Atlantic Yards Watch or Instagram (see the #bciza tag), problems faced by arena neighbors have been amply documented.

It's precisely her responsibility, as Public Advocate, to serve as a watchdog over the city agencies that have failed to curb, say, illegal parking or construction activities that spill out blocks from the project.

While James understandably supports "affordable housing," the devil's in the details. James was critical of some of that housing, for example, challenging the developer regarding the percentage of family-sized units, lower than promised, in the first tower under construction, the lottery for which just opened up.

She did appear at the December 2012 groundbreaking for that tower but was not quoted in any press release, and has stayed out of December 2014 and June 2015 press releases saluting two "100% affordable" towers. In other words, she had until recently kept her distance.

Beyond a focus on her next campaign, perhaps James has been influenced by Michelle de la Uz of the Fifth Avenue Committee, a Brooklyn nonprofit, who was de Blasio's nominee to the City Planning Commission, and remains James' representative.

De la Uz in 2014 helped negotiate a new timetable to deliver the 2,250 Atlantic Yards affordable housing units by 2025 rather than 2035. (That's faster than the previously extended timetable, of 2035, but a ten-year buildout had been touted when the project went through approvals in 2006 and then 2009.)

That was progress, but de la Uz downplayed the fact that two "100% affordable" towers that came out of that deal skewed toward middle-income households earning six figures and were less affordable - in terms of incomes served - than the developer long pledged. De la Uz and allies in the BrooklynSpeaks coalition had actually once criticized that original configuration as not affordable enough.

Today, de la Uz and allies likely have James' ear more than those bearing the brunt of Atlantic Yards impacts. But the Daily News series, as well as my coverage of a public meeting in mid-April, detailed continued frustration from neighborhood residents, as the harassment victim pointed out how state officials, in a report to an Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park advisory board, had downplayed the harassment. The developer did say it would roll out a color-coded ID system to make it easier to recognize construction workers.

Similar political calculations may be at play for James's successor on the Council, Laurie Cumbo, who in the wake of the Daily News series was curiously silent. After all, Cumbo chairs the Council's Committee on Women’s Issues and has regularly spoken out about issues of sexual violence, including those affecting women and girls in Nigeria.

During her Council campaign, Cumbo did criticize Atlantic Yards, but soon adopted a wishy-washy posture; she's regularly praised the below-market housing without reference to its actual affordability. Had a less powerful constituent than the Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park developer been connected to the harassment, I have to think Cumbo would have been less cautious.

Though Cumbo did not respond to an April 18 request for comment, after she was informed that this article was in the works, she sent a statement Wednesday that, among other things, cited her work on women’s issues, including “legislation that will raise awareness to prevent sexual harassment and assault.” She noted that venues in the district had brought more traffic and thus quality of life issues, and that in recent weeks there has been “greater visibility on the need to address sexual harassment within our community.” She said that New Yorkers face “cat calls, lewd gestures, inappropriate language and unwarranted comments about the physical characteristics of their bodies” and that “in the City of New York, these acts will not be tolerated."

Her statement, interestingly enough, didn’t acknowledge the victim but indicated respect for the developer. “I want to acknowledge Ashley Cotton, SVP of External Affairs, Forest City Ratner Companies for working with the NYPD, Barclays Center, contractors, and unions to implement several measures including a color-coded identification system for its workers to improve accountability and a guest code of conduct for Islanders games to enhance public safety,” Cumbo wrote. “These preliminary steps are indicative of our collective commitment to fostering a safe environment for women, the LGBTQ community, and countless others who deserve to freely commute.”

Fewer than 90 minutes later, Cumbo circulated to her mailing list an announcement about the application process for 461 Dean, the first Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park affordable housing tower.

***

Brooklyn journalist Norman Oder writes the watchdog blog Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park Report.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

For More Progress in Homeless Services, Continue to Consult the Experts

Homelessness policy announcement (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

On April 11, the de Blasio administration announced the results of its 90-day review of homeless services. The review’s inclusive and collaborative process is impressive. The city consulted numerous stakeholders, including two groups too often ignored: clients, specifically homeless individuals in shelters and on the streets; and nonprofit homeless service providers. With respect to clients, the city surveyed 630 individuals in homeless shelters and conducted focus groups with over 80 Coalition for the Homeless, VOCAL-NY, Picture the Homeless, and Urban Justice Center Safety Net Project clients. Sixty nonprofit providers were also engaged in the review process.

