Offering New Businesses a Place to Grow

When Michael Bloomberg was fired from Salomon Brothers in 1981, he used the opportunity to create his own business and become one of the richest people in America. Now, with an estimated 65,000 Wall Street employees facing the ax, he is encouraging them to follow in his footsteps.

"Time and time again, history has shown that our city rewards those who have the courage to pursue their dreams and launch new ideas," the mayor said when he announced his plan to revive the financial industry last week.

The plan would provide retraining for those who lost Wall Street jobs, offer seed funds for start-up companies, and attempt to woo banks and financial firms from other countries. To help new businesses thrive and grow, the city would create incubators, spaces where entrepreneurs could find affordable office space and have access to basic services and administrative support. Also announced was a network of available space for incubator clients called the Coalition of Space Providers.

For years, advocates in New York have been seeking official recognition of the contributions they think incubators can make to economic growth. And the city already is home to many incubators of different types and sizes. So how effective are they, and what is the best way to harness their potential?

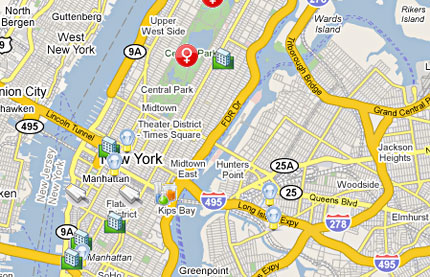

(Go here for a map of all the city's incubators. Do you know of any incubators in New York City that should be on our map but aren't? Go here to add them.)

The Idea Hatches

Incubators generally offer management guidance, technical assistance and consulting to small companies. Often they provide cheap or free space, but "virtual" incubators that provide services remotely -- and do not offer space -- also are common. Once viable, businesses will usually "graduate," moving out into the world.

The business incubator concept is credited to Joseph Mancuso. In the mid-1950s, he was in charge of filling a large complex in Batavia, a small upstate city, but had trouble finding a tenant. So he divided it into small parcels for different businesses that shared office costs. He also provided business advice and helped raise money for them.

One of his original tenants was a chicken company. "In a joking way, because of all the chickens, we started calling it 'the incubator,'" the National Business Incubation Association quoted Mancuso as saying.

Chicken jokes aside, the idea offers special appeal now when so many large, established companies are failing.

"We need to help little saplings grow where the oaks have fallen," said John Tepper-Marlin, a former chief economist for the city comptroller who once used an incubator to launch a company.

"Business incubation is only one aspect of a well rounded economic development policy and not necessarily even the most important one, but it is a strategic one," said David Hochman of the Business Incubator Association of New York State.

The city's and state's environmental sustainability goals have also spurred the push for incubators and led to the creation of the City University's new Sustainable Business and Technology Incubator. "The challenge is now to implement the visions, the policies and the plans into American society," said Tria Case, who is leading the incubator team.

This isn't the first time the Bloomberg administration has looked to incubators to generate new jobs. In 2007, the city offered low cost land, subsidies for infrastructure construction and tax abatements to the developer of the East River Science Park so it could keep its rent low for biotech start ups.

Not Just Business

Some have criticized the mayor's current approach to helping the Wall Street set as one that unfairly benefits those who may already have the funds to start their own businesses and who helped create the current financial mess.

"What about the countless small businessmen and women ... who were running second- and third-generation shops," an incredulous Jeremiah Moss asked on his blog. "They weren't paying down million-dollar mortgages on luxury condos, ordering bottle service, and running up tabs at Bergdorf's -- they were supporting their families and paying the rent."

Some incubators already exist to help these more "Main Street' types.

The Industry City Art Project, for example, is an art incubator in an industrial complex that seeks to shield artists from commercial pressures. "We want to offer artists low-cost space so that financial pressures don't influence their production, which is particularly important for artists whose work may not be commercially viable," said Lise Soskolne, who works for Industry City's landlord in Sunset Park. The landlord funds the project.

One of the oldest incubators in the city assists only non-profit businesses. The Incubator/Partner Project Program at the Fund for the City of New York -- entirely funded with private money -- currently houses 25 small non-profits. Program enrollees receive financial, technical, managerial and legal assistance. Some never leave the program and instead become partners with the fund. "We choose projects based on our belief that they will create value for the city," said Jill Schumacher, the program coordinator.

