Amid Talk of Recovery, Jobless Rates Reach Double Digits

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke says the recession is "very likely over at this point," although he does say that "it's still going to feel like a very weak economy for some time" because unemployment will remain high.

Grossly understating serious crises is part of the job description for the fed chairman, and Bernanke has certainly fulfilled his role here. The banking crisis may seem like it's over (for banking executives who still have their jobs, anyway), and gross domestic product may technically increase in the third quarter (in large part because of the Obama stimulus package), but the financial crisis tore through the American economy like a category 5 hurricane, and it will take more than a few more months to clear out the wreckage and for millions of people re-build to their livelihoods.

The Great Recession

Americans will be reeling from the effects of the "Great Recession" for some time. That name is apt since the current crisis is, by far, the longest and the steepest economic downturn since the 1930s. Seven million jobs lost nationally, 15 million people officially unemployed, millions losing their homes and millions losing billions in retirement savings.

In New York, a record 875,000 people are unemployed statewide, 50,000 New Yorkers lost their homes to mortgage foreclosure last year, and there have been 50,000 personal bankruptcies in the 12 months through June. Here in New York City, the official unemployment rate jumped to 10.3 percent in August, more than twice the level in the early months of 2008. It's time to take a closer look at how bad the unemployment situation really is and what it will take to get the economy back on a track to sustainable prosperity.

The Great Recession is largely the consequence of poorly regulated financial markets that went on a spree of excessive debt and risk-taking, destructive lending practices, and the use of ill-advised exotic financial instruments. It was preceded by an expansion dominated by unsustainable and dangerous bubbles in housing and the financial markets. Too many Americans borrowed more than they could afford as they tried to maintain their standard of living while their wages did not keep up with rising costs,.

In short, for the past decade, we've had a bubble-prone economy and stagnant wages for most workers where too much of our growth came from either speculation or borrowing.

It's hard to tell from the recent behavior of New York's financial giants that a year ago they were on their knees with their hands out waiting to accept the-sky-is-the-limit taxpayer bailouts. Executives of the big banks have opposed serious financial regulatory reform, rushed to resume giving themselves enormous bonus and compensation packages, and picked up where they left off in managing financial markets solely to pad their own bottom lines regardless of the impact on other businesses or the American people. As Dean Baker -- one of the few economists who was worried by the housing bubble as it inflated -- recently noted, they haven't even stopped to utter so much as a "thank you" to their benefactors.

The Real Unemployment Rate

More than in other recessions, the official unemployment rate in this downturn understates the real extent of the distress in the job market. The official unemployment rate does not reflect the steep rise in the number of discouraged workers (up 56,000 in New York over the past year) or the equally steep increase (up 186,00) in under-employment -- people who have been reduced to part-time status even though they want to work full time. With these workers factored in, the "real" unemployment rate in New York in the first half of the year was 14.1 percent, nearly three fourths again as much as the official 8.2 percent unemployment rate for the first six months.

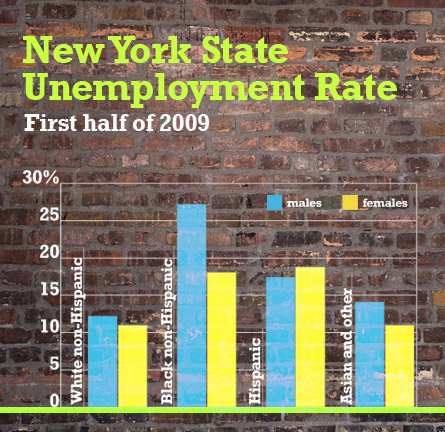

Blacks and Hispanics in New York State have been hit particularly hard. Even using the official figures, the unemployment rate for black men for the first half of 2009 was 18.3 percent, for black women 11.5 percent and for Hispanic men and women, 9.6 percent. But the real black male unemployment rate was a devastating 27 percent. Rates were somewhat lower for Hispanics and black women, but still very high. The real unemployment rate for Hispanic women was nearly 19 percent. It was 18 percent for black women and over 17 percent for Hispanic men. Real unemployment rates for white men were 12 percent, and 11 percent for white women.

All of these rates are averaged over six months to make sure that the numbers are not one-month statistical flukes, and state, not city, data was used because it provides a larger sample. Given the recent up-tick in the city's unemployment rate, it is very likely that the real unemployment rates for black and Hispanic New York City workers are now 20 percent or higher.

