Preparing for the Great New York Earthquake

Adapted from The Earth Institute and Dr. Lynn Skyes.

Fault lines and known temblors in the New York City region between 1677-2004. The nuclear power plant at Indian Point is indicated by a Pe.

Most New Yorkers probably view the idea of a major earthquake hitting New York City as a plot device for a second-rate disaster movie. In a city where people worry about so much -- stock market crashes, flooding, a terrorist attack -- earthquakes, at least, do not have to be on the agenda.

A recent report by leading seismologists associated with Columbia University, though, may change that. The report concludes a serious quake is likely to hit the area.

The implication of this finding has yet to be examined. Although earthquakes are uncommon in the area relative to other parts of the world like California and Japan, the size and density of New York City puts it at a higher risk of damage. The type of earthquake most likely to occur here would mean that even a fairly small event could have a big impact.

"The issue with earthquakes in this region is that they tend to be shallow and close to the surface," explains Leonardo Seeber, a coauthor of the report. "That means objects at the surface are closer to the source. And that means even small earthquakes can be damaging."

The past two decades have seen an increase in discussions about how to deal with earthquakes here. The most recent debate has revolved around the Indian Point nuclear power plant, in Buchanan, N.Y., a 30-mile drive north of the Bronx, and whether its nuclear reactors could withstand an earthquake. Closer to home, the city adopted new codes for its buildings even before the Lamont report, and the Port Authority and other agencies have retrofitted some buildings. Is this enough or does more need to be done? On the other hand, is the risk of an earthquake remote enough that public resources would be better spent addressing more immediate -- and more likely -- concerns?

Assessing the Risk

The report by scientists from the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University at summarizes decades of information on earthquakes in the area gleaned from a network of seismic instruments, studies of earthquakes from previous centuries through archival material like newspaper accounts and examination of fault lines.

The city can expect a magnitude 5 quake, which is strong enough to cause damage, once every 100 years, according to the report. (Magnitude is a measure of the energy released at the source of an earthquake.) The scientists also calculate that a magnitude 6, which is 10 times larger, has a 7 percent chance of happening once every 50 years and a magnitude 7 quake, 100 times larger, a 1.5 percent chance. Nobody knows the last time New York experienced quakes as large as a 6 or 7, although if once occurred it must have taken place before 1677, since geologists have reviewed data as far back as that year.

The last magnitude 5 earthquake in New York City hit in 1884, and it occurred off the coast of Rockaway Beach. Similar earthquakes occurred in 1737 and 1783.

By the time of the 1884 quake, New York was already a world class city, according to Kenneth Jackson, editor of The Encyclopedia of New York City."In Manhattan," Jackson said, "New York would have been characterized by very dense development. There was very little grass."

A number of 8 to 10 story buildings graced the city, and "in world terms, that's enormous," according to Jackson. The city already boasted the world's most extensive transportation network, with trolleys, elevated trains and the Brooklyn Bridge, and the best water system in the country. Thomas Edison had opened the Pearl Street power plant two years earlier.

All of this infrastructure withstood the quake fairly well. A number of chimneys crumbled and windows broke, but not much other damage occurred. Indeed, the New York Times reported that people on the Brooklyn Bridge could not tell the rumble was caused by anything more than the cable car that ran along the span.

Risks at Indian Point

As dense as the city was then though, New York has grown up and out in the 124 years since. Also, today's metropolis poses some hazards few, if any people imagined in 1884.

In one of their major findings, the Lamont scientists identified a new fault line less than a mile from Indian Point. That is in addition to the already identified Ramapo fault a couple of miles from the plant. This is seen as significant because earthquakes occur at faults and are the most powerful near them.

This does not represent the first time people have raised concerns about earthquakes near Indian Point. A couple of years after the licenses were approved for Indian Point 2 in 1973 and Indian Point 3 in 1975, the state appealed to the Atomic Safety and Licensing Appeal Panel over seismic issues. The appeal was dismissed in 1976, but Michael Farrar, one of three members on the panel, dissented from his colleagues.

He thought the commission had not required the plant to be able to withstand the vibration that could occur during an earthquake. "I believe that an effort should be made to ascertain the maximum effective acceleration in some other, rational, manner," Farrar wrote in his dissenting opinion. (Acceleration measures how quickly ground shaking speeds up.)

Con Edison, the plants' operator at the time, agreed to set up seismic monitoring instruments in the area and develop geologic surveys. The Lamont study was able to locate the new fault line as a result of those instruments.

Ironically, though, while scientists can use the data to issue reports -- the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission cannot use it to determine whether the plant should have its license renewed. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission only considers the threat of earthquakes or terrorism during initial licensing hearings and does not revisit the issue during relicensing.

Lynn Sykes, lead author of the Lamont report who was also involved in the Indian Point licensing hearings, disputes that policy. The new information, he said, should be considered -- "especially when considering a 20 year license renewal."

The state agrees. Last year, Attorney General Andrew Cuomo began reaching out to other attorneys general to help convince the commission to include these risks during the hearings.

Cuomo and the state Department of Environmental Conservation delivered a 312-page petition to the commission that included reasons why earthquakes posed a risk to the power plants. The petition raised three major concerns regarding Indian Point:

- The seismic analysis for Indian Point plants 2 and 3 did not consider decommissioned Indian Point 1. The state is worried that something could fall from that plant and damage the others.

- The plant operators have not updated the facilities to address 20 years of new seismic data in the area.

- The state contends that Entergy, the plant's operator, has not been forthcoming. "It is not possible to verify either what improvements have been made to [Indian Point] or even to determine what improvements applicant alleges have been implemented," the petition stated.

A spokesperson for Entergy told the New York Times that the plants are safe from earthquakes and are designed to withstand a magnitude 6 quake.

Lamont's Sykes thinks the spokesperson must have been mistaken. "He seems to have confused the magnitude scale with intensity scale," Sykes suggests. He points out that the plants are designed to withstand an event on the intensity scale of VII, which equals a magnitude of 5 or slightly higher in the region. (Intensity measures the effects on people and structures.) A magnitude 6 quake, in Sykes opinion, would indeed cause damage to the plant.

The two reactors at Indian Point generate about 10 percent of the state's electricity. Since that power is sent out into a grid, it isn't known how much the plant provides for New York City. Any abrupt closing of the plant -- either because of damage or a withdrawal of the operating license -- would require an "unprecedented level of cooperation among government leaders and agencies," to replace its capacity, according to a 2006 report by the National Academies' National Research Council, a private, nonprofit institution chartered by Congress.

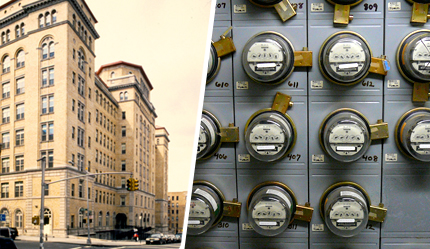

Photo (courtesy of) Tony the Misfit.

Entergy's Indian Point Energy Center, a three-unit nuclear power plant north of New York City, lies within two miles of the Ramapo Seismic Zone.

Beyond the loss of electricity, activists worry about possible threats to human health and safety from any earthquake at Indian Point. Some local officials have raised concerns that radioactive elements at the plant, such as tritium and strontium, could leak through fractures in bedrock and into the Hudson River. An earthquake could create larger fractures and, so they worry, greater leaks.

In 2007, an earthquake hit the area surrounding Japan's Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear power plant, the world's largest. The International Atomic Energy Agency determined "there was no significant damage to the parts of the plant important to safety," from the quake. According to the agency, "The four reactors in operation at the time in the seven-unit complex shut down safely and there was a very small radioactive release well below public health and environmental safety limits." The plant, however, remains closed.

