After Cuts and Firing, Can Agency Still Protect New York's Environment?

Photo by Astoria4u

The clean up of Newtown Creek (above) would be in jeopardy if New York withdrew from the federal Superfund program.

"Pete Grannis was fired by Gov. Paterson because he had unpleasant news about what his planned cuts would mean to the state," said River Keeper executive director Paul Gallay.

Many activists and others agree. When Gov. David Paterson fired Department of Environmental Conservation Commissioner Pete Grannis in late October, after a memo leaked detailing how cuts would prevent the agency from protecting the environment, legislators and environmental activists joined together to denounce the move and praise Grannis' long service. Grannis denied leaking the memo.

"They shot the messenger," said Gallay.

While controversy over the firing still rages, advocates say the focus must now shift to the agency itself and if it can protect New Yorkers and the environment with cut after cut. "We need to move on and focus now on the memo and what it says about this agency's ability to function," said Laura Haight, senior environmental associate for the New York Public Interest Research Group.

Cuts and More Cuts

According to the memo, the Department of Environmental Conservation may no longer be able to carry out the most basic of its functions.

The DEC had about 3,775 workers to start 2008; since then 260 staffers left under an early retirement program. and 150 more could soon be handed pink slips. Staffers from scientists in wildlife labs to office workers and site inspectors have left their jobs leaving the agency understaffed.

According to the unsigned memo, the DEC will not be able to properly staff cleanup sites, monitor natural gas drilling in the Marcellus Shale, make sure polluters keep up with state standards and manage wildlife at parks. Environmentalists say the crippling of the agency hurts business too.

"There will be huge delays in licensing. They (the DEC) aren't staffed to do permitting anymore," said Marcia Bystryn, executive director of the League of Conservation Voters. "Businesses need them before they can start projects, and in this financial climate, time is money -- the delay could kill development across the state."

Gallay agrees that the DEC's current situation could be bad for New Yorkers, the environment and business. "Industry wants a prompt response. Having low staff at the DEC hurts good businesses," he said. "The only people that benefit from lax regulation are bad businesses, and that hurts the businesses that are doing the right things. People think industry wants weak regulations. They don’t want weak, they want responsive, they want people to work with." According to Gallay, industry is going to have a hard time finding any sort of response from the DEC. Other environmental groups say that cleanup projects have been abandoned because the department doesn’t have enough staff to work on procuring project grants.

Firing Fallout

Grannis was perceived to be unafraid to speak out about what the cuts would mean for the state -- he is close to many legislators because of the years he spent as a member of the Assembly. Albany Assemblymember Jack McEneny called Grannis to tell him, "You are my hero" after the firing. Albany State Sen. Neil Breslin described Grannis as "the brightest person I know in state government."

Controversy over the firing still rages -- Grannis is so popular that legislators have been lead to speculate that his firing was part of the "dirty work" Paterson has undertaken as a favor for Andrew Cuomo to make things easier when the governor elect takes charge. They think Paterson is making unpopular moves for Cuomo because as a lame duck he has nothing left to lose.

Others openly wonder if Paterson fired Grannis or if the move was made independently by top Paterson aide Larry Schwartz. The Times Union, which first broke the DEC memo, reported that Schwartz phoned Grannis demanding he resign because the memo leaked. Grannis reportedly refused and demanded to speak to Paterson. Schwartz refused and then fired him. "Who exactly is running the state?" asked McEneny. "Schwartz or Paterson?" The Assembly plans hearings later this month.

Some activists and legislators want Cuomo to reappoint Grannis.

Leaving Superfund?

Beyond Grannis' firing and the cuts at the DEC, Paterson has proposed withdrawing New York from Superfund projects to clean up toxic sites. Discussing the cuts in a radio program on Oct. 28, Paterson said, "In DEC there will be job losses of approximately 150. This will cause us to reduce some of the services that we have. We’ll have to close a few educational programs, we will eliminate the state participation in Superfund. In other words where the federal government is conducting superfund activities, the state will not be involved."

The federal Environmental Protection Agency oversees Superfund projects across the nation, and whoever polluted the site is supposed to cover the cost, but the state pitches in 10 percent of the cost of the projects if the polluter can’t be found. In New York, state DEC staffers familiar with the cleanup area help the EPA adjust its plans to specific local concerns. No state in the union has ever withdrawn from the Superfund program.

Two long polluted sites in the city -- the Gowanus Canal and Newtown Creek -- are slated for clean up under the Superfund program. There are 114 Superfund sites in the state. What a state withdrawal would mean for these clean ups is unclear. An EPA spokesman said the agency had not received any proposal from the state and therefore could not speculate on what it would mean.

In fact, Paterson's proposal strikes some environmentalists and legislators as so outlandish that they do not take it completely seriously. "I'm not sure if it is a negotiating ploy, being used as a bargaining chip or what," said Bystryn. "I am certainly optimistic that they won't do this. We would be the first state in the nation."

But Gallay has a different take. "There is no sense in talking about bargaining chips when you have public health and safety at stake. These sites need funding. Some of these sites have been turned into recycling centers or receive other new investment after the cleanup. It helps the local economy. It is essential that the DEC stay involved. The feds have their plans and do a good job, but it is important to have the local office involved," he said.

As to how a withdrawl might work, Yancey Roy, spokesperson for the DEC, explained in an e-mail, "Typically speaking, EPA is the lead agency on federal [Superfund] sites and the state provides assistance/consultation. Often, this involves the state assigning a project manager to stay up to speed on the site, review test results and provide consultation, support and a state perspective. When warranted, DEC has assigned more than one person to a cleanup." In other words DEC staffers would no longer participate.

Gallay, who worked for the DEC, said that during his time there he saw how agency representatives from local offices familiar with the community near the site were able to help "get the right kind of cleanup for the community."

Laura Height of NYPIRG said that Paterson’s proposal flies in the face of logic. "Opting out of the superfund program makes no sense," she said. If the state needs money, she said it could apply for federal management assistance grants, such as the one it now has for the clean up of PCBs in the Hudson River But, she said, the state has not done this. "I don’t know if it is because they are short staffed or what," she added.

Looking Backward and Forward

Environmental advocates are united in their disdain for the way Paterson has dealt with the environment during the budget crisis, but they do not agree about what they can expect from the incoming Cuomo administration. Gallay estimates that most other agencies have faced about 8 percent cuts in their budgets; he said the DEC faces over 20 percent worth of cuts.

"During hard times we want a strong leader who can make smart, careful cuts. It is all going to hurt, but you want the cuts to be thoughtful. Paterson has not done that. He has made stupid cuts that have backfired on him," said Height.

Bystryn said she is ready to look ahead. "I'm not sure the environment was ever a major concern for Paterson, but Cuomo went to the trouble of putting together policy books which represent parts of an environmental agenda. He also went out of his way to seek our endorsement, and he didn't do that with everyone." Bystryn said she expects Cuomo will consult with her on the DEC budget come January.

"The state is nearly bankrupt, there are clearly going to be cuts, but we need to review each agency and find out what the core mission is and then make sure they are fully staffed to carry out that mission," she said. "I think the DEC's main mission is to protect New York's air, water and environment, and we need to make sure it is more than adequately staffed to do that."

Gallay said he has great hopes that the Cuomo administration will correct what he sees as Paterson's misdeeds. "All this governor has done is pour gas on the fire. I have every hope that Gov. Cuomo will administer his environmental agenda. He is a goal oriented man, and he published his environmental agenda, and he is not the kind of guy that wants to miss his goals. To meet them I think he will have to properly fund the DEC."

