Mayoral Hopefuls Speak Out On Public Health

NEW YORK — Public health under Mayor Michael Bloomberg has largely come to be equated with smoking and trans-fat bans, calorie counts on menus and a limit on the sale of large, sugary drinks.

Candidates who hope to succeed Bloomberg, however, will be challenged with helping to rehabilitate public hospitals following Superstorm Sandy, a looming $3 billion city budget gap the could curtail spending and questions over what federal health care reform will mean for the city.

At a forum on public health on Wednesday, four mayoral hopefuls spoke about what they see as the critical needs of the public health system, agreeing that too many of the neediest New Yorkers remain without proper health care.

Democrats John Liu, William Thompson and Sal Albanese, as well as Republican Tom Allon each took turns on the stage at Long Island University in Brooklyn. The two expected frontrunners for the party nominations for mayor, Democrat Christine Quinn and Republican Joe Lhota, did not attend.

Liu, the city's comptroller, said he wasn't optimistic that the city could make up for a reduction in federal dollars caused by the Affordable Care Act. “There's a big question mark around Obamacare," he said.

There is money to be found in the system to pay for improvements, but it might well take more audits to find it, he said. Liu pointed to numerous cases of health care fraud over the past few years which found the misappropriation of hundreds of millions of dollars.

Attacking corruption was something of a refrain for each candidate. Tom Allon, the sole Republican candidate to speak at the forum and owner of Manhattan Media, referred to Pedro Espada Jr, a former state senator who was convicted of looting hundreds of thousands of dollars from the Bronx health care network he founded. “That kind of stealing is probably still going on elsewhere in the city,” added Allon.

Fixing the city's hospitals is "a question of management,” he said.

That means being “smarter about where our dollars are coming from,” said former New York City Comptroller Bill Thompson, who held the office from 2002 until 2010.

Thompson, who previously ran for mayor in 2009 but lost to Mayor Michael Bloomberg by about 4.5 percentage points, took aim at his former rival by saying the problem of finding money in the budget was exacerbated by unresolved labor disputes with city employees.

Calling it "irresponsible" not to have set aside funding to cover those projected expenses, and with the budget hole fix still unclear, paying for better public health would be an immense challenge, Thompson said. Still, public health remains a priority.

"There are ways of saving money without sacrificing care," he said, noting that the hospital's network system needed to be revised to create a more efficient model. He said that as comptroller, he took the "unusual" step of looking into waste in the public health system.

While the short-term fixes were unclear, the candidates pointed to a common long-term solution: a preventative approach to addressing illnesses. By better educating children and by identifying early warning signs of disease, candidate Sal Albanese, a former Councilman who held office until 1997, suggested the city could save money going forward.

"We need pediatric wellness clinics" for those who cannot afford a doctor's visit, as well as "nurses who can go into a person's home" to help care for newly-born children as young as three months, he said.

Albanese, who previously worked as a health education teacher in the New York City school system, said he received his masters degree in health education free of charge, courtesy of the state of New York in the 1970s, when the state needed to encourage more qualified educators in the field. This kind of future planning should be continued, he said.

A model for the integration of health services in a school system, added Thompson, could be Cincinnati, which incorporates medical education and check-ups. This, he says, helps catch mental illnesses and diseases like diabetes, which may go undetected by parents.

While candidates mostly lauded Mayor Michael Bloomberg's record on public health, Thompson tried to take the fizz out of the soda ban, saying it was "good P.R., but a missed opportunity to do more for public health." That would include addressing the unequal distribution of parks and recreation areas available to the neediest.

Further, nearly all the candidates agreed the mayor erred in moving away from community-based organizations to address health care needs. Having CBOs could eliminate cultural in-sensitivities and other onerous burdens that would be placed on the patient.

By consolidating in the hopes of saving money, said Thompson, Bloomberg's policy left many underserved communities behind. “Health services should be closer to a community,” he said to applause.

CBOs would mean easing language restrictions, which Liu said can result in the death of patients. “I have constituents come to me and say a loved one died because they couldn't explain their health problem,” he said. Liu said he fought for equal language access as a councilman.

Sponsored by 22 organizations, ranging from the Commission on the Public's Health System to New York Immigration Coalition and the New Yorkers for Accessible Health Coverage, the forum offered a handbook to the attendees and candidates that highlighted key public health issues facing the city.

