How to Balance the State Budget

The financial meltdown and the recession have thrown state budgets out of whack across the country. Plummeting revenues have given New York State a projected budget gap of $1.7 billion for the current fiscal year and $13.7 billion for the new fiscal year that will begin April 1. The combined deficits of New York and 45 other states through 2010 are predicted to reach a staggering $350 billion, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Meanwhile the recession is taking a toll on people across the state. Tens of thousands of New Yorkers have lost their jobs, their homes or their hopes for a secure retirement or a better future for their children. New York's unemployment rate jumped by a full percentage point in December to 7 percent, the greatest one-month increase on record since 1976. The state has lost 121,000 jobs since its August 2008 job peak. More than 50,000 New Yorkers lost their homes through mortgage foreclosures last year.

As the economic damage ripples out from Wall Street, Gov. David Paterson has proposed drastically slashing state spending. School aid, health care, SUNY and CUNY, child care, program for the elderly, homeless prevention and long-overdue wage increases for social service workers struggling to stay above the poverty line will all feel the effects of the budget ax. While he chops away, though, the governor has steadfastly refused to call for a progressive hike in the state income tax -- an increase that would affect only the most affluent New Yorkers.

For the governor, "shared sacrifice" means that the state's low- and moderate-income families and communities must sacrifice while the fortunate few at the top, who benefited the most from the tax cuts of the last 15 years and from this decade's economic growth, will emerge from the budget largely unscathed.

Too Much Spending -- or Too Little Revenue?

Anti-government voices have mounted a steady drumbeat calling for steep budget cuts, ostensibly to rein in "out of control" state spending. The reality? State spending has increased to fund important new commitments such as providing medical care to people without health insurance and aiding urban school districts with high concentrations of children from poor families. The state government also dramatically expanded spending on property tax relief and acted to partially undo years of underinvestment in mass transit and public higher education.

Aside from these major commitments—all supported, by the way, by David Paterson when he was a state senator and lieutenant governor--state spending from 2004 to 2008 grew at less than 2.9 percent a year, barely the pace of consumer inflation.

What the state failed to do, however, was provide the revenues needed to finance such initiatives through the ebbs and flows of the business cycle. Much of the state's current budget crisis might have been averted had the state reversed even part of the tax-cutting spree carried out from 1994 through 2000. All tolled, these cuts now reduce the state's tax revenues by about $20 billion a year, an amount that would erase even the huge projected budget gaps of $17 billion for 2011 and 2012.

Less Pain, More Gain

Like the other 49 states, New York has to balance its budget in both good times and bad. Facing a sizable budget gap during a recession, states have only bad choices. Neither cutting spending nor raising taxes eases the downturn.

Many economists, however, point out that it is less harmful to the economy to raise taxes in a way that limits its effects largely to high income people than to cut state spending that mainly benefits low- and moderate-income people or that pays the salaries of teachers, police officers and other civil servants. In December, 120 economists from across the state sent a letter to Paterson saying, "Economic theory and historical experience [show] it is economically preferable to raise taxes on those with high incomes than to cut state expenditures."

This is because high earners typically spend only a fraction of their incomes in any given year, saving the rest. On the other hand, state spending goes to pay workers, provide services and put money in the hands of New Yorkers in need. This means the money goes directly into the economy, priming the pump at a time when it is desperately needed. Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz of Columbia University made the same point in a letter to the governor last March.

Public opinion across the state strongly favors increasing income taxes on high earners over cutting spending for health care and education. The governor, though, has argued that raising taxes on the wealthy will drive them from the state.

No evidence exists to support that claim. In 2003, New York temporarily raised its top income tax rate from 6.85 percent to 7.7 percent. During the three years that this increase was in effect, the number of high-income returns grew significantly. This experience in New Jersey, which permanently raised its top personal income tax rate to 8.97 percent in 2004, has been similar, according to a Princeton University study.

Beyond a High-End Tax Hike

Paterson and the two top legislative leaders -- Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and Senate Majority Leader Malcolm Smith -- have committed to closing the projected $1.7 billion budget gap for the current fiscal year by Feb. 4, even though the year does not end until March 31.

