A Community Plan for the 'Highway to Nowhere'

For 10 years, South Bronx residents have been fighting to get the state to tear down an old expressway so that a greener and more sustainable mixed-use neighborhood can take its place. The community's vision fits nicely with the goals of the city's long-term sustainability plan, PlaNYC2030. But will the city embrace this precocious community-based effort?

The Highway to Nowhere

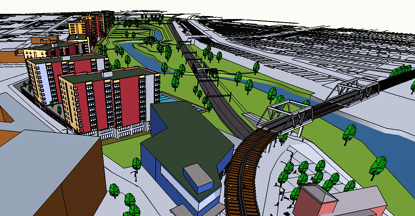

South Bronx residents have fought for a decade to cast off the shadow of Robert Moses' Sheridan expressway -- a 1.25-mile, little-used stretch of highway locally known as "the highway to nowhere." In its place they aim to build more than 1,000 sustainable and affordable apartments, greenways, parks, resident services and progressive businesses that will offer living-wage, long-term jobs to Bronx residents in the city's burgeoning "green industry" to Bronx residents.

One of Moses' few projects that never reached full fruition, the Sheridan Expressway carries an average of 37,000 cars a day (to compare, on any given day, approximately five times as many cars traverse the nearby Cross Bronx Expressway). Construction on the Sheridan began in 1958, and Moses named the road for his good friend, the Bronx commissioner of public works, Arthur V. Sheridan, who died in a car accident in 1952. Determined to provide yet another option for drivers traveling between New York City and New England, Moses originally envisioned the Sheridan to continue four miles north from the Cross Bronx Expressway through the New York Botanical Gardens and the Bronx Zoo, to the New England Thruway. In one of the first of several defeats that eventually ended Moses' reign, advocates for the gardens and the zoo blocked his plan. This was good news for the city, but the South Bronx was left with the redundant stub of an expressway that connects the Cross Bronx to the Bruckner -- a purpose already served by parallel stretches of the Major Deegan Expressway and the Bronx River Parkways.

Stunted or not, South Bronx residents say that the road does its share of damage. Not only does it cut them off from access to the Bronx River, but the Sheridan also separates Bronx Community Districts 2, 3 and 9 from one another. Home mostly to African American and Latino families with significantly lower than average household incomes, these districts also suffer from some of the highest asthma rates in the entire state. The traffic that trickles down the Sheridan exacerbates those asthma rates by adding to area air pollution. In addition, runoff from the highway "contribut[es] to combined sewage overflows during heavy rains, making local waterways (including the Bronx River) unsafe for recreation," said Philip Silva, coordinator for the Southern Bronx River Watershed Alliance, the group that is spearheading the effort to reclaim the highway.

Silva underscored the degree to which the highway foils hard-won community efforts to green the Bronx. For example, the Sheridan runs directly along the emerging Bronx River Greenway, a 23-mile multi-use path along the river that will ultimately connect the Bronx and Westchester. Fifteen miles of this project already are in place, including one of the project's centerpieces, a lush, 2.7-acre park along the western shore of the Bronx River. But getting across the Sheridan to reach the park can be hazardous. Only three or four pedestrian bridges provide access to the greenway and the river. "As it stands now, young kids jump over the guardrails and run across the highway to get to the river," Silva said. "Once this world class park is finished, you'll have even more demand for quicker access to the river and a lot more incidents of people putting themselves in danger."

The State's Plan

In 1998, the New York State Department of Transportation unveiled a proposal. to extend the Sheridan south onto Edgewater Road in Hunts Point. The plan calls for constructing a massive system of ramps next to the Bronx River and above one of the greenway's new parks in order to create a multilevel interchange between the Sheridan and the Bruckner Expressway.

