Can Obama's Plan Erase New York's Jobs Deficit?

The package of job creation and stimulus measures proposed by President Barack Obama last week is welcome medicine for an ailing economy. If adopted, the president's plan will boost job growth and help reduce unemployment that has stayed high despite the fact that the Great Recession of 2008-09 was deemed to have come to an end in June 2009. The president's plan is an important step in the right direction, particularly after a summer of political preoccupation with the long-term federal budget deficit, and it is likely the most that can be done given the current makeup of the Congress.

The effects of that crisis are being deeply felt in New York. Twenty-six months into the "recovery," over 600,000, or one in every seven, New York City workers is unemployed, under-employed or has given up looking for work. While there has been improvement in some economic indicators for the city, job growth has been too weak to put a meaningful dent in the continuing unemployment. The city's overall under-employment rate tops 15 percent, for blacks it's 22 percent, for young black men it's 40 percent.

New York's Numbers

The reported decline in the unemployment rate -- which includes only people actively looking for work -- is deceptive. People who would like to work but have given up on finding a job in this labor market are no longer counted as unemployed. If these discouraged workers were counted, New York City's unemployment rate in July 2011 would have been 10.1 percent, about 1.5 percentage points higher than the official 8.7 percent unemployment rate for that month.

These and other indicators of the continuing "unemployment crisis" in the city and state are documented in the latest edition of The State of Working New York. Long-term unemployment, the report finds, is at record levels for the nation and for New York. Half of those unemployed in New York City and elsewhere around the state have been out of work for more than six months, and 29 percent have been jobless for a year or more.

A great deal of political energy has focused on the federal budget deficit, but the deficit that matters most for many New Yorkers is the "jobs deficit." To bring New York state's unemployment rate back to where it was before the recession, New York would need 512,000 additional jobs today.

Hundreds of thousands of New York families are struggling to make ends meet and to keep a roof over their heads. Worker skills are eroding, and the likelihood that tens of thousands of long-term unemployed workers will never productively re-enter the work force increases with every passing month. Our economy is squandering the productive labor of unemployed men and women on a colossal scale, and our homegrown small businesses that depend on local sales are put in jeopardy because the unemployment crisis deprives them -- even more than other businesses --of customers with money in their pockets.

The Weak Recovery

This is the weakest recovery from a recession since the 1930s. Following other recessions since World War II, the real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew an average of 5.4 percent in each of the first two years of the recovery. In the two years of this recovery, annual GDP growth has been less than half the average, only 2.5 percent per year. The housing collapse, consumer demand dampened by unemployment, and state and local government budget cuts all contribute to this record weakness.

New York lost fewer net jobs in the 42-month period from the start of the national recession in December 2007 through July 2011 than 40 other states around the country. This is largely because the housing bubble of 2003-to-2007 bypassed upstate New York and the unprecedented taxpayer bailout of the finance sector saved several of the largest New York-based banks and securities firms from catastrophe.

Partly driven by the profit rebound among Wall Street firms but also by gains in many major sectors, New York state ranked second among all states in both real state GDP growth and total personal income growth in 2010. The Empire State recorded a 5.1 percent real GDP gain, second only to North Dakota, and a 4.1 percent total income gain, second only to New Mexico.

Yet this "good news" has done little to help most New Yorkers. The state has seen its employment rate -- the ratio of those holding a job to all working age people -- continue to decline during the recovery, dropping from 57.3 percent at the end of 2009 to 56.9 percent in the first half of 2011.

New York state has re-gained 118,000 of the 316,000 payroll jobs lost during the recession, or 37 percent. Fourteen of the 18 major sectors of the state's economy lost jobs during the recession, but only two (other services and management of companies) have completely made up recession losses. The two sectors that lost the most jobs -- manufacturing and construction -- continued to lose jobs, but at a much slower pace through June 2011.

In the first half of 2010, New York City had gained jobs faster than the nation, but since then the city's job growth has been about the same as for the nation overall.

Government is the only sector that has lost more jobs during the recovery than during the recession. Over the past three years, New York has lost 54,000 jobs for teachers and other state and local public servants. That is a greater decline than in any other sector except for manufacturing, with government seeing more jobs lost than finance and insurance, or construction. It is expected that New York's schools opened this fall with 12,000 fewer teachers and other staff than they had last spring.

