Census Wounded City's Pride but Probably Got the Numbers Right

The 2010 census poured cold water on Mayor Michael Bloomberg's rosy view that New York City would hit 9 million long before 2030. The census found that, instead of growing to 8,421,789 residents as the census estimated just a few days before the official numbers were released, New York City had only 8,175,153 residents, some 246,636 less than expected.

The estimated brisk growth pace of 5.2 percent since 2000, suddenly became a phlegmatic 2.1 percent. Indeed, if present trends continue New York City will not make it to 9 million until sometime in the decade of 2050. In short, the growth rate, if correct, means that many of the enthusiastic proclamations about the city's unique growth and its attractiveness as a place to live are simply wrong.

Predictably, the mayor, who made his fortune purveying presumably accurate financial information, is not willing to believe that the census's careful enumeration of New York’s population could be correct. He is planning to challenge it, and other officials are supporting that challenge. However, instead of taking the issue to court, they plan to invoke the Census Bureau's own Count Resolution process. This is a technical procedure that generally corrects blatantly wrong counts. After 2000, for example, the Census Bureau placed a number of prisons and college dorms in the wrong cities, counties and towns. When these mistakes were brought to the Census Bureau’s attention, it corrected such obvious errors.

New York's argument for an adjustment is much more complex relying as it does upon the increase in vacancies and the undercounting of immigrants. Indeed, there are at least four reasons to have confidence in the census count.

1. Housing vacancies are on the rise in New York City and throughout the country:

Over the decade New York City did see an increase of about 170,000 housing units, but, according to the Census, the number of vacant units rose by some 82,000.

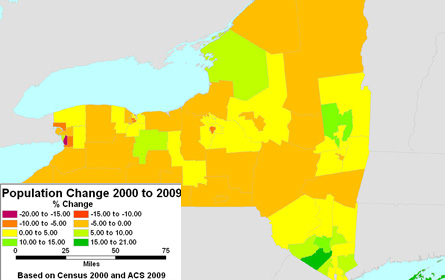

Bloomberg explanation: The census misclassified many occupied units as vacant.

Possible other explanation: Many of the new units were built as part of the boom and remain vacant. As the accompanying map shows, the rise in vacant units occurred not in the immigrant areas in Brooklyn and Queens, but rather in other areas such as the far West Side and Bay Ridge Brooklyn. Most of the other cities in the United States experienced a large increase in the proportion of vacant units. Indeed New York City's increase of 2.15 percent means that it ranked 79th out of the 109 cities with more than 200,000 population in 2010. New York City, along with the rest of the United States, experienced a housing bubble and still working through the extra units that were constructed during that bubble. So the vacancies may be real, unless New York City experienced growth unlike any city in the country.

2. This census missed many immigrants.

The Bloomberg administration has said the census staff was unable to count many newcomers to the city, particularly those who came to the country illegally or live in illegally divided apartments.

Other explanation: Of course some immigrants were missed, but it is also true that immigration of all sorts slowed during the financial crisis. It may be that New York’s immigrant fueled growth may have tapered off.

Certainly the strong increase in immigrants seen in places like Queens and Brooklyn during the decade of the 1990s has slowed substantially, as the climate for immigrants has become much less friendly nationally and their job prospects have ebbed. Indeed, Jeffrey Passel and D'Vera Cohn at the Pew Center estimatedthat the number of illegal immigrants to the US declined by about one million between 2007 and 2009. New York City seems likely to have experienced some of this decrease.

3. The 2000 census may have overcounted New York City.

This is a seldom discussed point, but if the census, because of the very real difficulties of getting an accurate count in a city as diverse as new York, could have overcounted the number of people in the five borough in 2000 due to putting phantom residents into housing units that did not exist or by double counting some. (For more on this, see my earlier column.) If this happened and the excess was reversed in 2010, New York City's apparent growth would be less than its real growth.

