Running Against Albany on Manhattan's Lower East Side

UPDATE:

Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver overcame two spirited challenger to win the Democratic primary in his Lower Manhattan district with 68 percent of the vote.

He is likely to face an easier time in the general election. His opponent, Danniel Maio ran for Manhattan borough president in 2001, State Senate in 2002, City Council in an election in 2003, and the U.S. House of Representatives in 2006 and lost every time. Maio has challenged Silver to a public debate about the economic crisis, but no debate has taken. place.

According to his 32 Day Pre-General filing, Silver had more than $2.5 million on hand at the end of September and had collected $23,000 of that in the previous few months. Maio had collected no money in the reporting period and showed a negative balance of $575.

* * * * * * original article * * * * *

Sheldon Silver doesn't have a campaign Web site, and his page on the State Assembly's official site is barely distinguishable from those of the other 149 members of the Assembly. Centering on perfunctory details -- contact information, office addresses, a map of Silver's Assembly district -- the page extols visitors to "Take the 2008 Summer Reading Challenge!"

While the Speaker of the Assembly's less-than-formidable Web presence may mean that governing New York leaves scant opportunity to post YouTube clips and friend voters on Facebook, it could be another sign of changes in the political world that Silver has dominated as leader of the State Assembly and one of Albany's "three men in a room."

Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno, who held office since the 1970s, suddenly announced his retirement in late June. His State Senate could swing to the Democrats after decades of Republican control. And after 32 years in office and 22 years without a primary opponent, Silver now faces two separate challengers in the Democratic primary to represent the 64th district in Lower Manhattan.

Silver's two opponents, Luke Henry and Paul Newell, have each used social networking sites and their own Web pages to tout their message that Silver is out of touch with voters in a year when the mantra is change.

When Henry talks to voters on the street, he sometimes takes a camera along so he can post people's reactions in online videos. For his part, Newell has been endorsed by BlogPac, an online activism site. "The blog stuff is great. New media can play a big roll in finances," he said.

Both challengers have taken some cues from Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama, whose message of change and extensive online organizing effort paid off in his campaign against Hillary Clinton.

"I think change is an easy sell," Newell said. "I don't think people in the community need to be convinced."

But if Silver doesn't have a glitzy campaign Web site, he does have a few things Henry and Newell lack: 32 years in the Assembly, a record lauded by many district voters and the power that comes with being the Assembly leader. Labor unions, a key source of campaign volunteers and cash, strongly support his re-election. As of the last filing deadline in January, Silver's campaign had raised almost $3 million, according to state Board of Election records.

At the same filing deadline, Newell had around $17,500 and Henry had no funds to report at all. Both candidates say they are on track to meet their fundraising goals by the next reporting date in July.

Experience vs. Change

On the issues, Silver and his challengers often agree. They think rents should be regulated, that the Rockefeller Drug Laws should be reformed, and that the mayor should have control over New York City schools.

What they disagree on is how decisions should be made in Albany.

Newell and Henry think the process in the state government must change and say one way to accomplish that is to defeat the man who has run the Assembly since 1994.

"If you reform the rules by which Albany operates, it takes a strong step toward progress," Henry said. "Speaker Silver is the chair of the Assembly's rules committee. Any new speaker would have to support rules that empower individual legislators. Until we change the structure in Albany, change will never happen."

According to both challengers, unseating Silver would have symbolic value as well.

"If the Assembly has to vote for a new speaker because of a 33-year old community organizer running on a reform platform, things will change," said Newell, who has never run for an elected office before. "I believe Albany is going to change dramatically when I arrive."

In emphasizing Silver's removal, both challengers devote Web site space to Silver's negative or ambivalent press, including a recent New York Magazine profile of Silver titled "The Obstructionist." Both Henry and Newell offer themselves as the political equivalent of Drano, but in their effort to transform the political machine, they haven't convinced everyone they can handle politics on the inside.

Their lack of political exeprience helped convince the Downtown Independent Democrats, the self-described "reigning Democratic club in a wide swath of Lower Manhattan," to endorse Silver, said club president Sean Sweeney.

"The fact that one of them would not drop out shows that they're not politically experienced enough to be the representative of one of the most important Assembly districts in the country," Sweeney said. He predicts the two will split the opposition vote, guaranteeing a Silver victory.

The Third Man?

Even Silver's supporters acknowledge his method of leadership has its shortcomings. His willingness to work the system has won him praise and ire over the years, but his critics, including the New York Times editorial board and Mayor Michael Bloomberg, whose congestion pricing program recently died in Silver's Assembly, have lambasted the speaker for working behind closed doors and not promoting open debate in the Assembly. Many target a lack of transparency as Silver, Bruno and the sitting governor -- the three men in a room -- made so many key decisions out of public view.

"Is it the best exercise in democracy? No. Is it efficient? Yes," Sweeney said. "We're a reform club and we don't agree all the time with some of Silver's politics. But a legislator has to do for his constituents."

He added, "I wouldn't want to go play poker with him in Atlantic City."

The Silver campaign dismissed the "three men in a room" description of the Albany legislative process as a political myth.

"All the members of the Assembly exhaustively, collaboratively, openly come to consensus," said Jonathan Rosen, the spokesmen for Silver's re-election campaign. Rosen compared Silver's role to that of Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, who negotiates with the president on behalf of Congress.

In fact, the leaders in the New York State legislature have more power than their counterparts in most other states and in Congress.

"Power in the New York State Assembly and Senate is much more centralized than in many, though not all, states," according to Justin Phillips, an assistant professor in political science at Columbia University.

Phillips said the Senate majority leader and the Assembly speaker could change that, but that is not likely to happen.

"First, it would mean giving up some of their influence over legislative outcomes - something that legislative power-brokers are very reluctant to do," Phillips said. "Second, decentralization within the legislative chambers may also bog down the lawmaking process - it is pretty darn efficient to leave responsibility in the hands of just a few people."

Silver's Record

Despite his legendary political skill, Silver hasn't always come out on top.

Take the rent regulation battles of 1997 and 2003, involving Bruno, Silver and then Gov. George Pataki. Silver held staunchly pro-tenant views, but in the end, rent regulations were weakened. This was seen as a loss for the Democrats, said Jenny Laurie, director of the Metropolitan Council on Housing, a pro tenant group.

Silver, she said, "was out-maneuvered on some issues and perhaps didn't understand how meaningful some of these changes were."

Laurie called the secrecy that governed these closed-door negotiations "customary."

"It's how the Senate and the Assembly and the governor have worked," she said. "I think there should be open debate on all these issues, and not just on housing issues. There's a lot that could be more democratic."

But when Silver comes up victorious in the political game, it earns him loyal voter support. Sweeney hailed Silver for blocking plans to build a West Side stadium for the Jets football team. Henry shared Silver's opposition to the stadium, a Bloomberg project, but decried how Silver met his ends. The stadium required approval from Bruno, Pataki and Silver, who ultimately vetoed the project despite Bloomberg's yearlong pursuit of his support. The Henry campaign described Silver's move as the "implementation of legislative tactics to further his agenda."

In a similar move, the speaker did not allow Bloomberg's plan for congestion pricing, which would have charged people for driving into parts of Manhattan, to come to a vote in the Assembly. Newell said that showed the speaker's "contempt ...for the democratic process."

The Challengers

For better or worse, Silver is a known commodity. But who are his opponents?

Newell, a former community organizer, is an Obama delegate to the Democratic National Convention. His campaign has seized on this fact to suggest that the race in the 64th will produce the same insurgency-beats-the establishment narrative that came to define the national primary between Obama and Hillary Clinton, who Silver supported as a superdelegate. Newell even released a poster of himself posed as Obama above the word "Obamawitz."

