New York Democrats Won Big on Election Night, But Many Legislative Wins Were Razor-Thin

rally for now Senator-elect Gounardes (photo: @LizKrueger)

The slumbering Democratic midterm electorate awakened this year, in New York and around the nation, and won significant victories. Across the country, the sum of the votes of the Democrats for every House of Representatives race in the nation is 60.1 million and counting. In 2014 only 35.6 million voted Democratic.

While Democrats are celebrating their booming turnout and major wins including flipping control of the House of Representatives, there’s a big question Democrats need to ponder: can they sustain and even grow this kind of voter turnout in 2020 and hold onto many razor-thin wins of these midterms? Will the Democrats stay motivated?

First, let’s look at some key numbers nationwide and in New York:

In 2018 the Democrats have gained more than 24 million more votes for the House Democratic candidates than in 2014 (this is called the National House Popular Vote), 67% more than the past midterm election. The Republican House Popular Vote this year is 50.7 million and counting, compared to 40.1 million in 2014, a gain of an extra 10.6 million, 26% over the prior midterm. The Democrats flipped 40 seats in the 435-seat House and took the majority, and there is still one race in California uncalled, according to the Cook Political Report.

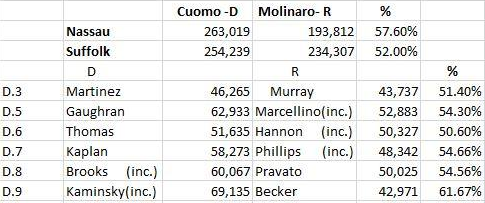

In New York, Governor Cuomo and the statewide Democratic ticket won an overwhelming victory. Compare the election night results by region on New York's gubernatorial line in 2018 with those same regional results in 2014:

The overall statewide turnout increased more than 50%, from 3.8 million in 2014 to 5.7 million this year (absentee and other paper ballots will soon be added). In New York City, the turnout surged 90%, nearly doubling, from 1 million in 2014 to 1.9 million this year.

In the New York City suburbs, the turnout rose 46% over 2014, but, more importantly for the State Senate races, the Democratic turnout in the suburbs rose 60%, from 483,000 votes in 2014 to 774,000 votes in 2018. Governor Cuomo's margin in the suburbs in 2014 was 60,000, winning 52%-45%, but this year his margin rose to 208,000 votes, and a win of 57%-41%. The dramatic improvement in the suburbs for the Democrats was a critical factor in their flipping seven Republican State Senate seats, four on Long Island and three in the Hudson Valley (they won an 8th in Brooklyn).

Long Island Wins for Democrats

A look at the results on the Governor's line and the six seats won by Democrats, including two incumbents, on Long Island:

Republicans lost four State Senate seats on Long Island and have been wiped out in Nassau County. Just four years ago they held all nine Long Island seats; when the Democrats take control in January, the Republicans will hold three. Their troubles began with the corruption conviction of former Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos; his seat was won by a Democratic Assembly member and former federal prosecutor, Todd Kaminsky, in a special election held the same day as the New York presidential primary in April 2016. Another Democrat, John Brooks, won a second Long Island Senate seat in November 2016 by 314 votes. This year Kaminsky won handily and Brooks won over 54%. In the four new victories the Democratic candidates had two 10,000-vote wins. The other two victories were close, however, one by 2,500 votes and the other by 1,400.

Hudson Valley Wins for Democrats

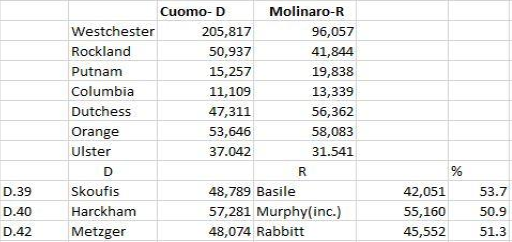

A look at the results on the Governor's line and the three Senate seats in the Hudson Valley where the Democrats won, by county in the northern suburbs of New York City and the upper Hudson Valley:

The Democrats won three Republican seats in the Hudson Valley. Democratic Assemblymember Jim Skoufis, who won his Assembly seat in 2012 at the age of 25, ran for the seat vacated by retiring Republican Bill Larkin and won by 6,700 votes, with nearly 54%. He won in Orange County by more than 4,000 votes and in Rockland County by 3,000 votes. Democrat Jen Metzger won the seat held by retiring Republican John Bonacic by a slim 2,500 votes, 51%-49%. She won Ulster County by 5,000 votes and lost Orange County by only 61 votes, 23,708 to 23, 647. Both Skoufis and Metzger likely ran ahead of Cuomo in Orange County, but his wins in Ulster and Rockland surely helped their campaigns.

Democrat Peter Harckham won the third seat in the Hudson Valley in another close race, defeating Republican incumbent Terence Murphy by 2,100 votes, 51%-49%. Harckham lost in both Putnam and Dutchess Counties, as did Cuomo, but he won solidly in Westchester, where most of the district is located, by 10,000 votes. Cuomo won Westchester County two-to-one. Democrats are celebrating their wins in the Hudson Valley, but two of the three wins were very tight.

Congressional Wins for Democrats

Below is a look at the results of the three Congressional wins in New York for the Democrats. The two upstate victories, in the 19th and 22nd Congressional districts, occurred entirely outside the New York City suburbs:

In the two upstate districts, the Democratic candidates ran ahead of Governor Cuomo, and needed to do so to win. In the 19th Congressional district, Democrat Antonio Delgado defeated incumbent Republican John Faso by over 7,500 votes. But in Ulster County he won by 16,000 votes, 43,000 to 27,000, while Cuomo's margin in Ulster was 6,000 (the Governor won there 37,000 to 31,000). Delgado also won by small margins in traditionally Republican Columbia and Dutchess County, while Cuomo lost there by slim margins. Faso defeated Delgado further north, in Rensselaer County and the Catskills, where Cuomo did not do well.

In Central New York, Democratic Assemblymember Anthony Brindisi overcame many challenges to win a very close race against incumbent Republican Claudia Tenney. Despite a 30,000 voter registration edge for the Republicans and polls showing majority approval of Trump in the district, Brindisi won by slightly more than 1%, 122,000 to 119.000. Nearly all the absentee ballots have been counted there. Brindisi won his home base in Oneida County 38,000 to 37,000, and won Broome County, where the City of Binghamton is located, by 8,000 votes. He managed to stay close to Tenney in other heavily Republican counties. Here's a comparison of the Cuomo-Molinaro race with the Brindisi-Tenney race in counties overlapping with the 22nd Congressional District. The results demonstrate how competitive Brindisi was in Republican turf.

New York City

In New York City the Democratic margins were staggering. Cuomo won 81%-15% and by 1.27 million votes. The lone New York City Republican member of Congress, Dan Donovan, was defeated. One of the only two Republican State Senators in New York City, Marty Golden, whose Brooklyn district somewhat overlapped Donovan's Congressional district, which is 70% Staten Island and 30% Brooklyn, was also defeated. Democrat Max Rose won the Brooklyn side of the Congressional district by 10,000 votes, and, amazingly, won Staten Island by 1,400 votes. The Democratic electorate on Staten Island woke up.

In the Democratic part of Staten Island, the North Shore, Rose won the Assembly district there by 16,000 votes, a margin Republicans were unable to overcome in the rest of Staten Island. Rose had more than double the vote of the Democratic candidate for the seat in 2014, 95,000 vs. 45,000. In the State Senate race, the Democratic candidate, Andrew Gounardes, defeated Senator Golden by just over 1,000 votes, another close election. Gournardes and Rose benefited from the energy and synergy of running in the somewhat overlapping sections of the Congressional and State Senate districts.