“The answers to all your questions are probably in this book,” Liu joked.

Jackie Vimo, a representative of the New York Immigration Coalition and forum member, called the book a “to-do” list for the next mayor of the city.

Those needs include identifying focusing on immigrant access, chronic conditions, and helping individuals with disabilities. The group further highlighted social determinants that factor into health, such as poverty, nutrition, lack of exercise, and low paying, potentially dangerous jobs that can pose a challenge to finding the time to see a doctor, she said.

According to the Immigration Coalition, almost 2.5 million residents are designated as “medically underserved,” further underscoring the challenge to serving them.

Judy Wessler, director of the Commission on the Public's Health System, said the problem was complicated by a system operating on "fuzzy math."

Hospitals that serve many Medicaid patients do not see enough revenue to remain open without public assistance, she said, but that assistance, which comes from the state, is often misused.

The next mayor needs to help address this, she added.

Hurricane Sandy further exposed the consequences of limited hospital options in cases of emergency when a handful of hospitals were forced to evacaute. Maimonides Hospital took on about 100 more patients as a result of Coney Island Hospital's closure. New York University's failed generators forced the evacuation of hundreds of patients the night of the storm, with some 200 patients transported to five hospitals throughout the city. In addition, the Bellevue Hospital Center emergency room and the VA New York Harbor Healthcare system remained closed for weeks after the storm.

"We had no plan for Sandy," Albanese said. "We're a crisis oriented society."

___

Photo by Matt Hunger

What Is Going On With City Council Redistricting? A Primer

NEW YORK — The once-a-decade process of redrawing the City Council's district lines is downright confounding to most people. The process became even more confusing after the commission responsible for drawing the lines pulled its final draft plan from consideration in December.

That set the schedule back by several weeks and led to new public hearings this month. The first is scheduled for tonight. To help you get caught up on what all of this means, we've put together this handy primer on Council districting. Take it to the meeting and share it with friends.

Why does redistricting matter?

When Council district lines are finalized in a few months, they will not change again for a decade.

What residents of tightly-knit communities across New York City might not realize is that if they depend at all on public and private services, the Council members who represent them and the shapes of the districts they reside in matter far more than they think.

Unlike state representatives, Council members can dispense thousands of dollars in discretionary funds to community programs and capital upgrades like hospital and street repairs. The funding, often characterized as pork, can still allow local nonprofits to thrive. A Council member who is actively engaged in representing their community can stave off firehouse closures, help restore a crucial bus line or repair a library.

When neighborhoods or communities of common interest are united in a single district, a Council member is more likely to pay attention to them. If a neighborhood is carved up into several different districts, it becomes secondary or tertiary to multiple Council members. This means it can lose out on crucial funding.

For example, activists in the Queens neighborhood of Woodhaven are worried because the current map proposal divides Woodhaven in two districts and places residents with Council members they have not necessarily worked with before. Residents of Woodhaven are looking to avoid what was the decade-long fate of Richmond Hill, a neighboring community that was split among four different Council districts.

While Richmond Hill’s immigrant population continued to burgeon and reshape the area, it has lacked community centers, after school programs and even garbage cans on one busy avenue because there was never one Council member focused on their priorities. Even the most well-intentioned Council member is most likely to focus on the primary portion of their district and not a piece located on the outer edge.

What is the Districting Commission?

The 15-member Districting Commission is the body appointed by the mayor as well as the majority and minority caucuses of the Council to redraw the City Council lines. Two members of the commission, Republicans Tom Ognibene and Frank Padavan —both from Queens — are former elected officials. The commission also has an executive director and staff.

After finalizing its plan, the commission must send it to the Council for a vote. The U.S. Dept. of Justice must ultimately approve the district lines that the commission draws.

Some have hailed the city’s Districting Commission as a vast improvement over other mechanisms for redistricting, like on the state level, where elected officials can draw their own districts to protect themselves from challengers. While the City Charter rigidly defines the boundaries of City Council districts, state Senate and Assembly districts can end up resembling bizarre puzzle pieces or Rorschach blots.

But good government groups and political insiders have questioned the independence of the city’s commission.

