Damage Control

Last year, the Big Apple Sidewalk and Pothole Protection Committee sent the city map after map with 700,000 squiggles, each indicating an accident waiting to happen on a city street or sidewalk. Simply by receiving the maps, the city becomes responsible for fixing the defect, or is held liable if someone is injured by, say, tripping on a crack in the sidewalk

And that is why the pothole committee exists. Created by trial lawyers in 1982, it provides evidence and offers expert witnesses to testify. As a result of the committee's work, the city has paid out more and more money in personal injury suits. And so Mayor Michael Bloomberg's package of proposals to slash the amount that the city spends settling lawsuits takes particular aim at the pothole committee and its maps. "The maps offer no insight into whether a defect is a serious hazard or if it should be repaired promptly," the mayor's office said. Bloomberg has asked the New York City Council to approve a bill that would require more detailed description of fractured sidewalks and pitted pavements, instead of the committee's squiggles.

Last year, New York City paid out almost $600 million in claims and judgments as a result of lawsuits, up from $21 million in 1978. Most of these claims involved personal injury and a third of those concerned medical malpractice at city-owned hospitals. With the city struggling to close a $5 billion budget gap, the mayor argues that the amount spent on personal injury claims is greater than the entire budgets of many city agencies and says the money "could be far better spent on social issues."

Like Bloomberg, the last three mayors tried to overhaul the system under which people sue the city and collect damages for legal wrongs. But these efforts, generally lumped together under the name "tort reform," failed in Albany, at least partly due to vigorous lobbying by trial lawyers.

In the fight over changes to the legal system, the city and business groups point to what they see as excessive awards and frivolous litigation that hamper government and business.

"We can no longer afford to be victimized by unfair and exaggerated claims brought by plaintiffs and their lawyers," former City Corporation Counsel Paul Crotty wrote ten years later. He accused trial lawyers of holding "taxpayers captive to laws no longer suited to the times," and said, "It is time New York broke free."

On the other hand, trial lawyers and some consumer advocates say that the system of civil suits gives the powerless their only chance against big corporations and big government. Ralph Nader, who has dubbed tort reform "tort deform," calls being able to sue "a unique pillar of our democracy. This is the pride of the world. Only in America can a worker dying of asbestos file a lawsuit and bring the asbestos manufacturer to court for actions two decades ago."

Limiting the right to bring suit, these advocates say, would erode the public's check on government and provide less of an incentive for the city to screen, train and discipline its employees, particularly those who make life and death decisions, such as hospital workers and police.

Efforts to change the existing laws is symptomatic of a "punish-the-victim" approach, says Hugh W. Campbell, president of the New York State Trial Lawyers Association, which runs the pothole committee.

HORROR STORIES

The mayor and others who argue that the system needs change seek to bolster their arguments with anecdotes of outrageous cases. For example:

In 1983, Andre Robertson, then a player for the Yankees, was speeding down the West Side Highway and entered a turn at 60 miles per hour. Robertson lost control of the car, and his woman passenger was thrown from the vehicle. Now a paraplegic, she sued Robertson and the city. The jury found the city was largely responsible for her injuries because it had not posted a warning sign in advance of the curve, a sign that might have alerted the speeding Yankee to slow down. She was awarded $10 million, mostly from the city, not from the shortstop.

Another case often cited is that of Daryl Barnes. A police officer saw him running down a Bronx street with an Uzi machine gun and told him to drop it. Instead, Barnes shot at the officer, who then chased him. Barnes, still armed, turned toward the officer. The police officer, reportedly thinking that Barnes was about to shoot, fired, crippling Barnes for life. Even though he pleaded guilty to assault, Barnes sued the city, charging the officer used excessive force. A jury awarded him $76 million, which the judge reduced to $8.9 million. The city has appealed.

But there is another side. Advocates such as the national public interest group Public Citizen argue that the state government gave New Yorkers the right to sue the city so individuals could serve as a check on municipal recklessness. Many New Yorkers, for example, supported Iris Baez's successful efforts to win damages from the city after a police officer choked her son, Anthony, to death in 1994. She received $3 million.

HOW WE GOT HERE

Judgments against New York City have been increasing for decades. In 1898 state law exempted the city from civil lawsuits for any alleged wrongful act, injury or damage. In 1929, the state legislature changed that, making the city "answerable equally with individuals and private corporations for wrongs of officers and employees."

But for years, the amount of money the city paid out in claims and judgments remained relatively low. That started to change in the 1970s. Former Corporation Counsel Crotty has attributed the sharp rise partly to an action taken by the state legislature in 1975. It abolished a rule that prevented plaintiffs from recovering damages from the city if they were even the slightest bit negligent or had accepted the risk of injury.

This decision made possible cases such as one, cited by the city Law Department, brought by two brothers who were seriously injured when they dove off Steeplechase Pier in Coney Island. Even though the two men had had a couple of beers and had to climb over a three-foot railing before taking the plunge, a jury ruled for the brothers, saying the city should have posted "No Diving" signs.

In response to the rapid rise in settlements against the city, the state legislature approved a number of reforms in the 1980s. But the city's costs from liability suits continued to rise, prompting Mayors Edward Koch, David Dinkins and Rudolph Giuliani to call for changes to limit suits. While some piecemeal legislation was enacted, the legislature did not approve any major changes.

In 1994 then-Mayor Giuliani and his Corporation Counsel Crotty took a more sweeping approach. To dramatize what they saw as the need for change, they cited the case of a subway mugger who preyed on the elderly. A Manhattan jury awarded him $4.3 million for injuries suffered when he was shot as he attempted to flee the scene of his crime.

Giuliani and Crotty proposed placing a cap on how much money could be paid to compensate plaintiffs for non-economic damages, such as pain, suffering and the loss of a spouse's love. They also called for limiting the city's liability based on how much it contributed to an accident or other event.

In support of these provisions, Giuliani and Crotty relied heavily on anecdotes, cited legislation in other states and claimed that enacting similar measures in New York would save millions of dollars. They did not provide any hard evidence to back up such claims. The sole study that New York advocates of tort reform usually cite is a 1997 public opinion poll sponsored by New Yorkers for Civil Justice Reform, an advocacy group. In any event, Giuliani's proposal went nowhere.

In his effort to save the city money on legal actions, Mayor Bloomberg has proposed two bills, which would require approval only by the City Council, not the state legislature. One would replace the pothole committee. The other would make owners of buildings, not the city, liable for sidewalk cracks and gaps. Now, landlords are supposed to fix any defects but are not legally liable if they do not.