What should they do? In addition to its investments in infrastructure, unemployment insurance modernization and other measures, the massive economic recovery bill now making its way through Congress includes aid, called “state fiscal relief,” for the explicit purpose of helping states balance their budgets without putting too much additional drag on the economy. Since this legislation is likely to go to President Barack Obama for his signature in mid to late February, the sensible course would be for Paterson and the legislature to wait to see exactly how much “budget balancing” aid New York will receive under the final legislation. The chances are excellent to certain that the state will get several billion dollars it can use right away, since important parts of the “state fiscal relief” is retroactive to Oct. 31, 2008.

In the unlikely event that the immediate “state fiscal relief” does not close this year's gap, the governor has already identified at least $600 million in various reserve funds that could be tapped to balance the books. On top of that, the state has at least $1 billion in its Tax Stabilization Reserve Fund that it could us if needed. Even if it had to borrow against that -- which seems unlikely -- the state still has $400 million in a newer "rainy day" fund as well as a few hundred million in other reserves.

Closing the projected $13.7 billion gap for the 2010 fiscal year will prove more difficult. A progressive tax increase would generate roughly $5 billion. This, along with several billion more from an increase in the federal payments for Medicaid or state fiscal relief in the stimulus package will address most of the budget gap.

Some budget cuts may be unavoidable, but the state should also consider closing tax loopholes such as one that benefits non-resident hedge fund general partners working in New York State and taking other actions to generate budget savings. These could include ending the wasteful and failed Empire Zones program, increasing the use of state engineers rather than contracting out that work to expensive consultants, or using the state's sizable purchasing power to get better prices on prescription drugs.

Restoring Tax Fairness

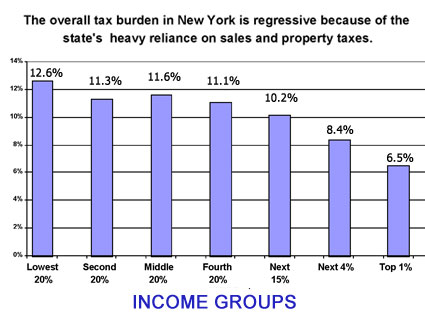

Raising taxes on high earners would also be a step toward restoring fairness to New York's graduated income tax, which has become significantly less graduated over the years. Today, because of the state's increased reliance on regressive sales and property taxes, New York's middle- and lower-income households pay a higher share of their incomes in state and local taxes than the top 1 percent or the top 5 percent (see chart).

Moreover, as astounding as it may seem, data indicate that all of the income growth in New York State from 2002 to 2009 has gone to the wealthiest 5 percent. In 2009, the other 95 percent of households have roughly the same incomes they had in 2002. When you factor in inflation, the combined income of the bottom 95 percent of New Yorkers actually shrunk.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman recently wrote in his New York Times column that, in the absence of Obama's massive stimulus proposal, we might see 50 Herbert Hoovers in state houses across the country respond to revenue shortfalls by slashing their budgets or raising regressive taxes, making the economy worse in the process. The new stimulus program is designed, in part, to head off that result. For the part of the budget gap that cannot be closed through federal funds, the state should turn to progressive tax policies. This is the right economic policy, sound fiscal policy, and the only approach in keeping with the governor's theme of "shared sacrifice".

Frank Mauro is the executive director of the Fiscal Policy Institute. James Parrott writes a regular column on the economy for the Gotham Gazette and is FPI’s deputy director and chief economist.

An Election Year Budget

It was the same scene: reporters scrunched into rows of blue plastic folding chairs chaotically checking their BlackBerrys; the chiefs of the city government's largest departments lining the front row; and the mayor -- charcoal power suit, red tie -- delivering a particularly morose PowerPoint, presenting a practically apocalyptic view of the city's budget.

Let the 2010 budget season begin.

On Friday, Mayor Michael Bloomberg released his preliminary budget for fiscal year 2010, which starts July 1. With the economic meltdown showing no sign of stopping, the mayor proposed to slash almost $1 billion from city spending and raise the city's sales tax to create $900 million in revenue. He has threatened to chop the city's work force by about 8 percent -- including 14,000 teachers -- if funding from Albany does not materialize or municipal employee unions do not compromise on health benefits.

Though most city officials say the country's dire straits call for serious measures, they also recognize that 2009 is an election year. Election years breed political compromises. Not only will city officials hear from advocates and constituents protesting the cuts, they also will hear from their political opponents. Inevitably, decisions made in June affect the election's outcome in November.

Forget the 2010 budget cycle. Say hello to the '09 campaign season.

The Budget Breakdown

In 2005, after several years of gloomy budget scenarios, the mayor was upbeat -- he called his preliminary budget then "cautiously optimistic."