Keeping the Seats

2020 will be a big challenge for Democrats to hold the victories in New York and the nation. Many of the State Senate and Congressional wins were very close. Republicans in New York and the rest of the country will make intense efforts to recover during the presidential election, when turnout will be higher and President Trump will likely be on the ballot. Of course, Republicans have the repudiation of President Trump to blame for their losses this year. Exit polls also showed Democrats won the 18-29 age group by 35 points, a very encouraging long-term sign for Democrats. Nonetheless, the Republicans will be highly competitive in most, if not all, of these districts and the Democrats can take nothing for granted.

***

Jim Brennan was a member of the New York State Assembly for 32 years, where he chaired four committees. On Twitter @JimBrennanNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York City Shouldn’t Regulate Ride-Hailing Apps - It Should Compete With Them

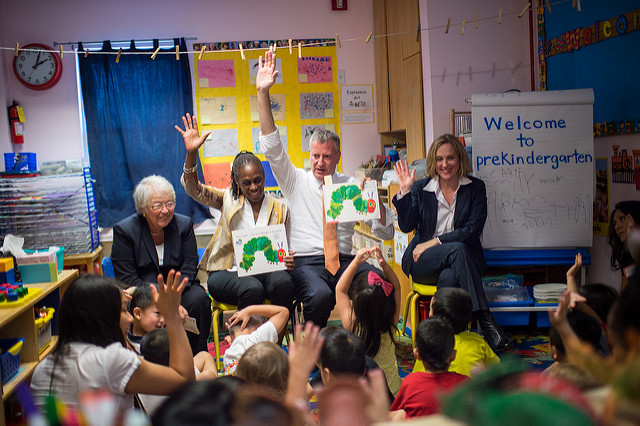

(photo: Ed Reed/Mayor's Office)

Smartphones are transforming transit in cities all over the world, and city governments are struggling to figure out how to best manage the change. If the world was looking to New York City’s recently enacted legislation affecting for-hire vehicle companies, then there will be disappointment given that, once again, the city’s political establishment decided to impose an outdated regulatory regime on innovative firms, making life harder for thousands of new taxi drivers while raising the price of rides for millions of New Yorkers and visitors to the city. The law, enacted this summer, caps the number of e-hail licenses in the city for a year and also enables the city to impose regulations on the type of compensation structures offered to drivers.

Who benefits? Politicians argue that it’s existing drivers who received their taxi registration before the one-year moratorium on new licenses was implemented, but if you think they’re the primary beneficiary then there’s a bridge in Brooklyn I’d like to sell you.

In reality, politicians got behind this legislation because they want to send a message to Silicon Valley, the startup community and their financiers: If you want access to the 8-plus million person New York City market, you’ll have to go through the local political class first, and that will cost you: in form of taxes, campaign contributions, lobbyists, and more.

True to form, the left and right have staked out their normal positions on this issue. For the left, it’s all about protecting the wages and rights of the less-than-10,000 existing drivers, even if that means higher costs for all New Yorkers and more obstacles for people who want to earn money by driving a car. For the right, it’s about protecting businesses and drivers from regulatory controls that will raise prices for consumers, even if that means facilitating the big business takeover of an industry that has been a source of wealth for independent individuals and small businesses in New York City for a century.

Like many issues involving new technology, we need to look beyond the left-wing or right-wing way to manage these technologies, and instead look to the “open source way.”

What do we want? Safe, convenient rides, with low prices for riders, high income for drivers, positive impacts on traffic, and data protection for everyone involved.

The best way to achieve these ends isn’t complex licensure regimes, quotas on new taxis, or putting more surveillance technologies in our cars or on our streets. Instead, New York City should do for its local cab industry the same thing successful industries do for themselves: standardize how information is formatted and exchanged between systems. This makes it possible for information from one app, like Uber, to be read, understood and interacted with by another app, like Lyft or Google Maps.

Making ride-hailing data more standardized and interoperable will have a number of benefits.

First, it aggregates supply and demand, which increases competition in the taxi market leading to lower prices for riders and more business for drivers.

Second, it gives riders and drivers more options, allowing them to use an app with the mission of benefiting New Yorkers instead of benefiting investors in giant tech corporations.

Third, it mitigates a threat many people fear: that Uber, Lyft, and other venture-backed ride-sharing apps are subsidizing their own cab rides to undermine the legacy taxi industry, and then once the legacy industry is dead, they’ll jack up prices. That strategy won’t work if New York City is committed to maintaining a system of its own.

The idea of establishing a “ride sharing” (or “e-hail”) standard isn’t new. It has been discussed and proposed by a number of people in New York City’s tech community for years, including Ben Kallos, a tech-aware City Council member who proposed it in a 2014 bill, and by Chris Whong, now the lead developer of NYC Planning Labs, who proposed it in a 2013 blog post.

Critics of this approach have claimed that the city doesn’t have the capacity to develop its own e-hailing systems, but that simply isn’t true. Generic apps similar to Lyft and Uber exist in hundreds of markets around the world. Even local cab companies in New York City have developed their own apps.

Creating an e-hailing system for New York City would likely involve a three-step process: (a) develop a “ride sharing data standards” body that would bring riders, drivers, city agencies, and app developers together to create specifications for how all taxi-hailing information should be formatted and exchanged; (b) develop and operate a basic, open source e-hail smartphone application that would use these data standards to, like any one of the dozens of ride-hailing apps available around the world, allow New Yorkers to request rides and drivers to fulfill those requests; and (c) create a city-administered server that not only processes information from the current city taxi app but also allows other ride-sharing apps to exchange their information with the server.

This approach would give Uber, Lyft, and other popular apps a choice: they can plug in to the city’s e-hail exchange server and share their rider and driver information with other apps - or go it alone and face the consequences of having less access to rider and driver information than their competitors.

This approach leverages the city’s considerable influence to produce a number of benefits:

By following established best practices from government digital service organizations and open source communities, this system could be produced quickly and inexpensively. And by open-sourcing an app and inviting other cities to use and modify the New York City code, we could join a small but growing community of cities around the world developing and sharing open source software (such as Madrid’s Consul project) that enables them to provide government services faster, better, cheaper, and in a more ethical manner.

The original meaning of “regulation” wasn’t the levying of taxes and fees to penalize innovation -- it was to “make regular” through the implementation of transparent business practices and the adoption of standard operating procedures. That is precisely what New York City should be doing, and it can do so by modelling best practice behavior that challenges Silicon Valley (and its New York-based counterparts) to produce better products, for lower prices, in more responsible ways, with more respect for the rights of their users.

Any municipality can throw rocks at Silicon Valley by imposing taxes and creating obstacles to market entry, but few have the capacity and scale to challenge Silicon Valley by creating innovative products. New York City has that ability. Let’s use it.

***

Devin Balkind is a technologist and nonprofit executive who works on civic technology projects in New York City. On Twitter @DevinBalkind.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Pushing the Envelope on Rent Reform in Albany 2019

(photo: Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photo Office)

This is part of AGENDA 2019, a joint Gotham Gazette-City Limits project

Find the rest of the series here

Today, New Yorkers are living in an era of mass displacement due to the skyrocketing cost of rent. This makes it absolutely imperative for rent-stabilized tenants to maintain their rights and for these rights to be extended to tenants currently living without them. We must act swiftly to implement the bold policy of universal rent-control in order to protect tenants from market forces.

Close to half of the nearly 2.2 million housing rental units that exist in New York City are rent-stabilized. Tenants living in rent-stabilized units benefit from having the right to a renewal lease once their current lease expires, plus legal limits on how much their rents can be raised annually or biannually. Additionally, rent-stabilized tenants have succession rights, granting them the right to pass their unit on to a family member living in the unit.

All of these tenant protections provided under New York state law, however, are set to expire on June 15, 2019. In the upcoming legislative session, New York state legislators will be tasked with ensuring that we pass stronger rent laws before the June deadline. With the State Senate now having the largest Democratic majority we’ve seen since 1912, state legislators have a responsibility to not only extend the rent laws to protect all New York tenants, but to also eliminate the harmful loopholes that exist in the current laws.

