Under a new name, census data stands ready for perusal

The 2010 census has been rolling out since February with New York state getting the first of its data on March 24 and more data releases during the summer. Yet, almost every day reporters, redistricting specialists and even other demographers ask when data to answer questions such as the following will be released:

- When will we know the number of immigrants in New York City and in various neighborhoods throughout the city?

- How many Hispanic citizens of voting age live in Washington Heights?

- Has the median income in Jackson Heights grown or declined since 2000?

- How many veterans from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars live in Staten Island? In the Bronx? On the Upper West Side?

- Which recent college graduates are ending up with jobs? How much do they make? How many are living at home with their parents?

- Has the number of people working in finance increased?

The answer is simple and surprising: "All the information you need was already released on Dec. 14 last year."

As you may recall, the census form you filled out last spring had just a few basic questions. So the data released on the basis of that can only include: number of people, dwelling owned with or without a mortgage or rented with or without cash rent, relationship to householder, sex, age, and race or races, including principal tribe or group, if Native-American, Asian or Pacific Islander. The other data -- indeed the data that in many ways is the most interesting and heavily used -- comes from the American Community Survey, or ACS, which is actually "the rest of the census" and was released in December.

The New Census

The census has been radically redesigned, and many census users have yet to catch up. Every census from 1940 through 2000 included a "short form" given to everyone to get a full enumeration of the population, as dictated by law. It asked only for very basic demographic information. The Census Bureau also administered a "long form" questionnaire that went to only a sample of persons or households and included a much larger set of social and demographic questions.

In 2000 the short form included only eight questions for the householder and six for every person living in the household. These were the same basic questions that would be asked in 2010 about sex, age, relationship to the householder, race and Hispanic status.

About one in six households received the "long form," which included some 53 questions. In addition to the basic questions in every census form, this survey also contained questions on a whole panoply of characteristics, including housing, moving in the last five years, employment, detailed income sources, military service, disability status, ancestry, place of birth and education.

Until 2010, the long form and short form were distributed in tandem, but then the government split them. Beginning in 2005, the Census Bureau began to collect data for the American Community Survey, which is very similar to the old long form. That survey gets responses from about 2 million households and residents of group quarters (prison, dormitory, institution) every year, and tracks the same sort of data that was produced by the long form sample. The survey takes place all year and interviews, where necessary, are conducted by permanent staff -- not the temporary workers who interview for decennial census.

The Census Bureau releases three sets of data each year from the community survey: the one-year, the three-year and the five-year files. The one-year file is released for areas of at least 65,000 in population, the three-year file for areas of at least 20,000 and the five-year file for all of the areas for which the long form was released (block-groups, tracts and higher). The census releases data only for certain locations with larger populations at one and three-year intervals. This is because, since the ACS is a sample, its reliability depends on sample size.

So on Dec. 14, 2010, the Census Bureau released the first five-year file from the American Community Survey, including all the data that used to be released from the census long form. This totaled 32,000 columns with 675,000 rows of data. These data are comparable to what was compiled from the 2000 Census and allow one to answer many questions at the neighborhood level, where data are needed beyond the few questions in the 2010 census.

Using the Data

There are some differences between the American Community Survey and the old census long form. The first five-year file includes data from 2005 through 2009, while the long form data were collected on the same date as the census. So now relatively current data are available and updated every year. This can be problematic for users -- for instance, the five-year file includes data from both before and after the financial crisis of 2007-08. On the other hand, the benefit is that even for small areas data never are more than a few years out of date. For larger areas the one-year file (from 2009) and the three-file (for 2007-2009) also are available. So we now have detailed social and economic data for a large sample available in a much more timely fashion every year.

As was the case with the long form, the community survey is a sample and so subject to sampling error. The confidence interval is often expressed as percent or number plus or minus another number that defines the interval. For instance: Bush 51, Gore 49 plus or minus 3 percent. The estimate should be between 54 percent Bush, 46 percent Gore to 48 percent Bush to 52 percent Gore. This would be accurate 90 percent, 95 percent or 99 percent of the time, depending upon the level chosen.

