Eminent Domain Changes Seek to Limit State's Power to Seize Property

When Henry Weinstein bought a commercial building at 752 Pacific St. in Brooklyn 1985 he never expected that 20 years later the government would want to take it away and give it to a developer. Weinstein said that he would be shocked if his land was being taken for a hospital, a bridge or a library. But seeing it seized to make way for Forest City Ratner's Atlantic Yards project shakes his faith in the government. "This is the most un-American thing I have ever experienced," he said.

As New York City has reshaped itself over the past decade, the government has given private developers, such as Forest City Ratner, a powerful tool -- an eminent domain law that allows them to seize land from other property owners. Now some politicians believe the law needs change to protect property owners, such as Weinstein.

Assemblyman Richard Brodsky has put together a package of legislation that would create a commission to review the state's eminent domain process, give land owners fair compensation for their property and establish an ombudsman who would help land owners whose property is targeted by eminent domain. Later this week Sen. Bill Perkins will unveil legislation that he says would change the state's eminent domain laws to better protect property owners. The situation in the legislature, along with a recent appellate court ruling that found the process the state used to take land for a Columbia University satellite campus in upper Manhattan was unconstitutional, could result in the first major changes to New York's eminent domain laws in more than 30 years.

The possibility that the state might finally redo its eminent domain laws -- laws that have remained the same as other states updated theirs -- has caught the interest of civil rights lawyers, property owners and advocates. But developers, real estate interests and some politicians fear changes could make it more difficult for the state to improve blighted neighborhoods in desperate need of investment, infrastructure and jobs.

"Eminent domain is an essential governmental tool that allows for the implementation of important development projects to the benefit of the public at large," Lisa Willner, public affairs manager for Empire State Development Corp., which oversees the state's eminent domain process, said in a statement.

As the legislature considers the law, Weinstein is fighting the taking of his land in court. He acknowledges his legal battle may be futile. "The Empire State Development Corp. rules as kings. We left England to get away from it, but they have the power of a sovereign," he said.

Defining Blight

The state can seize property it determines to be blighted. While the state generally heads up eminent domain projects, in some instances, such as the Atlantic Yards case, the developer's advocacy leads to the state's involvement.

State law defines blight as "substandard and insanitary." Land that is determined to be blighted can be given by the state to another private owner for the purpose of economic development. The state can also use blight determination to make way for public works projects such as roads.

According to attorney Michael Rikon, who represents property owners in the Willet's Point section of Queens, where the city is planning a major redevelopment, the term is so vague that the contractors used by the government basically make up formulas as they go along. "The definition of blight is so broad it could come down to cracks in the sidewalk. Even the mayor's townhouse could be blighted, because it only supports one family," he said.

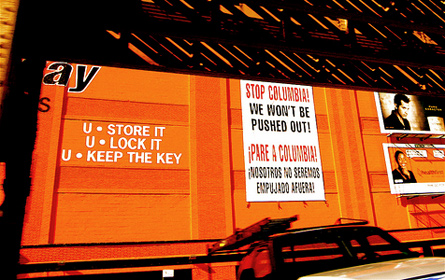

Civil rights attorney Norman Siegel, who represents Tuck-It-Away, a storage company that is fighting Columbia University's expansion plans, agrees. "Basically they are saying if there is a Motel 8 and Hilton comes along and says they can make the property more valuable, then it [the Motel 8] can be declared blighted." Many advocates, Siegel said, have begun saying the land in these cases should not be labeled "blighted," but "coveted."

Siegel calls eminent domain one of the premier civil rights issues of this century. "I really think it is the civil rights issue of the 21st century. It disproportionately impacts poor neighborhoods and people of color. It cuts across partisan lines," he said.

The Eyes of the Beholder

Of further concern to Rikon, Siegel and others is who makes the call. While the board of the Empire State Development Corp. technically determines whether a property is blighted, the agency hires a contractor who is paid millions of dollars to conduct the technical study and write a report. In the case of Columbia's campus expansion, the university and the development corporation used the same contractor, AKRF, at the same time. In the case of Atlantic Yards, AKRF worked for the developer, Forrest City Ratner, and then for the ESDC.

In his ruling against Columbia, Justice James Catterson described AKRF's study of land for the Columbia University project as "idiocy." Saying that the report cites such easily reparable problems as "unpainted block walls" and "loose awning supports" as blight, Catterson wrote in his majority decision, "We questioned [AKRF's] ability to provide 'objective advice' to the ESDC, particularly with respect to its preparation of the blight study."

