Mentally Ill Seek More Independence

photo by Gail Robinson

It's the simple things in life that bring Irene Kaplan a sense of joy -- things most people take for granted. Deciding when she goes to bed, how to decorate her apartment, when to take her medicine. She likes buying her own groceries, choosing what she eats and how she cooks it; lately she has been experimenting with Caribbean spices and wants to bake more bread.

"What people like about it is the smell of bread baking. It's absolutely drool worthy. I've been experimenting with multigrain bread and Italian style. I've been using different healthy oils. It's a whole new, wide open world once you get out of the home," she explained.

A bout of pneumonia and a telegram letting her know that she no longer had a job led to Kaplan's stint as a homeless person and her eventual arrival at an adult home, a for-profit facility where the state places mentally ill adults. Kaplan spent 16 years in such a home.

Earlier this month Federal District Court Judge Nicholas Garaufis ruled that keeping mentally ill people in these homes violated their rights by preventing them from functioning as part of society. The state is still deciding whether to appeal a decision that could have a dramatic impact on how New York cares for people with mental health problems.

Kaplan, though, has already left her home. Thanks to state funding for supported housing for 60 patients, she lives in her own small apartment in Brownsville. She gets therapy and assistance from local groups as she works to reconstruct her life.

Now as a result of Garaufis' ruling, more patients like Kaplan may have a similar chance at freedom. Whether that happens, though, depends on how the state responds.

Not So Welcome Home

Since the state phased out its mental institutions in the 1970s, it has grappled with how to deal with mentally ill adults. For-profit homes, such as the one where Kaplan lived, have become the standard treatment centers for mental patients in New York. Over 4,000 New Yorkers with mental issues are housed in adult homes throughout the city.

In 2002, the New York Times ran a series about adult homes and the problems that ran rampant in them at the time. Reporter Clifford Levy found abuse and neglect of patients and that homes subjected residents to unnecessary medical procedures to take advantage of Medicare. In a 2003 article the Times referred to adult homes as "little more than psychiatric flophouses."

Following the Times series in 2002, advocates and the Pataki administration moved to reform the adult homes. The administration proposed spending $8 million to send social workers and caregivers to adult homes to increase the quality of care and evaluate whether some patients would be better served in other settings. But after strong lobbying by owners of adult homes, the legislature took $6 million of that money and allocated it to a program to give cash bonuses to adult homes that fared well good inspections -- essentially, advocates say, bribing them to provide a decent standard of care.

A taskforce was put together by the Pataki administration to address the care of the mentally ill. It recommended that the state move thousands of mentally ill adult home residents to apartments or small homes in communities. This was all supposed to be accomplished by March of this year. In the end only 60 patients were moved including Kaplan.

Over the past several years, some of the abuses have been addressed with better monitoring from the state. Adult homes are licensed and regulated by the New York State Department of Health. The State Office of Mental Health licenses and regulates mental health providers that diagnose and treat patients in the adult homes. Homes are regularly inspected.

Patients and advocates say there are good homes and bad ones, but as a whole they say adult homes effectively cut off patients from the outside world while fostering a sense of dependency and helplessness. In effect, these new institutions, they say, have become prisons that warehouse patients without any eye to letting them return to society.

Going to Court

In 2003, lawyers representing thousands of adult home patients and advocacy groups filed a suit in U.S. District Court in Brooklyn alleging that the state had violated the Americans with Disabilities Act by segregating the mentally ill.

The lawsuit said that most patients would be better off in their own apartments where they could receive treatment. This, the suit said, would also save the state money. It asked the court to block the state from sending the mentally ill to adult homes.

In his decision, Garaufis ruled in the complainants' favor by agreeing that the state violated the rights of the mentally ill in New York City. But he stopped short of barring the state from sending patients to adult homes. Still, Garaufis indicated in the decision that the state should consider providing apartments or small homes to patients who are not a threat to themselves or others.

Garaufis ordered the state to submit a "remedial plan" by October. The plaintiffs, including disability advocates, will be allowed to critique the plan.

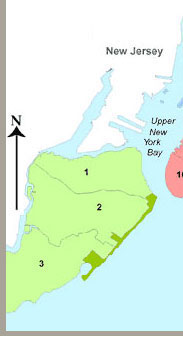

The ruling only applies to homes in New York City, but the state will likely have to overhaul the entire system by which it services the mentally ill. Advocates expect the decision to have national ramifications since many other states also rely on adult homes to care for the mentally ill?.

The Next Move

So far the Paterson administration has remained mum on its plans. Jill Daniels, spokeswoman for the state Office of Mental Health, said that the judge's 210-page decision is still under review. "It's a long decision. Multiple agencies are involved," she said. Paterson's office did not return calls for comment.

A number of advocates are calling on the Paterson administration not to appeal the decision. Glenn Liebman, chief executive officer of the Mental Health Association of New York State, said New York should instead do now what it could have done to avoid the suit in the first place. "The state should have moved years ago to change conditions in adult homes. The state should have done a better job. They did some good things but they did not take a comprehensive approach," he said.

Saying he is "pleased with the decision," Sen. Tom Duane, who serves on the Senate Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Committee, said he thinks "the Paterson administration is very sympathetic" to the ideas expressed in the ruling. Duane said he plans to work with the administration to develop more supported housing for the mentally ill.

Lisa Newcomb, director of the Empire State Association of Assisted Living, which represents some homes, criticized the decision for casting the entire adult home industry in a negative light. She said the decision seems to assume that many of the patients in the homes are capable of functioning at a higher level than they actually can. According to Newcomb, sizable number of patients probably need the care and supervision the homes can provide.

Newcomb added, though, that she recognizes that more options for independent living are needed. "Honestly, we need more of everything," she said.

Paying for the Alternative

The real struggle facing the state is likely to be financial. Advocates acknowledge that the state is confronting fiscal crisis and that finding affordable housing in New York City is no easy task. But they say that providing the mentally ill with an apartment and finding them therapy and other services in their areas will actually be less expensive than paying to support their stay in large adult homes. And advocates say that a support structure of case workers and healthcare workers will be readily available to the patients.

Garaufis agreed. In his decision, he wrote that it costs at least $7,946 a year less per patient for the state to provide "supported housing" to the mentally ill than to pay for a stay in an adult home, which costs around $47,946 a year. Garaufis also found that supporting a patient in an adult home costs Medicaid twice as much as it does to keep a patient in supported housing.

Advocates insist there are a number of funding options, federal and otherwise, that could initiate a supported housing program across the state. They say the program could be ramped up over the next few years.

The other financial consideration comes from the adult home industry, which is not exactly keen on giving up a steady source of income. Advocates say adult homes are represented by a "very powerful lobby," that has been able to get its way with the legislature in the past.

