City Report Largely Mute on Budget Cuts, Recession

Here we go again: more mid-year city budget cuts, another Mayor's Management Report that dodges management issues, and another contracting report that celebrates rather than analyzes privatization.

On Sept. 21, Mayor Michael Bloomberg – less than three months after the council’s adoption of the 2011 budget -- told city agency heads to cut their budgets 5.4 percent this fiscal year and by 8 percent for next year -- half those amounts for the education, police and fire departments.

This action, reducing next year's budget by $1.2 billion, is the mayor's ninth such plan in less than three years. The eight earlier plans -- all ultimately authorized by the City Council -- have had the fiscal effect of over $3 billion in spending cuts in 2011 alone.

The day before sending this directive, the mayor quietly released the city-charter mandated document that is supposed to provide a review of these budget-cutting years, the Mayor's Management Report for fiscal year 2010. (As noted in an Independent Budget Office blog, only one city daily noted -- with 145 words -- its release. Gotham Gazette cited and linked to the report.)

A companion report, the annual agency contracting report was released separately and even more quietly. While full of data, neither of these reports provides much of a framework for a new round of budget cuts. At best, they provide some clues that not all is as rosy in the city as advertised.

Accountability by Press Release

The mayor's voice, absent in the management report itself, surfaces only in a couple of sentences in a press release, which reports an "overwhelming record of improvements in service delivery" during his administration. Even with the eight rounds of cuts, "key services" have "generally been maintained and in some cases enhanced."

The press release itself apparently stands as the backup for the mayor's claims. It features 135 "Critical Indicator Performance Indicators" from the report -- organized in six tables (public safety, quality of life, public health, education, human services, economic development), with not a single comment about any individual indicator.

The six tables themselves tell some tales, especially about social and economic conditions in the city in 2010. But few of the indicators actually measure performance. And some that do -- especially in three of the mayor's priority areas -- public safety, homeless services and education -- show mixed or negative results, particularly in the recent years of cutbacks.

Citywide crime statistics, for example, over the first eight years of the Bloomberg administration show declines in all seven major felony areas. (The report does not mention recent media accounts of data manipulation by the police department.) And crime in the transit system is down by nearly 50 percent over nine years. But the past year saw increases in four of the citywide seven felony measures: murder, rape, felonious assault and burglary.

The average number per day of homeless families in shelters skyrocketed after 2001, from 5,563 to 9,938 in 2010, a 79 percent increase. That includes an 8 percent rise in the past year. The number of single adults in shelters in 2010 (7,167) was roughly the same as in 2001 (7,187), but there has been a 10 percent increase during 2010.

The test results for high schools show some progress: The number of students passing Regents exams in all five subject areas was substantially higher in 2009 than in 2001. High school graduation (in four years) rates between 2005 and 2009 increased substantially -- from 46.5 percent to 59.0 percent.

But the test results for elementary and middle schools are negative. The percent of students in grades 3 to 8 meeting or exceeding standards in English Language Arts was 42.4 percent in 2010, up from 39.0 percent in 2001, but down from 68.8 percent in 2009. In math the percent in 2010 was 54.0 percent, up from 34.0 percent in 2001 but down from 81.8 percent in 2009.

In a brief note, the management report explains that because of the "recalibration" of the state test results, the drop in reading and math scores "does not mean that students' performance in English and math declined from the previous year -- only that the students of New York City are now being held to a higher standard."

In a rare hint of emotion, the note concludes, "Scores that may have been proficient a year ago may fall short of the bar this year, but the department remains committed to ensuring that all students meet and exceed the standards set by the state, wherever the bar is set."

The negative effects of budget cuts in education are perhaps most obvious in the class-size statistics. Although average class size in grades K-8 in 2010 (24.2 students per class) is slightly lower than it was in 2001 (25.1), average class size increased in each grade in the past year from 23.5 in 2009.

None of these performance indicators -- positive, mixed, or negative -- are discussed in the news release.

Social and Economic Indicators

The most revealing data among the 135 indicators in the press release, however, are not the few performance measures, but the social and economic indicators.