Cuomo’s Plans

Cuomo, though, has gone on the record supporting layoffs at the DEC. He has also taken an open stance on "hydrofracking" to extract natural gas from the Marcellus Shale. His "Cleaner, Greener NY" environmental agenda says he supports drilling, but only if it is safe. Environmentalists take that to mean that Cuomo would allow the drilling with DEC oversight, as well as with safeguards to insure the process will not pollute surrounding water supplies.

His statement also supports improving standards for the clean up of brownfields, partly contaminated former industrial sites, and backs tougher clean air standards. "The state is well served by enacting regulations to address climate change," the Cuomo campaign wrote. "Statutory standards provide certainty to industries and investment will follow." That again indicates to environmentalists that Cuomo supports staffing the agency that oversees polluters.

In its response to Cuomo"s "Cleaner, Greener NY," Environmental Advocates of New York praised a number of Cuomo's stances but its executive director, Rob Moore, closed with this:

"In the wake of the sudden dismissal of Department of Environmental Conservation Commissioner Pete Grannis on Oct. 21, â€Cleaner, Greener NY’ may underestimate the mess that the next governor inherits at the DEC and the state's other environmental agencies. ... Over the last few years, New York's environmental agencies have been decimated. Many aspects of the 'Cleaner, Greener NY' agenda will be impossible to implement without a significant re-investment in the agencies and an aggressive rebuilding effort. The success or failure of the Cuomo campaign's agenda depends on a commitment to rebuild these agencies."

Height said she does not want to wish anything tragic on New York, but she is concerned that. as the DEC becomes less effective, conditions are developing that could lead to real environmental disaster. "The BP oil spill happened when people were asleep at the switch," she said. "We know the agency is already too short staffed to monitor polluters, so we are trusting polluters to follow the rules, and that is dangerous when it comes to public health and safety."

Making 'Fair Share' Fairer

This is the second article in a series of commentaries Gotham Gazette will run between now and Election Day on the charter proposals appearing on the November ballot.

For decades, some low-income communities of color in New York have borne a disproportionate burden of polluting infrastructure. Communities such as Sunset Park, the South Bronx, East Williamsburg and Greenpoint are saddled with the bulk of the city's waste transfer stations, sewage treatment plants, bus depots and other facilities, both publicly and privately owned.

These communities are also the reluctant hosts of acres of brownfields and some of the busiest highways in the nation.

Clusters of pollution-spewing facilities have wreaked environmental havoc in these neighborhoods. They have been linked to disproportionate rates of severe health problems, such as off-the-charts childhood asthma rates and other cardio-pulmonary illnesses. As a result, organizations like UPROSE and El Puente in Brooklyn, Manhattan’s West Harlem-Morningside Heights Sanitation Coalition, and the South Bronx’s Nos Quedamos, The Point and Youth Ministries for Peace & Justice have spearheaded campaigns for environmental justice to challenge these noxious burdens and the ineffective public policies that put them there.

Until now, this struggle for environmental justice has been underscored by the failure of the City Charter policy called “fair share.”

In November, however, a new iteration of fair share will be on the ballot, and it is a proposal worthy of support. If approved, community districts overrun by private and public waste management and transportation facilities will begin to have a more complete picture of their environmental burdens.

A History of Unfairness

In 1989, neighborhood activists saw a glimmer of hope.

That year, the Charter Revision Commission added "fair share” criteria to the City Charter, making New York the first city in the nation to attempt to plan for the siting of city facilities in a more transparent and balanced manner.

Fair share encourages a more equitable distribution of city facilities. According to the charter, agencies are required to analyze a community district's share of city facilities, like sanitation garages or sewage treatment plants, before siting, expanding, closing or reducing a facility. The city also is required to provide annual notice of its facility plans to local community boards before making final decisions. The Department of City Planning also must publish the Atlas of City-owned Properties and its accompanying map, which identifies the location of all city facilities by address and block and lot number.

The charter allows community boards to hold hearings and -- along with borough presidents -- propose alternative sites before city agencies reach a final siting decision. This unprecedented level of transparency was supposed to give overburdened communities additional tools and a platform for both agencies and the public to strive for greater fairness.

These provisions are advisory, so they were not designed to tie an agency's hands. Rather, they were intended to help agencies plan better, increase transparency and allow affected communities a voice in the process.

However, fair share hasn't produced greater fairness or useful transparency.

Chief among fair share’s problems is that the Atlas of City-owned Properties and accompanying map only include city facilities. Of course, not only facilities owned and operated by the city have environmental impacts. The question presented to voters in November, as part of Question 2 on the City Charter, would begin to resolve this by including all public and private waste management and transportation facilities that overburden communities on the city map.

Polluting facilities operated by the state, public authorities and the private sector also undermine our local air quality. For example, some of the worst environmental impacts to local air quality and road infrastructure in East Williamsburg, Greenpoint and the South Bronx were generated by dozens of private waste transfer stations handling the city's solid waste. Presently these facilities are left off of the city atlas and map. This proposal would change that.

Under the current system, fair share rules require agency planners to look only at private waste management facilities within a 400-foot radius of a proposed "local" city facility or within a 10-block radius of a proposed "regional" city facility. As a result, any private or public facility beyond the 400-foot radius -- about half the length of an average city block -- does not appear on any map or analysis of a proposed local city facility. With city agency planners only looking within arbitrary areas with no scientific, medical or engineering basis, the entire pollution picture is left largely unexamined.

Fairness in a New Era

The limitations of the city’s fair share policy is even more apparent in the 2002 New York City Waterfront Revitalization Program. The program actually encourages the concentration and clustering of industrial and maritime activities in six areas called "Significant Maritime and Industrial Areas." These designations are found in communities of color like Sunset Park, Red Hook, Brooklyn Navy Yard, Newtown Creek, the South Bronx and Staten Island's North Shore.

Development applications in these districts must meet fewer review standards than those for other waterfront areas, thereby easing the siting and clustering of polluting infrastructure. Moreover, all of these areas are in storm surge zones. Given the concentration of industrial materials and uses in these districts, any significant storm surge could expose local residents and workers to hazardous materials and contaminate waters and adjacent land with dangerous chemicals, heavy metals or other hazardous substances.

These issues loom large for the city's environmental justice communities, many of which are waterfront communities whose residents have advocated for maritime and industrial area reform.

If our city map had adequately included all city, state, federal and private facilities in each community district, officials might have reconsidered clustering even more industry in these areas.

Closing the Loopholes

The NYC Environmental Justice Alliance, our members and some allies proposed multiple amendments to the 2010 Charter Revision Commission to address the loopholes in the city’s fair share review process.

For example, the alliance proposed that power plants and other public and private infrastructure be added to the atlas and accompanying map. Given the technological advances since 1989, we also proposed that the city include environmental and public health data for each community district -- data that is already collected by the departments of health and environmental protection, but not shared in one centralized, public and easily accessible location. Why not put all this relevant data in the atlas and map? (For more, please read our testimony on our website.)

In the end, the commission only agreed to mandate the inclusion of all state, federal and private facilities that handle solid waste and transportation in the city facilities map.

Our advocacy campaign was undermined by several factors. Some good government and social justice allies politically miscalculated that the mayor would re-empanel another commission after 2010, and therefore urged commissioners to “go slow/get it right." Still other allies -- and some elected officials -- were single-issue advocates concerned only with term limits or nonpartisan elections, and urged the commission to do nothing at all.

The commission itself repeatedly insisted it would not take on sweeping overhauls, given its short time frame.

Thankfully, several commissioners understood the value and fairness of what environmental justice activists and our allies proposed and advocated on our behalf.

While the 2010 commission left many proposals off the table, the expansion of the city's map reflects a much-needed first step in overhauling fair share. By voting yes on the map for facility siting question, New Yorkers will finally begin to see how truly overburdened some communities are -- and demand that something be done to correct this environmental injustice.