Unfortunately, the Census Bureau's approach to estimating the confidence interval is flawed in a number of ways and vastly overestimates the potential error in many instances. For example, if no one is found from a given group, say Native Americans or Italians or Colombians in a given tract in Brooklyn, the confidence interval is arbitrarily set to some number (often 75) and is noted in the data. This would mean, if it were taken literally, that the number of a group in a given tract could be plus or minus 75 and potentially create a negative population count. The Census Bureau now has a note that such absurdities should not be taken seriously, but this implies that the method for computing confidence intervals they used is wrong.

The bureau also used this flawed method in deciding whether to release tables for specific areas from the one-year and three-year files, something it calls "filtering." For example, for years, the bureau did not release foreign place of birth for people living in the Bronx or Staten Island. There are many, many examples of filtered data, which makes the data less useful. (A memo I wrote to the Census Bureau on the topic of their estimation of confidence intervals and it misuse, along with the agency's response is available here. )

At this point, the Census Bureau is mulling over what to do, but in the meantime one should realize that many of the reported confidence intervals are too large and can make it difficult to correctly estimate the confidence interval in cases where the user wants to combine data from individual neighborhoods to come up with statistics for larger areas.

A second issue with the American Community Survey is that its results at the county level are forced to conform to the system used by Census Bureau for yearly population estimates. This means that the actual number reported for a given location in the community survey may conflict with the census counts. This problem, of course, afflicts New York City, where the American Community Survey and census estimates are much higher -- about 250,000 people -- than the census counts. However, the proportions of a given group or category in the community survey should be correct, even if the totals are incorrect. Direct comparisons of totals in the survey files with those in the census files, though, can lead to anomalies.

In sum, despite some differences between the American Community Survey and the old census long form data, the survey is in most ways superior. Not only is the data released more often and in a more timely fashion, but the numbers may be more accurate since the survey is conducted by a permanent interview staff. So the next time you cannot find the data you want in the census report look for it in the American Community Survey.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Under a New Name, Census Data Stands Ready for Perusal

The 2010 census has been rolling out since February with New York state getting the first of its data on March 24 and more data releases during the summer. Yet, almost every day reporters, redistricting specialists and even other demographers ask when data to answer questions such as the following will be released:

- When will we know the number of immigrants in New York City and in various neighborhoods throughout the city?

- How many Hispanic citizens of voting age live in Washington Heights?

- Has the median income in Jackson Heights grown or declined since 2000?

- How many veterans from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars live in Staten Island? In the Bronx? On the Upper West Side?

- Which recent college graduates are ending up with jobs? How much do they make? How many are living at home with their parents?

- Has the number of people working in finance increased?

The answer is simple and surprising: "All the information you need was already released on Dec. 14 last year."

As you may recall, the census form you filled out last spring had just a few basic questions. So the data released on the basis of that can only include: number of people, dwelling owned with or without a mortgage or rented with or without cash rent, relationship to householder, sex, age, and race or races, including principal tribe or group, if Native-American, Asian or Pacific Islander. The other data -- indeed the data that in many ways is the most interesting and heavily used -- comes from the American Community Survey, or ACS, which is actually "the rest of the census" and was released in December.

The New Census

The census has been radically redesigned, and many census users have yet to catch up. Every census from 1940 through 2000 included a "short form" given to everyone to get a full enumeration of the population, as dictated by law. It asked only for very basic demographic information. The Census Bureau also administered a "long form" questionnaire that went to only a sample of persons or households and included a much larger set of social and demographic questions.

In 2000 the short form included only eight questions for the householder and six for every person living in the household. These were the same basic questions that would be asked in 2010 about sex, age, relationship to the householder, race and Hispanic status.

About one in six households received the "long form," which included some 53 questions. In addition to the basic questions in every census form, this survey also contained questions on a whole panoply of characteristics, including housing, moving in the last five years, employment, detailed income sources, military service, disability status, ancestry, place of birth and education.