Although the release blames the budget cuts on a "national economic downturn" -- ignoring the mayor and City Council's reluctance to consider new revenues to minimize cuts -- the press release doesn't speak to the enormity of the social and economic fallout.

Unemployment, for instance has increased by 80 percent during the past nine years, 40 percent in the past year alone. City unemployment was 5.6 percent in 2001, 6.2 percent in 2005, 7.2 percent in 2009, and 10.1 percent in 2010.

Perhaps the most disturbing data are the food stamp numbers. In 2010, over 1.7 million New Yorkers received federal food stamps, more than double the number of recipients in 2001. With a current city population of about 8.4 million, that means more than one in five New Yorkers now receives food stamps. While the city has, at times, attributed some of the increase to better outreach efforts, the report does not comment on that.

The great bulk of recipients -- over a million -- do not receive welfare assistance. In fact, the number of food stamp recipients who are not on welfare has increased almost five-fold since 2001. A puzzling fact not addressed is that the number of cash assistance recipients steadily declined from 2001 to 2009, from approximately 500,000 to 346,100 in 2009 -- and only slightly increased in 2010 to 346,300.

Program and Human Consequences

In terms of recent budget cuts, at least two of the human services indicators suggest problems: The number of children receiving contracted preventive services -- programs offered by private agencies to monitor children and help troubled families remain intact -- increased from nearly 24,000 in 2001 to 31,752 in 2009, a 33 percent increase, but in the last year the number has dropped by 6 percent, to 29,945.

The number of children eligible for adoption who are actually adopted rose in the first half of the Bloomberg administration, from 64.1 percent to 76.7 percent. But since 2005 the percentage has dropped back almost to where it was in 2001, to 64.9 percent in 2010.

The management report includes total human services contract dollars in agencies, and there are some interesting -- an unexamined -- numbers. In the Human Resources Administration, for instance, during the past three years of budget cutting, contracts with non-profit service providers held constant ($623 million in 2008, $622 million in 2011), which, adjusted for inflation, means a real cut.

The Department of Homeless Services, with demand increasing in spite of the mayor's efforts to reduce homelessness, saw contracts with the non-profit providers who provide the bulk of the city’s shelter services, increased in the same three years, by nearly 12 percent, from $577 million to a projected $644 million in 2011. Given the rise in homelessness, that seems a very modest increase.

Two other agencies, whose services are almost exclusively provided by small neighborhood non-profits, show substantial declines: The Department for the Aging saw contract funding drop from $229 million in 2008 to a projected $204 million in 2011, an 11 percent cut. Contracts at the Department of Youth and Community Developmentdeclined from $288 million in 2008 to a projected $263 million in 2011, a 9 percent drop.

The Contracting Report

The report that could inform such shifts in agency contracting is the city's agency procurement indicators report for 2010, but it provides no help in understanding the impact of recent or projected cuts in contracts with non-profit agencies in human, health and social services.

Early in his administration, the mayor separated reporting about city contracting in the city's operating budget (representing nearly $10 billion of a $63 billion budget) from the Mayor's Management Report even though several city agencies -- youth, aging, homeless services, cultural affairs, for example -- are mostly contract agencies. The Mayor's Office of Contract Services now issues a separate report once a year, covering both operating and capital budget contracting.

The transfer of reporting to the contract services offices has centralized administration and oversight of contracts. In fiscal, legal and administrative terms, this has many advantages. And the report has a good deal of useful information, especially on contracting opportunities and procedures. It even offers some analysis of a few identified problems (contract-processing delays, change orders, and nominal progress on opportunities for minority- and women-established company).

But the report does not provide accountability on substantive matters. For example, some 1,836 non-profit human service agencies were awarded $2.3 billion in contracts in 2010, with 536 of the contracts for more than $1 million.

The results? Over 1,000 non-profit leaders and staffs attended 15 training sessions. Some 82 ($1 million-plus) contracts were reviewed. And 96 percent of all city vendors received at least a "satisfactory" rating in 2010.

Left unexamined are some important questions: For instance, how did a city contract intended to save money on tracking the hours of city workers grow from a projected cost of $68 million to a projected $738 million, as reported by the city comptroller in March. How does a September agreement between the comptroller and mayor seek to resolve the issue?

