New York Workers Need a Raise

All New Yorkers have had to brave record low temperatures, wind, snow, sleet and rain this winter. But for Joaquim Gonzalez and thousands of other delivery people throughout New York City the past several weeks have been particularly harsh. They have had to battle the cold, slush and ice for between seven and ten hours a day, six or seven days each week. And no matter how much Gonzalez works, he still cannot get ahead.

All New Yorkers have had to brave record low temperatures, wind, snow, sleet and rain this winter. But for Joaquim Gonzalez and thousands of other delivery people throughout New York City the past several weeks have been particularly harsh. They have had to battle the cold, slush and ice for between seven and ten hours a day, six or seven days each week. And no matter how much Gonzalez works, he still cannot get ahead.

He earns the minimum wage for tipped workers: $3.30 an hour. (Workers who do not have the opportunity for tips must be paid at least $5.15.) That means eight hours of biking around snowy, crowded Manhattan streets guarantees him a mere $26.40. Sometimes he lucks out and gets a few good tips. Other times he doesn't. Last month, Gonzalez rode his bicycle more than 70 blocks in the snow for a 50-cent tip. After paying for rent, food, subway, clothes, medicine, and maintenance of his bicycle, Gonzalez is left with almost nothing.

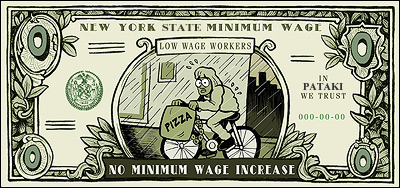

Gonzalez, like other minimum wage workers throughout New York State, is getting a raw deal. Unlike a growing number of states, New York has failed to take action to fix the problem of a stagnant and inadequate federal minimum wage by increasing the state minimum wage.

Since 1968, the purchasing power of the federal minimum wage has fallen by 40 percent. Throughout the 1960s and 70s, a full-time, year-round worker earning minimum wage could keep a family of three above the poverty line. Today, a full-time, year-round worker earning minimum wage can barely get his or her family three quarters of the way out of poverty.

Inflation has eroded the value of the dollar, and the minimum wage has failed to keep up. In the end, the New York State government is not all that different from the woman who tipped Gonzalez 50 cents. It is undervaluing its workers and doing the very least it can get away with.

Nationally, low-wage workers' real wages (taking inflation into account) increased by 5.5 percent between 1989 and 1999, but New York State's low-wage workers saw their real wages fall by 5.5 percent over the same period. Similarly, poverty declined in the United States during the 1990s, but it increased in New York State, as the income gap between rich and poor New Yorkers grew dramatically.

Governor George Pataki's proposed 2004-2005 executive budget does nothing to fix the problems of low-wage workers. In fact, Pataki's proposals would make the situation worse. The governor has proposed reducing food and living allowances for long-term welfare recipients, even though inflation continues to decimate the value of New York State's welfare grant.

Scapegoating the poorest of the poor, though, is nothing new. What is remarkable is that Governor Pataki's budget fails to reward work in any meaningful way. In fact, he has proposed a reduction in the amount of earned income that working welfare recipients can keep before losing benefits, thereby creating a disincentive to work. Additionally, his continued failure to increase New York State's minimum wage to keep up with inflation, and keep it pegged to inflation in the future, punishes hard-working New Yorkers.

New York is full of people who face rough labor conditions and the daily indignity of struggling to survive. Their treatment affects all of us. Poverty wages for workers translates into fewer consumers for business. When under-paid workers get sick, the government -- in other words, the taxpayer -- gets stuck with the bill.

New York's neighbors in Connecticut and Massachusetts have already raised their minimum wages to $6.90 and $6.75 per hour respectively, and neither state has experienced job losses as a result. Moreover, research done in California suggests that a higher minimum wage has important secondary benefits, such as improved health for low-wage workers and a greater likelihood that their children will graduate from high school.

