Beverage Industry Fight Against Soda Ban Just Beginning

Photo of man testifying at Board of Health hearing by Nina Goldman.

NEW YORK -- The trendsetting public health initiatives that Mayor Michael Bloomberg has successfully pushed -- smoking bans in restaurants, bars and public places, as well as health inspection ratings -- have been picked up across the country by dozens of other cities.

If beverage makers and retailers have their way, the Bloomberg administration's next big idea to limit the size of sugary drinks sold to no more than 16 ounces won't have that much fizz. What's at stake for them is not merely consumer choice but the possibility that the soda ban will start a trend that will sweep through the country.

"The New York City battle is the industry’s finger in the dyke,” said George Hacker, senior policy advisor for the Center for Public Science in the Public Interest.

Yesterday, the mayor-appointed Board of Health, which will make the decision on whether to pass the regulation, held its only public hearing on the proposal that would apply to any outlet that requires a health inspection by the city.

About 60 people spoke at the hearing held at the Department of Health in Long Island City, Queens. Eight out of 11 board members were present.

As was expected, several health experts and representatives of community organizations testified that soda is playing a large role in the obesity epidemic in America.

Several elected officials, including Council members, expressed their indignation about the decision to pass the far-reaching legislation to an unelected administrative body.

Beverage industry supporters said the plan would strip them of their freedom to choose.

Before the hearing began, Health Commissioner Thomas Farley said the proposal was "at its core" about the health of New Yorkers.

He sid if a virus was killing as many New Yorkers this year as are killed by obesity every year, people would be clamoring for government intervention. "Sugary drinks are the leading cause of the obesity epidemic in New York City,” he said.

Farley said that the limit is not restricting anyone’s rights because it still allows New Yorkers to drink as much as they want – it just limits the sizes available to them.

He said the initiative would be enforced during health department inspections and violators would face a $200 fine.

During the hearing, New Yorkers for Beverage Choice, which sprung up in response to the proposed regulation, said it delivered comments opposing the ban from 91,000 New Yorkers and 1,500 businesses.

Hacker said the industry is likely to pursue a number of avenues in their battle against Bloomberg’s policy – a public relations campaign, swaying members of the Board of Health, legislation on the state level and litigation.

In the end, the industry might not have much choice. "They may just learn to live with the new rule and hope that it doesn't seep outside of New York City," he said.

The Legal Battle

If the Board of Health goes ahead with the ban when it votes in September, it will almost certainly face a lawsuit before it goes into affect in 2013.

Farley was asked about a possible suit at the hearing and responded: “I would hope the industry wouldn’t do that. I think that simply hurts the reputation of the industry.”

Industry experts say that although it is likely many lawsuits will be filed against the ban, it isn’t clear that any particular argument will hold up in court.

Some possible challenges could include claiming the ban is "inequitable" -- as Council members Dan Halloran and Letitia James have argued. “This is going to set up an unfair competitive advantage,” James told the Gazette.

Farley argued at the hearing that the industry wouldn’t face any drastic cost increases, because the move from 20 ounces to 16 ounces is a small one and that small restaurants and eateries don’t generally serve drinks over 16 ounces.

Another argument could be that the ban violates the Constitution’s Commerce Clause that prohibits states from taking action that can hurt interstate commerce. Large soda producers could claim they are hurt by the ban.

The city's Law Department said the Board of Health was well within its authority to set the new regulation.

"The Board of Health is charged with regulating all matters that affect health. Specifically, its areas of oversight include the control of chronic disease and food service establishments,” said Chief Legal Counsel Stephen Louis. “Limiting the portion size of sugary beverages served at NYC restaurants is a valid exercise of these authorities."

The administration successfully defended challenges to its policy that banned smoking in bars and that required chain restaurants to post calorie counts in their menus. However, the administration recently lost a legal battle over graphic signs designed to show the health effects of smoking.