Apparently the census also considered this possibility as I outline in another previous column: . If the city had been overcounted by say 200,000 in 2000, and was not overcounted this time, its real growth would actually be about 4.7 percent. Any overcount would serve as the base for the census estimates during the past decade, so if the city were overcounted by 200,000 in 2000 -- and so really had about about 7.8 million people -- then the estimated growth of roughly 420,000, would bring the census estimate almost exactly to the same number as were counted in 2010.

4. The 1990 census undercounted New York's population.

An undercount in the 1990 census, which New York and other big cities challenged in an unsuccessful lawsuit, means that the increase in the 1990s was overstated. Any undercount in 1990 combined with the possible overcount in 2000 would have inflated the percentage growth between 1990 and 2000. Because many demographic and econometric models use recent growth to estimate future growth, the projection for the first decade of the 21st century then could have vastly overestimated population growth.

All in all then, it is quite likely that the 2010 census count is basically accurate, but that the growth rate for the city is more than suggested by the change between 2000 and the 2010 census. New York, it seems, did participate in the slowing of immigration and overbuilding that were common in the 2000s.

When question about the city's growth, Bureau of the Census director Robert Groves said, "This is the time when many mayors receive counts that disappoint." Though Bloomberg and his administration indeed may be disappointed, the census surprise for New York City pales in comparison with that for Detroit. The wrong estimate there implied that Detroit had about 200,000 more people than it had -- meaning the numbers originally projected the Motor City as being 28 percent larger than it turned out to be.

Many cities in the United States, especially in the East, had population loss or very slow growth since 2000. Maybe it is disheartening that New York’s apparent growth in the 1990s did not continue into the 2000s, but after the 9/11 attacks and the financial crisis, maybe the city's continued though slower growth indicates not weakness but just how robust New York City is.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Census Brings Unpleasant Surprise for State Politicians

New York state received a nasty surprise from the Census Bureau on Dec. 21. According to the first results from census 2010, the state has 163,351 fewer people than the bureau estimated it did on July 1, 2009. As a result, New York will lose two congressional seats, bringing its total down to 27, tying it with Florida.

The loss of two congressional seats will set off a huge redistricting fight. Beyond representation in Congress, the diminished New York state population will have a major impact on the amount of federal aid that the state receives.

The Missing New Yorkers

If New York's population had matched the July 1, 2009 estimate, it would have lost only one seat. If the estimated rate of growth in the population from 2008 to 2009 had continued to April 1, 2010, then the state would have 19,596,910 residents, some 218,808 more than the 19,378,102 persons who were actually enumerated.

Demographers and politicos are scratching their heads trying to figure out how this happened and what the implications will be. Unlike California, which has already claimed an undercount and protests the census results , New York state is still contemplating the impact and sources of this apparent population loss.

An examination into which parts of the state were overestimated or undercounted is necessary. Once the redistricting data are released in March, we will have much better information.

In general, though, there are three possible explanations:

-- The procedure by which the census creates estimates is flawed.

-- There are problems with the census 2010 count.

-- The 2000 count may have been somewhat inflated, and the new count reflects a return to reality.

Each of these explanations could be true in various ways. The census estimates are based upon births and deaths and international and domestic migration. Immigration -- foreign or domestic -- is particularly hard to capture, and the number of immigrants to New York state may have declined. Foreign immigration would mostly affect the city and downstate, while domestic immigration is important upstate.

New York state has many "hard to count" areas, especially in the city. Though major efforts were made to count residents from these areas, it may be that the backlash from 9/11 and a perceived increase in anti-immigration sentiment led some immigrants to be less willing to participate in the census than they were in 2000. Similar problems may have affected upstate, if the census outreach was ineffective.

Finally, technical issues related to the addition of extra addresses arising from a census check of addresses in 2000 may have led to duplication. If so, it is possible that the city population was somewhat overcounted in 2000. Since the census numbers from 2000 become the base for the census estimates, if those extra addresses were removed or the Census Bureau eliminated more duplicate addresses, then the population in the city, especially in parts of Queens and Brooklyn would be less than was estimated.