The Food Bank, a non-profit that got its start at the fund, now distributes 200,000 meals a day to hungry New Yorkers. "The Fund for the City of New York was pivotal in helping to raise money, find space, develop a network for food distribution and assume back office operations," Lucy Cabrera, the Food Bank's president, said in a statement.

Many incubators aim to jump start businesses with social aims.

New York Women Social Entrepreneurs' incubator program pushes to get female social entrepreneurs up and running. Founded in January, it will provide a support team of apprentices and mentors to six women with businesses that have a mission to address a social need in the community. One of its partners is Baruch College's Zicklin Business School.

Green Spaces offers help for green businesses in its Downtown Brooklyn incubator. The project offers affordable office space and services, access to interns, and provides networking opportunities and workshops for small start up companies with staffs of one to five people. Existing small companies that would like to become environmentally friendly also can receive benefits and assistance. Green Spaces, which gets some funding from its building's owner, has only been open for about eight months but already houses 15 businesses.

Economic Impact

There is no hard data on the impact of incubators in New York City, but David Lewis, an assistant professor at the University of Albany, has studied the economic impact of incubators and found positive results. His research shows that nationally, 84 percent of "graduates" stay local once they outgrow an incubator's services. He points to another report from 1998 that studied six technology incubators in New Jersey and found each job created cost only $3,000.

The Virtual Incubation Program at the Industrial + Technology Assistance Corp. generated at least $34.3 million in economic impact within the five boroughs between 2002 and 2008, according to its spokesperson.

And a recent federal report also found incubators to be especially effective. "Investments in business incubators generate significantly greater impacts in the communities in which they are made than do other project types," the Economic Development Administration concluded.

Although they praise the positive impacts of incubators, advocates stress that they are only as successful as their management. To get the most bang for its buck, Lewis says business incubators should conduct feasibility studies before starting their programs, establish client entry and exit criteria, collect outcome data and provide networking opportunities between client firms.

Large incubators are best able to offer synergy among their clients, Tepper-Marlin, the former comptroller economist, noted. He also emphasized the importance of being located near universities. "You need the three-way mix of government support, deep knowledge and entrepreneurial skills," he said.

Government support for incubators should be "offered competitively, with incentives for best practices and accountability," said Hochman of the state incubator association. It should also be programmatic, covering all aspects of an incubator's programming, he adds. As a model, Hochman points to the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority's early stage renewable and clean energy technology program, which offers grants to incubators supporting clean energy companies.

Confronting the Condo Glut

When the Oro Condominiums building in Downtown Brooklyn was still under construction in 2007, the Brooklyn Paper branded it as a "deluxe singles bar in the sky." Now, though, the glitter has apparently faded. On a recent winter night, only a smattering of light emanated from the otherwise eerily dark (though now completed) 40-story luxury tower on 306 Gold Street, not far from the Manhattan Bridge. A hip-looking young woman entering the building, who identified herself as an owner of one of the 300 homes but who preferred to remain anonymous, said the building "feels empty."

A similar picture is emerging across much of the city. In recent years, ordinary New Yorkers saw new condo construction transform their neighborhoods. This is especially true in hotspots like Downtown Brooklyn, Williamsburg and Long Island City, where large rezonings by the Bloomberg administration have spurred the rise of sleek luxury residential towers seemingly overnight.

But as New York City's economy rapidly worsens, people wonder how many of these new condo apartments will languish vacant. Precise numbers are difficult to come by, but government leaders and housing industry experts agree: The condo market is in serious distress.

It is not just the vacant units that are worrisome. In many neighborhoods, half-built projects sit stalled and land cleared for development shows no signs of activity, creating a nuisance for residents who now must live indefinitely with deserted construction sites.

All of this is expected to have a dramatic impact on New York City. But how bad is it, and how might policymakers, housing advocates, developers and financial institutions respond?

