National Survey on Child Poverty

Children in New York are better off financially than they were two years ago, according to a national survey released in early November by the Urban Institute and Child Trends of Washington, D.C.

Fewer children live below the federal poverty line, fewer families report having trouble putting food on the table, and fewer children live in single parent homes.

However, New York families still lag behind the rest of the nation in obtaining economic stability, and there is still a large segment of New York State children living in extreme poverty. Furthermore, children as a group are still poorer than other Americans.

"Although we found reductions in the gap between low income children and the rest, there still is an alarming gap," said Sharon Vandivere, of Child Trends, and one of the authors of the study.

The survey of 42,000 households across the country produced state-specific results for New York as well as national results, making it possible to compare the economic well-being of New York families to that of families nationally.

Among the findings:

- The child poverty rate declined in New York, but a large portion of children remain very poor. The percent of children living in poverty slipped from 25 percent in 1997 to 22 percent in 1999. Children in poverty live in families that have less than the amount the federal government identifies as the minimum annual income needed to avoid shortages of basic necessities ($13,133 for a family of three). Nationwide, the rate of child poverty dropped from 21 to 18 percent over the two years.

- The poverty rate is much higher for children than adults. In New York 13 percent of adults New Yorkers live below the poverty line. Nationally, 11 percent of adults do.

- Nearly half of New York children, 44 percent, reside in low income families. These are families with annual incomes of less than 200 percent of the federal poverty threshold. There was no change in the size of this group in New York from 1997 to 1999. Nationally, the percent of children living in low-income families dropped from 43 to 40 percent.

- New York single parents made large gains in employment from 1997 to 1999. The employment rate for poor single parents in New York jumped from 50 percent in 1997 to 62 percent in 1999, an increase that dwarfed employment gains made by parents in other states and in other income categories.

- Low income families found it easier to afford food in 1999 than in 1997. 57 percent of low income families ran out or nearly ran out of food at least once during 1997, compared to 50 percent in 1999.

- The proportion of low income youngsters living in single family homes dropped from 1997 to 1999. In New York, the percentage fell from 51 percent to 47 percent, and nationally, from 44 percent to 42 percent.

The Urban Institute and Child Trends teamed up to conduct this survey in an effort to measure the impact of welfare reform on family well-being. The team did an earlier survey in 1997 and a third round is planned for 2002.

Child Trend's Vandivere said the survey does not show whether children are being harmed or helped by welfare reform. "Family structure and poverty rates are targets of welfare reform but we cannot assume a causal connection between reforms and reductions in poverty or the other things," she said. "Changes in these things could also be due to the fact that this is the longest economic expansion in the country's history."

Peggy J. Farber is freelance journalist specializing in children's issues. Her reporting on conditions of NYC children has appeared in City Limits Magazine as well as on National Public Radio.

Election Special-The Real Tech Issues, from Privacy to Copyright to Sales Tax

Hillary Clinton and Rick Lazio were rudely ushered into the Information Age, when the moderator during their second debate asked them their position on federal bill 602p, which she explained was pending legislation that would allow the U.S. Postal Service to charge five cents tax on every e-mail sent. This would make up for all the lost revenue from people who have been e-mailing to each other instead of mailing letters.

Lazio was downright emotional. "I am absolutely opposed to this," he said. "We need to keep the government's hands off the Internet." Clinton was also opposed. "Well, based on your description, I wouldn't vote for that bill," she said. "It sounds burdensome and not justifiable to me."

There was just one problem. There is no such bill. There never has been; "602p" is not even a valid name for a congressional bill. The question was sent into moderator Marcia Kramer of WCBS News from a New York voter and Internet user, who obviously had picked up word of the bill from the Internet itself. It is just one of the many false, dopey rumors that spread quickly in cyberspace and live a vibrant virtual life completely resistant to three-dimensional reality.

The incident says just about everything about where we are as a Tech Nation. Politicians and journalists are no further along on this stuff than the average Internet user.

But rather than see this as disappointing or even scary, think of it as an opportunity, a time for informed citizens to organize into a movement that Stanford Law Professor Lawrence Lessig likens to a kind of "environmentalism for information policy." Just as Rachel Carson's Silent Spring kicked off the environmental movement in 1962, we are now at the beginning of a new journey in building public awareness for the digital age.

There are some real technology issues facing New York and the nation, for some of which the candidates offer positions that are not just off-the-cuff.

PRIVACY AND SECURITY

Amazon.com and other Internet companies have been changing their online agreements with their customers, in preparation for the sale of information they have gathered on them. These agreements are often written in cryptic legalese displayed in tiny type in a small box that prevents a customer from reading the whole document without scrolling down. Most consumers just click 'I Accept' without fully understanding the ramifications of what they are agreeing to. However, in an age when medical and financial information is increasingly stored online, consumers may be taking an unnecessary risk. According to a poll taken by the Internet Policy Institute, over three quarters of New Yorkers want federal laws to restrict what kinds of personal information can be collected online about them.

In June, Clinton addressed this issue at the New York State Broadcasters Association where she announced that she is a strong supporter of individual privacy rights, including the right to know if, how, when and how much personal information is being sold. Clinton pledged to give priority to medical and financial privacy, and protection against identity theft.

Lazio has said relatively little on the issue.

DIGITAL DIVIDE

Government officials, industry leaders, academics and non-profit groups alike worry that rapid changes in information technology, including the introduction of broadband or high-speed Internet access technology, will make the gulf deeper between those who have access to such technology and those who don't. This is commonly called the digital divide. New Yorkers are very concerned about the gap in Internet use between higher and lower income Americans; well over three quarters believe that the government should subsidize Internet access for underserved populations, according to the Internet Policy Institute poll. To this end, the New York City Economic Development Corporation aims to capitalize on the growth of Silicon Alley by promoting high-tech economic development with its Digital NYC initiative, a program that offers affordable, Internet-ready office space in new high-tech districts.

Clinton has shown support for initiatives that help to bridge the digital divide such as increasing spending on new technology for public libraries, increasing economic and educational opportunities for minorities through tax credits and government guaranteed loans to new businesses in economically depressed areas, and increasing specialized technology training programs for teachers. In April, Clinton attended the Women of Silicon Alley Summit where she introduced a new initiative to increase funding for women-owned businesses and teach women how to take their businesses online including the establishment of Women's Business Centers to provide support for these new businesses. Clinton has three proposals in this area that will finance and deploy technology in poor urban and rural areas and help small businesses upgrade their technology. Clinton also proposes increasing funding for wireless research and development for rural areas. She supports a variety of initiatives to increase the technology skills of New York's workforce including doubling federal funding for Regional Skills Alliances (RSAs), helping to foster school-business partnerships, making the Research and Experimentation Tax Credit permanent, and increasing the number of business incubators nationwide.

Lazio does not address the "digital divide" as such. Instead, his efforts in this area focus on technological economic development initiatives that will increase educational programs and employment opportunities. As congressman, Lazio supported the expansion of the term "computer professional" to include high income Internet professionals under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) so that companies are no longer required to pay overtime to these workers, thereby boosting the economy. He also introduced the Small Business Tax Fairness Act to increase the minimum wage and give tax breaks to small businesses. The Information Technology Industry Council gave Lazio a score of 100 percent for favoring policies that promote economic development and innovation. On the education front, Lazio helped secure funds for a youth computer-training program and for the Center for Emerging Technology at the engineering school of the State University at Stony Brook. He also pushed for U.S. Department of Commerce funding for a new technology incubator, established a high-technology "Working Group" for executives and served as a member of a roundtable of high-tech chief executive officers in Long Island.

E-GOVERNMENT

In the next few years, more and more government services will be available online. We will be able to pay our taxes, register for government programs and maybe even vote online. This year, Arizona became the first state to conduct electronic elections. Currently, the New York City Department of Information Technology is working on improving its e-government interactive services. Right now, New York is testing CityAccess, a kiosk that allow citizens to interact with city agencies and obtain information on job and housing opportunities, food and public assistance programs, adult and child services, health awareness bulletins, parking rules and regulations and senior citizen benefits and entitlements.