Shaking the Streets

A quake near Indian Point would clearly have repercussions for New York City. But what if an earthquake hit one of the five boroughs?

In 2003, public and private officials, under the banner of the New York City Area Consortium for Earthquake Loss Mitigation, released a study of what would happen if a quake hit the metropolitan area today. Much of the report focused on building damage in Manhattan. It used the location of the 1884 quake, off the coast of Rockaway Beach, as its modern muse.

If a quake so serious that it is expected to occur once every 2,500 years took place off Rockaway, the consortium estimated it would cause $11.5 billion in damage to buildings in Manhattan. About half of that would result from damage to residential buildings. Even a moderate magnitude 5 earthquake would create an estimated 88,000 tons of debris (10,000 truckloads), which is 136 times the garbage cleared in Manhattan on an average day, they found.

The report does not estimate possible death and injury for New York City alone. But it said that, in the tri-state area as a whole, a magnitude 5 quake could result in a couple of dozen deaths, and a magnitude 7 would kill more than 6,500 people.

Ultimately, the consortium decided retrofitting all of the city's buildings to prepare them for an earthquake would be "impractical and economically unrealistic," and stressed the importance of identifying the most vulnerable areas of the city.

Unreinforced brick buildings, which are the most common type of building in Manhattan, are the most vulnerable to earthquakes because they do not absorb motion as well as more flexible wood and steel buildings. Structures built on soft soil are more also prone to risk since it amplifies ground shaking and has the potential to liquefy during a quake.

This makes the Upper East Side the most vulnerable area of Manhattan, according to the consortium report. Because of the soil type, the ground there during a magnitude 7 quake would shake at twice the acceleration of that in the Financial District. Chinatown faces considerable greater risk for the same reasons.

The city's Office of Emergency Management agency does offer safety tips for earthquakes. It advises people to identify safe places in their homes, where they can stay until the shaking stops, The agency recommends hiding under heavy furniture and away from windows and other objects that could fall.

A special unit called New York Task Force 1 is trained to find victims trapped in rubble. The Office of Emergency Management holds annual training events for the unit.

The Buildings Department created its first seismic code in 1995. More recently, the city and state have adopted the International Building Code (which ironically is a national standard) and all its earthquake standards. The "international" code requires that buildings be prepared for the 2,500-year worst-case scenario.

Transportation Disruptions

With the state's adoption of stricter codes in 2003, the Port Authority went back and assessed its facilities that were built before the adoption of the code, including bridges, bus terminals and the approaches to its tunnels. The authority decided it did not have to replace any of this and that retrofitting it could be done at a reasonable cost.

The authority first focused on the approaches to bridges and tunnels because they are rigid and cannot sway with the earth's movement. It is upgrading the approaches to the George Washington Bridge and Lincoln Tunnel so they will be prepared for a worst-case scenario. The approaches to the Port Authority Bus Terminal on 42nd Street are being prepared to withstand two thirds of a worst-case scenario.

The terminal itself was retrofitted in 2007. Fifteen 80-foot tall supports were added to the outside of the structure.

A number of the city's bridges could be easily retrofitted as well "in an economical and practical manner," according to a study of three bridges by the consulting firm Parsons Brinckerhoff. Those bridges include the 102nd Street Bridge in Queens, and the 145th Street and Macombs Dam bridges, which span the Harlem River. To upgrade the 155th Street Viaduct, the city will strengthen its foundation and strengthen its steel columns and floor beams.

The city plans upgrades for the viaduct and the Madison Avenue bridge in 2010. The 2008 10-year capital strategy for the city includes $596 million for the seismic retrofitting of the four East River bridges, which is planned to begin in 2013. But that commitment has fluctuated over the years. In 2004, it was $833 million.

For its part, New York City Transit generally is not considering retrofitting its above ground or underground structures, according to a report presented at the American Society of Civil Engineers in 2004. New facilities, like the Second Avenue Subway and the Fulton Transit Center will be built to new, tougher standards.

Underground infrastructure, such as subway tunnels, electricity systems and sewers are generally safer from earthquakes than above ground facilities. But secondary effects from quakes, like falling debris and liquefied soil, could damage these structures.

Age and location -- as with buildings -- also add to vulnerability. "This stuff was laid years ago," said Rae Zimmerman, professor of planning and public administration at New York University. "A lot of our transit infrastructure and water pipes are not flexible and a lot of the city is on sandy soil." Most of Lower Manhattan, for example, is made up of such soil.

She also stresses the need for redundancy, where if one pipe or track went down, there would be another way to go. "The subway is beautiful in that respect," she said. "During 9/11, they were able to avoid broken tracks."

Setting Priorities

The city has not made preparing its infrastructure for an earthquake a top priority -- and some experts think that makes sense.

"On the policy side, earthquakes are a low priority," said Guy Nordenson, a civil engineer who was a major proponent of the city's original seismic code, "and I think that's a good thing." He believes there are more important risks, such as dealing with the effects of climate change.

"There are many hazards, and any of these hazards can be as devastating, if not more so, than earthquakes," agreed Mohamed Ettouney, who was also involved in writing the 1995 seismic code.

In fact, a recent field called multi-hazard engineering has emerged. It looks at the most efficient and economical way to prepare for hazards rather than preparing for all at once or addressing one hazard after the other. For example, while addressing one danger (say terrorism) identified as a priority, it makes sense to consider other threats that the government could prepare for at the same time (like earthquakes).

Scientists from Lamont-Doherty are also not urging anybody to rush to action in panic. Their report is meant to be a first step in a process that lays out potential hazards from earthquakes so that governments and businesses can make informed decisions about how to reduce risk.

"We now have a 300-year catalog of earthquakes that has been well calibrated" to estimate their size and location, said Sykes. "We also now have a 34-year study of data culled from Lamont's network of seismic instruments."

"Earthquake risk is not the highest priority in New York City, nor is dog-poop free sidewalks," Seeber recently commented. But, he added, both deserve appropriately rational responses.

Â

Climate Change Could Threaten a Green Willets Point

Photo by Francesco Trovato

Adjacent to the Mets' new home at Citi Field, Willets Point houses the New York area's largest concentration of auto repair and service businesses, the nation's biggest distributor of Indian foods and several waste transfer facilities. All that could change dramatically, though, if the Bloomberg administration has its way and transforms the area into the city's first "green" neighborhood.

The mayor's proposal has raised the ire of local business owners and housing advocates, who decry the plan's use of eminent domain to seize the commercial property and contend that it does not include enough affordable housing. Those opponents turned out in full force on Wednesday at the City Planning Commission's public hearing on the project.

Small business owners and community activists waved signs condemning the use of eminent domain, while shouting "Willets Point is not for sale."

The commission is in the process of a 60-day review period on the project. It must make a decision by September 29. If approved, the City Council would then take over, making the ultimate up or down choice on the sprawling development. The outcome of that decision is anyone's guess, since a number of City Council members (including Councilmember Hiram Monserrate who represents the area) strenuously oppose the project.

Surprisingly, amid all the controversy swirling around Willets Point, very few have questioned whether the city's "first green neighborhood" will eventually be submerged by water.

Known as "the Iron Triangle," Willets Point is legendary for the vast potholes that punctuate its barely paved streets and its lack of a modern sewer system. Evidence of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), heavy metals, pesticides, herbicides and rodenticides also have been found throughout the district. No one disagrees that the area is sorely in need of improvement. In fact, local business owners have lobbied the city for years to repair potholes and install an updated sewer system. But the city has maintained that because the area is located in a flood plain, it cannot install a sewer system with the current owners in place.