ROUTES TO REFORM

A number of ideas to change the tort system have been proposed by various people at various times. Other states have approved some of them. Most require a vote by the state legislature.

The changes could be limited only to suits against the city or could extend to all civil actions, whoever the defendant. It is generally thought that limiting the proposals to lawsuits that involve the city government would stand a better chance of approval -- although past experience has shown that the legislature has been reluctant to enact even those changes.

Overall, the issue comes down to whether the current system cultivates abuse or whether it provides needed redress to victims of misdeeds by individuals, governments and businesses.

One difficulty, reformers say, are juries that award plaintiffs huge sums of city money. To solve this, some recommend removing juries from the process entirely by putting all tort actions in the Court of Claims where they would be heard by a judge rather than a jury. This would require a state constitutional amendment.

Critics argue that such a measure flies in the face of our entire system of justice. Serving on a jury in a civil suit is a citizen's right and one way that ordinary people participate in public policy.

But judges already hear cases involving claims against the federal or state governments, says Walter Olson in City Journal. "For claimants, an important benefit would be that Court of Claims cases are resolved much faster than general court cases . . . . The city could still be sued on all the same legal grounds as now, and there would not be any set ceiling on damages."

Another approach would keep juries but limit their discretion in awarding damages. For example, New Jersey and Pennsylvania require that plaintiffs spend a minimum of $5,000 on medical expenses before they can collect damages for pain and suffering. Currently, New York has no such rule.

Others advocate setting a limit on how much a jury can award a plaintiff for pain and suffering, regardless of the severity of the injury or recklessness of the action. Crotty has noted that well over half of tort judgments and claims are paid out for "'pain and suffering,' a highly subjective and amorphous concept."

In one case, a jury reportedly awarded a victim more than $1 million for pain and suffering -- even though the person died only minutes after the accident. The trial judge reduced this to $75,000.

Opponents of caps say they are arbitrary. "Who is the mayor to say that the pain and suffering of one citizen is only worth $250,000," Hugh Campbell, of the state Trial Lawyers Association, has said.

And the critics argue that caps would unfairly deprive victims who suffer the worst injuries of their right to recovery. Conversely, defendants guilty of the most egregious actions would not be punished severely enough. Further, trial lawyers claim that there already is a check on excessive judgments -- appellate courts that can reduce or throw out a verdict.

City Corporation Counsel Michael Cardozo has also discussed reducing any damage award to a plaintiff by the amount the plaintiff recovers from insurance claims. Cardozo claims this would save the city $130 million a year.

THE LURE OF THE TREASURY

Damage suits against the city have skyrocketed , the New York Times wrote in an editorial not because the city has "become significantly more careless" but because of "a legal climate in which the city is seen as an easy mark and a deep pocket."

And city government is ubiquitous. It touches the lives of New Yorkers in a way unmatched by few if any corporations. The government creates and operates sidewalks with cracks, streets with potholes, hospitals where fatal mistakes can be made, schools where children can be injured, parks where toddlers can fall.

Finally, a corporation or individual hit with millions of dollars in damages can file for bankruptcy; the city cannot. In fact, under the law, if the city and another defendant are found to be jointly responsible for an injury, and the other defendant is broke, the city has to pick up the entire tab for damages.

Over the years, the city has made a number of proposals to make it less enticing to plaintiffs. One, embraced by Mayor Bloomberg and already in effect in Ohio and Arizona, would require that plaintiffs hold less that half of the responsibility for their own injuries. Currently, the city may be held liable for its percentage of liability, even if the plaintiff was 99.9 percent at fault.

Similarly, in a case where there are two or more defendants, the city would like to have all the defendants pay damages according to their responsibility. In other words, if a jury determines that a driver is 80 percent responsible for an accident in which a motorist struck a pedestrian and the city is 20 percent responsible, the city would have to pay no more than 20 percent of the damages. Now, if the driver cannot pay, the city must make up the difference.

Opponents argue this would place an unfair burden on the victim, who would be the big loser if the wrongdoer is not able to pay. The current system, they say, puts the onus for recovering damages where it belongs -- on defendants and on all of their actions.

Another idea would be to restrict someone's ability to sue for injuries he or she received while committing or fleeing from a crime. The city would, however, remain liable for damages if a police officer or other employee deprived someone of his or her constitutional rights.

BLAMING THE LAWYERS

Lawyers who win liability lawsuits receive as much as 40 percent of the total award. Supporters of reform claim that more money should go to the plaintiffs and less to attorneys. These critics believe if attorneys get less money from legal actions, they would be less likely to sue.

Attacking lawyers has a wide appeal. But Nader for one says it is not that simple. If lawyers got less money, he says, they would be more reluctant to take on risky cases. And he notes, the other side of the high percentage is that when trial lawyers lose, they get no money at all.

SCALES OF JUSTICE

Obviously, the city wants to reduce the amount it pays out in legal damages. But critics of changes, including Campbell of the trial lawyers, say proposals such as caps or limits to liability are the wrong approach. The way to reduce suits, he says, is to prevent the wrong from occurring in the first place.

Will the various reform proposals really reduce the city's costs in claims and judgments? And if money is saved, will it go to safety, education, or welfare? Conversely, is there any evidence that damage claims serve as a check on city government? Although city tort costs have increased over the years, are we any safer?

An ideal plan would somehow hold the city responsible for its mistakes and encourage safer streets, hospitals and schools, while at the same time saving the city money and limiting huge verdicts in frivolous cases. Striking that balance presents a daunting task under the best of circumstances, let alone in the face of a budget crisis and energetic lobbying on all sides of the issue.

Jonathan Rosenbloom is associate director of the Center for New York City Law at New York Law School. Joshua Beardsley assisted in research.

Technology and 9/11

The attacks on the World Trade Center succeeded in devastating New York's telecommunications infrastructure. However, a recent meeting of the City Council's subcommittee on technology brought to light the many ways in which technology was used to overcome the challenges of 9/11.

From Verizon and IBM to the Chief Medical Examiner's Office and the Housing Authority, technology played an important role in the rescue and emergency management efforts.