Neither candidate has addressed this issue publicly.

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND COPYRIGHTS

Is it legal to 'share' digital music and movies by copying files onto your computer, or are you violating copyright laws? Recently, the Napster case, in which the music industry is suing a now hugely popular site that was started by a teenager to share music with his friends, brought this issue into the public eye. Some have argued that programs like Napster actually increase music sales, and allow some artists to circulate their music to millions of new listeners. But the music industry, afraid of losing billions of dollars, is determined to enforce their copyrights. In general, American law is biased towards the protection of intellectual property and copyright laws, but denial of rights to circulate files could be also seen as an attack on free speech. Intellectual property issues are also important because technology companies compete with one another to patent as many of their inventions as possible. Conflict often arises between companies over the legitimacy of their patents and their resulting position in the market as a result of the patents that they hold.

Neither candidate has addressed this issue publicly.

E-COMMERCE

Similar to mail-order catalogues, on-line purchases have not been subject to taxation unless the seller has offices in the state where the buyer resides. However, many people feel that Internet businesses have an unfair advantage against main street businesses in part because they can offer goods tax-free. The government also has lost substantial income due to the rise of e-commerce. Over half of New Yorkers feel that they shouldn't have to pay sales tax for purchases they make over the Internet, according to the Internet Policy Institute poll.

Neither candidate has addressed this issue publicly. However, we might infer from their comments on the fictional bill 602p that they would both be opposed to taxation of the Internet.

Laura Forlano is a doctoral student studying communication technology policy at Columbia University.

NYC's New Budget and Kids

New York City's new budget, which went into effect July 1st, has real goodies for kids in it, for the first time in years. Some examples:

- $20 million to the Board of Education to put gym classes back into elementary schools for the first time in 25 years, when they were eliminated during the 1975 fiscal crisis.

- $25 million for construction of new day care centers

- $34 million to expand, by 15 percent, the Department of Health's Early Intervention program for at-risk infants.

"We started in the seventh circle of hell and six or seven years later we're in a city that has a completely different view of its obligation to children and families," says Gail Nayowith, executive director of the Citizens' Committee for Children, a group that lobbies City Hall on behalf of kids. "There's still a long way to go - it's not a perfect situation, but it's significantly better than it was for children and the people who care for them."

New York City children can thank the robust economy. A large percentage of the $2.9 billion surplus in city coffers comes from income taxes on Wall Street bonuses. Overall, the new City expense budget, which runs from July 1, 2000 to June 30, 2001, increases City spending by $1.3 billion, to over $26 billion, according to an analysis by the Independent Budget Office, a government agency that provides non-partisan information on the City budget to the public. And a sizable portion of the budget is going to children's programs. According to figures provided by the Independent Budget Office and the Citizens' Committee for Children, nearly 20% of the increase, or about $256 million of the City's money, is earmarked for programs that directly benefit children, including tens of millions for summer school, for extended-day programs at the City's lowest performing schools, for new health initiatives and for child welfare services. This tally omits major institutions that kids use extensively but not exclusively, such as the Department of Parks and Recreation, the libraries, and the Department of Cultural Affairs. Kids also come out ahead in the City's four-year capital plan. The plan calls for $24.9 billion in investments over Fiscal Years 2001 - 2004. A whopping 22% of this budget is devoted to school construction. Only a package of environmental protection projects claims a larger share of the capital budget. For all the good news, the budget still contains major disappointments for frontline child advocates. Mike Arsham, for one, wishes the City had done something to address the huge disparity at the Administration for Children's Services between the amount spent on removing children from their homes and the amount spent on services to make removals unnecessary. The City added only $4.4 million for preventive services to a $2 billion child welfare budget. Arsham, director of the Child Welfare Organizing project, says, "Time and time again what we're saying to families is we know what you need, but all we have to offer is foster care placements." And Nayowith was happier before the New York State legislature got its hands on the City budget in late June. The City Council and Mayor Rudolph Giuliani wanted to give low-income New Yorkers a $73 million package of earned income and child care tax credits, but the legislature, which has final say on such matters, rejected the plan. "That would have been the best case scenario," Nayowith says of the budget before the legislature killed the tax package. "You would have seen strategic investment, and then you would have seen, through the tax system, some very enterprising ways of helping families. We're now in the next best scenario, where the mayor and the City Council did a very god job of thinking about the best way to take care of kids."

Peggy J. Farber is freelance journalist specializing in children's issues. Her reporting on conditions of NYC children has appeared in City Limits Magazine as well as on National Public Radio.

A Trust Fund For America

From The Wall Street Journal, June 16, 2005

By FELIX ROHATYN

June 16, 2005; Page A16

Thomas Jefferson committed the U.S. to acquire the Louisiana Territory from France for $15 million. In so doing he doubled the size of the U.S., guaranteed navigation on the Mississippi, and opened the American West. But Jefferson, Madison, and Congress were understandably worried about the size of the commitment. After all, total revenues from import duties then were only $12,280,000. Nevertheless, Congress approved the purchase and the greatest investment in American history was completed when a British bank and a Dutch one underwrote the bonds required to pay Napoleon on schedule. In doing so, they were confirming America's creditworthiness and recognizing the huge present and future value of the assets acquired by America.

Under today's budget rules, the Louisiana Purchase would have been regarded as a budget-buster and the Congress might well have turned it down. As a result, Jefferson might have had to go to war with France to accomplish the same purpose, an alternative that was under consideration at the time. This may be an extreme example, but it illustrates a much-overlooked reality -- borrowing for investments is different from borrowing for recurring expenditure and should be treated as such. This fundamental reality is sadly missing in the current debate about deficits and economic policy.

The partisan crossfire over deficits has two poles -- the one marked out by Vice President Dick Cheney's remark that "deficits don't matter" -- and the position associated with former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin, that current deficits are unsustainable and that drastic spending and tax changes are urgently required. Both sides are likely to remain firmly entrenched in their respective positions, despite the risk of a dollar crisis if current policies are continued over the next few years. However, regardless of which side of this debate you subscribe to, an even more fundamental crisis could grip our economy if we turn away from the investments that determine our future standard of living. We risk balancing the budget but leaving our long-term growth needs unmet.

Public investment has, by tradition, meant infrastructure: Roads, trains and bridges, public transportation, schools, etc., have provided the private sector with the complementary investments that improve business productivity and improve our standard of living. Largely the product of a federal-state-local partnership, it has been badly neglected over the years. A biannual "balance sheet" provided by the American Society of Civil Engineers, grading the categories of infrastructure from schools to sewers, indicates a need for $1.6 trillion over 5 years to bring national infrastructure up to reasonable standards; that need increases by $300 billion every two years.

In addition to traditional physical capital, an even more important component of our infrastructure is our intellectual infrastructure. In the last two years, Arnold Schwarzenegger has asked his legislature for $3 billion to finance stem-cell research and Jennifer Granholm has asked hers for authority to sell $2 billion of Michigan state bonds to finance research aimed at improving the competitiveness of its auto industry. By doing so, Govs. Schwarzenegger and Granholm are doing what the private sector does daily -- financing R&D. Corporate America does this mostly by equity; the governors, lacking the ability to issue stock, propose to do this with state debt. That is entirely appropriate. We cannot compete with China by making cheaper T-shirts or forcing them to revalue the yuan by 10%. We can only do so by fighting tooth and nail for supremacy in education, intellectual capital and R&D, and both the federal government and the States must play a role in that fight.

