Cuomo No-Tax Pledge Could Bring More Transit Cuts

They went down the line -- abolish it, audit it, let the public elect its leaders, put the governor in charge. One-by-one, each gubernatorial candidate castigated the Metropolitan Transit Authority during the New York gubernatorial candidates' debate on Oct. 18.

Almost lost in the shuffle of platitudes and rehearsed one-liners -- "The only difference between the MTA and my former escort agency," quipped former madam Kristin Davis, "is that my agency delivered on-time and reliable service" -- was the fact that, in his comments, Gov.-elect Andrew Cuomo refused to show his plan for the transportation agency.

"It's been unclear what Cuomo's policy priorities are," said Noah Budnick, deputy director of Transportation Alternatives, a New York City transportation advocacy group. "It's hard to know if that means that the door is open and he's willing to entertain ideas. He hasn't ascribed to specific beliefs nor has he said no to anything in particular."

But with the MTA facing ruinous finances, rising fares, reduced service and an unfunded future, the governor will have to take action sooner rather than later. The general consensus in the transit advocacy community is that trimming the fat and implementing more efficient business practices can only do so much to cut expenses.

"Cuomo unequivocally said he wasn't going look to raise revenue for the MTA, that the MTA was going to have to rely on cost cutting and efficiencies," said John Petro, an urban affairs policy analyst at the Drum Major Institute for Public Policy, adding, "I just hope that he has a more comprehensive plan than that."

The Gaping Hole

Despite a series of cost cutting measures and fare hikes, the MTA's budget crunch shows no signs of abating. A recent article reported that a series of moves aimed at bringing in more revenue will fall some $400 million short of what was anticipated. As the agency prepares to adopt an $11.7 billion operating budget , other problems loom, including rising pensions, employee heath care and debt service costs.

Petro, who profiled the decline in a 2009 report titled Solving the MTA Budget Crisis: A Capital Investment Strategy, estimates that the MTA will need to find an extra $1.3 billion annually "just to make sure the transportation system doesn't fall apart," not to mention the extra money needed to even consider expansion and modernization.

The MTA has offered a comprehensive capital program for 2010-2014 that covers all the bases, including needed upkeep as well as expansion projects to keep the MTA on par with other top-notch public transit systems. The price tag: $26.3 billion. Of that, it's estimated that funding will fall roughly $10 billion short over the final three years of the plan.

The plan does not lay out where the funds might come from.

"How the MTA ought to be funded is a question for the legislature," said Aaron Donovan, spokesperson for the MTA. "Our role is simply to make clear the needs that we face and to explain our efforts to overhaul the way the MTA does business."

The legislature, though, has been slow to provide any answers.

"I think the issues involving mass transit are immediate," said State Sen. Jose M. Serrano, whose district spans parts of the Bronx and Upper Manhattan. "I'm not saying I know what the answer is, though. I don't know if increasing streams of revenue is the answer."

The seven gubernatorial candidates offered various answers -- a restructuring of MTA management, increased tolls, raised taxes and fees on real estate developers, selling contracts to private companies, tax-free transit benefits for employers and lower cost transit options. Cuomo has not shown a preference for any of these plans.

Making Drivers Pay

Cuomo has, though, been adamant about not increasing any taxes.

"I have a feeling that for the first couple of years, the main agenda for the governor will be how do we turn this government around? How do we close the deficit?" Serrano said. "And I believe him when he says he's going to do it without increasing taxes."

That has transit advocates and others looking at alternative ways to raise money. One new form of revenue for the MTA is congestion pricing, which essentially charges people to drive into parts of Manhattan during business hours. When Mayor Michael Bloomberg proposed it in 2008, the State Assembly failed to vote on it.

"It will be back," Budnick said. "No matter what financial crisis you want to look at -- the city the state or the MTA -- there’s a desperate need for new revenue sources."

Serrano thinks the legislature's perception of the bill as a rise in taxes might determine the fee's ultimate success or failure. Viewed as a new tax, congestion pricing would run counter to Cuomo's no new taxes stance. Serrano supports congestion pricing as well as levying tolls on certain bridges into Manhattan.

