Transit Workers/Transit Riders; Beginning Lawyers Are Richer; 9 Million New Yorkers?

More than two months after the end of the three-day New York City transit strike, both the attention and the tension have dimmed. But there is still no settlement in place, and indeed some transit workers have signed a petition to vote again on the contract that had been rejected on January 20th by a mere seven votes.

It would be difficult to say with whom the majority of New York bus and subway riders sided, the transit workers or the management of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. It is a safe bet to say that during the inconvenience of the strike itself, most commuters had little polite to say about either of them.

Since people tend to sympathize with those who seem similar, it is worth looking at the ways in which transit workers resemble, and differ from, transit riders.

Transit Riders

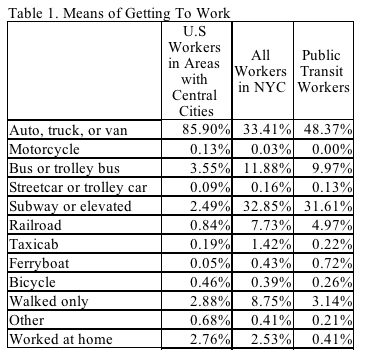

New York City is one of the few places in the United States in which only a minority of people rely on the automobile to get to work. Nationwide, 86 percent of people who live in or near central cities commute by car. In New York City, that number is about 33 percent.

Table 1 offers a breakdown:

It is interesting to note that public transit workers in New York actually commute by automobile at a higher rate than New Yorkers as a whole.

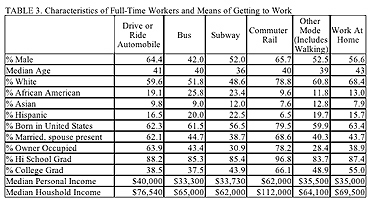

There are also sharp demographic differences among commuters, depending on the means by which they get to work. For instance, those who use commuter rail to come to NYC generally earn more income, live in more affluent households, are more often male, are more likely white, are more often living with a spouse and have graduated from college than those using other means to get to work. They differ substantially from those who drive or ride an automobile, work at home or get to work by other means.

By contrast, those who take public transit are more likely to be black and Hispanic than the other groups. They are less likely to be living with a spouse. They are also likely to have less education. The median income of those using public transit (subway or bus) is about $34,000.

Transit Workers

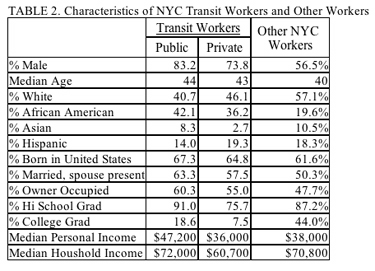

Public transit workers make a median income that is more than the public they service. Instead of $34,000, they earn a median income of $47,000.

There are other differences as well. A larger fraction of transit workers are male and black than the public at large. They are also less likely to be educated, are as a group older than New Yorkers as a whole, and are more likely to own their own homes and live in married-couple households. Despite their relative lack of education, the arduous nature of transit work coupled with their unionized power has led them to a relatively high income.

How this analysis was done.

This analysis made use of the Public Use Micro-sample data from the IPUMS website. Using a variety of variables it was possible to isolate those who work in the public or private transit industry, as well as those who work in New York City and travel to their jobs in various ways.

Young Lawyers Get $20,000 raises

According to New York Observer, a bidding war has broken out among the major so-called Wall Street or White Shoe law firms. New associates are now being offered $145,000 up from $125,000, where it has been for about 5 years. My earlier column on New York Lawyers still seems to be basically accurate, though the figures have increased.

Nine Million New Yorkers?