In 1865, when Lincoln created a system of land grant colleges (which ultimately totaled 213), he initially provided America with 75% of its engineers; when FDR proposed the GI Bill, he allowed millions of young Americans who would not have had a college degree to become the source of our technical and industrial power. Through the years, the Bill has provided $70 billion in aid to veterans. Can anyone doubt that the investment has been returned manyfold? Eisenhower continued the tradition of federal involvement in infrastructure with the Federal Aid Highway Act, which generated millions of jobs and created a suburban economy now basic to the U.S., with enormous incremental value.

Not much of this found its way onto a federal balance sheet. The budget does not recognize assets; it only recognizes expenditures and liabilities. The Louisiana Purchase would have been reflected by the debt issued to Napoleon and have resulted in a large deficit. Land grant colleges and the education of GIs were treated as simple expenses. It is bad enough to try to deal with large and growing deficits created by ongoing expenditures, but the process will produce even worse choices if important, albeit intangible, assets are carried as liabilities.

A federal capital budget would help correct this problem, but would be so fraught with political difficulties that it is not worth the attempt. Yet there is a recent development which suggests a remedy: the return of the 30-year Treasury bond. Long-term bonds should finance capital assets and their issuance should be dedicated to that purpose. Even longer maturities than 30 years can be envisaged; corporations and governments have issued up to 50-year bonds.

To help deal with our shortage of public capital investment, the Congress should authorize a trust fund of up to $100 billion, to be financed over a five-year period by special 50-year Treasury bonds created for that specific purpose. The fund should be used to co-finance high priority state and local investment programs, including physical infrastructure and projects to create intellectual property. Tight outside controls will be applied to the operations of the fund, and it should also be subject to the federal debt limit.

In addition to cutbacks on infrastructure, globalization puts pressure on domestic employment. This impacts heavily on certain industries like the auto industry, and on the states where they are concentrated. An infrastructure trust fund could be helpful in making investments on a regional basis where appropriate. Creating such a fund would also allow us to redesign programs that deliver these investments, balancing new construction with more effective life-cycle management. A special commission under the aegis of the Center for Strategic and International Studies is rethinking program delivery and should provide new directions soon. In the meantime it is counterproductive to starve long-term investment because of presently excessive recurring spending; over the long run it only makes our economic challenges worse by slowing the creation of national wealth.

Jefferson, Lincoln, FDR and Eisenhower proved that public investment could generate vast returns. The federal budget should be a tool to encourage national investment instead of writing it off. Let us adopt a different perspective of our national wealth and how to increase it.

Mr. Rohatyn is chairman of the CSIS Commission on Public Infrastructure.

Â

A Bloomberg-Era Reform Worth Saving?

In the waning days of the Bloomberg administration, when many of the mayor’s controversial education ideas are once again under attack, one chief target of critics has been the school network structure, which broke up the geographically organized school districts and allowed principals to self-select into one of about 60 support organizations.

These days, just about everyone from the principals’ union (the Council of Supervisors and Administrators) to Merryl Tisch, Chancellor of the NY State Board of Regents, to Mayor-elect Bill de Blasio are targeting the networks for elimination. Tisch recently charged that the networks have “basically failed children” who are English Language Learners and have special needs. Last January, de Blasio said: “I am dubious about whether this current network structure can be kept.”

But now, a group of 120 principals has issued a plea, in the form of a letter, in support of the network structure. The letter, which is reproduced below, was sent to Mayor-elect de Blasio, the UFT, the CSA, Schools Chancellor Dennis Walcott and Shael Polakow-Suransky, the Senior Deputy Chancellor last Friday.

It says the networks offer the following supports, which were not “necessarily” provided through other more traditional structures at the Department of Education:

1. The gathering of schools of similar visions or purpose: the internationals, special ed reform focused, collaboratively structured, and schools committed to alternative assessment. This enables these schools to work more closely together and support each other towards better meeting their missions.

2. Shifting the supervisory structure into an advisory and support structure. It makes all the difference in the world that the network leader and team members are not the principals’ rating officer. Our networks have been responsive to us and in many cases network principals have had a say in the selection of network staff.

3. Networks support professional development that better meets the needs of the teachers, administrators, and other support staff in our schools and that allows for cross-pollination across our schools.

4. Because of racial and economic segregation by neighborhood in New York City, geographic districts are often segregated as well. Self-selected networks offer the option of racially and economically diverse schools working together and benefitting greatly from this collaboration.

The networks go to the heart of what might be the most important education initiative of the Bloomberg years: An effort to turn principals into educational leaders by giving them both greater autonomy and support in exchange for increased accountability. Under the network structure, principals were no longer just accountable to superintendents. The networks represented a countervailing power designed to support principals—and, through them, the needs of students in each individual school—by providing information and advice on everything from budgets to professional development. Principals could—and did—vote with their feet if they were unsatisfied with the services they got from their networks.

A Signature Bloomberg-Era Education Innovation Is At A Crossroads

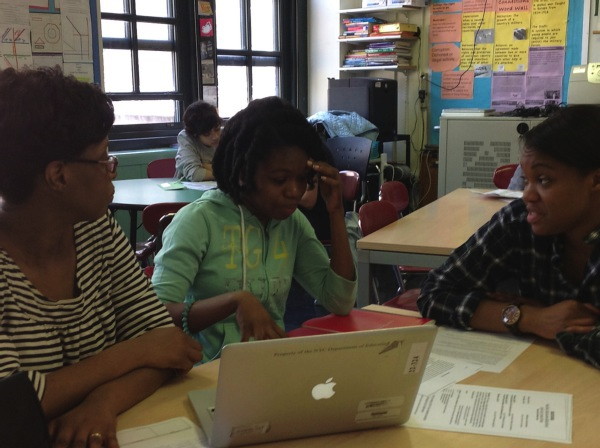

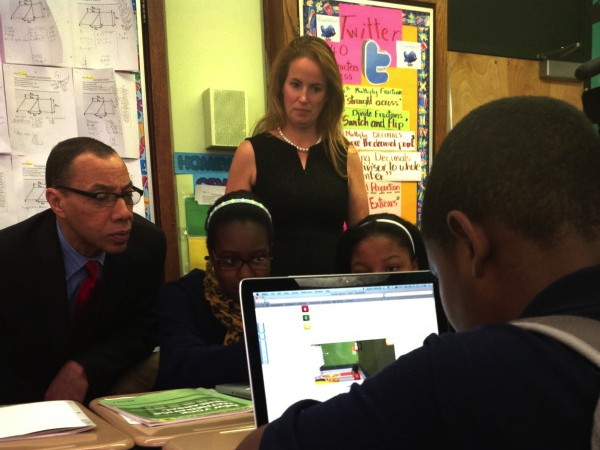

NEW YORK — One morning in March, New York City Schools Chancellor Dennis Walcott stopped by Global Technology Preparatory, a middle school in East Harlem.

He watched as sixth–graders who had just read Yummy, an acclaimed graphic novel based on the real-life shooting of an 11-year-old Chicago gang member, searched for articles on their laptops to support an essay on whether child perpetrators should be tried as adults.

In another class, a student recited a poem that built on what she had learned in an extended-day apprenticeship.

Walcott also chatted with Valerie Miller, a teacher who has spent years working with foreign-language software that allows kids to study a range of languages.

Global Tech, a school where most kids are poor, black or Latino — and about 40 percent have special-needs certifications — has become a showcase for one of the Bloomberg administration’s signature education initiatives: the so-called innovation zone or iZone.

The premise behind the iZone initiative is that digital technology, projects based on real-world problems and tailored to student interests, as well as new approaches to scheduling both the school day and teachers’ time, will both expand the horizons of the traditional classroom and inspire kids to learn.

The iZone initiative aims to address the disconnect between students’ wired lives and the traditional chalk-and-blackboard classroom that, according to some education-technology experts, makes kids today less receptive to education.

In the waning months of the Bloomberg administration, however, the iZone initiative, and schools like Global Tech — which have benefited from extra funding and support offered through the program — are being buffeted by a series of changes, from budget cuts to city-wide implementation of the Common Core state standards.

