An Election Year Budget

It was the same scene: reporters scrunched into rows of blue plastic folding chairs chaotically checking their BlackBerrys; the chiefs of the city government's largest departments lining the front row; and the mayor -- charcoal power suit, red tie -- delivering a particularly morose PowerPoint, presenting a practically apocalyptic view of the city's budget.

Let the 2010 budget season begin.

On Friday, Mayor Michael Bloomberg released his preliminary budget for fiscal year 2010, which starts July 1. With the economic meltdown showing no sign of stopping, the mayor proposed to slash almost $1 billion from city spending and raise the city's sales tax to create $900 million in revenue. He has threatened to chop the city's work force by about 8 percent -- including 14,000 teachers -- if funding from Albany does not materialize or municipal employee unions do not compromise on health benefits.

Though most city officials say the country's dire straits call for serious measures, they also recognize that 2009 is an election year. Election years breed political compromises. Not only will city officials hear from advocates and constituents protesting the cuts, they also will hear from their political opponents. Inevitably, decisions made in June affect the election's outcome in November.

Forget the 2010 budget cycle. Say hello to the '09 campaign season.

The Budget Breakdown

In 2005, after several years of gloomy budget scenarios, the mayor was upbeat -- he called his preliminary budget then "cautiously optimistic."

Translation: Things had improved since the downturn following September 11th, and Bloomberg was looking for another four years as the fiscal guardian of one of the biggest budgets in the country.

Fast forward four years and we see the same mayor seeking another term in office (albeit unexpectedly). This time around, with the economy in disarray, Bloomberg's forecast is less confident.

"I am as optimistic as I can possibly be for the longer term," the mayor said, reiterating that the city would not return to the 1970s when core services were slashed due to an economic downturn.

"I think we'll be able to do it together," the mayor added. "We have the seasoned leadership and the public support."

The city faces a yawning $4 billion budget gap due to a decline in tax revenues, attributed to the financial crisis on Wall Street. To address these fiscal woes, the mayor proposed a $58.8 billion budget -- a decrease from the projected 2009 budget of $60.1 billion. The city's deficit, the mayor reminded reporters Friday, could have been as much as $6 billion if the City Council and mayor had not acted to cut spending and increase property taxes late last year.

Essential to the mayor's proposal is funding from both the federal and state governments -- funding that is far from guaranteed. Lobbing the problem a few hours north, the mayor urged the State Legislature to rescind a proposed $770 million cut to education aid for the city or see close to 14,000 layoffs at the Department of Education, most likely teachers (with attrition that number is 15,630). The mayor said aid the state receives from Washington's economic stimulus package could right Albany's wrong. (See related story on state budget cuts.)

"I am sympathetic with the state," the mayor said, referring to the projected $15.4 billion deficit in Albany. "Here is a chance for Albany to pay for their fair share of education with someone else's money. If there was ever a case for us to put pressure on them, it's now."

The mayor plans on filling the budget gap through $1 billion in aid from the federal government for Medicaid, almost $1 billion in agency spending cuts and about $1 billion from the restoration of state cuts and renegotiating health care benefits for union workers. He also is considering increasing the sales tax to 8.625 percent from 8.375 percent in addition to repealing the exemption for clothing and starting to tax items, like haircuts that previously were tax-free.

Bloomberg said a sales tax increase is not definite since the economic climate is still settling and revenues could change between now and when the budget must be approved in June.

Overall, unless the city gets help from unions and the state, the municipal workforce could decline by nearly 23,000, Bloomberg said, through both layoffs and attrition.

Under the mayor's doomsday proposal, the majority of layoffs are slated for education, but other departments would not be immune: the Administration for Children's Services could see 608 layoffs, Homeless Services 222, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene 57 and the Finance Department 17. The mayor proposed losing 7,686 positions through attrition from multiple agencies, including a reduction of 1,000 uniformed police officers.

The Teachers Take Their Toll

Just in time for the Superbowl, the mayor punted.

The most drastic of cuts, specifically the Department of Education layoffs, which comprise 80 percent of the total proposed workforce reduction, are because of Albany, the mayor said.

That sparked this reaction from United Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten: "The union has pledged, and indeed has been working together with the mayor on the federal recovery and on ensuring we get a fair share from Albany. But making virtually all our first, second and third-year teachers pawns in this political battle is callous and unfair to them and their students. Worse, in blaming Albany, the city itself masks the magnitude of its own cuts.”

Weingarten is not alone in thinking the mayor is pegging Albany for the city's problems.

Baruch College Professor Doug Muzzio said the mayor's budget was overflowing with "wishing and hoping." If the federal and state funds he is expecting do not come through, then his re-election prospects could suffer.

"If you lay off 15,000 teachers, man, that’s going to resonate," Muzzio said. "It's going to resonate loudly, through bull horns."

Whether it's political maneuvering or financial strategy, other officials and political observers think the mayor has a point. At the end of the day, they say, teachers will not be sacrificed.

"It would not be acceptable to lose 15,000 teachers, period," said Councilmember David Yassky, who also is a candidate for city comptroller. "The mayor is absolutely right that it's up to Albany to keep our school funding constant. What he is trying to highlight there is that the governor's budget would reduce our school aid quite dramatically."

Already Unpopular Cuts

As for spending in general, Bloomberg recognized some departments were harder hit in this preliminary budget than others.

"It would be fair to say everybody takes the same hit, but the real world is you have to keep the streets safe, and the real world is you have to have a certain amount of guards for each prisoner," Bloomberg warned.

Of all the agency cuts, social services have been slashed the most -- by about 8.2 percent. Youth programs, libraries, cultural affairs, CUNY, transportation, and health and mental hygiene all have cuts around 7 percent. The Administration for Children's Services, which is slated for significant layoffs in comparison to some agencies, has seen a 6 percent cut.

The police, fire, correction and sanitation departments all received cuts of between 2 and 3 percent.

But how will these reductions, if approved by the City Council come June, affect the average New Yorker?

The Sanitation Department will reevaluate trash routes (and their frequency) so workers will pick up more tonnage. The city is doing away with pickups of grass clippings. After-school programs, including summer youth programs, will be cut significantly.

Bloomberg proposed to eliminate dual company firehouses by taking away either an engine or a ladder in certain stations. He also proposed to eliminate a firefighter position on 64 engines, bringing down the count to four (It will be done through attrition and it excludes lieutenants on the scene).

He wants to increase rates for single rate parking meters from 50 cents to 75 cents an hour, stop the city's nutrition counseling for those with HIV, increase admission fees at the Central Park Zoo and the Queens and Prospect Park wildlife centers and cut funding to senior centers.

Proposals floated to increase revenue include an increase in CUNY tuition by $200 a semester and a 5-cent tax on plastic bags, both of which would require approval by the state government.

All of these proposals, particularly the cuts to social services, could provide ammunition for challengers come November.

"I think it's shortsighted by Mayor Bloomberg to propose these cuts in terms of managing the city's budget and in terms of managing his political future," said Sean Barry, the director of the NYC Aids Housing Network. "We don’t want to return to the time where New York City is warehousing homeless people with AIDS in welfare hotels."

Politics or Policy

Bloomberg didn't have the last word on Friday.

Not to be outdone, one of the mayor's political rivals, Comptroller William Thompson, came out with his own proposal immediately following the address: upping the city's personal income tax on those earning more than $500,000.

When Gotham Gazette asked for more details about the comptroller's suggestion, a spokesman said Thompson was reviewing a number of ideas and would release details once finished.

Already some advocates and council members see an income tax increase as a better option than a hike in the sales tax, which they call "regressive," since it will have a disproportionate effect on lower-income people.

