Stated Meeting: Tax Bills on the Floor

The City Council has its own solution to New York's fiscal crisis: Don't tax New Yorkers. Tax tourists.

At least that is what Councilmember Lewis Fidler said Tuesday when he introduced a bill to increase the city's hotel tax by less than 1 percent. The bill has the support of Council Speaker Christine Quinn.

A less acceptable proposal, according to some council members, also was put before the council. It seeks to increase the city's property tax rate by 7 percent. Mayor Michael Bloomberg introduced the property tax legislation and argues the city must raise taxes and cut spending to close a yawning budget hole in fiscal year 2010 and a smaller one in this year's budget.

The mayor has not taken a positionon the hotel bill, though he has opposed similar proposals in the past.

These bills are the first tangible signs of the fiscal crisis in the council chamber, and they follow an unusual bout of mid-year public hearings on agency spending cuts.

Taxing Hotels and Houses

Fidler's bill (Intro 879) would increase the city's hotel tax from 5 percent to 5.875 percent, adding another $2.62 on an average $300 a room rate. The increase could raise an estimated $80 million in new revenue, say city officials.

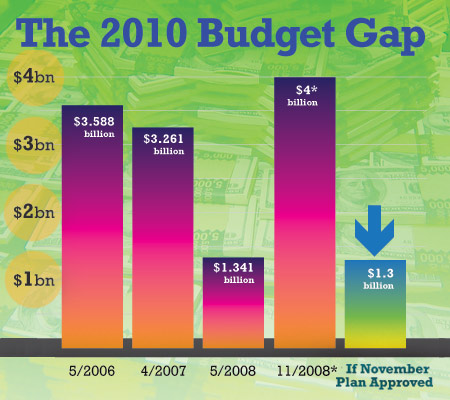

For the current budget year, which ends in July, the city is facing an approximately $300 million budget gap. That hole widens to about $4 billion for next year's budget if the city does not cut spending or raise taxes this year, according to the mayor's November budget proposal.

The hike in the hotel tax, say supporters, could help close that gap, without deterring tourists from visiting the Big Apple.

"If you were to spend a week in the city of New York and spend $2,100 on your hotel, are you really going to change those plans because someone just told you that it went to $2,120?" asked Fidler. "I don't think so. I don't think $20 is going to stop anyone from coming to the greatest city in the world."

Not everyone is so sure. The Hotel Association of New York City vigorously opposes the bill, arguing the increase would drive away business and result in a loss of $533 million in room costs and tourist spending.

"Any tax increase would be gravely detrimental to the city's economic health," said Joseph E. Spinnato, the president of the association, in a prepared statement. "This increase could bring us back to the dark days of the 1990s when convention planners -- outraged by the fact that city policymakers would take advantage of our visitors to fix a budget hole -- boycotted our area."

The association argues that the city's tax is already 14.54 percent, factoring in the $2 per night hotel occupancy tax and the $1.50 Javits Center surcharge.

Fidler says, however, the "insignificant" increase does not compare to the skyrocketing hotel taxes during the 1990s.

"In this difficult economic climate, the truth is, as unfortunate as it is, everyone is going to have to pitch in," said Quinn. "This includes the visitors to our city."

A City Council spokesperson said the city would not have to receive approval from Albany to raise the hotel tax. Nor would it have to seek Albany's approval if the council chose to pass the mayor's legislation (Intro 887) and increase property taxes. The current legislation does not specifically state a 7 percent increase, though that is what the mayor has proposed in his November budget proposal.

Quinn said she has not taken a position on the property tax bill yet. She added the council has the power to amend the property tax bill and so could revise the 7 percent figure.

If approved, a 7 percent increase would raise about $576 million in additional revenue.

Women and Minority Businesses Boosted

In addition to introducing the tax legislation, the council unanimously approved legislation (Intro 888) encouraging companies that receive industrial or commercial tax abatements to contract with businesses owned by minorities or women.

The bill requires a business that receives a tax break for a project worth more than $1.5 million to solicit bids from at least three women or minority owned businesses for each subcontracting opportunity. The businesses would also have to identify firms in the city's minority and women businesses directory who could do the work.

