The 2009 Budget: Drawing the Battle Lines

Say sayonara to superfluous city spending, adieu to rosy revenue projections and farewell to fat city coffers.

For the first time since 2002, Mayor Michael Bloomberg's executive budget slams the brakes on agency expenditures -- ending the spending increases of the last five years. At the same time, Bloomberg has tentatively agreed to keep the 7 percent property tax reduction for one more year and continue the $400 tax rebate indefinitely.

At City Hall on Thursday, the mayor -- dressed in a crisp blue suit and red tie -- pointed to the slips and slides of Wall Street and to gloomy economic forecasts. Those predictions, the mayor contends, cannot be ignored.

"The numbers are scary," Bloomberg said during a presentation that kicks off his formal budget negotiations with the City Council. "Wall Street, which we depend on for tax revenues, is having some serious problems."

Those problems affect city agencies, and now the mayor is proposing to slash 6.4 percent of city funded expenses in fiscal year 2009. What started as a so-called across the board cut -- which the mayor first announced last year -- is beginning to play favorites, with certain agencies and programs, like the city's Department of Youth and Community Development, slated for more cuts than a few other areas, like the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications, which is getting an increase in city funding.

The largest proposed cuts come in programs that are key City Council priorities.

Though these decreases are not definite -- the City Council and the administration must reach an agreement and pass a balanced budget by July -- you can bet this latest budget battle will be far less congenial than those of recent years.

An Overview

On Thursday, the mayor proposed a $59.1 billion budget -- a small increase from his $58.5 billion proposal released in January. The budget includes $1.3 billion in cuts for fiscal year 2009, which starts in July.

Higher than expected revenues and a 33 percent increase in foreign tourists since 2000 have provided some cushion for the city. But, according to Bloomberg, our fiscal horizons remain cloudy. For fiscal year 2010, the mayor said he expects a deficit of $1.3 billion, growing to $4.6 billion in fiscal year 2011.

Because of that, the administration plans to roll back the 7 percent tax break, passed in 2007, to raise $1.22 billion -- but not until fiscal year 2010. (Some officials see that proposal as a stretch, since next year is an election year, and politicians dislike raising taxes the year their name is on the ballot).

One official said it was not impossible, though unlikely, that the City Council would revisit the tax rate this year, depending on the economy.

"Obviously if we needed revenue we could raise the property tax by a percent or two," said the council's Finance Committee Chairman David Weprin. "The sense of the council is everyone would like to see the property tax stay in place for the most part."

In what many have termed a significant but needed cut, the mayor also proposed to extend the city's four-year capital plan to five years, effectively slashing 20 percent of the program's cost by extending proposals -- not eliminating them. The administration has not determined which projects will be pushed back and plans to release that information in September.

For the most part, the city's fiscal watchdogs saw the mayor's proposal as sound -- a realistic approach to a teetering stock market and an economy that, some analysts say, is ensnared in a recession. But critics have already emerged and are gearing up for a contentious battle over some of Bloomberg's planned cuts, particularly in education.

Wall Street Pains

While tourism continues to boost revenues, Wall Street's woes have barreled down Broadway and into City Hall. Wall Street firms lost more than $11 billion in 2007, after posting record profits the previous year, according to the mayor's office.

Because Wall Street drives the city's economy (wages in the securities industry alone account for 25 percent of city salaries), any volatility there can threaten city programs.

Much of his hour-long budget presentation was devoted to the financial sector's impact on the New York City economy. In slide after slide, the mayor reiterated Wall Street's influence, despite efforts to diversify city revenue.

"Everyone in this city should pray that Wall Street does well," said Bloomberg gesturing to a slide with his presentation's typically morose statistics.

The city's fiscal watchdogs and observers have echoed that sentiment. While little can be done about the impacts of this economic slowdown, some experts suggested the administration should attempt to limit Wall Street's impact in the future.

Nicole Gelinas, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, said the city should explore other sources of revenue, so it is not held hostage to the ebb and flow of the stock market. "A lot of this is designed on our tax structure," said Gelinas. "We could make this a lot easier if we designed a structure that attracts new businesses."