And, with a new mayor set to take office in 2014, and likely changes in leadership at the Department of Education, it is unclear whether this Bloomberg legacy will endure.

Some of the changes, such as a new venture-capital-like challenge meant to get schools to compete for what is likely to be a much smaller pot of funding, are just the latest examples of the tumult that has characterized the experiment from the beginning.

As one iZone veteran told the Gotham Gazette on the condition of anonymity, ticking off the four executives who have run the organization in as many years: “The iZone is like the Hudson; it’s constantly flowing, always changing.”

The iZone highlights both the promise and the hype of the kind of outside-the-box thinking that was a hallmark of the Bloomberg years. It also demonstrates how challenging it can be to disseminate even the best ideas within New York City’s large and ever changing public school system.

The iZone began in the 2009/2010 school year with 10 pilot schools. A few of the schools, including Global Tech, showed great promise both in terms of traditional measures — Global Tech received an A and B on its first two graded school report cards, as well as off-the-charts marks for student engagement, academic expectations and attendance. But the majority of the pilot schools dropped out of the experiment.

With those “failures,” the DOE wrote the pilot year out of its history books and began dating the launch of the iZone to the following 2010/2011 school year when it expanded to 81 schools. The iZone initiative today encompasses 250 of the city’s 1,700 public schools.

“It’s been an iterative journey,” says Andrea Coleman, who became CEO of the education department’s Office of Innovation, which runs the iZone, in August. “The personalized learning experience overall has been a huge success for the district.”

Last year, the iZone became a two-tier system with about 200 schools taking part in a limited way via access to education software offerings on the Department of Education’s iLearn portal for interactive learning. Another 50 schools, including Global Tech, are involved with more extensive experiments, such as those involving scheduling, as part of what has become known as iZone360; participating schools also have access to a broader range of supports, including outside consultants.

For New York City’s one million kids, such innovations have the potential to put an end to what Ken Robinson, the British education expert, calls the batch-processing approach to education, in which kids are sorted by their “manufacturing dates,” i.e. by age and not ability or interests.

DEEP IN THE iZONE

The iZone has worked best where it has hewed to the vision of personalized learning.

At Global Tech, Carolyn Tarr, a music teacher, uses everything from garage-band software to podcast performances to mini-lessons on rhyme and rhythm, to teach a “challenge-based performance class.”

The two sections of Tarr’s class, which each meet once per week and have about 18 students each, work in small-groups — some formed bands, while others worked solo on slam poetry — in one cacophonous classroom.

For Walcott’s visit, Zoe Cambrelen, an eighth grader who was first inspired to write poetry during a poetry apprenticeship that was part of Global Tech’s after-school program, read, “Fight Like a Girl,” which reads in part:

When they look her up and down and tell her not to hang around, she says, this is my city …

When they come around and try to beat her down, she goes the distance.

And you know why? Because she doesn’t cry. She fights like a girl.

Meanwhile, on the Upper West Side, the West Side Collaborative, a respected, long-established Title 1 school, used its participation in iZone360 to expand experiments in flexible staffing, block scheduling and digital technology — all key iZone initiatives — that it had begun a decade earlier.

This year, for the first time, West Side created so-called “personal learning modules” tailored to the literacy needs of each student.

Working with a team of faculty, Jeanne Rotunda, the school principal, scheduled the entire seventh and eighth grades for a combined literacy period on Mondays and Fridays to work in small groups on discreet skills , which are based on each student’s abilities and are mapped to the common core standards, as well as their preferred learning style and interests. The regular curriculum continues to be taught Tuesday through Thursday.

To help decide which PLM would be most beneficial for each student, and “to establish a baseline for student's mastery of a particular set of Common Core Standards,” West Side teachers developed interactive challenge-based assessments. One of these, the Pacific Trash Vortex, which is based on a Texas-sized mass of garbage in the North Pacific, assembles a series of documents that students need to study, including news stories, lab reports and maps of ocean currents.

Each student is asked to imagine that she is an ecologist/oceanographer who has been hired by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to propose solutions to the United Nations. Students have to explain both the problem and the consequences of the vortex if it isn’t solved, and create a Google presentation on their findings.

“The assessment is rigorous, engaging and authentic, and includes some gaming principles,” said Paul Kehoe, a 32-year-old teacher who helped develop the assessment.

Teachers also surveyed the kids about their interests: sports, say, or art; their preferred learning styles — working in groups, individually or with a teacher; as well as data from their assessments.

By freeing up nine teachers to work with 120-or-so students in the combined grades, the teacher-student ratio for the PLM groups is much lower than it would be in a typical public- school classroom: While the largest group has 25 kids, the rest range in size from nine-to-18.

To support the idea of student-focused learning, West Side has also developed a highly nuanced “outcomes-based” grading system, in which students receive a grade of 1, below grade level, to 5, above grade level, on myriad competencies. Part of the point is to get kids to better understand their strengths and where they need to improve.

During a recent afternoon, students shared their report cards with their parents in student-led conferences.

Natalio Gonzalez, an 8th grader who loves art (especially the work of Brooklyn-born graffiti artist-turned-painter Jean-Michel Basquiat) and was recently accepted at the esteemed LaGaurdia High School, pulled up a multi-page spreadsheet on his MacBook to show his progress.

“My weakest spot is in communication,” explained Natalio, who earned many 4s on his report card, but noted that he got a 3 in communication. He said students set academic goals with their advisors during a once-a-week “base-camp.” One recent goal for Natalio was to do a better job of discerning evidence and using it to make claims in written essays.

Nearby, Niomi Manigault, a seventh grader, was showing her online report to her mom and older sister, explaining she wants to improve her performance in social studies in which she got an 88 on her most recent assessment. She also said she needs help in math.

Judith Manigault, Niomi’s mom, says she is comfortable with the student-led conferences, which have only been in place since last January. “It holds her accountable,” Manigault said. “I'm able to reach out to teachers via email or schedule a phone call” with questions and concerns.

Both West Side Collaborative and Global Tech are one-to-one laptop schools —though West Side’s computer program predates the iZone. What the iZone has brought is both resources — including consultants who are expert at scheduling and technology — and, equally important, says Rotunda: “permission to push further.”

Importantly, both schools also have developed their iZone innovations in collaboration with, and in order to maximize, the expertise of teachers. That is not always the case — either in the iZone or among education policymakers.

EVALUATING THE iZONE INITIATIVE

The iZone came of age in a climate where education technology has often been used as a Trojan horse for sidelining teachers unions and increasing class size. Conservative activists, led by Terry Moe and John Chubb (Liberating Learning: Technology, Politics, and the Future of American Education), promoted an explicitly anti-union, anti-teacher agenda in which kids would learn via computer with only occasional assistance from “asynchronous” instructors who work out of centralized teacher warehouses.

Joel Klein, the former schools chancellor who now runs Amplify, News Corp.’s education-technology business, had great enthusiasm for the iZone, especially its technology component: He envisioned classes in which Nobel laureates, such as Richard Feynman, would teach large groups of students via video.

“Joel misses the essence of teacher-student interactions, and the extent to which teachers focus on students’ physical and emotional well-being, in addition to their academic learning,” said Eric Nadelstern, the former New York City deputy schools chancellor and visiting professor of practice at Columbia University’s Teachers College. “Virtual communities don't raise children, people do.”

A subsidiary of Amplify has three current contracts with the DOE, though none for the company's new tablets.

There has been little systematic research inside or outside the iZone on the efficacy of K-12 online education. The number of U.S. students enrolled in online courses surged 47 percent in 2008 to just over one million, up from 700,000 two years earlier, according to two studies conducted by Anthony G. Picciano and Jeff Seaman, in a project funded by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. However, in the 2008 study, K-12 Online Learning, the authors note that, as of 2007, “no organization-public or private was systematically collecting” data on K-12 online schools.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that technology, in the absence of close teacher-student connections, doesn’t improve outcomes, especially in inner-city schools where most kids can’t count on parents to help them with their work.

