Going Back In Time To Vote

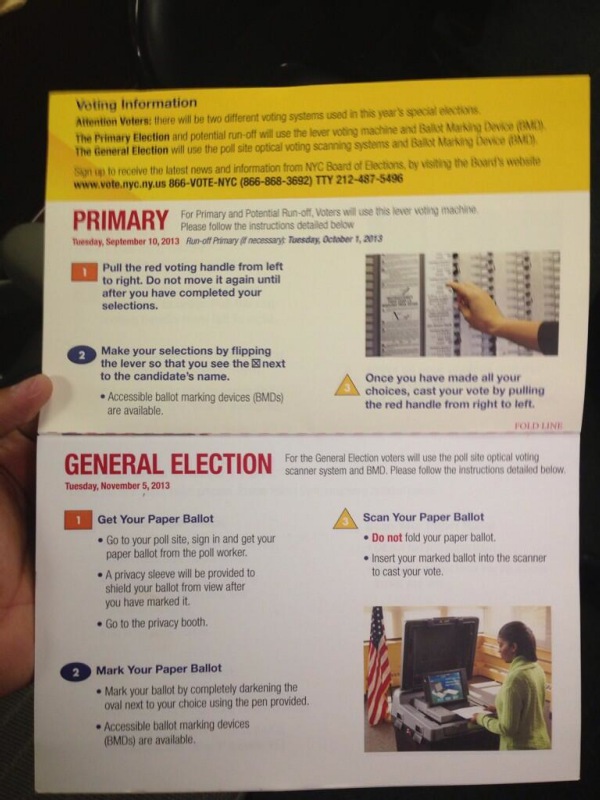

ALBANY, N.Y. — Going to the polls this year could be like stepping back in time to another era when voters had to pull down on levers to make their ballots count.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed legislation today allowing the New York City Board of Election to bring lever voting machines out of storage for the primary election and likely mayoral runoff. The city has been using electronic voting machines since 2010.

In an approval message, Cuomo called the plan a "poor solution" but also said not signing the bill could be worse.

"Preventing the use of lever voting machines through a veto could profoundly impact the integrity of this year’s elections," Cuomo wrote. He signed the law in private.

The measure also delays the runoff until Oct. 1, from Sept. 24.

Citing numbers from the latest Quinnipiac poll showing City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, former Congressman Anthony Weiner and former Comptroller Bill Thompson in a statistical three-way tie, BOE attorney Steve Richman defended the need for the lever machines at a public meeting earlier today.

"If the margin of victory is that close — and we can only look at the latest polls which show the three top candidates all within a point and a half of each other — that that's something to be done," Richman said before taking a jab at opponents to the BOE's lever solution. "I guess its more important to use, for some people, the scanners than to actually accurately count the votes."

Seven of the nine BOE commissioners approved a resolution on the plan to use the lever voting machines.

BOE Commissioner Naomi Barrera said the Legislature had "tied their hands," referring to efforts by the board to get state lawmakers to move the primary to an earlier date to allow for more time for a runoff.

"We have no choice but to go back in time," she added.

"Hopefully we're not in this position next time around," said Commissioner Simon Shamoun. "But going around the city and speaking to different groups and people — the support for lever machines among voters is overwhelming …I get almost nothing but positive reception."

Board President Frederic M. Umane and Secretary Gregory C. Soumas were absent and did not vote.

Good government groups had opposed bringing back the lever machines, arguing that deploying antiquated machinery would lead to confusion at the polls. They also argued that the lever machines were difficult for disabled voters to use.

They called the plan a "half-baked solution that seeks to absolve the responsibility of the Legislature in creating a crisis borne of their own failure to act."

But the BOE had argued that it would be unable to calculate the results from the Sept. 20 primary with its electronic voting machines and get them ready in time for a runoff election, initially arguing that the primary date be moved up to June. After failing to convince state lawmakers that the date change was necessary, the BOE asked the Legislature to empower them to use the lever voting machines.

The original Senate bill proposed by Republican Sen. Marty Golden, of Brooklyn, would have allowed for the use of the lever machines for any non-federal election. But good government groups said that could set a bad precedent that would allow for their return in the future under other circumstances. That provision was eventually killed.

The measure that was signed into law limits the use of the machines to the primary and runoff.

In his approval message, Cuomo listed a number of fixes the BOE could enact to prevent the need for lever voting machines Cuomo also suggested the BOE change it’s hand-count requirements and use high-speed scanners.

Elections Systems & Software, the maker of the city’s electronic voting machines, had offered the BOE faster electronic ballot counters for free if the BOE continued to use them for ballot printing or charge them $1.5 million for the counters outright.

