Amid Crisis, A Promising Model for NYCHA

(image via NYCHA)

Recently, there has been a great deal of attention paid to the deterioration of New York City’s public housing stock and the plight of families living in New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) developments. We’ve seen a vigorous debate over how we got here, who is responsible, and who should control NYCHA going forward. While headlines surrounding NYCHA have been overwhelmingly negative, there is good news that illustrates the promise of better quality of life for NYCHA tenants.

Last week, the Citizens Housing & Planning Council (CHPC), a nonprofit civic research organization, released an interim report from a study on an innovative pilot program that began in December 2014. The pilot shifted management of six Section 8 properties located in the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Manhattan, to Triborough Preservation Partners, a joint venture between NYCHA, L+M Development Partners, and BFC Partners.

The transaction made available $80 million in new capital funds for renovations at buildings containing 874 units and introduced new property management. This money went towards new boilers and elevators; making buildings and units more energy efficient; improving landscaping and common areas; new kitchens and bathrooms inside the apartments, and providing security upgrades. Importantly, no residents were displaced as these renovations occurred.

We evaluated the impact of the changes at these sites before and during construction, comparing them with a control group of six NYCHA developments of similar size and characteristics. Research included collecting data on repair requests, resident turnover, energy use, and rent collection, interviews with property management staff, as well as a tenant survey conducted in partnership with Baruch College Survey Research.

The word “privatization” is a grenade that gets thrown a lot in discussions of NYCHA and does not appear in our study. As a research organization, we will leave it to others to characterize this pilot program. But here are the facts: NYCHA retains 50% ownership. The rental assistance is paid for by a Section 8 contract funded by the federal government. The renovations, approximately $90,000 per unit, were funded primarily using Low Income Housing Tax Credits and Tax-Exempt Bonds from the New York City Housing Development Corporation. Both NYCHA and HDC retain the right to approve or deny any proposed sale of the property.

A private property management company (C+C management) is now responsible for day-to-day operations at the site. As a result of the renovations, the new management company is currently responding to only one-fifth as many repair requests. Electricity usage has gone down, and rent collection has improved. At the same time, turnover rose and re-rental time took longer.

The tenant survey determined that Triborough residents’ ratings of their housing surpassed those in the control group in almost every measure, with residents’ ratings of their own apartments, the overall building, and elevators outpacing NYCHA residents’ ratings by at least 2:1.

Not only did we see obvious, physical improvements in conditions at building sites, we saw how the improvements impacted the day-to-day lives of tenants – in their comfort, sense of safety, and how they felt about their homes and surroundings. Tenants, many of whom felt trepidation about this approach, have seen results and can see that their fears did not come to fruition.

For instance, residents felt safer (65% in the pilot group felt very safe, compared with 37% in the control group), that day-to-day management was responsive (86% in the pilot group, compared with 55% in the control group), and that emergency repairs were addressed (73% in the pilot group, compared with 47% in the control group). And, interestingly, residents in the pilot group were almost 30 percentage points more likely to recommend their building to a friend or family member.

Our findings were only the first, encouraging step; we plan to continue to collect and review more data during the post-construction period.

NYCHA faces a number of daunting challenges, illustrated by the report that came out Monday morning detailing the $31.8 billion that NYCHA needs over the next five years to address unmet capital repairs. Tackling these challenges alone would be impossible. Tough times call for innovative thinking, and the City should be commended for creating a structure that brings in new partners and new resources that ensure affordability and a set of incentives that has significantly improved the quality of life for residents.

***

Jessica Katz is executive director of the Citizens Housing & Planning Council. On Twitter @chpcny.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Upstate Economy and The Election for Governor

Gov. Cuomo touting Upstate jobs (photo: The Governor's Office)

The health of the Upstate New York economy is a major issue in this year’s election for Governor. Two candidates in the general election, Republican Marc Molinaro, the Dutchess County Executive, and Stephanie Miner, the former mayor of Syracuse, a Democrat planning to run on an independent line, hail from Upstate, and are already in part centering their campaigns on criticisms of state government’s efforts to help the Upstate economy. Governor Andrew Cuomo’s rival in the Democratic primary, Cynthia Nixon, is also making it a point of attack.