If a firm does not comply with the bill, it could lose its tax break.

Budget Battle: Round 1

Â

fiscal year 2009 gap that has grown since the budget was passed in June.

See how the city has projected the budget deficit for FY 2010 over the years. Even in 2006, when the cityÂąs finances were in the black, the Bloomberg administration predicted a hole.

Get rid of a property tax rebate or more than three police classes of 1,000 officers -- each will save about the same amount.

Increase property taxes by more than $200 for an average one- to three- family home or, maybe, slash supplies for public schools classrooms. Shut down the city's century-old dental program or add a five-cent tax on plastic bags.

Times are tough, say city officials, and we have to set some priorities.

This city budget season has started two months early, and the debate already involves lawsuits and squabbling. While it's not unprecedented, Mayor Michael Bloomberg's move to seriously revise city spending mid-way through the fiscal year gives some indication of how our economy has spoiled. Like it or not, some programs will have to be chopped.

Since the mayor announced his intention more than two weeks ago to cut city spending, rescind the $400 property tax rebate (a proposal whose fate remains uncertain) and increase property taxes by 7 percent come January, the City Council, uncharacteristically, has not waved any white flags. In some cases, they have called war.

Today is the last day of a weeks worth of hearings. Lines have been drawn and a victor is far from chosen. A vote is expected in early December.

Planning Early

In his typical fashion, Bloomberg's plan does not focus primarily on this year's gap, but the budget hole the city will face in 2010 and beyond.

He plans on cutting this year's budget -- through both raising taxes and reducing spending -- by $2.2 billion. (For more on the mayor's budget strategy, go here.)

That budget hole: $300 million.

Most of these cuts will go toward reducing the budget gap the city faces in fiscal year 2010. If the mayor's proposals win approval, they could reduce that deficit to an estimated $1.3 billion.

Why take these measures now?

"Everyone has to understand this is the only way we're going to get through this and have a future," Bloomberg said, sounding particularly doomsdayish, at a financial presentation earlier this month at City Hall.

The presentation, which normally takes place in January, sprang from the turmoil on Wall Street, which, Bloomberg argues, means the city needs to start cutting costs immediately -- seven months before the end of the fiscal year.

Most fiscal watchdogs say taking action early -- and addressing our fiscal problems before they turn too dire -- is characteristic of Bloomberg's approach to budget balancing.

"It's certainly consistent with the way he's operated since taking office," said Doug Turetsky of the Independent Budget Office. "He doesn't just wait until you get there to start doing things."

Even so, there still may be some wiggle room now. For the City Council, that comes in a $400 property tax rebate.

Tax and Spend Policy

Rarely do the City Council Speaker Christine Quinn and Mayor Bloomberg disagree publicly. Quinn has shepherded two controversial pieces of legislation -- both spearheaded by Bloomberg – through the council this year alone: term limits and congestion pricing.

But when it comes to delivering $400 checks to thousands of city homeowners, Quinn has staked out a position on one side, Bloomberg on the other.

Though the speaker declined to promise residents that they would get their rebate checks, which were supposed to be mailed in early October, Quinn said the council would do anything in its power to preserve the rebate.

"I can guarantee New Yorkers we are going to fight as hard as we can to get them those checks as quickly as possible," Quinn said at a press conference last week.

Part of that fight comes in the form of a lawsuit filed by council members Vincent Ignizio, James Oddo, Vincent Gentile, Lewis Fidler and Tony Avella. Assemblymember Louis Tobacco also signed onto the suit.

"This is just one of those out of touch with reality moments that you guys have over there from time to time," said Fidler addressing administration officials at a budget hearing on the rebate check. "I don't think you realize how much people who are living hand to mouth are expecting that check."

The council has argued the mayor cannot withhold the rebate checks without its approval -- which is a nonstarter. Bloomberg, who initially said he would not issue the check because the city had "no money," has started to back down. Last week, the mayor said he would work with the council to find "balance."

The rebate would cost the city $256 million. The tax hole for this year is $300 million. Do the math: The mayor's plan to increase taxes by 7 percent in January would bring $576 million -- more than enough to cover this year's gap. In fact, under his plan, the city would end the year with a surplus.