Where the Cuts Run Deep

A pillar of the Bloomberg's fiscal year 2009 budget is that no one is immune -- all city agencies must shoulder the burden of hard times, which some see as a fair approach to fiscal policy.

"From a fairness point of view, you don’t want to have any sacred cows," said Charles Brecher, executive vice president and director of research at the Citizens Budget Commission. "Everyone has to pitch in."

Although Bloomberg directed all agencies to submit approximately 3 percent cuts last year and another 5 percent for fiscal year 2009, some departments are now bearing more of the burden than others.

According to an analysis of budget documents, several agencies are seeing more than 10 percent cuts in city spending. The Department of Youth and Community Development has a 27.6 percent decrease in city spending for fiscal year 2009 compared to the projected city spending in fiscal year 2008. The Department for the Aging, Department of Cultural Affairs, Department of Homeless Services and Housing Preservation and Development are all slated for large cuts in city spending -- ranging from about 11 to 19 percent.

"Any further cuts to the Department of Aging, is serous business in my backyard," said Councilmember Vincent Gentile.

Other departments have been spared. The Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications is seeing a 20 percent increase in city funding, catapulting their funds from $202 million to $243.7 million. The increase, according to the mayor's executive budget, will go to the city's new wireless network for emergency personnel and to support the city's 311 information hotline.

Some of the rising costs, however, are out of the administration's control. For instance, the Department of Sanitation's expenditures have risen by 2 percent from 2008, which, according to budget documents, are attributed to the rising personnel and waste export costs.

Overall, some of the agencies that see large decreases in city funding may have gotten a boost in funding from the state or from Washington. Others, like the Department of Youth and Community Development, saw their federal funding actually decrease as well.

City Council tends to put a high priority on spending for community-based groups and programs that tend to get funding from the city's youth department and other departments slated for spending cuts, such as the Department of Cultural Affairs, which is facing an 11 percent cut in city spending. In the past when such programs have been cut by the administration, the council has restored their funding during budget negotiations -- a process called the budget dance. Some observers have crticized this maneuver, saying the executive branch's reductions are meaningless, since they are always restored, allowing council members to score easy political points .

"We've come a long way to ending the budget dance," said Weprin, alluding to the back and forth between the administration and the council. "It always seems to be that when there are cuts, council priorities seem to go first."

Battle Lines Drawn

One priority close to the Bloomberg administration, education, has been thrust to the budget debate's center stage. A coalition of more than 40 organizations, including the city's powerful teachers union, already is preparing to launch a publicity campaign slamming the administration for backing down on its promise to fund education.

While the city's education funding is actually up from fiscal year 2008, by about 3.5 percent, advocates contend higher costs for food, energy and the overall impact of inflation mean the Department of Education and classrooms will end up losing out. In this year's state budget, education funding saw a 7 percent increase compared to the last fiscal year.

On the steps of City Hall on Wednesday, the day before Bloomberg released his executive budget, city officials and advocates railed against the mayor -- urging him to "keep the promise" of continuing to increase education funding.

"Turn this car around," said Robert Jackson, chair of the council's Education Committee, who pledged to vote against the budget if the department's funding was not restored. "You're heading in the wrong direction. You're supposed to be the education mayor," he added, alluding to Bloomberg's takeover of the public schools.

Following the release of the mayor's budget, Council Speaker Christine Quinn called the total budget proposal responsible, but hesitated to lend her full support because of the proposed funding to the education department. "While the news of continued relief for homeowners is a positive step, the cuts to a number of city agencies, most notably to the Department of Education, are a cause for concern," she said in a prepared statement. "The council remains committed to ensuring that the necessary cuts have the least possible impact on our classrooms."

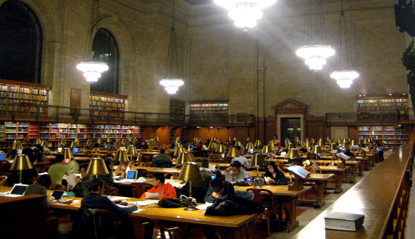

It is likely the Department of Education will not be the only battleground at City Hall this fiscal year. Libraries, which have often been the focus of the City Council and the administration's budget dance, are making an encore appearance on the dance floor.