Ironically, a federal corruption trial is underway against former SUNY Polytechnic President Alain Kaloyeros, who had been given a mission and vast resources by Cuomo to stimulate growth in the Upstate economy.

The Upstate region is very politically significant in statewide elections. Although the region is 36% of the state population, it has been between 46 and 49% of the statewide vote in the last three gubernatorial elections, 2006, 2010, and 2014. By contrast, New York City has been 27-29% of the vote in these elections despite being 43% of the population. Upstate New York is considered to encompass all of New York except New York City, Long Island, and the City’s northern suburbs, including Westchester, Rockland, and Orange Counties.

The region is also economically significant. Upstate New York’s population is 7 million, larger than 33 states, and is one-third of total employment in the state. My two previous columns on the Upstate New York economy focused on growth during the first six years of Governor Cuomo’s tenure, through 2016, and then a longer view.

The first review last fall showed that Upstate New York employment only grew 3.3% in total overall jobs between 2010 and 2016, compared to 10% growth for New York State as a whole. The comparable numbers for private sector employment growth were 5.8% for Upstate, compared to 13% growth for New York as a whole. The disparity between private sector and total growth relates to cutbacks in state spending when Governor Cuomo first took office in 2011 (the state had a $10 billion budget deficit that year), which resulted in job reductions in both state and local governments. Government reductions stabilized around 2013, but had been substantial by that time.

The New York City economy dominates employment growth in the state, with more than 70% of the total growth in employment statewide, at a pace of 16% overall and 19% private sector employment growth between 2010 and 2016.

The second column assessed the context and accuracy of a statement from Governor Cuomo addressing the difficulties posed by helping the Upstate Economy, when he described the Upstate economy as having a “bad 50 years.” My analysis showed that in fact Upstate employment growth outpaced Downstate in the 1980s, despite large manufacturing job losses that captured the public eye. The Upstate region also continued moderate growth in the 1990s after the recession early in that decade. It was really the two national recessions in the 21st century that battered the Upstate New York economy with new rounds of job losses and limited the capacity of the region to recover compared to those earlier decades. Upstate New York actually lost jobs between 2000 and 2010, compared to the recoveries that took place after recessions in the 1980s and 1990s.

As Governor Cuomo’s second term concludes, the Upstate economy is showing moderate improvement in several of its major metropolitan regions, which comprise a majority of the employment base. However, a number of metro regions that encompass the smaller cities continue to struggle. Below are tables breaking down growth in the 12 Upstate metropolitan areas, which comprise five-sixths of the employment base. Non-metro areas make up the rest.