Translation: Things had improved since the downturn following September 11th, and Bloomberg was looking for another four years as the fiscal guardian of one of the biggest budgets in the country.

Fast forward four years and we see the same mayor seeking another term in office (albeit unexpectedly). This time around, with the economy in disarray, Bloomberg's forecast is less confident.

"I am as optimistic as I can possibly be for the longer term," the mayor said, reiterating that the city would not return to the 1970s when core services were slashed due to an economic downturn.

"I think we'll be able to do it together," the mayor added. "We have the seasoned leadership and the public support."

The city faces a yawning $4 billion budget gap due to a decline in tax revenues, attributed to the financial crisis on Wall Street. To address these fiscal woes, the mayor proposed a $58.8 billion budget -- a decrease from the projected 2009 budget of $60.1 billion. The city's deficit, the mayor reminded reporters Friday, could have been as much as $6 billion if the City Council and mayor had not acted to cut spending and increase property taxes late last year.

Essential to the mayor's proposal is funding from both the federal and state governments -- funding that is far from guaranteed. Lobbing the problem a few hours north, the mayor urged the State Legislature to rescind a proposed $770 million cut to education aid for the city or see close to 14,000 layoffs at the Department of Education, most likely teachers (with attrition that number is 15,630). The mayor said aid the state receives from Washington's economic stimulus package could right Albany's wrong. (See related story on state budget cuts.)

"I am sympathetic with the state," the mayor said, referring to the projected $15.4 billion deficit in Albany. "Here is a chance for Albany to pay for their fair share of education with someone else's money. If there was ever a case for us to put pressure on them, it's now."

The mayor plans on filling the budget gap through $1 billion in aid from the federal government for Medicaid, almost $1 billion in agency spending cuts and about $1 billion from the restoration of state cuts and renegotiating health care benefits for union workers. He also is considering increasing the sales tax to 8.625 percent from 8.375 percent in addition to repealing the exemption for clothing and starting to tax items, like haircuts that previously were tax-free.

Bloomberg said a sales tax increase is not definite since the economic climate is still settling and revenues could change between now and when the budget must be approved in June.

Overall, unless the city gets help from unions and the state, the municipal workforce could decline by nearly 23,000, Bloomberg said, through both layoffs and attrition.

Under the mayor's doomsday proposal, the majority of layoffs are slated for education, but other departments would not be immune: the Administration for Children's Services could see 608 layoffs, Homeless Services 222, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene 57 and the Finance Department 17. The mayor proposed losing 7,686 positions through attrition from multiple agencies, including a reduction of 1,000 uniformed police officers.

The Teachers Take Their Toll

Just in time for the Superbowl, the mayor punted.

The most drastic of cuts, specifically the Department of Education layoffs, which comprise 80 percent of the total proposed workforce reduction, are because of Albany, the mayor said.

That sparked this reaction from United Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten: "The union has pledged, and indeed has been working together with the mayor on the federal recovery and on ensuring we get a fair share from Albany. But making virtually all our first, second and third-year teachers pawns in this political battle is callous and unfair to them and their students. Worse, in blaming Albany, the city itself masks the magnitude of its own cuts.”

Weingarten is not alone in thinking the mayor is pegging Albany for the city's problems.

Baruch College Professor Doug Muzzio said the mayor's budget was overflowing with "wishing and hoping." If the federal and state funds he is expecting do not come through, then his re-election prospects could suffer.

"If you lay off 15,000 teachers, man, that’s going to resonate," Muzzio said. "It's going to resonate loudly, through bull horns."

Whether it's political maneuvering or financial strategy, other officials and political observers think the mayor has a point. At the end of the day, they say, teachers will not be sacrificed.

"It would not be acceptable to lose 15,000 teachers, period," said Councilmember David Yassky, who also is a candidate for city comptroller. "The mayor is absolutely right that it's up to Albany to keep our school funding constant. What he is trying to highlight there is that the governor's budget would reduce our school aid quite dramatically."

Already Unpopular Cuts

As for spending in general, Bloomberg recognized some departments were harder hit in this preliminary budget than others.

"It would be fair to say everybody takes the same hit, but the real world is you have to keep the streets safe, and the real world is you have to have a certain amount of guards for each prisoner," Bloomberg warned.