Advocates say that the ESDC does not have to use AKRF as there are other qualified firms that do the same work. "Our judgment is that AKRF is the most qualified to do this work," a spokesperson for the ESDC told the New York Times.

For the Empire State Development Corp. to use evidence supplied by someone working for the contractor "seems like collusion. It doesn't seem fair, and sometimes perception is more important than fact. The entire process seems blighted," said Perkins.

AKRF defended its conduct. "As a firm of planners and analysts, AKRF's responsibility is the collection and assessment of data in an objective and thorough manner," a spokesman for the firm said. '"Any suggestion that the firm -- widely recognized as a trusted industry leader -- would compromise the quality of its work is incorrect."

"We need a more discrete definition of what is blight, not paid consultants who decide for themselves," said Michael Rikon, the Willet’s Point attorney. Rikon said landowners who have been through the process tell him. 'On the form for blight that consultants use there is one box for blighted and they check it.'" The process is much more complicated than checking a box. But critics say the formulas used almost always lead to the same conclusion -- and it's one that favors developers.

Changing the Process

According to Siegel, property owners only get one, very narrow chance to argue that their property should not be taken away from them. He said landowners in other states have more of an opportunity to challenge decisions. "As far as I can tell New York is the only state where you start at the appeals level," Siegel said. "You get 15 minutes to argue. There is no cross-examination. I think it is a violation of due process."

Perkins and Brodsky hope to address that issue in their legislation.

Brodsky has been working to change the eminent domain law for 10 years. "I don't think eminent domain should be stopped as a useful tool for the public good but with this pattern of private to private transfers I think the current laws may be inadequate. We need schools hospitals and libraries, but person-to-person transfer is an entirely different animal," he said.

One of Brodsky's bills would establish an eminent domain ombudsman "so that normal citizens are not overwhelmed." Brodsky also would like to see owners who lose their land in the eminent domain process be compensated 150 percent of the value of their property. "Anyone forced to hand over their property should share in the profits," said Brodsky. And Brodsky would create a process to review developer's plans to make sure the surrounding community would benefit. He also would create commission to review the scope and effectiveness of current laws, and would like to get rid of the finding of blight all together.

Perkins' bill is said to contain a provision that would change the definition of blight from substandard and insanitary to something more measureable, though what the new standard would be is not yet clear. The senator also would like to include a mechanism to ensure that developers follow up on their promise to the community and to review exactly what benefits the community can expect to enjoy from any project benefited by eminent domain.

The bill contains other tweaks, not yet announced, as well. Perkins says he expects bipartisan support in the Senate as well as help from the Assembly.

Amy Lavine, a staff attorney at the Albany Law School’s Government Law Center who helped Perkins put together his legislation, said it is not intended to disrupt the eminent domain process. "The definition of blight as it stands is very vague. We want to change that. The law increases transparency and accountability in the process. We are not interested in disrupting the process. We just want to make it better." Lavine said.

Thwarted Efforts

Change for New York's eminent domain process has been a long time coming. Over the years, legislators from both parties and both houses have tried in vain to make changes to the law to better protect private property owners only to find their efforts blocked by real estate interests.

In 1974, Rikon took part in a committee charged with making changes to the eminent domain process. "The last time New York changed the law was '77," said Rikon. "What happened was, when we got to the final version the city's lawyers and city corporation counsel eliminated a lot of provisions that they were against. That was 33 years ago. We really need to revise everything step by step."

Most states changed the process and the standards for applying eminent domain following a Supreme Court ruling in 2005. In Kelo v. City of New London [Connecticut], the court decided that a state can take property from a private owner and transfer it to another owner for the sake of economic development. Forty-three states then changed their laws to protect property owners. New York did not.

"Kelo caused a firestorm around eminent domain because people thought eminent domain could only be used for government projects. Kelo said that's not true. It can now be used for public betterment," said Siegel.

In 2009, four years after the monumental Kelo decision, the case was in the news again. The developer that was the beneficiary of the Supreme Court's decision pulled outof the city, and now New London has been left with barren lots.

After 30 years, some observers think Perkins will be able to seize upon public sentiment in an election year and force drastic changes in the law. Brodsky said it would be about time. ""I have been at this for 10 years. I did not jump in after Kelo. It would have been a good time to do this three years ago," he said.