The Current Picture

It was not long ago that the condo boom seemed unstoppable, with visions of "botoxing Brooklyn" -- as Faith Hope Consolo, chair of the Retail Leasing and Sales Division at Prudential Douglas Elliman Real Estate, put it -- threatening, or promising, depending on your outlook, to transform the borough's character on a grand scale.

Now, banners hanging from unfinished projects with names evocative of a sleek modernism like "Edge" and "Toren," touting a roof deck, fitness center and library, have, amid talk of a second Great Depression, acquired a surreal air.

New condo development tapered off in the summer of 2007 when the credit crunch began, according to Jonathan Miller, president and chief executive officer of Miller Samuel, a residential appraisal and consulting firm. Initially, this was good news for existing projects because it meant less competition. As time went on, though, the crunch affected buyers, which in turn has lowered sales.

"In general activity is down significantly in terms of number of sales, which is primarily from the credit problem and related to the recession," said Miller.

Bill Staniford, chief executive officer of Property Shark, a firm that provides real estate information, echoes Miller. "Right now we have a glut of supply and no demand." Staniford added that it's not just credit problems that are to blame, but also the downturn in the city's local economy, which relies heavily on the financial industry.

"I have a feeling the financial sector is not going to come storming back to NYC – a lot of those jobs are gone for good," he said. This is potentially devastating for a housing market that boomed in tandem with Wall Street profits. "The bonuses were really the drivers," noted Staniford, "because the bonuses were the down payment."

Tens of thousands of individuals who once got those big bonuses are now out of work and are struggling to keep their existing homes, let alone buy new, more expensive ones. Their parents may help pay the mortgage for now, Staniford said, but eventually these people may decide to leave the city. In that event, their homes will go onto the market, further adding to the glut.

"These people are of means, and they may be running through their savings right now and therefore you won't know they are in distress yet," Staniford added. "I've got a lot of friends in the finance industry – you lose your job and when reality sets in you say I've got to go back to North Carolina or Virginia or wherever I came from."

A Bottom In Sight?

Experts say the worst effects of the economic crisis on the condo market are still taking shape. Staniford projects another 15 to 20 percent drop in value before the end of 2009. "I keep looking at it and I don't see how it stops. I don't think we have seen the complete repercussions of this," he said.

The outer boroughs face particular challenges, according to Miller, because new development there was fueled by the high prices in Manhattan. The notion was that developers would be able to successfully market homes in Downtown Brooklyn or Williamsburg to buyers who wanted a luxury residence but who couldn't afford Manhattan prices. Now, declining prices in Manhattan have undercut that. Many buyers simply no longer need to look to Brooklyn or Queens.

For his part, Staniford worries about the ripple effects of an economy in distress. An increase in crime, for instance, would diminish the quality of life in the city – a recipe for "a perfect storm of negativity for the real estate industry."

"If you have a city that takes a 33 percent cut in revenue from the financial sector, if you keep walking down that path, it just keeps getting scarier and scarier. No one really imagined what is happening now," he said.

Reality Check

Not surprisingly, developers resist painting such a gloomy picture.

Don Capoccia, developer of Toren Condos at Flatbush and Myrtle avenues in Downtown Brooklyn, which is on schedule for completion this spring, says the biggest challenge now is to get prospective owners to sign a contract. "Buyers are spending a lot more time deliberating and comparing and contrasting properties," he said.

While he admits that things have slowed down significantly in the past several months, Capoccia said he has closed two contracts since the beginning of the year at his asking price and without making concessions. He also played down the concern that falling prices in Manhattan are an issue. "Toren has been averaging $750 to $775 per square foot, which is still a great deal even if Manhattan's prices do drop," he said.

But Miller of Miller Samuel says that $750 to $775 per square foot, while still below the rate for a comparable place in Manhattan, does not reflect the market corrections that have taken place since September, when there was a 20 percent drop in values after AIG and Lehman Brothers collapsed.

According to Miller, in September, prices in Manhattan fell from roughly $1,500 or $1,600 a square foot to $1,200 or $1,300. "Apply the same proportional drop – at least half of what it was for Manhattan – to developments (in Brooklyn) priced in the mid $700s (per square foot) and you're talking in the $600s," Miller said. "Brooklyn developers who have not adjusted their prices are receiving little contract activity."