Eddie Bautista is the executive director of the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance.

Tackling Fracking

Photo (cc) Helen Slottje

A natural gas drilling site in Pennsylvania.

The Paterson administration saw it coming -- the economic collapse, state budget deficits growing to unprecedented proportions. "In a budget crisis we look for a pot of gold," said Susan Lerner, director of Common Cause NY.

The Paterson administration's pot, though, holds not gold, but natural gas.With New York home to large natural gas reserves, some project that tapping into the gas stored in the Marcellus Shale formations in the Southern Tier and around the New York City watershed could generate $1.5 billion in revenue for the state by 2015. The drilling could bring jobs to the state's impoverished towns and boost their economies.Gaining access to that gas would require a more powerful version of a method used to extract the gas by blasting millions of gallons of water into wells.

Despite the possible economic benefits, the plan to extract natural gas in New York has attracted opponents, who claim the environmental risks of the method that would be needed to extract gas from the Marcellus Shale far outweigh any financial and economic benefits. They fear the chemicals used in the hydrofracking process or the gas itself could pollute local water supplies. Hydrofracking is not new. Natural gas wells across the state have used the process--just not with the power and amount of water and chemicals that would be needed to extract in the Marcellus Shale.

While some legislators seek to halt the drilling, questions of if and how to extract the state's natural gas rest with the Department of Environmental Conservation. That agency could delay any action until a new administration takes over in January.

Getting the Gas Out

The key issue in the debate revolves around hydraulic fracturing, or hydrofracking, as it has become known. This process used to harvest natural gas from the earth involves blasting millions of gallons of high pressure water and chemicals into holes drilled in the ground. Companies like Chesapeake Energy Corp. were ready and willing to use the process to tap the state's gas.

Citing what they say is widespread environmental damage in the West, environmentalists and others say the chemicals could make the water dangerous to drink and produce toxic runoff .

In 2008 Gov. David Paterson signed a bill designed to streamline the permitting process to allow companies to drill. He also ordered the Department of Environmental Conservation to update its generic environmental impact statement, a document that would set the standards for hydrofracking across the state. Lerner said she would describe the normally environmentally conscious Paterson administration as "bullish" on fracking.

It wasn't long before environmentalists and city officials were decrying the dangers of drilling anywhere near the city's watershed. They charged the process could contaminate the water -- at best, necessitating expensive filtration systems, at worst making it undrinkable.

After a great outcry from the city and concerns expressed by the Obama administration, Chesapeake Energy Corp., the only gas company that owns a lease on land near the city's watershed, promised it would not drill on the land. While the promise reassured some, it did not mean drilling would never take place there. Other companies, not bound by Chesapeake's pledge, could acquire leases. Natural gas prices are currently low, and there are many other less controversial places to find it. That, of course, could change.

In April the department announced that the generic environmental impact statement would not apply to drilling in the New York City and Syracuse watersheds, and instead applications for wells in those areas would be considered on an individual basis. This means companies would have to undergo rigorous review for each well they proposed to drill, including public hearings. Opponents of fracking saw this as a reprieve for the watershed since getting individual permits could be costly and cumbersome. And the review process would give the opposition a chance to fight every well.

This, too, though did not mean there never would be drilling in the city's watershed, and it did not apply to drilling in other parts of the state.

The process of setting conditions for using hydrofracking in upstate New York continued. The Department of Environmental Conservation has issued its draft supplemental generic environmental impact statement, laying out the basics of the final statement for public review.

Meanwhile, the department continues to review public comments made about the draft generic environmental impact statement. The agency has said it will present a complete statement, but it is unclear when. The deadline has been changed from this fall to actually, there is no deadline, according to a spokesman.

Opponents of fracking are cautiously optimistic about this. They worry that the draft environmental impact statement does not fully protect surrounding water supplies and does not get New York the best deal for its natural gas. They do say that New York would require more of companies than a lot of states. Among other things, New York, unlike other states, would compel companies to reveal the chemicals they plan to pump into the ground during fracking.

A number of advocates hope the statement won't be issued until the new administration takes office.

"We are hopeful that if the decision is put off until a new administration can weigh in then reason will prevail," said Kate Sinding of the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Assembyman Robert Sweeney, chair of the Assembly’s Committee on Environmental Conservation, is sponsoring a bill that would place a moratorium on hydrofracking. "One of the reasons I want to pass the moratorium is that I want to give the incoming administration a chance to weigh in. I don't want to see a rush of permits in December and a new administration taking over in January and being stuck with it," he said.

The State Senate has already passed a moratorium.

The Promise

So what is the natural gas industry promising? At the most basic level, the state takes in fees for well permits according to the depth of the wells. Hydrofracking usually involves wells that range from 5,000 to 20,000 feet. The standard fee for a well of over 10,000 feet is $3,8000 plus $190 for each additional 500-feet of depth.

Brad Gill of the , a trade association founded in 1980, lists the financial rewards he sees for the state.

"Citizens benefit through lease revenues that are up to thousands of dollars an acre. Some have already earned a million dollars. I can just see the new John Deeres or kids going to college," he said.

If the land is owned by the county or state, the governmental entity benefits from lease payments. "Then there are the tax revenues," he said. "Right now the state makes over $10 million to $12 million a year in taxes on revenues created from drilling, but the general impact to the state could be over a billion dollars. There is also revenue to the state through jobs, new construction of buildings and people being hired.”

A study by Natural Resource Economics, Inc., projected that revenue from drilling could reach $1.5 billion by 2015.

Sweeney, though, said that money may not turn out to be the windfall some expect. "In Arkansas," he said, "the state has spent more money on repairing the roads damaged by the trucks and machinery required for the process than the state has made from taxes from drilling."

In the meantime, Sweeney said said he's still "hearing from people on both sides of the issue. But some people just see dollar signs, and I don't just mean the companies. I hear from Long Island residents who own property upstate and see opportunity in this."

The Promise of Jobs

Gill said that the state should not delay a decision forever. "People say to me 'the oil will be there.' Well it will, but jobs won't. They really won't," said Gill. "There are companies that are leaving and building out in Pennsylvania."

He cites , a company he says has moved "half their workforce" that was in New York out of state.

But some wonder how many and what kinds of jobs drilling operations would create.

"It is a boom-bust cycle," said Lerner. "Like the gold rush, the towns get a temporary economic boon." She says the workforce "is a group of roving energy professionals that live in motels and then move on. It is not the economic boon to these places it is thought to be."

Sweeney agrees. "They call them man camps in Colorado. They are surrounded by barbed wire. They keep the workers fenced in to stop problems between them and the locals," he said.

Gill says some traveling professionals are hired, but drilling does create significant numbers of local jobs. "We have contracts with some highly skilled workers, but we also create local jobs. We have a company with 70 percent local and 30 percent out of town," he said.

Battle for Hearts and Minds

Both sides in the dispute are fighting hard to win over public opinion -- and the state government. For the natural gas companies, Lerner said that means spending millions of dollars to counter the public outcry.

In June, Common Cause NY study that looked at how much money the natural gas industry is pouring into its campaign to get approval for hydrofracking. A similar Common Cause study in Pennsylvania had showed a striking relationship between campaign donations from the natural gas industry and well approvals. The New York study found the natural gas industry is spending its money in a different way here.

Since 2005 the companies have spent $2 million on lobbying -- most of money in the last two years. Lerner said that a good portion of recent expenditures have gone to buy advertising as the natural gas companies try to win over voters with the promise of financial benefits. Lerner said that, in some ways, those buys could be considered campaign expenditures, because the ads are airing during the campaign season.