"I don’t know if it's viewed mainly as a revenue stream or mainly as a tax," Serrano said, adding that he would prefer "people view it more as a way to alleviate congestion in the city."

There are a few reasons to expect congestion pricing to factor into the MTA's future. Drivers commuting into the city benefit from having 5 million transit riders off the streets but do not contribute to public transit funding. Budnick calls them "the biggest free riders."

Jay Walder, the MTA's chairman and chief executive officer, oversaw the successful implementation of congestion pricing at his former post as finance director of Transport for London, which manages that city's subways, buses and commuter rails. Started in 2003, London’s congestion pricing reduced traffic by 20 percent in the city and raised 122 million pounds (roughly $183 million) in its second year. Walder avoided taking a stance on congestion pricing when he came to the MTA.

Petro estimates that, optimistically, congestion pricing could raise around $400 million a year. He warns against seeing it as a cure-all solution -- "It's vital … but we need to explore other options."

As an alternative, in 2008, Richard Ravitch, now the outgoing lieutenant governor, recommended the state put tolls on the free East River and Harlem River bridges to raise money for transit. That also failed to make it through the legislature.

At the time Ravitch released a report on the state of New York State's transportation infrastructure, which bluntly began, "New York State currently lacks the revenues necessary to maintain its transportation system in a state of good repair, and the state has no credible strategy for meeting future needs.".

In the past two years, little seems to have changed.

Who's in Charge

In not acting on any of the revenue producing measures, legislators have repeatedly charged the MTA with mismanagement. During the debate, Cuomo did appear to stake out a position on that. "I believe the governor should be accountable for the MTA," he said. "People have the right to know who's in charge and who's responsible, and I think it should be the governor."

What exactly that means in terms of a potential overhaul of the MTA's management structure remains unclear, though. While the MTA is considered a quasi-independent authority, the governor himself directly nominates six of the 17 members of the board of directors, including the chairman and CEO. The mayor recommends four to the governor.

"I think he can exercise leadership, but I don't think a restructuring of the board is useful in the long term," said Gene Russianoff, staff attorney for the Straphangers Campaign of the New York Public Interest Research Group.

The current chair, Walder, has been commended by transit experts for saving $525 million through consolidation of redundant positions, elimination of excessive overtime pay, pay freezes for management and other initiatives.

Historically, a new governor selects his own head of the MTA. Russianoff was one of 11 signatories on a letter sent to Cuomo urging him to retain Walder.

"I don't think much would be gained by replacing Walder with someone who would require a learning curve," Russianoff said. "We've had our disagreements with Walder, but he's been a candid professional and can remain on merit."

Plus, Walder's six-year contract, signed in July 2009, was cleverly constructed so it would be costly for any incoming governor to replace him.

Transit Transition

Cuomo's transition team on transportation could provide some clue of what the governor-elect might be thinking about any of this. Transit advocates are noticeably absent. The panel is heavy on representatives from the private sector.

"First and foremost I think they're about dollars and cents and jobs," Budnick said. "I think that gives an insight into where Cuomo's looking. If you look at the list of who's on the transition team, it's unclear what it implies in terms of his policy priorities."

Pundits point to the disparity between Cuomo's transportation transition team and that of former Gov. Elliot Spitzer, which featured more transportation advocates and labor union representatives. With the contract between the Transport Workers Union Local 100 and the government up in a year, Petro thinks Cuomo may be sending a message with his money-before-policy mentality.

"I think Cuomo thinks that talking about raising revenue before the contract renegotiations is a poor idea," Petro said. "Is that in the best interest for the city and transit riders and for the region's economy? No. The longer we wait, the bigger the hole is going to be. But Cuomo has drawn a line in the sand, so to speak, that he will not look to raising revenue for the MTA without [first] making the point to labor that he expects more efficiencies."

Russianoff, who served on Spitzer’s transportation transition team, believes Cuomo will continue to emphasize cost cutting and management "until the beginning of 2012 when they start running out of money. It's going to look a little different then."