Approximately 11,000 trucks a day currently travel through local streets on their way to and from the Hunt's Point Market. For years Hunt's Point residents have raised alarms about the health and safety hazards posed by the truck traffic. The state's proposal attempts to address one of the main sources of local asthma by connecting the Sheridan directly to the Hunt's Point Market and so diverting trucks from local streets. Despite that, community members claim that it is grossly inadequate in addressing their concerns. First, the plan mainly serves supply trucks arriving from the north; however, the bulk of trucks using the market are those of buyers who travel to and from the south -- those trucks would still have to use local streets. Second, the plan directs a steady current of trucks across the only pedestrian and bike route to one of the new greenway's parks.

The Community Vision

Almost immediately upon hearing about the expansion plan, Bronx community leaders rallied and then formed the watershed alliance, a coalition of five local and two citywide organizations, to imagine the possibilities for a highway-less neighborhood. "From there it snowballed to thinking about taking down the highway entirely," Silva said.

At a series of workshops in 2006, local residents, formal and informal neighborhood leaders, and experts from the Pratt Institute and the Tri-state Transportation Campaign, generated a new plan. It accommodates a larger volume of traffic through a number of on/off ramps from the Bruckner Expressway that will "swoop right into the market" while circumventing Hunt's Point neighborhoods. At the workshops, community members also made clear their desire for affordable housing, park land and employment in sustainable industries, all of which they included in the final version of what the community plan. Silva said that the community proposal is feasible since the state already owns the land, thus saving millions of dollars in acquisition costs and making the project more appealing to investors.

The state is presently completing its Environmental Impact Statement, which will evaluate the relative merits of the original expansion plan, the community plan and staying with the status quo. Because the state ultimately decides the Sheridan's fate, the alliance has focused most of its lobbying efforts there and has not yet officially presented its plan to city officials.

At the same time, Silva emphasized that city endorsement could have a significant influence on the state. Accordingly the alliance is now working to bring city and state officials together to take a holistic look at the project and ensure that traffic engineers don't get to make what is actually a far-reaching land use decision for the city.

For Silva and his colleagues, PlaNYC2030's release comes at a perfect time. "Our plan is a great demonstration of PlaNYC's principles," he said "It uses the highway footprint to create density without displacement, it connects the surrounding communities and our proposed new housing to the Bronx River and the Greenway, and at the same time addresses the issue of truck access to the industrial areas of Hunts Point."

Indeed, it seems as though "the stars are aligned" for a long-awaited marriage between the community plan for the Sheridan and Bloomberg's plan. The question is whether the city will recognize the obvious and commit to making it happen. As Silva said, the alliance "has been promoting sustainable urban development for 10 years and we're glad [the city] has shown up to the party." Now New Yorkers wait to see whether city officials will put on their hats and eat some cake.

Melissa Checker is assistant professor of urban studies at Queens College, City University of New York. She is the author of Polluted Promises: Environmental Racism and the Search for Justice in a Southern Town,Â

Without Major Action, Housing Crunch Will Only Get Worse

After five years of reporting and writing about housing issues, I decided to take a break. I have taken a new post in Ghana, West Africa, a region of the world I am familiar with from my days as a Peace Corps volunteer. Within a week of moving, I learned enough to know that housing issues are a hot topic here, too. I already heard one story about an eviction, and a Ghanaian told me that Accra, the capital city where I now live, has something akin to rent regulation. And grousing about landlords appears to be universal.

But back to New York, where housing issues have their own distinct flavor -- an increasingly bitter one for more and more people. As a friend told me recently, the city's "housing problems are not going anywhere soon. In fact, they'll probably get worse."

She was referring to a variety of indicators: Homelessness is as bad as ever. Virtually every type of affordable housing, from rent regulated apartments to middle income Mitchell-Lama apartments to public housing, is either disappearing or under severe stress. New Yorkers spend more of their incomes on rent than before. And the city's housing market, which had seemed impervious to the sub-prime crisis that is hitting many areas of the country hard, is showing signs of slowing down.