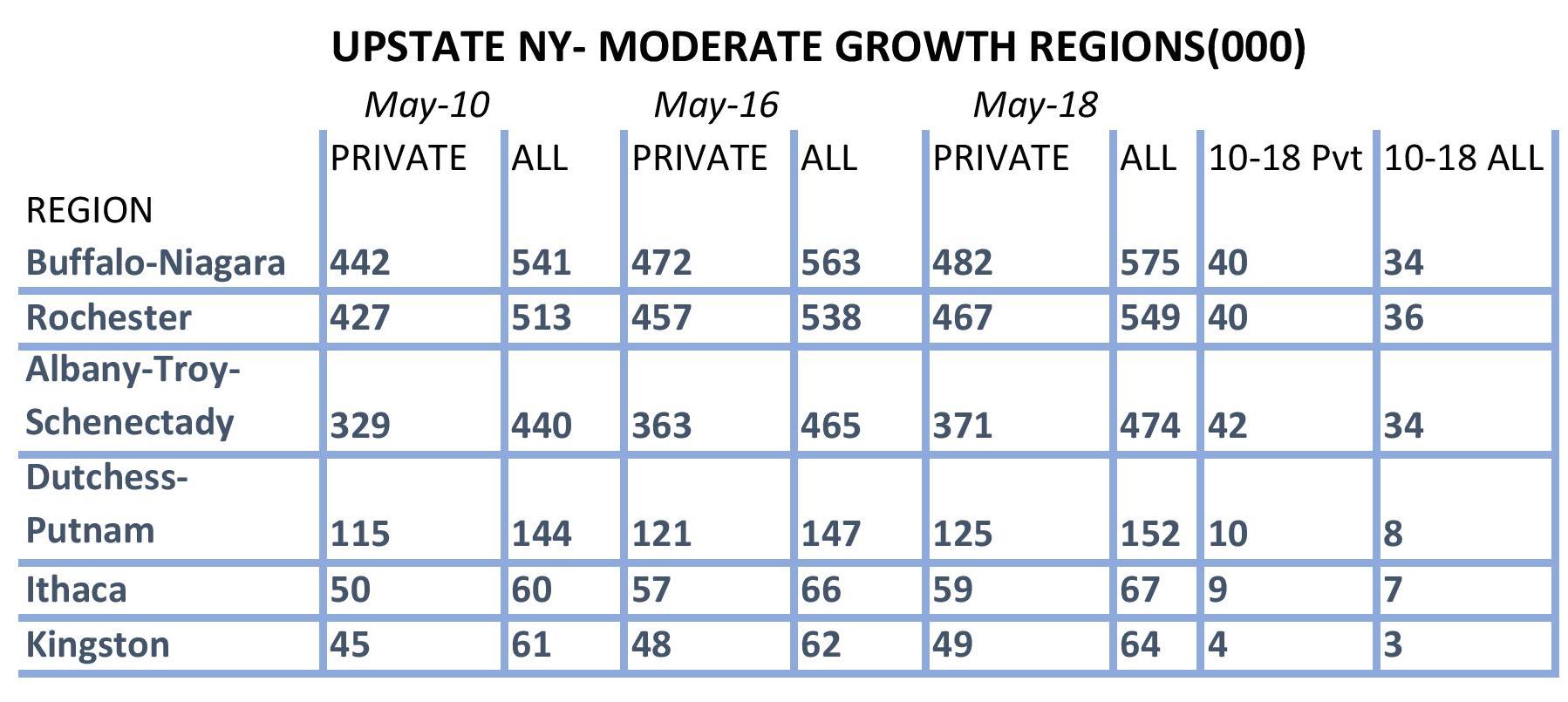

The first table shows six moderately growing metro areas (data from the New York State Labor Department):

Upstate’s three largest metropolitan regions, the Buffalo-Niagara area, the Rochester area, and the Albany metro area, achieved 9-13% private sector employment growth in the eight years from May 2010 to May 2018. Dutchess-Putnam and Kingston had similar 9% private sector growth over the period, and Ithaca is the fastest-growing metro area Upstate. The six metro areas are nearly 60% of the 3 million job employment base and in these areas private sector jobs have been growing at more than 1% a year -- not as good as Downstate New York or the nation, but sustained improvement.