As the city implements the 46 reforms in its review, it should continue including and collaborating with clients and providers. It would be a grave error to continue the mistakes of the past where clients’ concerns about shelters and providers’ requests for capital repairs were ignored.

The first opportunity for inclusion and collaboration is the Interagency Homelessness Accountability Council (or the Interagency Coordinating Council in City Administrative Code § 21-307). Both nonprofit service providers and currently/formerly homeless individuals should serve on the Council.

The vehicle is already in place: the Homeless Services Advisory Board set forth in City Administrative Code § 21-306 - as City Council General Welfare Chair Stephen Levin noted during the April 21 hearing, “Oversight: An Examination of the Department of Homeless Services 90-day Review.”

To better understand why the city should listen to providers, look to the Mayor’s Supportive Housing Taskforce, where supportive housing providers alerted the city to the unfeasible scattered-site supportive housing rates before it rolls out the first 500 units of a new program this year.

In addition, the city would do well to include and consult more formerly homeless individuals as it provides homeless services. This enables the city to utilize those with direct experience and also addresses the review’s Reform #25: Promote career pathways for shelter residents.

One area to include consumers is the Department of Homeless Services (DHS) Office of the Client Ombudsman. The city can also employ formerly homeless individuals as homeless outreach workers and continue to utilize peer specialists as DHS case managers. The mental health field recognizes the invaluable role of peers and so should homeless services.

Another opportunity for client inclusion and collaboration is around the review’s Reform #12: Increase safety in shelters through a NYPD management review and retraining program. As the NYPD re-trains DHS security staff, it should utilize training akin to the Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training that NYPD officers receive to de-escalate situations involving persons in emotional distress. Whereas that training draws on the experiences of individuals with mental health challenges, this can also draw on the experiences of homeless individuals.

As the city continues to work to improve its homeless services, there are no better people to seek guidance from than those now or recently involved in related programming on a daily basis.

***

Nicole Bramstedt is the Director of Policy at Urban Pathways, a nonprofit social services and supportive housing organization serving homeless adults. On Twitter at @UrbanPathwaysNY.

Flushing’s Affordable Housing at Risk

Last week, the New York City Council approved the contested East New York rezoning - the first of 15 proposed neighborhood rezonings through which Mayor de Blasio intends to advance his goal of preserving 120,000 units of affordable housing and producing 80,000 new units at below-market rents. Described by some as a rezoning taking place “under the radar,” the Department of City Planning (DCP) has been conducting a planning study and holding numerous community town halls on a ten-block area of Queens dubbed “Flushing West.”

This proposed rezoning would have a transformative impact on Flushing, a densely populated, pan-Asian immigrant neighborhood with a sizable Latino population and a small but historic African-American community. Although DCP recently postponed the April certification of the Flushing West rezoning plan (which would have initiated the uniform land use review procedure (ULURP), the plan continues to move forward and remains a key piece of the mayor’s controversial housing program.

As the rezoning of Flushing West moves forward, the existing affordable housing stock there is at risk.

After much public debate and protest, Mayor de Blasio’s mandatory inclusionary housing (MIH) plan was approved by the New York City Council in March. MIH is a citywide policy that requires residential developers in newly upzoned areas to provide some below market-rate housing, either inside a new development or somewhere off site. As MIH (and the related Zoning for Quality and Affordability (ZQA) plan) moved through ULURP, communities contested the plan on numerous grounds: it would not build enough affordable housing; the affordable housing that would be built would be too expensive for those most in need; increased density would exacerbate transportation, education, and infrastructure problems; large new buildings would alter local streetscapes; and, most importantly, the plan would spur luxury development and hasten gentrification.

Relative to the vigorous and sustained public debate on these issues, there has been little public discussion on the ways that the city’s proposed rezonings are already impacting New York City’s largest form of affordable housing: rent regulation through rent control and rent stabilization.

Rent regulation accounts for nearly all of Flushing’s affordable housing. The neighborhood’s white-hot real estate market, however, increasingly threatens these rent-stabilized apartments. DCP’s proposed rezoning - which links the production of affordable housing with the construction of thousands of luxury units - has only increased land speculation and, therefore, landlords’ imperative to deregulate their holdings. Though the rezoning has been paired with an increase in funding for anti-eviction legal services, it has already catalyzed a number of hyper-speculative real estate transactions in downtown Flushing, including within the rezoning area.