During that span the $525 million Walder has already finagled in savings is expected to rise -- reaching $700 million by 2014, according to Donovan. Those additional savings would come from the deferment of roughly half of the 280 current construction and restoration projects and a thorough consolidation of maintenance operations, inventory management and operations support activities. The MTA already stalled expansion plans and eliminated two subway lines and 36 bus routes last year.

Other Options

In the search for a solution, Cuomo could look some less-discussed revenue options that other cities have tried with mixed results.

San Francisco requires developers to reimburse the government for at least a portion of the cost associated with providing additional public services to people who live in or otherwise take advantage of a new project. In New York, while real estate developers do contribute to transit funding, Petro believes they could afford to pitch in more.

Chicago and London both awarded special contracts to private businesses in return for transit improvements. In Chicago, the government gave Apple Inc. exclusive advertising rights in a station in exchange for the cost of refurbishing the stop. More recently, Chicago announced it is considering selling the naming rights to the various public train lines.

During Walder’s time in London, however, he witnessed the downside of privatization. The city signed a 30-year public private partnership with three infrastructure companies, charging them with maintenance and upkeep of London's underground train system, the Tube. This past May, however, the city bought out the remaining public private partnerships after one of the companies went bankrupt, losing several hundred million pounds of taxpayer money.

With Parking Tickets, New Yorkers Are Guilty Until Proven Innocent

Some things are almost universally avoided whenever possible: jury duty, dental work, parking tickets.

While annoying, each of these serves a greater personal or social purpose. With parking tickets, there are policy considerations and revenue benefits, and the fines serve as an incentive for advancing those policies: keeping parking spots available, allowing street cleaning, helping traffic move.

That does not make anyone want to pay them, though. For many people the main experience they have with courts involves contesting or paying motor vehicle infractions, whether moving or parking. A judge attending a party of non-lawyers can always expect other guests to tell him or her about jury service or the terrible things that happened in traffic court.

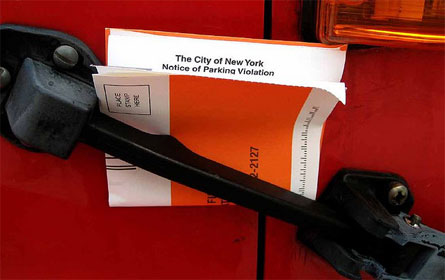

With parking tickets, one issue revolves around the ability to plead "not guilty." New Yorkers can fight parking tickets, but until the final decision is rendered, they will be presumed guilty of letting the meter run out, parking on the wrong side of the street on alternative side parking days or having incorrectly interpreted the often confusing signs that mark streets in many of the city's businesses district.

Fighting the Ticket

A person can plead not guilty of a parking offense by mail, on the internet or in person. The problem though, is that the New York City Parking Violations Bureau and the Department of Finance require the driver or registered owner to pay the fine within 30 days. Pleading not guilty by mail or on the internet may result in a determination more than 30 days later. Paying the fine upon a finding of guilt then could entail a late penalty for the 30 days the not-guilty plea was under consideration. So someone who does not pay the fine, pleads not guilty and is found guilty must pay not only the original fine but also the penalty for late payment.

The Parking Violations Bureau adjudicated 1.27 million parking summons at in-person hearings in 2009, according to Dennis Boshnack, a Queens attorney with expertise in parking violations cases and a former Parking Violations Bureau administrative law judge or hearing officer. Writing in the New York Law Journal, Boshnack maintains that most drivers give up their fight because they are representing themselves and cannot continue litigation alone and/or pay lawyer's fees that can easily cost more than the fine itself. The small amounts of money involved in individual cases make suing the Parking Violations Bureau "unaffordable or impractical."

The Whole Truth?

In one case, Sanford Young, a lawyer, was ticketed for allegedly parking on Manhattan’s Upper East Side at 6:59 p.m. in a spot where parking was not allowed until 7 p.m. He did fight the case and estimated that he spent $10,000 of his own legal time on it.