Again, it's about priorities.

Though the $400 rebate has become the council's cause of the moment, others say it's a regressive tax and the city should do away with it.

"They shouldn't have had the rebate in the first place," said Carol Kellerman, executive director of the Citizens Budget Commission. "This is not a need based amount. This is an amount if you are a single-family property owner. It doesn't matter if it's a townhouse on Fifth Avenue."

Who Wins and Who Loses

In addition to the tax increases, Bloomberg has proposed about $500 million in spending cuts in this fiscal year and more than $1 billion for next year's fiscal year. The agency cuts equal a reduction of 2.2 percent for fiscal year 2009 citywide.

Agencies have been ordered to cut their budgets by 2.5 percent for this year's budget and by 5 percent for fiscal year 2010. Some departments have received marginally more -- or less -- funding than others, but for the most part the cuts are across the board. (Check out a full funding breakdown here)

But for small agencies, a 2.5 percent cut can mean a lot. In addition, these cuts come on top of the spending reductions, which mostly hit social services agencies, that the council approved in June.

"They are looking to cut out anything that they are not required to provide," said Allison Sesso, deputy executive director of the Human Services Council. "This is just compounding cuts that were already taking place."

For example, the city plans to reduce the Department for the Aging's budget for "non-core social services," which has raised an alarm among some advocates. It also proposes to eliminate a $1.2 million program that provides adult day care to debilitated seniors and is doubling the co-payments parents pay to the Administration for Children's Services for day care programs from $1 to $2.

The mayor has also proposed eliminating 127 positions at the children's services agency, increasing caseloads for supervisors*. The city plans to close a job center and a clinic treating sexually transmitted diseases in Harlem and a homeless shelter at Bellevue Hospital Center.

At the Department of Homeless Services, the city will save $5 million in 2010 by providing incentives to city contractors for getting families out of emergency shelters and into public housing. Advocates say, however, the amount of available housing for these families remains stagnant.

The department also plans to require homeless working families to contribute to the cost of their shelter, which could bring in about $1.3 million next year.

For some advocates, that move touches a nerve.

"Many families actually save money while they're in a shelter," said Patrick Markee, a senior policy analyst at the Coalition for the Homeless. "It seems counterproductive and a little bit cold hearted."

Reductions in Blue

The Police Department plans to do its part to close the budget gap by putting fewer cops on the street. According to Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly, the department will cut new hires by half, eliminating one of the two yearly officer-training classes. Normally, police academy classes begin in January and July, and slightly more than a thousand officers graduate from each class. The elimination of the January class will save $36 million next year, but it will bring the department’s force to its lowest level in years. Along with reducing the number of new recruits, Kelly said, further reductions will come through attrition and a cut in civilian staffing, generally in clerical, administrative and custodial positions.

Before Bloomberg mandated the budget cuts, the department had planned on a peak headcount next year of almost 37,000 uniformed officers. At a joint hearing of the City Council’s public safety and finance committees on Nov. 24, council members expressed concern that crime would rise with fewer officers on the street. Kelly countered that the overall crime rate has decreased by 28 percent since 2001, when there were about 40,000 officers on the force—the department’s all-time peak.

"We’re going to do everything we possibly can to continue to reduce crime in this city," Kelly told committee members. "We’ve done it effectively at a time when we lost some 5,000 officers. Crime has still come down and it's safer than its ever been."

Public safety committee chair Peter Vallone Jr. was not convinced. While overall crime has fallen, Vallone said, certain violent crimes have increased: Murder is up 6 percent, and rape and burglary are each up 2 percent so far this year. And, he said, the decline this year in overall crime is the smallest so far since 2001.

"The NYPD always says it can do more with less, but at this point, Batman would have trouble doing more with the amount of resources we have allotted," Vallone said in a statement issued after the hearing. "If public safety suffers, everything suffers."

Vallone is particularly worried that any rise in crime could exacerbate New York’s economic crisis, affecting tourism, retail and real estate.

The department plans additional savings by shifting additional law enforcement duties to traffic enforcement agents. For example, until now, only uniformed police officers could ticket vehicles for obstructing traffic at intersections. Gov. David Paterson recently signed a bill requested by Mayor Michael Bloomberg that allows the city’s traffic enforcement agents to issue these tickets.

