Are Tenants Advocates Out of Leverage?

Photo (cc) Matt Ryan

At midnight on June 15 the state's rent laws, which keep thousands of apartments across the city affordable, will expire.

Tenant advocates didn't want to be here. They put their energy into lobbying the legislature and Gov. Andrew Cuomo to ensure rent regulation would be renewed and strengthened as part of a budget deal. It seemed for a moment that it might work: a property tax cap to get the support of the Republican Senate and a renewal of rent laws for Assembly Democrats. Democratic senators, including Sen. Liz Krueger, said they might not be able to vote for the budget without a renewal of rent laws. Cuomo said a property tax cap and rent laws might both be part of the deal.

But as quickly as hope came, it was gone. The budget was passed, and rent laws had not been renewed.

The fear is not that rent laws will completely expire -- although it is a possibility -- but that the laws will not be strengthened. Instead, advocates fear the laws will be weakened so that more apartments are taken off rent regulated housing rolls.

Now tenant advocates feel they have been left with no bargaining chip and have to hope that Cuomo is committed enough to bolstering the rent regulation. Cuomo has expressed his support for strengthening rent laws, but, like with many of his other policy positions, he has not made it exactly clear what he wants and how he means to get it.

"I think it is up to the governor and what he is going to do," said Michael McKee, treasurer of Tenant's PAC. "He said he supports rent laws, but he hasn't given us any specifics. And he has given away the best leverage we had. I think he is absolutely key -- unless he has a specific plan we are going to wake up on June 16 and we will be screwed."

Lost Hope

McKee has very little reason to be optimistic. The best hope for strengthening rent laws was when Democrats had control of both houses of the legislature.

Thanks to former Sen. Pedro Espada and his position as the chair of the housing committee, advocates saw their efforts to strengthen laws for tenants and to preserve affordable housing die. It wasn't a surprise for them when video was leaked this year showing Joe Strasberg, president of the pro-landlord Rent Stabilization Association, praising Espada.

"The guy who saved this industry was Pedro Espada," said Strasburg in a clip on YouTube, "and everybody makes fun of him because he's in litigation, but if it wasn't for him, this industry would have been hit on all those issues I just rattled off."

McKee wasn't shocked at all by Strasburg's comments. "Espada buried the chance over the last two years of getting stronger rent laws. He had some help, thanks to Carl Kruger and Jeff Klein," he said, adding that he felt Espada was basically "installed" as committee head by the real estate lobby.

And Strasberg's honesty about his relationship with Senate Republicans makes it even harder for McKee to believe that the Democratic majority in the Assembly can get rent laws strengthened without the support of the governor. "It's not that the Democrats are so great," said McKee. "It is that the Republicans are hopeless."

Indebted

"We’re not ashamed of it. We gave and donated and supported all the Republicans,"said Strasberg on the YouTube video. "We basically emptied our piggy bank in order to make sure they capture the Senate. Dean Skelos understands how important we are as an industry -- and it's selfish -- but he understands clearly that if he doesn’t hurt us or he tries to avoid hurting us, we will be there for him next time around, two years from now."

According to McKee, it would be a win for the real estate lobby to have the rent laws re-approved as they are. But he expects Senate Republicans to try to draw the process out until the last minute and try to force the Assembly to accept a bill that actually weakens them.

"We cannot win by pressuring Republican senators. We can't count to 32 in the Senate. I think they will use the classic Republican strategy that Joe Bruno used: let the clock tick, people will get nervous and just before the deadline the Senate will pass a weakened bill, send it to the Assembly and leave town." The only alternative McKee sees to this is for Cuomo to exert his political might and push for a repeal of vacancy decontrol so that rent-controlled apartments aren't taken off the rolls.

Assemblyman Vito Lopez, a supporter of stronger rent laws, says he sees other options. "We have two out of three houses supporting stronger rent laws. We have the first governor to come out strongly for rent regulation and enhancements. Has he been specific? No. But we are in negotiations now on a property tax cap, ethics, and those may be coupled together to work out a compromise."

Some legislators say a push by tenant advocacy groups to include rent regulation in the budget was misguided. Now that the budget is out of the way, they need to redouble their efforts to make sure their concerns are heard while other key issues are being debated.

McKee said that he wants it to be clear to legislators that this is not an issue simply for current tenants; it is also an issue for future generations. "Preserving affordable housing is an issue for the future so that the next generation can afford to live in the city. When we lose an apartment to deregulation it is gone. It's not coming back."

With Housing in Turmoil, Cuomo Offers Few Clues

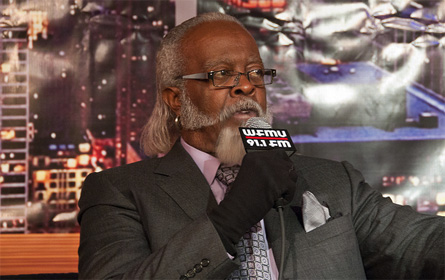

Photo by John Dalton

In his various runs for public office, Jimmy McMillan has famously declared the rent "is too damned high." But, with rent regulation set to expire this year, it could go even higher.

In the days leading up to and immediately following Gov. Andrew Cuomo's inauguration, almost all attention has focused on what Cuomo might do to fix the state's budget woes and clean up Albany. The governor's stands on other issues have received far less scrutiny, and that includes his position on the status of the state's largest affordable housing program -- rent regulation.

2011 will be a big year for New York's tenants, especially for those living in rent- stabilized apartments. On June 15, the state laws governing rent regulations -- which primarily affect New York City -- will expire unless the legislature and governor successfully broker a deal to renew them. Along with limits on some rents, these regulations give tenants the right to renew their leases and protect them against eviction without legal cause, and ensure services.

Cuomo takes office at a particularly turbulent and risky time for housing in the state as New York suffers the fallout from years of predatory lending and the collapse of the housing market. Although Cuomo once served as U.S. housing secretary and has run a housing nonprofit, he has given little indication of what he might do about this crucial issue. The stakes, though, are undeniably high.

Keeping Rents Reasonable

Approximately 1 million apartments in the city fall under the protections of rent stabilization. Another 40,000 city homes are rent-controlled, which is an older -- and some would say more draconian--version of tenant protections. Brooklyn City Councilmember Jumaane Williams, a former tenant organizer, said he is "very worried about the expiration of rent laws. ... I couldn't imagine [the] whole scenario -- I don't know what New York City would look like" without rent regulations in place.

Under the rent stabilization system, the city's Rent Guidelines Board oversees rent adjustments on such apartments. The board itself is a bit of a hot potato as the mayor appoints all nine members without input or approval from the City Council. The Rent Guidelines Board has never not voted in favor of rent increases since its inception in 1980.

Williams said he is "waiting for someone in leadership to really champion the issue …[but I] haven't seen it."

This weekend, rent protection finally seemed to get notice. The Daily News reported that State Assembly Democrats -- the faction in the legislature most supportive of rent regulation -- could demand a strengthening of these protections in return for backing a cap on property taxes, something that Cuomo and many Republican legislators clearly want.

"If we are doing something with real property tax reform, which affects most areas not the City of New York, then the correlating issue for standard of living is affordability of apartments in New York City and that issue should be addressed as well," Assembly Majority Leader Ron Canestrari of Albany told the paper.

Cuomo, though, rejected the link. " My approach is going to be to deal with these individual issues on their own merits," he told reporters. Cuomo has indicated he favors extension of the rent laws, but has not said whether he would support strengthening them or other changes.

Housing in Turmoil

Mario Mazzoni, director at the Metropolitan Council on Housing said, when it comes to housing and tenant issues, the new governor's "platform has been extremely vague and it seems intentionally so. ... It's clearly strategic.”