"Sales tax are regressive," said Jennifer March-Joly, executive director of Citizens' Committee for Children of New York. "You raise revenue that way, that’s clear, but the problem is for those that need to shop and make far less money. It's much more burdensome than the income tax."

With sides taken and criticism thrown, revenue options may be the first concrete mayoral campaign issue in 2009.

"The mayor’s plan would balance the budget on the backs of working people," read a statement from Thompson released following the mayor's budget address. "The mayor’s budget proposal relies far too heavily on a sales tax increase at a time when the city’s hardworking families and small businesses are suffering."

The mayor said he had not put an income tax increase on the table, because he anticipated the state would increase it to solve its own fiscal woes. (See related story.)

Tackling A Base

A critical element in the mayor's budget plan is tapping city unions to pay 10 percent of their health insurance premiums. According to the Independent Budget Office, 90 percent of city employees enrolled in its insurance program do not premiums.

Brave, maybe. But political observers say it could be tough to cross unions in an election year.

"The mayor is now in a position, regardless of re-election issues he is going to have, to make the unions his partners or his election will be more problematic," said a source close to the unions in New York City. "If he gets re-elected he will have real war."

Obviously, Bloomberg does not rely on the city's unions for financial support for his campaigns, as many politicians without billions of dollars do. In a citywide election, though, union support is key.

So far, the reaction to his proposal has been icy.

In response, Lillian Roberts, the executive director of city's largest municipal employees union, District Council 37, released the following statement: "Union members should not be asked to shoulder the bulk of this burden. Workers did not create this fiscal crisis and cutting into their hard earned benefits should not be viewed as the quick fix that will solve it."

Others scoffed at how realistic this proposal would be: "Be serious here, Mr. Mayor," quipped Muzzio.

The mayor has previously been criticized for not doing more to rein in rising pension and benefit costs, often thought of as "uncontrollable." Some, including political consultant Joseph Mercurio, say now is as good a time as any to negotiate union contracts. According to the mayor's office, payments to retirees for pensions and health benefits will increase from $11.7 billion in 2007 to $16.8 billion in 2015.

An analysis last year by the Independent Budget Office projected about $400 million in savings could be garnered during the first year of city employees paying 10 percent of their premiums.

The Political Hurdles

Councilmember John Liu, a candidate for public advocate, recognizes a tough budget year can mean tough politics.

"It stinks to run for election in a very difficult time," said Liu.

Though officials interviewed by Gotham Gazette say politics will not enter into their decisions on the budget, their policy choices could certainly affect the election.

"Politics plays a role in everything," said Councilmember Letitia James, who is running for re-election to her seat in Brooklyn.

Bloomberg extended term limits and launched his third term candidacy because he said he was needed to lead the city through tough times. That said, the outcome of this year's budget could dramatically influence whom the electorate (which still favors Bloomberg) chooses this November.

Most politicians, even those who themselves are seeking higher office (like Yassky, Liu or David Weprin), contend politics will not come into play this budget cycle.

"It's fiscal reality," said Councilmember David Weprin, the council's finance committee chair and a candidate for comptroller. "I think you need somebody in the comptroller's office that is going to recognize the fiscal situation and deal with it."

Yassky, agreed. "You first decide what's the right policy and then you go and make your case to voters and they can understand it."

Arguably the most eternal optimist is the alleged non-politician, the mayor himself.

"I hope and I expect that the fact that it's an election year will not enter into it at all, because (the council doesn't) have any choice, nor do I," the mayor said Friday. "We have to address these issues, and I would argue the public wants these issues addressed and wants you to make the tough decisions. My advice to anyone in government is do what you think is right and in the long term it will work out."

Can Obama Help Save New York?

As Barack Obama takes office today, many New Yorkers have high hopes that change has come -- and it will be change for the better. Much of that hope springs from excitement surrounding the first African American president ever and the first one in decades with urban connections. And in this overwhelmingly Democratic city, where Obama beat Republican John McCain by a four-to-one margin, there is a palpable hunger for new ideas and attitudes.

Like most Americans, New Yorkers want action too -- particularly on the economy. The recession has hit New York, the home of Wall Street, hard, with rising unemployment, job losses and slowdowns in all types of businesses. As a result, the state faces a $15 billion deficit over the next 15 months and the latest projections show the city government, thought to be on firmer ground, peering into a $4.3 billion abyss.

City and state leaders, along with fiscal experts and ordinary New Yorkers, hope Obama can help. At his State of the City last week, Mayor Michael Bloomberg rolled off a number of initiatives that called for some federal dollars, including a proposal to revamp the city's air traffic control system and a pilot program that offers jobs to struggling students if they stay in school. (For more on the mayor's State of the City, see A Recovery Package From Bloomberg.)

Highest on the city's wish list may be federal dollars for infrastructure. "Our cities have to be a central focus of any recovery plan," Bloomberg said recently. Any federal funding should first go to our urban environments, Bloomberg added, especially for bridges, roads, trains and tunnels.

Other New Yorkers have their own ideas. Here several experts offer their views about the proposed economic stimulus package and what the new administration can do to help lift New York -- and the nation -- out of the economic crisis.

Paying Attention to Cities By Jonathan Bowles

After years of federal policies neglecting urban areas, Barack Obama has sent some encouraging signals that he understands their importance. Certainly, New York could use a helping hand. The director of the Center for the Urban Future lays out some ideas for what the president could do to aid New York.

An $825 Billion First Step By James Parrott

The stimulus package proposed by Congress is key to halting the economy's downward spiral but it will not solve all our problems. Economist James Parrott of the Fiscal Policy Institute looks at what the package would do -- and what more needs to be done.

Using the Crisis to Prevent the Next One By J. Mijin Cha

The current turmoil can help us reduce our dependence on Wall Street and create good "green collar" jobs that help fuel a resurgence of the middle class. The director of campaign research at the Urban Agenda explains how.

Infrastructure Investments that Make Sense By Carter Craft

As big as the stimulus package may be, the country has to invest the money wisely. An urban planner offers some novel ideas for New York projects -- from recycling grease to ferries for freight.

From Gas-Guzzling Cars to Clean Buses By Charles Stone

Simply lending funds to struggling auto companies won't spur economic growth. Instead, an economist suggests, the government should create a voucher program to deploy the resources of the auto companies, spur investment -- and help the environment.

Previous Articles

A Federal Stimulus for City Parks By Anne Schwartz

Advocates hope that President Obama and Congress will recognize that funding parks would not only improve the quality of life and the environment but also spur investment and raise real estate values.

Stimulus Money: The Downturn's Silver Lining? By Graham Beck

The stimulus package could offer more federal funds for transportation projects. The MTA is making its list, but there are sure to be lots of restrictions -- and competition

Using This Crisis to Prevent the Next One

Photo (c) Urban Agenda

While the economic picture is grim across the country, New York City has been especially hard hit in recent months. The city's heavy dependence on Wall Street revenues has left us facing a projected budget shortfall of nearly $4 billion. Adding to the city's crisis, a quarter of the shortfall is due to state cuts resulting from Albany's crippling financial difficulties.

For More on Helping New York's Economy

Paying Attention to Cities By Jonathan Bowles

After years of federal policies neglecting urban areas, Barack Obama has sent some encouraging signals that he understands their importance. Certainly, New York could use a helping hand. The director of the Center for an Urban Future lays out some ideas for what the president could do to aid New York.

An $825 Billion First Step By James Parrott

The stimulus package proposed by Congress is key to halting the economy's downward spiral but it will not solve all our problems. Economist James Parrott of the Fiscal Policy Institute looks at what the package would do -- and what more needs to be done.