Maps

With the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications displaced from its offices and without access to computers, mapping experts had to recreate a map of the city. Luckily, Professor Sean Ahearn of Hunter College had a copy of the citys graphical information system (GIS) database. The Emergency Mapping and Data Center created in response to the attacks operated 24/7 for two months and handled 2,600 requests for information. In order to facilitate the use of these maps, the center produced a unique identification number for all city buildings. The mapping experience gained from the attack on the World Trade Center helped in the creation of a mobile mapping center to respond to the crash of American Airlines Flight 587 in Queens in November.

Databases

The attacks made it painfully clear that city agencies do not possess a common database system. Thus, the families of victims had to fill out the same form many times over -- until IBM created a software program that allowed the data to be entered electronically and transmitted to different agencies. Databases also allowed the Chief Medical Examiner's Office to create automatic death certificates, scan and archive important documents, track collected DNA and match DNA with the victims. In addition, there is no online directory of emergency contact information for city employees. This made it difficult for city employees to work from home following the attacks.

Global Positioning Systems

Debris was tracked as it was removed from Ground Zero with the help of global positioning system (GPS) monitoring equipment. The system uses portable units to record information and transmit it wirelessly and securely to the Internet. The technology allowed the city to document the location and amount of debris efficiently and flexibly. It also allowed building inspectors quickly to inspect the damage to buildings surrounding the site of the World Trade Center.

Telecommunications

While there has been a lot of talk about using technology to decrease redundancy and improve efficiency, this does not apply to telecommunications networks. This is because in order to avoid the serious damage which occurred as a result of 9/11, telecom companies recommend that redundancy be built into future city infrastructure. This includes greater network resiliency, more diversity of routes, and extra capacity. Competition between telecommunications providers is important in providing redundancy. In order to achieve this, the city will need to sign contracts with companies in addition to Verizon. However, building redundancy into telecom networks is very costly, wiping out the savings that new technology promises.

Lessons

- The Internet survived when wired and wireless phones did not.

- Maps of the city are a vital resource in times of disaster.

- It is important to build redundancy into telecommunications networks.

- It is necessary to use decentralized databases or Internet-based data storage systems.

- City employees should be offered incentives and discounts on home computers.

- The city should give employees access to e-mail.

- Local, state and federal governments must share information across boundaries in order to avert public safety threats.

Of course, people -- government employees, the private sector, non-profit organizations and citizens -- were New York's most important resource following 9/11. Our city's techno-heroes found innovative ways to employ technology, and learned important lessons for future city tech policy.

Laura Forlano is a doctoral student studying communication technology policy at Columbia University.

9/11/01-02: The Swap, The Lease, The Governor, The Olympics, The Rest Of The City

Land use planning in New York City, previously covered only on the slowest of news days, has catapulted to the front pages -- and the front of public consciousness -- in the aftermath of September 11th.

Suddenly many, many New Yorkers are debating the merits of small-scale, pedestrian-friendly development versus dramatic skyscraping monuments

We argue about the resurgence of a district catering to the tenants of expensive office buildings versus a mixed-use, mixed-income downtown.

We are contemplating new development and transportation links in the outer boroughs.

We're talking about green architecture, affordable housing and (sometimes) living-wage jobs as components of the city's rebuilding process.

Perhaps most impressively is where and how some of these debates have been taking place. Thousands of us have attended the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation's public hearings and 4,500 people participated in the "Listening To the City" forum convened in July by the 85-member Civic Alliance to Rebuild Downtown New York.

Most participants believed that Lower Manhattan, with its nearly 12 percent commercial vacancy rate, doesn't need 11 million more square feet of office space just now, and that any plan for rebuilding downtown should address the city's affordable housing crisis and include more public institutions and cultural amenities.

The public's involvement has had an impact: it is partly responsible for the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation's decision to scrap the six original plans for the World Trade Center site and start fresh. That's great news, and it's worth celebrating. But it's important to remember that it's still unclear how the story will end, where the money will go, and who among us will ultimately "recover" as a result of the post-9/11 rebuilding process. Here are some things to keep an eye on in the coming months:

THE SWAP

In early August, city officials proposed a land swap in which the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey would turn control of the World Trade Center site over to New York City in exchange for the land underneath Kennedy and LaGuardia airports, which the authority currently rents from the city. Civic advocates and government officials across the ideological spectrum seem to regard this plan warmly, though there have been objections from New Jersey Governor James McGreevey as well as from those who fear that the city would lose out financially on the deal or that the Port Authority would manage the airports to New Jersey's advantage.

Putting Lower Manhattan redevelopment in the city's hands would likely ease the pressure to build up the World Trade Center site with office space. Given the importance of WTC revenues to the Port Authority's finances, it isn't surprising that the authority has pushed for offices, but the city would likely have more leeway to develop the area as a mixed-use district. From the point of view of people who want to see diverse development downtown Ăś- and also from the perspective of those of us who want federal recovery money widely distributed to benefit all the communities whose residents suffered from the post-9/11 economic shock Ăś- having the city at the controls is probably a good thing. Because a city-guided process may be subject to the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) mandated by the city charter, redevelopment would also likely be more open and participatory under the city's supervision than it would be under the authority's.

THE LEASE

If the city does take the reins of downtown redevelopment, and if it goes for a smaller-scale office plan, the Bloomberg administration will have to decide how to re-negotiate developer Larry Silverstein's 99-year lease on the World Trade Center site. There have been murmurs from Swiss Re, who is Silverstein's insurer, that it would more willingly pay a large settlement if the proceeds went to the people of New York in some form, and this larger insurance payment could be the basis of a deal giving the city more flexibility with rebuilding .

But Silverstein remains an unknown quantity, and it is unclear how a deal with him would affect the city's ability to realize financial returns downtown commensurate with what it would have gotten from its airport leases.

THE GOVERNOR

Even if the Port Authority takes a smaller role, the city's choices about how to rebuild Lower Manhattan will still be constrained, as they so often are, by decisions made in Albany. Governor George Pataki made a majority of the 16 appointments to the Board of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation and thus has a great deal of say in how federal recovery funds (such as $2.7 billion in Community Development Block Grant money) will be spent. Recently, the election-minded Pataki has been saying all the right things about equitable rebuilding in the city, but his actions tell another story. So far, all three of the New York State-sponsored housing construction deals financed for Lower Manhattan by federal recovery money have been dedicated to luxury rentals (five percent of the units have been designated as "affordable" Ăś requiring family incomes of $70,000 to $90,000).