Take the iZone’s School of One, which was hailed by Time as one of the 50 best inventions of 2009. School of One uses a computer algorithm to sort kids by ability, generate a daily “playlist” of assignments for each child and grade quizzes. About eight adults supervise a typical jumbo-sized School-of-One classroom where most of the 150 kids work on computers, while a few teachers help smaller groups of students; but since half the adults are student teachers, the actual ratio of certified teachers to students is about 36-to-1. Many see School of One as part of a trend to create “teacher-proof” education.

After the first full year, School of One saw decidedly mixed results. Two of three pilot schools dropped the program and the founder of School of One, Joel Rose, left the DOE. While the School of One continues to operate in a few schools, there is little talk these days about the program’s “miracles.”

THE PRECARIOUS FUTURE OF THE iZONE

As the iZone enters its fifth school year, it faces both strategic and financial challenges.

The iZone’s budget, which includes both public funds and private grants from philanthropies, such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, was $47 million in the 2012/13 school year. The city learned in December that it had lost a $40 million bid for Race-to-the-Top funding, which was aimed at rewarding schools that promote “personalized learning,” including those in the iZone.

A map of iZone locations (source: NYC OpenData)

New York City also has yet to receive $256 million in Race-to-the-Top grants, which have been withheld by the State until a teacher-evaluation process is in place. In addition, the city lost about $257 million in the 2012/2013 school year for failing to arrive at an agreement with the United Federation of Teachers on a new teacher evaluation system — although a court recently ruled that the state could not withhold the funds to punish the schools.

Meanwhile, the DOE’s $8.282 billion budget allocation from the state for the 2013/2014 school year represents about an 8 percent increase over the 2011/2012 school year.

Some schools — in and outside the iZone — also will benefit from a Microsoft class-action settlement with New York State, which will provide $87 million in the form of technology vouchers that will be reserved for high-poverty schools defined as those where at least 50 percent of the students are enrolled in a free or reduced-price lunch program.

At the same time, iZone schools are girding for a new system of “challenge” grants, which will be “shorter, sharper and more dynamic” than the more open-ended funding that has been provided thus far. The first of about 10 annual challenges will take place in May.

The challenge-grant process reflects the influence of business ideas on the DOE, which has worked with companies like Cisco and Apple since the beginning of the iZone.

For example, challenge-grant recipients are required to use such business-inspired strategies as “hackathons” — in the high-tech world, these are typically intensive one-day to one-week product development jam sessions. One long-time iZone consultant lauded the competitive nature of the challenge grants, saying they would ensure that only the best ideas, and most committed schools, get funding.

But educators are concerned. “School innovation isn’t like software design,” said Nick Siewert, a senior educational consultant at Teaching Matters, a leading nonprofit professional development organization, who works with several iZone schools.

Siewart argues that school improvement isn’t analogous to one-time solutions or product fixes; rather, he says, it’s about iterative learning and follow-through.

Chrystina Russell, the principal of Global Tech, worries that the challenge grant process will pit schools against each other and favor projects that “have immediate returns.”

She is also concerned that established schools, already working on a portfolio of innovations, will get short shrift; she notes that Global Tech has not gotten any new funding yet for technology for the 2013/2014 school year—the first time she has gone into a new school year without such a commitment—and worries that the iZone will stop supporting ongoing experiments in favor of quick fixes.

Nor has the DOE done a good job of disseminating lessons learned in the iZone.

There is relatively little systematic research on the myriad innovations across the iZone, and few mechanisms for sharing the ideas that work, as well as those that don’t.

“We know schools are idiosyncratic places, and finding the right opportunities to scale and diffuse ideas has always been a challenge,” iZone’s Coleman said.

She added that one of the iZone’s goals is to focus on “scale and diffusion” and finding better ways “to maximize ideas across the system.”

One way the iZone is hoping to do that is by expanding a system of principal and teacher-led affinity groups and events in which schools share the know-how they have developed in such areas as outcomes-based grading or fostering greater social-and-emotional awareness among kids.

Also this year, for the first time, schools receive some funding for assisting other schools.

This year, West Side Collaborative is helping East Bronx Academy implement student-led conferences. However, West Side’s Rotunda notes there are limitations on the extent to which schools can learn directly from one another: “People learn through creating — by seeing something in one version and trying to create it for your own world.”

Nor is it clear whether the education department will continue to fund this school-to-school mentoring initiative in the next school year.

Then, too, there is the chicken-and-egg problem.

The most respected iZone schools are ones that are noted for strong leaders who took advantage of myriad education department initiatives, especially the push to grant principals more autonomy and flexibility in exchange for greater accountability.

Even now, some of New York’s most intriguing grassroots efforts aren’t officially part of the iZone at all, but are led by entrepreneurial principals and teachers.

For example, the Staten Island School of Civic Leadership, a new school on Staten Island, uses software programs on the iZone’s iLearn platform to help its most advanced eighth graders take the regents exam in algebra.

But a promising experiment at the school is taking place one grade below, and entirely outside the iZone framework, in a seventh-grade class led by three teachers under what school principal Rose Kerr calls the “triad” system.

She says the model is based on close collaboration among the teachers, block scheduling, intensive multi-disciplinary class projects and digital literacy.

For example, the class recently finished a Declaration of Independence for Staten Island, which began with a unit on the history of American War of Independence, including discussions about taxation without representation. It went on to cover questions about democracy versus autocracy that drew, in part, on readings from MacBeth. And it culminated with the writing of a press release that explains the secession movement and tweeting the plan.

The school received Teaching Matters’ Elizabeth Rohatyn Prize, which recognizes principals who create rigorous and innovative learning environments, for its triad system. (West Side’s Rotunda won the first prize in 2011.)

EDUCATION INNOVATION BEYOND BLOOMBERG

The Bloomberg years, with their school closings and the battles over punitive teacher evaluations, have often been confrontational and divisive. Yet, the best of New York’s iZone schools have flourished on a culture of collaboration and entrepreneurialism fostered by strong principals and creative teachers who took advantage of a climate that promoted autonomy and accountability.

Now that autonomy is eroding, with a wave of new mandates from Tweed, even as the Common Core assessments and mayoral elections bring more upheaval. Last week, the iZone was abuzz with the news that two respected iZone principals had not received tenure.

Where the Common Core assessments are concerned, which have unsettled schools both inside and outside the iZone, the iZone schools have at least one advantage: Next year the assessments are to be administered online, which might help maintain funding for technology. It will also give schools that have done the upfront work on infrastructure an edge.

The real test for the DOE in the post-Bloomberg era will be whether it can nurture the entrepreneurism of both teachers and principals that have flourished at the best iZone schools, and find a way to spread that culture and the lessons learned throughout the system.

Andrea Gabor is the Bloomberg Chair of Business Journalism at Baruch College/CUNY; she is working on a new book on education reform.

___

Correction: This is an updated version of the story. A previous version incorrectly identified Richard Feynman as a chemist. He is a physicist. The story also misidentified him by the wrong first name.

Will A “Bar” Exam for Teachers Improve Student Performance?

NEW YORK — A growing nationwide push for more rigorous teacher-licensing standards sweeping state houses from New York to Washington has reformers on sometimes opposing political sides looking at what was once considered nearly unthinkable: a bar-like exam for educators.

Even the American Federation of Teachers, the powerful union, has taken the old adage that the best defense is a good offense and begun to campaign for such exams as teachers are increasingly blamed for low student achievement. The AFT has also been campaigning for higher standards both for prospective teachers and for teacher-preparation programs.