Still, Capoccia insists, his apartments will sell. Citing the quality of the finishes in the condos, he said, "Toren looks a lot different than anything that's coming up right now."

Some experts question, however, whether luxury amenities alone will lure enough affluent buyers to keep these developments financially afloat. In the boom days, Miller said, "If you had the pet spa or the on-site sommelier, that meant something to people," but, he said, it's hard to imagine that dialogue today. "It's the age of austerity now. People are looking for shelter as opposed to lifestyle."

Staniford is matter-of-fact: "Say you have to move to New York City – are you really going to be thinking, 'I need that new fangled pool or gym' or whatever? No you're going to be looking for the best deal you can find."

Holes In the Ground

As bad as things may be for developers with finished apartments to sell, the situation can be even more calamitous for those whose projects have yet to get off the ground.

Developer John Catsimatidis, who is also a potential mayoral candidate, owns a vacant parcel of land on Myrtle Avenue in Downtown Brooklyn, which previously featured a modest retail strip, including an Associated Supermarket that served hundreds of public housing residents across the street. These businesses were torn down in 2006 to make way for a project that was originally supposed to include 1.4 million square feet of new development, of which 250,000 square feet was to be commercial space. The remainder of the project was slated for residents, including 200 affordable units and 600 luxury condos in a 38-story tower and a smaller building.

But nothing has been built yet, and now, with the economic crisis, Catsimatidis, a billionaire, has had to scale down his plans considerably. "We were supposed to build a $500 million dollar project with four to five large buildings and one smaller one," he said, "but banks don't have it. So right now, we're just building the smaller one."

But even for this severely scaled-back version, which will contain 100 market-rate residential units, the financing wasn't easy. Securing a construction loan meant putting up additional cash guarantees, something Catsimatidis says other developers are not willing -- or cannot afford -- to do.

"Banks are saying they want developers to take equal risk now," he said. "We have taken on more risk than we would normally take so that we can get this built."

Catsimatidis has been under fire from residents, advocacy groups and the local Councilmember Letitia James for tearing down amenities such as a supermarket, leaving a hole in the ground and abandoning the idea of affordable housing on the site. Catsimatidis claims that he has had difficulty obtaining bonds that would enable him to build the affordable component. He also indicated that he is seeking alternative options for the land that remains undeveloped, saying he is in conversations with institutions such as Pratt and Brooklyn Law School about building dormitory space.

"The financing is the same as any other project," he said. "But if you have the signature of an institution like NYU, that goes as additional collateral on credit and it's easier to finance."

Policy Mistakes?

While developers are paying the price for the luxury-building binge, they had help in creating it. Many appraisers over-assessed the value of condo properties due to pressure from brokers and owners, which contributed to overdevelopment, according to Staniford. The city is at least partially responsible in the view of Councilmember James, who represents parts of Downtown Brooklyn where new condo construction has proliferated.

"In fairness to the developers, it was a bull market, and real estate was the hottest thing in town. No one anticipated that the economy would crash and that all these toxic mortgages would explode," she said.

James believes that Mayor Michael Bloomberg should take responsibility for the condo crisis. "His policies have been tilted toward the benefit of developers, and not enough towards working class residents. He was basically giving away the house for the purpose of generating revenue from the sale of these high-end luxury condos, not recognizing that it was disrupting stable communities and causing the displacement of long-term residents," she said.

James cited the mayor's zoning policies, which she said should have been designed to produce more affordable housing and jobs citywide. Under Bloomberg, the city has pushed through a historic number of large rezonings that have increased the value of land and fueled speculation. In many cases, such as Downtown Brooklyn, the original intention behind these zoning measures was to promote office space, but instead neighborhoods received an overabundance of luxury housing because of the boom market. The city did not have any policies in place to prevent such an imbalance.

In downtown Brooklyn at least, this new housing was beyond the reach of many longtime residents. At the same time, James said, the rising costs forced out manufacturers who had provided industrial jobs for residents who lack college educations. Such arguments have been echoed in other parts of the city from Williamsburg to Long Island City to the Lower East Side.