In another March audit, the comptroller found that the Department of Homeless Services paid $152.7 million to "non-contracted" service providers based on an "honor system." Auditors found a "lack of internal controls and monitoring of service providers" and concluded, "Providers did not transition clients to permanent housing in a timely manner." One client remained in a shelter for six years, costing the department $234,397, another in a hotel for over four years at a cost of $118,933.

Because of a technicality in state law, the management report has no obligation to review contracting in the Department of Education. Thus there is no comment on a 16 percent increase in the department's contract budget, from $3.262 billion in 2010 to a projected $3.781 billion in 2011 (nearly 40 percent of the $10 billion operating contract budget), as reported by the mayor's Office of Management and Budget. (The Independent Budget Office and city comptroller have been authorized to analyze education data, and the budget office has already released studies.

Budget Prospects

The city faces big fiscal problems. City Comptroller John Liu in his July report on the adopted budget for 2011 warned (presciently) that there could be a $690 million shortfall in this year's budget. He awarned of future deficits that could reach $4 billion in 2012, $5.1 billion in 2013 and $5.35 billion in 2014.

However, the mayor's repeated use of his administrative powers to cut agency budgets outside of the standard budget cycle ignores alternative strategies, minimizes the role of the City Council, and denies the public any voice in the budget process. At the same time, the paucity of useful fiscal information in the Mayor's Management Report and the contracting report makes it difficult, if impossible, to measure the impact of earlier budget decisions.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.

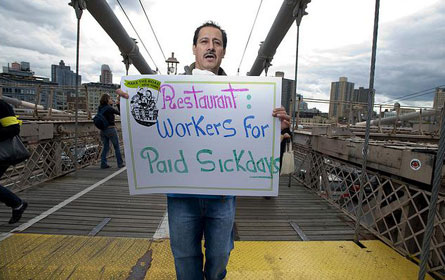

Quinn Rejects Paid Sick Leave Bill

Council Speaker Christine Quinn said Thursday she would not support legislation to require paid sick leave for every worker in New York City, effectively killing the proposal and giving a boost to businesses that lobbied vigorously against it.

Citing the economy, Quinn said the city could not afford to put another mandate on small businesses that are already struggling to make ends meet.

"It would be a great thing if we could mandate every worker got paid sick leave," said Quinn, dressed in a sharp black suit. "But if we do that and it causes people to in fact lose their jobs, what benefit have we actually forwarded?"

The legislation (Intro 97), which was initially introduced by Councilmember Gale Brewer in 2009 and has languished ever since, would require businesses with fewer than 20 employees to provide five paid sick days per year per employee. Businesses with more than 20 employees would have to provide nine days off. Any other paid leave could be counted towards the sick time minimum under the current version of the bill. According to a council analysis, it would have cost businesses between $700 and $1,200 a year per employee.

A veto-proof 35 members have signed on in support of it.

The move not to support the proposal shocked some supporters of the legislation and of Quinn, a presumptive mayoral candidate in 2013 who built her legislative record on fighting for working class New Yorkers.

Both supporters and opponents of the proposal said the speaker's decision would likely set her apart from the other potential Democratic candidates for mayor, many of whom are drifting left.

In killing sick leave, Quinn has become a friend of small business, but has simultaneously angered some of the city's progressive leaders, like one of the bill's strongest supporters, the Working Families Party.

"The first possible woman mayor has just turned her back on a critical but modest lifeline that families around the city need -- a stunning abandonment of working mothers and parents and the progressive women who have supported her from day one," said Donna Dolan, chair of the NYS Paid Leave Coalition, in a prepared statement. "Our efforts to make the Paid Sick Time Act a reality are far from over.”

Sick Goes to Dead

In defense of her position yesterday, Quinn said she did not turn her back on anyone.

Standing alone behind a podium in a standing-room only conference room downtown, Quinn, confident and sharp-spoken, said she had struggling small businesses in mind when she came to her decision.

"There are businesses on the brink, and they fear any new cost will put them under," the speaker said during a press conference that lasted barely 20 minutes.