Though the budget shows a 70 percent decline in city funding for the city's library system, funds have been prepaid to keep services up for fiscal years 2008 and 2009. But cuts elsewhere, like to the nearly $50 million needed to keep branches open six days a week, are being cited by some members as a priority.

"Sixty percent of the money added last year for six day service would be eliminated, which would in effect destroy six-day service," said Gentile, who chairs the council's subcommittee on libraries.

Other areas identified as council priorities, like the Quinn's suggested tax rebate for renters or her proposal for a sales tax free week, were left out of the mayor's budget. So far, the council's suggestions to cut spending in the administrative offices of the Department of Education and out of the classroom have not seen a response from the administration.

As the Economy Worsens: Helping People Find Jobs

As Wall Street does tailspins and foreclosure signs spring up across town, New York City's labor market can seem daunting to all but the best connected. Somehow, though, amid the economic tumult, the city government is helping thousands of New Yorkers find jobs.

That unlikely trend is a product of the workforce-development system, a network of occupational training and counseling services that has historically been seen more as a welfare institution rather than an economic force.

Since 2003, the Bloomberg administration's Department of Small Business Services has sought to transform the system, one of the nation's largest, into a market-based employment network with broad-based training and hiring programs. Under the ambitious restructuring effort, job placements per quarter have grown from about 130 in mid-2004 to some 4,300 by late 2007.

Yet some workforce experts warn that the improvements have not erased structural issues -- from entrenched poverty to limited education to language barriers -- that keep many people out of work. As the system tries to promote job opportunity in underserved communities, it must contend with a dwindling budget and a strained social service system. Reflecting a nationwide trend, the state's workforce programs lost about $130 million in combined federal and state funds between the 2003-2004 and 2005-2006 program years, according to an analysis by the New York Association of Training and Employment Professionals and the New York-based think-tank Center for an Urban Future.

More fundamentally, the system faces the challenge of promoting economic equity while encouraging business growth. Julian Alssid, executive director of the Workforce Strategy Center, an organization that has worked in 22 states to revamp workforce-investment programs, said workforce development should straddle social responsibility and economic interests. "You kind of need to balance the two," he said. "The whole idea of this is you're both getting people out of poverty and growing the economy."

Unemployed in New York

Preliminary reports from the state Labor Department indicate unemployment in the city has eased somewhat in recent years, averaging about 5 percent in 2007. But patterns of joblessness reveal stubborn inequalities. According to 2003 data for the New York metro area, blacks and Latinos had unemployment rates of 12 and 9 percent respectively, compared with about 6 percent for whites. Unemployment among black youth aged 16 to 19 approached one third, compared to around one fifth of white youth.

Meanwhile, the occupations flagged by the Labor Department as having the highest employment prospects range from mechanics and electricians to community service administrators and nurses.

The workforce-development system was built to guide New Yorkers into that hodgepodge of career possibilities. The idea is that by serving as a link between people and the job market, the government can lift up both individual households and the economy's overall health.

Market Logic

Government has often addressed unemployment and business as distinct, even conflicting, policy arenas. But the Department of Small Business Services has sought to recast workforce investment as a business proposition.

"The underpinning of everything that we've done over the last several years was to make sure that any time we are providing workforce-development services, it is in context of very specific jobs that are in demand here in New York City," said Scott Zucker, deputy commissioner for workforce development at Small Business Services.

The city has revamped its Workforce1 Career Centers, one-stop hubs for career and job-preparation services, to place more New Yorkers in "growth occupations" in sectors like health care, retail and food services. The various organizations contracted by the city to run the centers, which are now located in each borough, market themselves as a hiring resource for employers, rather than simply a way-station for the unemployed.

"We want to give the employer a value proposition that says, 'If you work with us, you'll be able to recruit a better candidate than you'll be able to recruit through somewhere else, or doing it on your own," said Tim Ford, executive director of the New York City Employment and Training Coalition, which represents community-based organizations, community colleges and other entities involved in workforce development.

To build ties with businesses, the city has launched NYC Business Solutions Hiring & Training, which identifies and pre-screens job candidates in the Workforce1 system. The program also provides grants to businesses to help fund employee training.