It is high time for New York to join the growing number of states and the District of Columbia that have raised the minimum wage above the federal minimum of $5.15 per hour. Governor Pataki should support legislation currently pending in the State Assembly that would strengthen enforcement of minimum wage violations and raise the minimum wage by almost $2. This legislation would directly benefit more than 500,000 New Yorkers, and indirectly benefit many more, while saving the state money and giving the economy a boost. Joaquim Gonzalez, like all of New York State's minimum wage workers, deserves a raise.

Andrew Friedman is a senior fellow of the Drum Major Institute for Public Policy; Fernando Ferrer, former Bronx borough president and candidate for mayor, is president of the institute.

#####

Related Story:

A Minimum Wage Increase Will Hurt Small Business and the Working Poor

by Mark Alesse and Matthew Guilbault

A Budget With No Soul

Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s $45.7 billion preliminary budget(in pdf format) for fiscal year 2005 is a bland document, with few surprises and no soul. It lays out a generally optimistic budget-balancing scenario, but lacks any vision or sense of priorities. Revenues are up more than anticipated, enough so that there should be a $1.4 billion surplus by the end of the current 2004 fiscal year in June. This is a far cry from the emergency measures — mostly much higher taxes — that marked the mayor’s November 2002 and January 2003 budget plans. Last year’s bold policies worked and created an opportunity to make a personal mark this year.

But all we get is politics. A proposed $400 property tax rebate for each of the next three years for homeowners has already improved the mayor’s popularity in polls. Yet the mayor is oblivious to the new inequities the rebate would create in an already bizarre, unfair property tax system, particularly for renters and small businesses. And there is also a political slap at the City Council: The preliminary budget has no mention of over $200 million in cuts of essential service programs created by the council and borough presidents. It’s an old Rudy Giuliani trick — keeping the council busy restoring the missing dollars — that deflects council and public attention from new and more substantive options.

The budget has no soul because it has no message. Hundreds of pages of budget documents are now easily accessible in the office of management and budget’s vastly improved Web site. But the information has no overall policy or program context. Yes, the 311-system is up and running, and, yes, there is self-congratulation in changes in education, but mostly the documents simply add up to a lot of numbers. (The release two weeks after the budget plan of the preliminary mayor’s management report(in pdf format) -- the mandated report the mayor wanted voters to eliminate through last fall’s charter-revision ballot -- repeats the pattern; lots of data and no message.)

Gains in 2004 and 2005

The city financial plan for the next four years that accompanies the preliminary budget looks a lot better today than it did last June. Some improvement in the economy (but not in new jobs) has added $765 million to projected tax revenues for this fiscal year, and other revenues pushed the total new revenues over $1 billion. This helped increase the projected surplus for this year to $1.4 billion, which the new plan uses to ease budget gaps in 2005 and 2006. The 2005 plan also includes anticipated new state actions worth $400 million and federal actions worth $300 million.

The result of the revenue enhancements and the assumed state/federal actions is that there is little need to cut services next year. The mayor in this sense continues to keep his promise to maintain service levels. In fact, the annual exercise to save money, the Program to Eliminate the Gap (PEG), is only $324 million for 2005, or about one percent of total city revenues of $30.7 billion. (Whatever happened to productivity initiatives?) And most of the $324 million in savings comes not from service cuts, but from such actions as re-estimates of federal and state revenues (higher) and of anticipated needs and expenses (lower), shifting of costs from city to other government sources, and one-time revenues.

In this positive economic and fiscal context it is unfortunate that the mayor did not acknowledge his hidden budget cuts. The council, as reported in the January 22 Daily News, has found over $200 million in cuts that are not reported in the preliminary budget. They include:

- · $12 million in library cuts

- · $11 million in cultural affairs cuts

- · $11 million in senior service cuts

- · $9 million in child care service cuts

- · $8.5 million in mental health service cuts

In addition, city funding of youth services in the 2005 budget plan totals approximately $100 million, or some $40 million less than was adopted last June for the current fiscal year. The mayor disingenuously claims that all these reductions are not “cuts” because the programs initiated by the council and borough presidents are only one-year priorities, so that they were never in the 2005 plan to begin with. Mayor Bloomberg did not invent this petty political tactic, but he has certainly made it his own.