Based on the 2014 state Division of Housing and Community Renewal (DHCR) list of rent-regulated buildings, there are 388 rent-stabilized buildings in Flushing. This list, however, includes buildings that have partially converted to co-ops, meaning some units are owned by residents. Conversion of rental buildings to cooperatives requires a minimum of 15 percent of tenants opting to purchase their apartments. DHCR lists properties as rent stabilized as long as there is at least one rent-stabilized unit in the building.

Based on a review of city Department of Finance sales data, 81 buildings, including five that converted to cooperative in the past year or so, recorded 1,198 apartment sales since 2010. In addition to the hundreds of co-op sales in rent-stabilized buildings, 42 buildings (with a combined total of 1,800 rent-stabilized apartments) were also sold during the study period of 2010 to January 2016. The sold buildings represent a sizable 11 percent of all of Flushing’s rent-stabilized buildings.

In December 2015, a massive sale of eight rent-stabilized buildings, all but one located a few blocks from Flushing’s waterfront, was covered by Crain’s New York Business. These rent-stabilized buildings, comprising 488 apartments, are clustered on Flushing’s Sanford Avenue and were sold to an investor group represented by New Jersey-based Treetop Development LLC. ACORE, a California-based investment fund established in May 2015 - only a few months before the Sanford Avenue purchases - financed the hefty $138.8 million purchase. ACORE is capitalized by a $1.6 billion commitment from Delphi Financial Group Inc., a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Tokio Marine Group, Japan’s largest publicly traded insurer. The purchase of seven Sanford Avenue rent-stabilized buildings, financed by transnational private equity investors, illustrates how multi-family, rental properties in the outer boroughs are treated as global investment vehicles with tremendous potential profits.

In order for those profits to be realized, however, rents will have to increase substantially, and in all likelihood, the apartments will be deregulated. Although Treetop Development LLC principal Adam Mermelstein reassured, “We’re not running after tenants like some landlords do, trying to induce turnover on the apartments to get them to market rate,” their $10 million investment in “an intensive capital expenditures program” portends displacement. Treetop Development LLC plans to renovate apartments and landscape gardens in order to “remake the Flushing Portfolio into one of the premier residential addresses in Flushing, Queens.” This rebranding language underscores that so-called “major capital improvements” in rent-stabilized buildings are a primary landlord strategy to permanently raise rents and facilitate tenant turnover.

This speculative activity is not confined to privately-owned buildings. Queens College students learned from a local resident that tenants were recently evicted from 132-30 Sanford Avenue. This building is listed on two real estate websites as for sale, with one site noting that the building is currently under contract. Further research indicated the building is owned by one of Asian Americans for Equality (AAFE)’s tax-exempt organizations - Community Homes Housing Development Fund Company Inc. According to the building’s deed, AAFE purchased the building in 2008 for $3.5 million. Online realtor descriptions highlight the gap in current and potential rent revenues as a key selling point: “The average monthly rent is $1,023 month, approx. 76% of the current market value, offering tremendous upside potential.” The building is now selling for $9.8 million - a 180 percent increase in just eight years.

In October 2015, DCP completed a Draft Scope of Work for an Environmental Impact Statement, which identified 13 projected development sites and included a breakdown of anticipated outcomes based on the proposed upzoning. On these 13 sites, DCP expects the production of 2,062 residential units (excluding 1,254 units of luxury housing currently under construction at Sky View Parc) of which 516 would be affordable to households earning 60 percent of AMI ($54,360 annual income for a family of four) or 619 units affordable to households earning 80 percent AMI ($69,040 annual income for a family of four).

DCP’s Draft Scope of Work was completed before the City Council added the option of 20 percent of units affordable at 40 percent AMI, which would mean the Flushing West rezoning may result in 412 units affordable to a family of four with an annual income of $36,240. The Flushing Rezoning Community Alliance, a coalition of nonprofits, unions, and churches, fought hard for this option because the median household income for downtown Flushing residents is just $34,428. The final Flushing plan may also include additional HPD subsidies toward deeper affordability, but the extent, quantity, and longevity of those subsidies is yet to be determined.

With Flushing’s remaining rent-regulated apartments at stake, it is important to look at the balance of what is being offered now: the proposed rezoning will produce thousands of market-rate, luxury housing units; a mere 412 apartments will be affordable to average Flushing residents (and then only if the local City Council member and developers choose the newly added option); and nothing at all will be built for families making below-median wages.