The Flaws with our Rent Regulated System

Although certain tenants are protected under New York’s rent-regulated system, there are loopholes that exist within the system that landlords take advantage of in order to deregulate units and to push low-income tenants out. Currently, if a rent-regulated tenant’s monthly rent reaches above $2,733.75, the landlord becomes entitled with the right to deregulate the unit and subsequently raise the tenant’s rent to any amount they see fit or simply not renew the tenant’s lease. This phenomena—known as vacancy decontrol—is responsible for the loss of at least 155,664 rent-regulated units from the years of 1994 through 2017, according to the New York City Rent Guidelines Board.

Vacancy bonuses allow landlords of rent-regulated units to increase rents up to 20 percent to incoming tenants once an apartment is made vacant. This is an amount that is seven times more than any rent increase approved by the Rent Guidelines Board – the appointed board that determines yearly increases for rent-regulated tenants – in the previous five years.

The other two loopholes that landlords take advantage of to generate more profit through the rent laws are preferential rents and major capital improvements (MCIs).

Many tenants across the city are paying preferential rents, which are below the legal margin that landlords can mandate to be paid. Why is this a flaw within the rent-regulated system considering that tenants would benefit from paying lower rent? Unfortunately, it’s been widely proven that landlords provide these lower rents while simultaneously registering a higher, fraudulent legal rent to the state. Once a tenant’s lease is up for renewal the landlord could increase the tenant’s rent to the higher, fraudulent registered amount.

Landlords also use MCIs, building-wide improvements made through the landlord’s finances, to increase rents up to 6 percent. These increases all too often surpass the 6 percent margin and are permanent increases. Landlords also game the system by fraudulently claiming improvements they don’t make or more expensive improvements than they actually make.

Vacancy bonuses, MCIs, and preferential rents are all loopholes and tactics that landlords legally and illegally utilize to raise rents and eventually deregulate a unit through vacancy decontrol.

Housing Justice for All: the Platform

Bills to repeal the loopholes in our rent-regulated system have already been written and have been stalled from passing mostly because of the Republican-led state Senate and their outgoing allies (mostly in the former Independent Democratic Conference).

A bill to end vacancy decontrol has been introduced in the past by Linda B. Rosenthal in the Assembly (A433) and by soon-to-be Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins in the Senate (S3482). Bills to eliminate vacancy bonuses have been introduced by Assembly Member Daniel J. O’ Donnell (A9815) and Senator Jose M. Serrano (S1593). Bills to prohibit landlords from adjusting the amount of preferential rent upon the renewal of a lease have been introduced by Assembly Member Steven Cymbrowitz (A6285) and Senator Liz Krueger (S6527). The offices of Senator Michael Gianaris and Assembly Member Brian Barnwell are working with the Housing Justice for All Coalition (HJFA) to write bills that would ban landlords from passing the costs of MCIs onto tenants forever (MCI costs would rather last to the end of each tenant’s lease from the moment the MCI officially took place).

HJFA is a coalition of tenant advocates, tenant unions, and housing organizations from across the state that are demanding the passage of the bills cited above. On November 15, 2018, over 700 members of the coalition showed up to downtown Manhattan on a snowy and icy night to march for these demands and then some.

HJFA is fighting to extend current protections under our rent laws to tenants that live in buildings that are five units or fewer, including 1- to 2- family homes (with exception to those where landlords reside). This concept is known as universal rent control, a policy proposal that recent gubernatorial candidate Cynthia Nixon and Lieutenant-Governor candidate Jumaane Williams, and Senator-elect Julia Salazar campaigned for.

Fifty-four counties across New York are not able to opt into having the rent-regulated protections that New York City tenants currently have, making them all vulnerable to predatory housing companies that use lax or non-existent rent regulations to push people out of their housing. HJFA is also demanding that renters across the state be granted the opportunity to bring rent controls to their communities through the expansion of the Emergency Tenant Protection Act (ETPA).

It is vitally important to point out that these demands have not yet taken the shape or form of a bill. And it is these additional demands that figures with authority, like Governor Cuomo, must deliver in 2019.

Going Beyond: Truly Delivering for Tenants

Democrats were able to take full control of state government by flipping eight Republican-held Senate seats. As of January, they will hold a majority in the Assembly and in the Senate, and the Governor’s Office. The change in the political landscape in Albany grants a window of opportunity for our leaders to strengthen our rent laws to the degree that HJFA is outlining. Unfortunately, the Democratic leadership might not be too keen on setting the bar higher and delivering universal rent control, but may rather just flirt with the idea of eliminating loopholes.

Governor Cuomo recently came out in public support of ending vacancy decontrol. Although we may all applaud this statement, the fact of the matter is that this, along with ending MCIs, preferential rents, and vacancy bonuses, should be relatively easily accomplished as soon as we enter the next legislative session.

In 2015, when the rent laws were renewed only after facing a near two-week expiration, Cuomo coined an op-ed in the Daily News and expressed his full support for passing these basic reforms. He wrote, “We must eliminate vacancy decontrol or at the very least significantly raise vacancy decontrol thresholds; further limit vacancy bonuses to ensure landlords aren't rewarded financially for schemes to force tenants out; make major capital improvements and individual apartment improvement surcharges that go away once recovered by landlords, instead of ways of artificially raising a unit's monthly rent; and make the preferential rent operate as the legal rent for the life of the tenancy. These should be foundational elements of any new rent regulation legislation.” These were the words of our governor on June 6, 2015.

Ending the various loopholes pertaining to our rent laws should be a given considering the blue wave that just occured. Leaders like Governor Cuomo with the power to push the rent regulation envelope further should not exclude from the discussion universal rent control and their support (or lack thereof) of the concept. Tenants in New York needed loopholes closed in 2015, and in 2019 the tenant movement requires protections for all tenants. Swiftly passing long-needed reform measures is important, while also tackling the challenges of today.

Ending the various loopholes pertaining to our rent laws should be a given considering the blue wave that just occured. Leaders like Governor Cuomo with the power to push the rent regulation envelope further should not exclude from the discussion universal rent control and their support (or lack thereof) of the concept. Tenants in New York needed loopholes closed in 2015, and in 2019 the tenant movement requires protections for all tenants. Swiftly passing long-needed reform measures is important, while also tackling the challenges of today.

There will be no excuse for Governor Cuomo and other leaders if the Legislature simply passes the set of reforms the governor was calling for almost three years ago. The Republican majority is no more, the opportunity for real reform is there for the taking in 2019.

And let’s be clear: universal rent control is not a radical idea. In response to high inflation rates in 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt instituted Federal Rent Control through the Emergency Price Control Act (EPCA), which allowed for “a universal, nationwide price regulatory system.” By 1950, we had 2.5 million units that were rent-regulated in New York, more than double the stock we have today.

New York City today faces an affordability crisis that it has not seen since the Great Depression and 89,000 people across the state live in homeless shelters, while tens of thousands of children sleep in insecure housing. Communities like Williamsburg, Brooklyn has seen over a quarter of their communities of color displaced. So-called economic development projects like bringing Amazon to Queens will only exacerbate the city’s affordability crisis, though stronger rent regulations would help stem the tide.

As Governor Cuomo wrote in 2015, “the crisis of affordability is back with a vengeance,” and it will continue unless we boldly act to provide protections for all of our tenants. Our task is simple and it requires the moral courage from our elected officials to stand up to real estate interests. We must prove to tenants that at a time when we have a corporate politician leading us awry in the White House that we don’t need a corporate Democrat doing so in Albany as well.

In 2019, there is no room for political posturing. We must act to not just end the loopholes within our current rent laws but also to extend protections to all renters. We must finally deliver for the largest constituency in New York, the tenant-renter constituency.