Rediscovering Independence

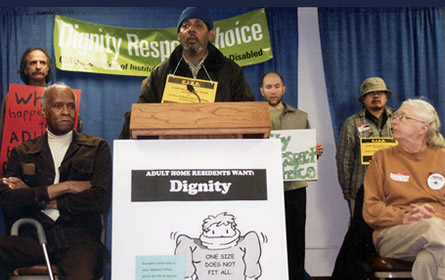

Adult home residents speak out at a press conference in 2005

In his decision Garaufis pointed to the stigma of living in an adult home and said it can curtail social and professional options. The rules and restrictions, such as limits on visitors and not being able to have a phone, run counter to the image of an independent functioning person. Garaufis also noted that, while homes tend to focus on training in life skills, such as cooking and shopping, residents rarely have the chance to apply their skills in society.

Advocates acknowledge that not all patients will be ready to live on their own, but they say they should have the choice. Kaplan, who as a member of the Coalition of Institutionalized Aged and Disabled has been very active in advocating the rights of the mentally ill, agrees.

She admits that some patients need more help than others, but believes more harm than good is being done by keeping them all in one place and segregating them from society.

At Surf Manor Homes in Coney Island Kaplan was told what and when to eat and when to bathe. She had limited contact with the outside world and recalls being scolded for changing her linens, being coerced and intimidated into following instructions, and having to pick her roommate off the floor at night. She particularly remembers suffering summers without air conditioning.

Kaplan said she knew she was simply "too functional" to be in an adult home. "I did a lot of things for myself: I clean my room, take care of my personal hygiene needs. I didn't need that kind of support," she said.

While Kaplan recognizes that not everyone is as functional or independent as she is, she said living in a home erodes a person's self reliance. She says it is hard for some, after years of regimentation, to fight for more freedom or even to want it. "They do your shopping, do your cooking, help you shower. It is not conducive to a sense of independence," she said

Ready for the Next Move

Derek White, though, wants to move on. Three or four years ago he was living on the streets and addicted to drugs when he found himself in a hospital in White Plains. From there White was sent by health officials to Palisade Gardens, an adult home in Westchester where he received the support he needed to rebuild his life without drugs. White became involved with the Coalition for Institutionalized Aged and Disabled -- he is the president of the chapter in Palisade Gardens -- and works as an inspector for the local Board of Elections.

White credits the home for getting him back into the swing of things. "This place is not bad. ... I know for a fact that a lot of homes are a lot lesser," he explains.

But still White is ready to move on. He is tired of going to dinner only to find ground beef replaced by ground turkey, and ribs and pork chops pulled off the menu because of budget cuts. "I think I'm ready to go now," he said without any sense of anger or frustration. "I miss doing things for myself. I miss cooking, I miss choosing what I get to eat."

White imagines himself in a one-bedroom apartment, perhaps a studio, anything to get him back into society and making his own choices. He still wants some of the counseling and support he gets from the state. For now at least, no appropriate option is available.

"I've got nothing bad to say about this place. They helped me," White said. But now if I could get a little bit of help to get out of here. ... I'm ready to move on."

At this point the hopes of White and hundreds of other patients rest in the hands of the state.

Health Care, Development Dominate Debate in Forest Hills

With its pleasant residential neighborhoods and fairly affluent population, District 29 in Queens avoids many of the ills facing the city's grittier areas. But like so many Americans, residents of this area have major concerns about health care.

The closing of hospitals and the delivery of medical services to the district's residents has been a key issue in the campaign for the City Council seat currently held by Melinda Katz, who decided not to see re-election and is running for city comptroller. Like people in other parts of Queens, residents of the area also are concerned about development.

The race features six Democrats: Heidi Chain, a lawyer with the city Department of Finance who received the 2008 New York Police Department Woman of the Year award; Albert Cohen, an immigrant from Tajikistan, who has his own law practice; Michael Cohen, who represented Forest Hills in the State Assembly from 1999 to 2005; Melquiades Gagarin, media manager for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund; Karen Koslowitz, a former City Council member; and Lynn Schulman, the chair of Community Board 6.

The winner of the Sept. 15 primary will run against the Republican candidate, Bartholomew F. Bruno, in the Nov. 3 election.

A Hospital Shortage?

In a span of 12 months, three hospitals in Queens have closed. One, Parkway Hospital, the city's only privately run hospital, was in District 29. (The other two were Mary Immaculate Hospital and St. Johns Queens). In the wake of the closure, residents of Kew Gardens and surrounding neighborhoods worry about a shortage of hospital beds and long waits at emergency rooms.

Heidi Chain

The volume of patients at Forest Hills Hospital has increased by 40 percent from a year ago, and the number of patients who are being admitted is up about 12 percent, according to public relations spokesman for Forest Hills Hospital Terry Lynam.

"They [hospitals] have people practically in bunk beds," said Barbara Stuchinski, a local resident.

Chain expressed dismay that the hospitals ever were allowed to close. "They bail out banks, we bail out General Motors, and we didn't bail out the hospitals to protect the folks in Queens," she said, her tone reflecting her disbelief. To help fill the gap, she would establish a service helpline to provide immediate round-the-clock help.

Melquiades Gagarin

The closing has had very real effects, according to Schulman, who works at Woodhull Medical Center in Brooklyn. "The number of ambulance tours in the districts have gone down so response time has gone up," she said. She hopes to open an ambulatory care center in the district to provide immediate assistance to residents.

In Michael Cohen's view, the closed hospitals must be replaced. "Either reopen those hospitals or open new facilities," he said. "On a temporary basis, we should expand a walk-in clinic, but that is no substitute for a hospital." Money for this could come from a stock transfer tax or a bond issue approved by voters.

Albert Cohen would try to reduce the burden on the hospitals by promoting preventive care. To accomplish this, he would invest in medical screenings to identify health concerns before they send an individual to the emergency room.

Rezoning the District

The recently approved rezoning of Forest Hill's Austin Street won applause from the candidates. Austin Street has become the trendy shopping destination for residents with big name stores such as Sephora and Barnes & Noble. The rezoning is intended to promote more residential development in the already crowded area.

Karen Koslowitz

Koslowitz, who has very distinct red hair, has been credited with shutting down strip club Runway 69 when she last served as council member. That helped create the current boom in development on Austin Street.

While Michael Cohen supports the overall rezoning, he has concerns about parking. "I am critical in the plan with the amount of mandatory parking that would be provided," he said.

Albert Cohen has also focused on parking problems in the district, holding a press conference to complain about angled parking spaces on 108th Street and the ticketing of driver who don't back into their spot.

On another development question, five of the candidates have endorsed the rezoning to limit sizes of building in the Cord Meyer area, but in a debate, Albert Cohen opposed the change. He said the new limits are aimed at the Bukharian community, many of whom have built large homes in that neighborhood. According to TimesLedger newspaper, the rezoning " has highlighted the tension between the Bukharians and non-Bukharians."

Gagarin would change zoning rules to allow for the creation of more schools.

As the area has boomed, rents have increased. Many resident worry about the expense and fear they might have to another neighborhood. Schulman, vowed to advocate for legislation that would let the City Council set rent guidelines, as opposed to having the state legislature do it.

In the Home Stretch

The campaign has been largely free of acrimony, as the candidate compete for money and support in advance of primary day.