New Jobs

Although the mayor has little interest in expressing substantive goals in the budget, there are some interesting details buried in technical sections. For instance, job-creation prospects for the next four years are modestly positive: an estimated 40,000 new jobs in 2004, 51,000 in 2005, and an average 35,000 in the subsequent three years. The good news is that, unlike previous years, the city’s job recovery is not expected to lag behind the nation’s.

The recent recession had different effects on different job sectors. In a little more than two years after 2000, for instance, the high-salary securities industry went from 200,000 to 160,000 jobs. Finance-dependent services lost 70,000 jobs in roughly the same period. But there are growth areas in health, social, and education services, which collectively added 15,000 jobs in calendar 2003, and which are projected to add 15,000 more jobs each year through 2008. The securities and finance-dependent sectors are projected to have a much more modest recovery.

Empty Office Space

The budget plan also inadvertently raises some serious questions about the mayor’s sports-stadium plans. For instance, given the strong mayoral support for the New York Jets/office development on the West Side of Manhattan and the New Jersey/Brooklyn Nets basketball arena/office space in downtown Brooklyn --projects dependent on more than 30 million square feet of new office space -- it is interesting to note that two million (of nearly five million) square feet of recently completed office space in midtown Manhattan has yet to be leased. In addition, there is an unknown quantity of “shadow space,” office space currently leased but empty, so subject to future sub-leasing and therefore further depressing the market.

Prime market vacancy rates are projected to go over 13 percent in early 2004 and remain above 10 percent through 2006. Re-building the World Trade Center office space (15 million square feet lost) adds another warning sign. How do these utopian real estate goals justify any public budget support for sports stadium plans dependent on new office space for financing?

Rebates in Cigarette and Property Taxes

The budget’s casual approach to the equity implications of bold revenue plans is evident in two areas of the new budget. One is the latest report on the results of raising the cigarette tax from eight cents to $1.50 a pack. Big success! Sales in New York City have dropped by 47 percent, to 182 million packs in 2003, but revenues have grown from $27 million to $158 million in one year, an increase of $131 million, or almost 500 percent! Of course, the cigarette tax, like the sales tax in general, is a very regressive tax.

The proposed $400 rebate to owners of 1-, 2-, and 3-family houses, condos, and co-ops will cost the city about $250 million a year in lost revenues each of the next three years (a little more than the hidden service cuts). This will for the average owner apparently wipe out the 18.5 percent property tax rate increase imposed in November 2002 (which was compounded by increased assessments). This will help hundreds of thousands of owners, but it is a crude instrument.

The Independent Budget Office has over the years issued a series of reports that underscore the inequities in the city’s property tax system. One major problem is that renters’ tax burden is in effect five times that of house owners. Another is that co-op and condo owners have a higher property tax burden than house owners.

The council has narrowed the property tax inequities between house and coop/condo owners, but as in the mayor’s rebate plan, it has not tackled the larger problem of equalizing owner and renter inequities (beyond some marginal relief for seniors). Renters, who on average earn considerably less than owners, often do not recognize they are the big losers in such narrow and inequitable “reform,” and thus apparently pose little political danger to policymakers.

The re-constituting of the city’s tax revenue base by the cigarette tax and the property tax rebate should also be seen in the context of the budget plan’s phase-out of the one major progressive tax change during the Bloomberg administration. The revenue package adopted last June included two new, progressive personal income tax brackets for (joint) households earning over $150 thousand (4.25 percent) and $500 thousand (4.45 percent). But the plan also “sunsets” those progressive rates, reducing the 4.25 percent rate in the 2004 tax year, and eliminating both rates at the end of calendar 2005.

The City Council will hold hearings on the preliminary budget shortly (see the schedule) and will presumably hold separate hearings on the preliminary mayor’s management report, which the Speaker of the Council successfully urged voters to retain in the recent charter-revision vote. Perhaps there the public will get a chance to hear what message or vision the budget really carries. For the moment, the preliminary budget reflects silence and obfuscation.

Glenn Pasanen, former associate director of City Project, teaches political science at Lehman College of the City University.