The BOE rejected that offer, saying the counters would violate state law.

Sen. Adriano Espaillat, whose attempt at winning a seat to Congress was complicated by the messy handling of the 2012 election by the city BOE, slammed the approval of lever voting machines but said he agreed with Cuomo.

“I share Gov. Cuomo’s disappointment that the BOE pushed for this short-term tactic instead [of] pursuing meaningful reform. I stood with every good government group in New York City to oppose this plan,” Espaillat wrote. “The abandonment of federally compliant voting machines for the 2013 primary is a setback towards the goal of bringing sunlight and accountability to a troubled organization."

—

Soria contributed to this report from New York.

Spitzer Wants Back In The Political Game

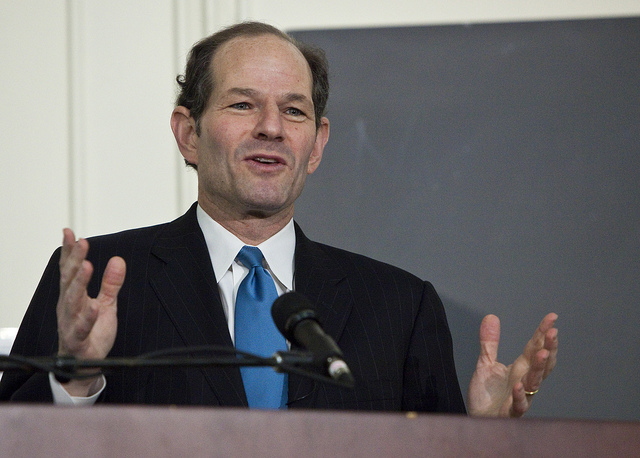

NEW YORK — Eliot Spitzer wants to get back into the political game. The former governor made the surprise announcement yesterday that he is running to be the city's chief financial officer.

Standing in his way and his ambitions: A few thousand signatures he needs to get on the ballot in less than a week, a frontrunner with little name recognition and a reputation marred by a pesky prostitution scandal that derailed his political career back in 2008.

Spitzer's bold attempt to return to the public sphere was immediately compared to disgraced former Congressman Anthony Weiner's bid for mayor. But, as top political reporters have pointed out, that comparison is rickety: Where Weiner's accomplishments as a legislator have been dubious, Spitzer got results — even if his aggressive tactics earned him the moniker of "steamroller" over the years.

The scandals that led to their departures from political life were also decidedly different.

"While Weiner’s crotch-picture scandal has a creepy factor, Spitzer’s involved the world’s oldest profession, and he did not exacerbate the personal damage by clinging to his office," Politico's Maggie Haberman wrote. "And unlike Weiner, Spitzer has a long list of accomplishments in office to point to."

Spitzer made his announcement to the The New York Times. He told the paper he hoped that "there will be forgiveness."

"I love public service," he told the Daily News in a separate interview. "I believe in it and hope I will be given a second chance."

Spitzer has only until Thursday to get 3,750 signatures from registered voters to get on the ballot.

He told the Times about 100 people to begin gathering signatures today. He also claimed that he would fund his own campaign out of his fortune rather than turn to the city's public financing system.

Spitzer's decision upends a sleepy race for the office of comptroller. Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer, facing no competition for the Democratic primary until now, was expected to take the race handily. The current comptroller, John Liu, is running for mayor.

Politicker posted this statement from Stringer's campaign manager:

“Scott Stringer has a proven record of results and integrity and entered this race to help New York’s middle class regain its footing … By contrast, Eliot Spitzer is going to spurn the campaign finance program to try and buy personal redemption with his family fortune. The voters will decide.”

Stringer's supporters took to social media to praise the candidate and bash Spitzer.

In his interview with the Times, Spitzer said he wants to transform the comptroller's office "into a robust agency that would not merely monitor and account for city spending, as it does now, but conduct regular inquiries into the effectiveness of government policies, in areas like education." That, said the Times, could put Spitzer "into conflict with the city’s next mayor."

To be fair, Liu has used the office to take on a broader array of subjects and to challenge Mayor Michael Bloomberg's administration in a number of public policy areas. But Spitzer would likely bring his experience serving as state attorney general to bear in making over the comptroller's office into a more aggressive watchdog.

The city's official primary election debate for comptroller is Aug. 12. The comptroller earns a salary of $185,000 a year, according to the city's Campaign Finance Board.

In Conversation: Mayoral Candidate Bill De Blasio

NEW YORK — Bill de Blasio, the public advocate and Democratic mayoral candidate, first got elected to city government in 2001. Well known within political circles but not yet a household name, he is seen as the liberal choice in the mayoral race, angling to represent the increasingly assertive influencers living in the outer boroughs, especially in the "new Brooklyn," where he resides with his family in Park Slope. In a recent interview, he spoke to the Gotham Gazette about the city's budget, the role of the private sector in public education and the need to reform the public housing agency.