Albert Cohen

Chain, who has the support of many police groups, leads in fund-raising, but there's a bit of a twist. Unlike her opponents -- and the vast majority of city candidates apart from Mayor Michael Bloomberg -- she is not participating in the public finance system, reportedly because she does not think candidates should take taxpayer money in these tight economic times. She has raised almost $207,000 in private donations -- with more than $125,000 of that coming from herself.

Now it turns out Chain may not have saved the city any money afterall. City Hall has reportedthat Chain's fundraising and not particpating in public financing "triggered a provision of the Campaign Finance Board program that gives opponents an additional $95,000 in public funds. That equals $7,000 more than she would have received had she joined the program and received matching funds for raising the maximum amount from others."

Among the others, Koslowitz has raised the most private money -- $93,730, followed by Schulman with $87,260, Michael Cohen with almost $46,000 and Albert Cohen with about $43,000. Gagarin trails with $17,599.

Lynn Schulman

Schulman, who ran unsuccessfully for the seat eight years ago, has the backing of the Working Families Party and the Service Employees Union this time around. The

Times has endorsed her as well.

Koslowitz, who has the Independence Party nomination, is backed by City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, who has campaigned with her.

Chain has support from several police groups

This article was written under a partnership between Gotham Gazette and the Baruch College's Department of Journalism and Writing Professions.

Closed Hospital Plays Key Role in Jackson Heights Race

Any number of potential City Council candidates saw their plans thrown into turmoil in late 2008 when the City Council voted to extend term limits and allow incumbents, including Mayor Michael Bloomberg, to run for a third term in their respective New York City offices.

Helen Sears

The move whittled away a number of challengers in District 25, which encompasses Jackson Heights, Corona and East Elmhurst. But two -- Daniel Dromm and Stanley Kalathara -- have remained in the primary race to challenge incumbent Helen Sears. With a spirited primary race underway, the conventional wisdom -- that an incumbent always wins -- might not hold true here. The winner of the Democratic primary will face Republican Mujib Rahman in November.

The diverse district faces an array of problems, including a lack of health facilities, development and overcrowded schools. While the candidates all seek to address those issues, their platforms emphasize different areas. Sears, who was first elected in 2001, is taking on the district's health care dilemmas; Dromm, a schoolteacher and union leader who is also a gay activist, is focusing on education reform; Kalathara, a lawyer and businessman, wants to clean up the neighborhood by improving the quality of life and attract dollars that would otherwise be spent in Manhattan.

The Hospital Closing

The fault line of this campaign is the recent closing of St. John's Hospital. When Caritas Healthcare, the company that ran St. John's Hospital and Mary Immaculate Hospital, also in Queens, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy early in 2009, the hospitals were unable to keep their doors open. Even before Caritas' bankruptcy, St. Johns had been plagued by a shortage of beds and outdated equipment.

Consequently, the 100,000 patients serviced in their emergency rooms must now go to other medical centers. Residents of Corona, East Elmhurst and Jackson Heights have to use the already strained resources of the two remaining neighborhood hospitals, Holliswood and Queens Hospital Center.

Sears' opponents hold her responsible for the closure of St. John's. Sears maintains that she moved quickly to keep the health center open. New York State extended money to the hospital, but said it could not make regular contributions.

"She only showed up at a protest at the very end. She should have started [taking measures to avoid this] since her election," said Dromm.

Kalathara said, "I am not going to play the blame game." But he cited his concern about the impact of any re-emergence of swine flu this fall, noting that the two remaining hospitals serving the densely packed district were already seeing a doubling in cases

Planning for the Future

Sears, a former healthcare professional, has spent a great deal of time defending her past two terms in local debates, rather than speaking of her aspirations for a third term. During her two terms, she said, the Corner Care Pavillion opened as a health center for neighborhood residents. Now she said, it will add a woman's health clinic. "This district is incredibly diverse -- every country in the world is represented here," she said. "A woman's clinic will bridge cultural differences and will provide and teach women how to seek healthcare."

Daniel Dromm

Interviewed in a restaurant where the waitress speaks Spanish, Dromm cites his experience in advocacy and community affairs. "I recently organized a documentary screening about Muslim Sikhs to be shown in a Jewish center," he said.

His self-titled Dromm Plan vies to improve life for community residents with measures such as ending the self-certification practiced by real estate contractors and reducing noise pollution by pushing through legislation. He also proposes measures to help the area's many immigrants, such as addressing the employment scams which they too often face. "A center for day-laborers where they could meet potential employers would create safer situations and ensure union jobs by bringing immigrants into them," he said.

Kalathara, a self-made man who prides himself on his awareness of neighborhood difficulties, holds his interview in his neighborhood law office where the clientele are of Indian and Latino origin. He said he wants to address foreclosures, job loss and safety on Roosevelt Avenue and Junction Boulevard. "Installing lights, on stretches of blocks that often go without them is another plan to ease crime," he said.

He plans to push legislation to secure daily garbage pickup for his district and proposes the widespread use of charter schools to improve the education standards in city schools. "I will donate 10 percent of my salary to give funds to the most worthy community organization or school in this district," he said.

Stanley Kalathara

Kalathara extols his campaign as "a message of belief, opportunity." Holding himself up as an example of the American dream -- Kalathara worked his way up from an Indian immigrant-busboy to a lawyer -- he said, "I want to set an example for others." Indignant about the economic disparities between his district and many Manhattan neighborhoods, he said, "Queens is not a second class world. I want to make sure Queens citizens are treated first class,"

On the day of his interview, Kalathara was fighting to stay on the ballot. He sat, confident behind his desk in his Queens law office. "I've sent one of my lawyers to handle the case," he said. When questioned about the validity of the signatures on his ballot petitions, he said simply that Dromm, who had challenged them, "is a sour grape."

Votes for Immigrants

In this district of many immigrants, there is debate about Resolution 245, which would give non-citizens the right to vote in New York City elections. Dromm strongly supports the act, while Kalathara merely agreed. At a recent debate, Sears had no opinion to give, saying, "I'm here to tell you that I'm not sure where I'm on this. I haven't given it much consideration."

The passage of resolution 245 would have an enormous impact on the political landscape of New York City, particularly in this heavily immigrant Queens District. Estimates place those who are of age but cannot vote in New York City elections at 1.3 million, easily more than one-eighth of the city's overall population.

Explaining his support for the resolution, Dromm said, "There should be no taxation without representation. This is a basic American tenant, and it's the key to ones destiny."

The Anonymous Charges

On a far murkier level, controversy also has arisen over anonymous leaflets about Dromm that some have characterized as part of a "homophobic smear campaign." The leaflets reportedly allege that, as a 16-year-old, Dromm was arrested for prostitution. He has said he was simply kissing his boyfriend but that, in the 1970s, " being gay meant that you could be put away against your will in a mental institution."

Kalathra and Sears both condemned the attacks, although Sears has been criticized for not speaking out sooner and more forcefully against the advertisement.