"It could become a firestorm if Bill pushes the issue and more people join in. Folks are angry at politicians. This will be a ripe issue. I think Perkins is sensing that. I know it is certainty ripe with us and with our clients," said Siegel.

On the other side, the real estate industry and other businesses will likely work to preserve much of the state's eminent domain law. They proved this in 2005 in the wake of the Supreme Court's Kelo decision.

"We are alarmed," Kathryn Wylde, president of Partnership for New York, told the state Assembly in 2005, when legislation to alter eminent domain law was being considered. "Without the power to condemn private sites to support economic development projects, New York and other older urban centers could not have kept pace with demands for upgraded infrastructure, modern office facilities and an expanded housing stock."

Serious opposition to changing the process could very well come from Mayor Michael Bloomberg. Advocates say the mayor's office has lobbied hard against such changes in the past. Recently in a New York Times article on the subject of eminent domain reform, Lisa Bova-Hiatt, a deputy chief at the New York City Law Department, said the city would not be opposed to "thoughtful change" but would oppose "ill considered action" sparked by hysteria.

Perkins right now is taking that as a good sign. "We welcome the mayor's help," he said, "I think it would be very valuable."

The governor could represent another obstacle. Following the decision by the appellate court that halted the Columbia expansion, Perkins called on Gov. David Paterson not to appeal the decision. He also asked the governor to institute a moratorium on eminent domain. "I remember standing with the Senate minority leader, now Gov. David Paterson, on the steps of city hall when the Kelo decision was announced. David was very concerned about the use of eminent domain back then," said Perkins.

Five years later, Paterson declined to heed Perkins' request, but Perkins hopes Paterson might still be convinced to join his cause.

Whatever the governor does, Perkins said he thinks the public is on his side. "I'm optimistic the public at this time is calling for reform. They want more reform," he said.

In Kingsbridge: Will Derailing a Bad Project Lead to a Good One?

If you only caught the last act of the show, it would be easy to attribute the City Council’s unprecedented 45-1 rejection of the Related Companies' "Shops at the Armory" to a unique alignment of the political planets. A third-term mayor, seemingly vulnerable after an unexpectedly close re-election; a City Council -- and its speaker -- eager to flex their muscles; and a Bronx borough president whose leadership star is on the rise.

But it took years of dogged community organizing and shrewd coalition-building around a clear vision for the city’s largest armory to position the Kingsbridge Armory Redevelopment Alliance, or KARA, to take advantage of timing, luck and maybe begin re-writing the rules on how major development projects get done.

Having accomplished the unthinkable and by defeating a project backed by the administration, KARA and its allies are gearing up to re-imagine a future for the armory that puts community needs first, doesn’t strangle the neighborhood in traffic and delivers jobs capable of lifting Bronx residents out of poverty.

(The debte over the armory project has renewed the fight over the "living wage" in New York City. For more on the issue and whre ti stand in City Council, see The Living Wage After Kingsbirdge. And to find out where your coucil member stads, go here.)

'We Drove the Process'

In the usual New York scenario, developers tee up their projects, and work quietly with city agencies to line up financing and approvals, as they court political supporters. The New York City Charter-mandated Uniform Land Use Review Process, known as ULURP, requires that major development projects, zoning changes and transfers of city-owned property be reviewed by the affected community boards, the borough president, the City Planning Commission and the City Council. It sets deadlines for each step that create a six-month window for public review. Only the City Council vote and subsequent action by the mayor are binding.

Communities are typically caught flat-footed when the ULURP clock starts ticking: It’s hard to assess the situation, coalesce around a response and put a strategy in play before the 185-day timer runs down. Instead, changes needed for the project to gain final approval from the City Council are often embodied in 11-th hour side agreements, negotiated behind closed doors.

In the case of Kingsbridge, though, Pilgrim-Hunter recounts a 13-year campaign, spanning two administrations, that began when the community and clergy coalition demanded that the armory be redeveloped, and reached a clear and early consensus that redevelopment had to meet community needs.

"If we had a singular advantage, it was that we initiated the process, and we drove the process through to the end,” said Desiree Pilgrim-Hunter, a leader of KARA and the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition.

Their 1995 plan was anchored by schools -- members put the Bronx’s most overcrowded school district together with the city’s largest vacant building and reached the obvious conclusion.

Kwasi Akyeampong, also a community resident and KARA member, recalls, "We had a vision of how the armory should be developed to benefit the community. We were steadfast; we held our elected officials accountable."