This is part of AGENDA 2019, a joint Gotham Gazette-City Limits project

Find the rest of the series here

***

Boris Santos is a former public school teacher, DSA member, and soon-to-be Chief of Staff to Senator-elect Julia Salazar.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Designing Bus Routes to Attract Passengers and Reverse Declining Ridership (Part 3)

(photo: Marc A. Hermann/MTA)

The first two parts of this series discussed the causes for bus ridership decline, the Fast Forward plan as it relates to buses and why its focus needs to be changed to reverse this decline, a plan that worked: the southwest Brooklyn changes, and MTA studies that did not achieve their desired results. Read part 1 and part 2. This third and final part discusses Brooklyn bus route changes needed now and larger conclusions about bus planning that should inform redesigns to come.

Brooklyn Bus Route Changes Needed Now

1. Routes need to be straightened so that a direct north-south bus route serves Maimonides Medical Center.

2. Service on 16th Avenue discontinued in 2010 needs to be restored using better routings serving additional areas so that it does not merely duplicate a nearby route with better service.

3. Improved east-west access is needed across Bensonhurst and Marine Park and Gerritsen Beach.

4. New shopping centers have been built in Spring Creek and in Canarsie that remain largely inaccessible by public transit. A 20-minute car trip from southern Brooklyn to Spring Creek should not take between 90 minutes and two hours by bus.

5. Service gaps on Empire Boulevard, Clarkson, and Albany Avenue require indirect travel to make simple trips accounting for the huge numbers of cabs outside Kings County Medical Center.

6. Several new routes are needed to serve JFK Airport for employees as well as visitors. A single route from Bedford Stuyvesant is grossly inadequate and converting it to SBS is not a solution.

7. Improved access is needed between Sheepshead Bay and the Rockaways, also a 20-minute trip by car, but up to a two-hour trip by bus.

8. The B44 SBS should have a branch to Kingsborough Community College when school is in session, operating non-stop from Avenue X.

9. Routing problems also exist in northern Brooklyn, but to a lesser extent. One example is the service gap caused by the elimination of the B71 on Union Street in 2010; residents and elected officials have been asking for its return in an extended fashion to also serve lower Manhattan, with no response from the MTA.

Most of these changes are described in greater detail on my website. All the proposals there with the exception of the B83 extension were rejected by the MTA in 2004, but are now under reconsideration. The fare also needs to be addressed to completely eliminate double fares by changing to a time-based fare instead of vehicle-based fare as described here.

None of these improvements will happen with the MTA's bus redesign plan unless the MTA starts thinking about its customers as people, not merely regarding them as numbers, and is less focused on operating costs.

Conclusions

1. The MTA must care more about its passengers and stop penny pinching. Service for the recent Staten Island express bus redesign, which went into effect this past summer was inadequately planned, leaving hundreds of riders stranded without enough buses and has been called a disaster by commuters. The MTA, in its concern to keep operating costs low, underestimated demand in terms of scheduling and spans of service. It has been tweaking the new system to satisfy numerous complaints.

2. Reducing operating costs by eliminating bus stops and so-called duplicative routes must not be the highest priority. Nearby routes are often serving different destinations and are not duplicative at all, but only appear so if your analysis is limited to studying a bus route map.

3. Efficiency must be increased, for example, by better integration of New York City Transit and the MTA Bus Company so that each company can use each other’s depots reducing the number of deadhead or non-revenue service miles and centralizing administrative functions such as planning and scheduling. Presently, the MTA regards non-revenue miles as more productive than miles where passengers are carried, rather than as wasted mileage. That is because service levels are planned assuming all buses run on time; labor cost savings can be achieved when partial trips to and from the depot are made without passengers and in less time. Wasteful scheduling practices whereby buses can travel up to ten miles while not in service must end.

4. Increased efficiency must not be at the expense of the passenger, like when eliminating bus stops on a massive scale. Bus stops should only be removed on a case-by-case basis, not by increasing the walking standard so that it will be necessary for some to walk up to three-quarters of a mile to or from a bus.

5. Planning should not be done by only considering able-bodied riders on good weather days. Increased walking to and from bus stops is especially burdensome on the elderly, handicapped, those with temporary health issues, and those with packages or strollers whose needs must also be considered.

6. Passengers want buses that are not overcrowded so they can board the first bus that arrives. They also want buses to arrive on time. Increasing reliability was passengers’ number one concern 40 years ago, as it is today.

7. Cooperation is needed among all relevant agencies. The MTA cannot continue to claim reliability is solely caused by traffic conditions, which is out of its control because traffic is the responsibility of DOT. What was the point of putting DOT’s commissioner on the MTA board if the two agencies will not work cooperatively? The city claimed it was not involved in the MTA’s recent decision to halt the introduction of new SBS routes until 2021. As long as the NYPD, charged with keeping bus lanes clear, continues to block the lanes with its own vehicles, and as long as the MTA bus schedules do not reflect realistic running times, and each agency blames another one, with little cooperation, reliability will not improve.

8. The emphasis must be on reducing total trip time for passengers, which is a greater passenger concern than increasing bus speeds or time spent on the bus; impacts on other traffic should not be ignored. Connections must be made easier, and routes straightened where possible.

9. Investments must be made in additional service within budget constraints, to reduce service gaps and improve passenger convenience. Shuttle routes at 30-minute scheduled intervals should not be the wave of the future in developing areas.

10. Service planning should not be designed only for existing customers. Total demand including those who use services such as Uber because the routing system is inconvenient and unreliable must be considered. If the MTA continues to assume that increased service will not result in increased ridership and revenue, and that only operating costs matter, ridership will continue to decline.

After 40 years, it is time to reflect on those 1978 southwest Brooklyn bus route changes, so the same type of successful changes that converted low-usage routes into highly-patronized routes can be duplicated. Simply providing straighter wider-spaced bus routes with fewer stops with little concern for serving destinations that are presently difficult to reach will not reverse the decline in bus ridership. Byford claims the bus route redesign will be customer driven. Let's hold him to his word. “Community consultation” does not mean that the community is merely informed of MTA changes they may not want.

This is part 3 of a 3-part series. Read part 1 and part 2.

***

Allan Rosen is former Director of Bus Planning, MTA NYC Transit. On Twitter @BrooklynBus.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Mayor and Governor Found Amazon a New Home Right Down the Street from My Shelter

(photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

The red carpet has been rolled out and Mayor de Blasio and Governor Cuomo are giddily holding open the doors: Jeff Bezos and Amazon are coming to town, for the low price of $3 billion, a helipad, and prime real estate in Queens. For years, homeless activists have pressed the mayor and governor to invest resources and political will to tackle the historic crisis of homelessness plaguing both our city and state. Instead, they partnered in selling out taxpayers and sidelining politicians to make the Amazon deal a reality.

But not everyone will accept this reality without a fight. In fact, the Amazon giveaway has been criticized by everyone from newly-elected democratic socialist Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to the corporation-friendly editorial board of the Wall Street Journal. They join homeless activists like me, city and state elected officials, and thousands of others who are concerned about responsible government and the rights of immigrants, workers, tenants, students, and many more.

I am one of 89,000 people that live in the shelter system across this state, one of the 60,000-plus that live in New York City. I am from Flatbush, but I live in a homeless shelter in Long Island City, just blocks away from where Amazon is planning to make its home. In recent months, Mayor de Blasio has faced major scrutiny for refusing to set aside 30,000 housing units in his 300,000-unit affordable housing plan to house homeless New Yorkers. I confronted him at his gym and on the radio, and others have faced him at town halls. On every occasion, he denies us the basic thing we need -- housing -- and lectures us on why his housing plan is “for every kind of New Yorker.”

“Every kind of New Yorker,” including the ones who haven’t arrived yet and the ones Amazon claims would earn an average salary of $150,000 per year.