Michelle Simon, a public health lawyer who runs the blog “Appetite for Profit," said in the short term the beverage industry is relying heavily on public relations.

“I think the broader strategy is to send a message to other cities: "Don’t even think about this or you will be next target of ridicule," she said.

She said other cities are likely to wait and see what happens with the lawsuits against the soda ban before they more forward with similar plans, just as they did with the calorie labeling initiative that Bloomberg helped pioneer.

"Not many other mayors have the luxury of not worrying about their popularity," she said.

A Legislative Solution

City Council members, including Halloran, are consulting with members of the state Legislature for ways to override the measure.

Attacking the issue on the state level could give the American Beverage Association a shot to do what the beverage industry has so far failed to do on the city level, where it has poured a small fortune into advertising campaigns to motivate city residents to voice their opposition to the ban.

The ABA, however, has had success pouring on the lobbying dollars and influencing policy in Albany. The ABA spent $12.9 million in 2010 to successfully defeat then-Gov. David Paterson’s proposed tax on sugary beverages.

State elected officials have been cautious about taking up the cause of the beverage industry.

“We may be getting to close to Big Brother,” Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver was quoted as saying in the New York Post in June, but he quickly walked back the statement saying addressing Bloomberg’s soda ban was not a priority for the Legislature.

When Gov. Andrew Cuomo was asked about it in June on a radio show, he noted a basic support for fighting the obesity epidemic.

When asked if he would veto any attempts by the Legislature to undo the ban Cuomo said there wasn’t much point in interfering because Bloomberg’s successor will be able to review the initiative. “Then, if people really object to it, the next mayor can just undo it. I don’t think you can do a lot of harm in the interim.”

The Soda Ban and the Power of the Board of Health

Examination of diseased cattle by the members of the Board of Health, 1868.

NEW YORK – In September 2006, the city’s Board of Health announced it was weighing whether to require chain restaurants to post calorie information on their menus.

The goal of the regulation, the city’s Department of Health argued, was to address obesity – at the time more than half of adult New Yorkers were said to be overweight or obese.

The industry mobilized to stop the plan. Weeks of debate and a public hearing followed. Mayor Michael Bloomberg loudly championed the proposal and, in December, the Board voted unanimously to amend the health code with the new regulation, spurring the restaurant industry to unsuccessfully sue to stop it.

Ë™

Tomorrow, the Board of Health will hear from the public on another contentious proposal aimed at tackling the obesity crisis -- a ban on the sale of soda sizes larger than 16 ounces at restaurants, mobile carts, delis, movie theaters, arenas and stadiums or any other venue that receives a city health inspection. The proposal has stirred up the hostility of the beverage industry.

Critics and other observers say they expect the script to largely follow previous efforts to pass new regulations, with the final decision up to the Board’s group of 11 physicians, public health experts and scientists, including the health commissioner _ all appointed by the mayor.

James Colgrove, a public health historian and the author of “Epidemic City: The Politics of Public Health in New York,” said that since its beginning the Board has had “very sweeping powers” – but that it had grown increasingly influential under the Bloomberg administration.

“Bloomberg has made public health a centerpiece of his mayoral administration in a way that no other mayor has,” he said.

Some elected officials – including City Council members – and business leaders have criticized the Board's increasing importance.

City Councilman Daniel Halloran, a Republican, said the soda ban regulation was “going to be done strictly by fiat.” He added: “Any time we are going to regulate like this, I think it’s something that the elected officials need to vote on.”

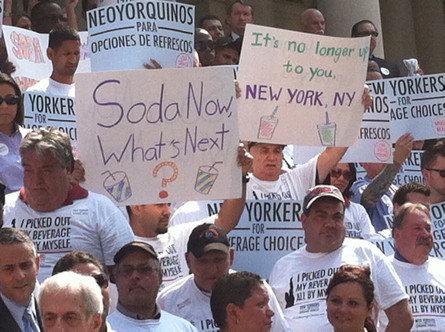

At a rally to oppose the soda ban at City Hall today, he said: "The agency's already made up its mind. Having the hearing is pointless."