The coalition kept the armory high on its agenda, and held rallies, marches and press conferences to ensure that elected officials kept it on theirs as well. The activists pushed for the transfer of the armory’s ownership from the state to the city (1996) and forced the city to spend $30 million to restore the building's 260,000 square foot roof and stabilize its landmarked exterior (2000). They dragged a succession of school chancellors through the building and through the coalition's own research on non-city sources of school funding. Finally, they waited out the slow death of a sole-source agreement between the Giuliani administration and Basketball City (1999-2002) that would have turned the armory into a commercial sports complex.

In 2003, the Northwest Bronx Coalition presented the more market-savvy Team Bloomberg with a mixed-use proposal of its own that would have divided the massive space between schools, recreational space and retail. The coalition navigated the Bronx's challenging political terrain to bring the Department of Education, City Council and Assembly members, then-Borough President Adolfo CarriĂłn and the city’s Economic Development Corp. together on an agreement to put out a request for proposals from developers. In 2005, the Economic Development Corp. announced the formation of a task force, which it pledged to "consult" as it drafted the request for proposals. Community members were heartened, but wary.

Meanwhile, not far away, the same city and state officials were on a very different track as they moved Yankee Stadium through the environmental impact statement and land use processes at warp speed, rolling over near-unanimous community opposition. And a few blocks farther south, the Related Companies were negotiating with Economic Development Corp. to build a shopping mall on the old Bronx Terminal Market site. On the day of that council vote Related's attorneys e-mailed a "Community Benefits Agreement" to community representatives. It provides few real benefit and so far the record on actual delivery of the promised benefits has been sketchy.

Labor Gets on Board

Community Benefits Agreements in Los Angeles and elsewhere have been successful. In New York, though, developers routinely use such agreements as cover for bad projects. In 2005, mindful of both scenarios -- and knowing that securing a seat at the table provided no assurance that the community would be served anything but crumbs -- 19 organizations founded KARA. They included the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition, local housing and community organizations, and, in a departure from the standard community-vs.-developer playbook, labor with Service Employees International Union Local 32BJ, which represents porters, doormen and other property service workers; the NYC Building Trades; and the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union.

KARA’s platform demanded that the armory’s redevelopment prioritize uses that would serve the community, including schools. It also called for union construction jobs with local hiring and apprenticeships, and insisted that permanent retail jobs in the completed project pay a living wage – defined by KARA as $10 per hour plus benefits.

KARA hoped that employees of the armory’s tenants would end up carrying union cards. Like other industries, retail has seen the unionized share of its workforce shrink dramatically since the mid-20th century. Most retailers today pay poverty wages; they often employ immigrants who are most vulnerable to exploitation.

For its part, the retail workers union had worked with community organizations before, joining with Make the Road by Walking in Bushwick and working with GOLES (Good Old Lower Eastside) to create the Retail Action Project in SoHo in support of workers fighting against wage theft and other abuses.

Before the decline of organized labor in the U.S., unions were a part of the social fabric. If unions are to grow -- or even survive -- in the new economy, they need to rebuild their links to communities, according to Jeff Eichler, the retail workers' representative to KARA. Forming alliances and supporting low-wage, non-unionized workers in communities like the Northwest Bronx are very much in the unions’ self-interest, Eichler said.

KARA forged an alliance that could level the playing field with Related -- even when it became clear that city government, which should have been wearing referee’s stripes, was unapologetically playing for the developer’s team. As City Environmental Quality Review and ULURP mandated reviews rolled on, KARA examined reams of documents, bringing in experts in planning, finance, and traffic. "We did our research and kept the politicians up to speed," said Ava Farkas, lead organizer for the armory campaign since 2005.

KARA invited elected officials to reaffirm their support for the alliance and its principles. More than 1,000 community members turned out at an October 2009 meeting to hear Borough President RubĂ©n DĂaz Jr. call the fight for living wages in the armory a battle in "our new civil rights movement." Six weeks earlier, DĂaz had gone off the standard ULURP script and sent a negative recommendation to the City Planning Commission, citing the armory project's devastating traffic impacts and effects on existing local retailers. He also criticized Related's refusal to commit to a living wage requirement or negotiate a binding community benefits agreement with KARA.

City Planning approved the project, despite its seeming deviation from PlaNYC’s sustainability principles (for example, generating 14,600 new car trips per day). Planning sent the project on to the City Council for committee hearings in November and to its historic rejection by the full council on December 9.