Meanwhile, Governor Cuomo has done no better. He refuses to follow through on his own housing commitments for the homeless. In 2016, he committed $20 billion in the state budget to tackle affordable housing and homelessness -- including 20,000 units of supportive housing -- but only a tiny sliver of those resources were made available after a year of campaigning and protests.

The governor pledged to create 6,000 units of supportive housing over five years, yet two years later, 559 units were reportedly open as of August of this year. He's reduced funding for rental assistance, forced cities to shoulder the cost of shelters, and blocked legislation attempting to solve the problem with new housing assistance, like Assembly Member Andrew Hevesi’s Homes Stability Support plan.

The mayor and governor have refused to adequately help the homeless, but they’ve been quick to negotiate a deal with the richest man in the world. Take a look across the country to predict what happens next.

A Seattle county official said the city was “asleep at the switch” when Amazon arrived. By the time the giant settled in, rents had skyrocketed and homelessness soared from 8,522 people in 2017 to 12,000 during a one-night count in January 2018. In 2017, 169 people experiencing homelessness reportedly died in Seattle, and today record-numbers of people are living in cars and in tent cities. In an attempt to reverse the damage, the Seattle City Council introduced a bill to tax companies like Amazon in order to fund homelessness initiatives. The bill passed, only to then be crushed by Amazon, which refused to be taxed and threatened to stop construction in the city. This it the kind of power we are up against in New York. Our homes, neighborhoods, and our lives are on the line.

Mayor de Blasio and Governor Cuomo have long-ignored the true needs of the homeless across New York. But by bypassing democracy and giving Amazon billions in incentives and grants to move here, they are trying to erase us -- and many others -- from the map.

We won’t have it. We must remember, this is not the mayor’s city nor the governor’s city, and it’s certainly not Amazon’s city -- it is ours.

Now it is critical that we fight back against this plan and demand the future we all deserve: safe and affordable housing for all New Yorkers, quality education for our kids, a transportation system that works, strong small businesses that remain the lifeblood and culture of our city, a powerful unionized workforce that bolsters fair wages, families that are never divided, and companies that don’t profit off the imprisonment and deportation of our loved ones.

***

Nathylin Flowers Adesegun is a community leader at VOCAL-NY. On Twitter @VOCALNewYork.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Amazon Will Only Exacerbate Long Island City School Overcrowding

(photo: Rob Bennett/Mayoral Photography Office)

The plan to provide Amazon up to $3 billion in city and state tax cuts and other subsidies to site one of their new headquarters in Long Island City leaves the children who are living there in the lurch. The booming community is already severely short on school seats, a problem that Amazon’s move to the area will only exacerbate given recent trends, Department of Education projections, and the details of the Amazon deal that have been released.

The only zoned elementary school in Long Island City, PS 78, is already at 135% capacity, and more than 70 children who were zoned to the school were put on the waitlist for kindergarten last spring, while classes for numerous pre-K kids are being housed in trailers.

There are plans for two small elementary schools of about 600 seats each to be created as part of a huge 5,000-housing unit Hunters Point South development, but these schools are likely to be immediately overcrowded the day they open. There are already three sections of kindergarten students attending class in an incubation site at a nearby pre-K center, waiting to attend the first elementary school, which will not be completed until 2021.

An already-planned middle school had been proposed to be built on city-owned land as part of a mixed-use 1,000-unit project, but this area is now to be incorporated into the Amazon development. Contrary to Mayor de Blasio’s claims, the memorandum of understanding with Amazon includes no new school for the neighborhood. Instead, the MOU merely says that the company will pay for this middle school already in the city’s capital plan – but moved to another location, as yet undetermined. As Chalkbeat NY explained, “The company agreed to house a 600-seat intermediate school on or near its Long Island City campus, replacing a school that had already been planned in a residential building nearby.”

From 2006 to 2017, more than 20,000 residential units were built in Long Island City. A study found that 12,533 apartments in 41 separate developments were built in the community between 2010 and 2016 – not just the highest number in New York City, but more than any other neighborhood in the entire nation.

The housing start data recently posted by the School Construction Authority projects 20,000 residential units to be built between 2018-2024 in Queens’ District 30, which includes Long Island City. According to the DOE formula used to estimate how much school enrollment growth this will generate, there will be a need for seats for about 4,000 additional elementary and middle school students. Meanwhile, the new proposed five-year capital plan for 2020-2024 includes only 1,012 new seats for the entire district – a shortage of nearly 3,000 seats, before the impact of the Amazon deal is even considered.

Though nearly all Queens high schools are already overcrowded, there are fewer than 1,000 high school seats for the borough in the proposed five-year plan, while the housing start data alone would generate the need for about 5,000 additional high school students.

Another part of the deal includes Amazon making payments in lieu of taxes into an infrastructure fund that, starting 11 years after the deal, the New York City Economic Development Corporation (EDC) can spend on nearly any sort of use, “including but not limited to streets, sidewalks, utility relocations, environmental remediation, public open space, transportation, schools and signage,” according to the MOU.

And to add the most grievous insult to injury, the city now plans to give Amazon a large DOE office building, one that community members have been fighting to convert into much-needed schools and a community center instead. A petition, now with more than 1,500 signatures, to the mayor and local elected officials was posted last year by the Long Island City Coalition.

This is not the first time the community’s needs for schools have gone entirely ignored. In 2008, EDC re-zoned city-owned land for the Hunters Point South project without any plan to create a single new school, ignoring the thousand or so children who were likely to inhabit these new apartments. It took a concerted organizing effort of Long Island City parents and elected officials in 2015 for the city to agree to belatedly include two small schools in the plans.

We’ve seen this poor planning repeatedly, wherever new residential developments are springing up. The Amazon deal is but a particularly egregious example of how the city’s policies are driven by the interests of the real estate industry and private corporations while the educational needs of our children are too often overlooked. As many education advocates, parents and community leaders have pointed out, the school planning process in New York City is broken, resulting in more than half a million students crammed into overcrowded schools and classrooms, with the problem likely to get worse as the city’s population continues to grow.

In March 2018, the New York City Council released a report, Planning to Learn: The School Building Challenge, which documented many of the problems inherent in the city’s dysfunctional planning process. Before that, Class Size Matters released two reports, Space Crunch and Seats Gained and Lost: the Untold Story, which identified many of the same problems, showing how the city’s methodology to plan for new schools is inherently flawed and lags further and further behind the actual need.

The city has consistently underestimated the real need for public schools and to plan accordingly. The school capacity formula is aligned to excessive class sizes of 28 students per class in grades 4-8 and 30 in high school, larger than the current citywide averages, and thus would tend to push class sizes even higher in these grades.

The Department of Education’s projections also are based upon housing start data that is highly unreliable, especially the ten-year data, which estimate only a tiny number of new units to be built after the first five or six years. For example, the housing start data posted in March 2017 used to create the current five-year plan projected not a single new housing unit to be built in Brooklyn between 2020 and 2024. The housing start data used for the new proposed capital plan projects 45,000 new housing units will be built in ten school districts between 2018 and 2024, but not a single one the next three years. In District 24 in Queens -– currently, the most overcrowded district in the borough -- the data projects over 3,000 new units to be built during the first six-year period, but only 150 additional units thereafter.

Worse yet, a consideration of the need for new schools is only triggered when a proposed development is projected to increase school overcrowding by at least five percent – even in areas like Long Island City, where the schools are already severely overcrowded.

Instead, every new large-scale project should require new schools to be built where schools are already overcrowded or likely to become so as a result of new housing and/or current enrollment trends. Parent-led community education councils should be consulted in a meaningful way about the likely impact on schools each time a large-scale project or rezoning is proposed, as they know the educational landscape directly, not just community boards.