Classroom Cuts

Even city's public school have not escaped the current round of budget cuts. The administration has proposed $180 million in cuts to the Department of Education's $21 billion budget this year and $385 million next year. In June, the department took a $200 million reduction but, partly through the efforts of the council, school classrooms were spared.

This time around though, classrooms would see a $103 million reduction. Where exactly that would fall will remain largely up to individual principals, although no teachers will lose their jobs. "The principals have made it clear that none of these cuts are easy or without pain, but they expected these cuts," Deputy Chancellor Kathleen Grimm told City Council.

For the first time, the administration proposes to reduce spending at the District 75 schools serving handicapped students – although by a relatively modest one half of one percent.

Other cuts will come in administration where the department proposes to eliminate 338 positions, cut back on the Teaching Fellows program, trim expenses on meetings and eliminate science assessment. Some maintenance positions serving schools will also be lost.

Given how volatile school spending cuts tend to be, Friday's hearing on the reductions was relatively low key. Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum reiterated her concerns about the department's spending on its so-called accountability initiative, Fidler suggested the school use energy efficient light bulbs, and John Liu wondered how much the department had spent on an ill-fated plan to centralize kindergarten admission.

There were, though, apparently no real fireworks. Those could come at public hearings today. On the other hand, almost everyone at the hearing realized this round of cuts could be the relative calm before the storm. The state has not enacted any cuts for now, but everyone anticipates that will change. With the state providing 41 percent of the Department of Education's funds, how much of the cuts could fall on city schools remains anyone's guess.

"I make it a policy not to predict what Albany will do," Grimm said.

Other Battlegrounds

At another of many budget hearings last week, Councilmember Gale Brewer questioned the administration on how it collects taxes from vacant buildings.

Sitting at the very top of the dais, Brewer couldn't help but add a closing remark.

"Don't cut the libraries," she jabbed.

A typical council-mayoral battleground, libraries under the budget plan would cut back hours to an average of five and a half days from the current six. Some branches, said an aide to the council's libraries subcommittee chair, Gentile, would only be open for five days, while others will be budgeted for the extra half day. The library cut would save $8 million in this fiscal year.

The council will also almost certainly object to cuts at the police department and the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. The administration has proposed delaying a police class of 1,000 officers, reducing the overall headcount at the department. The training program at the fire department's academy will be cut from 23 weeks to 18 and several engine companies will lose their night hours, for a combined savings of $7.5 million.

Councilmember Peter Vallone, head of the council's public safety committee, has made this police headcount reduction part of his checklist for elimination.

The mayor's proposal to eliminate the city's dental program for children, which began in 1903, is also drilling up some ire. The program serves 1 percent of the city's kids and costs $2.5 million.

Looking Forward

Most agree the worst is to come.

All of these cuts do not factor in an estimated $12.5 billion deficit in Albany, which is sure to translate into deeper slices in school aid statewide. This year, the city received $11.7 billion from the state -- about 20 percent of the entire budget.

The State Senate is set to hold a special session next month to consider cuts by Gov. David Paterson. The governor is also scheduled to release an updated fiscal response to the crisis in December.

These budget revisions also do not take into account debilitating deficits at the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and the New York City Housing Authority. The city's public hospitals network, the Health and Hospitals Corp., is also struggling, say officials.

Our fiscal troubles are far from over.

"I think this is a very difficult budget year, but you typically don't see these budget modifications change very much," said Markee. "We're a lot more worried about what's going to happen in next year's budget."

*When this story originally appeared, it gave the impression that all caseloads at the Administration for Children's Services were increasing. In fact, regular caseworkers will not be affected by the budget cuts. Some supervisors, who had taken on only a few cases in the past, will now have a full caseload.

Dara L. Miles contributed reporting to this story.

The Mayor's Budget-Cutting Strategy

Mayor Michael Bloomberg's November budget modification is interesting for two reasons. First of all, it underscores the city's short-term budget health. Modifying this year's budget to keep it balanced remains a relatively easy task. Quite unlike the alarms spilling out of Gov. David Paterson's office, the modification for the city has no sense of immediate urgency.