The housing "beast" is sick and getting sicker. Barring any interventions, low and moderate-income New Yorkers will suffer the most, but it looks like a lot of people are suffering and more will join them.

The challenges call for changes in the city, state and federal government's approach to housing, advocates argue. They have had success at the city level in recent months -- in April the City Council passed new laws that make it illegal to harass tenants and to refuse to rent to people because of their source of income.

Now, they are looking to the state for change, which had come, in modest doses, from former Gov. Eliot Spitzer. If the Democrats win control of the State Senate in November, much more could be done, advocates believe.

Many would hope to start with the Rent Guidelines Board, the nine-person panel composed of two landlord representatives, two tenant representatives and five public members, all appointed by the mayor. The board has set a range for increases this year, which could mean the biggest increases in rents in several years.

Such a move would hardly surprise advocates. Every year the board votes to increase rents, apparently deciding that the increase in the costs of operating buildings outweighs the economic difficulties faced by tenants. Just as the board's reports show that the costs of operating a building have increased, other studies show that rent burdens for New Yorkers have only increased.

The mayor's appointments to the board are one reason for this bias, advocates said. New legislation proposed at the state level would require the City Council to confirm the mayor's appointments.

But advocates are hardly giving up on the current board, said Kenny Schaeffer of the Met Council on Housing. "Some of the public members seem to understand that their job is not about rents," he said. "They see that it's about affordable housing."

Increases in the city's water and sewer rates and the costs of fuel are making many landlords anxious, said Mitch Posilkin of the Rent Stabilization Association, a trade group that represents the interests of over 25,000 landlords in the city.

"This particular round of rent guidelines increases is extraordinarily important," Posilkin said. "Smaller property owners are confronting the choice of paying their bills -- bills that cannot be deferred -- or maintaining their buildings."

Rent is just one measure of housing to look at, but it skews the conversation about housing toward the idea that it's all about money. It is not. Housing is fundamental, a human right. Let me pontificate briefly: Viewing it as a commodity cheapens its value terrifically. If we scratch at the surface of housing we see so many, more valuable issues: community stability; thriving families; physical, mental and spiritual health; and economic success.

Since I started writing about housing, one thing has been made clear to me: Unless and until elected representatives deal more seriously with the problems in housing, the city's housing problems will only intensify. The prospects that it will do that are unclear. Free market ideology is dominant -- hell, the city is going so far as to pay kids to go to school. Can politicians resist this and stand up to the market -- and its rich proponents in the real estate industry? New Yorkers might find out if the Democrats take control of the State Senate in November, but right now it's unlikely a party shift will bring about such a dramatic change in thinking.

Property owners, however, see the potential Democratic takeover as a threat, particularly if a newly Democratic Senate were to repeal the 1972 law, often referred to as the Urstadt Law, that effectively revoked the city's control over its housing laws.

"I think the recent actions by the City Council in passing the Section 8 legislation and the tenant harassment legislation are excellent indicators of how irresponsible the council would be if the city ever obtained jurisdiction over the rent regulation system as they seem to want to do," Posilkin said. "The council's stated intentions of seeing the Urstadt Law repealed are really frightening in light of the fact that the council does not seem to understand its role in developing proper and well-balanced legislation."

Advocates, though, see a major change in thinking as essential. "Without serious legislative changes, and with the population continuing to rise, the homeless population will increase and the fabric of the five boroughs will completely change," Rob Robinson, a housing organizer with Picture the Homeless, wrote in an email. "You'll be unable to live in NYC if you make under $100,000."

To be sure, there is a balance. Property owners' interests must be considered, but in many respects, the city and state have catered to the owners for well over a decade, recent changes notwithstanding.

Interesting times are ahead, to be sure, for housing. The problems are difficult and require serious attention. New Yorkers are not naĂŻve nor inexperienced when it comes to facing stiff challenges. So, despite the problems, the prospects that people will find adequate solutions are actually quite good.