Infrastructure Investments that Make Sense By Carter Craft

As big as the stimulus package may be, the country has to invest the money wisely. An urban planner offers some novel ideas for New York projects -- from recycling grease to ferries for freight.

From Gas-Guzzling Cars to Clean Buses By Charles Stone

Simply lending funds to struggling auto companies won't spur economic growth. Instead, an economist suggests, the government should create a voucher program to deploy the resources of the auto companies, spur investment -- and help the environment.

Previous Articles

A Federal Stimulus for City Parks By Anne Schwartz

Advocates hope that President Obama and Congress will recognize that funding parks would not only improve the quality of life and the environment but also spur investment and raise real estate values.

Stimulus Money: The Downturn's Silver Lining? By Graham Beck

The stimulus package could offer more federal funds for transportation projects. The MTA is making its list, but there are sure to be lots of restrictions -- and competition.

The crisis highlights the danger of the city's economic over-reliance on Wall Street. Even when times are good, only a few New Yorkers reap economic windfalls. When times are bad, the entire city suffers.

For all the pain it is causing, though, the sagging economy presents us with the chance to rebuild our economy in a way that prevents similar economic crises in the future. The federal economic stimulus package before Congress presents an opportunity to build a greener and more equitable economy. Urban Agenda, convener of the New York City Apollo Alliance, urges Congress to fund projects that will create high-quality, "green collar" jobs and help make New York City more environmentally sustainable.

A stimulus package for New York City must focus on increasing investments in public infrastructure -- rehabilitating and retrofitting schools, buildings and mass transit systems - not on giving tax breaks. Currently, the Obama administration is proposing $150 billion in tax cuts for businesses. However, prominent economists, including an advisor to Republican presidential candidate John McCain, note that every dollar spent on public infrastructure projects generates $1.50 in economic activity, while tax breaks lack this "multiplier effect." Every $1 in tax cuts produces less than $1-- and sometimes as little as 30 cents -- of economic activity.

Green Is Not Enough

While we need to act quickly, we must also act responsibly. It is not enough to just create "green" jobs. Instead, we must create "green collar" jobs that pay well, provide health benefits and offer opportunities for career advancement while improving our environment.

This is key. Creating jobs that pay poorly and do not provide health benefits or pathways out of poverty will lead to an underclass of workers employed in green jobs but unable to make their way into the middle class. If we consider both environmental benefits and wage and job standards, we can have jobs that will help the resurgence of the middle class, strengthen our economy and make New York City a leader in sustainability.

The NYC Apollo Alliance has compiled a list of recommendations for evaluating projects to ensure that we maximize the potential of our green collar workforce. (The full document can be found here.). Projects funded with stimulus dollars should:

- Create employment for a wide spectrum of workers, from low-skilled to highly skilled.

- Support local employment opportunities. Outsourcing occurs not only when jobs are sent overseas, but also when labor is imported into an area with an already trained and ready labor pool that can, and should, be employed.

- Create jobs that offer good wages, health care benefits and paid time off.

- Promote employment in environmentally sustainable areas, such as retrofitting building, brownfield redevelopment and urban forestry.

- Promote the retrofitting and maintenance of existing infrastructure, such as mass transit systems, roads and bridges.

Using these criteria to evaluate projects proposals will help rebuild our economy and create a greener, more sustainable city. For instance, using federal stimulus funds to create an "Efficiency Matching Fund" providing a 100 percent federal match for state-approved energy efficiency programs would help quickly channel funds to green job development. Every $1 invested in such programs saves $2 to $4 in energy costs for consumers, freeing up additional consumer purchasing power. Energy efficiency programs also bring us closer to environmental sustainability.

The economic stimulus must fund training and readiness programs to ensure there are enough skilled workers ready to do these tasks. The Consortium for Worker Education, the Association for Energy Affordability and the New York Industrial Retention Network developed a plan to integrate economic development and workforce development to promote energy efficiency. With funding, this proposed Green Jobs Center would include a training center to assess, train and place over 2,700 workers in the energy efficiency industry. The center also would provide business services for over 900 businesses seeking to expand or enter the energy efficiency market over a three-year period.

Finally, to ensure that stimulus spending creates jobs in the near future and new industries in the long term, it must include language that allows cities and states to give preference to local companies when they purchase goods and materials used in federally funded capital projects. This will nurture local green manufacturing and reduce the carbon footprint of projects by removing the need to transport products long distances.

The Wall Street disaster offers us the opportunity to build a new economic future. Wisely invested, the federal stimulus can generate the green collar jobs that will rebuild our middle class and create a more sustainable environment for generations to come.

J. Mijin Cha is director of campaign research at Urban Agenda, convener of the Apollo Alliance. The alliance is holding a public forum on Feb. 2nd to discuss the New Apollo Plan, the economic stimulus and New York City. For more information, visit www.urbanagenda.orgÂ

The Budget Outlook Goes from Bad to Worse

Left photo (cc) Nic McPhee

The Independent Budget Office's January Fiscal Outlook and other recent budget reports just might give Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the City Council members who extended term limits at least a brief twinge of regret. For the remainder of this term and probably for part of their next, they will confront increasingly grim economic and fiscal prospects. The mayor's November Plan, the modification of this year's budget approved by the council in December, already looks like ancient history.

The mayor in November forecast a $1.3 billion budget deficit for fiscal year 2010, which begins July 1, 2009. The Independent Budget Office now projects a $4.3 billion gap. While the mayor in November set the estimated 2011 deficit at $5.0 billion, the IBO now puts that number at $7.0 billion. A report by the state comptroller says the 2011 deficit could reach as high as $8.0 billion.

What has happed since November, of course, is that the economy has spiraled downward. The now-acknowledged recession is costing hundreds of thousands of people across the nation their jobs and causing plunging tax revenues at all levels of government.

The impacts of that recession were slow to affect New York City. But now everything has changed. Job losses in the city are accelerating and, with that come projections of sharper tax revenue losses and growing budget deficits.

The Employment Outlook

The IBO report says the city will lose 243,000 jobs the peak of 3.8 million jobs reached during the first quarter of 2008. Some 82,300 of those lost jobs will be in the financial activities industry, 48,900 in securities jobs alone.

In general, the IBO report paints a weaker job picture than the mayor did two months ago. Bloomberg forecast a loss of 147,000 private-sector jobs through this calendar year and assumed the number of jobs would begin to grow again in 2010.

The Revenue Slump

As a result of the jobs losses and overall deteriorating economy, business and personal income taxes will plummet, according to the IBO. The three business income taxes -- the general corporation tax, the banking tax, and the unincorporated business tax (mostly a tax on professionals like accountants and lawyers) -- tripled to over $6 billion from 2003 to 2007. By 2010, the IBO see them declining to $3.7 billion, a 38 percent drop in three years.

The office expects personal income tax revenues to drop by $1.4 billion from the current 2009 fiscal year 2010. And its sees only modest increases in revenues from the tax in 2011 and 2012.

There is some good revenue news. The most stable -- and by far the biggest -- of the city's major taxes is the real property tax, which, because of the complex nature of the tax, is much less subject to current economic conditions. The IBO says property tax revenues - after the 7 percent rate increase for the second half of fiscal 2009 approved by the council in December -- will total $14.4 billion this fiscal year, a 10.1 percent increase from 2008.

"Because of the gradual phase-in of past increases in property values and the second step of the tax rate increases, revenues are expected to continue growing at double-digit rates in 2010, rising by 11.8 percent to $16.1 billion," the report says. As the phase-in of increases in property values is completed, though, revenue growth will slow in 2011 and 2012.

The IBO projects that the other big city tax, the 4 percent city sales tax, will decline by 3.1 percent in fiscal 2009, to $4.7 billion, and by 7.1 percent in 2010 to $4.4 billion. Sales taxes, the report says, will rebound in 2011 and 2012, reaching $5.0 billion in the following two years.