Many tenant advocates see a need for government to become more actively involved in creating and maintaining affordable housing. The unregulated go-go mentality of the financial world and predatory lending practices during the housing boom have placed rental buildings at risk of foreclosure, leaving many families facing possible eviction or living in apartments where landlords no longer provide essential services.

This "same dilemma" could sooner face middle-income Mitchell Lama rentals, according to Manhattan State Sen. Liz Krueger, although a recent court ruling preserving rent regulation at those apartments may give tenants hope.

Throughout New York City, Krueger said, people who were ill-equipped and "ill-prepared" to own buildings had "fantasies" about making a killing on peoples homes and then bought properties at inflated prices they could not afford. She pointed to the example of Vantage Properties which "went into real estate with a business model, little experience and [the thought they could] increase profits dramatically...by throw[ing] out rent-regulated apartments." Such avarice, the senator said, "fed into predatory lending, which rolled into the economy."

As a result, Cuomo, Krueger said, "inherits an unresolved huge public policy [issue] ... the impact on NYC is literally overwhelming."

Krueger, who was the ranking member of the housing, construction and community development committeeagreed Cuomo "has kept his positions close to the vest. ... I hope he has an aggressive agenda."

She does not necessarily infer anything significant from Cuomo's silence. He has a history of working on housing and homelessness issues, she pointed out.

Cuomo's Record

In 1986 Cuomo created Housing Enterprise for the Less Privileged, now one of the country’s largest builders/operators of affordable housing linked to support services. Connecting support services, such as counseling, with housing as a means to eradicate homelessness was considered groundbreaking at the time.

Cuomo joined the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development in 1992 as an assistant secretary for community development and became HUD secretary in 1996. Cuomo was generally credited with reforming what was once regarded as a grossly mismanaged agency. Overall, Cuomo’s HUD record is considered to be mixed.

Despite this background, advocates find some aspects of Cuomo's track record quite worrisome. Before his election as state attorney general in 2006, Cuomo worked for controversial business/real estate impresario Andrew Farkas and his company, Island Capital Group.

Then there are the massive contributions from the industry to help fund his run for governor. According to the New York Times, real estate interests were Cuomo's biggest donors over the previous three years, accounting for more than 15 percent of what he raised between 2007 and last spring.

Of particular interest is the vast amount donated in 2010 -- more than $150,000 -- by the family of Jerry Speyer, all high-level executives at Tishman-Speyer Properties. Tishman is one of the companies that excessively overpaid and then defaulted on Stuyvesant Town/Peter Cooper Village, the multi-building Manhattan housing complex created in 1943 to provide affordable housing in more than 11,000 once rent-regulated apartments. The complex was turned over to creditors last year. In the process, the fiasco has become the poster child against real estate speculation and predatory lending.

Cuomo, recent articles say, has turned to real estate interests to raise money for a planned public campaign over the budget and against the state's public employee unions. "Business and real estate executives intend to raise $10 million in the coming weeks in support of Gov.-elect Andrew M. Cuomo's looming showdown with government employees unions over wages and pensions," the New York Times reported.

The director and founder of TenantNet, John Fisher, was blunt: "Andrew Cuomo is basically a creature of the real estate industry. ... He's completely bought by developers and landlords."

The Industry's Efforts

Frank Ricci, director of government affairs for the Rent Stabilization Association, a landlord group, agreed it is unclear where Cuomo comes down on housing issues. "It's early," Ricci said.

On its website, the group takes credit for what many tenants consider to be the massive weakening of regulations in 1997. "Our long-term lobbying efforts in the State Legislature and the City Council resulted in the greatest benefits for property owners in the history of rent law negotiations including permanent, realistic vacancy allowances, deposit of rent in court and a strict four year statute of limitations," it reads.

If history can serve as a guide, the real estate industry will spend and lobby lavishly to push its agenda -- including the demise of rent laws. In 2003, Common Cause-NY released Connect the Dots, a report on money in the state's politics. It found, "On top of making large campaign contributions, RSA and REBNY (the Real Estate Board of New York) each have spent over half a million dollars lobbying in the capital since 1999. ... Both organizations consistently report lobbying on rent regulations throughout this period. In total, they spent nearly $1.2 million lobbying in Albany from 1999 to date."

Real estate interests donated approximately a half million dollars to both senate campaign committees of parties between January and July 2010.

Asked about this, Ricci said he would give his customary response to all press inquiries into the matter, that the Rent Stabilization Association has been “meticulous about campaign finance on disclosures."

Over the years, real estate interests been key supporters of Senate Republicans in particular, and the return of the Senate to GOP hands almost certainly bodes well for the real estate industry.

Though there were a few accomplishments -- such as cracking down on illegal hotel conversions and strengthening the rights of regulated tenants whose building is in foreclosure -- during their two years in control of the senate, Democrats disappointed many tenant advocates.

To their dismay, the leadership did not make Krueger head of the housing committee, instead choosing Sen. Pedro Espada who was instrumental in the coup that held up Albany in 2009 . Upon assuming the chair, Espada blocked reforms already passed in the Assembly and introduced legislation many housing activists considered a "Trojan horse," misleadingly friendly to tenants but harmful to them in the long run. Espada, who was defeated for re-election, now faces various criminal and civil charges.

Coincidentally, or not, the Observer has reported, the real estate industry gave $290,000 to the Senate Democratic Campaign Committee in the first half of 2010.

What Cuomo Has Said

In his campaign policy book, Urban Agenda, Cuomo remains silent on rent regulations. The policy book emphasizes the state's need to take advantage of existing federal programs to create affordable housing and spur community development.

It also calls for supporting foreclosure prevention services, and the creation of land banks "to assemble, manage and dispose of vacant land in order to stabilize neighborhoods to encourage re-use or redevelopment of urban property."

Perhaps of the greatest relevance to tenants and owners alike, the Urban Agenda devotes considerable space to the matter of "over-leveraged properties." It calls for the state Mortgage Insurance Fund "to provide credit insurance for refinancing of affordable units" and to work "with bank regulatory agencies to encourage lenders to ...participate in this kind of restructuring process" to save homes and stave off foreclosures.

Beyond that, the book barely discusses the preservation and maintenance of existing affordable homes and says nothing at all about the rent laws, which advocates say are key to keeping affordable apartments affordable. In fact, in his State of the State address last week, Cuomo never discussed the topic though Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver said in his own remarks, “Let us work together to extend and to enhance the protections for these rent-controlled and rent-stabilized apartments so that New York's middle-class families will not find themselves priced out of their homes and communities."

Cuomo’s agenda also does not mention more specific issues regarding rent regulations, many of which have been pending legislation in Albany. That includes repealing vacancy decontrol, which allows landlord to remove some vacant apartment from rent regulations and the Urstadt Law, which bars the city from passing its own, more stringent rent regulations; Major Capital Improvement reform, and an increase in the maximum income tenants can have in order to keep stabilized rents.

Met Council's Mazzoni argued, that given Cuomo's "fiscal conservatism" and emphasis on making government work better for less, he should be at the forefront of strengthening rent laws. "All other affordable housing programs account for barely half the size of rent regulations" which costs the government very little," Mazzoni said. "Ending vacancy decontrol would accomplish more than future constructions of affordable housing."

Cuomo's agenda also omits mention of controversial tax abatement programs that have given developers huge -- though not necessarily permanent -- tax breaks to create small amounts of affordable units. These include the city’s J51 or the state's 421A programs and inclusionary zoning.