(For more on the cuts and the City Council's reaction to them, see related story.)

Secondly, despite that, it is indeed full of warnings about the city's mid and long-term fiscal prospects. Further, it includes several hints of how the mayor will address big deficits in 2011 and 2012, including drawdowns from the Retirees Health Benefits Trust Fund and some less-than-progressive tax increases.

Short-term Budget Health

The city's conservative revenue estimates and the mayor's habit of building budget surpluses, then rolling them over into future years -- $6.5 billion last year alone - thus far have cushioned the economic decline's impact on city services. In fact, the November modification accomplishes its first priority -- re-balancing this year's budget -- quite easily. The budget shortfall at the moment (mostly from a drop in business income taxes) is only $300 million, a tiny fraction of a $60 billion budget, and the mayor's already implemented cutbacks this year - about 2.2 percent of agency spending - more than cover it.

The controversy has arisen from the mayor's two revenue recommendations -- rescinding the 7 percent property tax rate cut in January, worth $576 million in new revenues, and trying to cancel this year's $400 rebate for homeowners, worth $256 million. These revenues and the agency cutbacks together actually would increase the city's budget surplus for this year by nearly $1 billion. Assuming all this happens, these moves, along with other anticipated surplus and reserve funds, would put the city on the road to a 2009 surplus of over $2 billion.

The City Council usually just rubberstamps modifications. This time, though, the property-tax changes became the focus of council ire.

At the first of the hearings, on Nov. 17, council members grilled Bloomberg budget director Mark Page. During the questioning, Finance Committee chairman David Weprin produced a document -- from the mayor's office -- saying the rebate could not be canceled without council approval. Since the council has indicated it would not agree to this part of the mayor's plans, it seemed the checks would soon be in the mail.

On Wednesday, though, Bloomberg indicated he would continue to block the rebate, setting up a showdown between him and the council. By the end of the week, the mayor was striking a somewhat more conciliatory tone, opening the way to possible negotiations.

Whatever the result of this dispute, the mayor's proposed cutbacks continue his style of budget balancing thought across-the-board agency cuts. No priorities here: Not only does education share in the cutbacks - over 2 percent or $181 million this year and 5 percent or $385 million next year - but such popular agencies as the police department ($45 million this year, $167 million next), libraries (which on average will be open half a day less than they are now) and cultural organizations ($3.8 million this year, $7.2 million the next) all take hits.

The Education Cuts

One of the significant debates in current and future council hearings likely will focus on the actual impact of big cuts in education. The mayor argues that the cuts will be in administration and other non-classroom areas. The council will respond with its own list of administration cuts, saving $150 million, Council Speaker Chris Quinn said in an October speech to the business-sponsored Citizens Budget Commission

As the council and the Department of Education joust about "administration" cuts, they might look at the Independent Budget Office's new fiscal brief "The School Accountability Initiative: Totaling the Cost." The study - hampered, as the IBO puts it politely, by "the limited information available to outside agencies through the city's financial data systems" (See Gotham Gazette's "High Stakes Test" for more) - shows how slippery the definition of administration can be.

The IBO estimates that administering the schools' new accountability initiative, which prepares the school progress reports or report cards and launched in April 2006) cost $130 million last year, and will cost $105 million this year. Alternatively that $130 million could buy 13 million paperbacks at $10 each, or about 13 books for every student in city schools, pre-K to 12.

According to the education department, however, using a more narrow definition of accountability, the initiative cost only $37 million last year and $48.5 million this year.

Future Problems

The mayor's November modification takes care of the small 2009 budget deficit, and, if the council buys into the January 2009 property tax increases, also reduces the projected 2010 deficit from $2.3 billion to $1.3 billion. That too would be manageable.

Then the real trouble begins. For instance, the first major sign of fiscal stress stemming from Wall Street problems is the modifications projection that the city in 2011 and 2012 will have to make up for approximately $1.1 billion in city pension funds lost recently in the stock market.