"I don't make promises that the sun will shine down upon us on the day that I walk into the Assembly, but I do believe that we would begin to have a process that will allow progress," he said. "And if I had to pick a year to be a 32-year incumbent, I would not pick 2008."

Henry jumped into the race shortly after Newell, and his candidacy has struck some observers as so unlikely that there have been rumors that it is designed to split the opposition vote and so ensure Silver's re-election. Henry pushes an anti-establishment message about wrestling power from Albany regulars. An expecting father who only moved to the district last year, he said he decided to run to change state government.

"I hoped when Spitzer got elected there would be real change in Albany. I didn't see it," said Henry, who was recently endorsed by Democracy for New York City, a volunteer-driven non-profit political action committee. He has the support of former District Leader Norma Ramirez and former Assemblymember Nelson Antonia Denis.

For his part, Silver doesn't appear to be entirely dismissive of these potential threats. He has hired BerlinRosen, a public relations firm, to run his primary campaign. Focusing on the speaker's record, the campaign is portraying Silver as a neighborhood staple and pushing a "neighbors talking to neighbors" line to describe his base of community support.

And while the 64th district has undergone some demographic shifts since Silver was first elected, big questions go unanswered until primary day on September 9. Is the Orthodox Jewish community from which Silver hails still a significant voting bloc in his district? Will the youth vote turn out for a state primary election? Can online organizing make up for being outspent? Is 2008 really a bad year to be an incumbent? And is Albany really going to change?

Related Links on District 64

"The Obstructionist," (New York Magazine)

Â

A Tougher Year for Incumbents

(This article was updated on June 24 to reflect the resignation of Senate Majority Leader Jospeh Bruno.)

As job security fades for most New Yorkers, it has remained for members of the New York State Legislature. Once elected, they keep an almost legendary hold on their posts. Re-election rates have been said to reach 98 percent and likened to members of the North Korean government. Members of the legislature have won re-election after being indicted, arrested and caught in various compromising positions.

A House Divided in Washington Heights

First in a series of articles on the issues and candidates in the city's 2008 elections for state legislature and other offices.

No one will know for sure until polls close on Nov. 4, but that could change in 2008. The combination of term limits in New York City, the resignation of longtime Senate Majority Leader Joe Bruno and a sense by some Democrats that they could finally capture the Senate -- and with it control over state government -- has upset the traditional political calculus. In fact, many observers attribute Bruno's decision to leave the Senate at least partly as an indication that he too saw the arithmetic on the wall.

In the months running up the September 9 primary and then on to the Nov. 4 general election, Gotham Gazette will provide in-depth coverage of many of the competitive races in New York City. (The first of articles on an individual race -- this one covering the primary contest in Manhattan's 72nd Assembly District -- appears today.)

What's At Stake

Every two years, all seats in the State Legislature are up for grabs. This includes the 91 Assembly and State Senate seats for New York.

In most years, though, few incumbents face credible challengers. In the 2004 legislative races, nearly 60 percent of incumbents either ran unopposed or faced an opponent who had raised less than $1,000.

Political professionals cite a number of reasons for this. Primary contests for occupied seats remain rare and, in the general election, the drawing of district lines tends to favor incumbents, making some districts heavily Democratic and others heavily Republican -- discouraging closely fought contests.

Many experts believe the two major parties in New York had a kind of non-aggression pact. The Republicans would control the Senate and Democrats the Assembly. That is the way it has been since the 1960s.

It could change this year.

For one, the Democrats have moved closer to capturing control of the Senate. Following a special election in 2008, which brought a rare win by a Democrats in an upstate rural district, the GOP edge was reduced to a single seat. Gov. Eliot Spitzer's resignation made the situation a bit more complicated, since the Republican senate majority leader may now get to vote in the event of a tie, but the Republican control remains tenuous.

And it goes beyond the arithmetic. Republicans have been losing strength in New York State in general -- the party lost three seats in the state' delegation in the U.S. House of Representatives in 2006, and both senators and the governor are Democrats. Pundits see 2008 in general as shaping up to be a strong year for Democrats, and with the collapse of Rudy Giuliani's presidential bid, the GOP has no clear standard bearer in the state.

The Democratic zeal for taking over the Senate was fueled by Spitzer. Since taking office, Paterson has reportedly retreated from that fray, trying to foster détente with Bruno. But in many districts, the lines have already been drawn.

What It Means for New York

As a Democratic city, New York would seem to have everything to gain from a switch in the Senate. If Malcolm Smith, now Senate minority leader, remained head of the Democrats, it would mean that all three men in the room -- Paterson, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and Smith -- would be New Yorkers. Many progressive groups in the city, particularly those involved with housing and various social issues, have seen Democrats as more supportive of their causes.

Other influential groups in the city have managed to curry favor from both sides of the aisle. The healthcare workers union, 1199, allied itself with Bruno and backed Republicans in individual contests. The teachers union has also backed Republicans and has seen the Republicans support them, most recently on a bill that prevented the city from linking decisions on teacher tenure to their students' test scores.

Rather than backing either party, observers say, labor has been using the volatile situation in the capitol to press its programs.

"Labor is in a good place," said Richard Iannuzzi, president of New York State United Teachers, told the New York Times. "The atmosphere in Albany, for a variety of reasons, has been somewhat chaotic and combative, and that's allowed us to use our ability to be consistent to our advantage."

On the other hand, the Working Families Party, which has strong ties to labor, appears to be pushing for Democratic gains. It has abandoned some Republicans it backed in the past in favor of their Democratic challengers.

Weakened though they may be, the Republicans have one powerful ally in their quest to keep control of the Senate: Mayor Michael Bloomberg. In the past two years, the purportedly independent billionaire mayor has given at least $900,000 to Republican legislative campaign committees -- not counting any donation to individual candidates.

Bloomberg has indicated a willingness to extend his support beyond cash. Earlier this year, his Department of Education named a Queens school for Frank Padavan, a Senate Republican facing a Democratic challenge. Under city regulations, schools are not supposed to be named for living people but Chancellor Joel Klein defended the move on the grounds that this was not just a school -- but an entire campus.

Bloomberg said his moves are simply evidence of his commitment to helping people who help New York City. The Republicans "have been there for us," Bloomberg said earlier this year. "They've come and stood for the city a number of times when we needed to have a voice in Albany and didn't have that voice from the Assembly or from the governor." This was before Paterson's ascension and Bruno's resignation.

It is unclear how much of Bloomberg's enthusiasm has been for the Republican senators as a whole and how much of it was for their leader, Bruno, who Bloomberg repeatedly praised. Certainly Bloomberg has had problems with the Democratic Assembly. Silver vetoed Bloomberg's plans for a West Side stadium, the Assembly did not vote on Bloomberg's congestion pricing scheme and it has stalled his solid waste management plan. Of course, the GOP has not always taken the mayor's side either.

Up for Grabs

The situation has prompted a number of comparatively strong Democratic contenders to take on Republicans for Senate seats. Adding to the competition are some politicians from New York City who will lose their City Council seats to term limits at the end of 2009. Looking for their next political job, many have turned to state government -- where, for now at least, term limits do not exist.

Here are some hot Senate races cited in Capitol Confidential. Let us know about ones we might have missed. One caution, though, candidate lineups will not be final until petitions are filed -- and challenged -- later this summer.