These programs do cost the state revenues, which could make them vulnerable in tough fiscal times. That would be fine with some tenant groups.

In a separate email, Mazzoni wrote, "We need to end the so-called affordable housing programs that are geared toward for-profit developers and landlords. It's extremely expensive and inefficient when the cost of running an affordable housing program includes subsidizing landlord profits. It also leaves these assets in the hands of entities whose goals are to maximize profits, not to provide decent housing to people who need it the most -- so they'll always be looking for loopholes to get out of their obligations."

One of Cuomo’s biggest issues during the campaign was to clean up Albany. He stressed that again in his State of the State speech. This could reduce the power of money by establishing public financing of campaigns, establishing low campaign contribution limits for lobbyists and eliminating so-called "pay-to-play" practices.

For Krueger, reform is the key to everything. "The most important is campaign finance, [fighting] abuses, the public interest versus the private interest of lobbyists, who have disproportionate power...[and] say in the legislature and in policy," she said. "I hope Andrew Cuomo is committed to challenging the status quo of lobbyists and funders as the state government."

Jillian Jonas is a freelance journalist focusing on local and national politics, government and public policy. She is a former national political analyst for U.P.I.

Council Approves Safe Housing Act

One of the buildings that made the city's list in 2009.

Taking aim at the city's worst landlords, the City Council expanded a housing program Wednesday that forces property owners to make improvements to the city's most uninhabitable buildings.

The program targets 200 dilapidated apartment buildings a year and requires landlords to address their housing code violations. If they do not fix the problems, the city does it for them and sends them the bill.

Under the expansion, the city will target larger buildings to more than double the number of units under the program. It will also include housing violations directly related to asthma, such as vermin and mold, for the first time.

"Imagine if you were sick and every time you went home it made it worse," said Council Speaker Christine Quinn. "Unfortunately, that is what's happening all over the city."

The bill, Quinn said, would fix that. Dilapidated roofs be gone and say sayonara to some heatless winters.

Despite widespread support for the program, dubbed the Safe Housing Act, it has come under scrutiny since the city failed to capture all of the funds it has invested in improvements from landlords.

Nonetheless, Wednesday's unanimous approval was hailed by tenant and housing advocates, who say the expansion will be a large step toward ridding the city of its most unsafe structures.

"The city will recoup those costs in the future," said Javier Valdes, deputy director for the advocacy group, Make the Road New York. "What's really good for the tenant is that those repairs are done now."

The Expansion

Advocates and residents have horror stories.

Leaky ceilings, mold-infested bedrooms, rats.

Sebastian Riccardi, a staff attorney at the Legal Aid Society, recalled one building that made the city's top 200 in Crown Heights. It had a gaping hole in the roof that was so large someone "nimble" could climb through it, Riccardi said.

To be targeted by the city, these buildings must have the highest ratio of housing violations per unit. Most of them already have tax liens, a city official said. In order to get out of the program, under the initial version of it, all improvements had to be made and all city debt paid.

The initial program, approved in 2007, inadvertently included a disproportionate number of smaller buildings. The expansion will instead target larger buildings.

As a result, the program, which will continue to target only 200 buildings, will go from about 1,000 units to nearly 3,500, said council officials.

In most of the buildings in the program, city officials said, landlords are spurred to make improvements just by landing on the list. But with a third of the owners, who may have abandoned the building, the city is forced to step in to make improvements.

Since the program started, a spokesperson at the Department of Housing Preservation and Development said the city has spent $17 million on improvements to these buildings. It has only received $4.5 million back from landlords.

Arguing in support of the program, officials and advocates say the city will recoup improvement costs plus the cost of any liens on the property eventually.

"It's sort of an investment," said Riccardi.

Over the course of three years, the city has seen only 192 property owners out of 600 graduate from the program. Fiscal year 2010 was the city's worst performing year to date with only 57 buildings exiting the program.

To spur landlords to actually pay back the money, the city's retooled program will include a new payment plan that will enable property owners to pay back the city in installments instead of one lump sum.

Council officials and advocates say the cost of the program will eventually even out. To save tenants' lives, Quinn said, it's well worth it.

"You can't have tenants living in that state of disrepair, while we get the money," said Quinn. "We have to make peoples' conditions livable."

Homeless Cuts Take Aim at Families

Photo (cc)

Christine Nieves clung to a child-sized coat slung over her chest just outside of the Auburn Family Shelter.

It was one of the first December days where a conversation would leave a trail of chilly smoke -- a clear sign winter was approaching. Nieves, 27 years old and Manhattan born, has been calling the city-run Brooklyn shelter home since early summer, she said. Nieves and her three children, two boys, ages 6 and 7, and one girl, 9, have been in and out of the city's shelter system for two years, she estimates.

"There is always a lot of fights in the building," said Nieves. People -- Auburn houses both families and single women -- "bring in drugs, liquor, knives," she added.

Her small children share a "dirty" bathroom with other families.

But for Nieves, things could get worse.

As part of an attempt to close a $3.3 billion budget hole next fiscal year, the Bloomberg administration proposed nearly $1.6 billion in new cuts last month, nearly $19 million of which would strike the Department of Homeless Services over the next 18 months. To close the gap, the department wants to try housing single-parent families with small children in shared "apartment style" units. It plans to scale back the realtor fees for placing homeless families in permanent housing and reduce spending on contracted security at city-run family shelters by 15 percent.

All of this occurs after the city shelter population increased by nearly 9 percent between 2005 and 2010.

"With unprecedented, escalating numbers of homeless families, rising rent burdens along with deepening unemployment and recession incomes -- even growing rent arrears in [New York City Housing Authority] public housing where rents are affordable -- it doesn’t take a policy expert to question the severe cuts proposed for the DHS budget,” said Victor Bach, the director of housing research at the Community Service Society.

With that sentiment in mind, some city officials and advocates are gearing up to strike back. Several officials plan to make fighting the cuts to the city's homeless -- particularly slashes at services for youth and families -- their top priority this budget season, and they are using the mayor's own language as a weapon.

Battle Ahead

In 2005, Mayor Michael Bloomberg pledged he would reduce the homeless population, then at approximately 33,687, by two-thirds by 2009.

The mayor's pledge was punctuated by one of the worst recessions to hit the country in decades, spurring nine rounds of budget cuts, an unemployment rate above 9 percent and a foreclosure crisis that devastated parts of southern Queens and Brooklyn.

The day after Thanksgiving this year, the department had 36,654 people, including 8,259 families with children, in city shelters. The total homeless population using the city shelter system has decreased slightly since last winter -- when it reached a peak of more than 39,000.

While the recession has increased the shelter population, the economy has ripped holes in the city's budget. Despite the circumstances, newly minted Department of Homeless Services Commissioner Seth Diamond remains confident he can continue to fulfill the mayor's campaign promise.

"We are very aggressively working to reduce the population," Diamond told Gotham Gazette last week. "The overall census is down 5 percent in the past year."

"We are [reducing the budget] in a way that we think is creative," the commissioner explained.

One of those innovative methods, Diamond contends, would be to test putting different families with single mothers and children under five in the same unit. Diamond said each family would still have its own bedroom but would share a kitchen and bathroom. He argued the living situation would provide comfort and stability for families who can rely on each other for support.

Those in and out of the shelter system do not see it that way.

"I don't want to share rooms with anyone else," said Nieves back at the Auburn Family Shelter.

"Why would I want another family with me?" asked another woman at Auburn, who did not want her name used, as she walked her daughter to school.

Patrick Markee of the advocacy group Coalition for the Homeless said the city had adopted a similar policy in the 1980s. But the City Council eventually banned it.