In so doing, the AFT has found common cause with a number of education reformers with whom it normally doesn’t agree. A new AFT report, “Raising the Bar: Aligning and Elevating Teacher Preparation and the Teaching Profession” has won praise from many quarters, including Arne Duncan. And Joel Klein, the former New York City Schools Chancellor who now heads News Corp.’s education business, floated a similar proposal last November.

New York is among the states moving toward tougher requirements for entry into teacher-preparation programs — currently, New York has no such minimum requirements — as well as a bar-like exam for graduates. After a panel that he created said it concurred with the AFT’s report recommending a bar-like exam, Gov. Andrew Cuomo, endorsed the idea in his State of the State address on Wednesday, saying that “every teacher” should take such a test and pass it “before we put them in a classroom.”

The New NY Education Reform Commission, convened by Cuomo in April 2012, recommended in a preliminary report that prospective teachers have a minimum 3.0 GPA, as well as an assessment, such as the GRE for graduate programs, or the SAT/ACT for undergraduate programs, but, notably, doesn’t specify a minimum score that candidates must achieve. The report, which points out that the state’s current certification exam has a 99 percent pass rate, also calls for adopting a ‘bar'-like exam that will test new teachers on how well they are prepared to lead classroom instruction.

Randi Weingarten, the president of the AFT and a member of Cuomo’s education commission, said the world’s most lauded education programs in countries like Singapore and Finland also have teacher-education programs with high degrees of quality control.

“Preparation really matters,” she says. “We talk a good game in this country about the importance of teachers, but no place in this chain do we actually treat it as important.”

The AFT report is largely a critique of the nation’s teacher-education system — a hodge-podge of traditional university based education programs, alternative certifications, and online programs — that the report says is “at best confusing and at worst a fragmented and bureaucratic tangle.” The AFT says it wants to develop national consensus on a “mechanism for ensuring high standards,” in large part by improving the connection between teacher-preparation programs and on-the-ground teaching.

The bar-exam proposal coincides with two competing trends in K-12 education: on the one hand, the proliferation of alternative certifications that aim to attract young people from elite schools and are generally much shorter — and, critics say, more superficial — than many university based programs; and, on the other hand, a growing call for educational rigor in both teacher preparation and licensure requirements.

The proposal also follows a devastating 2006 critique, Educating School Teachers by Arthur Levine, the former president of Columbia University’s Teachers College, which took aim at both alternative certifications for doing away with “quality ceilings and floors” and the majority of traditional university based programs, which are “characterized by curricular confusion, a faculty disconnected from practice, low admission and graduation standards … and weak quality control enforcement.”

At the same time, an influential 2007 McKinsey & Co. report, which claimed that the nation recruits many of its teachers from the bottom third of college graduating classes, unsettled education policy experts, even though the claim is based on somewhat misleading data.

By proposing a bar-like exam, the AFT believes that it will force changes throughout the teacher-preparation pipeline, much the way the Flexner Report did for medical schools a century ago. The Flexner Report prompted states to write more rigorous licensing tests even as medical schools revamped their training programs and toughened entry requirements. One upshot was that by 1935, half the medical schools in operation at the turn-of-the-20th century had closed (and inroads made by women were reversed as most medical schools became all-male institutions.)

The AFT may also be gambling that more rigorous licensing standards will serve as a stumbling block for alternative certification programs, such as Teach for America, a key source of teachers for nonunion charter schools. While Abraham Lincoln famously qualified for the bar without going to law school, over the years, the increased rigor of the bar has made three years of law school a virtual requirement for aspiring lawyers.

The idea is also part of a growing push to reverse a trend — often the result of past and current political battles — that many educators say has dumbed down state and local licensing requirements. For example, in New York City, in the 1990s, the controversial Board of Examiners, which was initially established in the late 19th century to ensure that teaching jobs were based on merit, and not patronage, was eliminated in the aftermath of a lawsuit charging that the tests made it difficult for minorities to pass.

Today “it’s the right-wing reformers who are lowering standards,” says Diane Ravitch, a former assistant secretary of education and leading critic of the corporate education-reform movement, noting that Tony Bennett’s final act after losing his re-election bid, last November, as Indiana superintendent of public instruction — he was recently appointed education commissioner in Florida — was to weaken the state’s requirements for new teachers.

In particular, Bennett pushed through the state’s so-called adjunct teacher permit, which allows an applicant with just a BA degree and a 3.0 GPA, and who can pass a subject test, to teach for five years without any other training or student-teaching experience.

Bennett has defended the changes as expanding opportunities for teaching in Indiana’s classrooms. “The more opportunities we have with the ability to bring talent into Indiana classrooms, talent into Indiana school buildings, talent into Indiana school corporations, I think that’s good public policy,” he told reporters, according to Indiana’s State Impact news website.

Meanwhile, licensing rules in most states do little more than “screen out the bottom few who can’t master the English language or are badly schooled,” says Eric Nadelstern, the former New York City deputy schools chancellor and visiting professor of practice at Columbia University’s Teachers College.

The state that has pushed hardest to boost teacher requirements may be Massachusetts. After the Commonwealth created its much-lauded curriculum framework in the 1990s, it also revamped the state’s licensing regulations and tests. The new curriculum “would have amounted to little more than black and white noise without an academically stronger corps of teachers to teach to them,” writes Sandra Stotsky, who holds the “21st century chair in teacher quality” at the University of Arkansas and served as senior associate commissioner at the Massachusetts Department of Education, with responsibility for revising the state's teacher licensing regulations and tests.

Since 2005, Massachusetts has ranked at the top of National Assessment of Educational Progress scores in fourth and eighth grade reading and math, as well the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study scores in science and math in 2007 and 2011 (the state participated as an independent country).

Tougher tests will almost certainly result in many more failures among test takers. When Massachusetts instituted new licensing rules requiring prospective teachers to pass a new elementary math test, 75 percent of applicants failed in 2009, the first year the test was administered, according to Stotsky.

Many educators worry that the unintended consequences of a teacher’s “bar exam” could be to weed out many of the people they want in the classroom. “The only thing I'm certain a bar exam will do is keep out minorities,”says Chrystina Russell, the principal of a highly rated public middle school in Harlem who strives to make sure that her teaching staff resembles her black and Latino student body. Adds Nadelstern: “I don’t trust the testing industry to put together a test that is inclusive on the basis of gender, sexual persuasion or race.”

One reason that they see such an exam as disadvantaging people of color is that native speakers of Spanish and vernacular African-American dialects are at a disadvantage on written tests based on standard English because they often come from communities that are much more homogonous both ethnically and linguistically than those in which other immigrant groups live, according to Nadelstern, who adds: Speaking Yiddish didn’t get you very far if you grew up in an Irish, Italian and Jewish neighborhood.

The AFT counters that it has modeled its proposal on the so-called edTPA, formerly the Teacher Performance Assessment, which, instead of the prevailing multiple-choice tests and written essays, emphasizes a detailed “review of a teacher candidate's authentic teaching materials,” including video clips of instruction, lesson plans, student work samples and analyses of student learning. The aim of edTPA tests, which are subject-specific, is to evaluate how a prospective teacher actually teaches a given subject to real students, rather than her theoretical knowledge of teaching.

So far seven states, including Illinois, Washington and Minnesota, have adopted the edTPA, which was developed by Stanford University and the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education; test administration and scoring are being coordinated by Pearson, the education company. New York State is adopting edTPA beginning in 2014.

The edTPA assessment is not without controversy. Last year, students at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, one of 200 colleges in close to two dozen states where the new assessments were being piloted, refused to participate, saying the requirement that students submit 20-minute videos of their teaching practice was too onerous. They also questioned whether the test evaluators, who are being paid $75 to review each assessment, will put in the two to two-and-a-half hours necessary to do a thorough job. While Pearson helps to recruit scorers, Stanford notes that the scorers are experienced teachers who have been specially trained to evaluate the assessments.