Is New York growing so fast that it is likely to reach 9 million population in the next two decades? Using recent projections from some private entities a New York Times story indicates that the Bloomberg administration is planning for it. New York City reached over seven million by 1940 and it took 60 years to reach eight million. Could it really reach nine million by 2025? So far, according to census numbers, New York City is growing more modestly than it did in the 1990s. The census recently changed their estimation methods, but the city usually challenges their estimates and is given credit for a few more thousand people. During that decade the census estimated that the city was only growing about 10,000 per year, but it actually was growing about 60,000. We will probably know more when the new fully implemented American Community Study data are released next August. Until then, the Census will issue a new estimate for the population through July 31, 2005 sometime this spring.

Census Says Keep Counting the Prisoners in Prison

Despite the efforts of many in the redistricting and criminal justice communities the Census Bureau says that prisoners should still be counted at the prison sites and that the data should continue to be added to the counts in many small towns and counties. A rider was added to the census appropriation bill asking for a report on this issue. Not surprisingly the Census Bureau did not want to change a thing. The current method deprived the city of thousands of residents, who were moved upstate along with their power to affect the drawing of legislative lines for Congress, and State Senate and Assembly. But at least one New York State County does not use prisoners when they draw the county legislative lines, they think they distort the power in that county.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.Â

Teachers In NYC's Institutions Of Higher Learning

Although few people would see New York City as a college town, the truth is that the city has the most institutions of higher learning in the entire nation, as well as the most students -- and the most teachers as well. At least 25,000 academics teach about 425,000 students in the city's 57 colleges and universities.

These teachers do much for the city, not just educating the next generation of New Yorkers, but also enhancing the city's cultural reputation and strengthening its economy.

But what does the city do for them? As a whole, teachers of higher learning in New York earn less than the city's elementary school teachers. This helps explain some of the current turmoil in academia, with a strike by graduate students having resumed at New York University, and stalled contract negotiations between the administration of the City University of New York and the Professional Staff Congress, the 20,000-member union that represents the faculty and staff of the university.

It Doesn’t Pay To Be An Academic

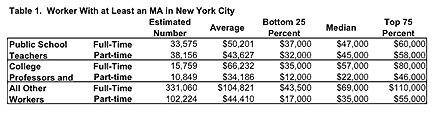

Table 1 (click here) lists most of the institutions of higher learning in New York City, with the numbers of students enrolled, the number of faculty, and their average salary. This varies widely. As a full professor at New York University, you could make $135,000; as an assistant professor at Boricua College, you could make under $35,000. But the truth is, more teachers make toward the lower end than toward the higher. The median income for full-time professors with at least a Master's degree is $57,000 – which is $3,000 less than the median income for all New Yorkers with Master's degrees.

And this is only the full-time faculty; there are no more than 16,000 people who teach full-time in New York at the university level. Another 11,000 who call academia their primary occupation nevertheless teach only part-time; their median income is only $22,000.

Put these two together and the median earnings in the year 2000 of New Yorkers whose primary occupation was academia (and who had at least a Master's degree) was $45,000 – or a thousand dollars less than the median income for elementary and secondary school teachers in the city.

And then there are the many academics who are forced to accept "adjunct positions," which often pay roughly $3,000 per course, or "visiting" (non-permanent) appointments, which also usually are not well paid. (Many of these teachers hold non-academic jobs as well.) In addition, many graduate students do some teaching while pursuing their degrees.

Public Versus Private

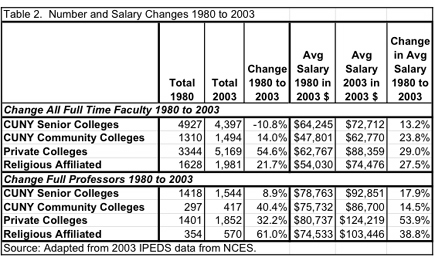

There are a wide variety of colleges and schools in New York City. Below, the "conventional" colleges are grouped into four types – City University senior colleges, City University community colleges, private colleges and religious-affiliated colleges – for the purposes of comparing both the number of faculty at each of these types of institutions, and their salaries.