“What we’ve seen actually is that the commission acts as a layer that sort of clouds the transparency of the process,” said James Hong, a spokesman for the Asian American Community Coalition on Redistricting and Democracy, a coalition of 14 Asian-American advocacy organizations that have fought for fairer minority representation in city and state districts. “When you compare it to the state process, there it was heavily partisan and there was really a lot of conflict of interest — we don’t agree with it. However, it was very clear who was in control of the process.”

Hong said the Council redistricting process is “just as politicized,” but that “it’s hard to know exactly who is doing what. There’s an opaqueness from the involvement of the commission.”

One council member, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said Carl Hum, the executive director of the commission, met with council members to ask them what proposals worked for themselves and the community. Members of Quinn’s staff contacted council members during the redistricting process to discuss their districts, the council member said. However, it is not unusual for elected officials to weigh in on districting matters. The commission allows elected officials to testify at public hearings.

At a meeting of the reform-oriented New Kings Democrats on Jan. 3, a representative of the commission, Jonathan Ettricks, defended the commission’s work.

“This is a process where anyone can have their voices heard,” Ettricks said. “Elected officials are people … If they want to try to have their own interests realized, certainly they are able to do that.”

An issue that the New Kings Democrats brought up was the lack of public recording of meetings between members of the Council and the commission. Testimonies at public hearings are readily accessible but individual meetings between commission members and Council members are not immediately available to the public. This information is available by Freedom of Information Law request.

Ettricks agreed that information on those kinds of meetings should be more readily available in the future.

“I think that’s an issue that has come up and there are some elected officials who have even raised that issue publicly and perhaps it’s something that should be done going forward but it’s not something that was incorporated into the process,” he said.

Lincoln Restler, a member of the New Kings Democrats and a possible candidate for City Council, said he had a lot of concerns about the fairness of the redistricting process.

“I think even the redistricting commission representative recognized opportunities to increase transparency and ensure a more fair outcome for neighborhood residents is very much possible and in fact needed,” Restler said. “This commission has primarily focused on protecting the interests of incumbents and that fails to meet our expectation for an independent redistricting process that represents the interests of New York City residents.”

Why new public hearings were called

The process for redrawing district lines was supposed to be done by now.

The Districting Commission had turned in its final draft to the City Council for consideration on Nov. 16, when news broke three days later that a change to the Brooklyn lines would have given disgraced Democratic powerbroker Vito Lopez a boost in a possible bid for a Council seat in the 34th District.

A Lopez ally, term-limited Councilman Erik Dilan, allegedly requested the change. Outraged, Council Speaker Christine Quinnurged the commission to withdraw the map and move Lopez’s residence back out of the 34th District, though she was initially told on Nov. 16 that the panel had no power to tweak district lines without the City Council rejecting them first.

The reported ploy to boost Lopez’ chances was especially bizarre because a redistricting year has far more lenient residency requirements.

Hum admitted at a meeting in December that public opinion weighed on the commission’s decision to withdraw the maps.

“Certainly, there was a lot of public concern about that and we responded to that,” said Hum when asked if the press reports about Lopez’s residence being drawn into the 34th District influenced the commission’s decision. “The same way we responded to requests for additional hearings.”

New public hearings were something that good government groups were calling for long before the Lopez fallout. They had lamented that the public did not have a chance to comment on the revised version of the maps that were forwarded to the Council.

“I think that a third round is a good thing,” said Susan Lerner, executive director of Common Cause New York. “The timeframe did not allow the commissioner and the staff to put out their final recommendation for the public to make comments on. This third round will allow that to happen.”

Lerner admitted she was not “enthralled” with the procedure, but said she believed the outcome was the correct one.

Wait a minute, what is this about Lopez?

Lopez, a state Assemblyman representing the neighborhoods of Williamsburg and Bushwick, was accused of sexually harassing staffers earlier this year in a scandal that led most high-profile politicians in the city, including Quinn, to distance themselves from the longtime Brooklyn party leader. Lopez currently faces an ethics inquiry.

On Nov. 29, Council Speaker Christine Quinn sent a letter to the chair raising concerns about some of the lines, in particular a change that would have placed Lopez in the 34th District, where he was mulling a council bid.

While lauding the commission's work in her Nov. 29 letter to Chair Benito Romano, Quinn requested the lines be withdrawn and that a new series of public hearings be convened.

"Notwithstanding your efforts, there is still a need for more public participation," she wrote.