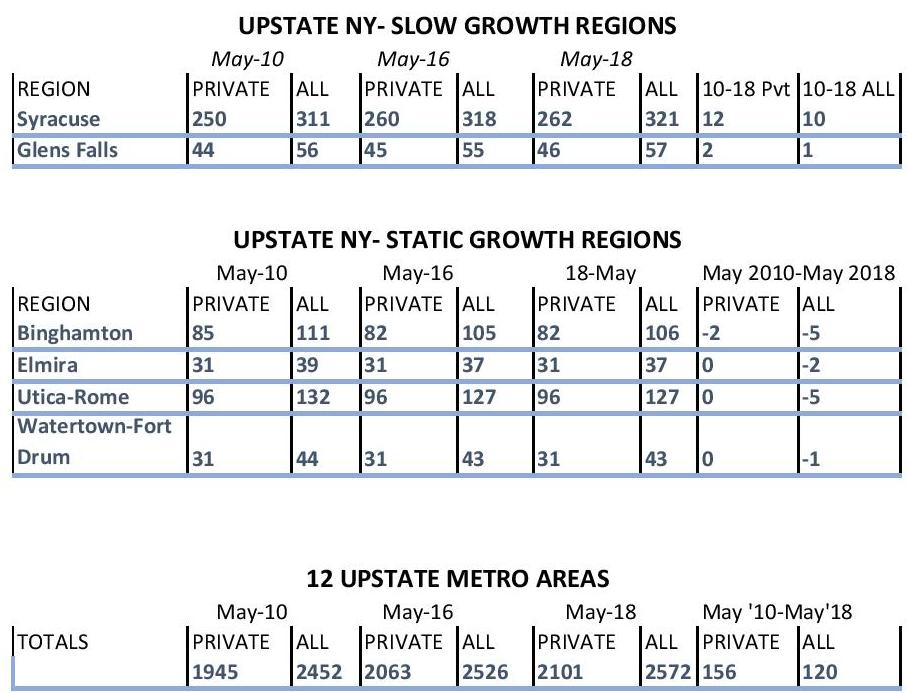

The next two tables show data for two slow-growth regions, four static/no-growth metro areas, and the third sums up the data for the 12 Upstate metro areas.

The Syracuse and Glens Falls metro areas were placed in a slow-growth category -- they achieved 4-5% private sector growth over eight years (even slower once the public sector jobs are included). There are four Upstate metro areas -- Binghamton, Elmira, Utica-Rome, and Watertown-Fort Drum -- where no private sector growth is occurring. These four areas are about 10% of the employment base of Upstate New York.

The number of jobs in non-metro areas of Upstate New York is about 500,000, about 16% of the employment base. Consistent data over the eight-year period for non-metro areas is difficult to elicit. Labor Department press releases that include non-metro growth don’t go back past 2015, so the best numbers from that source, from December 2013 to December 2017, showed growth of 4,000 jobs. My best estimation is that non-metro areas are in the slow growth category.

This portrait does not attempt to correlate direct state government investments, frequently in partnership with private companies, to create or preserve jobs, or the general allocation of state government resources, with these trends. The employment numbers are just the general trends -- and Upstate New York’s problems include population loss in some areas, like Central New York and the Southern Tier, where five of the six metro areas with slow or static growth are located. State government can also be making investments in jobs that are worthwhile individually in areas of population loss, but which do not show up in the aggregate data. Over the past seven years state government also embarked upon a broad general policy of making the state economy more competitive by cutting personal income, corporate income, and property taxes.

Empire State Development, state government’s economic development arm, finally produced a comprehensive report on its activities this year (mandated by law), and it does contain much information. Watchdogs criticized it for lacking metrics, meaning measurements of the effectiveness of the state’s investments against some set of standards. The accountability and effectiveness of the state’s resource-allocation remain the subject of another future column.

Governor Cuomo was right to say that helping an economy battered repeatedly by job losses before his tenure began is a major challenge, even if it wasn’t accurate to suggest that there was a 50-year downward path. Efforts to grow the Upstate economy seem to be modestly, but not highly, successful, although state government alone cannot determine economic destiny. How to frame this modest success in an election won’t be easy.

***

Jim Brennan was a member of the New York State Assembly for 32 years, where he chaired four committees. On Twitter @JimBrennanNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Making the Libertarian Party Viable in New York City

(photo: Benjamin Kanter/Mayoral Photo Office)

New Yorkers are constantly complaining about the two-party political system. Democratic domination of New York City politics means Democratic primary elections are more impactful than general elections. Republican domination of the national political system means New Yorkers’ progressive cultural values are rarely reflected in national politics. At the state level, Democrats and Republicans seem to have a stable alliance built on maintaining one of the most corrupt state governments in the country.

Clearly the two largest political parties aren’t working for us, so what about the third: the Libertarian Party, which is has over 500,000 members nationwide? The Libertarian Party is more than twice the size of the fourth largest party, the Green Party, and more than 10 times the size the Democratic Socialists of America. Around 20% of Americans self-identify as “libertarian.”

The strength of the National Libertarian Party and the popularity of libertarian sentiment is not reflected in New York politics, where the Libertarian Party has failed to achieve official party status, which requires getting 50,000 votes for its gubernatorial candidate. While it’s likely that Larry Sharpe’s gubernatorial campaign will earn the New York Libertarian Party official status this election cycle, the size of party in New York City will still be miniscule, at around 100 dues-paying members (which is approximately .01 percent of self-identified libertarians).