On a smaller scale, the city's "sector-based initiatives," backed by public and private grant money, have launched pilot projects to prepare people for jobs in the biotechnology and medical fields. One program, run by the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty, trains people for careers as certified radiology technicians, emergency medical technicians and paramedics.

Much of the growth in jobs through the workforce system has been spurred by big-name corporations, including AOL-Time Warner, FreshDirect and JetBlue. The Atlantic Terminal Mall in Brooklyn has partnered with the Brooklyn Workforce1 center to fill several hundred positions at chain stores like Target and Bath & Body Works, achieving a relatively high rate of successful applications. To take this further, the Workforce Investment Board, an oversight body with appointees from the public and private sectors, plans to establish a comprehensive workforce information service, which would offer current data about the job market and labor force to help employers and community groups track opportunities.

From the service provider's standpoint, Ford said, "it's viewing human capital as equally important as our infrastructure and other pieces of the economic development pie."

Filling Jobs

Yet workforce development's job gains are spread unevenly across the city. People with a basic education and job skills can find work relatively quickly through the system. Others -- like the immigrant with limited English skills or the single mother who reads at the fifth-grade level -- may benefit little from the programs, according to David Fischer, project director for workforce and social policy at the Center for an Urban Future. A recent study by the center found that the Workforce1 system has been able to assist just a small fraction of adults in the city who are unemployed or working poverty-wage jobs.

"If you're not basically employable when you walk into a Workforce1 center, the odds aren't very good that they're going to make you employable," Fischer said, "because the system isn't designed to do that."

While anemic funding is largely to blame, critics say, the problem is complicated by a lack of coordination among the various city agencies tied to workforce programming, such as the Human Resources Administration, which manages welfare services.

The path to "employability" has been slippery for Ketny Jean-Francois, a single mother living in the Bronx. She has been seeking steady work for about two years, but still struggles to scrape by with public assistance and a subsidized apartment.

Jean-Francois said she feels like she's fallen "way, way behind," reluctantly settling into unemployment limbo. "The longer you're on public assistance," she said, "the more you get disconnected from the workplace."

Human Resources' so-called "welfare-to-work" program has required her to take certain jobs to keep her benefits, forcing her to juggle short-term work assignments, child-care responsibilities and long-term goals. The jobs, including an office position at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and work with the sanitation department, have felt more like "serving as free labor" than preparation for real employment, she said.

The program did introduce her to LaGuardia Community College's new Workforce1 center, which offered resume workshops and job-search help. But she said the burden of her work schedule prevented her from taking advantage of those services.

The welfare regime also impeded Jean-Francois's most recent career move: job training in the nursing field. The welfare administration's review of her application for tuition sponsorship dragged on for months. She eventually found a free course on her own, but again had to petition for permission to take classes.

While she is completing her training, time constraints continue to cloud her job prospects. Her young son's subsidized daycare runs from the morning until 5:30 in the afternoon, and many of the positions she has looked into involve night shifts or odd hours.

Now an advocate with the economic-justice group Community Voices Heard, Jean-Francois hopes to forge her own welfare-to-work plan, without interference from the welfare bureaucracy.

"The people that are supposed to be helping you," she said, "they're more trying to keep you where you are."

Left Out

Many youth and immigrants remain far outside the workforce loop.

The Center for an Urban Future's study found a lack of funding for services aimed at so-called "disconnected youth," who are both out of school and jobless. Research shows that young people without work or educational credentials face chronic economic troubles later in life. Yet the center found that career-oriented services have reached only a tiny fraction of the approximately 200,000 youth in need. On top of recent deep funding cuts for youth employment services, the study cited weak coordination between youth workforce programs, managed by the Department of Youth and Community Development, and adult programs under Small Business Services.

Meanwhile, language and culture gaps isolate many immigrants from rapidly growing areas of the economy, according to Pearl Chin, executive director of the Chinatown Manpower Project, which provides training services to immigrants. To match immigrants' needs and abilities, Chinatown Manpower's training tends to concentrate on entry-level jobs in the community -- often small-scale operations with low wages and no benefits.

"A lot of times, we just have to get them in there, just so that they can work and pay the bills and feed their family," Chin said. Now, she added, facing funding cuts and an impending recession, "we cannot even continue to train and place people in those jobs that are so important to their basic survival."