"There has not been as much spent on campaign contributions -- not the level spent in Pennsylvania -- but the advertising is going on during the election season, and it may be a bleed-over," said Lerner.

Gill disputes that his industry has spent much on lobbying or advertising. In fact, he said, he thinks the anti-fracking movement is winning the battle for hearts and minds. "I think we are losing the battle for public opinion. I hate to admit it, but we are. I've always said emotion will win out over science and reason, much to my chagrin."

One indication of where public sentiment lies could be the fact that the Working Families Party, a pro-labor group, has created a campaign to support a moratorium on fracking. "I think that on one level you think, this is an environmental issue, so why is the WFP getting involved," said WFP spokesman Dan Levitan. “The hydrofracking fight is about corporate power vs. democratic power. It is about how far corporate power goes. We heard from our own members, who asked us to get into this."

And Levitan points out that the issue matters to people across the state. "There are few issues that traverse the great expanse of this state, but everyone drinks water, so this does."

We Wait

So now the natural gas industry and opponents of fracking wait for the Department of Environmental Conservation to provide its final draft generic environmental impact statement. In the meantime, the Assembly could convene as expected in November and pass the moratorium already passed by the Senate. Gill said he has been discussing the measure with the Assembly to point out what he calls flaws in the Senate bill. For example, he said, as currently written, the bill would ban shallow drilling that does not involve fracking, which has generally been accepted as safer than hydrofracking and has been going on in the state for decades.

"The way the Senate bill is written it would decimate the existing industry," said Gill. "More jobs lost -- but I’m sure they didn’t intend it that way." When asked how he would like to see things progress, Gill said although he sees the draft generic environmental impact statement as "a heavy hammer over the industry" and "a hard pill to swallow," he would like to see it enacted this fall.

In that case, "absent any litigation, drilling would begin this spring," Gill said. But he isn’t holding his breath.

The possible new state bosses have weighed in to some extent. Anti-fracking advocates are concerned that Democratic gubernatorial candidate Andrew Cuomo is amenable to the natural gas industry and targeted him with petitions and protests. Gill said he has high hopes for Cuomo because he understands both "the safety concerns and the impact it would have on the economy of western New York."

It is expected his opponent, Carl Paladino, would be in favor of fewer restrictions, although his campaign did not respond to calls for comment.

In a written response, the campaign of the Democratic candidate for attorney general, State Sen. Eric Schneiderman, said, "Neither the state nor the federal government has determined that hydrofracking is a safe practice, and Eric will sue to make sure that no drilling takes place until it is." The campaign of Republican candidate for attorney general, Staten Island District Attorney Daniel Donovan, did not respond to requests for comment.

Stated Meeting: Green Light!

Photo (cc) Gilderic

Shining a light on electricity usage, the City Council approved a package of legislation Wednesday that aims to increase efficiency, including a bill requiring commercial properties to use light sensors.

The bills all update the city's building code to incorporate and emphasize green building practices.

In addition, the council approved legislation to siphon off spaces in garages for shared vehicles, like Zipcar.

Green lights

The product of a green code task force convened by Council Speaker Christine Quinn and the Bloomberg administration, the legislative package is one of many steps to come that will force city buildings to use less energy, Quinn said.

"This package of legislation is turning the lights off on wasteful lighting," said Quinn.

One piece of the measures (Intro 266) would require commercial properties install sensors in small office spaces that would detect whether the room was occupied. The sensor would subsequently shut off the lights if it were vacant for more than 30 minutes. The bill does not take effect until January.

Office spaces with less than 200 square feet, break rooms and classrooms would all have to have sensors under the bill.

The council also approved legislation (Intros 262-A and 277-A) to allow occupant sensors and photosensors, which measure the amount of natural light in the area, in residential buildings, such as hallways or stairways, and in public areas of commercial buildings, like entrances. It would allow building owners to install energy efficient lighting, like motion sensors, in these areas as long as it would not present a safety hazard.

The final two bills modify the building code to force new projects to consider energy efficient standards (Intro 267-A) and revise the minimum lighting standards to use foot-candles instead of watts. Foot-candles measure luminosity, while the watt is a measure of power.

Car Share Spaces

The council wants to save a space for car shares.

It unanimously passed legislation to set aside space for car share programs in garages across the city to make the service more accessible to their growing membership.

A third of the total car-sharing members nationwide are within the five boroughs, according to the council. That membership increased by 50 percent in 2008 to 279,174 people.

The legislation approved Wednesday would not only ensure spaces are available in garages but it would also, for the first time, regulate where these vehicles are parked. It prohibits parking on residential streets, council officials said.

The bill allows car share vehicles to park in up to 40 percent of spaces in public garages, 20 percent in medium to high density residential garages and 10 percent in a lower density residential districts as well as commercial, community or manufacturing garages.

Another Natural Gas Controversy

Photo (cc) Voxphoto

While New Yorkers hotly debate the safety of hydraulic fracturing, a controversial method for extracting natural gas from upstate rock formations, a second natural gas issue has quietly started to simmer.

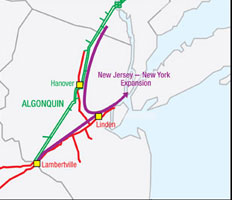

Houston-based Spectra Energy filed a preliminary federal application to construct approximately 20 miles of new natural gas pipeline across northern Staten Island and southwestern New Jersey, under the Hudson River and into Manhattan's trendy meatpacking district where it will connect to Con Edison lines around Gansevoort Street and the West Side Highway.

The project will expand and diversify an existing natural gas pipeline system between Staten Island and New Jersey. According to a Con Edison spokesperson, Chris Olert, the expansion will help meet growing customer demand for natural gas and improve the reliability of gas delivery. Currently, Con Edison delivers 225 billion cubic feet of natural gas a year to residential and commercial buildings. New pipelines will increase that capacity by 8 million cubic feet per day. In addition, Spectra estimates the project will create 100 new construction jobs when it launches in 2012 and 500 in 2013, when it goes online.

However, some communities along the new pipeline route, which include Staten Island's North Shore, Bayonne, Jersey City and Manhattan's West Village, have rallied to protest the project. In early August, the debate came to a head at a series of public scoping meetings held by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the primary federal agency regulating the project. Although attendance at the meetings was sometimes sparse, emotions surrounding the project were explosive.

"We don't want people or nature getting blown up," said Beryl Thurman, president of the North Shore Waterfront Conservancy of Staten Island.

Safety Concerns

Although natural gas explosions are relatively rare (the US Department of Transportation reported only 47 serious incidents across all US pipeline systems in 2009), they can be dangerous. Project opponents point out that just this summer, natural gas leaks led to explosions and deaths in Michigan, Texas and South Los Angeles. Closer to home, last February, a natural gas explosion in Middletown, Connecticut killed five people and in 1994 a natural gas pipeline ruptured in Edison, New Jersey, causing damage in excess of $25 million.

None of those places were as densely populated as these areas in New York and New Jersey. "Natural gas simply does not belong stored in an urban setting," stated Jersey City school superintendant, Charles Epps, pointing out that at least six schools sit within three blocks of the pipeline route. In addition, parts of the pipeline route come very close to the heavily trafficked New Jersey Turnpike, Holland Tunnel, and PATH Trains. The proposed line would also cross the West Side Highway.

These areas are as crowded with industries as they are with people. Fuel tanks line the Bayonne shore. Jersey City's Tropicana Plant, which includes a containment vessel for anhydrous ammonia -- a highly volatile gas --, is adjacent to the proposed pipeline route. This January, the federal Environmental Protection Agency designated Staten Island's North Shore one of the nation's ten "environmental justice showcase communities" because it houses at least 21 chemically contaminated sites all located within 70 feet of residential properties. Critics worry that project construction will release those contaminants and that various chemical combinations will make natural gas leaks more volatile and explosive.