The lack of Libertarians in New York City presents New Yorkers with a massive opportunity: to build a new local political party that can have instant national reach, national operational infrastructure, and a rapidly growing base of support in increasingly relevant western battleground states. This party wouldn’t and shouldn’t look like Libertarian parties in suburban and rural communities but something new: culturally progressive with a can-do, data-driven, startup-style, open-source attitude towards solving our city’s biggest problems. If the rural Libertarians think we’re not “real” Libertarians, then they can move to New York City and defeat us in county elections.

I don’t say this as an outsider, but as the chair of the Brooklyn Libertarian Party and the 2017 Libertarian candidate for New York City Public Advocate who earned more votes than any other Libertarian candidate in that city election cycle.

My plan for a relevant Libertarian Party in New York City rests on three concepts: social tolerance, open and participatory governance, and municipalism.

Each of these concepts is consistent with National Libertarian Party ideology and with the interests of urban voters. If we can fuse the two together, we can create a new political coalition to challenge the authoritarianism coming out of Washington, D.C. and the corruption pervading our two party system.

Social Tolerance

Many people think that libertarian culture and big city culture are at odds because libertarianism is so often framed as a philosophy rooted in rugged self-reliance and individual autonomy, but that’s mostly myth. In reality, libertarians are much more interested in well-functioning markets and how complex, interdependent systems produce so much abundance. If you don’t believe me, read “I, Pencil.”

New Yorkers know better than anyone that people can successfully organize themselves through market activity because that’s how our lives are possible. We rely on complex systems for everything: food, water, transit, employment. Yes, that means we also rely on government-produced systems, and that’s fine because the “big city libertarianism” I’m arguing for respects regional autonomy. More on that later.

The single, unifying, core principle of libertarianism is that individuals should be free to do as they please as long as they don’t harm others. Sometimes this is called the non-aggression principle. Other times it’s referred to as just plain old “tolerance and acceptance.” New Yorkers embody this spirit more than any other place I’ve been in America. We love diversity and it’s myriad of benefits. We also can tolerate crowded, sweaty trains filled with strangers from all over world, and we’re constantly teaching visitors and new residents to do the same. That’s what becoming a New Yorker is all about: learning tolerance for (and even love of) diverse lifestyles, races, genders, ethnicities, cultures, philosophies, religions, et al, -- because if we don’t have it our cities simply couldn’t function.

Everyone is tolerant when it’s popular, but people are surprised to learn that, at a national level, the Libertarian Party has walked the walk: nominating the first female presidential candidate in the 1970s, supporting gay rights in the 1980s, leading the fight against the drug war and mass incarceration in the 1990s, and opposing the war in Iraq in the 2000s, Obama’s drone wars in the 2010s, and Trump immigration policies today. The New York City Libertarians can and should lead on issues of mass incarceration and police militarization, and offer something no political party has yet -- a powerful solution: ending the drug war.

Open and Participatory Governance

Our political and governmental operating systems are outdated, and need to be redeveloped for the era of the internet. Both the Democrats and the Republicans are too invested in the old system to be able to produce any substantial reforms. If we look around globally, we’ll find that some of the most aggressive and successful reforms came from the Occupy-style movements that spread throughout the world around 2010-2014. While Occupy was framed as a leftist movement in the United States, in other places it was much more obviously an anti-corruption movement that used anarchist organizing principles. In many places alumni of these movements have taken power.

Examples include Madrid, where movement activists won elections and embedded themselves in the city government and implemented an ambitious e-governance system that enables the public to control the legislature through a direct-democracy style app. Another example is in Taiwan, where activists took over the national parliament for a month during the “Sunflower” movement, won concessions from the government, and have implemented a nationwide participatory democracy program that is the envy of the world.

What these movements have shown is that there are solutions to the question of democracy: but those solutions will destroy the politics of patronage, where politicians acquire resources from taxpayers and distribute them to their constituents, and instead require a politics of participation, where politicians use technology to convene stakeholders, determine public sentiment and then perform the will of the people, even if that means suppressing their own opinions and interests. That’s a different job description for which many existing politicians would not apply.

The other major trend in internet-enabled government is the spread of “digital services organizations” and their uniquely effective method of bureaucracy reform. By using open source technologies, lean development principles, service design methodologies and other “startup-style” tools, DSOs are implementing technical systems that will, ultimately, radically transform how government is administered: reduce the need for certain types of skill sets, automating processes and making services faster, better, and cheaper.