The neighborhood’s wholesale transformation, which has already begun in expectation of an upzoning, would sweep rent-regulated housing up in its wake and trigger even more harassment, rent hikes, and evictions than the neighborhood has already seen. This scenario demonstrates that Mayor de Blasio’s MIH program is less about preserving neighborhood affordability than turning working-class spaces into luxury enclaves, with small pockets for the middle class.

In Flushing’s overheated real estate market, where even nonprofits enrich themselves by selling rent-stabilized buildings for enormous profits, this planned rezoning is already adding fuel to fires of gentrification and displacement. The addition of a few hundred units of affordable housing could not possibly stem the transformative effects of global finance and commercial real estate speculation, and the preservation program the city is currently pursuing will do little to protect rent-regulated apartments.

City planners must stop acting as if the negative consequences of upzonings on rent-regulated housing will be mitigated by the paltry provision of new quasi-affordable units, or by increased investments in legal services (though the latter are, of course, important). Instead, we need to prioritize the preservation of rent-stabilized apartments and the production of truly affordable housing, decoupled from market-rate development and its attendant impacts on neighborhood land markets.

***

Tarry Hum is a Professor at the City University of New York and author of Making a Global Immigrant Neighborhood: Brooklyn's Sunset Park.

Samuel Stein is a PhD student in Geography at the Graduate Center, City University of New York.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Unfinished Business: Governor’s Higher Ed Budget Leaves Trail of Uncertainty

Cuomo & SUNY 2020 (photo via The Governor's Office on flickr)

In the height of political chaos across the country, New Yorkers have much to be proud of: our state recently increased the minimum wage and signed paid family leave into law in this year's budget, major contributions toward shared prosperity for all. This is certainly in large part because of Governor Cuomo’s strong leadership.

However, this year’s higher education budget is a mixed bag for New Yorkers, leaving many unfinished items on the table and a trail of uncertainty for years to come.

Governor Cuomo has positioned himself as a hero, the leader who saved our state from political gridlock and dysfunction and delivered for New York families and students. But let’s set the record straight - after the governor introduced his proposed budget in January, it was our students who organized and fought back and our Legislature that held the line against the governor’s unnecessarily austere higher education budget.

We should all celebrate the victories we achieved this budget cycle. Among them are a one-year tuition freeze at SUNY and CUNY, which comes after five years of annual $300 tuition hikes. We also achieved an increase in funding for the state’s educational opportunity programs and for full-time students at our community colleges. Advocates also successfully blocked Governor Cuomo’s planned $485 million state disinvestment to CUNY -- a third of the operating budgets for CUNY’s senior colleges.

Yet, when it comes to ensuring that New York puts higher education access and quality first, these successes are incremental at best.

The state has used tuition dollars to fill funding gaps by raising tuition, thereby shifting the cost to New York families for years. This is part of the governor’s SUNY 2020 Rational Tuition Policy, scheduling annual tuition hikes of $300, totaling $1,500 over five years, which expires at the end of this academic year. How a $1,500 increase could be considered “rational” policy is beyond comprehension.

Furthermore, it’s concerning that the FY 2017 budget did not provide the roughly $100 million to SUNY and CUNY that would have come from continued tuition increases, which after years of disinvestment further starves the universities and threatens their ability to ensure quality, affordable education for New York students.

A one-year freeze should be the first step to rolling back these hikes and strengthening state investment in public higher education.

All of this has taken place as the state’s Tuition Assistance Program (TAP), the key tool to help families pay for college, remains grossly out of date. In fact, the governor’s pervasive funding cuts have created a shortfall for the first time in the program’s 40-year history. What’s worse, the program currently requires that, when a student qualifies for it, SUNY and CUNY must use their operating budget to make up the funding difference between the maximum TAP award and tuition, taking away resources to provide other support services.

This also leaves hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers to fill on their own the gaps that TAP used to cover. Currently, the maximum TAP award is stuck at $5,165 while tuition at CUNY is $6,330 and at SUNY is $6,470, creating a gap of more than $1,100 depending on where you go. This is estimated to cost CUNY $50 million in the next year alone.

The state needs to increase and index the maximum TAP award with tuition and make the structural changes necessary to ensure true access for all New York students. This includes opening TAP up to part-time and undocumented students.