3rd Senate District: This seat from Suffolk County is one of two (along with the 15th -- see below) that Senate Minority Leader Malcolm Smith has identified as key to Democratic hopes of winning the Senate. The 82-year-old incumbent Cesar Trunzo won with 53 percent of the vote -- and with Working Families Party support -- in 2006. Now, though, the Democrats seem to be acquiring strength in the area, and the Working Families has decided not to back Trunzo.

The party, along with Smith, is supporting Brookhaven Town Supervisor Brian Foley. But Jimmy Dahroug, who has sought the seat unsuccessfully before, wants another crack at Trunzo and seems likely to force a primary contest.

Following Bruno's resignation, some have speculated that Trunzo might follow Bruno into retirement.

7th Senate District: This Nassau County district was the scene of a contentious-- and expensive -- special election in February 2007 after then Republican Sen. Michael Balboni resigned to become state homeland security chief. Democrat Craig Johnson won that election, but the Republicans would like the seat back and hope Plandome Manor Mayor Barbara Donno can accomplish that task.

11th Senate District: Frank Padavan has represented this part of Queens for more than 45 years. This year, though, a term-limited City Council member, James Gennaro, hopes to end Padavan's Senate career.

While the Democrats hold a substantial edge in enrollment in this part of eastern Queens, many observers believe Padavan will hold off the challenger. The Republican has " has been described by both sides as a hard worker who is all over his district," observed Capitol Confidential.

15th Senate District: According to Malcolm Smith, voters in this Queens district hold the fate of the State Senate in their hands. "This is the tipping point," Smith said at fund-raiser for Democratic candidate Joseph Addabbo earlier this year. "There is no race more important than this one. We should all eat, sleep and dream Joe Addabbo."

The man Addabbo is challenging, Republican-Conservative Serphin Maltese has been considered all but invincible in this Queens district, for much of the last 20 years. As recently as 2002, he won re-election with more than 90 percent of the vote. But Maltese began looking vulnerable in 2006 when little known Al Baldeo, with no official backing, came within 800 votes of beating the long-time incumbent.

This year Baldeo wants another shot, but most Democratic officials are backing term-limited City Councilmember Addabbo. Baldeo and Addabbo will face each other in the primary before the victor gets to take on Maltese, and Baldeo has said he might consider a third-party run .

Despite reports that he might follow Bruno's example and retire, Maltese said he plans to remsin in the Senate. "“I’m very happy here. I’m enthusiastic," he told The Politicker.

35th Senate District: Incumbent Democratic Sen. Andrea Stewart-Cousins does not seem to have easy races. In 2004 she challenged long-time GOP State Sen. Nicholas Spano and lost by 18 votes. She tried again in 2006 and succeeded by a not completely comfortable 1,800-vote margin.

Spano considered going for another rematch in the Yonkers district but has decided against it. In his stead, Republican Yonkers City Councilmember John Murtagh will try to end Cousins' Senate career.

43rd Senate District: This was considered about as safe as a seat in anything resembling a democracy could be -- and then Joe Bruno announced he would not seek re-election. Democrat Brian Premo had already planned to run against Bruno and expects to remain in the race. On the GOP side, Assemblymember Roy McDonald seems to be Bruno's preferred replacement for his Senate seat, although Rensselaer County Executive Kathleen Jimino had also expressed interest, the Albany Times Union reported.

As giddy as Democrats may be in the wake of some recent upsets, Bruno's home turf around Albany remains tough territory for them, according to Rochester Turning. The GOP has a big advantafge in registration, and it's likely Bruno's blessing would carry a lot of weight with voters who benefited from his largesse for the past decades.

48th Senate District: This is the area of upstate that had the Democrats smelling blood in February when Democrat Daniel Aubertine beat GOP Assemblymember Will Barclay in a special election. Republicans had held the seat representing Jefferson, Oswego and St. Lawrence counties for at least a century and had a major advantage in party enrollment. In November, Watertown attorney David Renzi will try to win back the seat -- but some observers think Aubertine's new status as the incumbent gives him an advantage.

56th Senate District: In 2004 and 2006, the Working Families Party endorsed Republican Joe Rohrbach in his successful campaigns for this seat from the Rochester area. This year, though, that party left Rohrbach to endorse another candidate, former State Sen. Rick Dollinger. The Democrats hold a hefty edge in the district but in 2006 Rohrbach, a former Democrat, beat his Democratic challenger by a margin of almost two-to-one.

61st Senate District: When incumbent Republican Mary Lou Rath announced she would not seek re-election, Democrats saw an opportunity to pick up the Erie County seat. Three Democrats are vying for the nomination: former boxer "Baby Joe" Mesi, who has been endorsed by the Working Families and Conservative parties; Erie County Legislator Michele Iannello and Town of Amherst Councilman Daniel Ward. On the Republican side, Rath endorsed Erie County Legislator Michael Ranzenhofer. Robert Newman, is also running.

Elsehwere?: Following Bruno's resignation, some observers speculated that other aging members of the Republican majority in the State Senate -- and by one count older people constitute almost half of the GOP 32 members in the body -- would follow Bruno's example.Twenty-four hours after Bruno's decision became known, however, no one had done that. Two of the members in question -- Maltese and Hugh Farley -- explicitly denied any plans to step down.

Back in the City

Two other interesting races are shaping up in the five boroughs, although they seem unlikely to have much affect on who will control the State Senate.

21st Senate District: Three Democrats are vying to represents this overwhelmingly Democratic but diverse Brooklyn district, with large numbers of black voters, many from the West Indies. The incumbent, Kevin Parker, has never had the easy time most incumbents do, although he has managed to hold on to his seat.

This year he faces a challenge from term-limited City Councilmember Kendall Stewart. Stewart originally was seen as having the backing of the Brooklyn Democratic organization, but his campaign lost steam when two of his aides were indicted in the City Council budget scandal. Stewart himself has not been charged.

More recently another term limited Council member, Simcha Felder, announced he would run too. Felder has strong backing from Bloomberg and Parker has accused him of being a Republican plant. Felder denies the charges.

25th Senate District: State Sen. Martin Connor seems an unlikely person to be facing a primary challenge. He has represented his district straddling Brooklyn and Manhattan since 1978. But in recent years, he has had to fend off challenges from fellow Democrats. This time around his opponent is Daniel Squadron, a onetime aide to Sen. Charles Schumer. Connor alleges Squadron is running to settle old scores; Squadron says he is running because Connor represents "part of the system of taking money from corporations and lobbyists and doing their bidding."

The Assembly

Barring a cataclysmic event (not that we haven't seen those in New York this year) the States Assembly will remain firmly in Democratic hands. Most incumbent Assembly members from New York seem to face a fairly easy road to another term.

One exception is on Washington Heights, where incumbent Adriano Espaillat faces a challenge from term-limited Councilmember Miguel Martinez. (See related story.) A number of politicians are seeking to fill the vacancy in the 40th District in Brooklyn, which was left vacant when Assemblymember Diane Gordon was convicted on bribery charges.

And then there's the race in Manhattan's 64th district. There Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, one of the most powerful men in the state, faces not one but two challengers. If either does well, what will that say about the power of incumbency in a year when everyone is talking about change?

Â

Stated Meeting: First Steps for Building Revisions

Moving on the first pieces of legislation since a package of proposals was introduced last week, the City Council unanimously approved a bill requiring the city publish construction fatalities on its web site and notify the state of disciplinary action against industry professionals.

At its stated meeting Thursday, the City Council also, in an unprecedented move, rejected a land use application for a 100-unit development in College Point, Queens after the area’s representative left the meeting early.

Buildings Legislation Moves Forward

A week after the package was announced, the council approved the first pieces of legislation taking aim at safety and the Department of Buildings since this year’s crane accidents.