Money and Support

Sears remains the campaign heavyweight in terms of budget. She leads with $128,493. Dromm is second in funds with $103,958 and Kalathara with $92,489.

Dromm has endorsements from the Working Families Party; Service Employees Union Local 1199, which represents healthcare workers; the United Federation of Teachers, as well as by local politicians including state Sen. Tom Duane and three City Council members from Queens.

An Outer Borough Drought

Photo (cc) tatoodjj

This story was done through a partnership between The Huffington Post's Eyes and Ears citizen journalism program and Gotham Gazette. Gotham Gazette reporter Courtney Gross wrote the piece using stories from New Yorkers gathered through The Huffington Post and Gotham Gazette. Sign up here to join Huffington Post's citizen journalism team covering New York to be part of more of these stories.

Fruit stands are Manhattan's new hot dog vendor, minus the mustard and ketchup.

Their street corner takeover has sparked some New Yorkers, like Upper East Sider Jamie Kayam, to carp that their neighborhood is oversaturated with apples, bananas and overly ripe white cherries.

"In NYC, buying fruits and vegetables has never been easier!" Kayam wrote in an e-mail to Gotham Gazette and The Huffington Post. "When recently discussing life in the city with some friends, a key complaint that came up was that there are too many fruit stands in Manhattan!"

Across the river, Kayam's plight might be a blessing.

The Upper East Side has one of the highest concentrations of food retailers in the city, according to the Department of City Planning. The neighborhood ranks third in the number of grocery stores per capita, boasting more than 22,000 square feet of strictly supermarket space per 10,000 residents, according to the department.

But out of Manhattan, greens get elusive. In the South Bronx, residents have about half of that supermarket space. In Brooklyn's Bedford Stuyvesant, 82 percent of retailers are unlikely to sell fresh fruits and vegetables, and in some areas of Upper Manhattan that number increases to 90 percent, according to city planning.

The Huffington Post and Gotham Gazette asked you how far you travel to get fresh fruits and vegetables. Many of you said veggies are ripe for the taking in your neighborhoods. But a majority of those of you who responded, almost two thirds, live in Manhattan, brownstone Brooklyn or other affluent areas of the five boroughs.

Those outside of these areas may not find a fruit flood, but a produce desert.

|

|

|

|

|

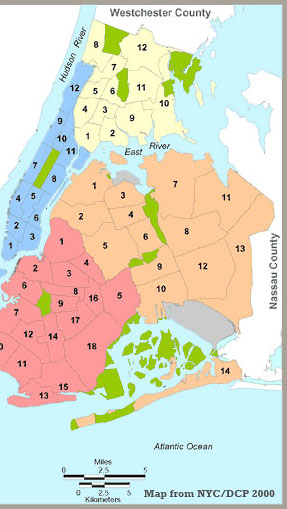

This map uses data from the city's Going to Market report released last year. Rollover a district to find out how many supermarkets there are and how that compares to the number of residents.

A Borough Away

Chelsea is an agricultural Atlantis, says resident Steve Panepinto.

"There's a wide selection of fresh fruit and vegetables on virtually every corner not to mention in the half dozen supermarkets that are within three to four blocks of my apartment," he told us. (Chelsea actually has the highest concentration of grocery stores in the city, according to city planning.)

About 100 blocks north it's another story.

"I live in the West Harlem area, and it is incredibly difficult to find quality fruits and vegetables," writes Erin Barker. "It's a big problem. Even when stores have this stuff, it's usually not in good shape -- bruised or not usable. I think it is more difficult in my neighborhood than it is in wealthier areas of Manhattan that have more upscale grocery stores."

Barker, according to the city, is on point. The lower the median income, the harder it is to find fresh fruits and vegetables. (Chelsea's median household income is more than $100,000, while West Harlem's is about $30,000.)

The discrepancy, according to Ben Thomases, the Bloomberg administration's food policy coordinator, explains why the city is targeting areas in Upper Manhattan, central Brooklyn and the Bronx to grow (pun intended) access to fruits and vegetables. It's pushing for produce on the shelves of corner bodegas, has issued 1,000 green cart permits for specific neighborhoods and is now working on financial and zoning incentives to get more supermarkets into certain areas.

"A lot of low-income communities in Upper Manhattan and the outer boroughs were decimated in the '70s and early '80s," said Thomases. "At that time, naturally, a lot of supermarkets left. When the communities were rebuilt, for a mixture of reasons, the supermarkets didn't really come back."

The administration has already kicked off its financial package, which includes tax abatements for new supermarkets and for those that want to renovate or expand. The city will provide a sales tax exemption for anything related to expanding or constructing a grocery store, from cash registers to two by fours. It also is offering a mortgage recording tax waiver.

To root even more supermarkets in needy neighborhoods, the city's Planning Commission proposes to allow developers to build bigger spaces if they include a supermarket in their plans. If a large mixed-use development has a supermarket on its bottom floor, the city will support the addition of the same amount of square feet of residential space, in effect adding thousands of square feet to the structure. City officials say they will also lower the amount of parking spaces required for supermarkets and are allowing larger grocery stores in manufacturing areas. Currently, these zoning proposals are under review and should be voted on by the City Council by the end of the summer.

Getting Fresh Foods

So far, the city is aiming low. A success to Barry Dinerstein, a senior planner at the city's Department of Planning, would be another 15 supermarkets sprinkled throughout the city's highest need areas in the next few years.

That goal is unlikely to alter Keri Roberts's two-mile bike ride from her Windsor Terrace apartment to the "local" Costco.

"My biggest complaint about living in New York is how hard it is to get fresh produce," Roberts, a technical writer and 16-year Brooklyn resident, said.

For many like Roberts, it's not just about proximity, but cost. If you're on a fixed income, the corner bodega's fruits, while close to home, come with an inflated price tag. "It's just so expensive," said Roberts.

So, some New Yorkers walk (a.k.a. wince and make like it's an added health bonus). Oliver Noble, who is on fixed income, travels 25 blocks from his Park Slope apartment to a vegetable market. Last week, he told us, those blocks cut his produce cost at least in half. He got green peppers for 69 cents a pound -- a bargain from the usual $1.99 a pound.

At least for the next few months, the city's green markets can be a summer savior. The Council on the Environment of New York City, a city-affiliated nonprofit, is running 49 greenmarkets this year across the five boroughs, bringing fresh vegetables (at least temporarily) a lot closer to home for scores of neighborhoods, said Sabine Hrechdakian, the council's special projects and publicity manager. Of those, 23 accept food stamps.

But only 18 of the markets are open year-round, seriously depleting the fresh food supply come the colder months.

Hence, the city's new pro-supermarket campaign.

"We recognize a farmer's market does not take an area that is really underserved by fresh produce and make it all better," said Thomases. "They generally operate one or two days a week. People need to shop seven days a week."

People like Michael Paone, a Crown Heights resident who heads to Park Slope's food cooperative for affordable veggies via bike or two subway transfers. Fresh Direct or a quick and accessible purchase at the local bodega is out of his price range, leaving him with little options.