City officials have contended that changing obsolete zoning has been key to unlocking the potential of underutilized land and to stimulating the creation of new housing, jobs, public space and other amenities. Attributing the city's loss of industrial jobs to larger economic changes, they argue that rezoning measures combined with investment in public infrastructure has drawn private investment and resulted in economic growth, including an increase in affordable housing construction.

Lost Revenues

Whatever its role in creating the current problem, the city is feeling its effects. The administration has already started bracing for the revenue consequences of a dramatic slowdown in residential property sales and has proposed budget cuts and increases in taxes to close the resulting deficit.

"We're already seeing property transfer taxes and mortgage reporting taxes plummet," said City Councilmember David Yassky, whose district includes the condo-dense neighborhoods of Downtown Brooklyn and Williamsburg. "The city will definitely lose out."

Revenue from these two types of taxes depends exclusively on property sales. (Renters are not required to pay taxes for leasing space.) In the current climate, developers are being forced to convert units that were once for sale into rentals in order to pay their loans. This translates into revenues that, rather than just being delayed due to a slow sales pace, are permanently lost.

According to the mayor's Financial Plan Summary released in January, real property transfer and mortgage reporting taxes combined declined by 57 percent from December 2007 to December 2008. The Office of Management and Budget projects these revenues will fall by hundreds of millions more dollars in 2010 before stabilizing and moving up in 2011.

While the OMB calculates these revenues as a relatively small percentage of the total budget – only 4.2 percent for fiscal year 2009 – they still represent hundreds of millions of dollars the city won't see. This percentage is expected to shrink to 3.2 percent for 2010, with the gap being filled by increases in property and sales taxes.

From Crisis to Opportunity

With general agreement on the existence of the problem, if not its magnitude, government officials, real estate experts and housing advocates are currently debating solutions.

One small step forward occurred on Feb. 12, when City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, in her annual State of the City address, put forth a proposal that would help convert thousands of vacant condo units to affordable housing.

"Capitalizing on New York's recent development boom," she stated, "the Affordable Housing Recovery Program will work to make unsold condominiums affordable to middle income New Yorkers to buy or rent."

According to Andrew Doba, a council spokesperson, the initiative is the result of efforts by a special housing task force created by the speaker a year ago that brought together developers, affordable housing advocates and other stakeholders.

At this stage, the program is still just an idea with few specifics. Before it can move forward, the City Council and the mayor will have to hammer out possibly controversial policy questions and craft a plan acceptable to both. For instance, while Doba emphasized that the goal is to stabilize communities, it is unclear whether the program would include rental units or only those for purchase. According to Doba, the Bloomberg administration has signaled that they like outlines of the proposal so far, which is designed to use capital funding that has already been budgeted.

If the Affordable Housing Recovery Program is implemented, individual developers would have the option to negotiate with the city to make apartments available to middle-income residents, who would qualify based on income. The amount of the subsidy would be determined on a case-by-case basis and would depend on a number of factors, including the original asking price of the units, the debt structure of the project, and whether or not the development is in foreclosure, to name a few.

No one has yet specified even a range of how much money developers might be awarded, but Doba states that it is not intended to bring them windfall profits. But should the city take resources that could go to other programs and use them to fix this problem that developers at least partly brought on themselves?

Brad Lander of the Pratt Center for Community Development, who also participated in the speaker's task force and is a candidate for City Council, supports the idea, as long as the per-unit cost does not exceed the amount designated for other homes in the city's affordable housing program. This, he said, would safeguard the city from over-subsidizing developers and ensure there is more affordable housing in the long run.

"You're talking about developers who speculated in a boom marketplace, who had unrealistic expectations that included no affordable units and who were taking advantage of the 421-a tax break [for housing development]. I do not think we should bail out failed speculators," he said

Lander acknowledged that a lot of discussion needs to take place before the speaker's program can move forward. "It's an idea more than a fleshed-out program," he said, predicting that the implementation process, which will involve looking at buildings one by one, is bound to get messy. "If you're building a totally new development and are interested in taking advantage of one of the city's programs, it's a lot easier because it works the same for everyone," he said.