For months, if not years, opposing sides of the sick leave fight have dueled over numbers, economic impact and job growth. One study, commissioned by the Partnership for New York City which opposed the bill, put the legislation's cost at $789 million a year. Another conducted by the Drum Major Institute, a major supporter of the bill, said it would not affect the city's job growth.

Supporters of the bill looked at similar laws in San Francisco and Washington D.C., citing their success. Meanwhile, detractors pointed to the city's nearly 10 percent unemployment rate and staggering economy.

Nearly all of the other Democratic mayoral hopefuls, including Public Advocate Bill de Blasio, Comptroller John Liu, Borough President Scott Stringer and Rep. Anthony Weiner, have voiced support for the legislation.

Ultimately, Quinn said a compromise could not be reached.

Brewer disagreed. She said calling it quits was premature and a deal was attainable. But Brewer said she would not use the council's rules to bring it to the floor for a vote without the speaker's support -- a rare but doable process.

Nonetheless, Brewer and other members of the City Council have vowed to continue to fight for the sick leave bill.

"It's not dead," Brewer said. "I have three more years on the City Council. I've been in this game for a very long time. I will not let it die."

But already some members appear to be backing away from the proposal.

Councilmember James Sanders Jr., who chairs the council's Committee on Civil Service and Labor, where the bill is slowly drowning, said he plans to sit down with the speaker to hear her out.

"I have further questions about [the speaker's] position," said Sanders, who is listed as a sponsor on the bill. "She may have information that I don’t have."

2011 to 2013

Some political observers see Quinn's decision as smart.

In the 2009 election, both Liu and de Blasio sailed into office on the backs of the Working Families Party. By siding with small business on this fight, Quinn could potentially receive their support come 2013.

"This allows her to become the friend of small business, which creates an area that the others really haven't broached," said political consultant Hank Sheinkopf. "She has to appeal to those folks if she’s gonna be mayor."

In business circles yesterday, Quinn's move was applauded and called courageous.

Quinn's decision also evokes the position of the city's current chief. Mayor Michael Bloomberg has said the approval of a paid sick leave bill would be "disastrous."

Quinn, however, vehemently denied her decision had anything to do with political motives.

"I have to go to bed tonight as the speaker of the New York City Council," she said. "I have to go to bed tonight knowing that I made a decision that was not easy based on the requirements of the job that I hold."

The decision she made could make the job she has now more difficult. Many of the new members who joined the council in January were elected with a promise to get paid sick leave approved.

Some of them aren't ready to give up.

"I will say I think it shows how important the Progressive Caucus is," said Councilmember Brad Lander, who co-chairs the council's newest faction. "We clearly need to keep pushing hard and working for public policy that may make life better for hard working New Yorkers."

Can a Comptroller -- Any Comptroller -- Fix New York State's Budget?

Try to catalog how many times the Republican candidate for state comptroller, Harry Wilson, used the term "under investigation" to describe Democratic incumbent Tom DiNapoli during their Oct. 4 debate. You will likely lose count. But with one release from Attorney General Andrew Cuomo’s office announcing DiNapoli is no longer under investigation, the focus of the contest between the two men -- and of Wilson's attack -- changed.

With the potential scandal evidently out of the way, perhaps the candidates will now focus on other differences between them: what effect, if any, the comptroller can have in navigating the state through this fiscal crisis and how to manage the huge state employee pension fund.

Both candidates have tried with all their might to label each other with the negative baggage of their backgrounds.

Wilson says DiNapoli is an Albany insider picked by the legislature to oversee its spending and he is accustomed to pay-to-play politics.

DiNapoli charges that Wilson has spent years on Wall Street and says that Wilson comes from the kind of reckless financial culture that landed the country in its current financial emergency.

Comptroller as Budget Cutter

As he campaigns, Wilson, who served on President Barack Obama's auto industry task force, hammers away at the state's precarious fiscal situation and says the government must curtail spending. He insists that DiNapoli has not done enough to attack government expenditures, saying DiNapoli should have audited programs in the budget and pointed out areas that need trimming

Wilson, though, said the state comptroller can do far more than that. "I wouldn't start on April 1 when the budget is due but on Jan. 1. There needs to be a review of all spending. The office should come up with spending cuts. I have the skills to do that. I would work with the governor to create a better budget." Wilson said last week.