Until 2010, the long form and short form were distributed in tandem, but then the government split them. Beginning in 2005, the Census Bureau began to collect data for the American Community Survey, which is very similar to the old long form. That survey gets responses from about 2 million households and residents of group quarters (prison, dormitory, institution) every year, and tracks the same sort of data that was produced by the long form sample. The survey takes place all year and interviews, where necessary, are conducted by permanent staff -- not the temporary workers who interview for decennial census.

The Census Bureau releases three sets of data each year from the community survey: the one-year, the three-year and the five-year files. The one-year file is released for areas of at least 65,000 in population, the three-year file for areas of at least 20,000 and the five-year file for all of the areas for which the long form was released (block-groups, tracts and higher). The census releases data only for certain locations with larger populations at one and three-year intervals. This is because, since the ACS is a sample, its reliability depends on sample size.

So on Dec. 14, 2010, the Census Bureau released the first five-year file from the American Community Survey, including all the data that used to be released from the census long form. This totaled 32,000 columns with 675,000 rows of data. These data are comparable to what was compiled from the 2000 Census and allow one to answer many questions at the neighborhood level, where data are needed beyond the few questions in the 2010 census.

Using the Data

There are some differences between the American Community Survey and the old census long form. The first five-year file includes data from 2005 through 2009, while the long form data were collected on the same date as the census. So now relatively current data are available and updated every year. This can be problematic for users -- for instance, the five-year file includes data from both before and after the financial crisis of 2007-08. On the other hand, the benefit is that even for small areas data never are more than a few years out of date. For larger areas the one-year file (from 2009) and the three-file (for 2007-2009) also are available. So we now have detailed social and economic data for a large sample available in a much more timely fashion every year.

As was the case with the long form, the community survey is a sample and so subject to sampling error. The confidence interval is often expressed as percent or number plus or minus another number that defines the interval. For instance: Bush 51, Gore 49 plus or minus 3 percent. The estimate should be between 54 percent Bush, 46 percent Gore to 48 percent Bush to 52 percent Gore. This would be accurate 90 percent, 95 percent or 99 percent of the time, depending upon the level chosen.

Unfortunately, the Census Bureau's approach to estimating the confidence interval is flawed in a number of ways and vastly overestimates the potential error in many instances. For example, if no one is found from a given group, say Native Americans or Italians or Colombians in a given tract in Brooklyn, the confidence interval is arbitrarily set to some number (often 75) and is noted in the data. This would mean, if it were taken literally, that the number of a group in a given tract could be plus or minus 75 and potentially create a negative population count. The Census Bureau now has a note that such absurdities should not be taken seriously, but this implies that the method for computing confidence intervals they used is wrong.

The bureau also used this flawed method in deciding whether to release tables for specific areas from the one-year and three-year files, something it calls "filtering." For example, for years, the bureau did not release foreign place of birth for people living in the Bronx or Staten Island. There are many, many examples of filtered data, which makes the data less useful. (A memo I wrote to the Census Bureau on the topic of their estimation of confidence intervals and it misuse, along with the agency's response is available here. )

At this point, the Census Bureau is mulling over what to do, but in the meantime one should realize that many of the reported confidence intervals are too large and can make it difficult to correctly estimate the confidence interval in cases where the user wants to combine data from individual neighborhoods to come up with statistics for larger areas.

A second issue with the American Community Survey is that its results at the county level are forced to conform to the system used by Census Bureau for yearly population estimates. This means that the actual number reported for a given location in the community survey may conflict with the census counts. This problem, of course, afflicts New York City, where the American Community Survey and census estimates are much higher -- about 250,000 people -- than the census counts. However, the proportions of a given group or category in the community survey should be correct, even if the totals are incorrect. Direct comparisons of totals in the survey files with those in the census files, though, can lead to anomalies.