The Next Steps

Even as KARA and its allies celebrated (and as the Real Estate Board of New York threatened retribution), members voiced their frustration at having been able to block a bad project, but unable to transform it into a good one. They didn't lack of a vision of their own -- though in hindsight, Farkas and others wondered whether the community caved too quickly on letting retail dominate the armory mix. But the City Charter provides only the flimsiest tools -- 197a plans -- for proactive community planning. Instead, the land use process puts developers and mayoral agencies in the driver's seat, and leaves communities, community boards and the City Council strapped firmly into the back seat. Will any effort at charter revision open an opportunity to change this dynamic?

KARA clearly succeeded in putting living wages on the table – for city-subsidized projects, at least. Bronx members Annabel Palma and Oliver Koppel have introduced a living wage bill into the City Council. It’s unclear whether state legislation also would also be needed. But the momentum is there, maybe even enough to move a bill through Albany. Retail and other low-wage sectors are growing much faster than better paying sectors; if New York is going to accept -- and even subsidize that -- isn’t it in the public interest to make sure that families can survive on what those jobs pay?

A recent analysis by the Center for an Urban Future validates KARA's assertion that the Bronx already has more than its share of low-wage jobs; 42 percent of Bronx workers over age 18 earn less than $11.54 an hour. A mandate applying to all city-funded projects would eliminate the coercive choice between bad jobs and no jobs that developers keep offering to communities like the northwest Bronx.

The alliance between community and labor on the living wage issue provided a novel twist in the armory story -- even though the service employees and the building trades both peeled off to endorse the mall just before the council vote. Will those unions eventually broaden their definition of self-interest in the way that the retails workers seem to be doing?

Bronx communities have repeatedly been rolled by mega-development projects – the Croton Filtration Plant, Yankee Stadium and the Gateway Mall -- that have promised training and apprenticeships, then largely failed to deliver. A community that can mobilize effectively enough to get a "no" vote on such projects from its elected officials could be a formidable adversary -- or a powerful ally -- to a labor movement that may find itself in need of friends as the new green economy takes shape.

And what about Kingsbridge Armory? KARA is ready to go back to the drawing board, with an even clearer understanding of what the Bronx stands to lose, and to gain. Realizing the damage that a mega-mall would inevitably inflict, KARA and its allies are seeking a community-led vision that will maximize local benefits without destroying the neighborhood.

They won’t have to look far for a precedent. Another armory opened its doors to its host community this month, gracefully accommodating a women’s shelter, community space and a YMCA whose gym will also serve local kids during the school day. The redevelopment of Brooklyn’s Park Slope Armory took years to move from vision to reality, but KARA members are already asking "why not here?"

Joan Byron leads the Sustainability and Environmental Justice Initiative at the Pratt Center for Community and Environmental Development. Byron and the Pratt Center worked with the North West Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition, and the Kingsbridge Armory Redevelopment Alliance, during the Kingsbridge Armory campaign.

Sour Holiday

Holiday cheer seemed to echo across the country Friday when the U.S. Census Bureau announced retail sales had increased 1.3 percent in November compared to the previous month.

Strike up the carols, it seems like the holiday season has arrived.

But here in New York, storeowners are not celebrating so quickly. From Jamaica, Queens to Melrose in the Bronx, storeowners say they have yet to see eggnog-fueled shoppers, craving holiday deals and discounts.

Small business owners compare their customers to characters in a Charles Dickens novel -- invoking the image of Scrooge rather than Santa.

Shoppers aren't aggressively embracing merriness either.

Gloria Anderson, a resident of the South Bronx for "forever" and a great-grandmother, isn't buying presents for her adult children. While perusing nightlights at Youngland in the Bronx, Anderson said she is focusing solely on her three great-grandchildren and four grandchildren.

"I'm trying to," said Anderson when asked if she was cutting back. "I'm only buying for the children."

Because of this frugality, storeowners throughout the city are bracing for a bad holiday season that might force some of them to close their doors.

But maybe the city can do something to help?

Mayor Michael Bloomberg has made it a hallmark of his tenure at City Hall to try to create commercial hubs in every borough -- like in Jamaica and the South Bronx.

Gotham Gazette visited several of these commercial strips to see how small businesses and shoppers were holding up this holiday season. We asked what they think should be done to bring them holiday cheer. See our slideshow, Sour Holiday to find out what they said.