Measuring Progress

So how successful are workforce programs? It depends on how you define success. The federal Workforce Investment Act sets guidelines for evaluating programs based on the number of job placements and employment retention. But critics argue these measures tend to ignore individual progress in terms of career advancement and education.

Chin said the current workforce funding structure hinders service providers from offering immigrants the sustained support they need to move toward self-sufficiency. After they initially graduate from the program, she said, "we want that ability to get them back in and train them in additional skills or English, so that we can place them in a better job, because now they have experience. We don't have the means or the flexibility to offer that additional training."

Reform advocates also want to see tighter coordination within the workforce infrastructure. Currently, agencies serving businesses, welfare recipients and youth all have workforce-related initiatives, but generally operate separately and wrestle with their own budget issues.

The city acknowledges its work is far from finished. Small Business Services is now exploring new performance measures that consider issues such as job quality and advancement opportunities. And the mayor's interagency Center for Economic Opportunity has promised to address structural employment barriers more broadly through social supports and training initiatives.

Alssid of the Workforce Strategy Center said that while the recent reforms are a promising start, the creation of a comprehensive workforce system hinges on whether the next administration can push agencies and community stakeholders to cooperate effectively.

"Ultimately," he said, "what's needed is a negotiation among all of the key actors in the city-the youth-serving agencies, the adult-serving agencies, the community colleges and so on. What can we all do together to really move large numbers of people out of poverty and into family-sustaining careers?"

Â

On the City Budget, Agreeing Not to Disagree

As national economic conditions continue to worsen, threatening federal and state budgets, prospects for balancing next year's city budget remain surprisingly upbeat. Neither the mayor nor the City Council seems inclined to fight over proposed budget cutbacks or tax decreases.

But some of the negative consequences from Mayor Michael Bloomberg's January financial plan, also known as the preliminary budget, are becoming clear. The Independent Budget Office's March analysis of the January plan and the New York City Council's recent response to it lay out both its immediate good and bad news. At the same time, the council's detailed proposal for a "rainy day fund" shows how the January plan fails to deal with the city's long-term budget problems.

The good news stems, first, from budget office and council projections that the January plan underestimated tax revenues for this fiscal year (2008) and next. The IBO estimates tax revenues this year to be $777 million higher than the mayor projected and $752 million higher in 2009. While not that optimistic, the council still projects higher tax revenues than the mayor -- $258 million this year and $392 million next. The council also has identified other revenues and savings that could provide a total of almost $1.4 billion in new resources.

The higher revenues, plus the use of big budget surpluses from previous years, means budget-balancing this year and next should not be too difficult. In fact, the council is comfortable enough with fiscal prospects to support both the mayor's retention in 2009 of this year's 7 percent cut in property tax and the $400 residential owner property tax rebate -- even though this will cost over $1.3 billion in lost revenues.

But the bad news is two-fold. First, the January plan includes some big service cuts and represents a rather dramatic reversal in such mayoral priority areas as public education, homeless services and libraries. Second, the January plan dodges the longer-term fiscal problems -- the annual deficits of $5 billion to $6 billion or more projected for 2011 and 2012 -- gaps a new mayor and a new council will face.

Across-the-Board Budget Cutting

The bulk of the mayor's budget-balancing for this year and next comes down to across-the-board cuts, 2.5 percent this year, and 5 percent next year. (The mayor's budget director suggested at a recent council hearing that Bloomberg might seek an additional 3 percent across-the-board cut for 2009.) The IBO report has an excellent rundown of what the first round of these cuts means.

In public education -- the mayor's biggest priority -- the plan cuts $180 million in the current fiscal year. Some 63 percent of that will come from individual school budgets. The impact on schools ranges from $10,000 to $447,000 per school, and averages $72,000 per school in 2008. The plan for next year is to cut $324 million, 69 percent of which will come from the schools.

The mayor could have difficulty implementing his cut in another priority area: homeless services. The city's efforts have been disappointing and, as a result, the cost of providing shelter to families has exceeded estimates. In the five years beginning June 2004, the city aimed to reduce the number of homeless families by two thirds. However, according to the IBO, the number of homeless families actually rose by 18 percent from a low in December 2005 to January 2008.