The first (Intro 511), introduced by Councilmember Letitia James, requires the city notify the state Department of Education when industry professionals, from architects to engineers, receive disciplinary action from the Department of Buildings. The legislation passed unanimously.

While the city can fine professionals for misconduct, it is the state that issues them licenses. Upping communication, James said, will increase safety in the city.

The council also unanimously approved legislation (Intro 754) requiring the Department of Buildings post the number of accidents and fatalities that occur in the five boroughs on its web site, which would be updated monthly. The list will include the contractor, the site, the work being performed and who was given violations.

The list would include fatalities and accidents for the previous five years.

Easing Congestion

The council passed two home rule messages urging Albany to pass legislation that would increase fines for blocking intersections and allow the city to implement a bus lane camera program.

The first bill would increase fines for “blocking the box” – or the intersection – from $50 to $110 and was approved by a vote of 40 to 7. Members voting against the legislation did so, some said, because they did not see increasing fines as a deterrent.

The second bill would create a camera program for bus rapid transit lanes that would give the city the authority to fine drivers who enter bus lanes on certain routes. Fines will be given from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.

That message was approved by a vote of 40 to 7, with opponents raising questions about the use of cameras to monitor traffic violations.

Park Funding

The council unanimously approved legislation (Intro 699) requiring an annual report on the private funding of parks, which is an increasing trend.

Because private groups are increasingly taking over park funding, some advocates say parks in impoverished communities, especially in the outer boroughs, are losing out. The bill’s sponsor, Councilmember Helen Foster of the Bronx, said the reports will enable the council to see where all of the funding goes, so they can better allocate public funding.

“Not every park has a conservancy,” said Foster. “We need to have the full set of facts.”

College Point

In a surprise move, the council defeated a land use application for a 100-unit market rate development in College Point. Some attributed the proposal’s defeat to politics, because the application is in Councilmember Tony Avella’s district, who left early and has gained some enemies at the council. The measure was defeated by 25 to 20.

Members said they voted against the proposal, because it did not include affordable housing. At least a dozen members changed their votes when Avella left the meeting early. Â

What the Verizon Deal Does -- and Doesn't -- Do

Photo (cc) Eric Hauser

New York City has moved quickly to seal a deal with Verizon to offer cable service throughout the five boroughs. The Franchise and Concession Review Commission waited only four business days after one unpublicized public hearing before voting on May 27 to approve the plan. The franchise still needs final authorization from the state Public Service Commission.

The contract is 59 pages long with 74 pages of appendices, plus side agreements with the community access organizations in each borough. Verizon and the city Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications hammered out the details in 18 months of secret negotiations.

A deal of this magnitude deserves more than a passing glance from the public and our elected officials. It will determine how we watch TV, make phone calls and use the Internet in New York City for at least the next 20 years. Below is a summary of key points in the agreement.

(If you'd like to read the whole thing, you can request a copy from information technology or download it from my blog, here. For background onVerizon's fiber optic service, known as FiOS, see last month's column, "Fiber Optics: Bringing the Next Big Thing to New York.")

What Verizon Will Do

The Cable Franchise Agreement between New York City and Verizon New York requires that Verizon's fiber optic network cover the entire city by June3, 2014. It sets targets along the way, giving the company more time to serve apartment buildings because of the challenges of running the wires in them. (All dates refer to December 31 of the year indicated, except for 2014, which refers to June 30.)

Under the terms of the agreement, Verizon promises to build a fiber-to-the-premises (FTTP) network, the gold standard of modern telecommunications that brings the highest capacity wires right up to every doorstep. Even if the cable companies were to replace all of their coaxial wires with fiber optics, the peer-to-peer architecture of the phone network (as opposed to the one-to-many broadcast architecture of the cable companies) makes the fiber-to-the-premises network faster, especially on upload speeds.

There are no government subsidies in this franchise agreement. Verizon will pay for the upgrade to its copper network and recoup all costs from subscribers. Other cities are considering investing hundreds of millions of dollars in a similar fiber network. The advantage of New York's arrangement is that it saves the city money. On the other hand, the network will be Verizon's alone. The other cities would have an open access network, allowing any number of companies to compete to offer services.

Verizon is paying the maximum franchise fee of 5 percent of gross revenue in exchange for use of the city's streets and other areas, usually referred to as rights-of-way. The network will be citywide, marking the first time a single provider will offer cable service to all city residents. Time Warner and Cablevision currently divide the city between them.

Once Verizon's network is complete, consumers will have two choices for cable service: their current cable provider and Verizon. Residents of most other major cities still have only one choice. A duopoly is not true competition, but it's an improvement from a monopoly.

The buildout schedule for the new service is actually pretty fast. A lot of people have criticized the uneven pace of deployment. Staten Island and Manhattan will be complete long before Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. (See chart, below.) However, this is more of a reflection of how quickly the network will cover those two boroughs, than of excessive slowness in the other three.

On the other hand, there are no meaningful penalties if Verizon ignores the buildout schedule, which, according to Bruce Kushnick's research, they have a track record of doing.

The administration has made much of the fact that the deal is for service citywide and Verizon has said it will not discriminate against poorer neighborhoods. While the company has to meet benchmarks in extending service to particular boroughs, it has full discretion about which neighborhoods to wire first within each borough. The deal explicitly allows Verizon to deploy in wealthier neighborhoods first and then extend service to other areas once it has garnered enough subscribers. These official delays are called "Checkpoint Extensions."

The franchise requires Verizon to post a $50 million performance bond, but that goes down to $35 million at the end of this year, when Queens, Brooklyn and the Bronx will have barely any service. The amount continues to drop each year. Even the starting sum of $50 million is a drop in the estimated $6-billion bucket Verizon will spend on deployment or the tens of billions the company stands to make in revenue.

There is a requirement that the households Verizon reaches cannot all be high income, but the mandate is fairly lenient. The agreement says, "The estimated median household income of all homes passed shall not be greater than the average household income of all households in New York City." But comparing a median to an average is the statistical equivalent of comparing apples to pineapples. As it's written, a household with an income of $70,000 is below the threshold. If it compared the median household income of households passed to the median of the city, rather than the average, Verizon would need to serve households with incomes of $45,000 and less in order to make the benchmark.

The Public Good

As part of its deal, Verizon negotiated a number of side agreement with the community access organizations, more commonly known as public access centers, in each borough. I have not been able to review them but am told each of the centers will receive a decent payment per subscriber per month. Of course, most Verizon subscribers will be switching from Time Warner or Cablevision, which already provide a community access charge, so this will not be a huge new source of revenue for the organizations, just a guarantee that they will not lose out.

While the funding for community access organizations is good, Verizon is not required to offer high-definition or video-on-demand services for any public, educational or government channels, though the company says it will offer this "enhanced digital platform" over time.

As part of the franchise, Verizon will pay into a Technology and Education Fund. The payment, though, is only $4 million over seven years, which comes to something like 8 cents per person per year.

The idea for this fund comes out of the city's Broadband Advisory Committee and a report from the consultant hired by the Economic Development Corporation. It represents a key part of a strategy to close the digital divide, though launching a new city agency with this money could add a new layer of bureaucracy without increasing the effectiveness of existing community technology programs. The city is going to have to augment significantly the money from Verizon if it wants to have an impact. And all of the computer skills training will be for naught if the city can't reign in broadband prices or if wealthy residents move up to high-speed fiber optics while others are left with DSL or cable modems.

Buyer Beware?

The deal lists numerous consumer protection standards and requires the completion of an annual cable consumer report card, though not until all of the cable companies have been subject to this requirement for a full calendar year. The first report card might not appear until February 2010.