The formula for projecting enrollment should include 3-K and pre-K students and should be updated regularly with the latest Census and American Community Survey and housing data. And the need for schools should be based upon more realistic ten-year housing trends – not just five-year trends, as it usually takes far more than five years to site and build a new school.

Class Size Matters and other parent leaders are proposing these and additional critical reforms to the school planning process to the 2019 New York City Charter Revision Commission so the city’s students are not left in even worse conditions in the years to come. Meanwhile, the Amazon deal should be scotched or revamped, because, as is stands, it is yet another giveaway to a corporate giant with no consideration of the need to alleviate the overcrowded schools and classrooms under which the neighborhood’s children struggle to learn.

If New York City is to thrive and offer opportunities to all its residents, we must ensure that investment in our public schools is a top priority for all agencies, including those focused on economic development. School construction should be the first consideration in all our development goals, rather than added as an afterthought years later, when the overcrowding has become too extreme to ignore. In the end, our investment in education will provide far better financial returns than yet more public land and tax giveaways to developers and corporations.

***

Leonie Haimson is Executive Director of Class Size Matters; Sabina Omerhodzic is a Long Island City resident and a member of the Community Education Council in District 30.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Designing Bus Routes to Attract Passengers and Reverse Declining Ridership (Part 2)

(photo via NYC Department of Transportation)

This is the second part of a 3-part series. Part 1 discussed the causes for bus ridership decline, the Fast Forward Plan as it relates to buses and why its focus needs to be changed to reverse this decline. In this part: measures that have worked in the past.

The Southwest Brooklyn Changes of 1978

No other group of bus route improvements were that comprehensive. The 1978 changes also differed from others in that they were not initiated by the MTA, but by the New York City Department of City Planning (DCP). It was the only time another agency suggested bus route changes to the MTA; all other route changes originated in-house. I authored the DCP route changes and headed the study, which took four years due to the MTA throwing up roadblocks. First, MTA reps suggested we expand the study’s scope; then they claimed the scope was too large, making the changes infeasible.

In the end, about 25 percent of the proposals became reality after a lawsuit by the Natural Resources Defense Council included a provision requiring the MTA to take actions in southern Brooklyn to alter bus routes to improve air quality in Manhattan per the 1970 Clean Air Act.

DCP met with community boards before and during the study to solicit bus problems and to describe both the positives and negatives of the proposal. That approach resulted in approval by three boards with the other three boards, which were least-affected, taking a neutral position. No board objected.

By contrast, all presentations of MTA studies provide limited facts, omit the negatives, and community recommendations are only considered when massive numbers support or oppose a change. That results in opposition to all MTA bus changes. The southwest Brooklyn changes went virtually unnoticed by the media because the last citywide newspaper strike occurred in the autumn of 1978.

What the Southwest Brooklyn Changes Did Not Accomplish

As complex and successful as it was, three-quarters of the proposal was rejected. It also recommended the meandering B16 serving Fort Hamilton Parkway and 13th Avenue be split into two direct routes along each of those streets to better serve Maimonides Medical Center and make bus transferring more direct. This important traffic generator has only one east-west bus route serving it and an elevated line over a quarter-mile away. The B16 would have passed directly in front of the hospital, greatly improving accessibility.

Outdated bus routes are a problem throughout the city.

Some routes were never properly designed when they were created. According to The New York Times, when the U shaped B21 was created in 1946 (then named the 21) from the combination of two other routes, there was a protest outside Coney Island Hospital that the route did not meet the needs of the community. Yet it remained in place for over 30 years until it was discontinued as part of the 1978 southwest Brooklyn changes.

Comparison with MTA-Led Studies

Unwillingness to compromise has characterized several MTA bus studies, such as the northeast Bronx study circa 1993 that resulted in no route changes. A Staten Island study in the early 1980s resulted in only two route changes and an early 1980s Brooklyn study and early 1990s study resulted in no changes at all. That is why the 1978 study stands out for its accomplishments.

It proved that comprehensive studies can work, something the MTA refuted, because its studies failed, until a few years ago when it undertook a northeastern Queens bus study at the insistence of local elected officials. Recent support of comprehensive studies by the Bus Turnaround Coalition also led the MTA to rethink its piecemeal rerouting approach.

The DCP southwest Brooklyn study cost only $250,000. The MTA spent well over $20 million on its bus route studies and has little to show for them. Only a Bronx study in the mid-1980s and the northeast Queens study resulted in a few meaningful bus route changes. The MTA also mixes good and bad ideas in its plans with too much of a focus on reducing operating costs and too little emphasis on improving service.

Examples are a service extension in Brooklyn around 2001 to the Gateway shopping center, which was combined with a route cutback in Ridgewood in order to save a single bus. Similarly, an improvement combining service on the two portions of Ralph Avenue also was coupled with a cutback in service on St. John's Place to keep costs neutral. That created a new service gap and reduced accessibility. The approach to mix good with bad ensures opposition to MTA plans.

Unwillingness to invest in providing additional bus miles to attract new patronage has partially been the reason for ridership declines. The MTA has long-insisted that bus route changes be cost neutral with the exception of the SBS program. In recent years, service in developing neighborhoods has been addressed by the creation of shuttle routes or extensions operating every 30 minutes without consideration of the rest of the bus system; those routes have not performed well. A B67 extension caused additional routing problems by terminating a few blocks from a major transportation terminal, hindering transferring, also to save a single bus.

In other words, if you make sensible proposals that do not needlessly hurt communities and are honest with them by telling them the entire story — the positives as well as the negatives, as DCP did — they will support your plan. Conflicting and partial information, refusing to compromise as in the northeast Bronx study, and refusing to respond to questions, as with the SBS program, will result in opposition.

This is part 2 of a 3-part series. Read part 1 here. The final part discusses routing changes that are still needed in Brooklyn and what needs to be changed in the Fast Forward plan.

***

Allan Rosen is former Director of Bus Planning, MTA NYC Transit. On Twitter @BrooklynBus.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Placard Abuse is Corruption; 2019 is The Year to End It

De Blasio pledging a placard crackdown (photo: Edwin J. Torres/Mayor's Office)

This is part of AGENDA 2019, a joint Gotham Gazette-City Limits project

Find the rest of the series here

In New York City, the people are betrayed by many conspiring groups. Dishonest drivers get away with breaking laws by displaying parking placards, or “courtesy cards,” or even safety vests and handwritten notes – pretty much anything that demonstrates the right connections to the placard class. The police misuse their “discretion” to operate a favor-trading system they euphemistically refer to as “professional courtesy.” Sham oversight offices and district attorneys participate in the system, too. And the politicians spread placards around and avoid oversight to buy support.

Those who abuse the system may try to rationalize it. They might call it a job perk or a victimless crime. Nonsense. And as the city becomes denser, worsening placard corruption has more impact on safety and quality of life. It impedes emergency responses by congesting streets and sidewalks and by blocking fire hydrants and turning movements at critical locations. It fills loading zones and inflames congestion. It destroys transit service by blocking bus lanes and bus stops. It makes streets unsafe by forcing people on bicycles into traffic and blocking sight lines at intersections. It makes sidewalks uncomfortably narrow and physically destroys them.

It has even seized public park land and entire streets just to provide more free parking for the placard class. It stomps on the rights of people with disabilities who cannot use crosswalks and sidewalks or safely board buses from the curb. And when the police turn a blind eye to illegally parked vehicles, it creates a vulnerability for terrorism. NYPD Counterterrorism knows about the risk of car bombs being overlooked with a placard, but the illicit parking perks consistently prove to be a higher priority than protecting the public.

Placard corruption itself is real criminal misconduct. But we are also concerned that it is often a missed warning flag for much worse criminal activity. Internal Affairs knows, for example, that police placards are attractive for drug smuggling. Failing to maintain discipline also allows the bad apples to remain on the force until they do something heinous, rather than identifying and removing them when a pattern of misconduct emerges.