Up for Grabs

Whatever the reason for the lower count in New York State, the implications for congressional redistricting are massive. Most of the population losses occurred in upstate New York, while the gains were in areas in and around the city, most particularly in outer ring suburbs.

The table below shows each district's population gain or loss, and some characteristics of the district, including the current incumbent, his or her party, the member's vote in the November elections and the degree to which the districts deviates from the ideal population size of 717,707 people.

| District | Party | Name | Incumbent | 2010 Vote Percentage | Pop 2000 | Estimated Population 2010 | Change from 2000 | Deviation from Ideal | % Deviation |

| 1 | Dem | Timothy Bishop | Yes | 50.05 | 654,360 | 713,122 | 58,762 | -4,586 | -0.64% |

| 2 | Dem | Steve Israel | Yes | 56.60 | 654,360 | 687,889 | 33,529 | -29,819 | -4.15% |

| 3 | Rep | Peter King | Yes | 72.00 | 654,361 | 653,477 | -884 | -64,230 | -8.95% |

| 4 | Dem | Carolyn McCarthy | Yes | 53.70 | 654,360 | 657,810 | 3,450 | -59,897 | -8.35% |

| 5 | Dem | Gary Ackerman | Yes | 62.40 | 654,361 | 699,143 | 44,782 | -18,565 | -2.59% |

| 6 | Dem | Gregory Meeks | Yes | 94.90 | 654,361 | 654,564 | 203 | -63,144 | -8.80% |

| 7 | Dem | Joseph Crowley | Yes | 79.70 | 654,360 | 673,522 | 19,162 | -44,186 | -6.16% |

| 8 | Dem | Jerrold Nadler | Yes | 75.00 | 654,360 | 695,491 | 41,131 | -22,217 | -3.10% |

| 9 | Dem | Anthony Weiner | Yes | 58.50 | 654,360 | 691,231 | 36,871 | -26,476 | -3.69% |

| 10 | Dem | Edolphus Towns | Yes | 91.00 | 654,361 | 680,793 | 26,432 | -36,915 | -5.14% |

| 11 | Dem | Yvette Clarke | Yes | 90.30 | 654,361 | 668,394 | 14,033 | -49,314 | -6.87% |

| 12 | Dem | Nydia Velazquez | Yes | 92.90 | 654,360 | 688,434 | 34,074 | -29,273 | -4.08% |

| 13 | Rep | Mike Grimm | No | 51.50 | 654,361 | 698,637 | 44,276 | -19,071 | -2.66% |

| 14 | Dem | Carolyn Maloney | Yes | 74.90 | 654,361 | 666,335 | 11,974 | -51,372 | -7.16% |

| 15 | Dem | Charles Rangel | Yes | 79.90 | 654,361 | 661,747 | 7,386 | -55,961 | -7.80% |

| 16 | Dem | Jose E. Serrano | Yes | 95.40 | 654,360 | 684,421 | 30,061 | -33,287 | -4.64% |

| 17 | Dem | Eliot Engel | Yes | 72.10 | 654,360 | 668,910 | 14,550 | -48,797 | -6.80% |

| 18 | Dem | Nita Lowey | Yes | 62.00 | 654,360 | 669,824 | 15,464 | -47,883 | -6.67% |

| 19 | Rep | Nan Hayworth | No | 52.80 | 654,361 | 709,848 | 55,487 | -7,859 | -1.10% |

| 20 | Rep | Christopher Gibson | No | 55.40 | 654,360 | 675,617 | 21,257 | -42,091 | -5.86% |

| 21 | Dem | Paul Tonko | Yes | 59.30 | 654,361 | 660,109 | 5,748 | -57,599 | -8.03% |

| 22 | Dem | Maurice Hinchey | Yes | 52.40 | 654,361 | 662,365 | 8,004 | -55,342 | -7.71% |

| 23 | Dem | Bill Owens | Yes | 48.10 | 654,361 | 652,743 | -1,618 | -64,965 | -9.05% |

| 24 | Rep | Richard Hanna | No | 52.90 | 654,361 | 633,497 | -20,864 | -84,210 | -11.73% |