"It's a shame to me that the main place I can afford (monetarily and biologically) to patronize is not in my neighborhood," Paone told us. "One day, soon, I hope this will not be so."

Public Hospitals in Critical Condition

Four clinics are set to shut, four mental health programs in New York City public schools won't be around next year, and three satellite pharmacies are about to fill their last prescriptions.

These are just some of the measures the city's Health and Hospitals Corp. is taking to address a budget hole that could grow to $1 billion in 2010. And more cuts are coming, said corporation President Alan Aviles.

Call it a side effect of being a public hospital system, but the Health and Hospitals Corp. has been consumed by a tsunami of unfortunate fiscal tidings. Several detrimental cuts from the state (the state's Department of Health argues otherwise) and a steady rise in the uninsured, corporation officials said, has forced the 11-hospital network and its scores of outpatient clinics to restructure -- floating the possibility of a consolidation of services and additional clinic closures.

At a City Council budget hearing Wednesday, Aviles said the corporation is grappling with how to close a $316 million budget gap for this year alone. It has already earmarked measures, such as closing clinics in Sunnyside and Springfield Gardens in Queens, a clinic in the High Bridge section of the Bronx and another in Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn, which would save $105 million. Additional budget actions, Aviles said, are under review.

But the corporation faces structural, long-term fiscal problems that its leaders attribute to restructured state Medicaid reimbursement rates, unreliable federal funding streams and a growing population of patients who can't afford to pay. The cuts alone will not remedy those problems.

Dire Straits

No one can deny the city's public hospital system, which sees 1.3 million New Yorkers a year, is in critical fiscal condition.

"HHC has problems in the few hundred million at the moment because of the state cuts, but when you look at its financial plan going out, its problems are in the billion dollar range," said Mark Page, the director of the city's Office of Management and Budget at a recent City Council hearing. "And how that gets addressed in the next few years, I think it's going to be a huge challenge for New York City and HHC."

Not surprisingly, it is difficult to determine who is to blame. The corporation, say officials, is pointing at the state, specifically its revision of Medicaid reimbursement rates and its distribution of federal Medicaid funding streams, including money it received from the federal stimulus package.

The Health and Hospitals Corp. says it lost out.

"The state has discretion with those dollars, and they were largely used for gap closing," said Aviles of the state's own budget woes. "They were certainly not used to offset further cuts (at the Health and Hospitals Corp.)."

With the aim of restructuring its rates for reimbursing hospitals, clinics and doctors for treating low-income Medicaid patients -- a calculation that still relied on figures from the 1980s -- the state, over the course of two years, approved new formulas for the disbursement of Medicaid dollars. The new formulas, according to state officials, would not only bring the reimbursement rates up to date, but also reflect the type of care New York's patients actually received. State health department officials said the state had been overpaying for inpatient care and underpaying for outpatient care as the health industry refocused its concentration on preventative medicine. Under the new rates, say state officials, the corporation could take advantage of higher outpatient rates by moving some procedures to their clinics.

The implication of the new rates, said Deborah Bachrach, deputy commissioner for the Office of Health Insurance Programs at the state Department of Health, was a hospital would get paid more if it did more. The state, she said, should not pay the same rate to clog a nosebleed that it pays for cardiac care.

"Our first obligation is to get people covered," said Bachrach. "And the second obligation is to buy the right care in the right setting at the right price."

The Health and Hospitals Corp. does not see the revision that way. Aviles told the City Council that the corporation would lose $45 million in Medicaid funding this year, $109 million in the next fiscal year and $150 million in fiscal year 2011.

Much of the corporation's funding comes from two other Medicaid federal funding streams, which are distributed by the state. This year, the corporation has received about $416 million so far from these streams, according to corporation officials, half the annual $838 million it received, on average, over the past five years. More is likely to come from the federal government later this year, Aviles said.

The state does not contribute to at least $300 million of that Medicaid funding. Half is from Washington, and the other half is from the city.

The corporation's primary patient population is poor and uninsured, and under its charter, it can turn no one away. Meanwhile, the number of uninsured patients continues to rise, increasing 8 percent from 2007 to 2008. This makes it particularly dependent on outside funding streams and government subsidies.

Of the corporation's $6.7 billion budget, little comes from city tax dollars -- about $89 million. That too could be cut by $3.5 million, according to the mayor's executive budget proposal, threatening child health clinics.

Who to Turn To?

At a budget hearing on Wednesday, Councilmember Helen Sears sang the corporation's praises.

"How do you get through these state cuts and federal cuts?" the Queens legislator asked. "Your cuts get deeper and deeper and you manage to give quality care."

Some fear that will not happen for long.

As other nonprofit, private hospitals across the city close their doors, like Mary Immaculate Hospital and St. John's Queens Hospital, City Council members fear patients will inundate the corporation's facilities, further taxing the system.

"They are incredibly important part of the safety net in New York City and anything that is happening that is going to push them to reduce their ability to serve uninsured people in their outpatient departments is going to be devastating," said Elizabeth Swain, chief executive officer of the Community Health Care Association of New York.

As for the city, a Bloomberg administration spokesperson said in an e-mailed statement: "HHC faces fiscal challenges as most healthcare providers do and addressing these challenges will likely involve the corporation, the city, the state and the federal government -- at a time when needed reforms of the health care system are a national topic of much debate."

In 2004, Mayor Michael Bloomberg allocated $200 million to the city's public hospitals to help reverse year's of neglect by the Giuliani administration. It's unlikely they would do the same again with their own fiscal problems. Overall, both the administration and the council have little influence over the structural deficit the corporation faces.

Currently, the corporation is pressuring city officials to lobby state legislators for funding to stave off the budget gaps down the line. That will not halt their current restructuring, which, Aviles said, would most definitely result in a drop in services.

"It will require looking at the traditional approach that all hospitals can be all things to every community," said Aviles. "To some extent we may have to consolidate some of our services in some of our facilities so that we can maintain those essential services and access to those services, but deliver them as efficiently as possible."

City, State Do Little to Address Female Genital Cutting

Image by Gotham Gazette

For Angela Montague, it began with a young woman from the West African country of Guinea. In February 2008, Montague, a licensed clinical social worker and the assistant director of social work at the Metropolitan Hospital Center in East Harlem, received a referral from a doctor in the hospital's family planning clinic. A 19-year-old patient had come in complaining of abdominal pain and then broke down crying.

The young woman traced her physical and emotional pain to when she was 8 years old and the women in her community in Guinea had gathered to perform a rite of passage on her - namely, cutting off her clitoris.

"She came to see me the same day as her physical exam," Montague said. "She was clearly experiencing symptoms of post traumatic stress disorder. She had regular nightmares about the day she was cut, and she had difficulty concentrating because the memories would continually resurface. She even feared groups of people because it reminded her of the group of women who held her down while the cutting was performed."