Balancing the Budgets

The current and future deficits have forced the mayor into a new budget strategy. In recent years, the big surpluses, for the most part, have been carried over to cover expenses for subsequent years, making each year's budget balancing that much easier. In addition, the mayor placed $2.5 billion of the 2006 and 2007 surpluses in a new reserve fund, the Retiree Health Benefits Trust Fund, to be used to meet future liabilities for retirees' health expenses.

Today, both these strategies have faltered. The $1.8 billion surplus in 2009 that the mayor hoped to use to fill gaps in the 2010 budget has shrunk to $568 million, according to the IBO.

Furthermore, Bloomberg proposes to use more than $1.1 billion of the retiree health fund to make up for the anticipated growth in pension expenses caused by losses in pension fund investments. That move has caused some grumbling from the IBO and the state comptroller.

The IBO, for instance, says the new use of the retiree trust fund "undermines the city's goal of beginning to fund its enormous liability for future retiree healthcare expenses."

And the state comptroller's December report says that the move can be seen as "a sign of serious fiscal stress" that will shift the burden of paying retiree costs to future taxpayers. In contrast, the city comptroller in his December report on the state of the city's economy accepts the temporary use of the retiree money but urges a quick replenishment of the fund.

To fill the deficit, the mayor has asked agency heads to prepare for an additional 7 percent cut in expenditures, which would save $1.4 billion. He also has proposed an unspecified $800 million in new taxes. These moves would cover only half of the IBO's projected $4.3 billion deficit, although Bloomberg may come up with additional cuts and taxes when he announces his preliminary budget at the end of this month.

The State and Federal Role

That preliminary budget for fiscal year 2010 will represent the next step in what will likely be a tough five-month struggle to balance next year's budget and stabilize the city's longer-term fiscal condition. Uncertain state and federal politics complicate the picture.

New York State, which is more dependent on Wall Street revenues than the city, cannot help the city close its budget deficit. The best that can be expected is that cuts in state aid be kept to a minimum. The biggest problems for the city in Gov. David Paterson's proposed budget, as the IBO points out, are a proposed $600 million cut in state education aid and elimination of $327 million in state revenue sharing funds which - unlike education and other state aid - can be used to balance the city's budget.

The federal government could provide more help, particularly through a possible economic-stimulus plan. Some experts have proposed that the federal government pick up a greater share of Medicaid funding to help ease the budget crises in many states. The federal government currently pays half of New York State's Medicaid expenditures, and the state and the city pay the rest. This year the city will spend $5.6 billion as its share of Medicaid costs.

An increase in the federal portion would lower the state's spending on Medicaid. Those state savings, if shared with the city, would free up city money for other expenses or budget balancing. Unfortunately, though, as the IBO points out, it is not clear that any such federal aid would require the states to share the benefits with their local governments.

The alternatives to major federal fiscal help are the old stand-bys: more taxes or more cuts. That's a grim picture for the city.

In the meantime, all the economic projections remain uncertain, making budget planning even more difficult. Fiscal monitors disagree, for example, on when the city will come out of the recession. The city comptroller sees a turnaround starting in the middle of calendar 2009; the IBO does not see even slow job growth beginning until the second quarter of calendar 2011.

The IBO acknowledges that just a year ago, its analysts, like other economic forecasters, did not expect a U.S. recession. Now many agree with the city comptroller who last month acknowledged that "additional shocks to the financial system" could result in "a truly epic slump."

New Yorkers Rate Their Government

As the city's budget woes escalate, tensions between Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the City Council over taxing and spending also have increased. While the fight over where and how to cut certainly will continue into the planning for the 2010 preliminary budget, due out in just a few weeks, both sides might take a step back and look at the NYC Feedback Citywide Customer Survey, released in early December by the mayor and Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum.

What a close reading of this survey of over 24,000 city respondents, conducted by the National Research Center, a private firm, suggests is that New Yorkers have serious concerns about city spending and the effectiveness of a number of city services, including child protection, youth employment, homeless services, police-community relations, and protecting them from crime. Across-the-board cuts in these and other crucial areas -- as opposed to selective cuts based and new progressive revenues -- cast doubts on the mayor's budget strategy.

The Current Mayoral/Council Fight

With a vote on the modifications slated for today, the council has resisted its usual rubber-stamping of the November changes in the approved budget for the current fiscal year, which ends June 30. Much of this tension has focused on the mayor's plan to cancel this year's $400 rebate to residential homeowners and raise property taxes on all commercial and residential property in January by 7 percent.

The council issued a plan with alternative agency cuts, worth $170 million in savings in the current fiscal year, and over $325 million in 2010. The council also proposed an increase in the city hotel tax, from its current 5 percent to 5.875 percent, worth about $80 million in new revenues.

Meanwhile, with city tax revenues dropping faster than projected (and perhaps in frustration over the council's delays) the mayor on Dec. 9 issued yet another warning about next year's problems. The city's budget director, Mark Page, told agency heads in a memo to come up with plans for yet another across-the-board budget cut for fiscal 2010 -- this one for 7 percent, saving $1.4 billion.

The new reductions translate into a $527 million cut in education and $286 million for the police department. These would be on top of 5 percent across-the-board cuts already under way as part of the November modification and estimated to save an initial $1 billion.

The Public's Perceptions of City Services

While the mayor has called for across-the-board cuts in all these cases, however, the public, according to the new survey, takes a far more nuanced view of city services. Respondents see different service results in different agencies. The Bloomberg/Gotbaum survey can help us see this, offering a sense of what the public thinks about much of city government today.

To the mayor's credit, many of the survey's 34 questions are tough, asking the public to grade his administration in several direct-service areas. On the other hand, the survey uses a grading system that makes the results look rosier than the actual data show. The press release from the mayor's office, for instance, suggests that in five of six broad service areas, 85 to 92 percent of the responses were positive.

This results partly from a generous grading system. Respondents can award services one of four grades: excellent, good, fair and poor. The first three are all aggregated for a single positive score, while only the fourth response, poor, is left out. Lumping fair responses with more positive responses seems to set a pretty low bar.

In addition, grades for various parts of a service area are combined for a single index score. Averaging responses across a number of questions in this way dilutes a range of responses within certain services areas.

Take the sixth area noted in the press release, social support services, which has an Index Score (excellent, good and fair responses added together) of 58. That means 42 percent of the respondents thought such services were poor. Bad enough. But, if we raise the bar to consider the fair responses (35 percent) as less than positive, then only 23 percent of responses (good and excellent) consider the quality of social support services positive.

More specifically, the social support services index score of 58 aggregates scores from five questions. Three specific questions paint an even more negative picture. Some 44 percent of respondents, for example, thought child protection services were poor, 46 percent said the availability of youth employment programs was poor, and 48 percent said services addressing homelessness were poor. (In those same three questions fair responses ranged from 33 percent to 35 percent.)

The limitations of the index scores are also evident in the citywide public safety score. The overall score of 85 averages answers on services in five separate areas, including police and fire. A close look shows that the public judged fire and emergency services much more positively (76 percent and 67 percent of respondents said they were excellent or good, respectively) than crime control and police-community relations (which were rated only 42 percent and 40 percent excellent or good, respectively).

The different opinions about services persist in the neighborhood public safety index score, where respondents assessed the quality of services in their own neighborhood rather than citywide. Some 82 percent of respondents judged their own fire protection services excellent or good, and 72 percent thought their local emergency services excellent or good. Yet only 49 percent considered crime control and police-community relations in their neighborhoods excellent or good.