But will developers come to the table? Yassky believes they will. "You will see the city working with developers to get buildings filled at affordable rates," He said.

This could turn into something of a waiting game, however, as officials calculate the precise conditions needed to justify intervention. "There are some big issues here," said Yassky, "and I think that Housing Preservation and Development and the mayor will want some sense of where the market has ended up." Housing Preservation and Development is still waiting on its new commissioner, Rafael Cestero, who is scheduled to take over in March.

Not everyone feels the city should intervene. "Whenever the city has become involved in the property ownership business in the past, it has been a failure," said City Councilmember Peter Vallone, whose district includes Astoria, where there has been significant new condo development. "People need to relax. This is very cyclical and the economy will soon recover."

Staniford agrees government involvement will only make a bad situation worse, adding that until the market reaches the bottom, gridlock will persist. "What I'm most concerned about is that the pricing becomes accessible for the market again," he explained. "We are still priced too high, and until prices get down lower transactions won't occur."

Beyond Damage Control?

The speaker's press release announcing the recovery program stated, "New Yorkers who were once nearly priced out of their communities will now have a chance to buy or rent one of the new homes that were built in their own backyards."

To affordable housing advocates focused on the effects of gentrification and displacement, this statement surely reflects a certain backward logic. Still, many support the basic spirit of the program. Ismene Speliotis of New York Acorn's Housing Here and Now initiative participated in the city's housing task force. She views the current crisis not only as an opportunity to increase levels of affordable housing, but also to adjust policies that were skewed in the first place, which will promote more equitable approaches to development over the long-term.

Speliotis says the Affordable Housing Recovery Program is a good idea, but the city should not have subsidized these developments to begin with. "Acorn had done a study when these buildings were being built -- Sweetheart Development -- and was completely outraged because developers were getting an automatic 10-year tax abatement, " she said. Affordable housing advocates have long objected to what they view as an extraordinary level of public subsidy for market-rate housing that would have been built anyway and criticize the city for not extracting greater public benefit in exchange for such subsidies. The rules on the subsidies have been tightened somewhat, but for years they went to anyone who built housing -- regardless of how expensive it might be.

Putting together a program that does not reward developers for having built vacant housing poses difficult challenges, Speliotis acknowledged. "You've got legal, financial, and then kind of just the psychological hurdles, the perception of the market and what is going to happen," she said. "But in our view, if developers convert some of these empty units to affordable housing, people lose less money. They make less profit, but still, one could define that as an opportunity."

Amid all their disagreements, though, experts do seem to agree on the resilience of New York City's real estate market. For Miller, it's just a question of time. "People are anxious to get things back to where they were, but unappreciative of how long it's going to take," he said. "Time is a four-letter word right now."

Staniford concurs, albeit from a slightly different angle. The real question, he said, will be what's going to replace all the financial sector jobs. But he remains certain something will: "There is no doubt in my mind that New York City will come back again. The place is just way too unique. There is great energy here."

Allison Lirish Dean is a journalist, urban planner and filmmaker. She lives in Brooklyn.

Bike Lanes Run into Opposition

Protesters showed up in clown suits. Their opponents threatened to barricade a major thoroughfare with school buses. A respected community board member was fired from her leadership post. The debate has involved lost jobs, injury -- and even sex.

The source of all this controversy and activism? A bike lane.

With concerns about pollution, congestion and energy consumption, encouraging people to cycle instead of drive could be seen as a kind of motherhood and apple pie issue. But as the Department of Transportation greatly expands New York's bicycling lanes, it has encountered opposition from local small manufacturing businesses, the Hasidic community and shop owners, among others.

"We would never have predicted that bike lanes could provoke so much upset," Gowanus Lounge once observed after a community meeting on bike lanes, adding that a member of a local civic group said the issue "led to the most contentious meetings they have experienced, including discussions of Atlantic Yards."

Some of the controversy undoubtedly stems from the frenzied competition for New York's streets with motorists, cyclists, trucks, pedestrians, skaters and baby strollers all jostling up against each other for safe passage. Some critics, though, say the city, in its drive to expand bicycling, has not always consulted sufficiently with the affected communities .