A Notice of Parking Violation (the summons) was issued to Young’s vehicle as it sat parked across from 1330 First Ave. The summons charged violation of the weekday prohibition against parking in that area between the hours of 4 p.m. and 7 p.m. On Dec. 9, 2005, Young entered a plea of not guilty through the city's website and requested an online hearing. In the field provided to explain the asserted defense, he made the following statement:

"A New York Minute": The ticket, which says I was parked at 6:59 p.m. in a "No Parking ... 4P-7P" area is absurd and wrong! Knowing full well -- as a life long New Yorker and lawyer -- that it is not legal to park on the avenues until 7:00 p.m., and that some officers write tickets in the last few, I did not park my car until a couple of mins past 7:00. I am certain it was past 7:00 because I was watching my car clock -- which is in the instrument panel. I also know that the clock is accurate because I synchronize it with my cell phone which time is set by Verizon and my watch. Therefore, I respectfully ask that the summons be dismissed. Thank you.

By letter, the Department of Finance's Adjudication Bureau acknowledged receipt of the request for a hearing and offered to reduce the fine from $65 to $43. Young did not accept the offer. An administrative law judge issued a decision and order finding the petitioner -- Young -- guilty, saying, "Respondent is not persuasive that he did not park until after the restriction ended."

The Parking Violations Bureau suggested that the agent's sworn summons must prevail over petitioner's unsworn online statement. The city, though, allows written testimony to be submitted through its website, and that testimony is always unsworn. If the sworn summons of a traffic officer would, as a matter of course, prevail over the electronically submitted testimony, submitting it would then, regardless of the facts of the situation, be an exercise in futility -- an illusory alternative to a paper or in-person response. Young's summons was ultimately dismissed in State Supreme Court.

Another motorist received a "red-light summons" for being in a crosswalk after the yellow light turned red. This is not considered a "moving violation" because the offense was detected by photos taken by hidden cameras. The driver pled not guilty, by mail, contesting the position of her car in the photo. Upon a written finding of guilt, she sent a check for the full penalty, $50. However, the city added another $25 because more than 30 days had elapsed since she received Notice of the Violation.

Boshnack points out that when motorists do appeal, the agency may render the case moot by dismissing the ticket and refunding fines already paid. In that event, the case goes no further -- a good outcome for the driver that may reflect the city’s desire to avoid further litigation or to avoid determinations adverse to the Parking Violations Bureau.

Drivers though should not count on that and think they can skip paying the fine. Paying the penalty is a prerequisite for appealing a Parking Violations Bureau decision. The Rules of the City of New York read, "No appeal shall be permitted unless the fines and penalties assessed by the Hearing Examiner are paid, or the respondent shall have posted a cash or recognized surety company bond in the full amount of the final determination appealed from." In other words, payment is due before a determination is made. That might be called a presumption of guilt.

Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court Justice

MTA Moves Toward a 'Smart' Way to Pay Fares

At around 8 on a hot July night, deep inside the Columbus Circle subway station, frustration was on full display. A small group gathered around a bank of MetroCard vending machines, toes tapping, eyebrows raised and arms across chests. While trains rumbled in and out of the station, three young women chatted as they struggled to insert cash into one of the machines. In front of another machine, obviously flabbergasted by what he saw, a thin bearded man exclaimed, "Can't you see it doesn't take bills!"

He continued, "Only one of these damn things does, this one here, I'm waiting for it."

Indeed the messages ticking across the tops of two of the three machines informed MetroCard buyers, this machine "does not accept bills at this time." One of the three also advised, no single ride tickets. All three card dispensers did welcome plastic.

New York's time consuming and often inconvenient fare collection lags far behind that of many other large cities, according to experts. Some might say the dysfunctional MetroCard vending machines reflect deeper systemic problems at the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, one of the world's largest public transit agencies.

Change, though, might be on the way. Within the next few years, transit riders might be able to simply tap their cards and go, rather than having to swipe -- and sometimes swipe again and again. In addition, rather than purchasing a ticket from the transit authority, they could have their fares automatically debited from their bank accounts or charged to their credit cards.

The switchover, though, promises to be lengthy and cumbersome and could present straphangers -- and the authority -- with a new host of challenges.