This in the face of the city's worst housing crisis in decades. Mayor Bloomberg, along with advocacy groups like Housing First!, are calling for incorporating affordable housing into planning for downtown. Is the governor signaling that he has no interest in including low- and middle-income working families (including the families of many firefighters, police officers and emergency service workers) in a rebuilt downtown community?

THE OLYMPICS

The World Trade Center redevelopment buzz was eclipsed this week by the news that New York City has become a finalist in the competition to play host to the 2012 Olympic Games. Whether or not the city is ultimately chosen, the Olympics, together with Ground Zero planning, is likely to dominate New York's land use agenda for the rest of Mayor Bloomberg's first term. Playing host to the Olympics would present a wonderful opportunity for the city to show its rich, vital culture to visitors from around the world. However, activists from low- and middle-income communities (particularly the waterfront neighborhoods that figure heavily in the Olympic plan) want to see more benefits and protections for their constituents built in from the beginning. The titanic land use changes proposed in the Olympic blueprint, while they promise to improve parklands and stimulate new development, will threaten the homes and jobs of low- and moderate-income residents unless displacement prevention measures like inclusionary zoning are in place from the start. There is also concern that other important planning initiatives, such as brownfields redevelopment, will get short shrift from the city in the midst of Olympic hubbub.

The constituencies recently energized around WTC redevelopment may soon mobilize around this new land use issue.

THE REST OF THE CITY

There is a strong case to be made that the entire city has suffered devastating consequences as a result of the September 11th attacks. This is most true with respect to job loss. According to the Fiscal Policy Institute, the five occupations in which the greatest number of 9/11-related layoffs have occurred are waiters and waitresses, janitors, retail salespersons, food preparation workers and cashiers. An estimated 60 percent of the 79,000 workers laid off earned less than $11 an hour. Since it is almost certain that the vast majority of these workers do not live in Lower Manhattan, there is a good argument for spreading redevelopment funds throughout the five boroughs.

The idea of using recovery funds to stimulate commercial revitalization and light manufacturing outside Lower Manhattan is gaining currency. The "multi-centered city" notion recently received a boost from Metropolis Magazine, which imagined cultural, retail and industrial hubs in Staten Island, Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx, linked to one another and to Manhattan by rail and ferry.

Though less directly related to physical rebuilding, a proposal by the Labor Community Advocacy Network for a short-term economic stimulus in the form of 75,000 new jobs also deserves consideration.

Thinking about what should happen downtown in the aftermath of the 9/11 tragedy has given New Yorkers a chance to ruminate on what kind of city we want. We have thought about how to remember the dead and how to address the needs of downtown residents whose neighborhood was turned upside-down last September. We have also reflected on how we want our city to look, how we want it to function for pedestrians, drivers and public transport users, and how we would like its land uses to address the housing and employment needs of its citizens. The results of some of these reflections, widely broadcast last summer, helped change the terms of the debate on downtown. But it isn't over yet. As the process continues, we must keep letting our elected officials know what kind of New York we want to result, in the long term, from the planning and investment decisions they are making today.

Sites For Beginners:

- How Zoning Works - An overview of zoning: its definition, purpose and implementation in NYS and NYC. This primer also explains who has authority to make which decisions, with accompanying laws and citations. Excellent.

- NYC Department of Planning - The official City site. Not frequently updated, but a good repository for official New York City Land Use documents. Find the complete text of the Zoning Resolution (a hard copy would run you $400+) and downloadable zoning maps. Find out which zone you live in!

- Regional Plan Association - The venerable and still influential pro-planning organization. Particularly good for information on big-item controversies, e.g. Governor's Island. Second Avenue subway, anti-sprawl legislation. Check out their MetroLink proposal and the Gowanus Tunnel Study.

- NY Metro APA - A small site for the local chapter of the national professional organization: American Planning Association.

- Municipal Arts Society - A great place for all things regarding New York planning, architecture and design. Most relevant: the just released Briefing Book of Community-Based Plans available to download, which offers for the first time ever a comprehensive look at the sometimes spotty, sometimes inspired plans for (and from) each neighborhood across the city, complete with maps and community contact information.

- NYU's Urban Planning Links Page - This page is chock full of great land use links which focus both on NYC and the USA.

Other Recommendations:

- Air Rights - An old Gotham Gazette Issue of the Week, still relevant and interesting, though a slightly arcane Land Use topic.

- Tenant Net - A great source for NYC real estate, if slightly biased toward the leassee.

- "The Cultivator by Martin Filler" - A fascinatingly critical article about Fredrick Law Olmsted and what's wrong with Witold Rybczynski's new biography of him. From The New Republic.

- New York Landmarks Preservation - Packed with information on preservation and restoration of landmarked buildings.

- New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission - The Official City site for landmarks preservation.

- Pace Law School Center for Land Use - Excellent introduction to land use issues by a leading academic think tank. Check out the "Land Use for Local Leaders" section.

- Van Alen Institute - An immense amount of information on current and future NYC land use issues. Start with the well organized, user-friendly contents page and then zero in on your prime concern.

Why Zoning Reform IS Important

Though not totally dead yet, City Planning Commissioner Joe Rose's attempt to make much-needed reforms to New York City's 1961 Zoning Resolution are likely to fail. Last month, I tried to explain the political reasons why this was so. Now, I would like to explain why this is a shame - why we need these reforms.

The 1961 overhaul was based on misguided principles.

As William J. Stern explains in a recent article in City Journal: "At a time when New York manufacturing employment (much of it low-paying) was already beginning its long decline, [planners] zoned whole sections of the city for manufacturing. Thinking that the city's population was growing too quickly, they forbade residential development in industrial and commercial parts of the city, so that great swathes of the five boroughs, including much of the precious waterfront, is off-limits to would-be builders of apartments or of offices for twenty-first-century businesses."

This is still one of the major reasons waterfront development stagnates. But Stern continues: "And they wanted the city to embody the vision of the then-celebrated Swiss architect Le Corbusier, who favored giant, boxy towers isolated in big, open plazas, so they allowed builders to make their edifices taller, and so boost rental footage, if they set them back from the sidewalk and surrounded them with open space."

Le Corbusier's influence was felt across America in planning in the 1950's and 1960. Most planners decided his "tower in the park" vision was the answer for development, and blindly guided their planning in that direction. It wasn't until most of these buildings were completed that people (starting with Jane Jacobs) realized how awful this type of development was. The buildings were of an inhuman scale, inaccessible in both an aesthetic and an actual physical sense.

The 1961 Overhaul made Zoning too complex.