Then in 2007, city officials announced a long-awaited solution to the problems in Willets Point -- a $3 billion plan to seize 61 acres of the district, raze it, and construct a hotel, convention center, 5,500 units of housing (80 percent of which will be market-rate) and over 2 million square feet of office space, as well as restaurants, a movie theater and retail shops. Even more ambitiously, the city intends to transform Willets Point into New York City's "first green neighborhood," with trees, bike paths and parks, state-of-the-art energy efficient buildings, innovative water management (including the use of green roofs and "graywater systems") and public-transit oriented development. In short, the project fulfills many of the goals outlined in PlaNYC 2030.

The Opposition

But local business owners are not so optimistic about the transformation of Willets Point. On hearing about the plan, they immediately organized to protect their property from eminent domain. They filed a lawsuit accusing the city of "negligent, reckless and willful refusal" to provide infrastructure with the ultimate goal of declaring the area blighted, a condition that can trigger eminent domain. Instead, business owners want the city to fix existing infrastructure and revitalize the area without removing businesses. Many worry that moving to other parts of the city could jeopardize their businesses.

In April, 29 of 51 City Council members signed a letter demanding that the administration "stop the clock" on the land use -- or ULURP -- process to approve the plan. Initiated by Monserrate, the letter states, "We adamantly oppose moving forward with the current redevelopment plan for Willets Point. The plan is deeply flawed, and the opportunity for public consideration has been dangerously absent. We disagree with your decision to pursue ULURP certification for this project. As elected officials, we urge you to reconsider this plan and to engage in a more accessible and transparent process." This week another letter, saying they couldn't vote for the project as is, was sent to the commission with 32 members signed on.

City Council members might also question the administration's definition of "sustainable." Willets Point sits in a flood plain and is close to Flushing Creek and Flushing Bay. Climate experts warn that increased storms and flooding due to climate change pose a potentially dire future for waterfront projects such as Willets Point. Does sustainability end at the year 2030? For how many future generations is PlaNYC 2030 planning?

The Fill and The Flood

"Two of the greatest challenges [at Willets Point] are site contamination and site elevation," states the New York City Economic Development Corporation's Environmental Impact Statement. To address that problem, the city plans to install up to six feet of fill prior to site redevelopment.

The fill will be used to "cap" contamination at the site, sealing toxins underneath a mound of new dirt. The effectiveness of this method for containing contamination is debatable. Caps need to be carefully maintained against the effects of erosion, especially in low-lying areas. More significantly, a report by the Canada's Contaminated Sites Working Group maintains that capped areas are never suitable for further development as capping carries a risk of leakage. Again, low-lying areas close to waterways and estuaries magnify this risk.

"There are good, current and acceptable methods for evaluating these impacts, but the project sponsor has not considered any of them," says climate change expert Linda Sohl in a prepared statement released by the project's opponents. "Furthermore, all of lower Manhattan, including the World Trade Center site and most waterfront land in New York City is in the 100-year flood plain - for some reason the city is not concerned with elevating these areas with fill."

Her words raise concerns about whether six feet of fill is adequate. At less than 14 feet above sea level, Willets Point now lies well within the Federal Emergency Management Agency's designation for a 100-year floodplain -- an area with a 100 percent chance of flooding during a flood that has a 1 percent chance of occurring during any given year. Right now, FEMA's threshold for a floodplain is 14 feet above sea level. Six feet of fill raises Willets Point to between 14 and 17 feet above sea level -- not far from the federal threshold.

The International Panel on Climate Change predicts that East Coast sea levels will rise by one to three feet by the year 2100, depending on how well we reduce the greenhouse gas emissions that cause global warming. Certainly, a three-foot rise in sea level will not put Willets Point under water. The problem is that even a one-foot rise in sea level (the best case scenario) will likely double the frequency of coastal surging and related flooding. In other words, even if we reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 30 percent, the Union of Concerned Scientists predicts that by 2100, 100-year floods could occur an average of every 22 years. Moreover, researchers at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory warn that we will almost certainly see storm surges of more than 20 feet.

Economic Development Corporation officials maintain that the proposed elevations will protect the area from current and future threats of floods. Going a step further, they pledge to keep the area out of floodplain designations, should FEMA update them in the future, although they do not offer any specifics on how they would do that. Development corporation officials also stated that they would adhere to all governmental guidelines including those set by the Department of Buildings and the Department of Environmental Protection, especially as those guidelines shift in light of climate change. Of course, PlaNYC2030, itself, was designed in part to "create a strategic planning process to adapt to climate change impacts."

Beyond that, though, the plan hopes to limit climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 30 percent by the year 2030. As a result, building a whole new community -- even a sustainable one -- at Willets Point poses an apparent contradiction since constructing a new 50,000-square foot commercial building releases about the same amount of carbon into the atmosphere as driving a car 2.8 million miles.

"No matter how much green technology is employed in its design and construction, any new building represents a new impact on the environment," explains Richard Moe, president of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. At the same time, improving existing buildings and infrastructure almost always produces a lower level of emissions.

In the case of Willets Point, the development offers a particularly ironic twist. In seeking to build New York City's first "green" neighborhood, the city could instead add to global warming and endanger that very same community.

ÂFighting the Asian Long-Horned Beetle

Like a monster in a sci-fi movie, an invading black-and-white beetle with outsized striped antennae has the potential to undo the city's efforts to plant a million more trees. The Asian long-horned beetle could kill nearly half the city's hardwood trees and spell disaster for the Northeast's forests, parks officials say.

A tree-killing attack starts when the beetle chews holes in the bark of a tree to lay its eggs. The eggs hatch into larvae that bore into the heartwood, where they live and feed during the colder months before emerging as adults in the spring. The Asian long-horned beetle infests many different kinds of hardwoods, including all maple species, birch, horse chestnut, London plane, sycamore, poplar, willow, elm and ash.

It is believed that the beetle hitched a ride in wooden packing material shipped from China. The first New York sighting of the beetle was in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, in 1996. Since then, it has been found in all boroughs except the Bronx, as well as in Long Island and New Jersey. (A separate infestation discovered in Chicago in 1998 was recently declared eradicated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.)

Attack on Staten Island

Last year, the invader made inroads into Staten Island for the first time, using Prall's Island, an uninhabited bird sanctuary in the Arthur Kill, as a stepping stone. At the time Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe warned that, if left unchecked, the beetle "could wipe out .... half of the trees of Staten Island, which would completely change the character of the island."

Federal and state agencies and the city parks department quickly mounted an intensive control effort. Parks workers cut down and chipped nearly 3,000 trees on Prall's Island and 6,700 trees on the nearby Staten Island shore, destroying infested trees as well as any tree that could be a potential host within a half-mile radius.

In Staten Island and all the areas where the pest has been discovered, the state and federal agencies conduct year-round surveying for evidence of infestation; in the spring, insecticide is injected into potential host trees within a mile and a half of known infestations.

This past spring, a parks department restoration team began replanting new trees, shrubs and native plants on Prall's Island.

The eradication efforts appear to have halted the Asian long-horned beetle's advance in Staten Island, and so far this year no new infestations have been reported anywhere in New York City.

To prevent the inadvertent spread of the beetle, the parks department also provides free pick-up, chipping and disposal of residential wood waste in the four boroughs where the pest has been found.

The Government and the Public

In spite of the seriousness of the threat, federal funding to fight the beetle in New York City has been cut in recent years. For next year, Rep. Anthony Weiner is asking for $48 million for the federal beetle eradication program, $30 million of which would go to the city.

"New York City is the central point of infestation," Weiner said at a press conference earlier this year. But, he added, ""If we don't stop this, it won't be only a New York City problem."

Even if Washington did step up its support, the parks department would be unable to survey the city's more than 5 million trees in streets, parks and yards. As a result, the eradication effort depends on the public. Anyone who suspects an infestation should call the toll-free number 1-877-STOPALB or 311.