Another broken promise is New York’s funding commitment made through the SUNY 2020 plan, which required the state to provide SUNY and CUNY baseline funding levels that would also cover mandatory cost increases, also known as Maintenance of Effort (MOE). Late last year, Governor Cuomo vetoed a MOE bill, which passed through the Legislature with bipartisan support, saying it’s a budget issue. The governor neglected to include it in this year’s executive budget, and it wasn’t included in the final budget deal either, continuing to cost the universities money that could go to lowering tuition, restoring classes cut in tough budget times, and providing support services to students.

The state’s budget deal also comes at the immediate expense of the CUNY faculty, members of which haven’t had a pay raise or contract in nearly six years, threatening CUNY’s ability to attract and keep the talent necessary to provide a competitive and high-quality education in a 21st century economy. Funding for a final contract deal should be reached before the state legislative session ends in June.

With New York’s $147 billion budget and GDP of $1.4 trillion – as much as the country of Spain – our state higher education system should be leading the nation. And it certainly shouldn’t disguise disinvestment as short-term freezes and temporary fixes, particularly when it comes to quality, affordable postsecondary opportunities.

How the governor and the state Legislature address the unfinished business outlined above over the course of this session, and the session following the November elections, will be the true test of how our leaders and lawmakers value access and opportunity at the people’s university.

***

Kevin Stump is Northeast Director of Young Invincibles. YI sits on the Steering Committee of the CUNY Rising Alliance.

OnTwitter @KevinStump and @YoungInvincible.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Could a Doorman Have Saved Akai Gurley’s Life?

A NYCHA building entrance (photo via NYCHA on flickr)

Protests recently broke out in response to the sentencing of former police officer Peter Liang to five years of community service for the killing of Akai Gurley. Officer Liang’s criminal behavior in a stairwell in Brooklyn’s Pink Houses might have been less professional than some of his more experienced peers, but he was hardly an extreme outlier. He wasn’t even the first officer to shoot a totally innocent person by mistake during a vertical patrol. In 1994, thirteen-year-old Nicholas Heyward Jr. was killed by police on the roof of his building in Brooklyn’s Gowanus Houses while playing with friends on the roof. The officer claimed he was startled by Hayward when he opened the door to the roof.

In order to really reduce the chances of these kinds of violent encounters we are going to have to make changes that go far beyond incarcerating one or two officers or changing the way training is conducted. One way to start would be for the City to take broad responsibility for the social and physical conditions that led to this tragic encounter.

The problems in Pink Houses and many other public housing complexes run much deeper than one poorly trained rookie police officer. There has been widespread acknowledgement that the physical upkeep of the building played a role in Gurley’s death. The only reason Gurley was using the stairs was because the elevators weren’t working properly. There was also a lack of decent lighting that at the very least played an indirect role in this tragedy because it produced a climate of fear that contributed to Liang’s decision to patrol with his finger on the trigger.

As I pointed out recently in the New York Times, the City needs to stop using the Broken Windows theory to justify aggressive and invasive over-policing of communities of color and instead fix some actual broken windows. For too long when communities complain about not feeling safe, the City’s only response is to send in more armed police. These communities don’t need more criminalization, they need real services to improve the quality of their lives.

In July of 2014, Mayor de Blasio announced the creation of the Mayor’s Action Plan for Neighborhood Safety, in response to an uptick in crime in public housing. The plan called for providing much needed maintenance funds to NYCHA as well as some improvements in security technology such as better locks, security cameras, and exterior lighting. There was also a small amount of money for some short term funding for summer youth programs. But, the centerpiece of the program was assigning 700 more police to public housing.

Why hasn’t the City instead used some of the millions of dollars it has spent on increasing the number of police and enhancing security technology to hire doormen for these buildings? Yes, doormen.

One of the major factors contributing to insecurity in public housing is lack of adequate control over building entry. People routinely hold the doors open for others or buzz in people they don’t know. Even more shocking is the routine way in which the locking mechanisms and intercom systems simply aren’t working. A doorman working on the building would be able to control entry and monitor conditions in a building’s lobby and other public spaces.

With doormen, there would be a major reduction of exactly the kinds of low-level quality-of-life concerns that motivate the vast majority of resident complaints such as trash, noise, broken lights, people hanging out in the lobby, and non-working elevators. Right away there would be a huge drop in the number of arrests for trespassing, something the NYPD has been heavily criticized for in the past. Over and over again people tell stories of being erroneously arrested or ticketed for trespassing while legitimately visiting a friend or relative. In a number of cases people who actually live in the building have been subjected to this treatment.

If these buildings had doormen, there wouldn’t be a need for vertical patrols by the police and the dangerous encounters that go along with these patrols.