Of all the agency cuts, social services have been slashed the most -- by about 8.2 percent. Youth programs, libraries, cultural affairs, CUNY, transportation, and health and mental hygiene all have cuts around 7 percent. The Administration for Children's Services, which is slated for significant layoffs in comparison to some agencies, has seen a 6 percent cut.

The police, fire, correction and sanitation departments all received cuts of between 2 and 3 percent.

But how will these reductions, if approved by the City Council come June, affect the average New Yorker?

The Sanitation Department will reevaluate trash routes (and their frequency) so workers will pick up more tonnage. The city is doing away with pickups of grass clippings. After-school programs, including summer youth programs, will be cut significantly.

Bloomberg proposed to eliminate dual company firehouses by taking away either an engine or a ladder in certain stations. He also proposed to eliminate a firefighter position on 64 engines, bringing down the count to four (It will be done through attrition and it excludes lieutenants on the scene).

He wants to increase rates for single rate parking meters from 50 cents to 75 cents an hour, stop the city's nutrition counseling for those with HIV, increase admission fees at the Central Park Zoo and the Queens and Prospect Park wildlife centers and cut funding to senior centers.

Proposals floated to increase revenue include an increase in CUNY tuition by $200 a semester and a 5-cent tax on plastic bags, both of which would require approval by the state government.

All of these proposals, particularly the cuts to social services, could provide ammunition for challengers come November.

"I think it's shortsighted by Mayor Bloomberg to propose these cuts in terms of managing the city's budget and in terms of managing his political future," said Sean Barry, the director of the NYC Aids Housing Network. "We don’t want to return to the time where New York City is warehousing homeless people with AIDS in welfare hotels."

Politics or Policy

Bloomberg didn't have the last word on Friday.

Not to be outdone, one of the mayor's political rivals, Comptroller William Thompson, came out with his own proposal immediately following the address: upping the city's personal income tax on those earning more than $500,000.

When Gotham Gazette asked for more details about the comptroller's suggestion, a spokesman said Thompson was reviewing a number of ideas and would release details once finished.

Already some advocates and council members see an income tax increase as a better option than a hike in the sales tax, which they call "regressive," since it will have a disproportionate effect on lower-income people.

"Sales tax are regressive," said Jennifer March-Joly, executive director of Citizens' Committee for Children of New York. "You raise revenue that way, that’s clear, but the problem is for those that need to shop and make far less money. It's much more burdensome than the income tax."

With sides taken and criticism thrown, revenue options may be the first concrete mayoral campaign issue in 2009.

"The mayor’s plan would balance the budget on the backs of working people," read a statement from Thompson released following the mayor's budget address. "The mayor’s budget proposal relies far too heavily on a sales tax increase at a time when the city’s hardworking families and small businesses are suffering."

The mayor said he had not put an income tax increase on the table, because he anticipated the state would increase it to solve its own fiscal woes. (See related story.)

Tackling A Base

A critical element in the mayor's budget plan is tapping city unions to pay 10 percent of their health insurance premiums. According to the Independent Budget Office, 90 percent of city employees enrolled in its insurance program do not premiums.

Brave, maybe. But political observers say it could be tough to cross unions in an election year.

"The mayor is now in a position, regardless of re-election issues he is going to have, to make the unions his partners or his election will be more problematic," said a source close to the unions in New York City. "If he gets re-elected he will have real war."

Obviously, Bloomberg does not rely on the city's unions for financial support for his campaigns, as many politicians without billions of dollars do. In a citywide election, though, union support is key.

So far, the reaction to his proposal has been icy.

In response, Lillian Roberts, the executive director of city's largest municipal employees union, District Council 37, released the following statement: "Union members should not be asked to shoulder the bulk of this burden. Workers did not create this fiscal crisis and cutting into their hard earned benefits should not be viewed as the quick fix that will solve it."

Others scoffed at how realistic this proposal would be: "Be serious here, Mr. Mayor," quipped Muzzio.

The mayor has previously been criticized for not doing more to rein in rising pension and benefit costs, often thought of as "uncontrollable." Some, including political consultant Joseph Mercurio, say now is as good a time as any to negotiate union contracts. According to the mayor's office, payments to retirees for pensions and health benefits will increase from $11.7 billion in 2007 to $16.8 billion in 2015.

An analysis last year by the Independent Budget Office projected about $400 million in savings could be garnered during the first year of city employees paying 10 percent of their premiums.

The Political Hurdles

Councilmember John Liu, a candidate for public advocate, recognizes a tough budget year can mean tough politics.