The problems in the city and state reflect those in the nation as a whole. In the last three or four months, job growth and other economic indicators have slowed so much that more and more economists are talking about the risk of a "double dip recession." It is in this context that the president correctly shifted his focus at the end of summer from the federal budget deficit to the national jobs deficit.

The President's Prescription

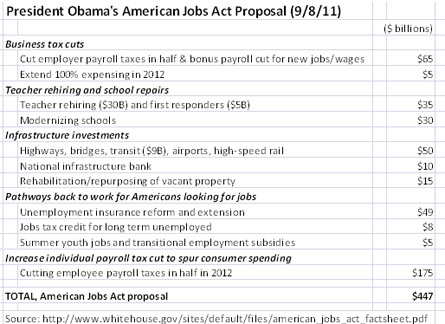

The president's $447 billion American Jobs Act proposal includes a range of measures to increase consumer spending, re-hire public school teachers, expand infrastructure investments, and provide tax cuts to businesses to spur hiring. Some of it continues current programs that expire at the end of this year, like federally funded extended unemployment benefits. Others enhance remedies currently in place like Obama's proposal to up the individual payroll tax cut from 2 percent to 3.2 percent. (See the box below for the main components.)

The proposed American Jobs Act is a little more than half the size of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), the $787 billion stimulus legislation crafted by Obama's presidential transition team and House Democrats and passed by Congress in February 2009, with not a single House Republican voting in favor.

With the House Democrats' loss of their majority in the 2010 midterm elections, the united opposition of the House Republicans is now a real impediment to the making of coherent economic policy. The jobs act, for example, includes far less money than the recovery act to provide relief to state and local government budgets, and proportionately relies far more on tax cuts. The $35 billion proposed in the jobs act for state and local governments to re-hire teachers and first responders will help to reduce the negative impact that state and local job cuts are having on the recovery. The current bill, though, does not include an increase in the federal Medicaid share that was the main form of state fiscal relief in the recovery act.

In another important difference, well over half -- 57 percent -- of the jobs act funding takes the form of tax cuts; in the recovery act, tax cuts accounted for about 37 percent of the total. Even though most economists believe that direct spending provides more economic stimulus bang for the buck than do tax cuts, the president has likely crafted a package heavy on tax cuts to try to win Republican support.

Mark Zandi of Moody's Analytics and an economic advisor to 2008 Republican presidential nominee John McCain, has written that, if enacted, the Obama jobs plan can add 1.9 million jobs and 2 percentage points to GDP growth next year. While Zandi thinks this would keep the economy from sliding back into recession, it would only cut the unemployment rate by one percentage point.

Of course, passage of the act is by no means certain. Zandi and conservative economist Doug Holtz-Eakin believe that key parts of the jobs proposal like the payroll tax cuts, the unemployment insurance extension and some of the infrastructure proposals may garner enough Republican votes to pass. There is also the possibility that conservative interests will refuse to support any meaningful part of the jobs act based on a cynical political perspective that their electoral success in 2012 depends on keeping unemployment high.

What New York Can Do

New York cannot escape the adverse effects of the extremely weak national economy. Whether or not the major elements of the American Jobs Act are enacted, New York policy-makers can do several things to boost jobs and the state's economic future:

- Restore the commitment to having one of the nation’s best educational systems from public schools where all the state's children can receive a sound basic education through a high-quality and affordable public higher education system;

- Revamp regional economic development to put the priority on creating good jobs and to make decisions on subsidies to businesses more transparent and accountable as well as consistent with a coherent regionally based economic strategy;

- Provide technology assistance to advanced manufacturing across the state to support good-paying, high-skilled jobs and foster innovation; and

- Adequately fund transportation infrastructure needs, and exploit the potential of the nation’s largest mass transportation network to promote advanced transit-related manufacturing. (A conference promoting the idea of expanded transit-related manufacturing in New York will be held at the Brooklyn Navy Yard on Sept. 27.)