A doorman policy would also dramatically reduce the numerous arrests and summonses police give out in public housing buildings for a host of minor violations that could be avoided by having someone in charge of “keeping the peace.” In cases where the police are called, the doorman would be able to assist them by pointing out those that belong in the building and those that don’t. A doorman would also quickly learn about suspicious activity such as constant late-night visitors to a particular apartment that might indicate drug dealing or other problematic activities.

Putting in professional doormen would cost the Housing Authority money. But it might also save the city a significant amount of money. Right now the city spends hundreds of millions of dollar on armed Housing Bureau police. A system could be put in place where we incrementally shift resources from policing to civilian doormen in an effort to find a better balance between providing aggressive policing and much needed civilian services.

Some may say that government shouldn’t be providing amenities to poor people that many middle and working class families can’t afford. This is an understandable argument given the exploding cost of living for many. But the reality is that when crime and disorder go unchecked in public housing we all end up paying the price in the form increased expenditures for police, jails, and emergency rooms. Public Housing should be a model of housing for poor and working class New Yorkers, not another burden for those already struggling.

***

Alex S. Vitale is associate professor of sociology at Brooklyn College and author of City of Disorder: How the Quality of Life Campaign Transformed New York Politics. He is on Twitter @avitale.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Adversarial Justice Court

Back in the early 1990s, there was a bar association forum devoted to the nascent and growing problem-solving court movement. After I raised some questions about the “we’re all in this together” premise of the courts, one of the advocates pointedly asked me, “Do you really believe that the adversarial Criminal Court is working?” “I couldn’t say,” I replied. “I’ve yet to see an adversarial court.” That remains the case today.

Even though the nation’s Criminal Courts since their inception have been described as assembly lines processing defendants through quick and dirty guilty pleas, there were few efforts at meaningful reform until the 1990s and the problem-solving court movement. What started with the development of a few local community courts soon expanded to a dizzying array of specialty courts and the problem-solving court industrial complex. Presently, across the country there are more than 4,000 community courts, domestic violence courts, fathering courts, youth courts, drug courts, mental health courts, sex offense courts, driving while intoxicated courts, human trafficking courts, and more.

New York State has long been at the problem-solving court vanguard and is home to an unprecedented 141 drug courts and just the other day unveiled a new Veterans’ Court. And yet, as each new boutique court sprouts up, one court remains noticeably absent – an adversarial justice court where police behavior is scrutinized and the prosecution is mandated to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

Supporters of problem-solving courts maintain that the courts grew out of the futility and revolving door nature of the Criminal Court and a desire to deal with the causes that brought the accused to the courthouse. The idea is to use the occasion of arrest as a way into addressing, if not solving, defendants’ problems. Owing to the scant historical attention paid to poverty, substandard housing, unemployment, and the cumulative impact of institutional racism, many defendants do have a host of problems. Yet rather than try and confront decades of neglect and devise a meaningful social safety net, those in control began to see the Criminal Court as the repository for all these problems. Ironically, the present reality of scarce resources for serious problems may well have created a place for problem-solving courts.

Although the Criminal Court often does cycle the same people in and out of its doors, that is hardly its only, or most serious, deficiency. Over 30 years ago, a scathing report from the New York City Bar Association pointed to the lack of hearings and trials and questioned whether the Criminal Court was even appropriately called a “court.”

As problem-solving courts now dot the judicial landscape the number of hearings and trials has actually decreased. As one commentator put it, by focusing on early intervention and treatment, problem-solving courts fast forward to sentence, jumping over, if not ignoring, the constitutionality of the arrest or questions of guilt or innocence. As even the Supreme Court acknowledged recently, American criminal justice is a system of guilty pleas.

The lack of adversarial testing of the charges is not just an academic concern. Every study of the consumer perspective – the accused’s point of view – has found that the defendants’ greatest objection to the process is the lack of their day in court; that they had no opportunity to be heard or to question their accusers. This is for many defendants the very problem they would like the court to solve. In fact, scholars argue that defendants afforded their full measure of due process are less likely to recidivate, even if ultimately convicted, because they believe they were treated seriously rather than just rushed through a guilty plea.

Almost fifty years ago the Supreme Court in Terry v. Ohio recognized the importance of judicial oversight and emphasized the need for trial courts to “retain their traditional responsibility to guard against police conduct which is overbearing or harassing, or which trenches upon personal security without the objective evidentiary justification which the Constitution requires.”