| 25 | Rep | Ann Marie Buerkle | No | 50.20 | 654,361 | 646,863 | -7,498 | -70,845 | -9.87% |

| 26 | Rep | Christopher Lee | Yes | 73.80 | 654,361 | 646,879 | -7,482 | -70,829 | -9.87% |

| 27 | Dem | Brian Higgins | Yes | 60.80 | 654,361 | 624,284 | -30,077 | -93,423 | -13.02% |

| 28 | Dem | Louise Slaughter | Yes | 65.20 | 654,360 | 604,913 | -49,447 | -112,795 | -15.72% |

| 29 | Rep | Thomas Reed | No | 56.50 | 654,361 | 647,243 | -7,118 | -70,465 | -9.82% |

As the table makes plain, Districts 1 through 19 will need to lose one seat, while districts 20 through 29 will lose the second seat. Though District 28, represented by Louise Slaughter, and District 27, represented by Brian Higgins, are the farthest below the new ideal of 717,707, it will require 10 districts becoming only 9 to make upstate districts conform to population equality. Similarly, even though most districts in the downstate area have been growing, the 19 downstate districts will need to become 18 to leave New York with the 27 seats to which it is entitled.

Thanks to the new census count, New York state is now in for two separate games of musical chairs to find out which representatives will no longer have seats to call their own.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Census Likely to Offer Accurate Count of New Yorkers

The 2010 census appears to be on its way to be a major success for New York City. We should be grateful for the unprecedented engagement of community, neighborhood and ethnic organizations, as well as adequate funds for communication, outreach and advertising. This all led to a substantial increase in the rate of initial mail response for New Yorkers. When the state population counts that determine the number of seats in Congress are released on Dec. 28t and the block level data for reapportionment for legislative districts are released in March, New York City should do quite well.

The initial response rate rose from 57 percent in 2000 to 60 percent in 2010 in New York City. The overall national rate stayed the same at 72 percent.

The increased initial participation in the city means both better data and cheaper data collection. When people respond to the initial mailing, the Census Bureau does not have send out enumerators to knock on doors and collect the information, saving money.

While some households that do not respond become "hard to count," the largest fraction of households visited by enumerators easily provided information when contacted, some even apologizing for not sending in their form on time. Other housing units whose residents did not respond proved to be vacant. Enumerators revisited any vacant units to confirm that no one lived there.

Filling in the Gaps

Of course, in any huge operation like the census there are bound to be glitches here and there, but the Census Bureau established built in checks to assure accuracy. Most of the error and difficulties encountered by some census enumerators will be corrected during the quality control phase. For instance, any home that had an incorrect address was rechecked, and a small sample of households is being reinterviewed to validate the accuracy of the original count. Checks also exist to eliminate duplicate responses for those who filled out the form in more than one residence.

Despite the relative success and the efforts at quality control, some groups are very difficult to interview, leaving some missed homes and some incorrect or inconsistent information. To address this, the Census Bureau has a number of procedures it follows when it cannot get an interview or the response is either not complete or inconsistent with other responses from the household. These technique, based on statistical methods, come under the heading "imputation and allocation. "

There are two types of imputation and allocation:

Whole unit imputation comes into play when there is no answer for a unit known to be occupied. In such cases, the census applies what is known as the "hot deck" procedure and determines -- or imputes -- the characteristics of the household from those of other nearby households.

The term "hot deck" harkens back to the time when computers used punched cards. The hot deck contained information on those who were recently tabulated from the same neighborhood living in the same type of unit. Such data still exists -- even if the hot deck does not -- and is used to fill in information on nearby, missing with similar known characteristics.

The other method is "item and person allocation," where a household has provided answers, but they either incomplete answers or include inconsistencies. Here the information on the occupants that do exist is used to impute, much as the "hot deck'" was for the vacant unit So one can impute sex by using first name, if it is known. A Committee of the National Academy of Sciences discussed and reviewed these census procedures.