The beetle is one to one-and-a-half inches long, with a shiny black body, white spots and very long, black-and-white striped antennae. Telltale evidence of an infestation includes dime or pencil-sized holes, usually in a tree's upper trunk or branches, and piles of frass (sawdust and insect waste) at the base of a tree or where branches meet the trunk.

For more information, check the Web sites of the New York City parks department and U.S. Department of Agriculture's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service.

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

New Bills: From Saving Energy to Preventing Choking

While the City Council continues to focus on construction hazards in the city, individual council members have kept their eye on other legislative prospects. They have offered common sense solutions to quality of life issues, proposals to conserve energy in the summer and various offbeat initiatives likely to flounder in City Hall.

This is just a sampling of the City Council bills introduced in the last month.

Family Leave Act

Nationwide, less than 10 percent of workers get paid time off to care for sick family members, according to the Working Families Party. Though the federal Family and Medical Leave Act offers 12 unpaid weeks, about two thirds of those eligible do not take the time because they cannot afford to, according to a study by the U.S. Department of Labor.

Letitia James, the only council member elected on the Working Families Party line, introduced legislation (Intro 805) to give private employees 12 paid weeks off to care for sick family members. The bill would cover a range of relatives, from nieces to spouses. The party has proposed a similar measure on the state level.

James, who cares for her mother, said she has the discretion to leave work to take care of a family emergency. Others, especially those with both parents and children to care for, do not.

"I wanted to provide some relief for baby boomers and for others who are just juggling family and work," said James.

According to the bill, private employers would be able to use accrued sick time or disability to pay for the employees' time off. James said supporters have not yet studied the cost of the bill. Unlike the federal unpaid act, which applies to companies with more than 50 employees, James's bill does not have a restriction on the size of the business.

The legislation would also prevent employers from retaliating against employees, by terminating their positions, for example, because they take leave.

On the state level, the legislation would be funded by increasing disability insurance.

California, New Jersey and Washington State are the only states that offer paid family leave.

Sustainable Street Lamps

To reduce the city's consumption of energy, Councilmember Jessica Lappin of Manhattan introduced legislation (Intro 806) requiring the city replace its current street lamps with light-emitting diode street lamps.

Diode street lamps can reportedly reduce energy consumption by 70 percent. Other cities are testing similar technology.

Within one year of the bill's potential approval, according to the legislation, all of the city's street lamps would have to use diode bulbs.

Dangerous Foods

Approximately two years ago, a young child in Brooklyn choked to death on a grape. To increase awareness of choking hazards, Councilmember Domenic Recchia introduced legislation (Intro 807) requiring the labeling of food that are choking hazards.

Similar legislation was introduced in Albany in 2004 after a 3-year-old choked to death on a popcorn kernel.

Under the bill, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene would compile a list of foods that present a significant choking hazard to children ages 5 and below. Those foods would need to have a warning label.

A spokesman for Recchia said the Department of Consumer Affairs would be charged with enforcement. It is likely, he added, storeowners would be responsible for ensuring dangerous foods were labeled, not farmers or national vendors.

A cost analysis of the bill has not yet been completed.

Tracking the Emotionally Disturbed

After a series of incidents late last year involving mentally or emotionally disturbed individuals creating disruptions or acting violently, which in one incident led to the shooting of an unarmed man by police, calls for action trickled in from communities.

In response, Councilmember Peter Vallone introduced legislation (Intro 799) calling for the creation of a database, to be overseen by the New York Police Department and the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, that would keep tabs on the "emotionally disturbed."

The database would include, at a minimum, the name, address and nature of the incident involving an "emotionally disturbed" person. It would file incidents where individuals were transported to a hospital.

According to the legislation, the police department made more than 87,000 radio runs in 2007 that involved an "emotionally disturbed" person.

A Vallone spokesperson said the database would help police and health officials spot trends and identify people who needed help.

Clean Elections

After an overhaul of the city's campaign finance legislation last year, Councilmember Tony Avella is looking to take the city's law one step further by decreasing limits to receive public financing.

Under the bill (Intro 803), which Avella has titled the "Clean Elections Law," City Council candidates would have to raise just $2,500, consisting of small donations from $5 to $100, to qualify for $100,000 in public financing for the primary and an additional $100,000 for the general election. The bill would also limit contributions that could be matched with public dollars to less than $100.

The legislation reduces overall spending caps for every city office and lowers public financing requirements for all citywide offices. In a prepared statement, Avella said the restrictions would reduce the influence of special interest money, which flood campaigns with large, bundled donations.

"Under the current system the playing field isn't leveled," said Avella in a press release. "It's actually tilted."

Under the bill, which has garnered one other sponsor, Councilmember Joseph Addabbo, City Council candidates would also have to commit to two debates.

Delaying Health Fines for Nonprofits

Under a bill introduced by Councilmember Vincent Gentile (Intro 791) nonprofits, including religious and cultural groups, would get extra time to remedy health code violations before paying a fine.

"The intention is not to exempt these organizations from following the law," said the councilmember's budget and legislative director, John Buckholz. "It's to reduce the financial burden that’s imposed on them."

Yellow Curb Cuts

While some parts of the city are covered with illegal curb cuts that slice away front lawns, Councilmember Michael McMahon wants to protect the legal ones.

Under a bill (Intro 797) introduced by McMahon, property owners would be allowed to paint their curb cuts yellow. It would be a clear warning sign to other parkers not to block driveways.

Taking the LEED on Capital Projects

Councilmember Joel Rivera introduced legislation (Intro 798) requiring capital projects comply with most standards of the U.S. Green Building Council's Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Green Building Rating System, an accredited measurement of green building.

Any project that receives partial or full funding from public coffers and costs more than $5 million would have to comply with some portion of the standards. As a project's cost increases, a contractor would have to comply with more standards under the bill.

Energy Efficiency Disclosure

A bill (Intro 800) introduced by Councilmember Al Vann would require any owner of a condominium, co-op or one to four family home notify prospective buyers of the property's energy efficiency, including the monthly cost of the electric bill for the previous two years.

Transparency at Children's Services

A bill (Intro 804) introduced by Councilmember Bill de Blasio would require the Administration for Children's Services submit quarterly reports to the City Council on day care closures and the average time it takes, from application to placement, for a child to receive daycare.

Â

On the Beaches

ALSO:

The Bronx's Secret Shore:

Unbeknownst to the vast majority of its residents, the Bronx serves as home to a number of private beach clubs.

Whistle While You Work:

The job is outside, you wear a bathing suit -- and the city usually has openings.

Coney Island Roller Coaster:

The fight over how to develop the famed beach continues.

Urban Riviera?

New York's beaches offer surf and sun without a long drive on the Long Island Expressway. But how safe and clean are they?

New York's Best and Worst Beaches:

They are both on Staten Island but there the similarities end.

With eight public beaches in the city, New Yorkers do not have to venture far from home to smell the salt air and sunblock. But does our Urban Riviera really offer a respite for residents fed up with the cement landscape and longing for fresh ocean air and soft sea breezes? And how clean and safe are the beaches -- seven city and one federal?

Gotham Gazette's audio slide presents words and images from some of the city's most popular beaches, as beachgoers critique the scene around them, from litter to accessibility to jellyfish.

To view the audio slide show, go here.

Beach Map: Sounds from the Surf

Call it the heat island effect or the draw of fun in the sun, the desire for sand between your toes and salt in your skin hits many of us during the summer. While some New Yorkers spend their days drowning in traffic on the way to the Hamptons, others recognize we have seven city public beaches and many more private facilities right here in the five boroughs.

Map courtesy of New Yorkers for Parks, photo by YH Huang

TAKE YOUR PICK:

There's the vivacious and crowded Coney Island or its more subdued neighbors, Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach.

Head to Rockaway Beach in Queens and dip your toes in the Atlantic where few remnants of New York City, besides the A train, remain.