Known alternately as female genital cutting (FGC) or female genital mutilation (FGM), the removal of all or part of the external female genitalia is practiced across cultures and religions in parts of Africa, Asia and the Middle East. It is generally performed by women on girls as part of the transition to adulthood. The World Health Organization estimates that between 100 million and 140 million women and girls worldwide have undergone FGC. In the United States, estimates suggest that the number of women and girls who have undergone FGC or who are at risk grew by about 35 percent between 1990 and 2000 - from 168,000 to 228,000. The New York metropolitan area is estimated to have the highest number of women and girls affected by or at risk of undergoing genital cutting in the United States: just under 41,000, according to estimates based on data from the 2000 census.

Montague saw the young woman regularly for counseling and began to receive referrals of other women in New York experiencing similar problems. When she spoke to her colleagues throughout the city about genital cutting, she discovered that many of them were not aware of the issue and that education on the health consequences of the practice was limited. And while some individual service providers were working to support women and girls who had undergone cutting, a comprehensive structure for addressing the issue remained unrealized at both the state and federal levels.

In fact, neither the city nor the state government has taken concrete steps to address the practice or its effects, which can range from post-traumatic stress disorder to severe infections, painful menstruation and complications during pregnancy and childbirth.

What the Government Is Not Doing

New York is one of 17 states that have passed legislation criminalizing the practice of FGC on minors. The state law, which is modeled on federal legislation that was also enacted in the mid-1990s, identifies both the person who performs the cutting as well as the parent or guardian who consents to it as being "guilty of female genital mutilation."

The law also required the state Departments of Health and Social Services (now the Office of Children and Family Services) to establish "education, preventive and outreach" activities in communities that traditionally practice FGC in order to inform them of the health consequences of the practice and the provisions of the state law.

Very little has been done, however, to implement either part of the law. The last sustained education and outreach activities took place 10 years ago in collaboration with the women's advocacy organization RAINBO, said Mary Applegate, who coordinated the project when she was the medical director in the New York State Department of Health's Bureau of Women's Health. The bureau's current women's health coordinator, Margaret Allen, said that she is not aware of any ongoing activities on FGC at the state level.

The New York City Health Department also reported that they have no information on FGC.

A bill that is currently before the New York Senate Health Committee would require the state Department of Health and the Office of Children and Family Services to produce an annual report to the governor and state legislature on their activities addressing FGC. Versions of the bill have been making their way through the Assembly since 1995 but have repeatedly died in the Senate. The bill was reintroduced in January 2009 by Assemblywoman Barbara Clark of Queens.

"As far as we know, the state is not undertaking activities to address this issue," said Jessica Gormand, Clark's legislative director. "Part of the motivation for putting this bill forward was to bring this to light."

And on the law enforcement side, no criminal case has ever been brought using the New York law, or other state and federal laws, on genital cutting, said Taina Bien-Aimé, executive director of the human rights organization Equality Now, which works to end the practice worldwide.

The lack of activity in the state mirrors the situation at the federal level. Federal law also criminalizes the practice of FGC on minors and charges the Department of Health and Human Services with conducting outreach and education to communities and service providers. The department worked with RAINBO to produce and distribute a curriculum for health care providers on FGC in the late 1990s and held a few community workshops, but no regular activities have taken place since 2000, said Wanda Jones, deputy assistant secretary for health and director of the department's Office on Women's Health.

The small amount of funding that was allocated to these activities in the 1990s also has largely disappeared, Jones added.

The lack of government activities on FGC in the United States comes at a time when governments in Africa and Europe are stepping up their efforts to prevent and respond to cases of FGC through legislation and targeted social services, said Bien-Aimé.

"The United States has fallen behind many European and African countries in addressing female genital mutilation," she said. "There is a fundamental ignorance on the issue and a limited political will to recognize that girls are at risk here."

A Grassroots Effort

Without leadership or resources from the city, state or federal government, a handful of community-based organizations, like Sauti Yetu Center for African Women in New York, and individual service providers like Montague have taken on much of the work of preventing FGC here and responding to its effects.

In New York, Sauti Yetu is the only community-based nonprofit working specifically on FGC, said Asmaa Donahue, senior program officer at Sauti Yetu.

As part of its response efforts, Sauti Yetu trains health-care professionals, medical students and social service providers working with African communities to give medically appropriate and culturally sensitive care to women who have undergone FGC. In many cases, service providers who come across FGC in their work will also approach Sauti Yetu to develop a partnership. Montague, for example, worked with Sauti Yetu earlier this year to organize a panel on FGC and medical care at Metropolitan Hospital Center, and she is also working with them to organize a session on FGC for the hospital's staff.

At the federal level, Health and Human Services has begun to re-engage with community activists and service providers to see how the federal government might support prevention and response efforts, said Jones. In 2006 and 2007, for example, the department's Region II Office of Women's Health, which includes New York, participated in meetings organized by Sauti Yetu to discuss gaps in addressing FGC in the region. The participants included state department of health officials, nonprofit organizations working on reproductive health and sexual violence, and women from immigrant communities. Sauti Yetu also continues to lobby the federal government for funding to support community-based work on FGC, said Donahue.

There are currently very few organizations spearheading prevention efforts in the United States. Organizations such as Equality Now and the Tahirih Justice Center near Washington, D.C. seek to raise public awareness and support women and girls seeking asylum due to the threat of FGC in their home countries.

At the local level, Sauti Yetu engages communities in discussion about the practice and is cultivating a network of African women working to end FGC in their own communities. The New York area, though, does not yet have many vocal, grassroots advocates on this issue, said Donahue.

Several service providers noted that prevention efforts can be successful only when the communities are involved as leaders.

"Activism in the 1990s focused on criminalizing FGC, and communities [that traditionally practice FGC] were left out of the policy conversation. This led to a backlash," said Donahue. "They saw themselves being portrayed as barbaric in the media and they felt under attack. Women felt stigmatized rather than empowered to address the issue."

Service providers fear that a renewed focus on law enforcement could drive the issue further underground and prevent women and girls from seeking help either to prevent FGC or to address its effects, said Jones.

Still, at both the federal and state levels, little promises to change soon. FGC does not appear to be on the agenda of relevant state or city agencies in New York, and in a city of millions, an issue facing thousands of immigrant and refugee women and girls can easily remain marginalized. Despite the numbers, though, the need to address the practice remains.

"New York is a city of immigrants so service providers have to be prepared to provide culturally sensitive and appropriate services on practices like FGC," said Montague. "These women need a safe place to go."

Alyson Zureick is a freelance writer based in New York.

Council Takes a Bite Out of Bed Bugs

Photo from wiki commons

The City Council tried to bite bed bugs back Wednesday when it unanimously approved legislation spurring the city to investigate the epidemic.

The bill requires the city form a task force to make recommendations on how to stop infestations currently ravaging apartments citywide.

The council also approved legislation requiring the registration of debt collectors, the reinstatement of a waterfront advisory board and an increase in fees for waste transfer station operators.

Banning Bed Bugs

They crawl through walls, from apartment to apartment, devastating buildings and sometimes blocks. Bed bugs, which the city thought pesticides had vanquished decades ago, are making a comeback.