I wouldn't know where to start if I began to thank people for making writing for the Gazette such a pleasure. You know who you are and your knowledge and insights on housing and on writing have made writing the column not only easy but quite pleasurable. I am eternally in your debt.

Joe Lamport was the former assistant director of the City-Wide Task Force on Housing Court, a coalition of community housing organizations.

The Blending of Church and Real Estate

In the very different Greenwich Village of the 1960s, Washington Square Methodist Church was so active in the anti-Vietnam War movement that it earned the moniker the "peace church." Forty years later the building remains, providing a place for New Yorkers to "come to be reborn."

Not in a religious sense, however. Now it serves as a "private refuge" offering original stained glass, Italian white marble countertops and quartz and slate floors for those who can afford to pay upward of $3 million for one of its eight apartments.

If the church's role in the 1960s was emblematic of the times, so, some might say, is its function today. Many city churches, particularly in Manhattan, no longer offer sermons, choirs or Sunday schools. Instead, they serve as places of profit, enjoyment and in some cases even sin, a shift that can have major effect on their communities.

The High Cost of Worship

The conversion of many houses of worship springs from two trends: a decline in religious membership in parts of the city and the value of property here.

Recent figures indicate that over 80 percent of New Yorkers consider themselves as affiliated with a faith. That does not mean, though, that they attended services.

Over the past century, attendance at religious services in the city has dropped, especially in Manhattan. Demographic shifts from neighborhood to neighborhood have affected attendance at churches, synagogues, mosques and temples. In response, Cardinal Edward Egan of the New York Archdiocese announced a "realignment" plan that has shut down or "merged" some of the city's Catholic parishes. The Catholic Church has some particular problems -- for one, its funds have been depleted to settle lawsuits brought by victims of sex abuse. But the Catholic Church is not alone in its downsizing.

Many church and synagogue goers have left Manhattan to move to the outer boroughs and the suburbs. The Catholic Churches plan, for example, sees a need for more churches and people far beyond the city limits in Orange, Rockland and Putnam counties, as well as northern Westchester and Duchess counties.

Meanwhile Manhattan has become home to young single professionals who have a tendency to drop out of their congregations over time, said one Upper East Side pastor, the Rev. Kazimierz A. Kowalski of the Church of our Lady of Good Counsel. "Often times when people get wealthy, people get lazy. In biblical history, when people get fat, they forget where they got the fat from," Kowalski said.

Religious properties in New York, like everything here, tend to be expensive to maintain, a particular burden for churches that may be seeing their membership -- and financial support -- decline. At the same time, the real estate boom has made the churches and their land increasingly valuable -- if the property can be used for something other than prayer.

From Peace to Posh

Vacant churches, along with seemingly every other available space in Manhattan, frequently often become luxury apartments. For landmarked churches, the outer structure is maintained and the inside is gutted then polished to perfection. (Some churches have been turned into low-income housing, but this occurs more often in the outer boroughs.)

This is the case with Washington Square Methodist. In its space, FLAnk Architecture created Novare, featuring eight spacious, luxuriously appointed $3 million to $6 million apartments, six of them with original stained glass.

"All different kinds of buyers have looked at it. The stained glass in this church was not iconographic in any way. But it is for a particular type of buyer who is comfortable being a trailblazer," said the vice president of the Corcoran Group, Brian Babst, who is in charge of sales for the building.

The real estate developers of Horsford Poteat are formulating plans to convert several Harlem churches into apartments, maintaining worship space on the ground floors and building condos above it. A project manager from the company who requested anonymity since the deals have not been finalized said, "The church leaders approached us about trying to bring some revenue back." She said that in Harlem, where some blocks have several churches, many no longer have enough members to survive.

AFC Realty has already converted the former Harlem Gospel Temple Church at 2056 Fifth Avenue into 22 condos priced at from $645,000 to $1.575 million. About half have been claimed so far.