If New York cuts state income taxes on the wealthiest by $5 billion in 2012 as it is set to do, it will have to make budget cuts that will further damage the precarious recovery and exacerbate the unemployment crisis. Keeping New York's current income-tax surcharge on high-end taxpayers after it is set to lapse in 2012 would make a huge difference in staving off job cuts for state and local government employees, including school teachers and educational support staff. Greater reliance on a progressive state personal income tax, an expanded circuit breaker to provide property tax relief, and closing corporate tax loopholes will benefit all New Yorkers with a more evenly shared tax burden.

Unemployment insurance benefits have been a lifesaver for tens of thousands of New York families during and following the economic downturn. Yet, the state's unemployment system has not been updated in over a decade and has fallen behind nearly every other state in the extent to which it replaces lost wages. New York’s average weekly unemployment benefit of $304 replaces only 26 percent of the average weekly wage, putting New York in 48th place compared to other states.

New York should link its economic policies to raising wage levels so that workers can start to bridge the wage-productivity gap and provide a modest boost to consumer spending and job growth. New York could raise the state minimum wage in stages to restore the purchasing power of its low-wage residents. The wage now currently is worth 26 percent less than it was in 1970. Eighteen states and the District of Columbia have minimum wages higher than New York’s $7.25 minimum. For its part, New York City could expand its living wage ordinance to companies receiving significant city economic development assistance.

Taken together, these measures represent important steps to increase jobs and begin to counter the substantial income disparities that have built up in New York and elsewhere in the U.S. over the past 30 years.

James Parrott is deputy director and chief economist of the Fiscal Policy Institute (www.fiscalpolicy.org). He has been studying and writing about the New York economy for over a quarter century.

Public Cuts, Private Reluctance Could Slow Growth in Green Jobs

Back in 2009, as the country was in the thick of an economic calamity, President Barack Obama pumped $5 billion into the Weatherization Assistance Program to help mostly low-income families improve their homes' energy efficiency. New York's program, which receives funding from the U.S. departments of Energy, and Health and Human Services, spent $65.8 million this year to help households throughout the state weatherize their homes for maximum energy efficiency. And last week, Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed a bill that should create more green jobs by allowing homeowners to finance energy enhancement through their utility bills.

With unemployment seemingly stuck at more than 9 percent nationally, the green jobs sector could provide a rare bright spot. Government has tried to give it a boost. And with New York City home to approximately 900,000 buildings, it would seem to offer plenty of opportunity for New Yorkers to get work in the weatherization field, while simultaneously helping the city reduce its carbon footprint.

Those in the weatherization industry, though, say the private sector still has not caught up with the opportunities produced as a result of state and city policy. Meanwhile, the recent deficit reduction compromise and other budget cuts threaten government funded energy and job programs, leading some to question when environmentally friendly jobs will fulfill their promise.

A Silver Bullet?

Obama has frequently said that investments in the "green economy" -- services and industries that produce or use renewable materials -- will help revitalize the country's overall economy. During the recession and the slow recovery, the green jobs sector has created crucial employment opportunities in areas such as recycling, clean energy production and manufacturing and deployment of green cleaning products. In New York, federal and state funding for the weatherization program provides jobs for people who might otherwise be out of work and helping lower-income people save money on heating and cooling their homes.

It has also helped create work for people who find it particularly difficult to find jobs – those who have been in prison.

John Valverde, director of the Green Career Center at the Osborne Association, said his organization helps the formerly incarcerated reenter the workforce as productive citizens. It runs a weatherization program, sending participants to Solar One and the Association for Energy Affordability -- both nonprofits -- for green training.

"We realized that with energy efficiency benchmarking and upgrades stipulated by the Greener, Greater Buildings Plan, we could design a training program to match the basic carpentry and electrical training the formerly incarcerated learn in correctional facilities, thereby providing skills participants could learn quickly rather than over four years in college," Valverde said.

Ismail Ocasio, manager of training development at Solar One in Long Island City, said that trainees are taught building science theory to help them understand buildings' energy flow. They then learn the hard skills, such as how to electrically retrofit a building, air seal cracks and apply cellulose (recycled newspaper) into walls.

The Fortune Society, which also works with former prisoners, said it increasingly emphasizes skills such as weatherization to reflect changes in the job market. "We've offered training for jobs in the social services sector, but we want to build out a 'hard skills' model so that our participants can find jobs in the growing green sector," said Stanley Richards, senior vice president of program.