In an attempt to exterminate them, the City Council approved legislation (Intro 57-A) that sets up a bed bugs task force to investigate infestation trends and draft recommendations to eradicate the pests. The bill, sponsored by Councilmember Gale Brewer, was pared down during the legislative process. It had initially banned the sale of restored mattresses.

The epidemic has grown in the city over the last few years, said Brewer. According to the council, there were 377 bedbug-related violations in 2004, compared to two in 2002. Last year, Brewer said, the city conducted 9,000 housing inspections related to bed bugs.

"Getting bed bugs is a personal nightmare," said Brewer. "It's a financial nightmare."

Infestations aren't deadly, but they can ruin furniture, especially mattresses, and can prove very costly.

The task force will include representatives from the departments of consumer affairs, health and mental hygiene, sanitation, information technology and communications, and housing preservation. It will also have an exterminator, entomologist and community health professional on board.

The task force will look into infestation treatments, tracking, disposal of infested items, and training and education for pest management professionals, city employees and the general public.

Council Speaker Christine Quinn said this would not be the last bill the council votes on regarding bed bug infestations.

Another bill currently under consideration by the council would require that old mattresses be put in plastic bags when thrown out.

Buying Debt

Purchasers of second-hand debt will now be required to register with the Department of Consumer Affairs and follow the city's collection regulations under legislation passed unanimously by the City Council.

The vote was 46 to 0.

The bill ( Intro 660), sponsored by Councilmember Daniel Garodnick, is in part a response to a 70 percent increase in complaints to the Department of Consumer Affairs between 2006 and 2008. Garodnick said the number one topic of complaint at the department is unlicensed debt collectors.

Spurred by the current financial crisis, agencies have purchased debt from licensed collection companies, but they have failed to get registered themselves, Garodnick said. This creates confusion for the consumer, who is all of a sudden receiving collection notices, phone calls and even court summonses from an unfamiliar agency.

These collectors have made an industry out of buying debt, said Councilmember Leroy Comrie, the chair of the council's consumer affairs committee.

In addition to requiring registration, Garodnick said, the bill will force the debt collectors to identify the original creditor, itemize the money owed, provide background information on the obligation and give confirmation in writing when the debt is settled to avoid consumers being charged with collections twice.

Garodnick said 300,000 debt cases have been brought against New Yorkers.

Protecting the Waterfront

To revive an agency that has been defunct since the Dinkins administration, the council approved legislation ( Intro 867-A ) reauthorizing the formation of a waterfront advisory board.

The board will be charged with reporting to the council and the mayor twice annually with recommendations on how to better utilize the city's 578 miles of waterfront. The board will be required to look into recreational use of the waterfront.

Increasing Waste Fees

The City Council approved legislation ( Intro 840) to raise fees for permits for operators of waste transfer stations.

For more on solid waste management in the city play The Garbage Game.

The city will increase fees for operators at non-decomposable waste sites from $3,500 to $7,000 annually. For station operators who deal with decomposable waste, annual fees will be raised from $6,500 to $13,000. Fees have not been raised in two decades, according to the council.

The legislation would also create a $7,000 fee for solid waste container facilities that operate two forms of transportation, such as both truck and rail.

A Food Policy for New York

Photo (cc) the T bone

Increasing the availability fresh produce, like these apples at Union Square Greenmarket, is one small piece of New York's public health policy.

Food policy, nutrition and public health have played a central and often contentious role in the Bloomberg administration's agenda for the city. Achieving the goal of a healthier New York City has led the mayor to employ both legislation and executive order. Now Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer has joined the push to increase the availability of healthy foods such as fruits and vegetables in an effort to improve public health.

"We need a paradigm shift in the way New York thinks about food. For too long, decisions about food have been made on the federal level or by private parties," Stringer said.

The city's food and public health policy has had three major parts: increasing the availability of healthy food, reducing the prevalence of unhealthy food and adjusting the public's behavior so people eat a better diet. Stringer's proposal takes a larger scope than previous initiatives and offers a comprehensive plan for the city. The report focuses on using tools such as zoning and tax abatements to ensure the city's "food security" and eradicating its "food deserts."

Neighborhood Food Shortages

In April 2008 the Department of City Planning issued a report detailing the intersection of demographics, geography, food policy and public health. It concluded areas underserved by retailers selling fresh food, such as the Bronx, central and eastern Brooklyn, far eastern Queens and Harlem, have above average rates of diet related diseases.

Currently, an estimated 3 million New Yorkers live in "high-need neighborhoods," defined by a lack of supermarkets and a prevalence of diet-related health problems. These areas lack food security, meaning that people who live in them have difficulty getting "nutritious and affordable food." An estimated 750,000 city residents live in "food deserts" -- areas more than five blocks from a supermarket. Often food deserts are located in low-income and minority communities with a prevalence of diet-related disease, such as obesity and diabetes.

Increasing rents and tight profit margins have led to a wave of supermarket closings across the city, exacerbating existing problems. Many of the supermarkets have been replaced with drug stores, which sell the unhealthy foods at the root of weight-related health problems as well as the medications used to treat them. Pharmacies, convenience stores and discount stores, which sell processed foods, have become the primary food retailers in some neighborhoods.

The city has taken several steps to reverse this trend, including the healthy bodegas initiative, which tries to encourage the small neighborhood stores to stock low and reduced fat milk as well as fruits and vegetables. In February 2008, City Council passed the Green Carts bill to allow more mobile fruit and vegetable vendors in low-income neighborhoods. Bloomberg and City Council Speaker Christine Quinn put forward the bill as part of the effort to make New York City healthier.

Stringer would build on these efforts. Under his report's recommendations, the city would continue to look at approaches to making fresh produce available outside of the traditional grocery stores and supermarkets, but also would take a more active approach to increasing the availability of healthy foods. He recommends the city create "food enterprise zones" to attract food retailers to underserved areas through zoning and tax incentives. The plan calls for public financing or micro loans to community food partnerships, allowing food vendors tax abatements under the Industrial and Commercial Abatement Program and exempting vendors from business taxes. It also suggested the New York City Housing Authority make provisions for food retailers in public projects.

Zoning for Food

Photo (cc) specialklikethecereal

Zoning regulations offer another policy option to increase the number of retailers selling healthy foods and stem the tide of closing supermarkets. The report suggests government agencies develop an integrated plan for city support of supermarkets, adjust land-use regulations influencing supermarkets, consider supermarkets' need during future rezoning and evaluate the possibility of supermarkets on city owned property. For example, the city might categorize retailers selling fresh fruits and differently from general food stores and so provide them with a density bonus or a permit for additional floor area exemption, according to Stringer.

Other officials have proposed ideas to discourage less nutritious fare. Bloomberg ordered that city restaurants stop selling food containing transfats and now reportedly is considering ways to reduce the sodium content in prepared and processed foods. In his budget for the coming year, Gov. David Paterson called for an 18 percent tax on sugary drinks, although the idea appears unlikely to pass.