Feeling adventurous? Take the ferry, then a train and maybe a long walk (see related story) on Staten Island, which boasts three city beaches: Midland and South Beaches as well as Wolfe's Pond Beach.

Then there's Orchard Beach, tucked into Pelham Bay Park, the only public beach on Long Island Sound.

If none of those satisfy, meander through Jacob Riis Park, a federal beach in the city, or check out the many private beaches that line our urban coastline.

Sounds from the Surf

South Beach, Staten Island

Midland Beach, Staten Island

Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn

Â

New York's Best and Worst Beaches

Photos by Olivia Warren and YH Huang

Wolfe's Pond Beach, left, and Midland Beach, right, both on Staten Island.

ALSO:

Touring the Urban Riviera:

An audio slide show of New York's public beaches.

The Bronx's Secret Shore:

Unbeknownst to the vast majority of its residents, the Bronx serves as home to a number of private beach clubs.

Whistle While You Work:

The job is outside, you wear a bathing suit -- and the city usually has openings.

Coney Island Roller Coaster:

The fight over how to develop the famed beach continues with fate of the famed rides and amusements at stake.

Urban Riviera?

New York's beaches offer surf and sun without a long drive on the Long Island Expressway. But how safe and clean are they?

Midland Beach and Wolfe's Pond Beach are both on Staten Island and operated by the city's parks department. Roughly the same size, they both stretch about one and a half miles along the shoreline. And on a Monday afternoon in July, the two beaches each boasted one lone swimmer bobbing up and down amid the waves. The similarities ended there, according to New Yorkers for Parks. In its 2007 Report Card on Beaches, the group ranked Midland Beach the best in New York City. Wolfe's Pond Beach came in last.

New Yorkers for Parks, an independent watchdog group, began releasing its Report Card on Beaches in 2003. The rating assesses the seven beaches controlled by the parks department, comparing them to one another as well as from year to year. The group grades beaches on four features: quality of shoreline and condition of pathways, bathrooms and drinking fountains.

In the 2007 rankings, Midland Beach was the only beach that received an overall ranking of "Satisfactory." Four other beaches were deemed "Challenged" and the remaining two, including Wolfe's Pond, were "Unsatisfactory." (The other unsatisfactory beach was Coney Island.)

An Eyewitness Account

Curious about the best and worst beaches in the city -- and how such disparate facilities could be in such close proximity to each other-- Gotham Gazette decided to investigate.

The first thing we discovered was that the age-old mantra of life being about the journey and not the destination is painfully true when heading to Staten Island's beaches. Without a car, there is simply no easy way to access the beaches. Both beaches are at least a 20-minute walk from the nearest express bus stop or the Staten Island Railroad.

Midland Beach

Photos by Olivia Warren

Midland Beach had the highest performance rating of any shoreline, and the report noted minimal litter and debris along the beach. The Report Card found the pathways a minor challenge, facing overgrowth and warping or breaking of the asphalt. The bathrooms received a grade of 65 percent due to general disrepair. Drinking fountains at Midland Beach ranked best of those at any beach, though they still only received a "D" because of poor structure and repairs.

Upon arrival at Midland Beach, it was quickly apparent as to why it scored well. With over 300,000 visitors a year, the beach offers an impressive expanse of well maintained somewhat orange sand leading down to the water. Sturdy woven plastic mats stretch across the sands leading to the water, making the beach easily accessible by wheelchair. Families push strollers down the mats and then lift them onto a nearby spot in the sand.

A clearly marked bike path and walkway border the beach. The promenade features benches and drinking fountains, as well as a fountain with a prominent sculpture of a sea turtle where children leap about and dodge the squirting streams of water. The park includes playgrounds, a baseball diamond, more benches and shaded areas, among other amenities.

"Minimal" presence of litter, as the Report Card phrases it, can be a relative term, and there were wrappers and plastic bottles in the sand nearest to the water. The rest of the area was cleaner, though, and trashcans were not overflowing. Ten lifeguards surveyed the scene, and most families clustered around their towers. The sound of laughter and children shrieking things like "I see a whale!" followed by "No, it's a shark!" carried along the light breeze, as did a slight fishy odor.

The bathrooms were a bit dark and wet, but each stall had toilet paper, and the sink area had soap and a working hand dryer. The showers were also in good condition, and there was a covered changing area. Drinking fountains were few and far between, and seemed to be in fairly poor condition.

Peter, a lifeguard, said that the beach is frequented mostly by families and gets especially busy on the weekends. He cited the murkiness of the water as the area's only drawback.

That murkiness did not seem to concern Mona Lozah and her three children. A resident of Staten Island, she said that she prefers Midland to the nearby South Beach or Coney Island Beach, the other two parks department beaches she has visited. When asked why, she said, "Parking!" and gestured to the massive and almost empty parking lots. She also praised the beach for its cleanliness, lack of insects and family friendliness. Her kids, totally absorbed in their construction of a sand castle, seemed to agree.

Wolfe's Pond Beach

Photos by Olivia Warren

No laughter rang across Wolfe's Pond Beach. In fact, there were no sounds on a July day except the wind, the waves and a circling police helicopter. The entire shore was littered with seaweed, shells and driftwood, as well as broken glass, empty alcohol bottles, a gallon jug of bleach, an old tire, and a rusting metal folding chair. The smell of fish was far more than slight. We could not find the two informal ramps that the parks department Web site says can be used for wheelchair access.

While the Report Card noted that the section of shore open to the public at Wolfe's Pond was well maintained, it cited overwhelming debris, including safety hazards such as glass, as the reason for the shoreline's failing grade. The pathways were rated on par with the rest of the beaches, but New Yorkers for Parks found the bathrooms were closed and locked, accounting for their failing score. There are no drinking fountains on the beach, though there are plenty to be found in the adjoining Wolfe's Pond Park.

Photos by Olivia Warren

Three lifeguards were on duty for the miniscule stretch of beach open for swimming. Pointing to the piles of debris covering the sand near the water, the lifeguards, who would not give their names, said that beachgoers needed to wear shoes or water shoes at all times for safety. When asked if people swim in the water, they replied "Unfortunately." On its Web site, the parks department mentions the large amount of seaweed at the beach, but that seemed to be an understatement as each wave turned over fresh mounds of green leafy plants.

Asked to name the best part of the beach, one lifeguard cited the lifeguards. More seriously, another replied, "The park."

Photos by Olivia Warren

A lone swimmer at Wolfe's Pond

Sure enough, walking up the worn wooden steps to the park seemed like entering another world. Manicured lawns led into playgrounds and picnic areas where families barbecued. Teenagers skated around a roller hockey rink or swatted balls at the tennis courts. Clean drinking fountains and bathrooms abounded.

Better Beaches?

In response to reports on conditions at Wolfe's Pond and other beaches, the parks department cites statistics from its own Parks Inspection Program, which, it says, shows conditions have been improving. "By every measure, New York City's beaches are in better shape now than at any other time," a spokesperson said. However, the department acknowledges that "litter on public beaches is a primary concern" and asks the public to help.

Our visits did show improvement at the Staten Island beaches since last year's Report Card was compiled. Midland Beach had been using one bathroom as a storage space for desks, according to the report. This year, there was no furniture to be found.

New Yorkers for Parkers marked down Wolfe's Pond Beach for not having signs barring swimming in closed areas. This year, behind some trees, you could read a sign that said "Swimming Prohibited: No Lifeguard on Duty."

Beachgoers will more than likely obey.

Â

Keeping City Beaches Safe and Clean

Photo by Courtney Gross

ALSO:

Touring the Urban Riviera:

An audio slide show of New York's public beaches.

The Bronx's Secret Shore:

Unbeknownst to the vast majority of its residents, the Bronx serves as home to a number of private beach clubs.