"When the city used to shelter homeless families in doubled up arrangements, there were all sorts of problems: Children and adults getting sick, children going to the bathroom in tin cans because they are afraid," said Markee. "The City Council passed the law in the '90s to move away from those terrible and unhealthy conditions."

In order for the administration to test the plan, which the department would like to do at eight facilities with the potential of adding between 5 and 40 units per facility, the City Council would have to officially revise the law. Already, the department has an uphill battle.

“The law in question is in place to protect the health and safety of our city’s homeless families and children," said Councilmember Annabel Palma, the chair of the council's General Welfare Committee. "I do not want to see us, as a city, move in the wrong direction and roll back hard won reforms.”

Council Speaker Christine Quinn's office said the council would review the proposal, which would take effect during the next fiscal year, at the "appropriate time."

Keeping Services Up?

Beyond doubling up, the department plans to reduce broker fees from 15 percent to 12 percent for those who find housing for homeless families. Advocates question whether the reduction would provide less of an incentive for realtors to find homeless families permanent housing.

It also plans to provide a financial incentive for shelter providers to move families into permanent housing at a faster pace. Currently, providers start receiving a lower rate of pay after a family has been there for six months. To save money, the department will begin reducing pay after five months.

Several shelter providers refused to be interviewed for this story, fearing fallout from the department. Some did confirm to Gotham Gazette their overall concern for how these cuts would affect getting services, especially for families.

Shelter Safety

The department will cut its contracted security at the four family shelters it directly runs, like Auburn, by 15 percent.

According to the latest data from the Mayor's Office of Operations, critical incidents at family shelters have gone up 250 percent this fiscal year. Diamond attributed the increase to an expansion in the definition of "incidents" to include domestic violence.

"We are reducing [security] from a very high level to a high level," Diamond said. "At the end of the day, we still have to have safe and secure facilities."

Diamond's determination to keep services the same has not quelled concern among those using those services, like Chanel Daugherty.

The 32-year-old woman, who has seven children between the ages of 3 and 9, lost her home on Staten Island after a fire. Now she is at Auburn and is waiting to get a permanent placement from the city elsewhere.

She called the conditions inside the shelter system "terrible." The lack of heat leaves her kids shivering all night.

"I hope a change comes about," Daugherty said.

Homeless Youth

The homeless have taken hits outside of this department's budget.

Drawing the ire of advocates and officials, the Department of Youth and Community Development has proposed to eliminate all of its funding for outreach for homeless and runaway youth and reduce funding to its five youth drop-in centers. The total cut in fiscal year 2011 would be $569,000.

The city's loudest opponent of the proposal, Councilmember Lew Fidler, says it is downright hypocrisy.

"A lot of these 3,800 kids that are on our streets every night aren’t looking to be helped," said Fidler. "Someone has to be looking for them."

Several weeks before the citywide election last year, the mayor announced a commission to study lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender runaway youth. The report came out this summer, Fidler said, and called for more shelter beds.

Now, Fidler said, they are cutting instead.

"Happy holidays, merry Christmas," Fidler said. "What could be crueler?"

In response, a spokesperson from the Department of Youth and Community Development argued that, up until now, funding for runaway and homeless youth has been spared.

"Due to a combination of city and state reductions for fiscal year 2011 and fiscal year 2012, [the department] has made the difficult decision to reduce runaway and homeless youth services funding," said Andrew Doba, the department's spokesperson. "This reduction was proportionally less then other reductions in the [the department] portfolio."

Unlike the Department of Homeless Services proposal to double of families, this cut may not need City Council approval. In between fiscal years, the mayor can direct agencies to cut spending. Only new appropriations need council approval.

Nonetheless, the council kicks off its budget hearings on the entire mid-year plan today.

Council to Expand Safe Housing Act

Photo (cc) 2010 Courtney Gross. HPD Commissioner Rafael Cestero, Council Speaker Christine Quinn and Councilmember Gale Brewer announce new legislation Tuesday.

Clutching a sign splashed with the slogan, "No More Asthma," Rodrigo Castillo relayed the saga of living in a dilapidated, practically abandoned apartment building in Sunset Park.

From the steps of City Hall on Tuesday, Castillo described through an interpreter the winter he spent without heat or hot water and the endless trail of rats and cockroaches permeating his place.

He also described his 11-year-old son, Nicholas, whose asthma continues to get "worse and worse and worse."

Nonetheless, Castillo's landlord has done nothing in response.

But thanks to a retooled city program, Castillo and more like him can get help, City Council officials said. Council Speaker Christine Quinn announced Tuesday the expansion of the Safe Housing Act, originally approved in 2007 to target 200 buildings with the worst housing violations for improvements. As part of the expansion, the council will consider legislation to isolate larger buildings and properties with violations connected to high asthma rates, like mold and vermin infestations.

Quinn said the proposal's approval would eventually curtail emergency room visits in neighborhoods saturated with dilapidated and distressed residences.

"We are recognizing that peoples' homes can actually make them sick," said Quinn. "Asthma has a tremendous amount to do with housing."

Keeping Housing Safe

When first approved, the program captured more than 1,000 units in 200 buildings per year. Under the expansion, the program will continue to target 200 buildings per year, but it will aim for larger ones. The council estimates the expansion will more than double the number of apartments covered by the program, climbing to as many as 3,000.

The latest iteration (Intro 436) of the Safe Housing Act is part of a focused enforcement effort by the city to pour inspectors into buildings with the most hazardous violations. Under the effort, if a landlord refuses to make repairs to bring a building up to code, the city makes the improvements for them. The city then sends the property owner the bill.

Housing Preservation and Development Commissioner Rafael Cestero estimates two-thirds of landlords make the repairs on their own.

Under the new proposal, buildings with less than 20 units could be targeted if they have more than five immediately hazardous violations, like mold, per unit for the preceding two years. If a building has more than 20 apartments, each one would have to have approximately three hazardous violations to qualify. The legislation also could impact buildings with liens for emergency repair charges from the city.

The latest expansion, Quinn said, would not bear any substantial additional cost to the city.

When announcing the expansion Tuesday, a swarm of advocates and residents cheered on the council from the steps of City Hall. They claimed the bill would save lives.

"With the expansion of the Safe Housing Act, we can learn how to more effectively address pest and mold violations that negatively impact the health of thousands of asthmatic New Yorkers, and ultimately improve the quality of life for those children and families," said Michelle de la Uz, the executive director of the Fifth Avenue Committee, an advocacy group in South Brooklyn.

Quinn said the council would hold a hearing on the bill on Dec. 14, and it would be approved shortly thereafter.

Traffic Calming Transparency

As fierce controversy over the increase of bike lanes heats up, the City Council approved legislation Tuesday to force the Department of Transportation to map out criteria for the construction of certain traffic calming devices, including speed bumps and bike lanes.

The bill, (Intro 376) which was approved unanimously, will reveal to the public the logic behind installing traffic calming measures, from median islands to curb extensions, council officials said. Councilmember Jimmy Vacca, the bill's chief sponsor, said it would also provide a check on the administration to ensure these measures are being approved or rejected appropriately.

"It means people are going to have the power to advocate for themselves," said Vacca.

The bill would not list reasons for each individual installation, but would provide a broad definition of why one measure goes in a certain kind of traffic area. Vacca said when the legislation goes into effect, community members will know why a lane goes on one street and not another.

The bill would only apply to bike lanes used as traffic calming measures, not lanes that are installed to connect to other bike lanes.

But in this transportation climate, some questioned whether the bill could be used as a weapon against bike lane expansion.

Vacca said the bill was not "anti-bike."