As Joe Rose said in his speech upon announcing the reforms: "many of the problems we confront in zoning today derive from tentative and haphazard attempts to correct some of the structural mistakes that were made in 1961. Our present regulatory morass is the result of hundreds of amendments that nibble at the flaws of the original document."

Rose is not the only one who feels this way, Norman Marcus has compared the 900-page Resolution to detritus on the bottom of a whale. A cottage industry of New York City zoning lawyer exists with the sole specialty of interpreting the code for developers. That is not, nor was it ever meant to be, the way zoning should function.

Commissioner Rose sums up these two issues: "Our current predicament is that our zoning resolution has a discredited underlying vision, tempered by a series of quick fixes of varying effectiveness, for a city that was mostly built under a completely different set of regulations. No wonder we're confused!"

So, it's pretty much agreed that there's a lot wrong with our current zoning resolution, but pointing to what's wrong is the easy part. The current status of reform shows that it is far from agreed if changes should be made, what those changes should be, and if those changes will ever happen.

By next month we'll know more, if the reforms are dead or alive. If they're dead, the window is closed. If they're alive, then for how much longer?

Joshua S. Trauner, who has a Masters in Urban Planning from NYU's Wagner School, is vice president of Real Capital Analytics, a new company creating a database of real estate transactions.

Darkhorses Win International Competition for TKTS Booth

Two darkhorses from Sidney, Australia won the prize in an international competition to create a new TKTS booth for Times Square. Sidney architects John Choi, 28, and Tai Ropiha, 36, designed a bright red grand staircase which will rise from the base of the statue of Father Duffy, for whom the TKTS traffic island is named, to a height of 16 feet. The TKTS logo will be emblazoned in bold black letters about 5 ft. high on the structure's north and south sides. Sales booths will be tucked in beneath the high end of the stairs, and after buying their tickets theatergoers will be able to sit on the steps looking out at the spectacle which is Times Square.

Choi and Ropiha, who visited NYC only once before returning last month to claim $5,000 in prize money, said they based their impressions of Times Square on films, magazines and television coverage of New Year's Eve celebrations. "We were reacting to the visual buzz," said Mr. Roipha, "and tried to create a strong singular image in contrast."

What was the jury looking for? "Something that had cleverness, visual economy and force," explained Jack Goldstein, executive director of the Theater Development Fund which operates TKTS and sponsored the competition. TDF was also looking for more booths as well as better working conditions for the sales staff within (They're even thinking about adding a public toilet). Construction, to begin later this year, is expected to cost around $2 million all to be raised by the Fund.

The competition, the largest ever in NYC history, drew 683 entries from 31 countries: ranging from a booth conceived as twin green crystals to a 3D rendering of Piet Mondrian's "Broadway Boogie Woogie." 40 top designs are currently on exhibition at the Van Alen Institute (30 West 22nd Street) while 200 more can be seen at the Urban Center (457 Madison between 50th and 51st). "There wasn't much room for an entirely radical solution," said Raymond Gastil, executive director of the the Van Alen Institute which organized the competition. "But the entries say a lot about the raw energy and talent that's out there."

Even the Coalition for Father Duffy which inundated the Mayor's office with over 7,000 postcards - "This is Duffy Square, it isn't TKTS Square," said the Coaltion head Maj. Gen. Joseph S. Healey. "You can't dump him from center stage and put him in the cheap balcony seats. It isn't fair." -was mollified by Choi and Ropiha's design.

But what about the existing TKTS booth - that wonderful, ramshackle, pipe-and-canvas construction which has come to represent Broadway theater to an entire generation since its inception 26 years ago? David W. Dunlap wrote in the New York Times (7/8/99): "The competition seems to doom one more facet of Broadway's architectural past, which has been chipped away piece by piece in recent years until very little remains of what was once a splendidly pungent esthetic amalgam, made of dozens of incongrous icons layered one on top of the other."

Dunlap went on to point out that the old TKTS booth was the product of that moment in the early 70's when Broadway was desperate for resuscitation and the city nearly broke. Under Mayor Lindsay, the Office of Midtown Planning and Development lent a city-owned trailer to TDF to be used as a booth for selling half-price tickets on the day of a performance.

Bound to a budget of only $ 5,000, architects John Schiff and Robert Mayers came up with the idea of renting pipes by the month from the R. C. Mugler scaffolding company in the Bronx. With these pipes, they extended the structure outwards - then streched translucent plastic through and around the pipes and painted "TKTS" in large Helvetica letters across. To keep the whole thing from blowing away, they lashed it to four rough concrete anchors at each corner.

The TKTS booth was an overnight and abiding success. More than 36.5 million tickets have been sold there since it went up. It won a design award in 1973 from the New York Society of Architects, a Bard Award in 1975 from the City Club for merit in civic architecture and has been called "a classic of early 70's design" and "the beginning of scaffold-like, high-tech, tensilt structures. Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani has referred to it as one of the "symbols of the renaissance" of New York City. Ron Silver who chaired the NYC 2000 millenium committee called it "Times Square's centerpiece."

But while preservation advocates believe a case could have been made for granting the booth landmark status, it would not have been eligible till turning 30 in 2003. And it probably would not have stood up that long. Even Mr. Schiff admits the booth was always meant to be temporary.

Kati Sounds Off:

There's a lot of talk in this town about "the community" and the arts are by no means exempt. Take the theater. In a recent issue of American Theater magazine, Ben Cameron, executive director of the Theater Communications Group, sang the praises of "community-specific [eg Latino, Asian-American, gay/lesbian] theatres" which, he claims, "speak to a unique need many have for communal celebration, for empowerment, for safe places to come together in an all-too-often hostile world."

Well, maybe. But it's also true that you gotta have a gimmick to get funded and one of the easiest gimmicks to have is community service/specificity. Meanwhile the proliferation of community-specific companies has led to a balkanization of the larger theater community - at least at its not-for-profit edges - as well as to a sort of unquestioning acceptance of the myth of cultural identity: an acceptance which is ultimately impoverishing both intellectually and imaginatively.

This is not to say there aren't scores of wonderful counter-examples - Pan Asian Rep, the Irish Rep, the Negro Ensemble Theater, the Puerto Rican Travelling Theater Company - to name a few. Nor that at one point the flowering of community-specific theaters did not serve a very necessary, corrective function.But as an overall trend, it's gone too far.