Image from Spectra Energy

The pipelines' marine routes are equally contaminated from scores of petroleum, chemical and manufacturing plants that historically lined their shores. In a letter to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, New York/New Jersey Baykeeper attorney Chris Len expressed concern that "the pipeline [could] impact ecological resources already stressed past any reasonable limit by centuries of industrial development."

Responding to such fears, Spectra spokesperson Marylee Hanley said, "The pipeline will be built to exceed highest safety standards set by federal government." She also explained to the Staten Island Advance that pipelines are monitored continuously for leaks and pressure loss by meter stations. Valves can be closed by remote and inspectors physically check the land surrounding the pipelines three times a week. The pipes themselves would be buried up to 30 to 40 feet below ground, added Spectra Project Manager Ed Gonzalez.

But critics question Spectra's safety record. In April, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection fined one of the company's joint ventures $22,000 for two unpermitted oil discharges and for delaying notifying the state of the incidents. In 2004, an underground storage facility operated by Duke Energy (from which Spectra spun off in 2007) exploded in Moss Bluff, Texas, causing an emergency evacuation and over four days of fires with flames that exceeded 1,000 feet.

Competing for Space

Part of the problem is that in dense urban areas, pipelines vie for space with other infrastructure. Last month, the New York City Department of Environmental Protection expressed concerns that the pipeline would have serious impacts on water and sewer lines along its routes in both Manhattan and Staten Island. In a January letter to U.S. Senator Robert Menendez, Jersey City Mayor Jerramiah Healy argued the pipeline would complicate city's ongoing efforts to service its aging water and sewer infrastructure.

On Staten Island's North Shore, which has the borough's highest asthma rates, proposed project construction would re-route heavy truck traffic from Richmond Avenue to residential streets. Traffic effects are less clear where the pipeline crosses the West Side Highway, but at this month's scoping meeting, Gonzalez promised to "minimize traffic interruption."

Gonzalez also promised to work closely with nearby construction projects, which continue to proliferate in the far west village. On Gansevoort, for instance, about a block from where the pipeline will connect to Con Edison, the new Whitney Museum is scheduled to break ground in May 2011. In addition, the pipeline will enter Manhattan via the Gansevoort Peninsula, where the Hudson River Park Trust plans to build baseball fields, batting cages, and a play lawn over the next several years. But park trust Vice President for Marketing David Katz remained sanguine about the park's new neighbor, "We are working with [Spectra] to make sure the project does not impact current and future park plans," said Katz.

The Need for Jobs

For pipeline supporters the energy options, tax revenues and jobs it will produce balance out much of the concern. At the scoping meetings, Gonzalez estimated the project would generate $10 million in tax revenues in addition to hundreds of jobs. But residents of Staten Island's North Shore, which has the borough's median lowest income and highest unemployment rate, remained doubtful that project jobs would directly benefit them. "These are union, skilled labor jobs. If you don't have a union book, you're not getting out there doing that work," said Dixon.

In his January letter, Mayor Healy argued that neither jobs nor tax revenues outweigh the project's potential to limit residential and commercial development. According to Healy, because the project requires laying pipelines under privately owned land and given the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission's historic support for eminent domain would lower property values and inhibit investment. The Lefrak Organization, one of the city's largest developers, supported this claim. At Jersey City's scoping meeting a representative testified that some potential commercial tenants have already backed off after hearing about the pipeline.

Just before the scoping meetings Lefrak, Healy and others joined NY/NJ Baykeeper in calling for an extension to the August 20 public comment deadline. Considering the complex issues involved, NYNJ BayKeeper's Len called the four-week timeline "startlingly short. "Moreover, Len argued that many constituents directly affected by the project do not speak English and others were on vacation.

The Bayonne meeting drew more than 100 people and in Jersey City nearly 300 residents and public officials attended. But only approximately 10 to 15 people showed up in Staten Island, where the meeting coincided with the popular "National Night Out Against Crime." In Manhattan, one of the few residents present commented, "holding a meeting in August is a slap in the face to Manhattanites."

On the west side of Manhattan, Community Board 2 announced last week it would hold a public hearing with representatives from Spectra, Con Edison and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in October.

A Federal Energy Regulatory Commission spokesperson confirmed that it will accept comments by phone, mail and email until Spectra submits its formal application, which they project for December. Until then, Spectra stated that it would continue to adjust its route and respond to public input. For instance, just before the scoping meetings, they announced that they were considering moving the pipeline from Staten Island's heavily trafficked Richmond Terrace into the water around Shooters Island -- a World War I shipyard turned bird sanctuary.

Once it receives the formal application, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission will hold another round of public hearings before it issues an environmental impact statement. Looking forward to that period, Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer issued a statement urging FERC to use "plain English "in explaining the impacts of the project. Stringer's office also offered to assist the commission in its public outreach efforts.

In the meantime, natural gas continues to be a pressing issue. Earlier this month, the New York State Senate approved a one-year moratorium on hydraulic fracturing (the state Assembly and Governor David Paterson are expected to follow suit). The new pipelines do not depend on that decision -- they will receive natural gas from the southeastern U.S. and Canada, as well as those parts of the Marcellus Shale in West Virginia and Pennsylvania, where hydraulic fracturing is expanding. Spectra has diverse interests in the shale. The company owns half of DCP Midstream Partners, a natural gas processor. DCP recently entered a joint venture with EQT Corp., Appalachia's largest natural gas exploration and production company to pursue natural gas opportunities in the Marcellus Shale upstate and the Huron Shale in extreme Southeast Ohio, West Virginia, and Northeast Kentucky.

The pipeline's links to upstate drilling are what alerted some people like Manhattan resident Wendy Byrne to its existence. Byrne said she has opposed hydraulic fracturing for some time and was concerned about the amount of methane released by natural gas.

For Staten Island's Thurman, challenging the Spectra pipeline represents solidarity with communities in Pennsylvania, who claim that hydraulic fracturing has destroyed their water supplies. "We're trying to get people to stop thinking in terms of â€just put it anywhere, just not near me,'" she said.

As City's Temperature Rises, Air Quality Falls

Photo by Jorge Castro

It has been a great summer for anybody who sells ices on the street, repairs air conditioners, or enjoys a run through a park sprinkler. For New Yorkers who sweat their way through the hot days, though, it’s been struggle since the start of spring. That is because, this year, New Yorkers have lived through the hottest spring and summer on record. From March to June, we saw four consecutive months that broke their all-time record for average monthly temperature, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

And July came close, only avoiding the mark thanks to an unseasonably cool final day that dropped the average monthly temperature in the city to 81.3 degrees, just one-tenth of a degree cooler than July 1999, the reigning hottest July on record.

Weather reporters tend to focus on the temperature readings, but hot weather also brings spikes in levels of ground-level ozone, more commonly referred to as smog. That's because ground-level ozone forms when volatile organic compounds (mostly hydrocarbons) and nitrogen oxide gases mix in sunlight. When there is more sunlight and temperatures rise higher and higher, the ozone reaction speeds up, creating more and more ozone. (By the way, ground-level ozone is different than stratospheric ozone, which helps shield the Earth from dangerous sun ultraviolet rays).

Unhealthy Air

Breathing too much ozone can trigger or worsen a wide range of serious health problems in the short term, including asthma emergencies, bronchitis and emphysema. For some people, inhaling high levels of ozone can lead to chest pain, wheezing, throat irritation, and congestion. Over the longer term, repeatedly breathing the levels of smog we have in New York City can reduce lung function and permanently scar lung tissue.