DiNapoli said he has been using the comptroller's office as it is designed -- he conducts audits of state spending, announces his findings and tells the legislature and public where he thinks spending could be controlled.

Further, Wilson said, if the proposed budget was not balanced he would not certify it. "If spending and income are out of line then you don't certify," he said. In other words he would reject the plan and refuse to pay out the funds allocated in the budget.

But according to DiNapoli the comptroller does not have the power to certify or not certify. "We have no role in certifying it [the budget]. People have the incorrect notion that we do it," he said. "That is a policy change for the governor and legislature."

The comptroller does get to issue revenue estimates for the state when the legislature and governor can't agree on the numbers. DiNapoli has issued projections that are more pessimistic than those of the governor or the legislature.

But DiNapoli said any direct involvement by his office in setting spending or revenue estimates would jeopardize the office's role as independent auditor. "If we were involved in the process it would create a conflict, reduce our independence and could compromise our auditing ability," he said.

Wilson says that he has consulted counsel on the issue of certification and was told a comptroller could legally refuse to approve the governor and legislature's spending plan. "Mr. DiNapoli said he consulted the attorney general and was told that he can't. But during his campaign against [former comptroller]] Carl McCall, the current attorney general Andrew Cuomo criticized Carl McCall for certifying bad budgets, so he must agree with me," Wilson said.

Gerald Benjamin, professor of political science at SUNY New Paltz, says that, under his understanding of the law, the comptroller has no role in certifying the budget and is not supposed to directly help the legislature or governor come up with their plans.

"The legislature is not required to prepare a balanced budget," said Benjamin. "The comptroller's duty is to perform his own survey -- he can say if he thinks the budget is balanced and say if he perceives any risks on the spending or income side. He can use the position as a bully pulpit. The idea that the comptroller can stop the budget by not paying out is kind of a nuclear option and I don't think it is politically feasible."

Benjamin points out that Article 5 of the state constitution says that the legislature shall not give the comptroller any "administrative duty."

DiNapoli said he has used his office as allowed by state law to weigh in on the state's budget problems. "We have been outspoken and sounded alarms, saying that the budget isn't balanced. It hasn't solved all the budget problems but I am optimistic, given the current climate, that the next governor and the legislature will approach things in a better way," he said.

Wilson, however, said DiNapoli could have done more, and that DiNapoli's loyalties to the legislators who appointed him comptroller have stopped him from seriously examining how they spend taxpayer dollars. DiNapoli also served in the Assembly for 20 years.

"He seemed proud," Wilson said of DiNapoli who told the crowd at the debate how many legislators had approved him as comptroller. But Wilson says that vote ties him to the legislature and he points out that this is the first time voters will get to weigh in on DiNapoli. Both candidates have agreed that they think the comptroller should be replaced by the voters if a similar vacancy should occur in the future.

Wilson suggested he would use audits to put pressure on legislators. "If there is an audit of a spending program that shows serial abuses of spending and it would be embarrassing for legislators if it was aired in public, I will have leverage to change things," he said.

It isn’t clear how this would differ from DiNapoli's approach as he has done many audits.

Wilson said he expects the next governor will want to work with him on putting together a good budget because of the trying fiscal times.

>

Running the Pension Fund

Still, the most controversial issue surrounds the pension fund. The comptroller's office has almost total control of the state's $124 billion pension fund. The fund has been a source of controversy because of the investigation into how the administration of Alan Hevesi, DiNapoli's predecessor, handled the investments. During Hevesi's time in office, placement agents steered the state's money into investments with their friends' companies. Campaign donations also were allegedly a good way to get the state to invest pension cash.

At the time of the debate, word was that Cuomo was investigating DiNapoli's handling of the state pension fund as an extension of the Hevesi probe. DiNapoli was named to his position by the legislature in 2006 after Hevesi was forced to resign.

But last week Hevesi pleaded guilty to taking $1 million in gifts from Markstone Capital Partners in exchange for the state making $250 million in investments with Markstone, and Cuomo's office finally responded to inquiries about an investigation into DiNapoli's office.