GG: The Department of Education has received considerable financial and professional support from the private sector. What role should the private sector — either business people or companies — play in financing, shaping or steering the DOE and its policies?

DE BLASIO: One, I want to continue the charitable support we get obviously. Two, I've said, not to the private sector, per se, but to folks who've done well financially — I've proposed a tax on the wealthiest New Yorkers, those who make a $500k and more for five years — I think that will be a game changer in our schools. The money would go to early childhood and afterschool programs at the middle school level. I think that will profoundly improve our school system and the rest of the resources will be better utilized because we are building a stronger foundation.

But in terms of the role of the business community in schools, I'd like to intensify it, first at the high school level on down to the middle school level to the maximum extent possible, linking individual businesses and or sectors, tech sector, film, TV, media etc., to specific schools.

GG: How does that work?

DE BLASIO: I think one of the things that's happening is that a lot of young people, aren't being given a sense of a pathway, after school. A lot of folks are going to have trouble affording higher education or completing it, because of the cost. Right now, our school system, including our approach to career and tech education, really doesn't key into the current economy and where the jobs are going to be, in the economic future.

But, if you link, a specific business to a school, that comes with internships, mentoring possibilities, that really changes our approach, and certainly what young people get to see as possible for their future. So I want the business community deeply involved.

And, in terms of strategy, when it comes to career and technical education, we should be regularly sitting with leaders of the business community to figure out what skills we should be teaching to help prepare our workforce of the future.

GG: Throughout much of the budget process, the mayor's Office of Management and Budget has been criticized by some observers because of what they see as a lack of transparency. As mayor, what will you do to make the OMB be more accountable to both the public and elected officials.?

DE BLASIO: A lot of what we do with the budget process can only be described as primitive, it's based on a lot of secrecy, not allowing the public to know what the real revenue projections are, you know, playing games with that.

I don't even need to go into the problem of member items in the City Council, which I've called for abolition of, the way that the budget process keys in on the mayor offering the Council, a very small amount of the budget, and using that as a tool of political control, how the Council speaker uses that same small allotment to control the members as opposed to actually having a larger public debate on our budgetary priorities and where the real money is.

The Council is arguing over that small amount of funding they get to work with. That is less than one percent of the overall budget. The big questions are, what are we doing with our major choices, like education, affordable housing, health care? Those are things we put a huge amount of money in.

I want to move us to a more mature, more transparent, more publicly involving approach, somewhat like what you see at the Congressional level. And I think the public needs to have a role from the beginning.

GG: I have to ask this. There's been some press and a lot of talk, in particular the mayor himself, about what some are calling New York's coming fiscal cliff. Some have put the figure owed at around $7.8 billion, and one of you is going to inherit that. Unions in the city haven't gotten any new raises in over four years [Editor's Note: Clarifies that there have been no new raises. Union members have received incremental salary increases under old contracts]. How do you foresee handling that?

DE BLASIO: Look, I have confidence that we can work our way through it. I think everyone knows they're going to have to make compromises in this process. The Bloomberg approach had two features that I think we really need to move away from. One was the irresponsibility of not dealing with the contracts as they came up. As mayor, well, I'm watching the Bloomberg example carefully to know what not to do. You have to deal with these things in real time. It's like any household budget, when you let stuff build and build it becomes insurmountable. But, two, is the mayor has often used his bully pulpit to attack municipal labor. And, interestingly, that has correlated with his inability to get realistic agreements including some of the productivity changes we need because the attacks have just hardened the position of municipal labor.

GG: So, as mayor, how would you engage municipal unions on this issue?

DE BLASIO: What I plan to do is sit at the table with union leaders and say look, here's our financial reality. We want to try and do that which we can for you. We can only do that with what we have and we can't surpass the resources we have — we are legally obliged to balance our budget. So, what I will ask of every union, is show me every kind of savings, every kind of productivity improvement, and tell me your priorities. And then I'll tell you what I have to work with. I'll tell you the different policies we can work together on to improve working conditions, etc. And we'll come to some kind of balance point.

And I'm convinced, even if it means, if it takes several years to resolve all the outstanding issues, and stretch out some of the payments, so we can afford them, we'll get through it.

But we'll only get through it if there's a cooperative atmosphere, and if we treat labor leaders like they're mature people, who know how to handle a difficult situation, certainly the experience in the 1970's fiscal crisis suggests that when treated as partners labor can be fair and balanced in their approach.