Children, the elderly, people with lung disease and people who work or exercise outdoors are all at greater risk than the general population.

New York City has never met the federal health standards for ground-level ozone. These standards are set periodically by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and are designed to protect both public health and public welfare (crops and vegetation, for example). The federal government sets two ozone standards -- the "one-hour" standard is designed to protect people from short-term spikes in ozone levels, and the "eight-hour" standard is intended to protect us from more chronic exposure to ozone.

Certainly, cars, trucks and industrial pollution sources are cleaner than they were 40 years ago when the first Clean Air Act was passed. But as our understanding of the health impacts of ozone has increased, the health standards set by the U.S. EPA have become more stringent.

The agency’s AirNow website includes a public awareness program that informs the public about pollution levels in real time and provides daily forecasts of expected pollution levels and historic information about past pollution levels. On the website, the EPA index system rates ozone -- and particulate matter as well -- from a scale of 1 to 500. An Air Quality Index value of 100 generally corresponds to the national health standard for the pollutant. An Air Quality Index rating of 50 is considered to be "good" air quality that has little potential to affect public health. At 300, the agency considers the air to be "hazardous" to breathe -- so polluted that everybody is at risk and serious enough to trigger public warnings about emergency conditions. In other words, when the Air Quality Index is below 100, EPA believes that the air is generally clean enough for all New Yorkers.

EPA declares an Air Quality Alert day whenever Air Quality Index levels of ozone or particulate pollution exceed 100. When the Air Quality Index is between 101 and 150, EPA considers the air to be "unhealthy for sensitive groups." Although the health of the general public is not expected to be affected in this range, people with lung disease, older adults and children are at a greater risk from exposure to ozone, while particulates in the air pose a greater hazard to persons with heart and lung disease, older adults and children. People in these risk categories are advised to avoid prolonged outdoor exertion when the index is above 100.

Thanks to this summer's repeated heat waves, the number of Air Quality Alert days has skyrocketed in 2010. Indeed, according to EPA, there have been 27 Air Quality Alert days since Memorial Day. All but one of these Air Quality Alert days were in the 101 to 150 Air Quality Index range. On July 6, however, portions of the city moved into the red zone of "unhealthy" as everybody could begin to feel some adverse effects of the high air pollution. In a normal year, there are fewer than five Air Quality Alert days in the city during May, June and July.

As Michael Seilback of the American Lung Association in New York said, “For the hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers who suffer from asthma and other lung disease, these high levels of ozone could make it difficult to breathe and could even lead to hospitalizations or death.”

Cleaning Up Summer

New Yorkers who are concerned about the potential health impacts of breathing high levels of ground-level ozone should avoid prolonged outdoor exertions when the heat and pollution levels are high.

It is easy for concerned New Yorkers to keep up to date with the air pollution levels and forecasts in their community. By subscribing to EnviroFlash, New Yorkers can get a free daily email with up-to-date pollution information for their ZIP code. Calling the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation's air quality hotline at 800 535-1345 also will provide localized air quality information.

On Air Quality Alert days, New Yorkers can help reduce the city's pollution levels by avoiding unnecessary car trips, using transit and reducing electricity consumption wherever possible.

Hot summer days are also a good time to remind ourselves of the policy steps that our elected leaders and government officials can take to reduce summertime ozone levels in years to come. In Washington, EPA is expected to announce its new national eight-hour standard for ozone by the end of August. The agency is considering a range of ozone levels below the current standard, and setting the most stringent standard will be especially important. That is because the new standard will trigger revised state-level requirements to develop additional programs to reduce pollution levels to meet the new standard.

If we are ever to escape from the trends of ever-hotter and more-polluted summers, it will be critical for Washington to take positive action on these necessary policy steps, and for New York to adopt a plan to finally meet EPA’s health standards for ozone, once and for all.

Rich Kassel is a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, where he focuses on urban air pollution and transportation issues. He also chairs the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, a regional transportation advocacy organization; is on the board of the New York League of Conservation Votes and blogs on a variety of environmental issues on the NRDC Switchboard.

Stated Meeting: Council Moves to Increase Recycling

Photo by Ianqui i

With many city residents still dumping all their trash in the garbage can, the City Council yesterday passed 11 bills to spur recycling in the city, including a measure that would let New Yorkers put all rigid plastic containers -- even yogurt cups -- in the blue bin.

In another action aimed at improving the environment, the council passed a bill to reduce pollution from the burning of heating oil in the city. And during its first meeting at 51 Chambers Street, where it will convene as City Hall undergoes repairs, the council also gave its final OK to two long-debated development projects -- one at the old Domino refinery on the Brooklyn waterfront and the other in Flushing.

In general, City Council Speaker Christine Quinn said, the meeting focused on created a green and growing city.

Revving Up Recycling

In the 20 years since it passed its first residential recycling bill, New York has failed to meet its own goals and fallen behind other cities in the country, according to most experts. While the city had hoped to recycle 35 percent of its garbage by 2007, figures released earlier this year found only 25 percent of trash was being recycled citywide.

All the garbage not being recycled, said, has to go to far-away landfills, forcing the city to pay shipping and dumping fees. This, said Letitia James, chair of the council sanitation committee, "puts an unsustainable burden on our city's economy."

Boosting recycling on the other hand, James said, will mean "more work for local vendors and more money saved in city coffers."

Of the bills only the one on yard waste -- Intro 157 -- encountered any opposition. The measure would require homeowners to separate and bundle grass clippings and the like for collection and eventual composting at city housing authority facilities.

Several members argued this would place a burden on homeowners who, they said, already are suffering from higher taxes and water bills and reduced city services.

"The city of Ne York is taking a perfectly biodegradable product -- grass clippings -- and suggesting you can't put it out with your garbage," said Republican Daniel Halloran of Queens. "It's another jab at the outer boroughs and homeowners."

Responding, Councilmember Erik Martin Dilan said the bill would not prevent anyone form cutting their lawn but simply require them to put the clippings out for collection at an appropriate time."

Also voting no were Councilmembers Vincent Ignizio, Peter Koo, Eric Ulrich, James Vacca, Peter Vallone, Mark Weprin and James Oddo.

Some aspects of the package intend to make recycling more convenient, such as Intro 148-A, which would expand plastic recycling. Currently the city accepts only some types of plastic for recycling, taking milk jugs, for example, but not yogurt containers. This bill would require the sanitation department to recycle all rigid containers following the opening a recycling facility in Brooklyn now slated to begin operations in 2012.

"The biggest thing that's holding New Yorkers back from recycling is confusion, Quinn said, noting that people now have to search for a small number on a plastic container and then check to see if the type of plastic is indeed fit for recycling.

In further efforts to make recycling easier, Intro 158 would increase the number of recycling bins in public spaces from the current 300 to 700 within the next 10 years and require the sanitation department to start a recycling and reuse program for textiles as well as recycling programs for batteries and tires. The bills would also educate the public about recycling by creating and distributing a guide on the residential program and requires the sanitation department to hold workshops on recycling for owners and employees of apartment buildings that have received fines for repeated violations of the law (Intro 147A)

Other provision address hazardous waste. Under Intro 162 the Department of Sanitation would have to hold at least one hazard waste collection event in each borough every year, while Intro 142-A calls for a voluntary program in which manufacturers and retailers would take back unused paint, which, according to the council, accounts for about half the city's total of hazardous household waste.

The package also looks at expanding recycling beyond the home. Intro 165-A seeks to boost it at public and private schools by designating a recycling coordinator in schools and providing recycling bins, while Intro 156-A targets city agencies.

And the package calls for a lot more studies including ones on composting of food waste (Intro 171-A) and commercial recycling (Intro 141-A).