Job Creation Requirements

Also on Tuesday, the council unanimously approved legislation (Intro 256) to require the Economic Development Corp. provide more information on the lease and sale of city-owned property.

The corporation will have to release an annual list of each lease the city has, the rent it receives from each property and the conditions of any property's sale.

Under the legislation, which was passed unanimously, the corporation will also have to create a database, which includes all job creation information for city-subsidized projects.

Creating Affordable Housing: How Koch Did It

Photo by Anthony Catalano

In his third and last term, Mayor Ed Koch, shown here at a parade in Brooklyn in the mid 1980s, focused on finding ways to build affordable -- but not necessarily low-income -- housing in the city.

In 2002, Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced a plan to increase affordable housing in the city, a plan that, whatever its success, has become a hallmark of his administration. In embarking on the project, Bloomberg was taking a page from one of his predecessors, Ed Koch. As New York emerged from the fiscal crisis in the 1980s, it faced a shortage of housing. Koch set out to address that, using new strategies and innovative financing.

This excerpt from the new book, Ed Koch and the Rebuilding of New York City, by Jonathan Soffer (Columbia University Press), explores the thinking behind the Koch housing plan, the obstacles it encountered and the successes that made Bloomberg look to it as a model some 15 years later.

In his 1985 State of the City message, Mayor Edward I. Koch announced the most ambitious plan of his political career: a five-year $4.4 billion city-financed program to build and rehabilitate 100,000 low and moderate-income housing units. The idea took off, and several weeks later he more than doubled that goal, expanding it to 252,000 units, with a revamped 10-year plan, revised once again in 1989, that committed $5.1 billion to finish building the units by 1996.

It was an extremely risky move. At first, no one in his administration knew exactly where the money would come from. But Koch and his aides managed to pull much of it off, and the housing plan became his most enduring achievement.

The plan began modestly enough during a lunch of senior administration officials. Abraham Biderman, then a housing adviser to the mayor who later served as housing commissioner, recalled that they sketched out the first draft of one of the largest housing investments in New York's history on the back of a napkin.

The Housing Crunch

They realized that New York was facing an affordable housing crisis. Between 1978 and 1981, the number of apartments renting for $200 a month declined by 43 percent, with 67 percent of renters spending more than 35 percent of their income on rent. And in Koch's first term, 81,000 units of housing, mostly at the lower end of the scale, disappeared.

"At that time, the city population was growing, the jobs were growing, but there was no housing being created for all sorts of reasons, and this was the critical linchpin to the whole city economy," Biderman recalled.

The New York Way

The new housing program was very much in the tradition of the public agencies, workers cooperatives and public-private partnerships that had been building housing for low- and middle-income people in New York since the 1920s. The most unprecedented element of the Koch plan was that, while it would be financed with cross subsidies from luxury projects, and from state entities such as the Battery Park City Authority, the bulk of the money would come from the city's capital budget.

Public housing had a bad name in many parts of the country because it was often badly managed by political hacks, and it was seen as a dumping ground for the poorest of the poor. But 20th century New York had a long tradition of public housing that was well maintained by civil servants. The Housing Authority continued to provide quality housing, even during the fiscal crisis, when money for maintenance was increasingly hard to come by.

But Koch had little interest in building new high-rise projects. Housing officials understood that one reason for the relative success of New York's public housing was adequate expenditures on maintenance, and they were loath to undertake any housing project that would permanently increase the expense budget. So while the Koch plan was generous with capital funds, officials hoped that private and nonprofit ownership would shift most maintenance expenses to private owners. The city also aided this goal with tax subsidies designed to subsidize maintenance and improvements.

Putting Meat on the Bones

The scale and complexity of the various programs that made up the Koch housing initiative were breathtaking. The plan had four main goals: gut renovations of all suitable city-owned vacant buildings; moderate renovation of all occupied city-owned buildings; promotion of below-market-rate loans and tax breaks to encourage owners of low and middle-income housing to renovate; construction of new homes for owner-occupants. The units would be located all over the city but concentrated in the South Bronx, Harlem and central Brooklyn.

In New York, supporting affordable housing is, in theory, as safe an issue as opposing littering. In practice, the mayor got flak for his program from both the left and the right. The right wanted an unregulated private housing market, arguing that market forces would lead to construction of more affordable housing.

At the same time, Koch's housing program came under fire from housing advocates on the left who had become more concerned about redistribution and homelessness than about class and racial integration. They deplored Koch's decision to build significant amounts of middle-income housing, demanding that the needs of the poor come first. Bonnie Brower, the executive director of the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development, argued that the Koch housing program did not sufficiently address the needs of low-income households. "If they want to build middle-income and upper middle-income housing, let them at least call it by its right name, and let us deal with it on its merits," Brower commented.

The Koch housing program, though, was primarily an economic development program, not a welfare program. Koch aimed to rebuild areas devastated by abandonment and neglect into neighborhoods that were viable and self-sustaining without continuing cash subsidies or maintenance expense that would have to be paid from the expense budget. Deputy Mayor Stan Brezenoff wrote, "We cannot preserve the city's long-term health if we do not address the needs of the middle class by putting public resources into creating housing for this group. If we don’t, who will be here to fill the jobs and pay the taxes that support services and housing creation for the poor?"

Low-income subsidy projects cost more, which meant fewer renovations could be undertaken with the funding available, leaving more holes in the fabric of neighborhoods. An program relying entirely on subsidies also would tend to create ghettos of low-income families who had the least social stability, a particularly questionable idea in 1986 at the height of the crack epidemic.

Housing commissioner Paul Crotty was impatient with complaints from "ideologues and advocates" that most of the housing was aimed at middle-income residents who could afford to buy housing in the $25,000 to $40,000 range or pay equivalent rent in proportion to their income. He kept telling them, "Not every program can meet all the income targets There's lots of notes on this organ; you have to hit all the notes."

Repopulating New York

Such a complicated set of programs, with so many sources of funding, posed daunting obstacles to construction. "The hardest thing to get built is housing," a frustrated Koch told the press after a year and a half of trying to cajole the bureaucracy into building buildings. Complicated financing and regulation, the impact of scandals, and the need to create effective bureaucratic channels between a hodgepodge of agencies all militated against his will to build.

Until the mid-1980s, New York's housing stock did not grow significantly. In 1983, for example, the addition of 11,251 newly built or renovated units was offset by the loss of 11,133 units through demolition and conversion to nonresidential uses -- a net gain of only 118.

Nonetheless the Koch administration policies and an improving economy began to turn the shrinking city into a growing one. Once the recession ended in 1984, losses of housing slowed to a trickle, and the combination of private and public construction led to a net gain of 37,000 units by 1987, boosting public confidence in Koch's new expanded housing program.

After 1986, there was much more local control over the kinds of projects that were built, because the housing initiative was using mostly city and state money. Local control and the continuing destabilization of neighborhoods had made construction of affordable housing popular again.

The program shifted the goals for government housing programs from a welfare model primarily interested in housing the poorest to a more racially and income diverse affordable housing model, presaging a similar shift in public housing projects (as Nicholas Dagen Bloom points out in his book Public Housing That Worked). "We definitely wanted to have a mix. ... It's a combination that we strove for, including the working poor and a little bit of the middle class," Biderman recalled.