During the meeting in December, Romano agreed with Quinn that the best course was to withdraw the maps and hold a new round of hearings in January.

"I believe that we all agree that by maximizing public input, we will ensure the creation of a district plan that better reflects the complexity and diversity of our city," he said, according to a transcript of the hearing.

He said that the commissioners had communicated their interest in more public comment when they sent their plan to the Council on Nov. 19 for a vote, but also expressed concern that under the City Charter there was little legal recourse or time to do so.

The Council would have had to vote to reject or accept the lines by Dec. 10, or they would have lapsed into law, leaving little time in between to hold public forums.

Besides the interest in more public input, Romano said that Quinn's request "left open the possibility that the City Council would not vote to reject the plan" if it was not withdrawn before the Dec. 10 deadline. He added, "I believe that further underscored the need for action on the part of the commission."

Romano said he anticipated the next round of public hearings and meetings by the commission could be wrapped up by February 2013, with a new revised district plan delivered to the Council for a vote. The Council would then have three weeks to adopt or reject the plan.

"We would hope to have a final plan adopted prior to March 5, 2013," he said, according to a transcript.

To make matters even murkier, after withdrawing the map, the commission voted to agree to two changes to the plan that had been submitted to the Council and will now be the subject of a new round of public hearings.

At least one commissioner said he was concerned that the decision to withdraw the map and then vote to update it would lead to more confusion by the public rather than be seen as an effort to create more accountability of the process.

“It’s a question of perception I’m concerned about, misleading the general public who will not understand everything that was spoken here today," said Padavan, a former Republican state Senator, who voted for the withdrawal of the map but abstained from the vote on making public the two changes to the plan.

Was the process skewed to protect incumbents and what effect might it have on this year’s election?

Hum has said that “incumbency protection” is one of the factors the commission considers when drawing new districts.

And, as Gotham Gazette Demographics Columnist Andy Beveridge wrote in November after analyzing the final draft plan: “Overall the plan continues the time honored tradition of incumbency protection, but it is worth noting that such concern for incumbents has been found by the Supreme Court to be a legitimate basis for redistricting.”

The change in the schedule of when the districts will be voted on also benefits incumbents, because challengers will have less time to know which districts they will be running in, especially if a June primary date is scheduled.

All of this could have ripple effects for the city as a whole, said Rachael Fauss, policy and research manager for Citizens Union (the sister organization of Gotham Gazette).

“One concern is that a candidate who is not an incumbent may not know their district as well,” Fauss said. “It may be helpful to lessen the petition requirement and make it easier for the candidate to get on the ballot. The BOE (Board of Elections) is going to have to deal with everything more quickly — they have to draw new election districts … It’s still an open question if the BOE has enough time to do everything.”

But not all incumbents got everything they wanted. For instance, Republican Councilman Dan Halloran, saw his 19th District in eastern Queens altered at least somewhat to his liking. But not northern Flushing, which was excised from his current district.

“The Commission took appropriate action by withdrawing the proposed lines from the Council,” said Halloran in a statement. The councilman had attended both public hearings in Queens and submitted written testimony. “I am hopeful that deliberations and the next public hearing will lead to the restoration of northern Flushing to the 19th District, so that the single-family homeowners in that area will continue to have a voice in the Council and not be disenfranchised.”

Civil rights organizations have been vociferously opposed to some of the commission's lines

The Asian American Community Coalition on Redistricting and Democracy, the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund and LatinoJustice PRLDEF were at the forefront of a push to ensure that the new district lines would increase the voting power of the burgeoning minority populations of New York City.

The groups, among others, put forward their own redistricting proposal, called the “Unity Map.” The Districting Commission must draw lines that comply with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which was created to protect politically-cohesive minority groups from having their voting power diluted.

Section 5 of the act applies to jurisdictions in specific states with histories of discriminatory electoral practices. With its large minority populations, Brooklyn, Manhattan and the Bronx all fall under Section 5.

In Brooklyn, civil rights advocacy groups have argued Bensonhurst, with its booming Asian population, is unfairly cleaved into four different districts. ACCORD took further aim at Queens, arguing the neighborhood of Oakland Gardens, home to a growing Korean population, should be united with neighboring Bayside.

Briarwood, another Queens neighborhood home to a growing South Asian population, was split in two in the latest map proposal. ACCORD wants the Queens neighborhoods of South Ozone Park and Richmond Hill, also South Asian in make-up, united more fully into a single district.