Into Crawlspaces and Attics

The term "green jobs" tends to summon up images of a technician attending to a gently turning wind turbine in a sprawling green field under a deep blue sky. But the reality is not quite so picturesque.

"Weatherization work is not sexy work," said Valverde of the Osborne Association. "The graduates from our green training programs have to work in the heat and cold in crawlspaces, basements and attics caulking windows and insulating."

Nelson Cordova, who was imprisoned for 14 years, graduated from Osborne's weatherization training program. He earns about $20 per hour working in Yonkers, commuting two hours each day to and from Brooklyn.

"It's hard work, especially in the heat wearing a Tyvek suit to protect me from grime and dirt," said Cordova. But he said he feels good when he helps low-income elderly homeowners save money on their energy bills. “I'm just so happy I'm making a living after prison," he said.

Valverde said he thinks the program will pay numerous dividends. "Many of our candidates come from high crime areas in the Bronx, Brooklyn and Poughkeepsie" that, he said, are also "subject to environmental injustices such as toxic landfills and toxic emissions from heavy truck usage. The promise of weatherization work and green jobs is that they provide the mechanism to produce leaders in the community so that they give back to rather than harm the community, and at the same time do work that’s positive for the environment."

Osborne has graduated about 200 students from its weatherization-training program since March 2010. According to Valverde, the organization has a 58 percent job placement rate thanks to a network of contractors.

Osborne offers a wage subsidy to help persuade private contractors to hire the graduates, paying 75 percent of the graduate's wages for the first three months of work. Valverde said that the incentive has helped to cultivate relationships with contractors, who continue to employ Osborne graduates after the three months.

The organization also provides career coaching services, networking events and business classes, and runs a listserv to inform graduates of job openings or union apprenticeships.

Where the Jobs Are

Despite these and other efforts, green jobs still account for a small percentage of the work in New York City. As of 2010, research by by Lesley Hirsch, director of the New York City Labor Market Information Service at the CUNY Graduate Center, found, 75,000 "green workers" worked in four industries here: construction trades, building services, professional services and component manufacturing. In every one, the green jobs account for a very small percentage of total employment. For example, Hirsch notes that 137,840 people work in building services, but only 28 percent (37,940) are green workers. But she noted that that number should grow as city legislation sets energy efficiency benchmarks and requires upgrades.

Jobs also should be created when the state's funding becomes available for the Green Jobs-Green New York program to provide homeowners and commercial properties $13,000 and $26,000 in loans for retrofitting.

Devashree Saha, senior policy analyst at the Brookings Institution credits the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority with committing $22 million since 2008 to train 13,000 New Yorkers in 40 different training centers throughout the state.

Her report Sizing the Clean Economy, found that the New York metropolitan area leads all major metro areas in the country in the number of green jobs, with 152,034 as of 2010. Of course, one reason for that is that New York in the nation’s biggest city. Because her team used a broader definition of green jobs than Hirsch did, the city's mass transit system leads the green jobs pack with 60,000 workers out of the total.

For green jobs to really gain a foothold the private sector needs to jump on the weatherization bandwagon. Saha noted the business incubator model that has helped spawned clean energy companies in the city could boost such effort. Two firms -- Rentricity and Sollega, both owe their starts to the NYC Accelerator for a Clean and Renewable Economy housed at Polytechnic University.

A Murky Future

The role of the private sector could be particularly vital in the light of federal spending cuts and tight state and local budgets.

Obama wanted $320 million for the Weatherization Assistance Program. The House Energy and Water Appropriations Subcommittee wants to drastically reduce the budget to only $33 million, according to Rebecca Stewart, projects coordinator for the National Association for State Community Services, which helps states reduce poverty.

Stewart noted that the national weatherization program may well go belly-up if the cuts make it through the Senate. "This year's funding is $174.3 million, but the combination of losing ARRA [American Recovery and Reinvestment Act] funding come March 31, 2012 and a 2012 budget of $33 million would effectively dismantle the program," she said.

Meanwhile a few green businesses are starting to expand – and create jobs for people who might otherwise not have work.

Gary Grecco, owner of EnergyPro Insulation in Staten Island, said since he started doing weatherization work three years ago business has grown 20 percent annually. He participates in the Enhanced Home Sealing Incentives Program offered by the National Grid, which pays homeowners for the cost of completing an energy audit of their homes done by a private contractor.