"During the investigation, the office reviewed an investment known as Intermedia, which was approved for investment under then-New York State Comptroller Alan Hevesi and increased under Comptroller DiNapoli," read the statement. "The office has concluded our review of that investment and determined that no action is warranted. Mr. DiNapoli is not involved in any investigation or matter in this office."

DiNapoli, in other words, was off the hook.

A few days later, the DiNapoli campaign demanded that the Wilson campaign stop airing television spots that refer to the incumbent comptroller as "under investigation." Wilson's campaign responded saying serious questions remain about how DiNapoli handled the pension fund in his first two years as comptroller.

DiNapoli said he has changed the culture of the fund and has done away with placement agents. "It's not like I just sit in my office with the financial papers and decide we are going to put this much money here," DiNapoli said pointing out that his office has a large staff that reviews investments.

Wilson, however, said it took 26 months for DiNapoli to make any reforms in how his office handled the pension funds. "For 26 months the process went on with placement agents," said Wilson. "Who did he meet with?"

According to Wilson, DiNapoli had one meeting "with two people who have paid settlements" arising from their involvement in the pension fund scandal.

Wilson said his campaign has tried to use the Freedom of Information Act to try to gain access to DiNapoli’s schedule, "but we were told on that on Oct. 28 they will tell us how much it will cost," that would leave the Wilson campaign with little time to explore the calendar and investigate who DiNapoli met with.

"The schedule is FOILable," said DiNapoli. "Journalists have gotten it. My opponent makes things more complicated than they have to be.”"

"Are you kidding me, Mr. DiNapoli?" asked Wilson. "If you don’t have anything to hide then show us your planner."

Where to Put the Money

The candidates also disagree about what kind of investment strategy the office should pursue.

Wilson said he would significantly reduce the amount of risk involved in pension investments, putting the money in safer, if less profitable, places.

"I would reduce the risk portfolio. We would have lower returns but it would be better in the long run," said Wilson. "We have to pay retirees come hell or high water."

DiNapoli says that his office has reduced the risk portfolio and by extension the returns on the fund, but he said the size of the reductions Wilson is considering worry him.

"I've heard him talk about reducing it down to a 5 percent return. That would be devastating. It might make it impossible to meet the needs of the pension. The idea that someone from that Goldman Sachs background would reduce the risk is hard to believe. Reducing the returns could lead to an inability to meet the payouts, and that would lead to tax increases, so in a way it would be more risky," DiNapoli said.

During the financial crisis from spring 2008 to spring 2009, the pension fund dropped from $154 billion to around $110 billion during the financial crisis. The fund has rebounded somewhat and is now around $124 billion. New York's fund has been held up in the press and studies as performing much better than funds in other states.

The Race

Before Cuomo's office gave him a clean bill of health, DiNapoli was thought to be the weakest statewide Democratic candidate, despite his lead in the polls. Wilson is the best funded Republican candidate.

"I think we have strong bipartisan support," Wilson said, "Most of his contributions were from unions and PACS, and mine were from individuals."

On Oct. 1 DiNapoli had $1,407,449 on hand while Wilson had $2,626,236. Wilson loaned himself $500,000 and has loaned himself over $2 million over the span of the campaign. A look at DiNapoli’s fund raising filings show significant contributions from unions and political action committees. Wilson's contributions do mostly come from individuals.

Wilson has attacked DiNapoli for taking campaign donations from trial lawyers that represent his office, calling it another example of "pay to play." DiNapoli's campaign says that donations do not influence DiNapoli’s decisions.

Without the investigation hanging over his head, DiNapoli should enjoy a stampede of Democratic endorsements. But even with a recent endorsement by former comptroller Carl McCall, DiNapoli isn’t betting his house that support will pour in. "I'm not as much involved in getting endorsements as I am in doing interviews, speaking to the people. I am more concerned about the stampede of voters in November," he said.

DiNapoli has yet to be endorsed by Cuomo, and Wilson has distanced himself from Republican gubernatorial candidate Carl Paladino. Perhaps both want to look independent.