The deal lowers the consumer protection standards codified in the existing franchises. Most notably, the proposed franchise would significantly reduce the established penalty for a cable company missing a scheduled installation or repair appointment. Currently, the penalty for a missed appointment - the appointment is not for a precise time, but for a four-hour window - is free installation (for an installation call) and one month's credit based on the preceding month's bill. The Verizon franchise reduces this to a $25 credit.

Verizon apparently raised this in negotiations, pushing hard for the flat amount. According to the information technology department, it then became a matter of agreeing on how much that amount would be, but it's hard to imagine how it could be lower: Did Verizon originally propose a $5 credit?

The administration says that penalties are less crucial than they once were because consumers will now have a choice of cable providers. If Verizon's customer service is unsatisfactory, people can opt for Time Warner or Cablevision. But the lower standard will be written into the competitors' franchises when they are renewed this year, immediately putting them into effect citywide, while Verizon's competition will roll out slowly and unevenly. Huge portions of the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens will have no competition and weaker protections for the next four to nine years.

The competition may also spur the providers to lock subscribers in to extended contracts with the kind of early termination fees that cell phone companies have used. The Daily News reported last month that Verizon was planning to impose a penalty of $199 on subscribers who cancel service. When Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer questioned Verizon on this issue, company officials acknowledged they might impose it on special introductory rates or on package deals like the common "triple play" of Internet, phone and cable service combined.

It costs an estimated $1,000 to $1,200 to install FiOS in a home. Once in place, fiber optics requires much less repair and upkeep than copper or coaxial wires so they are less expensive to maintain. But Verizon needs customers to keep the service for a year to recoup that installation cost. This is one of the reasons Verizon likes to pull out the old copper wires when it installs the fiber optics, since it means the customer loses the option of downgrading to the cheaper service. A company representative said, however, that its current practice in New York is to leave the copper in place unless the customer requests the wires' removal.

Other Issues

The provisions for non-English speakers are vague, simply saying that Verizon should provide service in a language spoken by a "substantial" number of its subscribers. This is of little use to potential subscribers who do not speak English, unless Verizon decides there are enough customers to make it profitable to offer services in their langue. Further, the open-ended language raises the concern that this franchise is more of a gentlemen's agreement than a service contract. The franchise could specify what languages Verizon must provide service in.

There has not been enough public disclosure. The deal was worked out behind closed doors and it seems as thought the department of information technology wants to conduct all of its oversight in private, as well. The agreement makes frequent reference to the confidentiality of information that Verizon will provide to the city, but the presumption should be on disclosure, not secrecy.

The Bottom Line

Overall, the deal is very favorable to Verizon, which, pending Public Service Commission approval, now has access to the largest cable market in the country. It permits the company to build to areas of the city in the order it wants and allows for delays if its services do not attract enough subscribers early on. There are no repercussions for further delays or for poor customer service.

New Yorkers will benefit from having a fully fiber optic network and a choice of cable TV providers. According to Consumers Union, the existence of a second choice in cable providers tends to lower prices by as much as 15 percent. But the lowered customer service standards suggest we may see the phone company sink to the level of the cable companies rather than see the cable companies rise to the level of the phone company. This deal is the beginning of the end of competition for Internet or phone service in New York. Rather than choosing among multiple providers for each service, you will choose between two packages of all of your communication needs - TV, phone, Internet.

There are certainly enough red flags in the deal to have warranted further review from the franchise review commission. Now that the arrangement seems almost certain to be approved, it will be up to the department of information technology to provide reliable oversight and report regularly to the public on how well Verizon is living up to the agreement. As part of that, the department should maintain an up-to-date buildout calendar on its Web site and release the reports that Verizon is required to file with them. The city will have to make good on the initial $4 million Technology Education Fund by finding additional money. And local consumer and public interest groups will have plenty to keep them busy in this area for years to come.

Â

Anger and Accusations Greet Budget Cuts

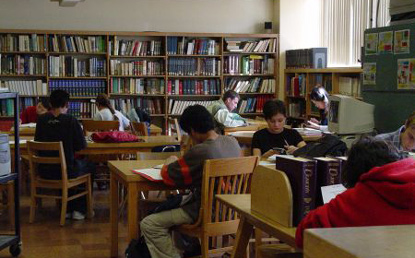

Image from Bronx High School of Science

Students at Bronx High School of Science, slated to bear some of the budget's largest cuts.

For years, the city schools have not only been immune to budget cuts. They have seen their funding increase dramatically. Now, though, that has started to change, and the controversy over whether to cut, how much and where has touched off a heated debate. A number of City Council members, including Council Speaker Christine Quinn, have indicated they will not vote for any budget that includes cuts to the classroom.

Quinn said she could not "in good faith" support a budget that cut classroom spending. Acknowledging the straitened economic picture, said, "Even in that climate, even with that reality, there are some services that have to be protected."

Councilmember Lew Fidler agreed. "There generally a sense in this council that this budget is not going to pass if there's a dime of cuts in the classroom," he said.

The money at stake represents a tiny proportion of the school system's $17.6 billion budget. But with schools still suffering from low achievement rates, advocates see any cut as unconscionable (as Mayor Michael Bloomberg himself might say) and a betrayal by the mayor of his pledge to remake the nation's largest public school system. In the last week, the debate has become even more contentious. The administration has sought to blame the state for the cuts, while state officials have blasted the city for trying to shortchange New York's poorest children and council members have accused the administration of "divisive" tactics.

Subtracting by Adding

By most measures, the cut is not exactly a cut. Overall, according to a statement by Schools Chancellor Joel Klein, funding for schools will increase by $664 million in fiscal year 2009, with $535 million coming from the state largely as a result of the settlement in the Campaign for Fiscal Equity suit over school financing. However, Klein said, basic costs for education are projected to rise by $963 million next year because of contract agreements with teachers and other education department employees, and rising fuel, energy and special education costs. This leaves the city with a $299 million gap in money for education. (The city has already reduced education spending this year from its anticipated level.)

Klein said he has identified some $200 million in cuts in what the department calls "non-school spending" -- such as the central and district administrations. That leaves almost $100 million to come out of spending for the district's approximately 1,200 schools.

Opposing the Cuts

Over the past several months, education advocates, many members of the City Council and other officials have adamantly opposed any cut in city education spending. In February the teachers union, Campaign for Fiscal Equity, the Coalition for Education Justice and other groups formed a coalition called "Keep the Promises" to fight any cuts. The coalition has staged rallies and launched an advertising campaign to press its case.

"We have been getting better for a while, and we thought there was a way to progress, and then all of the sudden there's these cuts," Alicia Cortes, the parent coordinator at Intermediate School 302 in Brooklyn told the Times. "You can't cut off people's legs and then expect them to succeed."

When the state, facing a more dire budget picture in the city, increased funding for schools, advocates focused their anger on Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Klein. At a hearing on the education budget Monday, a number of council members questioned whether the city needed to classroom spending at all . They pointed to reports (see related story) that the city could have a $4.6 billion budget surplus at the end of this fiscal year.

"Being ultraconservative is not being fiscally responsible to the children of New York City," said Councilmember Robert Jackson, who chairs the education committee.

Other members urged Klein to look outside the classroom for cuts, perhaps to the contracts budget, as Quinn suggested. John Liu offered that if money was indeed that tight, the mayor might want to take a second look at the $400 property tax rebate he sends homeowners every summer.