Whistle While You Work:

The job is outside, you wear a bathing suit -- and the city usually has openings.

Coney Island Roller Coaster:

The fight over how to develop the famed beach continues with fate of the famed rides and amusements at stake.

New York's Best and Worst Beaches:

They are both on Staten Island but there the similarities end.

Music throbs from the cement steps as gawkers line railings and eye young women in bikinis at the Bronx's Orchard Beach. Umbrellas and sunbathers stretch out seemingly for miles -- tiny specs of blue, red and yellow, loaded with sunscreen and wide-rimmed sunglasses.

It's July. It's Saturday, and the city has turned out to catch some sun.

Among those sunbathers are Silvia and Paul Martinez, a brother and sister from Castle Hill who have made the Bronx's only public beach a routine visit during their summer days. Silvia, 18, may enjoy Orchard Beach, but she wasn't shy about admitting its drawbacks.

"We're not going to deny it," Silvia said as she eyed her sibling splashing in the waves. "It's dirty."

That perception is not uncommon.

While the seven city parks department beaches meet federal health standards and attracted an estimated 15 million visitors last year, they have their shortcomings. It's the litter, and it's the water quality, say beachgoers. Overall, our city beaches have an inferior reputation -- some say unjustly -- compared to suburban sunbathing spots.

Officials, advocates and others argue the city shore offers amenities you can't get on Long Island -- swimming with a view of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge or being able to leave nature's waves for the ups and downs of The Cyclone -- and the quality of its facilities has improved.

Urban beaches, though, pose special challenges for the parks officials who run them. The shore offers relief from our cement landscape but it also is very much a part of the city. That gives the beaches a kind of gritty charm but also presents huge problems in terms of pollution, debris and ordinary litter.

Sewage Water

Photo by Courtney Gross

As the Mermaid Parade trekked down Coney Island's boardwalk last month -- solidifying the start of the city's official beach season -- Joyce and Peter Jagassar of the Bronx poured beer into plastic cups and dug their feet into the sand.

The Jagassars travel nearly two hours to Coney Island because they think it's cleaner than their own borough's Orchard Beach. Even at Coney Island, though, while they enjoy the vista, they stay clear of the water.

"We don't try to go in the water," said Joyce. Pointing to remnants of previous visitors -- the trash they left behind -- she asks, "Would you want that in your bathtub?"

While littering can threaten the water quality, the larger danger is the city's combined sewer and stormwater system, which covers about 60 to 65 percent of the whole city. Heavy rainfalls overwhelm the sewage plants and cause untreated sewage and stormwater to run off into our water bodies. More than one-tenth of an inch of rain can cause the sewage system to reach capacity and overflow into the ocean or the Long Island Sound.

"Absolutely, positively, there is no doubt about that," said Councilmember James Gennaro, the chair of the council's Environmental Protection Committee, calling the combined sewer system the biggest threat to our water quality. "This is the gospel."

There have been significant improvements -- in the 1980s the system caught 30 percent of the overflow, while it now contains more than 70 percent. Years ago, it was not uncommon for medical waste or other "objectionable material" to wash up on the beach said Department of Parks and Recreation Deputy Commissioner Liam Kavanagh. Now it is extremely rare that a public beach will be closed because of water quality.

According to a report from the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, which oversees bacteria testing in the city's waterways, the city did not close any beaches due to water quality in 2007, compared to two closures in 2006. It issued 24 wet weather advisories -- pre-emptive warnings to the public to avoid the water after heavy rainfalls -- up from just 3 in 2006. Those warnings come when rainfall is expected to overflow the sewage system. The increase, the report said, is due to a higher frequency of rainstorms.

Compared to the rest of the state, the city's beaches are on the cleaner end of the spectrum -- with Chautaugua County next to Lake Erie exceeding bacteria standards most frequently in 2006, according to a report by the Natural Resources Defense Council. Queens County ranked third best in terms of the number of beaches that never exceeded state standards for bacteria counts. But other parts of the city did not fare as well. In Staten Island, for example, only a third of the beaches never exceeded standards.

At least half of the beach closings statewide in 2006 were attributed to stormwater and sewer overflows, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Testing the Waters

Photo by Olivia Warren

Beaches further from the open ocean generally have higher

bacteria counts and are tested more frequently.

bacteria counts and are tested more frequently.

The city tests most beaches for bacteria once a week, while Rockaway Beach, the public beach with the largest Atlantic Ocean beachfront, is tested only biweekly. Land mass and the body of water contiguous to the beach determines the frequency of testing. For instance, Rockaway Beach consistently averages low bacteria counts -- well within single day and monthly requirements.

On the other hand, private beaches in the Bronx and north shore of Queens, which are farther from the open ocean, have higher levels. According to the health department, there were 50 closure days and 26 pollution advisory days for the city's private beaches in 2007. Douglaston Manor Beach, a private beach nestled in an inlet on the border of Queens, has consistently high bacteria levels. In 2007, the Douglaston beach did not meet bacteria level requirements 81 percent of the time.

Chris Boyd, the director of public health engineering at the city's health department, said Douglaston has been closed since June. Its location, near an area of Queens serviced by septic systems, could affect bacteria levels. "Local residents have reported that they do have some neighbors that have failing septic systems and may be inappropriately discharging them," said Boyd.

The city is currently coordinating a "multi-agency response" to the issues facing Douglaston Beach, said Boyd.

The Limits of Testing

Some advocates contend the testing system does not adequately measure the safety of the city's recreational waterways. Unsafe bacteria levels that result in beach closures are based on 30-day averages, so a single spike will not close a beach. Larry Levine of the Natural Resources Defense Council said the reliance on averages does not reflect current conditions and can be "misleading."

"No one swims in an average water condition," said Levine. "The city needs to do a much better job on an ongoing continuous basis of notifying the public of what the current water quality conditions are."

Boyd disagrees, saying the average monthly testing offers protection to the public since any spike in bacteria would factor into a beach's water quality rating for 30 days. The weekly testing, he added, is also standard.

Some other coastal cities test more often. From Santa Monica to Malibu, beaches in Los Angeles are tested at least several times a week if not on a daily basis, said Dusty Crane, division chief for community marketing service for the county Department of Beaches and Harbors. Her office receives beach quality reports twice a day. Back on the East Coast, coastal waters off Boston are tested once daily with both a top and bottom sample.

Cleaning the Waters

Despite improvements in the sewer system, 27 billion gallons of untreated waste and stormwater still get dumped into our waterways every year. That might stop some New Yorkers from jumping in any urban waves.

The city is implementing several proposals aimed at harnessing more of the overflow. This year, said Gennaro, an underground storage tank in Flushing is being put into use. It could retain 28 million gallons of stormwater that could then be slowly pumped into the treatment system. The $400 million project is meant to alleviate overflow into the Flushing River.

Similar projects have been implemented elsewhere. To protect South Boston's beaches, Massachusetts is constructing a 2.1 mile long storage tank to hold stormwater, according to Ria Convery of the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority.

While separating the sewer system and the stormwater system has become the standard method to address overflow, this would be prohibitively expensive. New York City is testing another, greener approach, said Gennaro. Legislation, which he authored and the council approved this year, requires the city to create a stormwater management plan by December. It likely will include the sprinkling of green roofs and porous pavement throughout the five boroughs.

In addition to that, the Bloomberg administration's PlaNYC 2030 requires that 90 percent of city waterways be clean enough for recreational use by 2030. Some advocates, though, do not think this approach is ambitious enough.

"Thirty years after the Clean Water Act asked for swimable and fishable water, all we're asking for is that you don't get sick if splashed," said Levine. The goal refers to water recreational activities, like kayaking, not swimming.

Floating Debris

At the beach, it's not always just about the water. It's the sand, the volleyball and, of course, the sun.