Ticket Sales

As it stands now, fare collection and the processing of billions of dollars takes a significant financial toll on the transit budget. In 2010, the MTA said that, for every dollar it takes in from MetroCard sales, it spends 15 cents managing and administering the fare collection system. Shaving just one penny off that 15 cents could save around $55 million a year, according to the transit authority.

A team of 124 employees work around the clock to maintain the system's 1,650 MetroCard vending machines.

"We had 28,456 service calls" for machines in July alone, said Antonio Suarez, chief officer of fare collection equipment maintenance at New York City Transit. The machines, manufactured by Cubic Transportation Systems, a unit of the Cubic Corp. have been in operation since 1994.

Meanwhile, a separate revenue office picks up the cash that all the machines hold. The revenue collectors go into the system at various times of day, equipped with gun toting special officers. But the MTA says that budget constraints have "impacted" the frequency of those cash pickups as well as the actual restocking of new MetroCards.

Even though many machines only accept credit or debit card payment, cash accounts for 64 percent of all MTA transactions -- at machine and at ticket booths. The cash transactions are smaller, though, so account for only a third of the fare revenue.

Changing the System

MTA's current fare collection is "a generation behind places like Chicago, Atlanta and London," said Randy Vanderhoof, executive director for the Smart Card Alliance, a multi-industry association.

As riders know, New York City Transit has been slow to embrace many technological advances that could enhance the efficiency and speed of the system . "The MTA has expertise at building and maintaining, they have a poor record at implementing technology,” Said Neysa Pranger of the Regional Plan Association.

The current executive director of the transportation authority hopes to change that.

Jay Walder previously served as managing director for finance and planning at Transport For London. While there, he was widely credited for spearheading that system's wildly popular fare collection system known as the Oyster Card.

The Oyster Card The smart chip uses a secure micro controller, or equivalent device with internal memory, and a small antenna to communicate with an electronic reader through a contactless radio frequency. In London, as well as a bevy of other cities including Chicago, a rider simply taps a pre-paid, agency-issued card or key fob with a smart chip on a specially equipped terminal, like those seen in New York City cabs or at drug stores and fast food restaurants. The cost of the ride then is automatically deducted, as it is from a MetroCard today

Getting 'Smart' in New York

In June, New York's MTA, in partnership with the , New Jersey Transit and credit card issuer Mastercard, re-launched an earlier tap and go smart card pilot program. Plans are to phase in pay systems, first in on city buses and then subways.

In addition to making it easier to pay and collect fares, the plan also would make fare payment between agencies in the tristate area more seamless, helping customers who, for example, take the PATH into the city and then hop on a subway.

In London the transit agency issues a hard plastic prepaid smart card. But signs indicate that New York's MTA would like to get out of the fare card selling business and farm out most of those duties perhaps to the credit card or banking industry. This would happen under what gets referred to as an "open loop" system.

The MTA pilot project is testing whether bank and credit cards embedded with smart chips can be used to make direct payments into the transit system.

Essentially, a rider would no longer have to buy a MetroCard but would simply tap a debit or credit card at the turnstile. The MTA has said it will provide alternatives for cash paying customers but has not devised exactly what they will be.

If New York adopts an open loop system such as that, it "will leap frog other cities" that still issue all tickets themselves," said Vanderhoof.

The "open loop" appeals to public transit agencies, he said, because selling tickets is expensive. "Transit industries across the country are finding it costs them a lot of money, in machines and service, and collecting cash out of them, to be able to operate the transit ticketing and fare payment services they offer," Vanderhoof noted.

No Tickets Please

"Anything transit agencies can do to reduce the number of tickets they have to sell, and the number of machines they have to supply in the stations, will allow them to save money," he said, adding that after all, "people have the ability to pay already in their wallets."

Both London and Chicago are looking at potential open payment options.

The idea has obvious appeal for credit card companies as well. In a case study of the original MTA 2006 pilot program, Mastercard, which had partnered with Citibank, said "Citibank wanted to expand cardholder usage to a desirable everyday category like mass transit, part of the daily routines of million of people."