Much-admired federal Judge Jack Weinstein of the Eastern District of New York has written about the “vital function” trial courts must play to police the police. Indeed, it was the Criminal Courts’ abdication of its critical oversight role that led to the Floyd v. New York stop-and-frisk lawsuit in federal court.

An Adversarial Justice Court could hear every case charging a possessory offense that is based solely on police observations and testimony and hold mandatory pretrial suppression hearings to determine the legality of the arrest. Given the ongoing controversy surrounding marijuana arrests, and the recent questions raised about the burgeoning number of “gravity knife” charges, these types of possessory offenses demand public hearings.

Similarly, while the Mayor’s Office and the NYPD are championing a new “gun court” aimed at doling out appropriate punishment, those charges inevitably raise constitutional search and seizure issues that merit adversarial litigation with the police officer testifying under oath and subject to cross-examination about what he did and why he did it.

An Adversarial Justice Court would benefit police officers as well as the accused.

At present, you could be a police officer for years and never once be called to testify. The court-appointed monitor in the Floyd case wrote in his report to the judge earlier this year that police officers were still struggling to understand the sum total of factors that provided reasonable suspicion to stop and frisk. Testifying in court and thereafter having a judge rule on the legality of their actions would better enable police officers to learn what amalgam of facts allows them to stop, question, frisk.

In addition to ordering reform of policies, training, and supervision, the judge in Floyd also recognized the need for ongoing monitoring of police stop-and-frisk behavior. She emphasized that those people and communities most affected by stop-and-frisk should play a central role in the remedial process. What better way to involve the public, and to thereby make the police accountable, than by holding public hearings with officers testifying about their search and seizure activity? The resulting transparency could go a long way in efforts to instill public confidence in the police in the post-stop-and-frisk era.

And if the sky didn’t fall and litigated hearings proved successful, the Adversarial Justice Court might one day even resurrect jury trials, and our case-processing machinery could be fully transformed into a court. Now that would solve a lot of criminal justice problems.

***

Steven Zeidman is a professor of law at CUNY School of Law. He is on Twitter @SteveZeidman.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Earth Day Commitments to Our Drinking Water

Minnewaska State Park (photo via @nystateparks)

Most New Yorkers take their drinking water for granted. We think of contaminated drinking water as a problem that happens to other people in other parts of the world. However, the recent crises in Flint, Michigan and Hoosick Falls, New York forced us to realize that these problems can also crop up close to home. As we continue to celebrate Earth Day, let us take a few minutes to reflect on the current situation and consider some of the threats to our drinking water right here at home, as well as what we can do about them.

Flint has become the poster child for the kind of devastation drinking water contamination can wreak on a community. Thousands of children in Flint have been exposed to dangerous levels of lead, and their water is still not safe to drink. This problem is not just happening in Flint, but also Binghamton, New York and likely many more communities across the country that still have lead pipes in place.

Since the time of Roman aqueducts, water infrastructure has been a hallmark of advanced civilization. Yet we have let our public drinking water systems crumble in neglect. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) now estimates that communities face a $384 billion backlog to repair drinking water infrastructure across the country.

Unfortunately, there are also many other threats to consider. While our aging infrastructure has been getting the most attention recently, there are many other dangers to our drinking water, which range from toxic chemicals to Superfund sites to factory farms.

While Flint may well be the worst example, it is not the only time reckless disregard for our drinking water has had lasting impacts on public health. In late 2015, the EPA urged residents of Hoosick Falls, a village of 3,500 people about 30 miles northeast of the State Capitol in Albany, not to drink or cook with the tap water. This is because testing of the village's water detected levels of the chemical PFOA that made the water unfit for human consumption. This toxic chemical has been linked to an increased risk for cancer, thyroid disease, and serious complications during pregnancy.

A federal class-action lawsuit has been filed against Saint-Goblin Performance Plastics and Honeywell International, which both operated manufacturing plants that are a focus of the contamination. The toxic chemical is associated with the making of Teflon, which was used in products manufactured at the plants.

Across the nation, concern over various types of water contamination has risen. In recent years, officials have documented more than 1,000 cases of oil and gas drilling operations contaminating local water. Agricultural pollution is threatening drinking water in places like Ohio, where runoff from agribusiness operations contributed to a toxic algae bloom in Lake Erie, which contaminated the drinking water for 500,000 people around Toledo with cyanotoxins in 2014.

We believe all New Yorkers deserve safe drinking water. We know what it will take to achieve this vision.