The health department and parks department both measure beach conditions -- from the cleanliness of bathrooms to the amount of trash littering the sand. (For related story on beach facilities at the best and worst beaches, click here.)

Though it is not uncommon for sunbathers to spot shards of glass or bits of trash, beachgoers across the city say the sanitary conditions have gotten better. Jimmy Cardinoto, 42, has lived on Staten Island for nearly three decades. On a recent morning, he lounged with his two sons on Midland Beach with the Verrazano behind them.

Photo by Courtney Gross

Jimmy Cardinoto with his two sons at South Beach

"The people are starting to care," said Cardinoto. "The trash is there, but it's really not as bad as it used to be."

A beer bottle here. An orange peel there. None of that seems to deter millions from building sandcastles or riding the waves.

"Our biggest challenge is just keeping up with the day to day conditions on the beach," said Kavanagh. "Glass is our number one priority on the beach. People go to the beach to relax, to take off their shoes."

The city has a no-glass policy on its sands, but enforcement presents a challenge. Kavanagh said the parks department is currently working on public awareness and experimenting with new equipment to rid the sands of litter and glass. Since 2002, he added, its beach cleaning fleet has expanded by 32 percent.

According to a report from New Yorkers for Parks, litter was found on 42 percent of city shorelines and broken glass was retrieved on 53 percent of city beaches in 2007. "The largest problem is always the maintenance issue," said Sheelah Feinberg, director of government and external relations for the advocacy group. "That's parks citywide."

In response, Councilmember Joseph Addabbo has introduced legislation to ban the sale of glass containers -- from Coronas to Snapples -- within 150 feet of a beach. A parks department official said it was supportive of the concept, but questioned how it would be enforced.

It takes a lot more than a little litter, though, to deter some New Yorkers.

While setting up a picnic at Manhattan Beach in Brooklyn on a recent afternoon, Debra Void, dressed in a yellow apron, swayed her hips to tunes from a nearby boom box. The 42-year-old's father had already dug into the snacks standing nearby, laid out for the birthday party that was about to ensue.

It was Void's daughter's 19th birthday and the family was at Manhattan Beach in Brooklyn to celebrate -- just like they do every year.

Though the area was crowded, even in the middle of the week, Void, a Starrett City resident, didn't find that surprising. The sun and the surf, after all, always keep her satisfied.

"Good news spreads around," said Void. "This is a place where you'd have a nice time."

When originally published, this article incorrectly stated 14 billion gallons of untreated sewage is dumped in our waterways annually. That figure is actually 27 billion gallons of untreated raw sewage and stormwater runoff.

Â

Mayor Bests the Council in Latest Budget Battles

Photo (cc) Laurence Thurion

The city's $59.2 billion adopted budget for fiscal year 2009, which began July 1, has some winners, but many more losers. The big winners were commercial and residential property owners, who had last year's 7 percent property tax rate cut -- along with the rebate for homeowners -- extended for another year. That is worth over $1.3 billion. The mayor is also a big winner as his use of the $6.5 billion surplus from 2008 all but guarantees an easy budget road over his last 18 months in office.

The most obvious loser in the adopted budget is the City Council. The council got hammered. A year ago there were signs of cooperation between the mayor and council leadership, especially the attempt to avoid the annual "budget dance" in which the mayor cuts favorite council programs, only to restore them during last-minute negotiations. This year, what the council got instead is a budget squeeze.

The council dug itself into a hole by going along with the mayor's use of the 2008 surplus. It failed for the second year in a row to advance a $300 tax rebate for lower-income renters (that would have cost the city about the same as the $400 residential owner rebate, about $250 million).

The council signed off on big service cuts to some of its favorite agencies. Many council members, including Speaker Christine Quinn, expressed regrets about the cut, even though only one member (Charles Barron of Brooklyn) voted against the budget.

Reductions to senior, youth and cultural programs averaged over 10 percent. The biggest cut among those three agencies went to the Department of Youth and Community Development, whose 2009 city funding is $35.2 million less (12.3 percent) than the 2008 city funding adopted a year ago.

The 2009 adopted budget for the Department for the Aging is $15.8 million less than last June's adopted budget for 2008. The Department of Cultural Affairs' 2009 budget is $15.7 million (9.3 percent) less than last year's.

These three agencies, among the few that are primarily funded by city dollars, are natural targets for discretionary cuts, but in the context of the 2008 surplus, the total of $67 million in cuts (representing only 1 percent of the surplus savings) looks both unnecessary and far too severe.

Education, a mayoral priority, fared not much better. As the Independent Budget Office reported in its May analysis of the 2009 executive budget, the mayor cut $324.5 million in 2009 city funding (4.4 percent) from the education budget (after $180.1 million in cuts in 2008). As reported in Gotham Gazette, the council restored $129 million of those cuts, using its own discretionary funds -- a good example of the mayor's ability to squeeze the council. The net result (note that a "cut" is often only a partial reduction of a projected increase) is city education funding of about $7.4 billion in 2009, up 3.0 percent from 2008, but a lot less than anticipated by, say, the Campaign for Fiscal Equity.

Changes Since the Executive Budget

Since he released his executive budget in May, the mayor has had to draw down some dollars from his longer-term budget plan to pay for some new 2008 expenses, such as a contract settlement with police officers. The mayor, though, still looks to be a big political winner in terms of budget management. Absent an economic and fiscal emergency that no fiscal monitor anticipates at the moment, the city's next two fiscal years (2009 and 2010) look quite solid in terms of budget balancing.

In fact, in its May report on the 2009 executive budget, the IBO noted that not only was the 2009 budget balanced, but it also saw the 2010 budget as balanced already. The executive budget projected a 2010 deficit of $1.3 billion, but the IBO estimated that the mayor was underestimating revenues in 2010 by $1.2 billion, thus essentially wiping out the projected 2010 deficit.

The mayor and council through the spring warned of the dangers of an economic downturn, but so far the city has not felt any dire effects. True, budget projections are ever changing, and the adopted budget now anticipates a 2010 budget deficit that is $1 billion higher, at $2.3 billion. But if the IBO revenue projection remains the same, the deficit would then be $1.1 billion, still very manageable at this stage.

The change comes from increased expenses for 2009 of about $600 million, mostly from higher labor costs and last-minute additions to the adopted budget. To pay for that, some $500 million of the 2008 budget surplus originally set for use in 2010 went to balance the 2009 budget. The lost revenue in 2010, plus an increase in projected costs, produces the higher estimated deficit for that year.

Conservative Revenue Projections

The IBO's more optimistic projection of revenues serves as a reminder of how conservative the Bloomberg revenue projections have been over several years. Take the most recent year. A year ago, the adopted budget underestimated actual total revenues for fiscal year 2008 by over $3.8 billion, or 6.4 percent. It underestimated actual city taxes collected by $2.2 billion, or 6.0 percent.

The projections for 2008 were even more divorced from the eventual reality. The budget adopted in June 2006 underestimated actual total revenues in 2008 by nearly $9.2 billion, or 17.1 percent.

Much of the forecasting inaccuracy resulted from economic gains in the city that probably no one could have predicted. The Independent Budget Office, for instance, was closer to actual revenues during those two periods, but not by much. In its May 2007 projection, the IBO underestimated total revenues for 2008 by $3.3 billion, or 5.6 percent. Its May 2006 projection for 2008 total revenues was $7.2 billion under the actual revenues, or 13.0 percent.

Given this recent history, a 2010 budget deficit of $2.3 billion doesn't look tough to deal with. The 2011 and 2012 deficits, projected now at $5.2 billion and $5.1 billion, respectively, are more ominous. (It should be noted that these deficits would pass $6 billion each year if projected $1.3 billion and $1.4 billion property tax rate increases were rescinded.