A business and industry-backed group that sprung up in response to the proposal and has waged a campaign to stop it agreed that the Board would be unlikely to oppose the mayor.

“We believe that there should be a vote of the City Council. It represents the citizens of the city,” said Eliot Hoff, spokesman for New York for Beverage Choices. “The Board of Health answers to Mayor Bloomberg.”

The mayor’s office said the Board was the appropriate venue for the proposal.

“The Board of Health was designed to make public health decisions based on science, not political pressure, and that's just what it will do,” said Samantha Levine, a spokeswoman for the mayor’s office.

ATTACKING OBESITY

According to the Department of Health, more than half of New Yorkers continue to be overweight or obese – in spite of efforts by the city to encourage healthier eating and lifestyles.

Among the many indicators that obesity has reached a crisis point in the city include data showing diabetes has increased 16 percent between 2002 and 2010 and that about 5,800 deaths are linked to complications from it.

Obesity also disproportionately affects low-income and minority communities – and it is costly, with about $2.7 billion spent in Medicaid expenses in 2006.

The proposal for a soda ban came out of discussions of a task force convened in January by the mayor’s office to aggressively address obesity that involved the commissioners of 11 city agencies.

The task force announced 26 recommendations in May, including the installation of 700 new water jets and salad bars in schools; a push to create new urban agricultural sites; encouraging markets to publicize healthier alternatives to junk foods; and evaluating all city construction projects for opportunities to design buildings to encourage an active lifestyle.

But it was the proposal to establish a maximum size of sugary drinks that galvanized the attention of the beverage industry and commentators across the country.

If passed, it would apply to non-alcoholic, sweetened beverages that have more than 25 calories per 8 fluid ounces and less than 50 percent milk.

On The Daily Show, Jon Stewart joked that the proposal “combines the draconian government overreach people love with the probable lack of results they expect!" In contrast, filmmaker Spike Lee said he was in favor of it, calling obesity “a major, major problem in this country.”

The beverage industry raised the specter of overregulation – and even ran a full-page ad in newspapers of Bloomberg dressed as a nanny.

A group of 14 council members wrote a letter to the mayor on June 1 announcing their opposition. It was clear almost immediately that the Bloomberg administration would bypass the City Council and go to the Board of Health to get the ban passed.

“Many responsible, healthy, New Yorkers choose to consume soda in moderate amounts on certain occasions such as at a movie or baseball game,” the letter read. “Drinking a 20 ounce bottled soda with lunch is standard practice for many New Yorkers and does not necessarily reflect an unhealthy lifestyle.”

Councilman G. Oliver Koppell, who was among those who signed the letter, said that when a public health matter was complex and required specialized medical knowledge, it was understandable that the Board of Health would make a decision about it.

But he said that, in this case, the Council should have had some say in the matter.

“It's a decision about how far government should go in regulating people's lives,” he said. “I think it is appropriate … for a legislative body representing the people’s view to be heard.”

At a June 12 hearing, the Board of Health largely proclaimed its support for the proposal – although there were questions and some objections raised by the members.

“I just want to second the concerns about excluding juice, even 100 percent juice, and milk-containing beverages,” said Dr. Joel Forman. He said those drinks “have monstrous amounts of calories in them.”

Dr. Sixto R. Caro, another board member, said he was concerned that smaller businesses in lower-income neighborhoods would be unfairly burdened by the proposal.

In the end, the board voted unanimously to hold its only public hearing on the matter and to take comments.

Hoff, the spokesman for New York for Beverage Choices, criticized the timing and place of the meeting , saying that 1 p.m. on a Tuesday was problematic for businesses that attract a lot of customers during that time.

“It’s in the middle of the day in Long Island, Queens,” he said. “It’s not convenient for different parts of the city.”