All the measures except the one dealing with yard waste passed by a vote of 45 to 0.

Cleaner Heating

With heating oil accounting for a large portion of New York's soot pollution -- more than all the vehicles on city streets -- the council unanimously approved a measure it says will clean the air and in the process reduce the city's high rate of asthma.

The bill, Intro 194-A, sponsored by Councilmember James Gennaro, would reduce the maximum level of sulfur allowed in No. 4 heating oil, one of the dirtiest grades, by half. It also quires all heating oil burned in the city after Oct. 1, 2012 contain about 2 percent biodiesel. That biodiesel, said Gennaro, comes "from what I like to call New York's crop, which is restaurant grease."

The 2 percent of regular heating oil saved, he said, would be equivalent to a seven-foot-deep lake covering City Hall Park.

Domino Done

After six years of debate and negotiations, the council unanimously approved an 11-acre housing and retail project on the site of the old Domino sugar refinery in Brooklyn. The current plan calls for 2,200 apartments there, with 660 designated as affordable. The project also includes community space that would allow for the building of a new elementary school if necessary.

The plan, which has had the enthusiastic backing of Bloomberg administration, was altered somewhat in response to concerns by Stephen Levin, the area's council member who initially opposed the plan on the grounds that it was too big and would not include enough affordable homes. Following negotiations, the developer, Community Preservation Corp. reduced the height of the buildings, but did not add more moderately priced apartments.

Flushing Commons

The council's vote to approve Flushing Commons also ends an extensive negotiation. This project would create residential, retail commercial and community space -- along with more parking spaces -- on the site of a municipal parking lot Flushing. Of the 760 apartments, about 140 will be affordable.

Small-business owners in the area, many of whom are Korean, feared they would not survive construction and worried they would be pushed aside by Chinese-owned businesses now located elsewhere in the bustling Flushing area.

To try to allay the small-business owners concerns, earlier this week, the Bloomberg administration announced it would provide $6 million to local merchants. The businesses owners originally were slated for $2.25 million in aid.

The money would go for loan guarantees, signs and various businesses services with half of it aimed at alleviating parking problems in the area during construction.

Council members hailed Flushing Councilmember Koo for his efforts in addressing the small-business owners' concerns.

The project was approved 43 to 2, with Councilmembers Gale Brewer and Brad Lander voting no.

Wind Project Off Rockaway Could Help Power New York's Future

The Middelgruden wind farm off Denmark's coast has been supplying Copenhagen with energy since 2000. Now efforts are underway to bring offshore wind famrs to the East Coast, including New York.

Since April, New Yorkers have watched two environmental disasters in two different parts of the country with sadness and horror. On April 5, an accident at the Upper Big Branch coal mine in West Virginia killed 29 people. And, on April 20, 11 people died in the Deepwater Horizon explosion -- a disaster that has sent as much oil spewing into the Gulf of Mexico every four to five days as was spilled in the Exxon Valdez accident of 1989. Both these events provide potent reminders of the dangers and risks of our addiction to fossil fuels to power our vehicles, homes and businesses. If New York needed a wake-up call for cleaner energy sources, these two accidents should ring our alarms loudly and clearly.

Amid this flood of disastrous environmental news, one piece of progress was reported on April 28. On that date, the U.S. Department of Interior approved the first-ever, utility-scale offshore wind energy project -- the Cape Wind project in Nantucket Sound -- after a nine-year federal review process. This process lasted longer than anybody expected, but was necessary to ensure that the groundbreaking project would properly protect the marine habitat while effectively harnessing the renewable wind available at the site.

In contrast with West Virginia's coal and the Gulf of Mexico's oil, wind power is a renewable resource that can reduce the carbon dioxide emissions that cause global warming. Unlike burning coal in power plants or using oil to power our vehicles, wind farms do not emit particulate soot, nitrogen oxides, and other toxic pollution that triggers asthma emergencies, cancer, heart attacks and premature deaths. And of course, wind power is free of the environmental destruction that follows when things go wrong in the fossil fuel exploration business.

New York is one of the leading states for wind power in the nation --- and its growth is just taking off. As of the end of 2009, existing projects contributed 1,274 megawatts of capacity to our power grid, ranking New York eighth in the nation in terms of existing wind energy capacity. Perhaps most significantly, roughly 850 of these megawatts have come online in the last two years.

Upstate New York's wind projects are much smaller than Cape Wind or a typical coal-burning power plant – they range from 20 to 126 megawatts, in contrast to the 420 megawatts planned for Cape Wind and the 667 megawatts generated by the typical coal plant. In order for wind power to replace a significant amount of fossil fuel energy, New York's nascent wind industry has to move toward utility-scale projects on the scale of Cape Wind and other projects that have been proposed elsewhere along the eastern seaboard.

Wind at Sea

A utility-scale offshore wind facility has several advantages over smaller, land-based wind farms upstate. First, ocean-based wind power is stronger, more consistently available, and could be situated closer to Long Island and New York City electricity customers. Second, unlike ocean-based wind power, the availability of land-based wind power tends to decrease during the hottest part of a summer day, which coincides with the times of peak electricity demand in the downstate region. Third, because ocean-based wind power would be closer to consumers, transmission costs should be lower than remote, land-based wind power sources. Of course, community concerns about visibility of the turbines from shore, the need for new or reconfigured transmission lines, and any potential impacts on birds or marine life have to be addressed, and any significant environmental impacts must be identified and mitigated.

The Long Island Power Authority, the New York Power Authority, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the Port Authority, the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority and the city’s Economic Development Corp. have teamed up with Con Edison to explore the possibility of a utility-scale wind development that would be located roughly 13 nautical miles off the Rockaway Peninsula in the Atlantic Ocean.

The concept for the offshore wind project emerged from Gov. David A. Paterson’s Renewable Energy Task Force and is consistent with the governor’s “45 by 15” program, which set a statewide goal that the state must meet 45 percent of its electricity needs through improved energy efficiency and renewable sources by the year 2015.

The group is considering a wind project that would generate up to 350 megawatts of power initially, building up to 700 megawatts. At this scale, the project would be the largest offshore wind project in the country --- and would remove carbon dioxide gases equivalent to removing 68,000 cars from our region's roads annually. Operating at 30 percent of its capacity, a 700 megawatt project would generate enough energy for a half million homes.

Like Cape Wind, the path to developing this project will be filled with many procedural steps. In June 2009, the project's sponsors issued a “Request for Interest” that sought to gauge industry interest in the project. The responses to that request now are being used to create a “Request for Proposals” (RFP) that should be released soon. At that stage, New Yorkers will get a clearer sense of the exact location, cost and other details of the various proposals that will be considered. A joint Long Island Power Authority/Con Edison feasibility study has already concluded that, with upgrades to their existing transmission systems, the project could connect to up to 700 megawatts of offshore wind power to the power grid . Toward that end, an application to “interconnect” the offshore project has been filed with the New York Independent System Operator, the operators of the state’s power grid, to supply up to 700 megawatts by 2015.

By itself, wind power -- whether utility-scale offshore projects or generated in smaller projects upstate -- will not be sufficient to wean ourselves from our addiction to dirty fossil fuels. Combined with cleaner, more efficient power plants; increased efficiency in our buildings, appliances, and vehicles; and as part of an array of renewable fuels that includes increased solar power and advanced biofuels, wind power can be a significant part of our long-term climate and energy solution. As we continue to watch the Deepwater Horizon disaster unfold and learn more about the dangers and risks of coal mining and coal-fired power plants, the potential benefits of each of these strategies need to be explored fully.