City Councilmember Joel Rivera had suggested capping the number of fast-food restaurants through changed zoning laws. The idea did not go anywhere here, but last year, the Los Angeles City Council unanimously passed a bill to place a one-year moratorium on the development of new fast-food restaurants in South Los Angeles, a low-income minority area that has double the obesity rate of the city's wealthier areas. The legislation is intended to allow for the development of restaurants that serve healthier food and is confined to an area of the city with high instances diet related problems.

While the borough president's office indicated it would be open to explore restricting the proliferation of fast food restaurants, people there point out that any effort to limit fast food outlets must be supplemented with a drive to increase the number of healthy food outlets. Instead, Stringer's report emphasizes more market-oriented approaches to improve the city's food options.

For one, the borough president's office proposes eliminating tax subsidies for fast food restaurants. "We'll give you a tax abatement if your store sells Big Macs but not if you just sell the lettuce and tomato. It's time for government to step up to change how we approach the city's dinner plate," Stringer said.

The Industrial and Commercial Incentive Program was intended to keep businesses in New York City by offering a tax abatement or tax exemption for increased property value, which would gradually be incorporated over time.

In October 2008 the Industrial and Commercial Incentive Program was replaced by the Industrial and Commercial Abatement Program, which puts more restrictions on the incentives. It limits the areas in which businesses can receive benefits -- firms in a large part of Manhattan can no longer qualify -- but it does not go far enough for some who believe the incentives tip the commercial playing field toward big corporations who sell unhealthy food.

"It was great that in midtown Manhattan it was basically eliminated," said Allison Lack of Good Jobs New York, a public interest group. But, she continued, retail projects, including national fast-food restaurants, are still eligible for tax abatements in Harlem, the South Bronx and Central Brooklyn, areas that are low-income, minority and afflicted with above average rates of diet-related health problems. Stringer would like to see the programs updated to prevent national fast food chains, such as McDonald's and Dunkin' Donuts, from benefiting.

Supermarkets and grocery stores also are eligible for tax abatements, but despite this many have not applied. "Some have and some haven't," said Lack. Good Jobs New York has not yet been able to determine why more retailers have not taken advantage of the program. "We really don't know. It's something we're looking into," said Lack.

Any effort to limit, restrict or inhibit the fast-food industry would meet resistance. Fast food restaurants constitute a powerful lobby. Subsidies given to producers of unhealthy food have increased the amount these companies spend on advertising and lobbying, giving them an even more outsized influence on food choices. But as obesity and diabetes rates rise -- and the costs placed on government increase -- a number of city offices are looking to end the Big Mad attack.

Know Your Invasive Critters

|

QUAKER PARROT Myiopsitta monachus Also known as: Quaker Parakeet, Monk Parakeet Native home: Argentina Came to U.S.: Through Kennedy airport Threat: Utility companies say the birds' huge nests can threaten electricity transmission and even lead to blackouts. Government action: In New York, Con Ed has tried to dismantle nests and has discussed building platforms to entice the birds away from power lines. Other states, though, have adopted more draconian measures. |

|

COMMON REED Phragmites australis Native home: North America How it got here: The opportunistic reed has spread everywhere. While degradation of wetlands gets much of the blame, some scientists believe a hardier strain of the plant, native to Europe, may be adding to the problem. Threat: Crowds out other plants, depriving birds of plants needed for feeeding and nesting. Government action: The city has a plan to reduce some nitrogen discharges into marshes. Many environmentalists believe the city must adopt other measures to protect its wetlands from phragmites and other threats. |

|

ZEBRA MUSSEL Dreissena polymorpha Native home: Russia and European waterways How it got here: Commercial fishing boats and cargo ships transfer foreign species like the zebra mussel to new waters by dumping contaminated ballast water. Threat: In addition to making some native species nearly extinct, zebra mussels colonies can be so dense that they clog intake pipes at water and power plants. They have also contaminated the water at treatment facilities. Some argue, though, they aren't all bad, because they consume bacteria and decrease water contamination. Government action: As of Sept. 30, thanks to a lawsuit brought by New York and several other states against the Environmental Protection Agency, it will be illegal for ships to dump untreated ballast water. A bill regulating the cleanliness of ballast water is stalled in the U.S. Senate. |

|

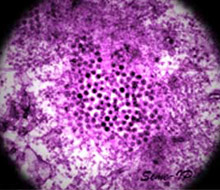

WEST NILE VIRUS Virus of the family Flaviviridae Native home: First detected in Uganda in 1937, later found elsewhere in Africa, the Middle East and Europe. How it got here: Believed to have come in through LaGuardia airport, possibly in a mosquito or infected passenger. Threat: An encephalitis disease, it can make people very sick and can be fatal, particularly for the elderly or people with compromised immune systems. It has also killed many birds and can affect other animals as well. Government action: Use of insecticides to kill mosquitoes and their larvae. Public education campaigns to help people avoid mosquito bites and remove standing sources of water. |

|

BED BUG Cimex lectularius Native home: Europe How it got here: Brought by early colonists from Europe. Threat: They bite! Severe infestations can mean the loss of mattresses, furniture, clothing, etc., because the pests are so tricky to eradicate. Government action: The City Council is considering legislation that would require used mattresses be labeled and put in plastic bags when discarded. The city can fine landlords for bed bugs, and the state is considering a bill that requires the notification of parents when an infestation occurs at school. |

|

DUTCH ELM Ophiostoma novo-ulmi Native home: Asia How it got here: Came on imported timber in 1928. Threat: A fungus-caused and beetle-borne disease that can kill entire elm trees. It can also spread from one tree’s roots to another’s if two trees are close together. Government action: Thirty-five elms in Central Park have been infected, and 21 eradicated. The Central Park Conservancy has spent over $150,000 handling the problem, the site says. Containing the disease involves injecting fungicide in tree trunks, pruning affected branches and removing trees that are beyond salvation. |

|

ASIAN LONGHORN BEETLE Anoplophora glabripennis Native home: China How it got here: Believed to have come via shipping crates. Threat: The beetle, which was first found in the city in Greenpoint in 1996, can kill large swaths of hardwood, deciduous trees after laying eggs in their bark. They have been found in every borough, except the Bronx, and commonly attack maple, horsechestnut, elm, willow, birch, poplar, and ash trees. Government action: The city has established quarantined zones where infested trees are removed and chipped. These trees cannot be picked up with the rest of a resident's trash. |

|

NORTHERN SNAKEHEAD FISH Channa argus Also known as: Frankenfish Native home: China How it got here: unclear, but first discovered in Maryland, May 2002 Threat: According to a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service news release, snakeheads are “voracious eating machines” that can ravage the natural balance of any freshwater environment. Government Action: The federal government banned snakeheads and their eggs in 2002. In New York, recent infestations have taken over the river system in Orange County’s Ridgebury Lake area. Residents are working with the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation to flush the river with Rotenone, a low-toxic pesticide, and clear the river of all fish in an effort to stop the snakehead’s proliferation. |

Back to Invasion New York