As you can see above, both private and religiously-affiliated institutions of higher learning have overtaken the public university in many ways. While once salaries for full professors (the most experienced and the most sought after) at the senior colleges of City University were competitive with their peers at the private colleges, now they are far less; the ones at CUNY earn on average about $93,000, while those at non-sectarian private colleges in the city are paid an average of about $124,000.

In 1980, those teaching at religiously affiliated private colleges were earning about $75,000 (or four thousand dollars less than CUNY senior faculty); now they earn about $10,000 more per year. Given these data, it is not surprising that CUNY faculty members are severely discontent with their current salary. (For a breakdown college by college of the difference in number and salary of faculty members between 1980 and 2003, click here).

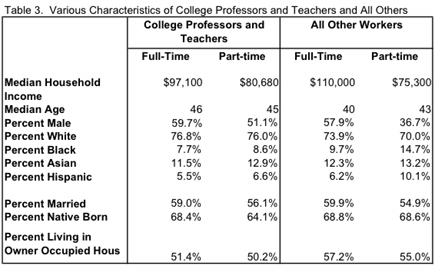

Academics are broadly representative demographically of others with a Masters or higher degree in New York City. Indeed, as Table 3 shows, the major differences between academics and others is that full-time academics have a lower household income than other full-time employed New Yorkers with at least a Masters degree, but other part-time workers live in households with lower incomes than those employed as part-time academics. Other part time workers are much less likely to be male.

Academics in New York City, especially part-time academics are struggling. New York City's large public university in no way is keeping up with the other four-year colleges in the city. Graduate students went on strike at NYU; there are grumblings at Columbia; many CUNY graduate students spend some time in the subway commuting from campus to campus. It is difficult to finish a Ph.D. program, where many students spend five, six, or seven years or more and roughly half leave without the degree . It is difficult to find an academic job, as the recent book Will Teach for Food graphically demonstrates . Swarthmore Professor Timothy Burke's very trenchant Web site "Should I Go to Graduate School?" spells out the perils of an academic career Yet, more academics are produced every year. New York City is still a place that many would be pleased to be if they could find a job, and afford to live here.

A Note on Sources

This column is based upon two sets of public data. The 2000 Census Public Use Micro-Data Samples (PUMS) from the IPUMS site and the Integrated Post-Secondary Education Data System (IPEDS), which includes data collected and maintained by the National Center for Education Statistics, but reported by the institutions. To find academics who worked in New York City, I used various codes from the PUMS data that depicted occupation, industry, type of employer and location of job. I limited my analysis to those with a Master's degree. For the data on colleges and universities, I selected those institutions that awarded at least an Associate Degree, but I did eliminate some that were trade schools or had recently lost accreditation, as well as those that were predominantly professional schools. There may be some differences in definition between 1980 and 2003, and I did not include fringe benefits, but the general patterns of change are robust.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone. Â

Hispanics and the Ferrer Candidacy

Fernando Ferrer was the first candidate of Hispanic descent to run with major party backing for the office of mayor of New York City, and when he lost by a large margin, there was a general consensus among journalists: Ferrer, they said, did poorly among every ethnic group, even -- relatively speaking –- his own.

Some commentators sought to explain this by noting that “Hispanic” no longer means just Puerto Ricans, or even just Puerto Ricans and Dominicans. Hispanic New Yorkers come from many different countries now. Others pointed out that Bloomberg’s polling of voters was very vigorous and very specific, but that it was not based on their ethnic origins. Thus, it was possible to ask seriously whether the mayoral election signaled a new phase in New York City politics -- the beginning of the end of ethnic politics.

There was just one problem with all these explanations and conclusions -- they were based on an inaccurate consensus.

No major news organizations did their own polling; their conclusions about Ferrer’s support was based on an unconventional exit poll.