Finding the Funds

Cobbling together the complicated financial package to do this took significant politicking at the state level. Most of the money came from the city's capital budget, after the legislature freed up billions in borrowing capacity by creating a separate Municipal Water Finance Authority for the enormous third water tunnel project. More money came from various state agencies that had surpluses or that owed the city money, including the refinancing of Municipal Assistance Corp. (MAC) bonds, a $200 million payment in lieu of taxes from the World Trade Center (less than Koch had hoped), $3.2 billion in increased borrowing by the Housing Development Corp. and approximately $400 million from the Battery Park City Authority, which was borrowing against anticipated funding from the World Financial Center. Interestingly Koch saw the transfer of Battery Park City Authority Funds to low-income housing as a way to justify state subsidies for a luxury downtown development.

Progress was slow for the first two years following the initial announcement of the housing program in January1985. The fallout from the Parking Violation Bureau scandal of 1986 made the task of creating new shortcuts around bureaucracy even tougher. Auditors and prosecutors monitored every city transaction, subpoenas disrupted the normal work of agencies, and anti-corruption procedures increased paperwork in a system that was already drowning in it.

By the end of 1987, the city had managed to increase both direct and indirect capital budget support for housing, though turning that money into occupied units was more difficult than Crotty had anticipated. Almost immediately, the transportation department was able to start upgrading streets and infrastructure near affordable housing project sites. The greatest holdups were the bureaucratic hurdles involved in disposing of city property. The housing commission could provide city-owned land for only about 3,000 new units.

The Reagan administration, which by 1984 had cut federal budgetary authority for housing to one third of its 1980 levels, actively disliked government housing construction programs. Reductions in federal aid to cities began under the Carter administration, but conservatives hastened the process. Federally funded gut rehabs and new housing starts in New York City plunged from 6,500 in 1983 to fewer than 500 by 1988. The only assistance Washington offered Crotty was the badly conceived and ideologically driven voucher program.

What They Built

The public-private hybrids that actually constructed much of the housing under the plan did not always work smoothly. Some were disasters, such as Tibbets Gardens, the failed four-year effort with the Real Estate Board of New York to build housing in the Kingsbridge neighborhood of the Bronx. The Manhattan real estate professionals were used to working on a large scale and "just couldn't adapt their overhead and their whole method of operation, including the nature of the subcontractors that they used and the cost of those subcontractors, to the environments that we were working in," Biderman explained.

Others flourished. From the Mid-Bronx Desperadoes to the well-heeled Rockefeller-sponsored Housing Partnership, nonprofits managed to transform the streets of once decimated neighborhoods. Andrew Cuomo's Project Help, which built transitional and permanent housing for homeless families, was one of the most successful, in part because it benefited from the generous funding that the son of a sitting governor was able to obtain. Despite the difficulties and delays, Koch's program of decentralized public investment stimulated private developers in the Bronx to build new structures on undeveloped land within a few months of this initial announcement.

City projects also improved in quality during Koch's third term. Deputy Mayor Robert Esnard, an architect by profession, believed that aesthetic appeal and amenities were key to successful public housing construction, even for the homeless. He convinced the prominent architecture firm, Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill, to design apartment blocks that each contained 24 units of transitional housing for homeless families, with counseling and recreation facilities on the first floor and the apartments above. The first one, an unobtrusive three-story hundred-unit building at 346 Powers Ave in the Bronx, was completed in 1990, with 10 more sites under construction or approved by the Board of Estimate. The firm earned nothing for the design itself.

New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger described a prototype as "an impressive building, at once sensible and humane," noting particularly the apartment design of "eight single rooms around double-height living rooms."

The housing commission's programs did more for homeless families than single adults, who needed more intensive social services. In a 1992 interview, Biderman said, "We almost came to the point where we eliminated the [welfare] hotels [as temporary housing for homeless families] altogether but unfortunately, since then, they have begun to grow again."

Red Tape

Housing advocate Kathryn Wylde [now president of the Partnership for New York City, a business group] chafed at the relatively slow pace of construction, especially during those first two years. Wylde argued that New York's bureaucratic delays and paperwork made the cost of delivering a manufactured house to moderate-income buyers in New York 30 percent higher than for the same house in New Jersey. But the Koch administration argued that progress was remarkable given the slow paper flow through primitively computerized agencies, the distraction of subpoenas and the proliferating new safeguards against corruption.

Koch and Crotty began to take Wylde's complaints more seriously when the Daily News in an editorial probably inspired by Wylde, described the "nightmarish" and "Kafkaesque" bureaucracy required to build new housing in New York City. To drive home the point, the News illustrated its editorial with a diagram of 35 pieces of paperwork required to complete an apartment rehab, nothing that "printing the diagram for a major project -- say, a new apartment house -- would require a Playboy-style centerfold." Crotty challenged the accuracy of the diagram, which, he said, "confused the approval process with the construction process."

Still, bureaucratic absurdities abounded. "Different agencies didn’t want to be pushed into different things ... so we were always in a state of mini-war with agencies," Biderman remembered.

Financing sometimes failed to materialize, and in July 1986, when Koch and Crotty announced the second phase of the MAC housing plan, it came out at the press conference that only one 16-until building on Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn had been completed under the first phase, with a second building underway on Staten Island. Instead of the 800 units for $20 million first contemplated for phase one, the project had been scaled back to 450 units with a budget of $15 million.

One area that scared the bureaucrats was the innovation of public-private partnership, which sometimes crossed then-sacred legal boundaries between public and private. Deputy housing commissioner Charles Reiss, speaking at a 1984 conference, called the Housing Partnership's New Homes program "the hardest and most difficult to get going, and to follow through to construction and occupancy" of all the city's housing ventures.

City bureaucracies were woefully limited by rudimentary computers. In an age with only primitive word processors, Reiss cited as the primary obstacles to housing construction the glacial production of legal papers, a process that "seemed to take longer than the actual construction of the houses." Reiss also feared that housing built on vacant city land in bad neighborhoods might not be marketable, creating a huge budgetary scandal.

The 1986 city corruption scandals made it harder to give away city property for fear of impropriety, even for the laudable purpose of building affordable housing. The administration responded by setting up a high-level committee under Esnard to value the land for each project. Housing activists and developers complained that the committee greatly increased their paperwork, but such painstaking preparation in the first two years of the housing initiative paid off.

"This was one of the major public works programs, which was never tainted by scandal, kickbacks, shoddy work. And to get that done we had to have all the right systems in place. And it took time. But once they were in place, it definitely began to move," according to Biderman.

By fiscal year 1988, the pace of construction began to pick up. Housing completions went from 12,763 in FY1987 to 15,388, a 17 percent increase and the most since 1976, with nearly two third of the units in the outer boroughs. Between FY 1987 and FY 1990, annual expenditures under the hosing program went from $62 million to $340 million.

In the early 1980s, Koch was widely mocked for putting window detail of Venetian blinds and potted plans on abandoned buildings overlooking the Cross-Bronx Expressway in a vain attempt to make them look better. By the 1989 mayoral campaign, Koch was able to break ground on a project to renovate those same buildings, and the mayor traveled to the Bronx to remove the first decal himself. By the time Koch left office the following January, the housing program alone had renovated 3,000 apartments, with 13,000 more under construction and design work started on an additional 20,000.

"My plea is to the next mayor: Don’t undo the housing efforts of the Koch administration," wrote Willa Appel, executive director of the Citizen Housing and Planning Council shortly after Koch's defeat in 1989. The Dinkins and Giuliani administrations continued to build housing under Koch's 10-year plan, using the bureaucratic pathways he had bushwhacked, though Dinkins increased the subsidies and numbers of apartments built for the poorest families. Giuliani eventually decreased annual capital expenditures to $235 million in 1998, about one third of what Koch had spent at the program's peak. In the previous 10 years, New York spent a total of $4.4 billion on the housing program -- a step forward but less than needed.