Greco has yet to hire someone who is formerly incarcerated and has graduated from a workforce development training program, but said he would consider it in certain circumstances. "If I have a job in an affluent section in Staten Island I will not send someone formerly incarcerated because that person may not relate to the homeowner. But I will send that person if the work is in a low-income area," he said.

Jim McDaniel, vice president of operations at Prospect Development and Construction in Brooklyn, said his company already employs four weatherization workers who have received help from the city's Department of Youth and Community Development. As to whether he would hire a former prisoner, McDaniel said he would consider it "as long as the person showed interest and worked hard, because I believe in second chances."

Bloomberg Poverty Policies Cut the Public, Boost the Private

In early May, the Bloomberg administration held a kick-off event to celebrate a five-year, $100 million expansion of the mayor's anti-poverty pilots, now called the Social Innovation Fund Learning Network.

Less than two months later, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the City Council agreed on a budget for fiscal year 2012 that included the 10th consecutive cutback of anti-poverty agencies.

The two events highlight the unreal nature of the Bloomberg administration's approach to fighting poverty. As the mayor continues to expand his privately-funded anti-poverty pilot program, begun in 2006 to other cities, he steadily cuts the budgets of the city's own anti-poverty agencies.

His much-heralded private efforts have had little to no effect on poverty in New York and seem unlikely to have any significant impact in the future. Many are modeled on programs in developing countries like Mexico, Colombia, and Bangladesh and involve giving cash to poor people in return for certain behaviors, making sure their children go to school, for example, or taking them to a doctor. While these efforts -- called conditional cash transfers -- have been extensively researched, two recent surveys offer little evidence that such tactics might help the poor in urban America.

The weak premise that cash-incentive, self-help pilot programs will alleviate poverty in New York City has effectively obscured the real conditions of poverty in the city: unemployment, limited childcare, poor schools and job training, etc.

Certainly the poverty rate shows no signs of abating. After largely neglecting poverty for his first term, Bloomberg announced an anti-poverty initiative in 2006. In the time since, the poverty rate has remained virtually unchanged, with about 20 percent of city residents classified as poor. In 2009, 10.5 percent of New Yorkers lived in deep poverty -- with incomes less than half the poverty level, or below $10,500 for a family of four. At the same time, the wealthiest New Yorkers have become ever richer, giving New York the greatest gap between rich and poor of any major city in the county.

Cutting Public Programs

While the number of poor people has not decreased since the mayor announced his anti-poverty initiative, the funding to get them out of poverty has. The 2012 budget agreed to by the City Council and mayor is, at $66 billion, about $5.2 billion smaller than it would be without those cuts. The city faces real budget problems, but anti-poverty programs are not only not a priority; they are a target.

Determining the impact of these cuts on anti-poverty programs is difficult. The Mayor's Management Report, intended to provides a measure of the effects of such cuts, offers no help. But a simple analysis of cutbacks in the city workforce since the budget reduction began offers some clues.

Agencies that provide basic city services to poor and working class New Yorkers, including education, child care, health, homeless services, housing and parks, have lost a disproportionate number of workers -- 6 percent to more than 26 percent of their staffs. Yet the police department, in contrast, has lost fewer than 3 percent of its uniformed officers, and the corrections department has actually increased its uniformed staffing by over 2 percent.

Changing Headcounts

Uniformed Officers

|

Agency |

Headcount |

Headcount |

Change |

Percent Change |

|

Corrections |

8,225 |

8,404 |

+179 |

+2.2% |

|

Police |

35,284 |

34,309 |

-975 |

-2.8% |

|

Fire |

11,618 |

10,779 |

-839 |

-7.2% |

|

Sanitation |

7,580 |

6,822 |

-758 |

-10.0% |

Other City Services

|

Agency |

Headcount |

Headcount |

Change |

Percent Change |

|

Education |

97,300 |

90,367 |

-6,933 |

7.1% |

|

Children's Services |

7,103 |

6,529 |

-574 |

8.1% |

|

Health and |

|

|

|

|

|

Housing |

694 |

536 |

-158 |

-22.8% |

|

Parks |

6,520 |

4,791 |

-1,729 |

-26.5% |

Source: NYC, OMB, Fiscal 2009, Fiscal 2012 Adopted Budgets.