Jerry Vattamala, a staff attorney with AALDEF, questioned why commission wasn’t being more fully responsive to these concerns.

“How many speakers said Oakland Gardens should be with the rest of Bayside? Where are those changes?” Vattamala asked. “I think there’s a lot of politics involved here with this, quote unquote, independent commission; there’s this sort of black hole. We don’t know what the real reasons are for why the maps are drawn, why changes are being made, who’s really calling the shots.”

He added, “One thing is clear, it isn’t the public.”

In Manhattan, Councilwoman Melissa Mark-Viverito slammed the commission for removing a chunk of East Harlem from her district and adding thousands of voters from the Bronx and move Randalls Island out of her district to one in Queens.

Mark-Viverito and residents have accused the commission of playing politics with their neighborhood. “They’re carving East Harlem up like a turkey, all for some other political end,” Mark-Viverito told Daily News columnist Juan Gonzalez in a story published over the weekend. But Hum has disputed those allegations.

____

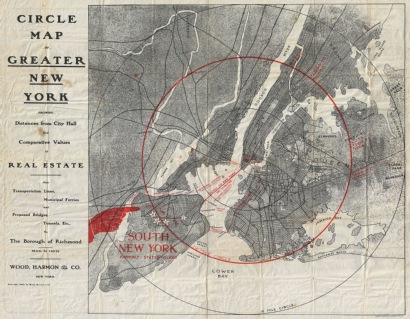

Additional reporting by Cristian Salazar. Image of 1906 Wood Harmon Map of New York City courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

How Hurricane Sandy Upended Politics As Usual in Albany

ALBANY, N.Y. — With the power in the State Senate hanging in the balance after last week's election and the impact of Superstorm Sandy overshadowing the civic debate, the political calculus in Albany has shifted.

Where only a few weeks ago lobbyists and policy makers were debating the possibility of a special session of the State Legislature that would address campaign financing, the minimum wage and marijuana possession laws, they are now talking about how the government can respond with smarter policies to lessen the impact of future super storms.

“Rebuilding becomes the focus now,” said Russ Haven, legislative counsel at the New York Public Interest Research Group, in an interview this week.

He added that legislative pay raises that had long been rumored as a focus of a special session will be “a lot harder to do” now that Sandy has added to the state’s budget shortfall.

Haven and other political observers are still eyeing the outcome of key races to see whether they shift the State Senate to the Democratic Party. The Senate is currently split 33-29 in favor of the Republicans.

Even if the Democrats do eke out a majority, it could be rendered almost meaningless. The Independent Democratic Conference, a rogue group of four Democrats led by Bronx State Sen. Jeffrey Klein, is in a position to play the spoiler and could decide to align with the current majority of Republicans. Newly elected Brooklyn State Sen. Simcha Felder has said he will caucus with the Republicans. And, perhaps most importantly, the Democrats have long fallen out of favor with the state's popular governor.

“The governor, given his popularity, institutional powers and demonstrated capacity for negotiating has the upper hand one way or another," Haven said, adding that Gov. Andrew Cuomo and the IDC are also politically aligned. “The IDC is in tune with the governor’s agenda. They are fiscally conservative and support more liberal social issues.”

Former Gov. David Paterson wrote in The Times Union this Sunday: “Rising above all this political uncertainty is one simple fact: No matter what happens come January, Gov. Andrew Cuomo will end up a winner either way.

If the Republicans return to power, the governor will still have an ally on his important economic agenda of job creation, low taxes and regulatory relief. If the Democrats win, Cuomo will be able to pass the social agenda that has been stymied by the Republicans: minimum wage, campaign finance reform and more intelligent marijuana possession laws.

Cuomo has tried to stay above the fray, instead focusing his political energy on the storm cleanup.

"The Assembly will pick a leader, and the Senate will pick a leader. And I have no intention of getting involved in either situation," Cuomo said at a press conference last week, while underscoring that he thought Democrats learned a lesson the last time they were in control of the Senate. "I think they learned the hard way. The Democrats were in power. The Democrats then lost power because of the dysfunction and I think they learned that lesson the hard way."