The cost of sheltering these families, projected at $314 million last June, had to be increased by $86 million in January. Although the family shelter population remains at the January level, next year's projected family-shelter costs are again $314 million. (The single adult shelter population reflects better news; it has decreased 23 percent from a high of 8,783 in January 2005 to 6,762 in August 2007.)

In both education and homeless services, the mayor has, more than mid-way through his tenure, shifted policies and administration in major ways not cited in the financial plan, or in the most recent preliminary Mayor's Management Report.

In education, regional administration has been abandoned, leading, the IBO reports, to the elimination of 472 jobs. Much decision-making has shifted to principals; new funding formulas for schools are supposed to give more dollars to more needy schools. The IBO also notes, that recent additional state education funding has been tied to new accountability requirements that the city must meet, such as class size reduction and expansion of pre-kindergarten classes.

In homeless services there are big shifts also, with services for single adults being re-structured and a new rental assistance program created with new rules and expectations. The IBO report is a first step in understanding and monitoring those shifts.

The Council Response: Cuts, Transparency and Reserves

Overall, the council supports the mayor's budget plan. Even in the face of more than $500 million in education cuts over 18 months, the council does not object to the level of cuts but only to their targets. Instead of some of the individual school cuts, the council would reduce the department's $3.17 billion in contracts with outside vendors in 2009, almost 9 percent higher than 2008's total. Bus contracts, for example, are going up over 11 percent a year, and the council urges rebidding of those transportation contracts. Overall, the council proposes a 4 percent across-the-board cut in education department contracts, saving $127 million next year.

The response does include some mild criticism of the mayor's breaking an agreement with the council to minimize friction over repeated over the mayor's repeatedly removing funding for council priority programs, knowing full well the council would restore that funding. The idea was to avoid the annual "budget dance," in which the council each year fights to re-fund favorite programs. Nevertheless, Bloomberg seems to have revived the dance. The council fears, for example, that the mayor will eliminate as much as 60 percent of the funding for six-day library services that was part of the June 2007 agreement.

What may, unfortunately, get lost in the council response is its most detailed and interesting proposal yet to create a rainy day fund, a key to preventing future budget crises. The developing flap uncovered by the New York Post last week over the council's use of non-existent organizations to hide internal budget reserve accounts is (at best) an embarrassment. It would be a shame if the revelations overshadow a fundamental question the council has had the courage to raise: how to create a reserve fund (a rainy day fund) that would become part of the regular budget process, stabilize long-term planning, and make the use of budget surpluses more transparent.

As part of its argument for the new fund, the council has a useful new analysis of recent budget-balancing and how the current use of "rollover surpluses" can distort the city's fiscal condition. Every year since 1981, the city has ended the budget year with a balanced budget as required by state law. Often, though, it has only accomplished this through the use of a previous year surplus to pay for current-year expenses.

If we look simply at current-year revenues and current-year expenditures alone (i.e., "the operating budget"), in 10 of the last 27 years the city spent more than it brought in during the fiscal year, averaging operating deficits of more than $2.6 billion a year. In 17 years there were operating surpluses, some exceeding $4 billion. What the council proposes is a state-legislated reserve fund - a "rainy day fund" - where surplus funds would be put away in good times and from which funds could be drawn in bad times.

When economic conditions improve, the council proposes the city implement a reserve fund that would "equal 12.5 percent of expenditures, thus providing a cushion for the inevitable next cyclical downturn in the city's economy." That would mean a reserve fund of about, say, $7.5 billion with a $60 billion budget, roughly what the 2009 budget will be. The council sees such a fund as giving it an equal role with the mayor in using annual surpluses: "Establishing such a fund would bring these reserves into the regular budget process and result in greater transparency," the budget response states.

The rainy day fund proposal deserves action as well as discussion. Unfortunately, action is unlikely this year. The IBO and council analyses of the mayor's financial plan suggest that both the mayor and council are anxious to keep things simple this year. New tax revenues, across-the-board spending cuts and holding on to tax cuts may well make for a relatively easy budget. The big problem, however, is that there is no commitment by either the mayor or the council to a long-term strategy for budget stability.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â