Meanwhile on Wall Street

Given the severity of the financial meltdown, a lot of attention has focused on job losses in finance. Certainly, there have been significant job cutbacks on Wall Street and in some other parts of the finance sector. Over the past year, employment has declined by 36,000 in the finance and insurance sector.

The greatest number of lost jobs in New Y has come from the manufacturing sector, with nearly 45,000 jobs lost over the past year. The administrative services sector has lost 32,500 jobs, retail trade 32,000, construction 23,000, professional services 22,000, wholesale trade 21,000, and information 9,000. aAll those other sectors combined have lost more than five times as many jobs as finance.

The decline in finance employment could end up being a lot less than was predicted nine or ten months ago in the immediate aftermath of the September 2008 financial market meltdown.

For many on Wall Street, bonuses running into the millions of dollars are not a thing of the past. In the city's commercial banking sector, unemployment is unchanged from a year ago, despite historically unprecedented turmoil in the market turmoil and the loss of tens of thousands of jobs elsewhere in the local economy (and millions around the country). Credit the extraordinary U.S. Treasury and Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. bailout measures, billions in taxpayer funds and limitless ultra-low interest loans courtesy of the Federal Reserve.

That's good news on the one hand; particularly in New York where spending by financial workers supports many jobs in other parts of the local economy.

Policy-makers, though, need to focus on how to restore the massive number of jobs lost throughout the economy. As often happens, innocent bystanders far from the source of the economic cataclysm are bearing the brunt of the devastation.

We need to recognize and deal with the pervasive economic insecurity of the vast majority of people. From stagnant real wages, to vanishing retirement savings, to foreclosed homes, to eroding health insurance coverage and skyrocketing health care costs, the economic challenge goes much deeper than just getting GDP growth into positive territory. The biggest challenge in putting the economy on a sustainable growth path is to recreate a wage-driven economy. What we've had is a finance bubble-driven economy.

In his recent speech on Wall Street, President Barack Obama admonished finance executives: "They (American taxpayers) shouldered the burden of the bailout, and they are still bearing the burden of the fallout -- in lost jobs and lost homes and lost opportunities. It is neither right nor responsible after you've recovered with the help of your government to shirk your obligation to the goal of wider recovery, a more stable system, and a more broadly shared prosperity."

The president went on to urge the financiers to help families modify their mortgages, more readily lend to small business owners, help communities and community development institutions, and "of course, to embrace serious financial reform"

The president's rhetoric is right on the mark.

Easing the mortgage foreclosure problem and getting banks to start lending are essential steps in moving the economy toward recovery. But, with sky-high unemployment and many debt-burdened American families reluctant to spend, another round of federal stimulus probably will be needed to help get us out of the deep hole the economy's in. And to get us on course for sustainable growth, we need policies to lift wages.

James Parrott is deputy director and chief economist of the Fiscal Policy Institute (www.fiscalpolicy.org). He has been studying and writing about the New York economy since he landed in New York City a quarter century ago.

Unemployed in New York

This story was done through a partnership between The Huffington Post's Eyes and Ears citizen journalism program and Gotham Gazette.

Joshua Deutch Dylan is a pre-bust transplant. A New Yorker for about 15 months, Dylan is already planning -- rather morosely -- his exit.

Dylan, who moved to Brooklyn from Philadelphia for a job as a legal technology consultant, was laid off six weeks ago. Now, he and his wife are struggling to get by on $430 a week -- courtesy of the New York State Department of Labor.

Their rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Bay Ridge is $2,300.

Their Volkswagen payments have been deferred just two months.

They are thinking about moving in with Dylan's parents… in New Jersey.

"We were doing pretty well for ourselves," said Dylan. Now, he adds, "Everything got sacrificed."

Dylan isn't alone. He is one of thousands of New Yorkers who lost their jobs in May, bringing the city’s unemployment rate up to 9 percent. (It was 8 percent the month before.) Now, approximately 361,000 New Yorkers are grappling with similar dilemmas, wondering how they will make rent, shell out for their Metro Card, and generally afford to stay in the country's most expensive city.

For this article, the Gotham Gazette collected stories about New Yorkers living on unemployment through the Huffington Post's Eyes and Ears citizen journalism program. (Read more about the initiative.)

Some say the State Legislature isn't helping. New York State's maximum unemployment benefit rate is $405 weekly. It's boosted temporarily to $430 thanks to the federal stimulus package, but it still pales in comparison to our neighbors. New Jersey gives $584. Massachusetts hands out $628. Pennsylvania's maximum is $558.