The survey includes questions about the city's largest budget area: public education. All respondents, whether they have children in public schools or not, were asked about the quality of public education and after-school programs. On public education, 78 percent of respondents said they were excellent, good or fair; on public after-school programs, 71 percent.

But in both questions, the fair responses were by far the largest. Only 38 percent of respondents judged public education excellent or good. Only 33 percent said after-school programs were excellent or good.

On the other hand, among those respondents who have at least one child in the public schools, the results were more positive. Fifty-six percent thought the public schools are excellent or good, and 57 percent thought after-school programs are excellent or good.

A section entitled "Overall Quality of Government Services" drew especially interesting responses. On the title question, 4 percent said the overall quality was excellent, 38 percent said good, 44 percent fair and 15 percent poor.

But in a second question in the same section, "Does the city government spend tax funds wisely?" the results were much more negative. Only 22 percent replied excellent (3 percent) or good (19 percent), while 37 percent said fair, and 41 percent said poor. Those numbers could serve as a sobering backdrop for the mayor and council as they fight over tax increases and agency cuts.

More Budget Data

The survey deals only with public perceptions. For those interested in more quantitative data, the mayor's Office of Management and Budget also released in December its latest Budget Function Analysis report, 513 pages that provide a highly detailed budget benchmark for current revenue sources and expenditures in 16 city agencies. (The education department, by far the city's largest, is not included.) In the case of the police department, for instance, the report lists 20 operating functions and what is spent for each in the $4.4 billion department budget.

Unfortunately, welcome as more budget information is, the Budget Function Analysis does not link program functions to performance outcome data, although each agency's report does offer an electronic link to the Mayor's Management Report. This is a reminder that the City Council has done better work than the administration in this area. Its little-known Budget Transparency Initiative not only breaks down agency budgets into program areas, but also includes relevant Mayor's Management Report data in an attempt to match dollars spent with performance outcomes.

All these tools could, of course, work together. The mayor's willingness to allow the new survey to test public perceptions of his administration's performance and the council's own focus on performance measures could generate a joint fiscal strategy that acknowledges the need for new priorities and sacrifice, goes beyond across-the-board service cuts and takes a serious look at a more progressive tax system.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.

Stated Meeting: Tax Bills on the Floor

The City Council has its own solution to New York's fiscal crisis: Don't tax New Yorkers. Tax tourists.

At least that is what Councilmember Lewis Fidler said Tuesday when he introduced a bill to increase the city's hotel tax by less than 1 percent. The bill has the support of Council Speaker Christine Quinn.

A less acceptable proposal, according to some council members, also was put before the council. It seeks to increase the city's property tax rate by 7 percent. Mayor Michael Bloomberg introduced the property tax legislation and argues the city must raise taxes and cut spending to close a yawning budget hole in fiscal year 2010 and a smaller one in this year's budget.

The mayor has not taken a positionon the hotel bill, though he has opposed similar proposals in the past.

These bills are the first tangible signs of the fiscal crisis in the council chamber, and they follow an unusual bout of mid-year public hearings on agency spending cuts.

Taxing Hotels and Houses

Fidler's bill (Intro 879) would increase the city's hotel tax from 5 percent to 5.875 percent, adding another $2.62 on an average $300 a room rate. The increase could raise an estimated $80 million in new revenue, say city officials.

For the current budget year, which ends in July, the city is facing an approximately $300 million budget gap. That hole widens to about $4 billion for next year's budget if the city does not cut spending or raise taxes this year, according to the mayor's November budget proposal.

The hike in the hotel tax, say supporters, could help close that gap, without deterring tourists from visiting the Big Apple.

"If you were to spend a week in the city of New York and spend $2,100 on your hotel, are you really going to change those plans because someone just told you that it went to $2,120?" asked Fidler. "I don't think so. I don't think $20 is going to stop anyone from coming to the greatest city in the world."

Not everyone is so sure. The Hotel Association of New York City vigorously opposes the bill, arguing the increase would drive away business and result in a loss of $533 million in room costs and tourist spending.

"Any tax increase would be gravely detrimental to the city's economic health," said Joseph E. Spinnato, the president of the association, in a prepared statement. "This increase could bring us back to the dark days of the 1990s when convention planners -- outraged by the fact that city policymakers would take advantage of our visitors to fix a budget hole -- boycotted our area."

The association argues that the city's tax is already 14.54 percent, factoring in the $2 per night hotel occupancy tax and the $1.50 Javits Center surcharge.

Fidler says, however, the "insignificant" increase does not compare to the skyrocketing hotel taxes during the 1990s.

"In this difficult economic climate, the truth is, as unfortunate as it is, everyone is going to have to pitch in," said Quinn. "This includes the visitors to our city."

A City Council spokesperson said the city would not have to receive approval from Albany to raise the hotel tax. Nor would it have to seek Albany's approval if the council chose to pass the mayor's legislation (Intro 887) and increase property taxes. The current legislation does not specifically state a 7 percent increase, though that is what the mayor has proposed in his November budget proposal.

Quinn said she has not taken a position on the property tax bill yet. She added the council has the power to amend the property tax bill and so could revise the 7 percent figure.

If approved, a 7 percent increase would raise about $576 million in additional revenue.

Women and Minority Businesses Boosted

In addition to introducing the tax legislation, the council unanimously approved legislation (Intro 888) encouraging companies that receive industrial or commercial tax abatements to contract with businesses owned by minorities or women.

The bill requires a business that receives a tax break for a project worth more than $1.5 million to solicit bids from at least three women or minority owned businesses for each subcontracting opportunity. The businesses would also have to identify firms in the city's minority and women businesses directory who could do the work.

If a firm does not comply with the bill, it could lose its tax break.

Budget Battle: Round 1

Â

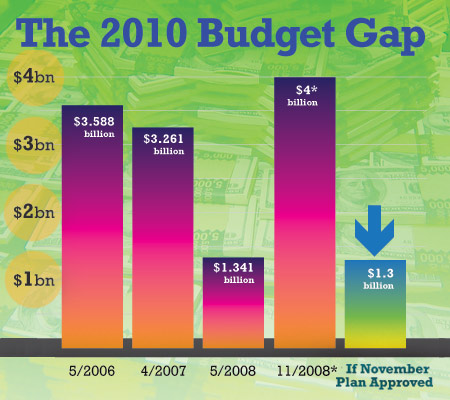

Image (c) Gotham Gazette

* This number is from the November financial plan, and includes the

fiscal year 2009 gap that has grown since the budget was passed in June.

See how the city has projected the budget deficit for FY 2010 over the years. Even in 2006, when the cityÂąs finances were in the black, the Bloomberg administration predicted a hole.

fiscal year 2009 gap that has grown since the budget was passed in June.

See how the city has projected the budget deficit for FY 2010 over the years. Even in 2006, when the cityÂąs finances were in the black, the Bloomberg administration predicted a hole.

Get rid of a property tax rebate or more than three police classes of 1,000 officers -- each will save about the same amount.

Increase property taxes by more than $200 for an average one- to three- family home or, maybe, slash supplies for public schools classrooms. Shut down the city's century-old dental program or add a five-cent tax on plastic bags.

Times are tough, say city officials, and we have to set some priorities.

This city budget season has started two months early, and the debate already involves lawsuits and squabbling. While it's not unprecedented, Mayor Michael Bloomberg's move to seriously revise city spending mid-way through the fiscal year gives some indication of how our economy has spoiled. Like it or not, some programs will have to be chopped.

Since the mayor announced his intention more than two weeks ago to cut city spending, rescind the $400 property tax rebate (a proposal whose fate remains uncertain) and increase property taxes by 7 percent come January, the City Council, uncharacteristically, has not waved any white flags. In some cases, they have called war.