More than two decades after the program was announced, Koch's initiative has generally been viewed as the greatest success of his 12-year mayoralty. The housing he built did not end homelessness but did help rescue New York. Vacant abandoned houses are no longer a common sight, and the value of homes in the city remained more stable than in most other areas of the United States during the general housing contraction that began in 2007.

In total, between 1987 and 1993, more than 100,000 units were renovated or constructed, Overall, however, the cost of housing in the city remained high and would continue to increase, in part because the population increased from 7.5 million in the Koch years to more than 8 million in 2008.

In 1998, Bronx Borough President Fernando Ferrer invited Koch to the Bronx to see the fruits of his success. Times reporter David Gonzalez was present and rhapsodized that as a result of Koch's 1-year housing plan, "entire blocks have come buzzing back, with children and families living in new townhouses and renovated apartment buildings."

Koch has frequently been criticized, sometimes with justification, for being a crisis-oriented mayor -- governing through short-term responses to the headlines. But his major strategic decisions -- the restoration of New York City's credit and the 10-year housing plan -- were exceptions that put the city on an upward curve for the next generation.

Jonathan Soffer is an associate professor of history ay New York University's Polytechnic Institute, specializing in 20th century American and urban history.

Excerpted from "Ed Koch and the Rebuilding of New York City" by Jonathan Soffer. Copyright © 2010 Jonathan Soffer. Used by arrangement with Columbia University Press. All rights reserved.

Now Obama Seeks to End Homelessness

Photo by Paradiso 76

Upon taking office in early 2009, President Barack Obama said ending the "national disgrace" of homelessness would be a priority. In June, the Obama administration unveiled Opening Doors: Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness, an ambitious commitment by the federal government to end veteran and chronic homelessness within five years, and to eliminate homelessness for families within ten.

Many homeless activists consider this commitment to be groundbreaking because it is comprehensive, establishes a time frame, and is quantifiable. Patrick Markee, senior policy analyst for the Coalition for the Homeless, called it a "landmark" for the president to address homelessness so extensively and "important historically. ... After 30 years of modern homelessness, [you] can't underestimate the significance."

The plan's effect on New York City remains uncertain. The key overall, though -- in New York and elsewhere -- will be whether the administration can accomplish its goals. In 2004, Mayor Michael Bloomberg adopted his own 10-year plan to sharply reduce, if not eliminate, homelessness in New York City. The goal has fallen far short of its goals. Instead, during his tenure, homelessness has increased and by some measures, it is at its highest level ever, according to an analysis by the Coalition for the Homeless. A record 120,381 different homeless men, women, and children slept in New York City municipal shelters at some point during fiscal year 2009.

Many Fronts, Many Players

The Obama administration says its efforts have already had an impact. It reports the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, popularly known as the stimulus plan, has helped prevent homelessness for more than 350,000 people in its first year alone.

But on any given day, approximately 640,000 men, women and children, including 107,000 veterans, find themselves homeless in the U.S. According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, about 1.5 million people were homeless at some point during 2009. In New York City, the Department of Homeless Services reports more than 35,000 people, including children, currently live in shelters. The Coalition for the Homeless calculated this as the highest level since the Great Depression.

The federal plan was devised by the U.S. Inter-Agency Council on Homelessness consisting of 19 different federal agencies including the departments of labor, housing, transportation and human services. Their task was to create a far-reaching strategy that would expand and better coordinate the fight against homelessness by all levels of government along with nonprofits, religious institutions and other providers. The strategy aims to make this effort more efficient and effective, and has incorporated feedback from many providers and homeless advocates -- the people in the trenches.

It expands the policy adopted by the Bush administration, which concentrated on the chronically homeless, considered to be the most difficult population to help. Also, Bush’s plan emphasized having localities create their own plans; Obama's emphasizes the federal government's role in coordinating these efforts.</>

The inter-agency council is chaired by Housing and Urban Development secretary Shaun Donovan, a former commissioner of the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development.

"As the most far-reaching and ambitious plan to end homelessness in our history, this plan will both strengthen existing programs and forge new partnerships. ... We will harness public and private resources to build on the innovations that have been demonstrated at the local level nationwide. No one should be without a safe, stable place to call home,” Donovan said Donovan in a press release.

The First Steps

The 74-page plan emphasizes the need for stable and affordable housing, and federal housing assistance. While it does not cut existing programs, it also does not increase funding. There are currently 13 different rental assistance programs available through Housing and Urban Development, and approximately 3,000 different public housing authorities across the country.

The plan highlights the shortage of affordable housing, a particular concern to New Yorkers. "A January 2010 review of characteristics of U.S. rental housing found that from 2001 to 2007 the nation’s affordable unassisted rental housing stock decreased by 6.3 percent, while the high-rent rental housing stock increased 94.3 percent. This translates into a loss of more than 1.2 million affordable unassisted rental units from 2001 to 2007," it says.

While specific guidelines are still being written, Sam Miller, a housing coordinator with the Housing and Urban Development's New York Regional Office, described the strategy as a "consortium continuum of care" that is "homeless-centric."

The plan offers 10 objectives and 52 strategies. Some are merely proposals or ideas while others are already in place and working. Highlights include:

--rapid rehousing initiatives that skip shelters and instead place homeless people directly into permanent housing;

--more supportive housing, which offers people not only a place to live but also social services, employment help and the like;

--funding for the National Housing Trust, which preserves and restores affordable apartments;

--linking federal housing vouchers with health and social services provided through Medicaid and multi-faceted services funded through the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families program, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and other agencies;

--outreach to families through a network of emergency domestic violence shelters;

-- grants administered by the Department of Labor to provide homeless veterans with skills training, job search assistance, placement, and other services, including an initiative targeted at homeless female veterans.

In addition, the administration is counting on the Affordable Care Act, the recently passed healthcare legislation, to permit homeless people or people most at risk of homelessness who now have no health coverage to be eligible for Medicaid in 2014, thus removing the economic hardship posed by a catastrophic illness.

Targeting the Help

The strategy distinguishes between homeless sub-populations: the chronically homeless, veterans, families with children, and youth, including lesbian, gay, transgender and bisexual people. There is some indication between 20 and 40 percent of all homeless youth identity with this group and are forced to leave home because of their sexual orientation.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development also has expanded its definition of who is homeless beyond just people living on the streets to include people such as those living in shelters and those doubling-up in homes with friends or family because they can’t afford their own place.

Not every homeless advocate applauds the idea of categories. Neil Donovan (no relation to Shaun Donovan), executive director of the-D.C.-based National Coalition for the Homeless (on whose board Markee sits) said it is important to "address the total [homeless] population, not one part at a time." Breaking people into groups, he continued, means there will inevitably be "weak links ... and a disproportionate amount of resources" could be allocated to the sub-populations that may not need the most assistance.

In addition, Neil Donovan worries that the "actual chronic rate of homelessness is higher" than what is reported because providers tend to gravitate toward helping the population that receives the most government and private money. Donovan believes the way assumptions and measures are currently proposed is likely to establish a "hierarchy of less deserving or undeserving." Moreover, he has issues with the plan's lack of specificity and its "patchwork of solutions."

Homelessness and Poverty

"Opening Doors" was released at an opportune moment, with homelessness and poverty at record highs due to a myriad of factors including the recession and subsequent job layoffs and foreclosures; stagnating wages, and the cost of health care. Violence against the homeless has also reached record highs.