Taking the edTPA will cost prospective teachers $300, about double what licensure tests cost today, but still far less than other licensing tests, such as those for nursing or the law.

Such controversy may be why the AFT, rather than adopting the edTPA outright, has asked The National Board for Professional Teaching Standards, which established the standards for so-called master teachers, to convene a gathering of educators and other “stakeholders” to design a multi-dimensional entry bar that could well include edTPA, minimum GPAs for teacher-prep candidates, as well as new student-teaching requirements.

With many states already signed up for edTPA, there is a danger that the AFT’s “bar exam” could result in yet another addition to the national licensure smorgasbord — rather than a national consensus.

“There is a tension here with the AFT’s desire to get to a single national system,” concedes Linda Darling-Hammond, the Charles E. Ducommun Professor of Education at Stanford Univ., and a contributor to edTPA’s development. “How to get there is not immediately clear. We already have a patchwork. It’s conceivable that you could end up with more than one addition to the current schema.”

The biggest problem with the AFT’s proposal may not be getting consensus — but getting it too quickly. The rush to jump on the next big thing, no matter how dubious the evidence, may be the biggest Achilles heel of the education reform movement. EdTPA’s predecessor, a performance-assessment test known as PACT that has been used in California for several years, has shown promise. Yet it will be a few years — when student achievement data are available for the teachers who participated in the edTPA pilots — before strong conclusions can be drawn on whether the assessments can weed out bad apples and select for teachers who consistently improve student achievement.

But that hasn’t stopped numerous states from jumping on the edTPA bandwagon. Similarly, even though the Massachusetts curriculum framework propelled student achievement in the Commonwealth to the top of national and international rankings, the state effectively jettisoned that framework for the untested Common Core; Massachusetts has also embraced edTPA.

As for whether a “bar” exam will help get teachers, and the teaching profession, more respect: That might be an even bigger hurdle.

____

Andrea Gabor is the Bloomberg Professor of Business Journalism at Baruch College/CUNY and the author of several books, including The Capitalist Philosophers

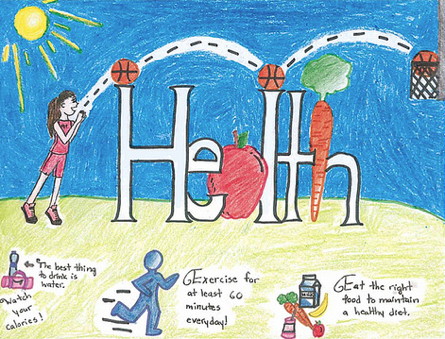

Council wants to know whether kids are getting enough physical ed

A winning design from the DOE's 2012 school wellness poster contest.

NEW YORK — A group of City Council members is trying to change the conversation about the obesity epidemic from soda to the lack of physical education in public schools.

In a letter sent earlier today to Schools Chancellor Dennis Walcott, the group of 34 led by Melissa Mark-Viverito and Letitia James, called for increased physical activity in the public schools, citing reports that they are not meeting state standards.

They also requested information on how much time children spend in physical education classes.

"With all of the public discussion about the mayor’s proposed ban on the sale of large sugar-sweetened beverages, we cannot neglect the critical role that physical activity plays in reducing obesity," they said in a statement.

The city's Department of Education responded by saying it had created an office dedicated to overseeing physical education, health education and wellness in 2003.

“We are helping schools provide a high-quality physical education, and through the obesity task force, we will be expanding fitness and wellness programs," said Deidrea Miller, a DOE spokeswoman.

The obesity task force was convened in January, with commissioners from major agencies, to find innovative policies to reduce the rates of New Yorkers who were obese or overweight. Among the proposals, the DOE said it would increase funding for health intiatives; create "wellness coordinators" to advise schools; and work to develop the connection between health and nutrition in cafeterias.

The proposed ban on the sale of sugary drinks in containers larger than 16 ounces at any food establishment that receives a health department inspection also came out of discussions by the task force.

The proposal has won praise from public health experts, and ridicule from comedians.

The Bloomberg-appointed Board of Health will vote on whether to pass the new soda regulation in September.

See the letter below:

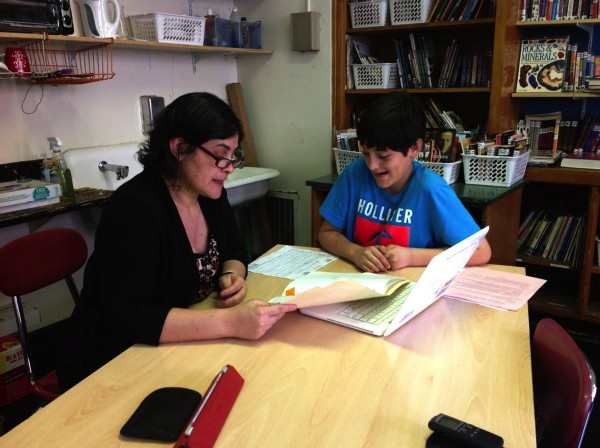

When Making a Great Teacher is a Team Effort

Photo by Andrea Gabor

Just a few years ago, while teaching at a middle school in the Bronx, David Baiz was given an unsatisfactory rating and targeted for elimination.

So when New York City published its Teacher Data Reports last week, Baiz, who now teaches at a middle school in Harlem, had reason to be, at the very least, relieved. He was ranked in the 91st percentile, or above average.

But Baiz, 29, knows that neither rating was accurate or useful. The TDRs violate basic rules of statistics because they assume that students are assigned to class rooms on a random basis, which is not the case. They also are riddled with data errors: In the case of Baiz’s ratings—he has received two TDRs in his teaching career—while both pegged him as “above average”, they both included likely errors in the value-added portion of his rating, the wrong number of students in his classes and a high likelihood that some of the students included in his assessment may never have been in his class.

Baiz’s unsatisfactory evaluation, on the other hand, captured his inexperience as a first-year teacher, as well as the effects of a family crisis that impaired his performance; however, the rating did nothing to assess—or foster-- his considerable potential.

Evolution

These days no one who knows Baiz, a math teacher at Global Technology Preparatory in Harlem, would dispute that when education reformers talk about wanting to put a high-quality teacher in every classroom, they are talking about teachers like him. In the three years since he “escaped” the Bronx and joined Global Tech, Baiz has emerged as something of a model teacher. Visitors from around the country have flocked to his classroom to see his innovative approach to mixing online tools and old-fashioned instruction. He has helped win the school thousands of dollars in grants. He won a prestigious Math for America fellowship that comes with a $15,000-per-year stipend. He also was selected as one of six New York City teachers to be part of the Digital Teacher Corps, a Ford Foundation-funded collaboration among educators, technologists, and designers to develop interactive digital learning tools aimed at improving student engagement and achievement. And his colleagues have voted him as their union representative.

“David is skilled; he’s always moving forward,” says Chrystina Russell, Global Tech’s principal. Virtually every day “he gives 125 percent.”

But Baiz would be the first to admit that his story isn’t about star power. Indeed, Baiz’s experience is a case study in the importance of collaboration and team work in achieving constant improvement both in teaching and in the overall results for kids. It is also an object lesson in how both TDRs and traditional teacher evaluations can serve to undermine those goals.

Collaboration

Indeed, a recent study by Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations, Collaborating on School Reform, shows that contrary to popular practice and the dictates of many corporate education reformers, the secret to long-term improvement for teachers, schools and students is “substantive collaboration” at all levels—from the classroom to administration to unions. Developing quality teachers, says Saul Rubinstein, an associate professor at Rutgers and one of the authors of the study is about “mentoring, sharing instructional practice, collaborating.” The problem with traditional accountability measures, such as TDRs and punitive performance appraisals, is that they “de-professionalize teaching,” says Rubinstein. The best systems are those that “help teachers succeed.”

Or, as W. Edwards Deming, the quality guru once said, putting the blame for poor performance squarely at the feet of management: There are only two reasons for having deadwood—either you hired deadwood or you hired live wood and you killed it.