He said hearings should instead be held in all five boroughs.

However, comments on the proposal can be made online as well.

FROM YELLOW FEVER TO OBESITY

The first Board of Health was formed in 1805, in response to Yellow Fever that had killed thousands in nearby Philadelphia. The Department of Health was created in 1870, with the Board overseeing the new division of government and the city’s powerful health code.

From the 19th to the 20th centuries, the Health Department focused most significantly on addressing infectious and chronic diseases.

The city’s health officials won pioneering battles to decrease child mortality rates, implement lead poisoning testing for children and battle AIDS.

Meanwhile, the Board’s almost unhindered oversight of the health code remained in place.

Colgrove, the public health historian, said the current focus of the Board and the Department on obesity and other so-called lifestyle diseases was appropriate.

“They are continuing the tradition that they've had all along: It's their job to protect people from what makes them sick,” he said.

Over the past few decades, the Board had on occasion become a locus of controversy – for instance, in the 1990s, a health code change allowed the Department of Health to detain those infected with tuberculosis to be detained as a last resort for treatment.

But it was not until Bloomberg came into office in 2002 that the authority of the Department of Health and, in turn, the Board, was used so assiduously – and some would say brazenly – to pass public health measures.

These have included smoking bans in restaurants, bars and, last year, parks and beaches; a ban on trans-fats in restaurants; and, of course, the posting of caloric information on menus.

The Bloomberg administration has not always gone straight to the Board, however, to change the health code, instead seeking out the support of elected officials.

But while the City Council could, in theory, pass some of the same regulations to protect the public health, it might behoove the mayor and health officials to stick to the Board.

“Strategically, you might say it is in the city's interest to do it through the health code because it is easier,” Colgrove said.

____

Nina Goldman contributed to this report.

Bronx senator's health quest

Visitors to state Sen. Gustavo Rivera’s Facebook page have become accustomed to seeing updates about the number of steps the Bronx politician has taken on a particular day.

On Dec. 9, 2011, for instance, he posted an update notifying friends that he had taken 698 steps over 11 minutes at 11:35 a.m. And, on Dec. 27, 2011, he walked 9,456 steps over 125 minutes at 9:40 a.m.

The 6-foot-2 Rivera, who is now down to 270 pounds from a high of 299, wasn’t always so worried about his weight.

But just after his election in 2010 in which he beat recently convicted former state Sen. Pedro Espada Jr., the Robert Wood Johnson foundation released a study that found that Bronx County was the unhealthiest in the state for the second year in a row. Not only was the Bronx the state leader in smoking, obesity, physical inactivity, excessive drinking, teen birth rates and even STD infections -- it also had a higher average number of premature deaths per 100,000 people.

Rivera decided he better start setting a better example by getting more exercise and eating better, all the while documenting his quest to slim down in the public eye.

“It was hard at first,” Rivera said. “But if it takes some fat guy to get up there and tell you his weight to get people thinking about the little changes they could make in their life then it’s worth it.”

It’s not just a personal quest to get healthier. He has also made improving health in his district and the state cornerstones of his policymaking.

This spring, Rivera is introducing a package of health bills he calls “non-partisan” and “commonsensical.” They include a bill to amend state laws to ban smoking 100 feet from the exits or entrances of any public or private educational institution and another that would mandate higher nutritional standards for any food marketed at a child by the inclusion of a toy.

No Smoking Near Schools

This week, the bill that would ban smoking 100 feet from the exits or entrances of any public or private educational institutions made its way out of the state Senate health committee. A vote on the bill could be imminent.

Current state law bans smoking inside and on the grounds of public and private schools, day care and vocational schools, but does not specify a protective area around entrances. The health department would enforce the new law Rivera has proposed; violators would be fined up to $2,000 per violation.