On the other hand, the IBO May report projected 2011 and 2012 deficits to be much lower, at $3.3 billion and $4.3 billion respectively.

Fiscally Conservative

Low revenue projections played a key role in producing the celebrated, huge surpluses of the past four years. But much less attention has been focused on the expenditure side. It is here that the mayor's conservative budgeting is most evident, especially in its general squeezing of social and human services -- most clearly in the nearly $2 billion cut from agency budgets from January 2008 through June 2009.

First of all, according to the IBO, contrary to his claims, the mayor has increased spending for 2009. The difference in interpretation comes from the way in which the city records pre-payments of future expenses with surplus funds.

But whatever growth there is, very little goes to services. The IBO points out that most of the increase is in debt service and in pensions and fringe benefits for city workers over which the city has "limited near-term control." In most service agencies, spending through 2012 is flat. Education and sanitation are two exceptions.

In spite of the incredibly good fiscal news over the past few years, there have been very few gains for basic human services. Despite the mayor's pledge to reduce poverty, his administration and the council have made little attempt to level the playing field and address income- and tax-burden inequities in the city.

For instance, less than a year ago the New York Times documented the extreme income disparity in New York City. The average household income of the top 20 percent in the Bronx ($108,977), the city's poorest borough, is 18.4 times that of the bottom 20 percent ($5,918). In Manhattan things are even more skewed: The average household income of the top 20 percent ($351,333) is 39.7 times that of the bottom 20 percent ($8,855).

According to the last New York City Housing Survey, median household income for the two thirds of New Yorkers who are renters was $40,000; for the one third who are owners it was $65,000. Yet city tax policy during these boom years has benefited owners, not renters.

And it is not as if federal tax cuts have not already helped wealthier New Yorkers. For example, the most recent impact study of federal tax cuts, a May 13, 2008 study by Citizens for Tax Justice, noted that the top 20 percent of New York taxpayers (statewide) get 96 percent of the benefit from the Bush tax cuts for capital gains and dividends.

Recent budget decisions in New York City - with perhaps the modest (and fading) exception of increased education funding -- have done little to confront the realities of life for millions of New Yorkers. With 18 months to go, the term-limited mayor and council leadership still have some time to re-examine their conservative tax and spending policies.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

Saving Energy, Affordable Housing -- and the Planet

Photo Courtesy of WHEDCo

Building emissions are responsible for the bulk of New York City's total carbon emissions.

The Women's Housing and Economic Development Corporation is demonstrating how

older buildings, such as this 85-year-old affordable housing complex in the Bronx,

could be retrofitted to be more energy efficient.

The Women's Housing and Economic Development Corporation is demonstrating how

older buildings, such as this 85-year-old affordable housing complex in the Bronx,

could be retrofitted to be more energy efficient.

Across the city, tenants are turning off their air conditioners and switching to compact fluorescent lights. Yet even the most energy-conscious renters have no authority to demand changes to inefficient out-dated building systems that are wasteful, costly and polluting. They cannot require their landlords do things like replace old boilers, install Energy Star appliances and low-flow showerheads, or seal walls and roofs that leak air and precious heat in the winter.

The absence of these conservation measures in New York's old buildings drives up costs and enlarges the city's already sizable carbon footprint. Buildings are responsible for nearly 80 percent of New York City's total carbon emissions, significantly more than automobiles. And this city is not alone. Nationally, buildings consume more than 60 percent of the electricity generated and account for at least 35 percent of the carbon dioxide emissions that cause global warming.

The mayor's Office of Long-term Planning and Sustainability has called for fully one third of city's planned carbon reduction by 2030 to come from increasing the energy efficiency of buildings. In this, though, New York faces a unique problem: We have a finite amount of land, and 90 percent of buildings that stand today were constructed well before the availability of new energy efficient technology. This means that reducing building emissions requires retrofitting existing buildings now.

Currently programs exist to help property owners make this kind of investment. Unfortunately, though, there is little incentive for them to take advantage of that help.

Who Pays? Who Saves?

Currently, property owners have little incentive to trim energy costs. New York's Rent Guildelines Board allows owners to pass along building operating expenses to their tenants. This year, based largely on skyrocketing energy costs, it is decidedly more expensive to operate a building than in years past. So, the board, which regulates rents for over 1 million city apartment dwellers, last month enacted the largest increases in nearly two decades.

The rent increases not only placed the financial burden of high utility bills on tenants, most of whom can ill afford them, but also struck another blow to a city rapidly losing affordable rental housing. If public policy simply allows building owners to saddle tenants with increased energy costs, owners have no incentive to do the right thing. Why trade in your SUV if someone else is paying to fill the tank?

Increased energy costs imperil both the affordability of housing and owners' profits. The answer though, is not higher rents, it's lower costs.

The sustainable solution is for property owners to upgrade their buildings and lower their utility bills. It's time to recognize the new reality of high fuel costs and facilitate comprehensive reductions in residential energy use that would save money for owners and tenants alike. Genuinely energy-efficient buildings hold the greatest promise for maintaining housing affordability and profitability, not to mention saving the planet.

Conservation Strategies

The only way to effectively reduce utility-related building expenses is through energy-smart building upgrades. Buildings need efficient heating and ventilation systems; apartments require Energy Star appliances. Building envelopes should be sealed to reduce heat loss in the winter and heat gain in the summer.

Identifying the most cost-effective upgrades requires some engineering calculations, but it is far from rocket science. The analysis and the improvements can be affordable through programs already in existence: in New York State, primarily through the New York Energy Research and Development Authority, or NYSERDA, and via the federally funded Weatherization Assistance Program. These two stable and well-funded programs together amount to Medicare for aging buildings!

NYSERDA, through its Multi-Family Performance Program for existing buildings, provides owners with consulting services and cash incentives to develop an energy reduction plan aimed at reducing energy costs by at least 20 percent. For example, the completion of an acceptable plan in buildings with over 100 apartments triggers an initial $5,000 to $10,000 payment (less for market rate buildings, more for affordable). When the energy plan is 50 percent complete, owners receive from $300 to $800 per unit and, upon completion, another $300 to $400 per unit.

So, if a property owner wants to install a new energy efficient boiler costing $270,000 in an affordable building with 130 apartments, NYSERDA would provide, through these tiered incentives, cash covering between 40 percent and 60 percent of the upfront cost of the boiler, and below market financing for the balance. In this scenario, NYSERDA could pay up to $166,000 and provide financing for remaining $104,000.

Energy consultants estimate that an efficient boiler, correctly sized to heat a 130 unit building and its common areas would save the owner about $29,000 in the first year alone. This translates into a full payback on the owner's $104,000 investment in less than four years. The immediate energy savings, coupled with low financing costs, will provide an owner with ample cash to pay back the loan, while saving energy costs. After the loan is paid off, the owner is left with more savings -- and a vastly less polluting building.

Learning from the Bronx

My organization, WHEDCo, is a nonprofit that owns and develops affordable housing in the Bronx. Nonprofit affordable housing providers have virtually no cushion against rising expenses. Our tenants cannot afford to shoulder increased costs at a time when their wages are stagnating or declining. Energy efficiency for all of us is a matter of survival. So, we are into our second year of a three-year cellar-to-roof energy "retrofit" of our 132 apartment, 10-story, 85-year-old building.

The first year's energy upgrades have already reduced costs for WHEDCo and the tenants by 10 percent. We replaced 132 refrigerators with Energy Star models, installed low-flow showerheads, air-sealed exterior doors and the basement ceiling, upgraded both apartment and building-wide lighting; and weather-stripped entrances. We have fully funded the $167,000 expense for these upgrades through NYSERDA, the Weatherization program, the Deutsche Bank Americas Working Capital Program, Citigroup Partners in Progress and a few foundation grants.