In sum, despite some differences between the American Community Survey and the old census long form data, the survey is in most ways superior. Not only is the data released more often and in a more timely fashion, but the numbers may be more accurate since the survey is conducted by a permanent interview staff. So the next time you cannot find the data you want in the census report look for it in the American Community Survey.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Failure of Redistricting Reform Could Bring Reprise of 2002's Fiasco

As the current state legislative session winds down, efforts to reform the redistricting process in New York state appear to be dead. Yet, at this very moment the new Citizens Redistricting Commission in California, which has final authority, has released a preliminary plan that in the process of cleaning up lines would radically alter the California congressional delegation.

It would add up to five Hispanic seats, increase the number of Democrats and throw a number of sitting U.S. representatives into the same district. Beyond that, the commission's proposal may end up creating the Democratic super majorities in both houses of the state legislature needed to raise the state's taxes and pull it out of its financial crisis.

Meanwhile in New York state, despite former Mayor Ed Koch's efforts to get many legislators to pledge to vote for reform, despite the fact that Gov. Andrew Cuomo claims to be making it a priority and despite universal support of the usual good government groups, no bill has been reported out or is expected to come to the floor before the session is over in a few days. This means that the same chaotic system that brought us an impasse in Congress and the deadlocked State Senate will remain in place for this round.

Obstacles n New York

The California experience throws into high relief why reform of the legislature by the legislature repeatedly fails in New York state despite receiving lip service support for the last few years. Two reasons stand:

- If the system changed, incumbents would not be protected, and many would face opponents who are also sitting legislators.

- Under the current system, demographic shifts that would throw both houses into Democratic hands can be contained. This was done in 2002 and will likely be repeated this time around.

A constitutional amendment would make it possible to have the type of reform that happened in California. But for that to happen, the legislature would have to pas the measure in two sessions, and the voters would then have to ratify it.

The Democrats could have started the process by passing a constitutional amendment on redistricting reform last year when they controlled both houses of the legislature. They did not. If they had -- and if the amendment passed again this term -- it could have been on the ballot this November, in time for this round of redistricting.

The enactment of a legislative reform remains possible. This would mean that a commission would draw lines, but the legislature and the governor would have to approve the lines and so would have final say. Even this limited reform has not made it to the floor of either house.

When one looks at what is ahead for redistricting, it is obvious why this has happened. Republican senators do not want to lose their majority, and the Democrats in the Assembly do not want to risk their individual seats and lose a few members from the majority, despite their overwhelming advantage. This stalemate occurred even though the fiasco that was redistricting last time is about to be rerun, and everyone claims to support reform.

The Results Last Time

The population shifts found in the 2010 census are very similar to those in 2000, and now as then two congressional seats have been lost. In 2002 a judge declared an impasse after the legislature failed to act, and a set of congressional lines were proposed by a special master. At the point a deal was cut and the present congressional lines were approved.

In the last redistricting, all plans initially considered for the State Senate involved 61 seats, the total number at that time. Then at the 11th hour, a new plan was proposed. It added one seat downstate bringing the total number of senate districts to 62.

In addition, the plan carefully allocated the population so that every district downstate was overpopulated and every district upstate was under populated. It also maintained the so-called Velella racial gerrymander, (the seat now held by Jeffrey Klein); and cracked and packed minorities in Long Island. "Cracking" involves splitting a large bloc of minority voters into several districts, so that they cannot chose their preferred candidate. "Packing" means putting a large block of minorities into one district so as to reduce their impact several districts.

This plan was challenged in federal court unsuccessfully. Because it allowed for an even number of senators, it led directly to the State Senate deadlock in 2009.

The Assembly plan in some ways was the mirror image of the Senate plan. Most districts upstate were over populated, many downstate were under populated. Incumbents were protected.

What Can We Expect This Time?

I have prepared data on the population and the citizens of voting age population by various groups for the present set of lines. Here is what New York State faces. For Congress:

- All congressional districts are under populated. (Congressional seats are required to be effectively equal.)

- Two seats will be lost, One from districts from 1 to 14 or 15, which encompasses the city and its suburbs. The other seat will come from upstate -- from districts 16 through 29.