Overall, the city-funded workforce has declined from 269,461 in May 2008 to 253,850 in 2012, a loss of 5.8 percent. Although it is not clear what the savings from this downsizing are, if we assumed $65,000 savings per worker, the savings would be roughly $1 billion a year. Across agencies there is wide variance, both among uniformed workers and among anti-poverty staff. There is certainly no evidence of shared sacrifice.

There is, however, a much greater variance in several agencies that serve poor and working class New Yorkers. The above table shows that headcount cuts ranged from six to 26.5 percent.

The rhetoric of the mayor's privately funded anti-poverty pilots stresses the importance of education, child care, training, and preventive health measures in moving poor youngsters and young adults out of poverty. Yet the mayor's budgets for the city cuts these very services.

For example, even though the new budget saved the jobs of 4,100 teachers the mayor had planned to lay off in 2012, the Department of Education nevertheless has lost nearly 7,000 teachers over the past four years, a 7 percent cutback in the teaching staff. The focus on the threatened layoffs has repeatedly obscured this attrition, a product of not replacing teachers who retire or resign.

These losses, though, have an effect on schools. The Independent Budget Office recently found that average class sizes in grades kindergarten through eight increased for three consecutive years, rising from 23.0 students per class in the 2007-2008 school year to 24.6 in the 2010-2011 school year.

The Administration for Children's Service, which oversees preventive services and childcare services, has lost 8 percent of its city-funded staff in four years, while the health department has lost over 9 percent. The parks department, which has developed job-training and entry-level jobs, has lost more than a quarter of its city-funded positions.

Then there is the Department of Homeless Services. Two time-limited rent subsidy programs have been abandoned. The Coalition for the Homeless estimates it will cost some $370 million to find shelter for those losing their subsidies. Furthermore, staffing in both the homeless services and housing agencies have been cut, by 6 and nearly 23 percent respectively over four years.

Amid these changes, the Coalition for the Homeless' 2011 report found an all-time record 113,553 homeless people -- including 42,888 children -- slept in city-funded shelters in fiscal 2010, a 37 percent increase from fiscal 2002, the mayor’s first year in office.

Taxing the Poor

The revenue side of the budget shows the same bias against the poor. City tax policy is far less progressive today than it was in the 1990s, when the top personal income tax rate was 4.46 percent. From 2003 to 2005 it was 4.45 percent. But in 2006 it reverted to 3.65 percent where it remained as the series of budget cuts unfolded. (The state added a top rate of 3.876 in 2010 for those earning over $500,000.)

Even a partial return to earlier, more progressive top rates – a 4.264 percent rate would have raised $450 million in 2012, according to the Independent Budget Office's Budget Options report. This money could have seriously slowed the cutbacks in education and social welfare programs. But the mayor's only tax revenue initiative in the past four years was to raise the city sales tax -- the tax that most disproportionately hits poor New Yorkers -- from 4.0 to 4.5 percent in August 2009.

The Private Effort

All this stands in sharp contrast to the mayor's focus on anti-poverty pilot programs. This remains essentially a non-governmental effort: funded mostly by the philanthropic Mayor's Fund to Advance New York City, designed and evaluated by MDRC, a national research organization, implemented by non-profit community groups, and managed by the Center for Economic Opportunity, a small unit in the mayor’s office. The pilots will now be introduced in seven other cities as well as New York.

What is the point of those efforts?

A recent New York Times article noted that a large number of Bloomberg administration pilot programs, especially in transportation, were designed to avoid public scrutiny. For instance, a 10-school education pilot, called the Innovation Zone, which emphasizes online learning, is set to expand to hundreds more schools, at a cost of $100 million, in spite of at least one report that warned of negative parent responses.

In 2007, Deputy Mayor Linda Gibbs said the mayor used private funds for his first round of poverty programs "to protect it a little bit from the criticism that we knew would come with the initiative."

More significantly though, the mayor may be turning to private funds because the surviving pilots have little or nothing to do with city policy or programs – and have had little to no effect. They are, rather, a curious attempt to take some very preliminary findings from two decades of narrow economic research on poverty in developing countries and make them relevant in urban America.