First, we need to restore the public infrastructure that brings water to our taps. Second, as the incident in Hoosick Falls shows, we also must protect the rivers, streams, and aquifers from which we draw our water. And finally, the public must have the right to know about water pollution – with robust monitoring of our waterways, regular testing from our taps, and standards that truly protect public health.

On each of these fronts, we are making progress, but much more work lies ahead. The crisis unfolding in Flint has finally put water infrastructure on Congress’ radar. In addition to ongoing negotiations to immediately aid Flint itself, New York Rep. Paul Tonko has now introduced bills to triple funding of the safe drinking water state revolving fund. In the past, the program has enjoyed broad bipartisan support. Congress must overcome the current mood of partisan rancor and give communities the resources they need to get the lead out.

For protecting our sources of drinking water, EPA took a landmark step last year in restoring protections of the Clean Water Act to streams, which help provide drinking water to 117 million Americans, including 11 million in New York. But these protections are currently tied up in the courts, while also facing another round of attacks from polluters and their allies in Congress this spring, so we’ll need our representatives to stand up and continue to fight for clean water protections.

We are also seeing small steps to enhance our right to know when our water is at risk. Just two months ago, the House overwhelmingly passed a bipartisan bill to strengthen EPA’s duty to notify the public when lead is putting drinking water at risk. Other proposals are being considered to require testing for lead in both drinking water and in children’s blood levels.

To build on this progress it will take political will. So on this Earth Day, let us vow to keep drinking water on the forefront of our minds even long after stories of Flint have left the front pages of our papers.

***

Heather Leibowitz, Esq. is the Director of Environment New York, a statewide environmental advocacy group. On Twitter @EnvNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Earth Day Expectations for Mayor De Blasio

photo: Ed Reed/Mayor's Office

The foundation of our city is strong neighborhoods. We’re unified by common values and impacted by similar trends, from the affordability crisis to a changing climate. But each part of the city is its own living, breathing organism with a unique history, and its own set of needs.

Mayor de Blasio has visionary goals to create a stronger, more just city neighborhood by neighborhood, but he also knows these goals won’t come easy or cheap. As the mayor gears up to release his first progress report on his ambitious blueprint to reduce our city’s carbon emissions, here are five things he can do right now that will go a long way toward sustainability and livability:

Cut commute times for New Yorkers with the longest journeys to work. As a candidate, Mayor de Blasio promised 20 new select bus service routes by 2017. So far we have achieved nine, and of those six were operational by the time he took office. In parts of the outer boroughs, transit deserts make commuting via public transportation a huge challenge. A robust SBS network will take cars off the road and improve quality of life for transit-starved New Yorkers.

Ensure that every New Yorker can walk to a well-maintained neighborhood park. Local parks are an essential part of the fabric of our community. Not only do they boost resiliency, but they improve public health by encouraging people to get outside for recreation. Increasing the parks budget from 0.5 percent of city’s overall budget to its historic funding level of 1 percent would mean capital projects get done sooner, and that we have the necessary workers to maintain these spaces.

Expand access to healthy produce in low-income neighborhoods. New York creates a bounty of fresh produce from apples to potatoes to yogurt. The problem is, many of these fresh, local foods do not make it to low-income neighborhoods. An expansion of the NYC Green Carts initiative would help small farmers stay in business, reduce emissions from transporting food, and create healthier communities.

Make green installation easier for homeowners. Permits and regulations for green technologies can be complex and overwhelming. A one-stop-shop permitting process within the Department of Buildings should handle all alternative energy applications: solar thermal, solar photovoltaic, or geothermal and green infrastructure such as green roofs or other water retention design.

Reduce single-use throw-away litter. The carry-out bag legislation being considered by the City Council can make a significant difference in reducing consumption and consequently litter from single-use bags. Getting them out of the environment means fewer clogged storm drains and polluted waterways, and cleaner streets and parks.

Goalposts such as reducing emissions 80 percent by 2050 or getting to zero waste to landfills by 2030 can seem daunting because they’re so big and so far away. The only way to reach these goals is to break them down into incremental milestones. These are five things the city can do right now. They don’t need to be studied and they’re not reliant on technologies that haven’t reached scalability.

New York City is the place of the possible. If we engage and empower New Yorkers to pitch in and work together toward our common goals, we know we can stay on the right track to take them from vision to reality.

***

Marcia Bystryn is president of The New York League of Conservation Voters. On Twitter: @nylcv.