Baiz’s story begins at MS 004 in the Bronx—a school from which Global Tech recruited several teachers. Baiz, then-23, was assigned to teach both seventh- and eighth-grade math—an overwhelming assignment for a first-year teacher because it required getting to know two different cohorts of students and to develop two different lesson plans. Weeks into the start of his job, Baiz’s 16-year-old sister was in a catastrophic car accident. Baiz, feeling that “his family needed him,” began making trips back home to Ohio. He was deeply depressed both by what had happened to his sister--she continues to suffer from severe brain injury--and what he and colleagues have describe as a hostile atmosphere at MS 004.

Baiz admits that he was frequently absent that year for which he may have deserved to get a “U” rating.

What happened next is what made the difference not only to keeping Baiz in the teaching profession and helping him excel, but also in building a collaborative school that has fostered a culture of improvement for both teachers and kids. A handful of his more experienced colleagues who had observed Baiz, both in the class room and giving math presentations to the faculty, saw his potential and made a case for keeping him at the school; but Baiz was convinced that his days were numbered. For one thing, the assistant principal who remained determined to get rid of him, was promoted to principal. “He had a hostile administration looking to get rid of him,” says Jackie Pryce-Harvey, a veteran special-education teacher who also worked at MS 004 at the time. “He didn’t stand a chance.”

A Fresh Start

At about the same time, Pryce-Harvey was in the process of persuading her friend, Chrystina Russell, to start a new school, which would eventually become Global Tech. Pryce-Harvey, now Global Tech’s assistant-principal-in-training, recruited Baiz to start working on the planning process. Soon a team of teachers was gathering at Pryce-Harvey’s Harlem brownstone for regular Sunday brunches and, without pay or even the certainty that they would be hired, laying the groundwork for the new school. Russell and her kitchen cabinet poured over budgets and resumes; they developed curricula and a technology strategy for Global Tech, which is a one-to-one laptop school; and they fine-tuned criteria for recruiting teachers.

At Global Tech, which is about to graduate its first eighth-grade class, team-work and collaboration is at the crux of Russell’s efforts to create a holistic system intended to provide support, in ways large and small, for its students, the majority of whom are poor — Global Tech is a universal Title Ischool — and almost all of whom are black or Latino. Baiz teamed up with Valerie Miller, the language teacher who is experimenting with the best ways to use online foreign-language tools, and got a $10,000 grant to develop digital portfolios for the kids. To conserve funds at the school, Russell’s team decided not to hire a dedicated technologist; instead, for the first two years, Baiz agreed to serve as unofficial tech guru working with several teachers to hone their technology skills. Global Tech teachers mentor the teachers-in-training who work for Citizens Schools, the after-school program that Russell sponsors at Global Tech to make sure that kids are off the street until at least 6 p.m. and get homework help and some enrichment. Teachers also collaborate to support the 28 percent of Global Tech students certified as needing special education; Global Tech has moved almost all of them into so-called CTT (Collaborative Team Teaching) classes, where teams of teachers work on everything from students’ special educational needs to helping them with organization skills. The clear expectation is that by the time students graduate eighth grade, most would be able to function in a regular class.

And the teachers routinely work together on initiatives aimed at helping the kids beyond core academics. These include the Saturday test-prep classes the school holds in the weeks before standardized tests, as well as taking the eighth graders to high-school open houses on the weekends, because many of their parents are unable—due to language problems or other issues—to help their children with the high-school application process.

Making the Grade

The results have been impressive. In math, the school ranks in the 84th percentile among all city middle schools. Close to 60 percent of Global Tech students achieved a 3 or 4 in math, the two top levels. And Global Tech, received an A on its latest annual progress report and ranks in the 95 percentile of New York City middle schools. Moreover, virtually everyone loves the school; on its most recent Learning Environment Survey, Global Tech scored well over 90 percent on almost every measure of parent, teacher and student satisfaction. In addition, all Global Tech students who completed the high-school application process have been accepted to a high school, many to their first-choice school.

By contrast, MS 004, Baiz’s alma mater, did far worse on its most recent report card. In math, it ranked in the 58th percentile among city middle schools. Only 44 percent of students achieved a 3 or 4 in math. And the school got a C on its report card. While parent satisfaction at the school was high—over 90 percent in all categories, teacher satisfaction ranged from 46 percent to 83 percent; in response to the statement, “School leaders invite teachers to play a meaningful role in setting goals and making important decisions”, only 64 percent of MS 004 teachers agreed.

Start at the Top

How did the difference in management culture between the two schools impact Baiz? “It’s so much easier to meet the needs of my students,” says Baiz of his experience at Global Tech. The school, he says “is more open to experimentation—it’s more willing to bring in technology and new ideas. I don’t have to worry about watching my back. I don’t have to worry about documenting every little thing. I feel less stress on the job. I don’t have a pit in my stomach every morning. It’s a collaborative relationship.”

Meanwhile, Russell focuses on constantly improving the performance of her teachers. She embraces the Kim Marshall-method of mini-observations, visiting classrooms frequently and giving teachers quick feedback on what they are doing well and where they need to improve. The number-one to-do for Baiz: Improve the pacing of his classes so he doesn’t have to rush at the end, which is hardest on the special education students. As part of the formal teacher-evaluation process, she has teachers observe and critique each other; at periodic meetings, teachers present lesson plans and teaching strategies and discuss ways to improve their practice.

Nor does Global Tech’s approach go easy on teachers who don’t perform up to par. A year ago Russell gave one of her teachers an “Unsatisfactory” because she was habitually tardy, often raised her voice with the kids and didn’t seem comfortable teaching social studies. But Russell didn’t write her off; as she has done with a few other teachers who have struggled, Russell helped the teacher improve her performance. For one thing, when one of the kids told Russell that after attending a Saturday test-prep class with the u-rated teacher, he finally understood what a thesis statement was, Russell sat in on her next test-prep session. Russell was so impressed by what she saw that, for the following year, Russell scheduled the teacher to teach ELA, the subject in which she is certified.

The results, says Russell, have been transformational. She has discovered that the once u-rated teacher had a gift for teaching ELA. “She blows me away; she is doing a phenomenal job,” says Russell who lauds the teacher both for masterful teaching techniques that have helped her students grasp the subject, and for “building great relationships” with the kids.

Russell also views her job as one of protecting her teachers from the constantly shifting mandates of the education bureaucracy. ”So you get your central mandates of whatever stuff you have to do for the year, plus the principal is going to decide whatever thing they're going to do. So teachers just never are shielded from the newest thing is.”

While Global Tech has had the luxury of hand-picking its teachers, evidence suggests that a collaborative and consistent approach to management can achieve similar results in larger long-standing schools and school-districts. Collaboration and consistency are the key themes of the Rutgers study.

Success Story

Similarly, one of the most impressive turnarounds in the country was accomplished at Brockton High, the largest high school in MA, which, like Global Tech, teaches students who are poor, African-American or Latino. Significantly, the transformation was accomplished by the very same teachers who worked at the school when it was failing. Under the leadership of a veteran Brockton history teacher, who became the school’s principal almost a decade ago, Brockton has developed an inclusive teacher-driven approach to improvement and an obsessive focus on literacy that is now over 12-years old. In 1998—75 percent of Brockton’s students failed the state tests in math and 44 percent failed English. On the most recent tests, in 2011, 87 percent of students passed math and 94 percent passed English. Today close to 90 percent of Brockton’s graduates are college bound, estimates Susan Szachowicz, the principal. And, for seven years, Brockton High has been designated a “model school” by the International Center for Leadership in Education.

At Global Tech, where the faculty is much younger, Russell has instituted a long-term career planning process in which she encourages teachers to set out their long-term goals. “If I expect them to move the kids forward,” says Russell. “ I have to be willing to move them forward.”