Today is the last day of a weeks worth of hearings. Lines have been drawn and a victor is far from chosen. A vote is expected in early December.

Planning Early

In his typical fashion, Bloomberg's plan does not focus primarily on this year's gap, but the budget hole the city will face in 2010 and beyond.

He plans on cutting this year's budget -- through both raising taxes and reducing spending -- by $2.2 billion. (For more on the mayor's budget strategy, go here.)

That budget hole: $300 million.

Most of these cuts will go toward reducing the budget gap the city faces in fiscal year 2010. If the mayor's proposals win approval, they could reduce that deficit to an estimated $1.3 billion.

Why take these measures now?

"Everyone has to understand this is the only way we're going to get through this and have a future," Bloomberg said, sounding particularly doomsdayish, at a financial presentation earlier this month at City Hall.

The presentation, which normally takes place in January, sprang from the turmoil on Wall Street, which, Bloomberg argues, means the city needs to start cutting costs immediately -- seven months before the end of the fiscal year.

Most fiscal watchdogs say taking action early -- and addressing our fiscal problems before they turn too dire -- is characteristic of Bloomberg's approach to budget balancing.

"It's certainly consistent with the way he's operated since taking office," said Doug Turetsky of the Independent Budget Office. "He doesn't just wait until you get there to start doing things."

Even so, there still may be some wiggle room now. For the City Council, that comes in a $400 property tax rebate.

Tax and Spend Policy

Rarely do the City Council Speaker Christine Quinn and Mayor Bloomberg disagree publicly. Quinn has shepherded two controversial pieces of legislation -- both spearheaded by Bloomberg – through the council this year alone: term limits and congestion pricing.

But when it comes to delivering $400 checks to thousands of city homeowners, Quinn has staked out a position on one side, Bloomberg on the other.

Though the speaker declined to promise residents that they would get their rebate checks, which were supposed to be mailed in early October, Quinn said the council would do anything in its power to preserve the rebate.

"I can guarantee New Yorkers we are going to fight as hard as we can to get them those checks as quickly as possible," Quinn said at a press conference last week.

Part of that fight comes in the form of a lawsuit filed by council members Vincent Ignizio, James Oddo, Vincent Gentile, Lewis Fidler and Tony Avella. Assemblymember Louis Tobacco also signed onto the suit.

"This is just one of those out of touch with reality moments that you guys have over there from time to time," said Fidler addressing administration officials at a budget hearing on the rebate check. "I don't think you realize how much people who are living hand to mouth are expecting that check."

The council has argued the mayor cannot withhold the rebate checks without its approval -- which is a nonstarter. Bloomberg, who initially said he would not issue the check because the city had "no money," has started to back down. Last week, the mayor said he would work with the council to find "balance."

The rebate would cost the city $256 million. The tax hole for this year is $300 million. Do the math: The mayor's plan to increase taxes by 7 percent in January would bring $576 million -- more than enough to cover this year's gap. In fact, under his plan, the city would end the year with a surplus.

Again, it's about priorities.

Though the $400 rebate has become the council's cause of the moment, others say it's a regressive tax and the city should do away with it.

"They shouldn't have had the rebate in the first place," said Carol Kellerman, executive director of the Citizens Budget Commission. "This is not a need based amount. This is an amount if you are a single-family property owner. It doesn't matter if it's a townhouse on Fifth Avenue."

Who Wins and Who Loses

In addition to the tax increases, Bloomberg has proposed about $500 million in spending cuts in this fiscal year and more than $1 billion for next year's fiscal year. The agency cuts equal a reduction of 2.2 percent for fiscal year 2009 citywide.

Agencies have been ordered to cut their budgets by 2.5 percent for this year's budget and by 5 percent for fiscal year 2010. Some departments have received marginally more -- or less -- funding than others, but for the most part the cuts are across the board. (Check out a full funding breakdown here)

But for small agencies, a 2.5 percent cut can mean a lot. In addition, these cuts come on top of the spending reductions, which mostly hit social services agencies, that the council approved in June.

"They are looking to cut out anything that they are not required to provide," said Allison Sesso, deputy executive director of the Human Services Council. "This is just compounding cuts that were already taking place."

For example, the city plans to reduce the Department for the Aging's budget for "non-core social services," which has raised an alarm among some advocates. It also proposes to eliminate a $1.2 million program that provides adult day care to debilitated seniors and is doubling the co-payments parents pay to the Administration for Children's Services for day care programs from $1 to $2.

The mayor has also proposed eliminating 127 positions at the children's services agency, increasing caseloads for supervisors*. The city plans to close a job center and a clinic treating sexually transmitted diseases in Harlem and a homeless shelter at Bellevue Hospital Center.

At the Department of Homeless Services, the city will save $5 million in 2010 by providing incentives to city contractors for getting families out of emergency shelters and into public housing. Advocates say, however, the amount of available housing for these families remains stagnant.

The department also plans to require homeless working families to contribute to the cost of their shelter, which could bring in about $1.3 million next year.

For some advocates, that move touches a nerve.

"Many families actually save money while they're in a shelter," said Patrick Markee, a senior policy analyst at the Coalition for the Homeless. "It seems counterproductive and a little bit cold hearted."

Reductions in Blue

The Police Department plans to do its part to close the budget gap by putting fewer cops on the street. According to Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly, the department will cut new hires by half, eliminating one of the two yearly officer-training classes. Normally, police academy classes begin in January and July, and slightly more than a thousand officers graduate from each class. The elimination of the January class will save $36 million next year, but it will bring the department’s force to its lowest level in years. Along with reducing the number of new recruits, Kelly said, further reductions will come through attrition and a cut in civilian staffing, generally in clerical, administrative and custodial positions.

Before Bloomberg mandated the budget cuts, the department had planned on a peak headcount next year of almost 37,000 uniformed officers. At a joint hearing of the City Council’s public safety and finance committees on Nov. 24, council members expressed concern that crime would rise with fewer officers on the street. Kelly countered that the overall crime rate has decreased by 28 percent since 2001, when there were about 40,000 officers on the force—the department’s all-time peak.

"We’re going to do everything we possibly can to continue to reduce crime in this city," Kelly told committee members. "We’ve done it effectively at a time when we lost some 5,000 officers. Crime has still come down and it's safer than its ever been."

Public safety committee chair Peter Vallone Jr. was not convinced. While overall crime has fallen, Vallone said, certain violent crimes have increased: Murder is up 6 percent, and rape and burglary are each up 2 percent so far this year. And, he said, the decline this year in overall crime is the smallest so far since 2001.

"The NYPD always says it can do more with less, but at this point, Batman would have trouble doing more with the amount of resources we have allotted," Vallone said in a statement issued after the hearing. "If public safety suffers, everything suffers."

Vallone is particularly worried that any rise in crime could exacerbate New York’s economic crisis, affecting tourism, retail and real estate.

The department plans additional savings by shifting additional law enforcement duties to traffic enforcement agents. For example, until now, only uniformed police officers could ticket vehicles for obstructing traffic at intersections. Gov. David Paterson recently signed a bill requested by Mayor Michael Bloomberg that allows the city’s traffic enforcement agents to issue these tickets.

Classroom Cuts

Even city's public school have not escaped the current round of budget cuts. The administration has proposed $180 million in cuts to the Department of Education's $21 billion budget this year and $385 million next year. In June, the department took a $200 million reduction but, partly through the efforts of the council, school classrooms were spared.

This time around though, classrooms would see a $103 million reduction. Where exactly that would fall will remain largely up to individual principals, although no teachers will lose their jobs. "The principals have made it clear that none of these cuts are easy or without pain, but they expected these cuts," Deputy Chancellor Kathleen Grimm told City Council.