With our streets already overrun with placard corruption, Mayor de Blasio made the decision last year to hand out an extra 50,000 placards. There was immediate backlash to what appeared to be an effort to buy political support from teachers, and the mayor found himself on the defensive. To save face, he announced a fake crackdown on placard corruption.

On May 24, 2017, he stood at a press conference in the Bronx with the NYPD at his side to announce the city’s new zero tolerance policy. It was empty rhetoric. There was never any real enforcement.

Even before the press conference, it seemed clear the administration was not really serious. The previous week, the mayor's press secretary responded to one of our tweets of a traffic enforcement agent refusing to write a ticket to a vehicle with an illegal license plate cover because there was a NYPD placard on the dashboard by saying: "you tweet at me an awful lot. I read almost none of them. But from what I gather, you'll care about an event we do next week in the BX."

The "crackdown" was designed from the start to minimize any real impact. It added more staff at taxpayer expense, but did not require the tens of thousands of existing officers and enforcement agents who aggressively blanket every part of the city in a half-billion dollars in tickets every year to simply provide honest enforcement. But the lack of real enforcement turned out to be even worse than we expected.

Over the course of an entire year, a grand total of 89 vehicles were towed, according to testimony at a City Council oversight hearing (which we believe included plenty of perjury by top NYPD officials). That was with new towing capacity and 100 additional enforcement agents that we are all paying for. Eighty-nine vehicles using placards to park illegally in ‘No Standing’ zones could be towed out of Battery Park City and the Financial District in a single afternoon.

Over the course of an entire year, a grand total of 89 vehicles were towed, according to testimony at a City Council oversight hearing (which we believe included plenty of perjury by top NYPD officials). That was with new towing capacity and 100 additional enforcement agents that we are all paying for. Eighty-nine vehicles using placards to park illegally in ‘No Standing’ zones could be towed out of Battery Park City and the Financial District in a single afternoon.

Ticketing also remains elusive. We see cars parked illegally with placards all the time, and when we check their summons history with @howsmydrivingny, far too often the only tickets ever issued came from automated cameras. There is no mystery why placard perp Senator Marty Golden and his friends in the police officers union fought so hard to have safety cameras disabled (before Golden reversed course amid an unsuccessful reelection bid firestorm).

At one point, the Department of Investigations put on a good show. They rounded up a bunch of nobodies that had forged fake placards and perp walked them for the news cameras. After making headlines, their effort stopped. Meanwhile, DOI continued letting drivers with NYPD placards (including some real placards that were used fraudulently) to park illegally in front of DOI’s office. Some DOI employees continued using their own placards to get away with breaking the law, too. One particular DOI staffer was eventually forced to remove his illegal license plate cover after repeat complaints, but he never got a ticket and he is still using his placard to park illegally around City Hall.

Our twitter account has crowdsourced a tremendous amount of evidence, yet the District Attorneys pretend to know nothing. Why? Perhaps to avoid upsetting police officers, whose testimony DAs rely on; perhaps because prosecuting police officers would risk cases built on testimony from those officers. Perhaps because some of the DA’s own staff are perpetrators. After all, we routinely see DA placards on illegally parked cars, including some registered out of state that look suspiciously like insurance fraud.

Some of the perpetrators of placard corruption have fought back against accountability. They do not just close 311 complaints with false statements (a crime worse than the misconduct they are covering up), sometimes they use the contact information to harass citizens who ask for safe streets. The NYPD has resorted to unconstitutional censorship on Twitter, and it illegally withholds information in response to Freedom of Information requests. To resort to such tactics, they must feel very invested in the benefits and power their corruption provides them.

But power belongs to the people, and it is up to New Yorkers to finally put an end to the corruption by those we pay to serve our city and expect to lead it ethically. Let your precinct and elected politicians know that you are not willing to accept their corruption anymore.

This is part of AGENDA 2019, a joint Gotham Gazette-City Limits project

Find the rest of the series here

***

The authors are members of the @placardabuse team.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

NYCHA Follows the Money

NYCHA RAD announcement (photo: Ed Reed/Mayor's Office)

Had the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Congress, and various Presidents funded public housing at a level equivalent to its needs for the past two decades, NYCHA would still have problems, but not at the scale it does today. Nor would a progressive Mayor be wholeheartedly embracing private management of about one-third (62,000) of the city’s precious, low-cost, public housing units. The only way to understand why the Mayor, NYCHA leadership, and many local politicians endorse increasing the use of public-private partnerships to run NYCHA is to step back and view NYCHA’s problems through the wider angle of changing federal policy.

From the 1930s to the 1990s, NYCHA lobbied for and won federal subsidies that allowed it to build and manage public housing on a massive scale. Sadly, most other American cities used these same subsidies to create much smaller, lower-quality, worse managed, more isolated, and thus less popular systems. New Yorkers, by contrast, grew accustomed to the idea that a city would have 175,000 decent low-cost apartments thanks to Uncle Sam. NYCHA employees dutifully managed thousands of towers even under very trying conditions.

By the 1990s, however, New York stood out like a sore thumb. The federal government, responding to public housing problems nationally (such as those in Chicago), was now paying to knock down towers and complexes, encouraging privatization, and pouring more money into voucher programs (i.e. Section 8) and low-income housing tax credits. The whole federal funding system for public housing was redesigned from the ground up to emphasize private sector leadership in low-cost housing.

The towers in cities like Chicago and Baltimore, many of which were only partly occupied by this point, came down at amazing speed, replaced with vouchers and privately-run, mixed-income, medium- or low-rise neighborhoods. Few former public housing tenants were rehoused on former public housing sites; instead, they were mostly scattered into private housing thanks to voucher programs. New York, with full towers, a decent management reputation, tight housing market, and local political commitment to public housing, barely participated in these redevelopment programs.

The demise of large, high-rise, elevator buildings (and public housing more generally) in the rest of the United States was, however, terrible news for NYCHA. The loss of a national program and the urban political allies dedicated to expensive and publicly-run urban public housing led to systemic disinvestment. Even “good” federal funding years did not provide anything close to the needed funds for reinvestments and operations in New York, especially given the advancing age of most buildings. The shift in federal housing policy meant the cuts were permanent features of public housing management.

NYCHA officials were in denial for years. They thought they could "manage" their way out of the problems created by budget cuts until the federal picture improved -- as they had sometimes in the past. They were wrong. Looking back now we see that the dramatic declines in operating and capital funds led to the loss of thousands of experienced employees, deferred maintenance (i.e. mold, peeling paint, broken boilers), compliance failures, inexperienced hires, and more. NYCHA labor unions also successfully fought policy changes and efficiency measures that would have improved quality of life for residents.

When it comes to a massive housing system -- in a very expensive city -- less money inevitably meant lower quality service.

The Mayor's emerging plan for NYCHA 2.0 is an overdue acknowledgment that the federal funding landscape has permanently changed. There will never be a day or decade when NYCHA can from federal funds meet its $31.8 billion capital need, or even fully fund its operations. And while the City has made up for some shortfall over the past few years, to the tune of billions of dollars, it isn’t realistic to believe that the City will redirect tens of billions more of its own capital and operating funds (unless the courts force its hand) from other worthy causes.

Shifting 62,000 NYCHA apartments to private-sector management, as planned in the initial portion of NYCHA 2.0 that we’ve now seen, through various voucher programs, allows private companies to combine rents, voucher reimbursement, and federal tax credits with the money they can borrow as mortgages, loans, etc. They will apply these funds to renovating tens of thousands of apartments in structurally sound NYCHA buildings. They can shave labor costs by hiring new workers and investing in technology. They can take a harder line on rent collection and resident behavior.