Sharing the Pain

Last week, Klein began offering briefings on specifically where the reductions would come from. He said the city's most prestigious schools, particularly middle and high schools, would bear the brunt of the $99 million in cuts. This would include, he said, a cut of about $955,000 at Stuyvesant High School, $852,000 at Bronx High School of Science and $133,762 as Salk School of Science, a well regarded Manhattan middle school.

The culprit according to Klein, is a state program that tries to focus some state education money on low performing schools. Known as the Contracts for Excellence, it has been a bete noire of the Bloomberg administration, which has a history of resisting any limits on its control of public school spending and programs.

If the state loosened the requirements, Klein has said, the city could cut spending at all schools by a comparatively manageable 1.4 percent, sparing any school the kind of slashing that might now take place at top schools. "I asked for discretion so that I can treat all students equitably," Klein told City Council.

To make a complicated situation even murkier, according to Klein, the city cannot simply augment Stuyvesant's budget to make up for the difference in its state funding and that of a poorly performing high school -- a process Klein called "supplantation." So, he said, if the state does not relent, the city would have to spend $400 million to avoid any reductions in individual school budgets. On the other hand, if the state relaxed its restrictions, the city would have to spend just $99 million to avoid the cuts.

To bolster his argument, Klein has said that a change in the city's school funding formula, enacted last year, already takes into account schools that have particular needs, such as large numbers of students living in poverty.

"When people say our high-needs schools are being underfunded, they don't understand that last year we took a huge step toward solving that problem," he has said.

If Klein thought this proposal would tamp down the anger over budget cuts or at least deflect it, he miscalculated -- badly. Whatever the merits of Klein's argument, it appeared to "backfire," as the Times put it. Some saw it as a bald-faced effort to provoke outrage from parents with children at elite school, who tend to be more vocal and have more political clout than parents of students at poor schools, many of whom do not speak English or understand the vagaries of New York City budget politics.

"It's a political game on the backs of the kids," Paola De Kock, president of the parent association at Stuyvesant, told the Daily News.

Several council members at the budget hearing agreed. "We have to avoid pitting the high-needs child against the low-needs child," said Mike McMahon.

Other observers, including state officials, viewed Klein's comments as a move to shift blame."What you're trying to do in my opinion is hold a gun to Albany," said Jackson. "If I was a legislator in Albany, I would be enraged that you were trying to hold me hostage."

Many of Klein's critics, including Jackson, who was an original plaintiff in the Campaign for Fiscal Equity suit, noted that the suit was intended to help poorly performing schools or those with many students who are poor, do not speak English or require special education classes. "The lowest performing schools need more, not less," Jackson said.

"The funds are to bring all the schools to equal standing," said Councilmember Melissa Mark Viverito. Using it to plug holes in the budget from Bloomberg's cuts, she continued, "is something we would not support because that is not the intent of the funds…. I would ask the state not to consider or entertain that."

She probably does not have to worry. In public comments last week, various state officials said they would block any effort to relax controls on the money.

"There's no chance we're even going to consider what the chancellor is talking about," State Sen. Kevin Parker of Brooklyn told the Post.

State Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver issued a statement saying, "If the city provided the funding as promised, there would be no need to discuss budget cuts for schools around the city."

Advocacy groups endorsed that position. "Asking the state for flexibility is 'unconscionable,'" Geri Palast, president of the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, said in a statement. "The state in tough fiscal times stayed the course and kept its promise of increased funding to meet its CFE obligations. The city must do the same and not pit higher performing schools against the lower performing schools."

At least one council member cast took a more jaded view of the state government's action. Albany does not deserve any praise for increasing education money to the city, since the city pays $14 billion more in taxes than it gets back from the state, according to Peter Vallone, just about Klein's only defender at the City Council hearing. The state, Vallone said, "is like a thief taking your wallet, giving you a dollar back and saying, 'look how much I give to charity.'"

Â

The View from Fit City 3

New York City collectively gained 10 million pounds between 2002 and 2004. In those two years more than 170,000 New Yorkers became newly obese. As a city, we have a weight problem that has created a health problem -- and it's getting worse.

While a number of factors contribute to this obesity epidemic -- and to heart disease, stroke, asthma and some forms of cancer -- more and more experts attribute it, in part, to the shape of the city and the physically inactive lifestyle it has created. With this in mind, public health professionals, policy makers and designers are taking a closer look at how the built environment affects the public's health and, more importantly, ways in which they can work together so that New York City can, by its very structure, encourage physical activity.

Earlier this month, the commissioners of five city departments -- Health and Mental Hygiene, Design and Construction, Transportation, City Planning, and Parks and Recreation gathered for a conference -- called Fit-City to see what could be done. City employees, public health experts, urban planners, architect, and policy specialists packed the Center for Architecture on LaGuardia Place to discuss what has become a hot topic.

Creating Healthy Cities

The idea of using design to fight illness is not new. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, infectious disease experts banded together with planners, sanitation specialists, and urban reformers to combat tuberculosis and waste-born diseases. The structures, laws and regulations they created remain essential to New York City's infrastructure. However, as that health crises faded, so too did the unusual and productive partnership that helped curb it.

Only in recent years, with the sharp rise in obesity-related chronic illness, has the connection between the design of a place and its health reemerged in policy circles. According to Dr. James Sallis, a professor at San Diego State University and the Fit-City conference's keynote speaker, in 2000, fewer than 50 academic papers focused on the relationship between the built environment and physical activity. In 2006, more than 300 academic papers made that same connection.

That research has not simply stayed on the shelf. In recent years, public health professionals have become increasingly involved in planning, transportation, and design decisions. Interagency reports and task forces now often include representatives of the health community. The Fit-City conference itself, with its goal of "promoting physical activity through design" and a diverse roster of speakers and attendees, is testament to the growing importance of public health considerations on design and vice versa.

The Cost of Inactivity

The rates of chronic illnesses that regular physical activity can help combat, or at least reduce the risk of, like diabetes and heart disease, are skyrocketing in New York City. According to Department of Health and Mental Hygiene statistics, more than 500,000 New Yorkers have been diagnosed with diabetes, more than 1 million are obese, more than 2 million are overweight and more than half report having no physical activity or significantly less than "healthy people."

Other chronic illnesses are of great concern too. About 6 percent of New Yorkers have had an asthmatic episode in the past 12 months, and in some communities, like northern Manhattan where hospitalization rates for asthma are 21 times higher than in the least affected New York City neighborhoods, estimates of childhood asthma rates are as high as one in four. Increasingly reports link high rates of these chronic illnesses to certain patterns in the built environment, such as location of highways, traffic patterns and citing of certain facilities, such as bus garages.

Researchers have found that asthma rates and the frequency of asthma episodes are correlated with air quality, which in turn is related to proximity to high vehicular traffic. Numerous students have highlighted the high asthma rates in Washington Heights in northern Manhattan and Hunts Point in the Bronx (see related article). Both neighborhoods are flanked by highways and inundated with truck traffic.

Furthermore, studies from around the country point to the correlation between obesity and a lack of physical activity. In 2006, the Journal of the American Medical Association published "Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in the United States, 1999-2004," which found that 25 million kids are overweight or obese. That is more than one third of all children in the U.S. According to 2006 estimates by the office of the surgeon general, nearly two thirds of all adolescents do not engage in the recommended hour a day of moderate activity.

The effects of all this extend far beyond the ill individuals and their families. Asthma hospitalizations cost the city more than $240 million in 2000, and the Centers for Disease Control estimate that the obesity epidemic cost the United States $117 billion in the same year in direct medical expenses and indirect costs, including lost productivity.

Couple those numbers with the litany of studies that conclude the design of neighborhoods, schools and parks can greatly influence physical activity and it is simple to see why health professionals and planners are talking more and more about how they can help each other confront these problems.