Kati Kormendi is a freelance writer and actress; the former Artistic Director of the Magellan Project, a multiarts theater; and the creator of The Serpent's Eye an online eco-art gallery. She has written for Mademoiselle, Cosmopolitan, and Talking Leaves magazine.

Lawmakers Propose Restrictions on Prison Solitary Confinement

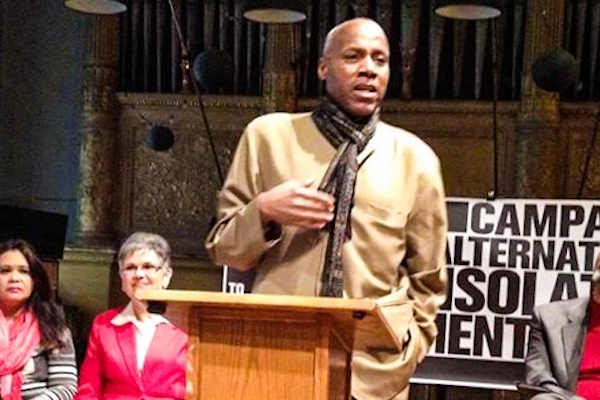

State Sen. Bill Perkins, a sponsor of the proposed HALT Solitary Confinement Act, discusses the bill at a community forum Friday in Manhattan. Photo by Bernadette Evangelist.

More than 5,000 inmates are held in solitary confinement in New York’s state prisons and city jails - a condition two legislators hope to change by reforming what they see as a torturous practice.

State Sen. Bill Perkins (D.-Harlem) and Assemblyman Jeffrion Aubry (D.-Queens) introduced a bill Friday that that would drastically scale back the use of solitary confinement, which isolates an inmate in a small cell for 22 or more hours per day.

Their proposal, the Humane Alternatives to Long-Term (HALT) Solitary Confinement Act, would cap solitary terms at 15 days. It also calls for the use of therapy and rehabilitation units as alternatives to isolating inmates in tiny cells, except in the most egregious cases.

Jessica Casanova, a family worker from East Harlem said she first became aware of special housing units (SHU), as solitary is called in the prison system, two years ago when she received a disconcerting letter from her nephew Juan Díaz.

In the letter, her nephew called SHU a "steel coffin," and wrote that, "I'm breathing, but I'm dead," Casanova said Friday.

Díaz, 32, was sentenced to 46 years to life after his conviction in 2004 on charges that accused him of robbing and beating to death a handicapped man. He was accused in November of using a homemade weapon to stab a prison guard in the head and abdomen. The guard recovered.

Confined at the maximum-security Upstate Correctional Facility, Díaz had been in solitary for two years when he wrote his aunt. Casanova rushed to visit him, only to find them divided by Plexiglass that prevented her from giving him a hug.

Casanova said Díaz has been in and out of the SHU during the past 12 years.

A recent count at Rikers Island, the city's largest jail, found that one in seven inmates in a population of more than 10,000 were being held in isolation.

Perkins traces the large number of inmates held in solitary confinement to the attitude of corrections officers towards inmates.

It's customary for guards to place inmates in solitary confinement for anything from the possession of tobacco to a messy bunk, according to a report by the New York Civil Liberties Union. When violence or gang activity are involved, the Department of Correction views solitary confinement as protection, either for the person being sentenced or the rest of the prison population.

"If two inmates get in a fight, they have to be separated, they have to be protected from each other," Martin Horn, the former New York City DOC Commissioner, told Gotham Gazette last year.

The city DOC said it was too soon to comment on the proposed bill and a spokesperson for the state Department of Corrections and Community Supervision said they do not comment on pending legislation.

HALT’s proposed 15-day limit on solitary confinement would be in keeping reform advocated by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on torture.

"The bill is a fundamental transformation of the way the prison deals with misconduct," said Jennifer Parish, an attorney with the Urban Justice Center and founding member of the Jails Action Coalition. "It's a transformation from a punitive response to one that's more focused on assisting people with underlying needs that cause them to act out."

Such organizations as Human Rights Watch and the NYCLU are working to expose the psychological toll that the lack of human contact and outside stimulation has on inmates, many of whom will be released back into their communities.

The HALT Act would prohibit the use of solitary confinement for protection and would mandate that inmates be placed in traditional solitary cells for only the most egregious infractions, such as violent assault or attempted escape.

The punishment would be eliminated altogether for inmates who fall into a number of "vulnerable populations," such as those under 21 and over 55 years old, as well as anyone suffering from a disability or mental illness and anyone who identifies as LGBT.

When asked whether the political climate in Albany is conducive to reforming policy on solitary confinement, Perkins responded with a question of his own.

"Have you been outside in the last few days?" he asked, referring to recent sub-freezing temperatures. "It's colder than that."

But Perkins predicts that "warm days are coming." They would come more quickly, he added, if the governor put the "moral and political weight of his office" behind the issue.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo did not immediately respond to a request for comment on the proposed legislation.

Mayor Announces Settlement Agreement on Stop-And-Frisk

Mayor Bill de Blasio came through on one of his top-priority campaign promises today with an announcement that he has reached a settlement agreement with civil rights lawyers who challenged the police department’s stop-and-frisk policy.

The police tactic hasn’t been used since August, when a federal judge ruled that the policy was unconstitutional. Former Mayor Michael Bloomberg appealed the ruling.

Reforming the policy that created the tactic will involve a more direct communication between city neighborhoods and the police department, de Blasio said. The mayor has in the past complained that the dialogue has been broken, instigating a rift between police officers and the residents.

A court-appointed monitor will oversee changes in police policy. The monitor will serve for three years and guarantee the NYPD is in complete compliance with the constitution. De Blasio also said he will install an independent NYPD Inspector General.

“This is a defining moment in our history. It’s a defining moment for millions of our families, especially those with young men of color,” de Blasio said in a statement. “This will be one city, where everyone’s rights are respected, and where police and community stand together to confront violence.”

Critics of the stop-and-frisk policy charged that it targeted Hispanic and African-American men. Bloomberg countered that white people were stopped. De Blasio has stood firm in his belief that the policy was overused and abused.

“We believe in respecting every New Yorkers’ rights, regardless of what neighborhood they live in or the color of their skin,” de Blasio said.

Judge Shira A. Scheindlin first ruled the policy unconstitutional and wanted to make immediate changes to the policy because of racial profiling. The ruling resulted in the judge being removed from the case by a three-judge panel of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals saying the judge “ran afoul.”