The political establishment and agency bureaucracies have been extremely hesitant to resource these DSOs because their work is shifting power from closed bureaucracies to open systems. As such, neither establishment party can give DSOs the support they deserve. But Libertarians can! We want government to operate faster, better and cheaper -- and if that means government workers lose their jobs in the process, that’s fine. Give them a universal basic income and let's move on.

Municipalism

Municipalism

With Trump as president, many city residents have awoken to the fact that there are many layers of government -- and these various layers don’t always agree or collaborate with each other. They’re realizing that they’d much prefer a structure where the federal government has less power and municipal governments have a lot more. This “municipalism” is entirely consistent with libertarianism for two reasons. First, it localizes power and decreases the number of people each politician represents, making politicians and government more accountable. Second, it reduces the size and scope of the federal government, which is something every Libertarian supports.

By advocating at the national level for more local control, we align ourselves with a political program that spans the nation: urban and rural, progressive and conservative. Local control shouldn’t simply mean more policies are determined at local levels (although this is obviously a part of it), but should result in restructuring the tax system to shift the destination of tax revenue from the federal government to state and local governments.

I call this “flipping the pyramid.”

Currently, the federal government gets most of the tax money, then states, and lastly municipalities. This status quo should be flipped on its head so that the federal government receives the least amount of tax revenue, allowing states and local governments to gain significantly more.

In circumstances where rural and suburban communities don’t want or need big local governments, they will pay significantly lower taxes. Meanwhile, people in cities who do want lots of government services can increase their local taxes to pay for those services, without increasing the total amount of taxes they pay. Don’t want to pay taxes? Leave the city! This act of voting with one's feet is the oldest type of democracy, and the idea that people should actually get up and move from places that don’t share their values to places that do should be embraced (and maybe even subsidized).

We’ve seen what happens when we try a “one-size-fits all” model of federal policy: Washington, D.C. has been gridlocked for over a decade, the culture war is nastier than ever, Donald Trump is president, and it seems only the mega-rich are getting what they want from the political process. Instead, let’s allow for the “regional differentiation” that will naturally arise when localities have more power to determine their overall tax rate.

Maybe some cities will become hotbeds of socialist policy, and some rural communities will devolve into total anarchy. While that might sound drastic or raise the spectre of places becoming truly inhospitable to certain types of people in ways that they currently are not, we should recognize that (a) this process is already well underway for middle and upper class people who can afford to move, (b) our nation’s structural resistance to regional differentiation has led to our current political climate and (c) this approach will encourage and incentivize politically-minded people to shift their attention from the national political circus and get involved in local and state politics.

I am not advocating for the federal government to stop performing any of its constitutionally mandated or critical functions such as upholding the civil and human rights of U.S. citizens, investigating corruption of state and local officials, regulating interstate commerce, helping with disaster relief, and organizing national defense.

Rather, I’m advocating for a visioning process where we redraw the appropriate scope of local, city, regional, state, and federal powers.

While working to implement this new vision, we should also be investing our time and resources into upgrading the capacities of local, state, and regional governments so they’ll be able to absorb new responsibilities. Anyone involved with local politics knows that it can be just as corrupt as national politics, if not more so. That’s why our strategy must also include a movement to transform local governments into open, transparent and participatory institutions that good people want to lead. We can have that battle on our home turf instead of D.C.

New Yorkers, and urban residents throughout the country, deserve a culturally progressive, entrepreneur-friendly, open-source political party, and the Libertarian Party can be just that. There are no Libertarians in New York City interested in stopping us. I’m the chair of the Brooklyn Party, we’re collaborating actively with the Manhattan Party, and this weekend we’ll be taking our plan to the Libertarian National Convention in New Orleans to find allies and develop a more nuanced understanding of potential opposition to our plans.

In politics, opportunities can come from where you least expect them: maybe that’s the Libertarian Party in America’s big cities. Come find out by attending our monthly meeting in Brooklyn and the meetings of other chapters around the city.

***

Devin Balkind is the chair of the Brooklyn Libertarian Party. He was the 2017 Libertarian candidate for Public Advocate. On Twitter @DevinBalkind.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.