"It stinks to run for election in a very difficult time," said Liu.

Though officials interviewed by Gotham Gazette say politics will not enter into their decisions on the budget, their policy choices could certainly affect the election.

"Politics plays a role in everything," said Councilmember Letitia James, who is running for re-election to her seat in Brooklyn.

Bloomberg extended term limits and launched his third term candidacy because he said he was needed to lead the city through tough times. That said, the outcome of this year's budget could dramatically influence whom the electorate (which still favors Bloomberg) chooses this November.

Most politicians, even those who themselves are seeking higher office (like Yassky, Liu or David Weprin), contend politics will not come into play this budget cycle.

"It's fiscal reality," said Councilmember David Weprin, the council's finance committee chair and a candidate for comptroller. "I think you need somebody in the comptroller's office that is going to recognize the fiscal situation and deal with it."

Yassky, agreed. "You first decide what's the right policy and then you go and make your case to voters and they can understand it."

Arguably the most eternal optimist is the alleged non-politician, the mayor himself.

"I hope and I expect that the fact that it's an election year will not enter into it at all, because (the council doesn't) have any choice, nor do I," the mayor said Friday. "We have to address these issues, and I would argue the public wants these issues addressed and wants you to make the tough decisions. My advice to anyone in government is do what you think is right and in the long term it will work out."

Can Obama Help Save New York?

As Barack Obama takes office today, many New Yorkers have high hopes that change has come -- and it will be change for the better. Much of that hope springs from excitement surrounding the first African American president ever and the first one in decades with urban connections. And in this overwhelmingly Democratic city, where Obama beat Republican John McCain by a four-to-one margin, there is a palpable hunger for new ideas and attitudes.

Like most Americans, New Yorkers want action too -- particularly on the economy. The recession has hit New York, the home of Wall Street, hard, with rising unemployment, job losses and slowdowns in all types of businesses. As a result, the state faces a $15 billion deficit over the next 15 months and the latest projections show the city government, thought to be on firmer ground, peering into a $4.3 billion abyss.

City and state leaders, along with fiscal experts and ordinary New Yorkers, hope Obama can help. At his State of the City last week, Mayor Michael Bloomberg rolled off a number of initiatives that called for some federal dollars, including a proposal to revamp the city's air traffic control system and a pilot program that offers jobs to struggling students if they stay in school. (For more on the mayor's State of the City, see A Recovery Package From Bloomberg.)

Highest on the city's wish list may be federal dollars for infrastructure. "Our cities have to be a central focus of any recovery plan," Bloomberg said recently. Any federal funding should first go to our urban environments, Bloomberg added, especially for bridges, roads, trains and tunnels.

Other New Yorkers have their own ideas. Here several experts offer their views about the proposed economic stimulus package and what the new administration can do to help lift New York -- and the nation -- out of the economic crisis.

Paying Attention to Cities By Jonathan Bowles

After years of federal policies neglecting urban areas, Barack Obama has sent some encouraging signals that he understands their importance. Certainly, New York could use a helping hand. The director of the Center for the Urban Future lays out some ideas for what the president could do to aid New York.

An $825 Billion First Step By James Parrott

The stimulus package proposed by Congress is key to halting the economy's downward spiral but it will not solve all our problems. Economist James Parrott of the Fiscal Policy Institute looks at what the package would do -- and what more needs to be done.

Using the Crisis to Prevent the Next One By J. Mijin Cha

The current turmoil can help us reduce our dependence on Wall Street and create good "green collar" jobs that help fuel a resurgence of the middle class. The director of campaign research at the Urban Agenda explains how.

Infrastructure Investments that Make Sense By Carter Craft

As big as the stimulus package may be, the country has to invest the money wisely. An urban planner offers some novel ideas for New York projects -- from recycling grease to ferries for freight.

From Gas-Guzzling Cars to Clean Buses By Charles Stone

Simply lending funds to struggling auto companies won't spur economic growth. Instead, an economist suggests, the government should create a voucher program to deploy the resources of the auto companies, spur investment -- and help the environment.

Previous Articles

A Federal Stimulus for City Parks By Anne Schwartz

Advocates hope that President Obama and Congress will recognize that funding parks would not only improve the quality of life and the environment but also spur investment and raise real estate values.

Stimulus Money: The Downturn's Silver Lining? By Graham Beck

The stimulus package could offer more federal funds for transportation projects. The MTA is making its list, but there are sure to be lots of restrictions -- and competition