The Assembly’s health committee is expected to review the bill in two weeks. “I can’t imagine anyone would oppose this. This is about smoking near kids. It is a very sensible bill,” said Assemblyman Jeffrey Dinowitz, the bill’s sponsor in the Assembly.

Rivera said he recently took a walk around the Bronx with school kids to take a look at cigarette advertising from their perspective. He said he saw a lot of advertisements in neighborhood delis directed right at their eye-level.

The Partnership for a Smoke-Free City collaborated with Rivera on the legislation and other community efforts.

“He has been a tireless advocate for the health of Bronx youth and all Bronx Residents,” said David Lehmann, the Partnership’s Bronx Borough manager.

Food Marketed At Children

Rivera has also introduced legislation that has come to be known as the “Happy Meal Bill,” which would mandate higher nutritional standards for any food marketed at a child when accompanied by a toy.

Assemblyman Felix Ortiz, a fellow Bronx politician sponsoring the bill in his chamber, said he thinks the legislation is important for every community in the state. “This obesity problem does not discriminate against age or ethnicity,” he said. “Corporate America has to have more of a conscience about what it supplies and parents need to be responsible as well.”

With 17 percent of American children now considered obese, both Rivera and Ortiz say the cost of treating the health problems associated with childhood obesity are skyrocketing. Nationally, the annual cost of providing inpatient treatment to obese children increased from $125.9 million in 2001 to $237.6 million in 2005.

The bill, like others being weighed or passed around the country that seek to either ban toys or somehow regulate how food is marketed to children, faces opposition from food companies, including McDonald's.

“The issue is much more complex and we are committed to giving families choices," said Cheryl Forsatz, a spokeswoman for McDonald’s.

Rivera’s bill sets specific guidelines for any meal marketed with a toy. A restaurant may only offer an incentive item in combination with the purchase of a meal when the meal is less than 500 calories; has less than 600 mg of sodium; and derives less than 353 of its total calories from fat, less than 10 percent of total calories from saturated fats or less than 10 percent of calories from added sugars. It also must contain 1/4 cup of fruits or vegetables or one serving of whole grain products.

If the restaurant fails to meet the standards, they would be forced to remove the incentive item. First time violators would face a fine of between $200 and $500; repeat offenders could face fines up to $1,500.

So far, the only legislator to voice opposition to the bill is state Sen. Ruben Diaz Sr., also of the Bronx.

“Parents struggle to do what’s best for their children, and at least so far, in this country parents are not dictated to by local elected officials about how to feed their children,” Diaz wrote in an email newsletter. He questioned the right of elected officials to “tell moms how they should feed their children.”

“If parents want to feed their kids horrible stuff, god bless America, they can do that,” Rivera responded. “But we know kids develop their eating habits early on and they should be given the chance to eat healthy.”

Transforming Bronx Health

Dinowitz said he attributes the Bronx’s position as the unhealthiest county to a number of factors. “There is the economics, we have certain facilities that are not conducive to health, we have all the highways and waste transit,” he said.

Rivera agrees and said that as much as he is focused on educating Bronx residents about what they can do as he is working to fix things they may not have as much control over.

“We have two tactical strategic goals,” Rivera said. “The first is to start being better educated overall. But we need to make sure we have access to fresh fruits, access to free or low-cost places to exercise, low cost healthcare. We need to minimize pollution that raises our asthma rates.”

In June 2011, Rivera partnered with Bronx Borough President Ruben Diaz Jr. to launch the Bronx Changing Attitudes Now Health Initiative, bringing together members of the public with health organizations, providers, activists and community centers, with the goal of promoting healthy routines and setting personal health goals.

Rivera’s staff also worked to identify the farm stands and green markets in his district and sent out a flyer with the locations while inviting constituents to come meet him at certain times to talk about health. He hopes to utilize city funding to bring more green markets and vegetable stands to the district. His office is also working with beverage companies to provide the borough with healthier options, lower calorie drinks and more water.

“It takes all these things happening at the same time,” Rivera said.