The New York Data

In the past, New York City has relied more on imputed data than the U.S. as whole has. The table below presents information on the imputation of basic characteristics in the city in 2000. The census reported that 4.7 percent of the housing units' vacancy statuses were imputed. In 8.9 percent, it imputed whether or not the unit was owned or rented. This compares with 2.6 percent for vacancy and 4.8 percent for owned or rented nationally.

| United States | New York City | Bronx | Kings | Manhattan | Queens | Staten Island | |

| Overall Person Imputations | |||||||

| Any Item Imputed | 10.9% | 20.0% | 26.4% | 22.3% | 16.5% | 17.8% | 10.6% |

| Population Substituted | 1.2% | 3.9% | 5.7% | 5.4% | 1.2% | 3.4% | 1.5% |

| Specific Imputations | |||||||

| One or more items Impurted | 9.6% | 16.1% | 20.7% | 16.9% | 15.2% | 14.3% | 9.1% |

| Race Impurted | 4.0% | 7.4% | 12.3% | 6.9% | 7.1% | 5.9% | 3.7% |

| Hispanic Impurted | 4.4% | 6.5% | 6.8% | 7.5% | 5.6% | 6.2% | 4.1% |

| Sex Impurted | 1.1% | 1.8% | 2.0% | 2.2% | 1.3% | 1.7% | 0.9% |

| Age Impurted | 3.7% | 5.8% | 5.9% | 6.7% | 5.7% | 5.3% | 3.5% |

| Relationship Impurted | 2.1% | 3.6% | 3.9% | 4.2% | 2.8% | 3.5% | 2.0% |

| Housing Imputations | |||||||

| Vacancy Impurted | 2.6% | 4.7% | 5.5% | 4.5% | 4.0% | 5.7% | 3.1% |

| Tenure Impurted | 4.8% | 8.9% | 12.4% | 11.0% | 5.8% | 8.0% | 5.1% |

| Source: Census 2000 Tabulation From Summary File 1. | |||||||

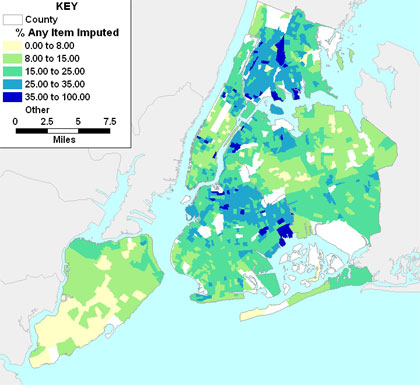

As to imputation for persons, some 20 percent of New York City's 2000 population had at least one item imputed, compared with 10.8 percent for the United States as a while For example, in New York City 11.3 percent of people had their race imputed, versus 5.2 percent for the United States . In the Bronx, the figures are 26.4 percent for any imputation, and 16.0 percent for race..

Imputation varies widely throughout the city, as the table and map show. Areas with high proportions of poor and minority households, such as much of the Bronx, Bedford Stuyvesant, Flatbush and Harlem, as well as heavily immigrant area like Northwest Queens have high levels of imputation. In most of Staten Island and parts of Queens, and of Manhattan levels of imputation are low.

<br/ >

<br/ >

Imputation makes up for many of the problems in data collection, including non-response and inaccurate or misleading information. It improves the quality of the census and the overall results by filling in holes and fixing other problems.

Since 1980, many have argued for statistical adjustment of the Census based upon sampling of the "hard to count" population. The Supreme Court has ruled against adopting this approach. The census has used imputation and allocation since 1960. So in a later ruling the court found that such methods were a legitimate means to improve the count.

What then of the 2010 census? First, it seems to have done even better in New York than the 2000 Census. Like the 2000 census, 2010 will prove to be better than the 1990 census, which missed on the order of 400,000 New Yorkers. Second, the various quality control methods will help assure accurate information. Third, the use of allocation and imputation means that even where there are gaps or inconsistencies in the collected data, the data will be improved, so the census will be even more reliable. In short, the 2010 Census is shaping up to be very accurate and reliable.

You can count on it!

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.