A Field of Schemes

|

|||

| • Netting the Nets by Marty Markowitz | |||

| • Cheerleaders for Real Estate? by Tom Angotti | |||

|

|

While bringing the Nets to Brooklyn may sound like an intriguing idea, it has troubling fiscal, social, and economic implications for New York City as a whole.

THE MYTH OF JOBS, RECREATION, AND HOUSING

Typically, backers of a new stadium promise it will bring jobs, jobs and more, jobs.

Supporters of this stadium project have been hypnotized by similar claims. The reality is that Yankee stadium at 57,000 seats, which is double the size of the proposed stadium in Brooklyn, only offers 65 full-time positions. Any claim that this proposed stadium would provide for significant and permanent employment is a pipe dream.

Other supporters argue that local schools and other not-for-profit organizations will use the proposed stadium for their recreational events. I respond that there are a number of proposed capital projects to renovate armories and other buildings in Brooklyn into recreational facilities. These facilities, however, do not involve the condemnation of homes and or divert public dollars for private purposes.

The developer also claims that the 17 skyscrapers in his second phase will create 4,500 to 5,500 new apartments. That claim is the biggest joke of all.

Organizations involved with affordable housing do not build high-rise apartment buildings anymore. They realize that people want housing on a human scale where children can play in a yard and neighbors can look out for each other. Furthermore, the total cost for the purchase and construction of this project will in all likelihood make housing so costly, that most working families will not be in a position to afford to live there.

DISPLACING PEOPLE, CREATING TRAFFIC

The developer also plans to use eminent domain - the power to take private property for public use - to evict entire families and businesses for his project.

Approximately 1,000 men, women and children would be displaced if the stadium plans go through (we know the number because we counted - door to door). In addition to families being removed, blocks may be closed to accommodate the stadium separating Fort Greene and Clinton Hill from the Prospect Heights community.

The junction of Flatbush and Atlantic avenues is currently congested with traffic, and adding a stadium and 17 skyscrapers would only serve to worsen traffic conditions in a dense residential community. The massive influx of automobile traffic would tie up a main artery and create the biggest parking lot in the heart of downtown Brooklyn.

Imagine 23,000 more cars - that's nearly 1,000 more an hour - and many more children with asthma.

FINANCING THE FUTURE AWAY

The biggest gamble in all of this is the method of financing the stadium.

Recently, Ratner claimed that all he wanted in exchange for this project is for New York City to kick back some of the sales and income taxes to pay off loans that he had to borrow for the project. It was reported that the total bill for the stadium and surrounding commercial, office and residential development is being estimated at $2.5 billion (not including the $300 million that he would pay for the Nets).

This project will rely upon the use of Tax Increment Financing (TIF). Tax Increment Financing is one of the fastest growing development subsidies in the country, and it diverts future property, sales and income taxes in a designated district until a developer can pay off the costs of the project. It is just another name for corporate welfare.

Bruce Ratner's past is prologue to his future. His Atlantic Center Mall, which is directly across the street from the proposed stadium, is shrouded in a cloud of controversy. It has not resulted in any appreciable benefits to the community and has a 23-year property tax abatement with a disastrous private commercial rental history.

Not only will this be bad for Brooklyn, but for all of New York.

An Independent Budget Office report on the public financing of professional stadiums concluded that dedicating taxes for huge construction projects like this ties up a significant portion of the city's revenues, and often competes with funding for other city needs like schools, police, housing, playgrounds, and sanitation.

I was elected to protect and preserve working families, to create more affordable housing and employment opportunities, and to devise economic plans that involve and respect the character of local communities. I support development of this site, but development that make sense. We need projects that will generate revenue for the area and leave the Prospect Heights community intact.

We do not need to look like an imitation of Manhattan. We stand uniquely and proudly as Brooklynites.

Letitia James represents the district 35 neighborhoods of Prospect Heights, Fort Greene, Clinton Hill and North Crown Heights in the New York City Council.

#####

In This Series:

• Field of Schemes by Letitia James

• Netting the Nets by Marty Markowitz

• Cheerleaders for Real Estate? by Tom Angotti