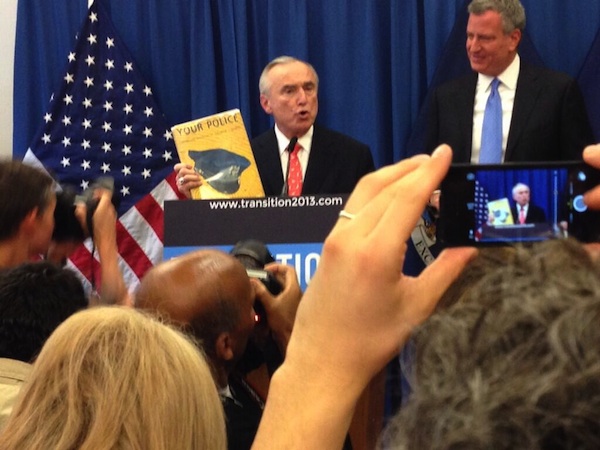

In reaching a settlement agreement in the case Floyd v. the City of New York, the mayor and Police Commissioner William Bratton pledged to repair a flawed policy.

“We are taking significant corrective action to fix what is broken,” de Blasio said.

Bratton, who helped initiate the stop-and-frisk policy under his first term as commissioner under former Mayor Rudolph Guiliani, attended the mayor’s news conference and said he is committed to keeping the law honest and fair.

“We will not break the law to enforce the law,” he said in a statement. “That’s my solemn promise to every New Yorker, regardless of where they were born, where they live, or what they look like. Those values aren’t at odds with keeping New Yorkers safe—they are essential to long-term public safety.”

Mayor De Blasio Promises Independent Police IG

NEW YORK — Bill de Blasio stood out from the field of mayoral candidates last year for supporting a set of City Council bills to strengthen the local ban on profiling by police officers and to create an inspector general to oversee the New York Police Department’s policies and procedures.

After swearing in his new police commissioner last week, de Blasio recommitted his support for filling the position with an “effective inspector general.”

“I want to emphasize the law is right — this individual will serve independently from the commissioner,” de Blasio said, as he stood with new NYPD Commissioner Bill Bratton. “At the same time, I expect a good and respectful relationship.”

The selection of New York City’s first inspector general for the police department technically falls upon the next commissioner of the Department of Investigation, which already oversees 14 inspector generals that operate across 30 city agencies. The independence of those inspectors, however, has never been scrutinized and debated the way the NYPD inspector general has.

Richard Aborn, executive director of the Citizens Crime Commission of New York City, explained that the law as written maintains an objective measure for accountability that is incorporated into the job.

“If you have elements of transparency built in to the office it maintains a sense of independence,” Aborn said, adding that the regular reporting requirements to both the Council and mayor already ensures a new level of auditing to the NYPD.

Even the appointment of a new head of the Department of Investigation requires a check from the City Council. Unlike most agency heads, the new crop of legislators need to sign off on the mayor’s pick for the administration’s lead investigator. Even so, de Blasio’s early support for the new position and the level of scrutiny all but ensures the mayor’s involvement in selecting an inspector general.

“We’re going to find someone who by definition commands public respect, and the respect of the men and women of this department,” de Blasio said.

Asked what role Bratton would play in the process of selecting the person charged with overseeing the police department, de Blasio said his new commissioner’s counsel wouldn’t compromise the inspector general’s mandate.

“I’m certainly going to discuss the situation with Commissioner Bratton before making any choices and seek his input. I want this to be a choice that we all feel good about,” the mayor said.

The position of inspector general for the police department came about after a long political battle in the heat of last year’s mayoral election. The City Council passed the bill creating the office but not without both conflict from within the body and with former Mayor Michael Bloomberg. The Council racked up enough votes for a veto-proof majority, overriding Bloomberg’s eventual strike against the law.

The bill itself was paired with the equally contentious expansion of the city’s profiling ban, the two being packaged as the Community Safety Act. Considered to be the Council’s response to the NYPD’s controversial stop-and-frisk policy, the inspector general bill in particular was also motivated by the police department’s ongoing surveillance of Muslim communities for counterterrorism intelligence.

Members of the American-Arab community argue that the police unfairly and unconstitutionally targets it on the basis of religion, and that there has been no link between the surveillance program and terrorist attempts in recent years. Former Police Commissioner Ray Kelly, who began his most recent tenure as top cop months after the Sept. 11 attacks, defended both the department’s intelligence gathering methods and the NYPD’s relationship with all communities.

Soon after his appointment, Bratton displayed his commitment for an inclusive police department by privately sitting down with leaders of the Muslim community.

Arab American Association Executive Director Linda Sarsour said she left the meeting on Dec. 12 feeling optimistic that Bratton was open to criticism from even the severest opponents to police practices under his predecessor.

“There were some of the most staunch police reform advocates at that meeting,” she recalled. “There were anti-Bratton people there, and the fact that those people were brought to the table was something Commissioner Kelly never did.”

Sarsour said she was cautiously optimistic about the ability of Bratton and de Blasio to follow through on reform priorities. She said her community celebrated the passage of the inspector general bill. But to make it work, Sarsour argued, the new administration needs to be able to use its subpoena power and work with a more transparent police department.

At his swearing-in on Thursday, Bratton promised as much and pointed to his past experience with the Los Angeles Police Department, where he served as police commissioner from 2002 to 2009. The LAPD has an inspector general whose mission is to provide “strong, independent and effective oversight.” Bratton joked that working with an inspector general again would be a “piece of cake.”

Bratton told reporters that the LAPD increased the inspector general’s powers, and that he himself had invited the inspector general to various crime scenes, staff meetings and disciplinary discussions.

“If you commit to make it work,” Bratton said, “it will work.”

Justice May Be Ahead For Central Park 5, But What About Key Police Reform?

Documentary filmmaker Ken Burns sparked some chatter among the political class yesterday when he told The Huffington Post that Mayor-elect Bill de Blasio would settle the 10-year-old Central Park Five civil lawsuit brought by the suspects — teenagers at the time — who were wrongfully convicted for brutally attacking a jogger in the park sued. But it's not really news that de Blasio would like to settle the case.

After all, back in January, de Blasio sent out a statement as public advocate calling it a “moral obligation” of the city to “right this injustice.” “It is in our collective interest — the wrongly accused, their families and the taxpayer — to settle this case and not let another year slip by without action,” he said in the statement.