GG: On to real estate and climate change. In light of the widely held assumption that our sea levels are rising, what will be your specific approach to waterfront development. How will you work with the real estate community on construction issues related to climate change? Some say developers could stand to lose with stronger restrictions — then again, could they stand to profit from smarter building science?

DE BLASIO: I think more the latter. Look, I'm going to borrow a couple of pieces from Bloomberg, then an important piece from Cuomo. I think Bloomberg is right, we are a coastal city and we should not assume otherwise. There's climate change, we have rising sea levels and we're going to face greater challenges than before, but, that does not mean a retreat, it means changing how we build.

I think it's fair to say, even taking the extraordinary example of Sandy — and Sandy really was a quote unquote perfect storm — when you look at all the things that sort of happened simultaneously to make it have the impact it had, had we had in place the kind of building codes the mayor is proposing now, such as generators weren't in the basement, we would have had a very different outcomes.

So I don't think we have to retreat, but we have to build very differently. I think that will afford perfectly good opportunities to the real estate industry to continue to profit. They're doing very well right now. Values in this city are extraordinarily high and the appeal of this city is extraordinarily high and I don't think that's going to change.

I think the governor made the point that some of the low lying areas, even areas that are below sea level such as a few areas on Staten Island, we have to incentivize people to move from areas that are no longer sustainable for the long term. I think we have to see how far we can go with the incentivization, and hopefully get that to work. But, that's a fairly small number of areas. But even the Rockaways, which was hit so hard — I agree with the mayor's focus in his plans, for example, [for] dune restoration and wetlands restoration. These are approaches that have been working around the world.

But even in the real life example of the Rockaways during Sandy, some areas that had built up the dunes, did quite well; other areas, of course, were hit very hard. I'm optimistic we have of the tools and, thank God, we have a lot of the federal funding, not everything, but a lot, and we will find a way to make the right adjustments and continue to be a successful coastal city.

GG: This year, news came out that the city’s Housing Authority had yet to spend nearly $1 billion in federal money despite a backlog of complaints from residents seeking repairs and a growing waiting list of applicants. In June, NYCHA announced that it would cut back on services and lay off staff due to $205 million in budget cuts resulting from the federal sequestration. How do you make NYCHA more accountable to taxpayers and residents? And what would your administration do to address the agency’s ongoing budget problems?

DE BLASIO: To the first point, just about affordable housing in general, there's an affordability crisis in this city and it cannot be solved with business as usual. The Bloomberg administration was often very lenient to the real estate industry. And, when you look at the final figures on the Bloomberg years, and the affordable housing they created or preserved verses that which was lost because of loss of Mitchell Lama units, rent regulated units, we really didn't end up with much of a net of affordable housing.

So, the plan I put forward, 200,000 units, is based on a much more aggressive approach by the public sector towards the real estate industry demanding that affordable housing be a part of every major development and be required, mandatory inclusionary zoning. And a series of other steps, investing pension fund dollars etc.

The big point, I want to make, is that we have to change a lot of our approach to housing or a huge number of people will not be able to live here. We will not be an economically diverse city. And we have to continue to be an economically diverse city.

GG: And public housing?

DE BLASIO: The current Bloomberg plan I do not support because I think it was rushed, as so many other things the mayor has done lately. I don't think it makes clear to public housing residents that we will disallow privatization, I think residents worry its a first step towards privatization of public housing units, which would be fundamentally destructive and unacceptable. It didn't involve community members properly in the process and doesn't offer guarantees in terms of employment or where any resources from development will go to people in the surrounding areas.

I think its an ill conceived project that has to be stopped. I think the next mayor needs to look at the whole question of any available NYCHA land very differently, and start with the residents and what will benefit the residents of NYCHA and start with some of these huge repair backlogs.

GG: What about that billion dollars?

DE BLASIO: The billion dollars that has not been spent effectively is a huge problem but the bigger problem, in my opinion is that there's been a history of inefficiency at NYCHA and poor labor management relations. A lot was not done, with even the money we've had.

As public advocate, the number one complaint that I got, is from public housing residents calling about serious repairs, they needed health and safety oriented repairs, and not being able to get them, even after years of being on a wait list.

That showed me, and we've researched this extensively, that NYCHA is simply not professionally managed. And we have to go back and do some serious restructuring, not just at the board level, but on the whole managerial approach and the labor relations.

Beyond that, we have to find a way to change the federal government involvement which used to be much, much greater in NYCHA, that's going to take time, but it's something I believe ultimately can be achieved because of the importance of New York City to the future of the nation's economy.

So a lot of different pieces, but it starts with much deeper reorganization of NYCHA to make more efficient use of the money we have now.