Birth of a Bike Lane

The fight over the bike lane on Kent Avenue in Williamsburg has proved particularly contentious and shows no signs of abating.

Like many thoroughfares near the waterfront in the outer boroughs, Kent Avenue can feel like a desolate concrete valley. Big trucks gun their engines as they make their way to and from downtown Brooklyn, creating a noisy, dusty and dangerous situation for pedestrians and cyclists.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg's administration has sought to change that, and transform the area, along with other parts of the city's waterfront, into a vibrant ribbon of accessible open space and new high-rises. To achieve this, the administration sought to rezone the neighborhood in 2005. When elected representatives and residents balked at high-rises along the waterfront, the city offered three major incentives: open space with access to the river, affordable housing and retention the manufacturing jobs that have long sustained the neighborhood's working-class population. The rezoning was approved, and two years later, the city added the bike lane to the mix

In April 2008, Department of Transportation officials appeared before Community Board 1 to present the local segment of a greenway that would eventually stretch from Sunset Park in the south all the way to Greenpoint. Their drawings showed both lanes of bike traffic together, separated from cars and trucks by a planted divider. Until funds were available to build that, the transportation department representatives said, Kent Avenue needed a temporary bike lane because the street was dangerous without one.

That temporary design would involve a bike path along Kent, from Clymer Street to Quay Street. It would eliminate about 500 parking spaces, but the officials said parking on side streets and at new developments on the waterfront would replace them. These private buildings, when complete, would provide about 3,500 new parking spaces.

Originally, many residents were excited about safe bike routes along the river. In April, the community board voted 39 to 2 in favor of the long-term plan. But when the bike lanes were finally painted, problems appeared almost instantly. The lanes did not look like the ones in the pictures. They ran along both sides of the street, surprising even cyclists. And the signs that accompanied them did not just forbid parking, but all stopping at any time. Hasidic Jews charged the city first posted the laws banning parking on Kent at 6:30 a.m. on Saturday, when observant Jews are forbidden to drive and that traffic agent ticketed their cars.

Block the Dock

Businesses charged that the new bike paths prevented them from legally using their loading docks. David Hollier owns a high-end furniture shop that employs 10 people, most of whom, like Hollier, bike to work. The business requires Hollier to load and unload heavy pallets of fine wood almost every day. He does not see why he should lose access to his loading dock because of the bike lanes.

About 20 businesses on Kent raise similar concerns, including the glass producer Goldray Industries and Acme Smoked Fish.

The business owners say they were surprised by the new signs forbidding stopping in the bike lanes adjoining their loading docks. "They didn't even put a flyer on the door," Hollier said.

Karen Nieves, business services manager for the Greenpoint Williamsburg Industrial Business Zone, said she is "deeply disappointed in the lack of outreach for this plan." She thinks it could threaten the very survival of some of the manufacturers, all of whom together employ about 300 people.

The Department of Transportation insists it did all the outreach required when it addressed the Community Board on three separate occasions. If any groups didn't know enough about what has been going on the past two years," said Teresa Toro, who headed the Community Board's Transportation Committee until she was ousted late last year, "they should reach out to their representatives on CB1 and ask why they haven't kept you properly informed."

Living on the Lanes

The residents offer a different set of concerns. Most are Hasidic Jews and Latinos who live in "affordable" apartments set aside in new high-rise buildings. Since the area is not well served by public transit, many families rely on cars, and the parking spaces in the basements of their buildings are beyond their means at about $325a month. Now, residents complain, street parking is hard to find, and the ban on stopping in the bike lans means they cannot drop off or pick up family members anywhere near their homes.

The residents, like the business owners, say they did not receive adequate warning about the full effects of the bike path. At a Nov. 24 town hall meeting on transportation issues, Hasidic members of the Community Board said even they had not understood what was coming. Isaac Abraham, a Hasidic activist running for City Council, reminded representatives of the Department of Transportation that he helped organize a blockade of the New York marathon 20 years ago to protest a temporary closure of the Brooklyn Queens Expressway. If the lost parking spaces were not restored, he said, he might consider a similar move, blocking Kent Avenue with school buses.

Reaching a Compromise?