De Blasio’s transition team directed us to the January statement when we asked about the mayor-elect's position on the Central Park Five case.

What may be news, however, is where de Blasio stands on the question of videotaping interrogations by law enforcement — a question that we'd like to answer. Why? Recall that the pivotal evidence in the case against at least one suspect in the Central Park Five case turned out to be a false confession.

As Gotham Gazette City Government Reporter Chester Soria explained in a recent story about false confessions, one of the main focuses of policymakers and advocacy groups working to redress the problem has been on getting police departments across the country to begin videotaping not only confessions but also the interrogations leading up to them.

As Soria writes, for reform advocates, “a written or videotaped confession only tells part of the story. Capturing an interrogation from beginning to end, on the other hand, creates an undeniable record that ensures the veracity of confessions.”

The question of videotaping interrogations was again highlighted in October when it was revealed that the New York Police Department had not recorded detectives grilling the suspect in the Baby Hope case. Back in 2010, Police Commissioner Ray Kelly had said he would start a pilot program to test videotaping interrogations; but, as The New York Times reported in its story on the Baby Hope case, only two precincts were videotaping interrogations of felony and sexual assaults as of October.

It’s unclear where the mayor-elect stands on the issue of videotaped interrogations and whether he will call for the next police commissioner to implement this reform which police reformers say is necessary.

The mayor-elect’s transition team didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment on Wednesday about de Blasio's position on videotapped confessions. Online searches didn’t turn up any statement from him as a candidate or public advocate, either. (Of course, if you find one, This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.)

NY State Mulls Bill Requiring Videotaped Interrogations

[This story is part of a series focusing on false confessions and filming interrogations published by Juvenile Justice Information Exchange. Read other stories in the series here.]

NEW YORK —The New York Police Department is willingly unfurling its own interrogation recording program, albeit slowly. And yet for some observers, it isn’t enough.

Across the country, lawmakers are making an effort not only to convince authorities to adopt the best practice but to push legislation that creates accountability and oversight of said programs.

New York state has been waging that fight for years now, leaving some local leaders looking for more immediate recourse on a municipal level.

One of the leaders in Albany pushing for legislative reform on interrogations, Brooklyn Assemblyman Joe Lentol, said he was happy to hear of NYPD’s move towards the 21st Century. He said internal best practices aren’t enough.

“That would be wrong and would still require legislation in order to make it work effectively,” said Lentol, a former prosecutor.

Almost every major independent criminal justice group and association in New York state supports the videotaping of interrogations. The District Attorneys Association of New York, led by Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance, holds that the recording of interrogations is best handled by individual jurisdictions as long as it doesn’t either strain resources or adversely affect the investigation or case.

The group has released its own proposal of best practices for recording, as have the New York State Bar Association and New York State Association of Chiefs of Police.

The practice has even caught the attention of N.Y. Gov. Andrew Cuomo. During his 2013 State of the State address, the governor advocated for legislation promoting the videotaping of confessions for suspects in violent crimes and sex offenses.

“This will give us more certainty that the convictions we obtain are actually fair and justified,” Cuomo said.

While a bill has yet to make it to a successful vote, Cuomo recently took steps to ensure that authorities can at least pursue the recording of interrogations while Albany sorts out the legislation.

In July 2013, Cuomo announced that the state would make $1 million available to agencies so that they could record criminal interrogations.

“Wrongful convictions not only harm the innocent, but they allow the actual perpetrators of crime to remain free,” the governor said. “The new equipment that will result from this funding will improve the strength of New York’s criminal justice system, making all New Yorkers safer as a result.”

And yet a bill requiring that all authorities adopt a program with oversight has yet to make it to the floor. It came the closest it has ever come to passing in early 2012, when Cuomo signed off on a legislative package that also expanded the state’s DNA database to include materials collected in misdemeanors cases.

The bills that passed originally included a mandate to videotape interrogations statewide, one of a number of recommendations outlined by the state’s Justice Task Force, headed by Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman. They were all eliminated before the bill made its way to the governor’s desk.

“In Albany, even if it seems like a no-brainer, it’s never a no-brainer,” Lentol said. “That’s what happens in negotiations.”

As a legislative issue, the recording of interrogations has been debated in the Albany Capitol since 2003 when former Assemblyman Adam Clayton Powell IV of Harlem first proposed a bill.

Lentol has since picked up the reins. Along with state Sen. Bill Perkins, the two have spent the last few legislative sessions working on a bill that would not only require minimum standards for recording interrogations but also create some exceptions to make the transition easier for police agencies.

{pullquote}The more transparent police and prosecutors are about interrogations, the more credibility our system has. — one lawmaker said.{/pullquote}

Lentol added that he didn’t think passage of future bills would be likely without another similar omnibus bill. And while there aren’t plans for such a package, the recording of interrogations seems to have stuck with Cuomo.

“The more transparent police and prosecutors are about interrogations, the more credibility our system has."

Perkins is more hopeful. Before joining the state Senate, Perkins pushed similar legislation on a local level as a City Councilman. Today, he still argues that the two key elements in question are transparency and accountability.

“There’s no place here that they’re more necessary than in the criminal justice system,” Perkins said. “The more transparent police and prosecutors are about interrogations, the more credibility our system has. Anything short of that contributes to that cynicism we saw in the Central Park Five case.”

Until Albany acts, Perkins thinks that there are some means for transparency, even if they’re not perfect. Referring to a recent law passed by the City Council, an inspector general for the New York Police Department might be able to help properly oversee its interrogations program — even if it’s not a perfect solution.

“An independent inspector general is maybe a better step in that regard, but it’s like the fox watching the coop,” Perkins said. “With all due respect to the good police officers, I would imagine that it’s even more so to their advantage to be able to show how correct they are and to be above any kind of cynicism about the outcome of their interrogations.”

But not everybody agrees that authorities need oversight. One of the inspector general bill’s most ardent detractors was Queens City Councilman Peter Vallone Jr., who, along with a number of local police unions, argued that the oversight bill was redundant.

“We might as well call our police commissioner ‘deputy monitor’ because they won’t be in charge anymore,” he said during a radio interview earlier this year.

His resistance to police oversight extended to that of the department’s interrogation procedure. Although Vallone supports NYPD’s decision to voluntarily videotape interrogations, he has pushed back on a need for external oversight from the city council or for statewide legislation.

If anything, Vallone said in a phone call, the myriad of regulations would create more "technical violations to get people off."