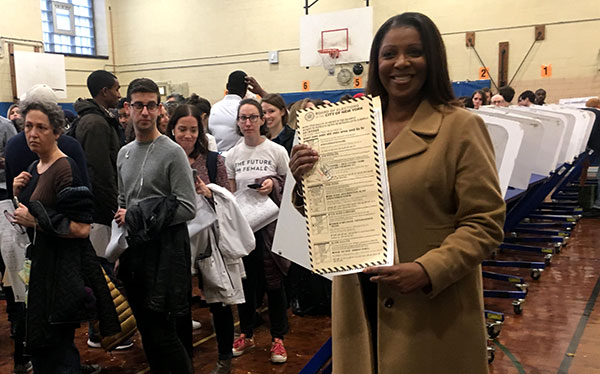

Tish James voting (photo via Gotham Gazette)

Updated as of January 29.

In February, New Yorkers will have the opportunity to cast a ballot for a new public advocate in the first-ever special election for a citywide office. The current vacancy was created when the most recent officeholder, Letitia James, was officially sworn in as the state’s attorney general, a position she won in the November general election.

The public advocate is the people’s representative, a watchdog and ombudsperson, with a post that has little direct influence over city policy but a strong bully pulpit from which proposals can be made, grievances can be amplified, and the mayor and the rest of local government can be held to account. The office is charged with hearing complaints from New Yorkers about city services and can investigate the work of city agencies though with limited ability to enforce reforms. The office holder can also introduce legislation in the City Council but cannot cast a vote.

The special election to fill one of just three popularly-elected citywide positions has a crowded field and a short timeline. Here’s what you need to know.

When is the election?

Mayor Bill de Blasio officially proclaimed on January 2 that the election would be held on Tuesday, February 26.

Who is running?

There are 23 candidates who filed petition signatures with the New York City Board of Elections to get on the ballot, but not all of them will qualify. Once the mayor signed the city proclamation, the many candidates had 12 days to collect the 3,750 petition signatures they needed to get on the ballot. Signatures can come from any registered voter in the city, and many candidates pursued far more than the minimum required in order to protect themselves from challenges of invalid signatures.

Special elections in New York are nonpartisan -- no candidate can run on an existing party line like that of the Democratic or Republican Party -- and each candidate has created their own ballot line that is not supposed to resemble another political party’s name. Another quirk in the system is that ballot position is decided by the order in which petition signatures are submitted, which made the mad scramble to get on the ballot that much more frantic.

The number of candidates, even in a narrowed field, could test the limits of modern ballot design since half a dozen sitting and former New York City Council members, several State Assembly members, and a number of activists and others outside of government are running. They include former City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito, who submitted her petition signatures first and will likely be at the top of the ballot; sitting City Council Members Jumaane Williams, Rafael Espinal, Ydanis Rodriguez, and Eric Ulrich, the lone Republican office-holder in the race; Assemblymembers Michael Blake, Latrice Walker, Ron Kim, and Daniel O’Donnell; activist and journalist Nomiki Konst; Columbia University professor David Eisenbach, who ran against James in the 2017 Democratic primary for public advocate; attorney Dawn Smalls; and entrepreneur Benjamin Yee, among others.

The actual field will become much clearer once petition challenges have been ruled on by the Board of Elections on January 29 -- eight candidates are being challenged -- whereby candidates can have their ballot access denied due to faulty petitions. Candidates often file suit to get other candidates kicked off on technicalities -- something as small as a missing cover sheet on a petition can ensure that a candidate does not qualify.

How much campaign cash can they raise and spend?

Along with his announcement of the date of the special election, the mayor also signed into law a bill sponsored by Council Member Ben Kallos that immediately puts into effect new campaign finance regulations that were approved by voters through a ballot referendum in November.

The new rules allow candidates to choose between two tiers of participation in the city’s public matching funds program, administered by the New York City Campaign Finance Board, which monitors campaign fundraising and spending. The program currently gives participating candidates a 6-to-1 match for the first $175 of every campaign contribution. Those who choose to abide by these old rules would be limited to a maximum campaign donation of $2,550, and can receive a maximum of $2.5 million in public funds.

The second, new tier allows candidates to opt for a $1,000 contribution limit and receive an 8-to-1 match in public funds for the first $250 of each contribution, allowing them to receive up to $3.4 million in public funds. To receive public funds, a candidate would have to meet the dual threshold of raising a total of $62,500 from at least 500 individual contributors.

Those that choose to participate in the public funds program will have to abide by a $4.5 million spending limit, though any candidate is unlikely to reach that astronomical number in just seven weeks. They will also have to complete a mandatory campaign finance training at the CFB.

The first campaign finance disclosure deadline passed on January 15, with several candidates showing strong fundraising numbers. The following disclosure deadline is January 25, and there are others into February.

Will the candidates debate?

Many of the candidates have already appeared and are regularly appearing at a series of public forums and debates organized by advocacy groups, political clubs, and others to lay out their platforms and positions on specific policies. But there will also be two official debates organized by the CFB. The first debate will be held February 6 and the second one is scheduled for February 20. Both will be broadcast by Spectrum News NY1, and livestreamed on NY1's website and Facebook page.

To qualify for the first debate, candidates will have to raise and spend at least $56,938 by January 21, the campaign finance disclosure deadline just prior to the debate. The second debate, for “leading contenders” will have greater thresholds -- candidates will have to raise and spend $170,813 by February 11, and must be endorsed by a state, local or federal elected official representing New York City, or by a membership organization with 250 members living in the city. The sponsors of the debates include Politico New York, Citizens Union, the League of Women Voters, the Latino Leadership Institute, Borough of Manhattan Community College, NAACP New York State Conference Metropolitan Council, and Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc., East Kings County Alumnae Chapter.

Ten candidates qualified for the first debate.

Unlike in the past, the debates will also be simulcast by the city-run NYC Life, making them freely and publicly accessible, as mandated by a law passed last year.

What will the election cost?

The New York City Board of Elections estimates that the special election will set the city back at least $15 million, a price that is nearly five times the actual annual budget of the public advocate’s office.

But, unlike a regular citywide election, there will be no costly runoff if a candidate does not meet a certain threshold. The candidate with the most votes wins, even if a large field means the winner takes a small percentage of the vote.

Who can vote and who will vote?

Every registered voter in the city can vote in the special election but turnout is likely to be low, though it is hard to predict since the city has never held a citywide special election before. New voter registration applications sent by mail must be postmarked no later than February 1 but the BOE will accept in-person applications till 5 pm on February 16.

In City Council special elections, turnout tends to be severely depressed owing to several factors -- a lack of awareness of the election, an election date outside of the expected September-November window, voter apathy.

In the 2017 election, when James was reelected to a second term, a total of 1.1 million New Yorkers voted for public advocate, only about 22 percent of the total registered voters in the city at that time.

Who will win?

Who knows. But, we do know that the winner of the special election will, if he or she wants to keep the office, have to run for reelection in the fall. By city law, there will be a typical set of primary and general elections in September and November to decide the public advocate for the rest of the current four-year term, which runs through the end of 2021. The winner of the special election will only be guaranteed the office through the end of this year.

Democratic and/or Republican primaries will be held as needed in September before a November general election. There could also be a run-off if there is a crowded primary or general election field and no candidate earns 40 percent of the vote initially. In 2013, James won the Democratic nomination in a primary run-off before easily winning the general election.

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

@samarkhurshid @GothamGazette

Note: This article has been updated to include the voter registration deadlines for the special election and other information.