For the first time, the administration proposes to reduce spending at the District 75 schools serving handicapped students – although by a relatively modest one half of one percent.

Other cuts will come in administration where the department proposes to eliminate 338 positions, cut back on the Teaching Fellows program, trim expenses on meetings and eliminate science assessment. Some maintenance positions serving schools will also be lost.

Given how volatile school spending cuts tend to be, Friday's hearing on the reductions was relatively low key. Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum reiterated her concerns about the department's spending on its so-called accountability initiative, Fidler suggested the school use energy efficient light bulbs, and John Liu wondered how much the department had spent on an ill-fated plan to centralize kindergarten admission.

There were, though, apparently no real fireworks. Those could come at public hearings today. On the other hand, almost everyone at the hearing realized this round of cuts could be the relative calm before the storm. The state has not enacted any cuts for now, but everyone anticipates that will change. With the state providing 41 percent of the Department of Education's funds, how much of the cuts could fall on city schools remains anyone's guess.

"I make it a policy not to predict what Albany will do," Grimm said.

Other Battlegrounds

At another of many budget hearings last week, Councilmember Gale Brewer questioned the administration on how it collects taxes from vacant buildings.

Sitting at the very top of the dais, Brewer couldn't help but add a closing remark.

"Don't cut the libraries," she jabbed.

A typical council-mayoral battleground, libraries under the budget plan would cut back hours to an average of five and a half days from the current six. Some branches, said an aide to the council's libraries subcommittee chair, Gentile, would only be open for five days, while others will be budgeted for the extra half day. The library cut would save $8 million in this fiscal year.

The council will also almost certainly object to cuts at the police department and the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. The administration has proposed delaying a police class of 1,000 officers, reducing the overall headcount at the department. The training program at the fire department's academy will be cut from 23 weeks to 18 and several engine companies will lose their night hours, for a combined savings of $7.5 million.

Councilmember Peter Vallone, head of the council's public safety committee, has made this police headcount reduction part of his checklist for elimination.

The mayor's proposal to eliminate the city's dental program for children, which began in 1903, is also drilling up some ire. The program serves 1 percent of the city's kids and costs $2.5 million.

Looking Forward

Most agree the worst is to come.

All of these cuts do not factor in an estimated $12.5 billion deficit in Albany, which is sure to translate into deeper slices in school aid statewide. This year, the city received $11.7 billion from the state -- about 20 percent of the entire budget.

The State Senate is set to hold a special session next month to consider cuts by Gov. David Paterson. The governor is also scheduled to release an updated fiscal response to the crisis in December.

These budget revisions also do not take into account debilitating deficits at the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and the New York City Housing Authority. The city's public hospitals network, the Health and Hospitals Corp., is also struggling, say officials.

Our fiscal troubles are far from over.

"I think this is a very difficult budget year, but you typically don't see these budget modifications change very much," said Markee. "We're a lot more worried about what's going to happen in next year's budget."

*When this story originally appeared, it gave the impression that all caseloads at the Administration for Children's Services were increasing. In fact, regular caseworkers will not be affected by the budget cuts. Some supervisors, who had taken on only a few cases in the past, will now have a full caseload.

Dara L. Miles contributed reporting to this story.

The Mayor's Budget-Cutting Strategy

Photo (cc) Pixotropic

Mayor Michael Bloomberg's November budget modification is interesting for two reasons. First of all, it underscores the city's short-term budget health. Modifying this year's budget to keep it balanced remains a relatively easy task. Quite unlike the alarms spilling out of Gov. David Paterson's office, the modification for the city has no sense of immediate urgency.

(For more on the cuts and the City Council's reaction to them, see related story.)

Secondly, despite that, it is indeed full of warnings about the city's mid and long-term fiscal prospects. Further, it includes several hints of how the mayor will address big deficits in 2011 and 2012, including drawdowns from the Retirees Health Benefits Trust Fund and some less-than-progressive tax increases.

Short-term Budget Health

The city's conservative revenue estimates and the mayor's habit of building budget surpluses, then rolling them over into future years -- $6.5 billion last year alone - thus far have cushioned the economic decline's impact on city services. In fact, the November modification accomplishes its first priority -- re-balancing this year's budget -- quite easily. The budget shortfall at the moment (mostly from a drop in business income taxes) is only $300 million, a tiny fraction of a $60 billion budget, and the mayor's already implemented cutbacks this year - about 2.2 percent of agency spending - more than cover it.

The controversy has arisen from the mayor's two revenue recommendations -- rescinding the 7 percent property tax rate cut in January, worth $576 million in new revenues, and trying to cancel this year's $400 rebate for homeowners, worth $256 million. These revenues and the agency cutbacks together actually would increase the city's budget surplus for this year by nearly $1 billion. Assuming all this happens, these moves, along with other anticipated surplus and reserve funds, would put the city on the road to a 2009 surplus of over $2 billion.

The City Council usually just rubberstamps modifications. This time, though, the property-tax changes became the focus of council ire.

At the first of the hearings, on Nov. 17, council members grilled Bloomberg budget director Mark Page. During the questioning, Finance Committee chairman David Weprin produced a document -- from the mayor's office -- saying the rebate could not be canceled without council approval. Since the council has indicated it would not agree to this part of the mayor's plans, it seemed the checks would soon be in the mail.

On Wednesday, though, Bloomberg indicated he would continue to block the rebate, setting up a showdown between him and the council. By the end of the week, the mayor was striking a somewhat more conciliatory tone, opening the way to possible negotiations.

Whatever the result of this dispute, the mayor's proposed cutbacks continue his style of budget balancing thought across-the-board agency cuts. No priorities here: Not only does education share in the cutbacks - over 2 percent or $181 million this year and 5 percent or $385 million next year - but such popular agencies as the police department ($45 million this year, $167 million next), libraries (which on average will be open half a day less than they are now) and cultural organizations ($3.8 million this year, $7.2 million the next) all take hits.

The Education Cuts

One of the significant debates in current and future council hearings likely will focus on the actual impact of big cuts in education. The mayor argues that the cuts will be in administration and other non-classroom areas. The council will respond with its own list of administration cuts, saving $150 million, Council Speaker Chris Quinn said in an October speech to the business-sponsored Citizens Budget Commission

As the council and the Department of Education joust about "administration" cuts, they might look at the Independent Budget Office's new fiscal brief "The School Accountability Initiative: Totaling the Cost." The study - hampered, as the IBO puts it politely, by "the limited information available to outside agencies through the city's financial data systems" (See Gotham Gazette's "High Stakes Test" for more) - shows how slippery the definition of administration can be.

The IBO estimates that administering the schools' new accountability initiative, which prepares the school progress reports or report cards and launched in April 2006) cost $130 million last year, and will cost $105 million this year. Alternatively that $130 million could buy 13 million paperbacks at $10 each, or about 13 books for every student in city schools, pre-K to 12.

According to the education department, however, using a more narrow definition of accountability, the initiative cost only $37 million last year and $48.5 million this year.

Future Problems

The mayor's November modification takes care of the small 2009 budget deficit, and, if the council buys into the January 2009 property tax increases, also reduces the projected 2010 deficit from $2.3 billion to $1.3 billion. That too would be manageable.

Then the real trouble begins. For instance, the first major sign of fiscal stress stemming from Wall Street problems is the modifications projection that the city in 2011 and 2012 will have to make up for approximately $1.1 billion in city pension funds lost recently in the stock market.

The mayor proposes to solve the pension fund problem by taking a total of $1.1 billion from the Retiree Health Benefits Trust Fund in 2011 and 2012, a mayoral discretionary (or "rainy day") fund originally designed, as its name suggests, to meet city liabilities for future health expenses of city retirees. The fund received a total of $2.5 billion from budget surpluses in 2006 and 2007.