Innovation and Evaluation

The intent of the Social Innovation Fund Learning Network, which oversees the projects, is two-fold. It is intended to develop new, promising programs and to evaluate them using a scientific technique developmental economists called randomized control trials. Under this method, some individuals participate in the program and others, the control group, do not. If the programs work, its participants will benefit and those in the control group will not.

On the first score – innovation -- four of the five pilot programs sponsored by the mayor and other private funders in the eight-city network (New York, Cleveland, Memphis, Newark, San Antonio, Tulsa, Youngstown and Kansas City, Mo., ) are hardly groundbreaking.

Jobs-Plus will take job-training services into public housing developments; SaveUSA will show poor families how to save money; the Young Adult program supports internships for young adults; and Work Advance is a sector-focused, skills-building workforce program. They all sound promising, just as they did in the 1960s. It’s the conditional cash transfer program, the Family Rewardspilot, that raises the most doubts. As first tried in Mexico in 1997, mothers were paid if their children attended school regularly. Several other countries, including Colombia, Jamaica and Turkey, have adopted variations of this program.

In the mayor’s 2007-2009 version, this meant paying families and some older students for achieving certain goals, such as school attendance, school graduation, making dental appointments, having health check-ups, etc.

The Scientific Background

The testing of Family Rewards and the other pilot programs will follow the pattern described by economists working in several developing countries. Two recent books provide comprehensive (and readable) reviews of this research over the past two decades: Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty, by Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo, and More Than Good Intentions: How a New Economics is Helping To Solve Global Poverty, by Dean Karlan and Jacob Appel.

Their titles suggest the problem of relevance for the mayor's pilot programs. One assumes fighting global poverty in Mexico, India, and Bangladesh is not going to be the same thing as fighting poverty in the Bronx or Kansas City. And indeed the two books have no specific suggestions about how the anti-poverty results in developing countries might apply to urban areas in advanced economies.

The use of the randomized control trials has, nevertheless, proved useful in measuring the success of such programs as micro-lending and micro-saving in developing countries. In fact, MDRC's nearly 400-page evaluation of the mayor’s 2007-2009 Family Rewards program showed the effectiveness of some of the cash incentives, such as for school achievement and seeking preventive health, although "the effects that have been observed so far are generally not large."

But the two books raise a larger question that may help explain why Bloomberg and the private foundations are interested in such a project. Banerjee and Duflo see two competing schools of thought here – two ideologies really. One, represented by the economist Jeffrey Sachs at Columbia, says developing countries need foreign aid to overcome their countries' economic problems. In other words, government is key.

The other side, represented by economist William Easterly at NYU, sees the free market as the answer. For this school, say the two authors, "The best bet for poor countries is to rely on one simple idea: When markets are free and the incentives are right, people can find ways to solve their problems." Changing human behavior is key.

Bloomberg's initiatives seems to arise from a version of the Easterly thinking. They address poverty by focusing on the individual, not by government action. The hope then is that small amounts of money will serve as incentives that empower poor individuals to improve their economic condition.

As for the research itself, Easterly himself cites its limitations. Randomized control trials, he wrote, are "infeasible for many of the big questions in development, like the economy-wide effects of good institutions or good macroeconomic policies. … Embracing RCTs has led development researchers to lower their ambitions."

Bloomberg's embrace of this type of program demonstration is odd not only because it surfaces so late in his tenure and has so little to do with the city’s day-to-day public programs, but also because it incorporates no long-term goal for the city. It may, though, simply indicate his ideological preference for private, not public, answers to public policy issues.

The MDRC evaluationhinted at the anti-poverty project's limitations: "As a short-term intervention layered on top of an already well-developed social safety net, Family Rewards serves as a supplemental program rather than as the core welfare system, as in Mexico and a number of other countries."

The social safety net may be less well developed in 2012 and beyond. But "short-term intervention" and "supplemental program" seem rather modest goals for a national experiment – and for a mayor who has set such lofty goals in other areas, such as public health and environmental sustainability. In any case, in New York, the second stage of Family Rewards has shrunk dramatically. A program that served 2,400 families from 2007-2009 will serve only 600 New York families over the next five years.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.