North Dakota pays a dollar more a week than New York does -- and you can bet the rent in Sioux County doesn't rival SoHo.

At one point this legislative session an increase seemed palatable. But now that the State Senate is sputtering and the Assembly may not return until January, most New Yorkers who are sans employment will have to find more creative ways to make ends meet.

Some already have.

A Day in the Life of the Unemployed

Janet Raiffa made more than $200,000 a year as head of recruiting for Orrick, Herrington, and Sutcliffe -- one of the largest law firms in Midtown. A mid-career professional in her 40s, Raiffa owns a two-bedroom apartment in Park Slope, which she refinanced in March, bringing her monthly payments to $3,000.

That same week, she was laid off, and her six-figure salary morphed into $430 a week -- before taxes.

Fortunate for Raiffa, she has substantial savings and can bide her time looking for future employment. So, she bird-sits for $25 an hour. She gets cash to collect signatures for politicians petitioning for this fall's election, and she writes a blog for the 405 Club -- an unemployment network whose namesake is a tribute to the state’s weekly stipends. Raiffa has even gotten paid to go to the movies and check out the upcoming trailers.

"I haven't started babysitting again, but I am actively considering it," she said with a chuckle.

Raiffa takes it well. But other New Yorkers are finding their situation harder to accept. According to the National Employment Law Project, New York's unemployment benefits only replace 27 percent of an average weekly income.

That income still has to cover the laundry, groceries and the other tabs of living in the Big Apple. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, items here can be about 90 percent more expensive than in Chicago. A can of tuna may cost $1.60 on the Upper East Side, according to the Council for Community and Economic Research, but it will cost 94 cents in the Hollywood Hills and 81 cents in Motor City. The cost of a quart of whole milk averages $2.22 nationwide. In TriBeCa it goes for $2.64, according to the council.

The city, according to some estimates, may have the highest utility costs in the country. Water rates are climbing, and the subway fare is slated to go up another 25 cents on Sunday.

The costs, for Jeremy Hoekstra, add up.

“Fast food is a special occasion,” he quips.

Nowadays even a roundtrip subway fare is a questionable expense – which is taking a serious toll on the former human resources administrator’s social life.

“The most horrible thing about it at first was I was friends with my coworkers. … Everyone at work were my best friends,” said Hoekstra, his Texas accent barely noticeable. “The feeling of loneliness sets in immediately.”

Rough Road Ahead

For now, like Raiffa, Hoekstra manages to get by. On the unemployment rolls for about six months, the 29-year-old has already sent out more than 200 resumes. He has had six interviews. Hoekstra, like thousands of others, is about to surpass his 26th week of unemployment benefits.

In better times, 26 weeks would be the cutoff. Lucky for Hoekstra, Gov. David Paterson signed another extension of benefits for 13 weeks last month, which is funded by the federal economic stimulus package. With that, some New Yorkers could receive unemployment benefits for a maximum of 72 weeks.

For some New Yorkers, those benefits are set to expire in August, said Leo Rosales of the state Department of Labor. Currently, Congress is not considering another extension, according to the office of Rep. Jerrold Nadler.

“We want to get the point across that these benefits are a safety net,” said Rosales. “It’s not a salary. It’s not an income. It’s temporary support to get them through these tough times, and there is an end date coming.”

So far, the state has borrowed about $1.3 billion from the federal government to cover those unemployment checks, which add up to $100 million weekly. It expects to borrow about $2 billion by year’s end.

But any extension doesn’t solve the real problem, say advocates. A bill introduced in the Assembly and the State Senate would have increased benefits incrementally for the next three years, going up to $475 weekly in July, and $50 every year thereafter until 2012. In future years the benefit would be set at half the average weekly wage. The bill was not taken up by the Assembly before they departed Albany last week, and its fate in the Senate seems dismal, considering the current stalemate.

For now, the unemployed have to make do with what they can: food pantries, free events, the public library (described as a “godsend” by one unemployed New Yorker). Some have even turned to food stamps -- though to get them you have to bring in less than $1,127 a month, which will exclude anyone who takes home the maximum weekly benefit.

Others just rely on generosity of others.

Speaking from his Midtown home this week, Tom Adcock, a New York Law Journal reporter turned unemployed novelist, lamented that his 62 years have made him virtually unemployable. But, he adds, he’ll get by.

"I can't afford to join friends in restaurants," Adcock said. “Tonight I’m entertaining at home. Hopefully, my friends will not come empty handed.”