Places to Exercise

New York City, according to many at the conference, has already taken steps to promote this collaboration. Although Mayor Michael Bloomberg's sustainability initiative PlaNYC focuses primarily on accommodating growth in the city while improving the environment, many of its goals, participants said, would also make for healthier communities.

Take for example the schoolyards to parks initiative. To help meet its aim of ensuring that every New Yorker lives within a 10-minute walk of a park, Bloomberg and Parks and Recreation Commissioner Adrian Benepe have opened 30 school playgrounds during off-school hours so they can be fully enjoyed by community members. The city plans to open 260 more schoolyard playgrounds by 2030 and claims that the program will make a space for physical activity easily available to approximately 360,000 New York children.

By all accounts, park access can play a key role in improving fitness. A 2006 study published in the journal "Pediatrics" found teenage girls reported an additional "35 minutes of physical activity per week for each park located within a half-mile from home." A national study published in the same journal concluded, "Communities with seven recreational facilities within a five mile radius had 32 percent fewer overweight teens than did communities with no facilities."

Getting People Moving

The city's efforts extend beyond recreational facilities. Health, transportation and other city agencies together are examining the ways that residents move between destinations in their neighborhoods. A review of 33 studies published in 2006 found that having walkable streets and destinations near one's home increased physical activity among children, while unsafe intersections and dangerous traffic lowered the likelihood of physical exertion. This kind of data provides backing for the long-standing Safe Routes to School program, which former Gov. Elliot Spitzer secured $32 million in federal funding for last September and the Safe Streets for Seniors initiative.

PlaNYC also aims to promote cycling as a healthy means of transportation (see related story). This will include an increase in the number of bicycle lanes on city streets, along with efforts to make indoor bike parking more available to building tenants. Legislation encouraging reasonable provisions for indoor bicycle storage has been pending for some time.

Seemingly simple moves, such as getting people to climb more stairs, could have a major impact. At Fit-City, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene premiered new signage encouraging New Yorkers to take the stairs, and David Burney, commissioner of the Department of Design and Construction, spoke of changes in building code, such as allowing the use of transparent materials for stairwell doors, that would allow architects to focus more attention to stairs and make them more appealing to use. City officials played up both the environmental and health aspects of this effort by tag-lining it "Burn Calories, Not Electricity. Take the Stairs."

The Department of Design and Construction has also been working on high performance building guidelines. The agency reports that buildings with better lighting, ventilation and design are beneficial to employee health and productivity and could potentially save employers between $2 and $5 per square foot in regained productivity and between $.87 and $1.15 per square foot in a reduction of sick days. PlaNYC, however, has little to say about improving conditions in buildings, other than those owned by the city.

A Permanent Shift?

Although the city has launched many efforts to increase physical activity and health through infrastructure and design, advocates say there is still more to do.

For one, there is sometimes a gap between the goals of PlaNYC and the administration's accompanying pronouncements and the realities of some of its policies. In his proposed budget for next year, for example, Bloomberg calls for a decrease of $17.2 million in the parks department budget (see related story). The budget also does not restore the council's playground associates initiative, which funds full-time employees to oversee the city's playgrounds.

Plans to promote fitness in design can falter as they conflict with other city priorities. To cite one case currently in the news, the city sacrificed parkland and recreational facilities in the Bronx to make way for a new Yankee Stadium. As the New York Times reported, none of the replacement parks have been completed, the efforts to create new facilities have fallen behind schedule, and the area will be without some sports fields until at least 2011. NYC Park Advocates has concluded that, if and when all the parks are built, the area will lose parkland as a result of the deal.

Even if the administration managed to follow through on all the relevant proposals in PlaNYC, Bloomberg almost certainly will leave office on Jan. 1, 2010 -- and no one can be sure what will happen then.

To avoid these and other pitfalls, some advocates would like to see changes in laws and regulations. "What we need to see is more policy-based systematic oversight and less ad hoc good-faith efforts. That's the way to make things stick," said Wiley Norvell, a spokesman for Transportation Alternatives.

This sentiment is one echoed on the national level. In "The Built Environment and Its Relationship to the Public's Health," an article from the "American Journal of Public Health," the authors write, "Law can be a potent tool in creating a built environment that is conducive to public health. Public health practitioners can best influence design decisions by intervening early in the process, when broad policies are being made about population density, land-use configurations, transportation, and other-important issues."

Certainly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in the midst of the last great union of public health professionals and urban planners, real change did not come about until legislative reforms like the New York State Tenement House Act of 1901, which set light and ventilation guidelines for tenement buildings. With such laws, health and quality of life truly started to change for the better, and the infectious disease epidemic started to taper off.

Of course, prior to the passage of effective legislative reforms a century or so ago, there were conferences, one-off attempts, progressive visionaries and failed legal maneuvers for the better part of 50 years. Judging from the passion, commitment and enthusiasm on display at Fit-City, New York City may not have that long to wait for history to repeat itself.

Graham T. Beck is the managing editor of Transportation Alternatives' StreetBeat and a freelance writer. He lives in Brooklyn. Â

A Smoother Ride for Cycling in the City

Photo (cc) Alejandro MejĂa Greene

There are at least four excellent reasons to write about biking in the city this month.

First, May is National Bike Month, which is an ideal reminder that New York is a great city for cycling. Most of the city is flat, almost all of our trips are short (according to the bike experts at Transportation Alternatives, 95 percent of our commuting, shopping and other trips are less than five miles), and the climate is pretty great for cycling much of the year.

Second, now that congestion pricing has taken its place as merely one of 127 sustainability initiatives within the broader PlaNYC, it's time to think about how cycling can improve the city's congestion situation now - and how it can help create a more sustainable transportation system in the future.

Third, this is the best time of year to ride a bike to work in New York. Daylight lasts long enough to ensure that bike commuters get home before sunset. The weather is ideal for riding, neither too hot nor too cold. And the summer smog season hasn't begun yet.

Lastly, $4 a gallon gasoline. Is there a better hedge against high gasoline prices (and yes, against future subway fare hikes and service cuts?) than riding a bike?

More people are riding bikes to work than ever before. In fact, the city's Department of Transportation estimates that commuter cycling has grown by 77 percent since 2000. A quick rush-hour walk on the Brooklyn Bridge or the Hudson River Park's bike path confirms this to even a casual observer. Still, less than 1 percent of New York's commuters get to work on a bicycle. The city hopes to double this by 2015 and to triple it by 2020.

A Plan to Increase Cycling

In its recent "Sustainable Streets" plan, the transportation department outlined its strategy to increase cycling throughout the five boroughs.

In short, the department plans to create more - and better - cycling infrastructure to make biking safer. In the short run, that includes plans to build 200 new lane-miles of bike routes by 2009 and 15 miles of protected bike lanes by 2010 (see, e.g., the Ninth Avenue Bicycle Path). So far, 90 miles have been built, so the city seems to be on track. In the long run, the department expects to complete an 1,800-mile network of bike routes.

Of course, getting to work is only half the problem. Bike commuters need to store their bikes safely once they arrive. So, the department plans to install 37 bike parking shelters and 5,000 new "CityRacks" by 2011. It will also seek legislation to expand indoor bike parking and pass zoning changes to require that builders include bicycle parking in new construction.