- Districts 10, 6 and 11have a majority of voting age citizens who are African Americans.

- District 16has a majority of Hispanic voting age citizens.

- Two additional districts have a majority of Hispanic and African Americans of voting age combined. Two more are near such a majority.

For the State Senate:

- 13 districts are under populated (based upon a deviation of 5 percent from the ideal), while eight are over populated.

- Most under-populated districts are upstate.

- Six districts have a majority of African American citizens of voting age.

- Two districts have a majority of Hispanic citizens of voting age.

- Four districts have a majority of Hispanics and African Americans of citizen of voting age combined.

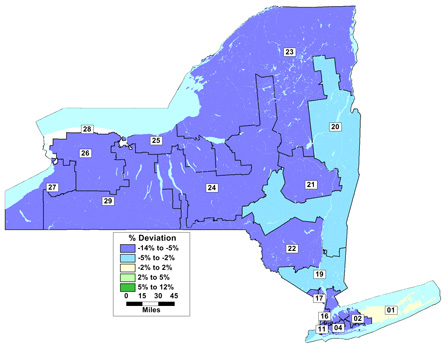

Under New York's current State Senate districts, voters upstate -- many in largely Republican areas -- have more clout than their downstate counterparts. Most of the districts with fewer voters than average are upstate, while those with a larger number of voters are more likely to be closer to New York City. For a map showing how much each State Senate district deviates from the average -- or ideal -- size, go here.

Under New York's current State Senate districts, voters upstate -- many in largely Republican areas -- have more clout than their downstate counterparts. Most of the districts with fewer voters than average are upstate, while those with a larger number of voters are more likely to be closer to New York City. For a map showing how much each State Senate district deviates from the average -- or ideal -- size, go here.

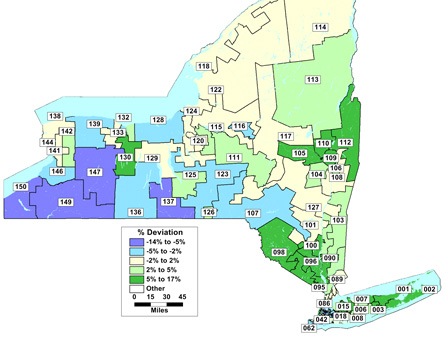

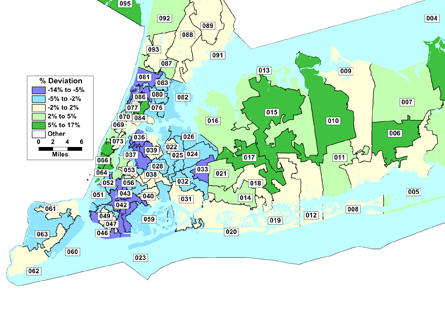

Many of the State Senate districts in and around the city are larger than normal for the state, giving their residents less power. A glaring exception is District 31, stretching along the West Side of Manhattan and into the Bronx. For a map showing how much each district in the metropolitan area deviates from the average -- or ideal -- size, go here.

Many of the State Senate districts in and around the city are larger than normal for the state, giving their residents less power. A glaring exception is District 31, stretching along the West Side of Manhattan and into the Bronx. For a map showing how much each district in the metropolitan area deviates from the average -- or ideal -- size, go here.For the Assembly:

- 26 districts are under populated and 22 are over populated based upon a 5 percent deviation.

- Fifteen districts have a majority of Africans American citizens of voting age.

- Twelve districts have a majority of Hispanic citizens of voting age.

- Eight additional districts have a majority of Hispanics and African American citizens of voting age combined.

For a table listing all 150 State Assembly districts and their demographic characteristics, as well as their size, go here.

Hammer Lock

The population's changes are massive, but the legislature together with the governor have chosen to keep complete control of the redistricting process (except for possible court or Justice Department intervention) for another round. They will maintain their power, as they have in the past. Unlike California, there is little prospect for fair redistricting in New York State, only chaos similar to the last round. (To view my recent testimony in Albany on Redistricting Reform, go here and here.)

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.