In 2008, Democrats took control of the Senate Majority, but first they had to win the support of the self-titled Four Amigos, comprised of Sens. Carl Krueger, Ruben Diaz, Pedro Espada and Hiram Monserrate. The four realized the Democrats needed their votes to elect a majority leader held out until they received the terms they wanted to support Sen. Malcolm Smith. The men won prominent committee seats, staffing and, according to some, received guarantees from Smith about what legislation he would introduce. In June 2009, Espada and Monserrate got a better offer from Sen. Dean Skelos and launched the coup that paralyzed the Legislature for months.

But while no one in Albany wants to see a repeat, those groups who have seen their agendas sidelined by the Republicans are hoping the Democrats gain the Majority.

Michael McKee, the treasurer of Tenants PAC, a political action committee dedicated to keeping apartments affordable for New Yorkers, had trouble sleeping on election night as he watched the results come in.

That's because the group he works for had poured thousands of dollars into the campaigns of Senate Democrats across the state: They had given $ 6,000 to Cecelia Tkaczyk in the 46th Senate Districtand held a fundraiser for her; another 10,300 had gone to George Latimer in eastern Westchester County; $7,000 to Queens Sen. Joe Addabbo; $4,000 to Justin Wagner; $6,000 to Nassau County's Ryan Cronin; and $2,000 to Ted Obrien.

One after another, McKee watched as the candidates they supported won their races or edged ahead as recounts loomed. "I was so excited, I couldn't sleep," McKee said.

But in the days since election night, McKee's fervor has turned to caution.

For years, Tenants PAC has worked with one goal in mind: Elect as many Democrats as possible to the State Senate who would be willing to help to pass legislation that protects housing for working class New Yorkers.

“We worked very hard to help the Democrats win the Senate. And we also helped upgrade the Senate. We are proud of that,” said McKee, who said he gave Tkacyzk a few hundred dollars or his own money. “We are proud of replacing Sen. Pedro Espada with Sen. Gustavo Rivera. But if the Republicans or Jeff Klein is in charge, we have no chance. I would rather see them remain in the minority for two years rather than make a deal like last time."

Business groups are worried about what the Senate Democrats might mean for their agenda.

"I didn't know whether to chuckle or cry," Michael Durant, New York state director of the National Federation of Independent Businesses, told Crains New York. "Unfortunately, it appears in some races that are essential to the Senate that economic development and jobs were not the central theme."

Brian Sampson of Unshackle Upstate, a conservative business group, told the newspaper that life would be a bit more difficult with a closely split Senate.

"I don't care if you're the business community or the ultra-progressive left," he said. "Any bill that has any controversy to it is just going to take that much longer to get to the floor. And once it gets there, you're going to have to work that much harder to get it passed or get it defeated."

A number of Albany insiders say Senate Democrats realize that they have to appeal to businesses interests and upstaters — especially because the seats they gained this year and seem poised to gain are upstate and to keep those seats they will need to tend to their issues.

Sen. Michael Gianaris, head of the State Senate Democratic Campaign Committee, has said repeatedly that his conference is committed to promoting a “pro-business” agenda.

The United Federation of Teachers and New York State United Teachers also publicly backed a number of Senate Democrats and have a lot invested in the outcome of the battle for control of the Senate. NYSUT reportedly spent $500,000 to help Addabbo retain his seat.

Teacher unions are very interested in countering Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s plans for school reforms and his continued push for concessions from unions. Clearly they felt a Democratic Majority in the Senate would help blunt Cuomo’s agenda, but it isn’t clear if a coalition government would help them at all.

But it isn’t just those who gave money who are concerned with who will control the Senate when session starts next January.

Gene Russianoff, of The New York Public Interest Group’s Straphangers Campaign, says funding of the MTA is also very much at stake. If Senate Republicans get what they want, the mobility tax on areas served by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority would be completely repealed.

“It is widely perceived among Republicans that it is a highly unpopular tax. They eliminated it last year for some small business and it cost the budget$300,000 that Gov. Cuomo found the cash to replace,” he said. Russianoff noted that Democrats passed the tax by party line in 2009, so it is likely that the tax battle would split down party lines.

But Haven, of NYPIRG, said that post Sandy, the people will want to be sure their leaders are focused on fixing things quickly.

“From now on, I think we are going to look at everything the state does through the lens of how we deal with disasters," he said. "People want a smart government that is ready to deal with how we move forward.”