So far, the bike lanes remain. At a community board meeting in January, bike lane supporters showed up in force. City officials have not shown any public sign of wavering, although the Department of Transportation's borough commissioner, Joseph Palmieri, has tweaked the plan a bit. The department now allows bus pickup in front of the Zafir Jewish Learning Center. It temporarily eased up on issuing tickets for blocking the bike lanes and installed a loading dock for one manufacturer, Carriage House Papers. The owner of Carriage House, though, said the loading dock is useless because she has to circle the block to use it.

Meanwhile, discussions continue. A number of local leaders and politicians have written to the transportation department demanding the bike lane on the east side of the street be removed and parking restored. Councilmember David Yassky has put together a committee to consider alternative solutions, including the possibility, endorsed by some neighborhood activists, of making Kent Avenue into a one-way street.

Fueling the Opposition

Kent Avenue isn’t the only place where the city’s transportation planning has run up against the concerns of local business owners and residents. Wiley Norvell, communications director at the cyclist advocacy group Transportation Alternatives, sees people come out to fight nearly every mile of bike lane the city builds.

In Fort Greene, for instance, residents opposed five miles of lanes, marked by striped pavement, along Carlton and Willoughby streets in June 2006, and the community board voted against the plan 16 to 15. But the Department of Transportation went ahead and implemented the plan anyway, and few residents have complained since.

That case was typical, Norvell said, in that the opposition to the bike lanes was not so much about local issues but rather "a referendum on cycling as a form of transportation." About 80 percent of the negative comments about bike lanes, Norvell said, simply criticize bikers as jerks who don't follow the rules.

The lack of a true consultation process with affected commuities, though, makes the bike lanes a harder sell, Lower Manhattan offers another example of how the city's transportation planning can run up against the concerns of local business owners.

Last fall the Department of Transportation began installing a new bike lane on Grand Street between Varick Street and Chrystie Street through Soho, Little Italy and Chinatown. Presenting the bike lane as an important connection from the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges for commuters into Lower Manhattan, the department's plan consisted of an northern lane for commercial loading and unloading, a lane for motor traffic, a parking lane, a buffer and a bicycle lane along the southern curb. In July the proposal passed the board with a vote of 33 in favor, 1 against and 1 abstention.

Opposition from some business owners materialized, however, as the bike lane was installed. A few in the business community felt they had not been sufficiently consulted or educated about the changes.

The protected lane with the buffer between car and bicycle is intended to make bicyclists safer and keep the bike lane clear of double-parked cars and other vehicles. It also has narrowed the street, though, and some business owners contend this makes it more difficult for large tour buses to navigate. As a result, they say, fewer tourists have patronized their businesses.

Others dismiss any correlation between the bike lane and decreased businesses, attributing any falloff in customers to the declining economy rather than the bike lane. In a December op-ed article for the Villager, restaurateur and Soho resident Florent Morellet wrote the Grand Street bike lane creates a more orderly and a safer thoroughfare.

Transportation Alternatives’ Norvell agrees. "It is a much more orderly environment," he said. "I think overall the street configuration is in really good shape." Grand Street was remodeled from one and a half lanes of traffic, which led motorists to jockey for position, exacerbating congestion, to a single lane of motor vehicle traffic.

A bike messenger, though, was less enthusiastic about the lane. "It doesn't keep pedestrians out of the street. People see it as another place to walk," he said. On a recent afternoon postal workers and a deliveryman pushed carts through the lane.

Concerns raised earlier this winter over congestion and an overly street maybe easing. "I wouldn't worry about all that gossip," said a part-time worker at Ferrara Cafe. Concerns that the bike lane has made tourist access too difficult were played down. "This is a very well known place, known all over the world."

The current attitude on Grand Street seems to indicate that, in general, business owners, residents, and cyclists agree that bike lanes are a good thing for safety and for the environment. The problems many have is the way the city goes about implementing its policy to expand bike lanes.

"How are you going to make it 'no stopping at any time' and not let them know?" asked Nieves of the Greenpoint Williamsburg Industrial Business Zone. Taking consultation beyond the community boards and doing some more direct outreach might make for a far smoother ride.