Arguably, even parts of the Sustainable Street program aimed at other types of transportation will help make cycling safer and more pleasurable. Creating a network of bus-rapid transit lines, for example, will help reduce congestion - and create more road space for cyclists. Better management of curb space through expanding the use of muni-meters and better parking enforcement will create a better cycling environment. Traffic calming and redesigned streets (for examples, check out Ninth Street and Lafayette Avenue) benefit cyclists as much as pedestrians. Investing in better management of road projects and improving the quality of street surfaces will make cycling a less-jarring experience in many neighborhoods. Implementing a program of weekend car-free streets and reducing car use in Central and Prospect Parks will help generate a more bike-friendly environment for cycling throughout the week.

In other words, from a cyclist's perspective, the Department of Transportation's strategic plan easily outstrips anything that has ever been proposed by a New York City agency before, and should help make New York City a more bike-friendly city.

Making a Good Plan Better

Even with all of this, though, New York will not be confused with Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Paris or Beijing anytime soon. Amsterdam has its bike lanes, Copenhagen and Helsinki have free bikes everywhere, Paris has its VĂ©lib network of 10,000 bikes for cheap rent at 750 locations around the city, and Beijing is still home to millions of bike commuters, even as car ownership soars.

There are a few ways that New York City could provide a better environment for its future bike commuters.

First, Transportation Alternatives, the city's leading advocates for pedestrians and bicyclists, believes the administration can speed up the program. Even with current rates of progress, the group believes that the city can cut traffic fatalities in half, complete the full bike network, and "traffic-calm" the key streets around schools by 2015.

Second, to really ramp up biking in the city, there needs to be an easy way for bicyclists to use the transit system. Although you can bring a bicycle onto a subway car, any rush hour commuter knows it isn't easy to do so - for cyclists or non-cyclists. You can't take a non-folding bike aboard any bus, and folding bikes are accepted on local and limited buses but not express buses. Wouldn't it be great, though, to ride an express bus into Manhattan, and then use a folding bike to get around Downtown or Midtown? Plus, unlike some other cities, our buses don't have bike racks. As for Metro-North and the Long Island Rail Road, their policies seem designed to keep bicycles off trains during the work week: No bikes during commuting hours, a permit is needed and there's a limit of four bikes per train.

Third, a European-style network of free or cheap bikes everywhere is not yet on Mayor Michael Bloomberg's to-do list. But with crime down, safety up, and bike routes everywhere, could that be part of a bike-friendly platform for the next mayor?

Happy Bike Month NYC!

Â

Can Co-ops Help Close the 'Grocery Gap'?

For months, an Associated Supermarket in Flatbush, Brooklyn, sat empty with gates pulled tight over its windows, out of business like so many supermarkets across the city. But the demise of this particular store did not mean neighborhood residents would no longer have a place to buy fresh food. Instead, the Flatbush Food Co-op, which had occupied a far smaller space down the block, has brought organic goods, healthy prepared foods and produce to the old grocery store.

The expansion into a store three times as large represents a giant step for the co-op, which started in the general manager's basement 32 years ago. But it also represents a new era for food co-ops in the city generally.

Between the Flatbush Food Co-op and the Park Slope Food Co-op, co-ops enjoy record membership levels and sales, veteran managers say. In addition, a number of co-ops are in various stages of formation from the South Bronx to North Brooklyn.

Food cooperatives vary in size, goals and organization, but are generally formed to meet the dietary needs of a given community. Members of co-ops are partial owners and have a say in how the store is run and what is sells. Often, members can trade labor for discounts on the food in the stores.

As demand for healthy and organic food grows while the number of neighborhood grocery stores declines, co-ops are increasingly viewed as a way provide for the community. But co-ops also face a number of hurdles.

The high cost of real estate and low profit margins for food retailers that have forced many supermarkets to close also make it harder for co-ops to start and survive. And the proliferation of health food stores in other parts of the city makes it harder for nearby smaller co-ops to keep their doors open.

A recent report by the Department of City Planning found that communities across the city lack access to good food - something residents of those neighborhoods have been acutely aware of for some time. The report estimated that nearly 3 million New Yorkers live in areas with high rates of diet-related diseases - such as diabetes and obesity - and limited opportunities to purchase fresh, nutritious food. This shortage has helped spur the resurgence in food cooperatives across the city.

The New Guard

"I've never seen anything like what has happened in the last three years," says Joe Holtz, the general manager of the Park Slope Food Coop.

Although there were at least a dozen co-ops in the 1970s, most died during the '80s and '90s. But in the last couple of years, at least five have been formed or are being planned, many in underserved and low-income areas.

The South Bronx Food Cooperative was initiated by Zena Nelson as "a green shopping alternative." Dedicated to "making a difference in the community by working together to provide healthy and affordable food available to all who want it," it opened last year and has about 30 members. The co-op is currently housed in a community center, but is looking into a location of its own.

Eventually, the co-op might play a role in a larger vision. The planned Via Verde project, a nearby mixed-use and mixed-income development, will include a food co-op, and the developers are considering the South Bronx Food Cooperative. Scheduled to open in 2011, the project is meant to represent a new approach to development that takes into account health, the environment, and affordability.

"The planned food co-op will fulfill the aims of affordability and sustainability in a direct and real way," says Neill Coleman, a spokesperson for the city Department of Housing Preservation and Development.

Two Fort Greene residents, DK Holland and Kathryn Zarczynski, are organizing a co-op for their neighborhood. Both are members of the Park Slope Food Co-op and think a co-op would be a good addition to the Fort Greene area, which lacks a supermarket. They have had about 50 potential members show up at each of their meetings, but are still doing outreach to understand what the community would want from a co-op.

The East New York Food Co-op opened in 2006 and has about 50 members. It was formed in order to "actively improve access to healthier, high quality, and affordable foods." But it has had some troubles getting off the ground and meeting expenses. "We're still a work in progress," says Samila Jones-Daley, the founding organizer.

Although the co-op has been open for over a year, it just recently began accepting Food Stamps. The co-op's application to accept the stamps was delayed because of confusion about its status as a non-profit, which fouled up its Food Stamps application. (For state tax purposes, co-ops are considered a non-profit, but on the federal level, they are not.) In a district where nearly half the population receives some form of government income support, accepting Food Stamps is important.

Making Co-ops Pay

Other co-ops have not been able to stay above water. In Bed-Stuy, the Kalabash Food Coop, which was housed at the 123 Community Center, recently closed for restructuring. And although the Harlem Natural Food Co-op has about 80 members lined up, it has yet to find enough grants to open its doors.

Finding money represents a challenge for many of the new co-ops. Even the Flatbush Food Co-op received some assistance with its move. The Flatbush Development Corp. used part its $20,000 Community Block Grant from the federal government to assist the co-op with the expansion.

Money continues to be an issue for the co-op. Many new and old members are excited about the extra shopping space and the wider variety of items in the co-op's new store. "I'm overwhelmed and thrilled. It's really marvelous," says Hilda Weinberg, who is 88 years old and has been a member of the food co-op since 1985. "I've seen members come and go. And now I see some coming back."

But a number of shoppers and browsers noted that the prices are too high -- far exceeding those at grocery stores -- for them to shop there for all of their needs. And many residents miss the old Associated Supermarket. John Michael Rossi, who used to live above the co-op's old store and has since moved to a different neighborhood, said he never joined the co-op because he couldn't afford to shop there regularly. "It was cheaper to shop at the Associated," the he said, adding that if the Associated had closed "when I lived here, the price of our groceries would have doubled."

The extra space will allow the co-op to buy larger orders of many items, which will lower the costs. Barry Smith, general manager of the co-op, also noted that if enough members say they are unhappy about the price of an individual item, the co-op's management team will see what they can do to lower the cost. However, he said, the board and managers do have to make sure the store can survive financially.

Filling the Grocery Gap