NYCHA buildings clean up well under good private managers and new employees, as anyone who has visited the RAD Ocean Bay project can attest. By shifting so many apartments to the private section, moreover, private managers will relieve NYCHA of billions in unfunded capital needs, and of the management of most of its smaller developments, allowing remaining NYCHA staff to focus on the larger projects in its portfolio. The city, of course, will not face a massive bill for renovation. There is an undeniable political payoff as well: future problems at these complexes will no longer be a mayoral liability.

Many residents, local politicians, employees, and activists are leery of NYCHA “privatization.” Indeed, the NYCHA 2.0 plan, promised by Mayor de Blasio by the end of the year, needs to build in solid protections for current NYCHA residents, encourage non-profit participation in private management, and spell out the long-term fate of these apartments as residents come and go. Given the dominance of the private sector in federal policy, and the current balance of power in Washington, those who believe in purely public housing -- the old NYCHA -- will have difficulty developing an alternative and equally beneficial plan. The ball is in their court as the NYCHA 2.0 plan develops.

***

Nicholas Dagen Bloom, Ph.D. is a professor at New York Institute of Technology and the author of many books.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Designing Bus Routes to Attract Passengers and Reverse Declining Ridership (Part 1)

(photo: Marc A. Hermann / MTA New York City Transit)

Bus Ridership in New York City is on the decline despite innovations such as Select Bus Service (SBS). Newly appointed New York City Transit (NYCT) President Andy Byford’s Fast Forward plan will not reverse this trend unless its focus is changed to make it more passenger friendly.

The plan states (page 34) that the bus route network will be redesigned within three years “based on customer needs through a process of customer consultation and analysis of travel patterns.” NYCT will also “Rationalize bus stops in consultation with local communities and the NYC Department of Transportation to reduce travel times, including eliminating under-utilized stops and consolidating closely-spaced bus stops” (there is no definition of “closely spaced”).

There are several priorities NYCT must have in undertaking this work, and lessons that can be learned from past planning.

Warning Signs and Inclusive Planning

If the recent elimination of 25 Q22 bus stops in the Rockaways is any indication, walking distances to bus stops will be a half-mile or more in some cases. Also, those changes were opposed by the community, but implemented anyway (and there was massive confusion afterward due to inadequate notice). So, what does Byford mean that changes will involve community consultation?

Bus stop removal does not necessarily speed buses. The Q22 averaged 15 mph west of Beach 116 Street. There was no need for these buses to travel faster. Further, since the eliminated stops were very lightly used, most of them were usually skipped anyway, so no meaningful time was saved by eliminating them, but total travel time for travelers was increased due to extra walking and a greater likelihood of missing the bus. Saving a few minutes on the bus due to fewer stops is not an improvement when those minutes are instead spent walking extra to and from the bus, and it may even increase trip time.

Longer walking distances disproportionately harm the elderly, handicapped, those with temporary injuries, e.g. those on crutches, or have health issues such as sciatica which makes walking exceedingly painful. Fewer bus stops can also be categorized as a cut in service.

People carrying packages, women accompanied by small children, or lugging shopping carts, pushing baby carriages, or pulling suitcases are also not willing to walk long distances. Weather is also a factor. Most would not want to walk half a mile in a snowstorm or pouring rain to get to a bus stop. When there is a choice between the bus and train, many choose the bus because they cannot walk stairs.

Bottom line: Planning should not be done by only considering able-bodied riders on good weather days.

Why is Bus Ridership Declining?

There are many reasons. The city Comptroller says its due in part to a fractured management system. Buses are often late, slow, and otherwise unreliable and sometimes overcrowded, and some routes do not take passengers where they want to go. They often involve indirect travel and one or more transfers requiring long waits. Alternatives do exist besides driving, and bus riders are increasingly switching to them. There is walking and cycling, taxis, car services and app-based services like Uber, indirect subways, and of course the decision not to make discretionary trips.

Riders want as much direct service as possible and are willing to tolerate one bus transfer except when service is very infrequent. Two transfers usually involve an extra fare for those without unlimited passes, another system deterrent. Passes do not make sense for those who cannot afford them and those who use the system less than five days a week, such as many college students. Approximately half the passengers do not have unlimited passes. Total trip time, personal safety, and cost are the primary factors determining mode of travel. Yet the MTA does not measure total trip time. It is more concerned with time spent on the bus and increasing average bus speed. Any plan which necessitates additional transfers will fail.

How Do We Reverse the Trend 0f Declining Ridership?

We can look at what has already worked for clues.

November 12, 2018 marks the 40th anniversary of the southwest Brooklyn bus re-routings, which I designed at the Department of City Planning (DCP). We studied eight interlinked bus routes and redesigned them to improve their effectiveness.

Most notably, we proposed a new 86th Street bus route (designated as the B86) replacing four separate routes that covered different portions of the street. The old routings caused unnecessary complexity making the bus system difficult to use. Three transfers and multiple fares were required to travel between Bay Ridge to Manhattan Beach. Four or five buses were required from Bay Ridge to Brighton Beach.

Rather than using such a cumbersome bus system, mass transit travel between those neighborhoods usually involved three indirect subways via downtown Brooklyn. That was replaced by making many more one and two-bus trips possible. A portion of that proposal was accepted and the new route was designated the B1. Today, the B1 has good frequencies and is the seventh most-heavily utilized route in the borough. The routes it replaced were all moderately or lightly used with poor frequencies. Service gaps were filled and connections were vastly improved.

Redesigning the City’s Bus Routes

The Fast Forward plan to redesign the city's bus routes within three years is a necessary and monumental task. Will this redesign result in increased ridership? It is difficult to tell because few details have been released.

We know routes will be straighter, with fewer bus stops. There also will probably be fewer routes since one of the goals is to eliminate what is considered duplicative route segments. What is really duplicative? Are two routes operating on the same street serving different destinations duplicative? Is a bus on the same street as a subway duplicative or do they serve different purposes? Will eliminating one of them increase the number of transfers that are necessary to complete a trip? These questions need answers.

Successful route planning that increases ridership cannot merely be accomplished by studying a bus map and eliminating turns making routes simpler and easier to understand. Certainly, simple routes are desirable, but making them simpler can also make them less useful by increasing walking distances.

Operating costs appear to be the prime factor in determining the MTA's decision for how to restructure bus routes and bus stops. The single goal appears to be to have buses operate faster to reduce operating costs. In that regard, during the past decade, the MTA has converted many revenue miles into non-revenue miles for partial trips to and from depots because they regard non-revenue miles as more productive and efficient than miles where passengers are carried. Some buses even make entire trips not in service.

Bottom line: If the needs of the passenger are not the primary focus, the bus route redesign will fail to increase ridership and most likely will result greater ridership declines.

That is not to say that every bus stop is needed and no portions of routes can be eliminated successfully. Operating costs must of course be a consideration, but not the primary one. Improving reliability, reducing crowding, passenger total trip times, and transferring must be prime areas of focus.

Increased reliability can be accomplished by maintaining long routes but scheduling more service appropriate to the demand. This can in part be done by having many buses not operating end to end, but serving only the areas of the route with the highest ridership, more closely matching service to demand.

Shorter trips increase reliability because a delay at one end of the route will not affect all buses throughout the entire route. Merely splitting very long routes in half, as the MTA has done, greatly increases the need to transfer and reduces the amount of direct travel. It is better to split very long routes so that there is some overlap.

The personnel in charge of reliability should be adequate and dispatchers need to be properly trained. Bus schedules should also reflect realistic road conditions. Some bus operators have complained that some trips can routinely take them nearly twice the allotted schedule which means that all scheduled trips are not provided.

Creating exclusive bus lanes with little enforcement has not significantly improved bus reliability according to city Comptroller Scott Stringer’s office. These lanes have slowed down other traffic in many cases, increasing trip times for those not in buses, a factor the MTA and the Department of Transportation (DOT) have been ignoring.