The mayor proposes to solve the pension fund problem by taking a total of $1.1 billion from the Retiree Health Benefits Trust Fund in 2011 and 2012, a mayoral discretionary (or "rainy day") fund originally designed, as its name suggests, to meet city liabilities for future health expenses of city retirees. The fund received a total of $2.5 billion from budget surpluses in 2006 and 2007.

Both Quinn and City Comptroller Bill Thompson have in recent years proposed a legislated rainy day fund that would set the terms for a fund draw-down in a fiscal crisis, and it will be interesting to see how they respond to the mayor's sudden change in the use of that fund.

Even with drawdowns from the retirees fund, deficits for 2011 and 2012 will average $5 billion. The current modification looks ahead, and its revenue options in the modification for 2010 provide at least a hint of where Bloomberg might go with tax policy. However, his short laundry list of tax increase options reads more as a partial primer than as a comprehensive revenue plan, interesting as much for what it leaves out as what it includes.

Tax Options

The city's current four-year fiscal plan already assumes that, in July 2009, the average property tax rate will revert to its 2002 to 2006 rate and stay there. The proposed November modification, as noted earlier, would simply make the rescission effective in January 2009 rather than July.

This means other revenues will be necessary. The modification offers several possibilities to meet the 2010 deficit: three options for increases in the sales tax - the most regressive of all taxes -- and two options for across-the-board rate increases to the personal income tax.

Notable for their absence are any options to increase business taxes or to restore a more progressive personal income-tax rate structure. In a city that overwhelmingly voted for Barack Obama and, presumably, for his progressive tax agenda, including tax cuts for working and middle class families (see "Candidate Talk Taxes"), the mayor's options of 7.5 percent and 15 percent across-the-board increases in the personal income tax rate hit these same, most vulnerable of taxpayers.

Six years ago, as part of the huge November 2002 modification, the same mayor increased income tax revenues in a progressive way, by creating two temporary, three-year top rates for higher-income taxpayers. Other taxpayers' rates remained unchanged.

An across-the-board 7.5 percent increase would raise $585 million in 2010; a 15 percent increase would raise $1.2 billion. The 7.5 percent increase would cost a taxpayer with taxable income between $50,000 and $75,000 an additional $116. A 15 percent increase would cost her $233.

A taxpayer with taxable income between $75,000 and $90,000 would pay, with a 7.5 percent increase, an additional $178, and with a 15 percent increase, $356 annually.

The regressive sales tax options include increasing the city sales tax from 4 percent to 4.25 percent, raising $292 million in 2010, or to 4.125 percent, which would raise $146 million. Reinstituting a sales tax on clothing (the current exemption reduces the sales tax's regressivity) would raise $436 million.

Taking two of these options -- raising the sales tax rate to 4.25 percent and increasing the personal income tax across-the-board by 15percent -- would raise $1.5 billion in 2011, only 30.5 percent of that year's projected $5 billion deficit.

What then? The mayor in a brief statement in the modification said, "We have tried to strike a balance between increases in revenue and decreases in planned spending," so the balance in 2011 would presumably come from further unspecified (across-the-board?) agency cuts.

The mayor should be commended for providing extensive information in the November modification. The summary document alone runs 55 pages. But there is minimal explanation of the data in the summary and, more importantly, too few options and too little big thinking. In its February 2008 Budget Options for NYC, for instance, the IBO listed 29 revenue options.

The IBO lists five scenarios for the personal income tax alone. All would make the tax more progressive. The most familiar, a version of the 2002 increase, would add two top rates. A 3.9 percent rate would go into effect for joint filers with incomes of $225,000 and above and a 4.2 percent rate would kick in for joint filers with income of at least $450,000. This would raise over $600 million in 2010 and would leave the rates for working and middle-class New Yorkers unchanged, a big plus in a slumping economy.

One other big revenue producer is worth noting again, but it would require changing the conversation between mayor and council. Instead of debating how to cut $200 million or $400 million from the education budget, why not look seriously at tolling the East and Harlem River bridges? Kids vs. cars? The IBO estimates the city could raise over $800 million with a toll plan.

The pain ahead for New Yorkers is not likely to be "across-the-board," and at some point the budget decision-makers will need to set some priorities. Across-the-board tax increases and across-the-board service cuts don't meet that challenge.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â