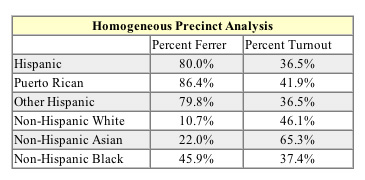

Now more data are available, including complete voting returns for all 6,000 of New York City's election district, as well as a recent exit poll among immigrants. It turns out that the vast majority of Hispanic voters did in fact choose Ferrer -– at least 80 percent. This demonstrates not just that ethnic politics is alive and well in New York City, but that, as diverse as they are, Hispanics in New York share much in common.

An analysis of voting preference in homogeneous election districts (those with high proportions of a specific ethnic group), reveals that Ferrer did very well among all types of Hispanics.

So why did he lose so badly?

First, turnout was markedly low in Hispanic areas. Second, other groups did not vote for him in high numbers; In areas of high concentrations of African Americans, he received less than half the vote, while he got 22 percent of the Asian vote and only 10 percent of non-Hispanic white voters.

A recently released survey by the New York Immigration Coalition produced similar results.

Characteristics Of Hispanic New Yorkers

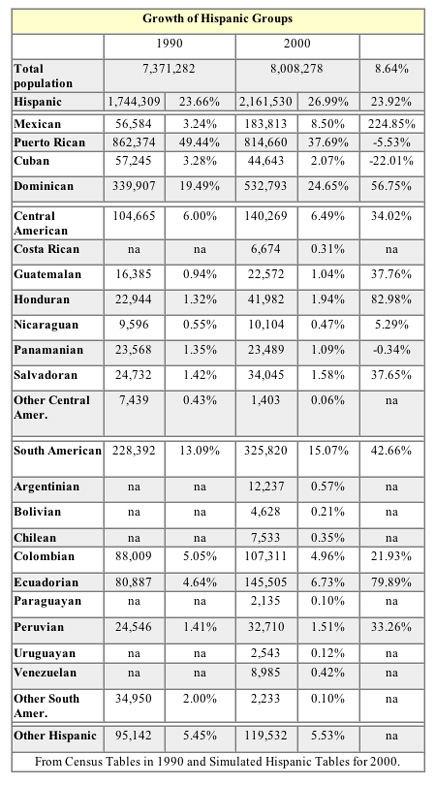

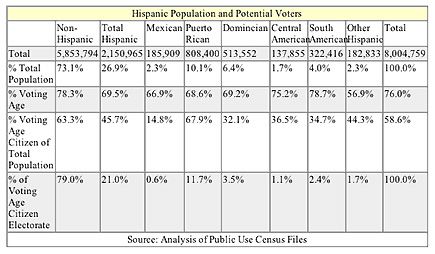

The Hispanic population in New York City is growing rapidly, and becoming more diverse. The Puerto Rican population, which still constitutes the largest Hispanic group in the city, is diminishing. Mexicans have experienced explosive growth. Other groups have grown by at least a third.

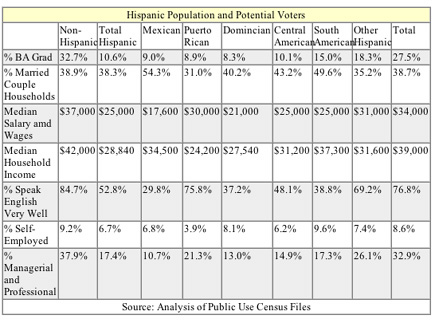

When one examines the social and economic position of Hispanics in New York City it is plain that though there are some variations among the groups, they do face similar economic challenges.

They are less educated, earn less, have lower household incomes than other New Yorkers. A smaller fraction of them speak English "very well." They also are somewhat less likely to be self-employed and much less likely to be employed in managerial and professional occupations.

It is difficult to call them a powerful voting bloc just yet, though, since most of them cannot vote. They are either under 18 or non-citizens.

The Hispanics as a group compose about 27 percent New York City's population, but only 21 percent of citizens of voting age population. Indeed, while for non-Hispanics about two-thirds of the population are voting age citizens, for the Hispanic groups the percent is less than half; only about 15 percent of Mexicans in New York are citizens of voting age.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.Â