Newly released data from the U.S. Census Bureau reports 4 million Americans fell below the poverty line in 2009, while one in four African Americans and one in five American children lived in poverty. Data for New York City revealed more people living below the poverty line in 2008 than did nationally, 13.7 vs. 13.2 percent respectively. More than one fifth of all New York City residents -- 21.3 percent -- had incomes below the poverty level in 2009, according to an analysis by the Fiscal Policy Institute. Nearly half of those people had incomes equal to less than a half the poverty threshold -- or less than $10,500 for a family of four.

Echoing the City?

Despite the obvious need for services here, in practical terms, the city may not realize any substantive change in homeless services, explained the coalition’s Markee. "The federal government’s role has been smaller in New York City than anywhere else. So we’re not as reliant as other local and state governments. We [are not] waiting for the feds," he said.

Regardless, the commissioner of the city Department of Homeless Services, Seth Diamond, said he was pleased with the president's plan, and that the city had been "consulted" in its creation. He was especially encouraged that "Opening Doors" includes the strong emphasis on prevention that has characterized the city's efforts for years. It shows, Diamond said, "the city has been out front" in the struggle to end homelessness." The federal plan, according to Diamond, would take up many of the efforts the city already has undertaken, such as employment services, rehabilitation and partnerships with community-based providers.

Even though "Opening Doors" does not discuss additional funding for the program or for New York City, Diamond sees it as a “first step, the initial effort ... [that homelessness] is an important priority” for the administration. "Additional funds and funding reallocation may come next," Diamond said. And the plan may also enable help homeless people tap into other, existing sources of funding they may not have taken advantage of, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

New York, according to an email from a city official, already "does an excellent job at linking homeless individuals with TANF support and services. We are a location that is very strong in this area."

"The biggest obstacles" to fighting homelessness in New York City, Markee said, is the Bloomberg administration's policy to deny federal Section 8 housing vouchers to the homeless. Before then, he said, "every other mayor ... had allotted some [vouchers], ranging from 1,500 to more than 4,000, resulting in [about] 1,000 to 2,000 apartments to homeless families." What’s worse, according to Markee, is that "no other city has ever denied all of its vouchers to the homeless.

The Section 8 housing voucher plan is the Department of Housing and Urban Development's largest rental subsidy program. "Currently homeless families in New York City have virtually no access to the two major federal housing programs available to low-income households: the Housing Choice Voucher program (also known as Section 8 vouchers), and public housing (administered by the New York City Housing Authority)," the coalition said in testimony to the State Senate.

Jillian Jonas is a freelance journalist focusing on local and national politics, government and public policy. She is a former national political analyst for U.P.I.

Agencies Almost Always Have the Last Word

Photo by Cornerstones of NY

After decades in public housing, Monique Hill was evicted from her apartment at the New York City Housing Authority's Lincoln Houses.

With more than a quarter of a million families on the waiting list for public housing in New York City and some people waiting as long as eight years for an apartment, anyone who has public housing would be unlikely to want to give it up. Two recent cases, though, underscore how difficult it can be for a tenant to fight eviction from public housing.

One involves Monique Hill. She had lived in public housing all of her life except for one period from 2005 to 2007 when she resided in a homeless shelter.

Hill grew up at Vladeck Houses on the Lower East Side where she lived with her mother. In 2007 she and her daughter, then six, moved into Lincoln Houses on upper Madison Avenue. During the total of 29 years she resided in apartment buildings run by the New York City Housing Authority, there had never been a complaint against her.

Then, a dispute with another tenant became physical and led to her arrest for assault. That sparked charges that she was an undesirable tenant, which in turn led to proceedings aimed at terminating her lease. Whether or not Hill was convicted of the assault in Criminal Court, the incident itself, which she described as "incidental contact," was sufficient to constitute a breach of housing authority rules and regulations. She also had fallen behind in her rent.

During a hearing, the Legal Aid Society represented Hill as she sought to defend herself against the assault complaint and chronic rent delinquency as well as failure to submit annual income recertification forms.

Following a mini-trial, an administrative hearing officer at the New York City Housing Authority sustained the charges against Hill. This authority's commissioner accepted the recommendation that Hill be removed from her apartment leaving her with only one recourse: bringing an Article 78 proceeding in State Supreme Court in Manhattan, before an elected justice of the court.

Going to Court

However, the judge -- in this case, Carol Robinson Edmead -- has very limited powers in the face of an agency determination. Whether or not she agrees with the findings she cannot change the result except in very limited circumstances. Was the administrative judge's decision arbitrary? Capricious? Irrational? Unsupported by the evidence? Did the judge abuse his or her discretion? If not, the tenant -- or anyone challenging the final decision of a city or state agency -- is generally out of luck.

Edmead found that the housing authority hearing officer's finding was reasonable an supported by the evidence. "Moreover," she wrote, "the agency's determination involves factual evaluation within an area of the agency's expertise ... and must be accorded great weight and judicial deference."

There is one other test that may be applied, and that is whether the result is so disproportionate to the misconduct, "as to be shocking to one's sense of fairness." Edmead found that the determination in Hill's case was not and dismissed Hill's petition, meaning that the tenancy is terminated and she will be evicted.

Illegal Dogs

Similarly, in another recent case, the petitioner, known only as Florence, sought to reverse the New York City Housing Authority's termination of her tenancy. Florence admitted to having two pit bulls in her apartment that she had failed to register in compliance with housing authority rules.

Besides not being registered, one of the animals had run into the hallway and attacked a neighbor. Also, as in Hill's case, Florence had been in arrears on her rent.

At the Supreme Court stage, Florence brought up the issue of allegedly poor conditions in her apartment, but Justice Alexander Hunter could not consider her allegations since she had not raised them at the agency level. In dismissing the petition, Hunter wrote, "A failure to impose the penalties associated with the applicable rules is unfair to other tenants and enforcement is essential for respondent [the New York City Housing Authority] to maintain its federal funding."

As to the rent delinquency, the tenant, representing herself, had argued that "the unpredictable nature of her work makes it difficult to budget her finances."

This problem, the judge decided, did not constitute an adequate reason for Florence not meeting her rental obligations. Accordingly, Hunter concluded that the agency's findings were not an abuse of discretion, and "the penalty of termination of tenancy does not shock the conscience ... . Petitioner's disregard for the Housing Authority's pet policy along with her inability to make timely rent payments a priority is conclusively proper grounds for termination."

While these two cases involve charges beyond rent arrears, chronic nonpayment or late payment alone has been upheld as a legitimate reason to evict a tenant in countless cases. Judges do have the power to order a case returned to the agency for a new hearing if they find the hearing officer's abused his or her discretion. An actual judge, though, cannot overturn the ruling simply because he or she disagrees with the hearing officer opinion.

Some ruling have been sent back to the agency because they "shock the conscience." These involved instances where tenants were evicted for infractions like not being home at the time of an appointment for an apartment inspection or knocking a clock off a housing authority employee's desk. Such cases, though, are the exception not the rule -- as Hill and Florence have learned.

Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court Justice

With Homelessness Rising, City Looks to Trim Budget

Photo Ed Yourdon

Though there was great fanfare at its introduction in 2004, Mayor Michael Bloomberg's audacious plan to cut homelessness by two thirds within five years and end chronic homelessness in the long term has been something of a failure. This past year saw the highest level of homelessness since the city began recording such numbers in its history.

In its 2010 State of the Homeless report, the Coalition for the Homeless described "a record breaking 39,000 homeless New Yorkers sleeping in municipal shelters each night ... This year, city also saw over 10,000 homeless families in shelters each night for the first time ever."

Despite the swelling ranks, the city's Department of Homeless Services is slated for substantial funding and service reductions in the FY11 budget. The administration and homeless advocates, though, differ sharply on just how severe the cuts are and what effect they will have on services.