Both Quinn and City Comptroller Bill Thompson have in recent years proposed a legislated rainy day fund that would set the terms for a fund draw-down in a fiscal crisis, and it will be interesting to see how they respond to the mayor's sudden change in the use of that fund.

Even with drawdowns from the retirees fund, deficits for 2011 and 2012 will average $5 billion. The current modification looks ahead, and its revenue options in the modification for 2010 provide at least a hint of where Bloomberg might go with tax policy. However, his short laundry list of tax increase options reads more as a partial primer than as a comprehensive revenue plan, interesting as much for what it leaves out as what it includes.

Tax Options

The city's current four-year fiscal plan already assumes that, in July 2009, the average property tax rate will revert to its 2002 to 2006 rate and stay there. The proposed November modification, as noted earlier, would simply make the rescission effective in January 2009 rather than July.

This means other revenues will be necessary. The modification offers several possibilities to meet the 2010 deficit: three options for increases in the sales tax - the most regressive of all taxes -- and two options for across-the-board rate increases to the personal income tax.

Notable for their absence are any options to increase business taxes or to restore a more progressive personal income-tax rate structure. In a city that overwhelmingly voted for Barack Obama and, presumably, for his progressive tax agenda, including tax cuts for working and middle class families (see "Candidate Talk Taxes"), the mayor's options of 7.5 percent and 15 percent across-the-board increases in the personal income tax rate hit these same, most vulnerable of taxpayers.

Six years ago, as part of the huge November 2002 modification, the same mayor increased income tax revenues in a progressive way, by creating two temporary, three-year top rates for higher-income taxpayers. Other taxpayers' rates remained unchanged.

An across-the-board 7.5 percent increase would raise $585 million in 2010; a 15 percent increase would raise $1.2 billion. The 7.5 percent increase would cost a taxpayer with taxable income between $50,000 and $75,000 an additional $116. A 15 percent increase would cost her $233.

A taxpayer with taxable income between $75,000 and $90,000 would pay, with a 7.5 percent increase, an additional $178, and with a 15 percent increase, $356 annually.

The regressive sales tax options include increasing the city sales tax from 4 percent to 4.25 percent, raising $292 million in 2010, or to 4.125 percent, which would raise $146 million. Reinstituting a sales tax on clothing (the current exemption reduces the sales tax's regressivity) would raise $436 million.

Taking two of these options -- raising the sales tax rate to 4.25 percent and increasing the personal income tax across-the-board by 15percent -- would raise $1.5 billion in 2011, only 30.5 percent of that year's projected $5 billion deficit.

What then? The mayor in a brief statement in the modification said, "We have tried to strike a balance between increases in revenue and decreases in planned spending," so the balance in 2011 would presumably come from further unspecified (across-the-board?) agency cuts.

The mayor should be commended for providing extensive information in the November modification. The summary document alone runs 55 pages. But there is minimal explanation of the data in the summary and, more importantly, too few options and too little big thinking. In its February 2008 Budget Options for NYC, for instance, the IBO listed 29 revenue options.

The IBO lists five scenarios for the personal income tax alone. All would make the tax more progressive. The most familiar, a version of the 2002 increase, would add two top rates. A 3.9 percent rate would go into effect for joint filers with incomes of $225,000 and above and a 4.2 percent rate would kick in for joint filers with income of at least $450,000. This would raise over $600 million in 2010 and would leave the rates for working and middle-class New Yorkers unchanged, a big plus in a slumping economy.

One other big revenue producer is worth noting again, but it would require changing the conversation between mayor and council. Instead of debating how to cut $200 million or $400 million from the education budget, why not look seriously at tolling the East and Harlem River bridges? Kids vs. cars? The IBO estimates the city could raise over $800 million with a toll plan.

The pain ahead for New Yorkers is not likely to be "across-the-board," and at some point the budget decision-makers will need to set some priorities. Across-the-board tax increases and across-the-board service cuts don't meet that challenge.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

The Public Speaks on Budget Cuts

For David De Porte, the Department for the Aging's intergenerational program doesn't just provide him with companionship. It gives him a set of eyes.

De Porte, a blind lifelong resident of the West Village, meets with teenage volunteers who help him shop for groceries, fill out paperwork and check prescriptions at the drug store.

"Guide dogs are great, but they can't read labels, and people in stores are not always willing to help," De Porte, a freelance writer, said. Xia, his German Shepherd guide dog, lay quietly by his side during his two minute testimony in front of the City Council yesterday.

The intergenerational program costs more than $1 million. Mayor Michael Bloomberg's budget proposal, released earlier this month, would eliminate that funding.

De Porte was one of many members of the public who got their first opportunity to opine on the mayor's budget proposal Monday. The proposal cuts -- by both increasing taxes and slashing spending -- $2.2 billion from this year's budget. The funding decreases would shrink next year's anticipated deficit to $1.3 billion.

For more on this year's budget cuts, check out "Budget Cuts: Round 1" and our breakdown of each department's cuts.

Cuts to Culture

Among City Council members, the elimination of a $400 property tax rebate has caused the most alarm, but the scores of residents who came to City Hall were far more concerned over the cuts to cultural, health and aging programs.

From doing away with the city's century-old dental program to cutting day care programs for debilitated seniors, the city, residents said, is eliminating the programs that are needed most when times get tough.

As she wound up small chattering teeth toys, Judy Wessler, the director of the Commission on the Public's Health System, asked: "We're talking about children losing their teeth right?" -- referring to the axing of the city's dental program. She let the teeth loose, and they danced off the testimony table.

The heads of the city's most prominent cultural institutions, like the American Museum of Natural History, urged the City Council to revise the mayor's budget proposal to soften the cut's impact. While all of the city's agencies saw an approximately 2.5 percent cut in this year's budget, cultural institutions argue their funding has been cut far more drastically.

According to figures provided by the Cultural Institutions Group, groups have seen cuts as high as 42 percent in city subsidies. The American Museum of Natural History's city funding has been cut by 22 percent -- a total reduction of $2.8 million -- in this fiscal year, while Lincoln Center's has been slashed by 42 percent. The entire cultural consortium has seen a total loss of 18 percent, according to figures provided by the group.

A reduction in programs for the city's most vulnerable, including residents of public housing and senior citizens, drew extensive criticism. The mayor slashes funding for local nonprofit groups that, critics say, will drastically reduce the local services they can provide. Many wondered what would happen to the care programs for seniors with Alzheimer's or the arts and education classes at their local community center.

"Is the city of New York so impoverished that it must rob these seniors of a last modicum of dignity?" asked Patricia Dolan, executive vice president of the Queens Civic Congress.

The mayor's plan will reallocate community services at the New York City Housing Authority saving the city $18.6 million. The cuts, though, will result in the closing of 18 community centers, one in Karen Anglero's Flushing project.

"New York City Housing Authority residents are the city within the city, and we vote, and we'll remember in November 2009," said Anglero.

Where the Cuts Come From

Â

The "old" budget figures were in the city's 2009 fiscal budget, approved by the City Council in June. The "new" figures are from the budget modification the mayor proposed in November, which is still awaiting City Council approval. For more on the specific items being cut and the debate over taxes and spending see Bugdet Battle: Round 1.

> >

|

Budget figures do not include debt service, pension costs, and long term employee health care costs.

*Library figures are skewed because the administration pre-paid costs in the previous budget year. Therefore, budget cuts for major library branches are 2.5 percent for this budget year and 5 percent for fiscal year 2010. Some budget increases, including the police department, are attributed to increases in labor union contracts.