Rich Kassel is a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, where he focuses on urban air pollution and transportation issues. He also chairs the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, a regional transportation advocacy organization; is on the board of the New York League of Conservation Votes and blogs on a variety of environmental issues on the NRDC Switchboard.

Can the City -- and the Oyster -- Save Jamaica Bay?

Photo by Unforth

The marshes of Jamaica Bay have been shrinking for decades, essentially vanishing into New York's toxic waters.

The largest urban wildlife preserve in the United States sits adjacent to Kennedy Airport, near the high-rise apartments of Starrett City and the Rockaway housing projects. Home to the peregrine falcon, the loggerhead sea turtle, the short-eared owl, the area -- Jamaica Bay -- at the intersection of Queens, Brooklyn and Long Island, serves as a stopover for 20 percent of American bird species on their annual migration along the East Coast.

For years, though, this estuary, a shallow marsh where fresh and saltwater meet, has been vanishing into the toxic waters of the New York City harbor, losing an estimated 33 acres annually to deterioration, nitrogen buildup and rising sea levels. Spanning some 16,000 acres about a century ago, the salt march islands have shrunk to a mere 800 acres. Thought not nearly as dramatic as the environmental catastrophe now confronting the Louisiana coast, the threat to Jamaica Bay could completely destroy the marsh by 2024, decimating the home for an abundance of rare and endangered plants and animals.

"Marshland completely changes the nature of the bay," says Larry Levine, staff attorney for the Natural Resource Defense Council. "If it were to ever disappear and become open water, it would be a tremendous loss of natural habitat."

Now, the federal state and city governments, prodded by citizen's groups, have stepped up their efforts to preserve the area. This year, government and private groups collaborated to update the Jamaica Bay Watershed Protection Plan to try to avert disaster in the urban refuge. Whether government will keep its commitment and whether its actions can reverse the decades of deterioration remains to be seen.

[For more on efforts to revitalize New York's waterfront, go here.]

Destruction of an Ecosystem

Spartina cod grass anchors the land of the marsh in place. To survive, the grass must receive fresh water rich with oxygen and nutrient-loaded sediment. Small streams in Queens and Brooklyn once provided this, but many of these vital veins have been paved over the decades.

Four sewage plants ringing Jamaica Bay contribute further to the deterioration of the marsh by spewing 250 million gallons of nitrogen and large amounts of chlorine into the water every day. Ironically the nitrogen has worsened since 1992 when the government, in an effort to prevent pollution, banned the dumping of sewage into the ocean and instead diverted the treated wastewater into the bay. The excess nitrogen in the water is naturally converted into hydrogen sulfide, which kills the roots of the marsh grass.

In this nitrogen-rich environment, weed-like algae blooms thrive, suffocating the estuary by draining it of dissolved oxygen. Algae blooms kill the thousands of fish found floating belly-up in the very waters that are meant to nourish them.

In addition, during heavy rains, untreated oils and toxins wash from nearby streets and parking lots when storm drains overflow and end up in the bay. The bay also shares many of the contaminants that pollute the rest of New York harbor, such as dioxins, PCB particles, and mercury.

"The New York harbor is a wasteland," said Jeff Levinton, professor of marine ecology at SUNY Stonybrook.

Photo by Gail Robinson

Humans have taken their toll on Jamaica Bay.

Next-generation issues also are emerging, explained Levine. Studies show that Jamaica Bay flounder are affected by pharmaceuticals flushed through the sewage system and not removed by treatment plants. The population of male flounder has drastically diminished because of the feminizing effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals -- a pattern Levine says is being observed around the world.

Sounding the Alarm

Dan Mundy, founder of citizen group EcoWatchers, noticed that Jamaica Bay was ailing in the mid 1990s. By 2000, he said, as many as 50 acres of saltwater marsh were being lost every year. And in 2002, the state authorized a study of why the marshland might be vanishing.

It was not until 2005, though, that Mayor Michael Bloomberg signed a measure calling for the city Department of Environmental Protection to devise a plan to save the bay and creating a seven-person advisory task force. The committee included community activists and representatives of nonprofit organizations and government agencies. The resulting report presented a number of options, including installing storm sewers for flood prevention, dredging and re-contouring creeks, restoring eroded land, re-oxygenating the water and hiring pump-out boats to clean waste. Overall, the committee wanted visitors to Jamaica Bay and the government to be more vigilant of the estuary's condition.

Gradually, steps to restore and preserve the marsh began. Between 2006 and 2007, the U.S Army Corps of Engineers allocated $13 million to restore Elders Point East, an island marsh which once spanned 132 vegetated acres, but which had broken apart to a mere 21 acres.

While activists applauded many of these efforts, a number of them faulted the city for failing to do more to reduce nitrogen levels in the bay. For years city officials maintained that little evidence linked the disappearance of the marshes and nitrogen levels in the bay and balked at spending millions and millions of dollars to address the nitrogen levels.

By 2010, New York City faced a possible lawsuit under the federal Clean Water Act. The threat spurred intense negotiations between citizen groups, the Department of Environmental Protection, then Deputy Mayor Edward Skyler and other City Hall officials. The city, according to Mundy, expressed concern about the cost of the technological upgrades needed to address the nitrogen problem, but over time became convinced that the installations were necessary for the bay's survival.

"It shouldn't be a matter of economics. Not when it comes to the environment. Not when it comes to Jamaica Bay," Mundy said.

Cutting the Nitrogen

In February 2010, Bloomberg announced the city would commit $115 million for a combination of efforts to safeguard the only wildlife refuge accessible via subway. As part of that, he said New York would spend $100 million to install new nitrogen control technology at sewage treatment plants on the bay.

Don Riepe, who headed negotiations on behalf of the American Littoral Society, said the city pledged another $15 million to support marsh restoration. The Army Corps of Engineers will match the restoration funds two-to-one.

The first of the plant upgrades will begin operating in 2014. Technology to control nitrogen will be installed at the 26th Ward and Coney Island wastewater treatment plants in Brooklyn, and at the Rockaway plant in Queens. These efforts are predicted to reduce nitrogen discharges by 50 percent over the next decade and to allow the bay to filter its waters over time.

Reclamation of Elders Point West Island has already begun. Clean fill, or "slurry" -- muck being dredged from waters around the city -- is currently being shipped from the harbor and Long Island and will become 35 new acres of marsh. The U.S Army Corps of Engineers is hand-seeding Spartina grass into the fill. When they finish this at the end of the summer, they will move on to reclaim Yellow Bar island.

Photo by Gail Robinson

Restoring grassland is essential to the survival of marshes so many animals call home.

Wave attenuators, marina-like docks that act as buffers against beach-deteriorating waves, are to be installed between 2014 and 2019.

Despite all this technology, though, Jamaica Bay's brightest new hope may be a bivalve that once lived in the 350 square miles of the estuary: the oyster.

A Natural Solution

Oysters last thrived in the Hudson-Raritan Estuary in the early 20th century. Describing the bivalve as a "keystone" species that affects other components of its ecosystem, NY/NJ Baykeeper has championed experimental oyster farming. Every animal can filter nitrogen and pollutants from 50 gallons of water daily. They eat oxygen-guzzling phytoplankton that suffocates the bay. In, addition the beds where the oysters live serve as homes for small marine organisms and the fish that feed on them.

"Right now you can hardly find a live oyster in Jamaica Bay," says Levinton.

Their decline both signifies and intensifies the bay's ailments. Chester Zarnoch, associate professor of natural sciences at Baruch College, and his colleague Tim Hoellein have received funds from the National Science Foundation to study the growth and survival of oysters in the estuary and to determine their potential in restoring it.

Zarnoch says that there has been tremendous growth and evidence of spawning where the bivalves have been re-introduced.