Columbia University Professor of Law Ronald J. Mann said the incentives for banks and issuers of credit cards to become involved in transit are even greater today.

"They will earn revenues of some sort from transactions on the cards," he said, "and in New York City, there would be a powerful incentive for individual consumers to obtain cards of the type that give them MTA access without having to buy a fare card."

Mann explained that the credit card "market is saturated, the overwhelming majority of people in this country that have any income or assets who want a credit card, have a credit card," so the card companies are looking for new places they can use those cards -- such as transit.

In New York City alone, around 7 million people ride the subway daily, and that could translate into a lot of transaction volume.

Customer Convenience

Vanderhoof of the Smart Card Association said the open loop system could offer added convenience for customers, even those from other cities. For example, he said, someone from San Francisco would be able jump on an New York City subway or bus by just tapping a card she already has in her purse -- "without having to deal with a MTA vending machine."

Mann predicted that "every large credit and debit card issuer will want to be allowed to issue smart cards in New York City.

"Because of the convenience that the ability to use smart debit or credit cards will offer MTA commuters," Mann added, "no one in New York City is going to want to be using plastic that they can't use on the subway. ... You're going to have to figure out which of the banks will give you a smart card, and you are going to go and get it."

Customer Inconvenience

But what about those customers who do not have debit or credit cards? According to the New York City Department of Consumer Affairs, 13 percent of all city households do not have bank accounts -- the largest percentage of adults in any community in the United States.

Mann wondered how people without bank accounts would obtain cards to give them convenient access to MTA services. Will the cards have higher fees than the cards more well-heeled consumers already have in their wallets? And, if MTA completely migrates to the open loop system "will the transit agency move to make it less and less convenient to use cash or buy MTA fare cards?" he asked.

MTA figures for 2009 indicate the average cash purchase was $6.87 per transaction while credit and debit transactions averaged $19.71. That could indicate that some less affluent New Yorkers -- many of whom do not have bank accounts -- simply cannot afford to buy subway or bus rides in bulk.

Amy Linden, senior director of the MTA's New Payment Systems said that eventually, customers without bank accounts might be able to purchase and use pre-paid cards, as many do now for phones, although, she said the authority is not yet testing any of those methods. She said the authority would continue to accept cash on buses.

At some point, riders also many be able to use phones with Near Field Communication, or NFC, technology which might b able to connect to a pre paid account. With that, a transit rider could simply tap the phone on the reader and enter the system. This might help some people without credit cards because, according to Linden, more individuals own mobile phones than have bank accounts.

Even people with bank accounts could face increased risk of stiff customer fees from their banks or card issuer under a smart cart system. For example, customers who overdraw their bank accounts and have overdraft coverage, could be charged a stiff fee when they tap their bank cards to enter the subway.

Further, the plan raises questions about the MTA's fare structure and how the this new payment system might affect unlimited ride plans or volume discounts. For now, the MTA says packages will continue to be available.

Linden said the MTA will deal with all this but first needs to go first to an open payment system since the authority must reduce costs and make travel in the region more seamless.

Making the Change

Whether it can make that vision a reality remain in question. The man who would oversee it all, Executive Director Walder, has an extensive urban planning public sector resume and, as someone who worked for the MTA from 1985 through 1993, knows its complex culture . But, as the Regional Plan Association's Hope Cohen has written, Walder still will confront "interagency rivalries and contradictory union contracts and work rules."

How those pressures, along with public concerns and strained budgets will affect the move to a smart card -- and what the system might look like in the end, is still anyone's guess.

Already, though, the agency's plans appear to be encountering delays. Last year, news reports said a smart card plan would be in place by 2014, but now the agency is not sure when that might happen.

This month MTA spokesman Aaron Donovan would say only that "the new smart card program will see full subway and train implementation in the coming years." He did not provide any more specific information.

Wishing New York the best of luck in its new endeavor, Peter MacLennon of Transport For London said that city's of "tap and go" fare payment system, "has transformed the way passengers pay for journeys on London's transit network."

New Yorkers will have to wait and see if any similar transformations take place here.