Dancing in the Aisles

Many churches use music in their services-- but not the kind heard in some of these buildings today. In perhaps the most dramatic shift in purpose, a handful of one-time churches have been converted into places to dance, drink and hookup.

The most notorious church-turned-nightclub was Chelsea's Limelight, which was owned by Peter Gatien, the "Club King" of the 1980s and '90s. The Limelight building was constructed in 1846 as the Episcopal Church of the Holy Communion. After 130 years, it was closed in an Episcopalian church merger. But because it was a landmark the building survived -- though its mission certainly shifted.

Gatien's club opened inside the Gothic stone walls in 1983. Several years later, though, Limelight (as well as Gatien's other clubs, including The Palladium and Tunnel) was targeted with drug dealing lawsuits as part of Mayor Rudolph Giuliani's "quality of life" improvement campaign. The club was repeatedly raided and shut down by the New York Police Department from 1995 through 1997.

Gatien was convicted of tax evasion in 1999 but acquitted of the charges that he had been involved in selling the drugs taken in his clubs in 1998. When reporters asked how would celebrate his vindication, he responded, apparently without irony, "Right now I'm just grateful to God. I want to go to church."

A few years later, new owners opened another club -- Avalon -- in the church. Hunk-O-Mania, the male strip revue, hosted weekly parties where people once took communion. Avalon closed in 2007 and the space is now vacant, although there have been rumors that it will soon be turned into a mini-mall.

Eating in the Pews

There are also church restaurants. At Providence on West 57th Street, few traces of the Manhattan Baptist Church remain. A sound system has been implanted in the organ, and chandeliers now cover the arched wood ceiling. Neon light blinks from a dance floor in one part of the building, and a bar fills the altar space.

Manhattan Baptist Church was shut down for budgetary reasons in the 1960s. Throughout the 1970s and '80s, the building was used by Media Sound Studios and musicians like Jimi Hendrix, John Lennon, Aerosmith, Billy Joel and The Rolling Stones recorded albums there. The building then housed Le Bar Bat, a popular nightspot, before Providence took over.

Battles for Survival

Many New Yorkers would see the changes at these churches as virtually inevitable. As manufacturing has declined, developers have converted old factories to museums, high tech offices and the Chelsea Market. Similarly, as church attendance has dropped, new uses must be found for houses of worship.

Given the role of churches in the lives of their members and their communities, though, some New Yorkers want to preserve them. The conflict has pitted houses of worship against preservationists in neighborhoods across the city. The preservationists argue that many churches, synagogues and mosques are historic and cultural treasures that must be kept for future generations. On the other side, religious leaders and congregations contend that historic preservation can pose significant hardships, costing money that should go toward advancing a religious mission and for charity.

One such dispute concerned St. Brigid's on the east end of Tompkins Square Park in the East Village. In the late 1990s, St. Brigid's staff discovered that the east wall of the aging building was moving in the eastern direction about a quarter of an inch each year. Egan deemed the structure unsafe for parishioners, and the church was closed in 2001. The archdiocese was originally going to repair it, then later it decided to demolish the building and lease the land.

The church remained, though, partially through the effort of the "Save St. Brigid" campaign. Its supporters noted the rich history of an institution created in the 1840s to serve New York's growing Irish Catholic community. The church's architecture reflects its origins. The arched ceiled, for example, is fashioned as an upside-down boat and was built by Irish people who immigrated here to escape the potato famine in the 1840s and then found work in East

The campaign sufferd a number of setbakcs in courts and at the Landmark Preservation Commission. Then on May 21, the archdiocese announced that St. Brigid's would not be razed after all. An anonymous contributor had donated $20 million. Half of that will go to restore the church, $8 million will aid St. Brigid's school and $2 million will, according to a statement from the archdiocese, provide an endowment for the parish "so that it might best meet the religious and spiritual needs of the people."

"This incredible gift not only enables us to preserve the traditions and spirit of St. Brigid’s founders, it also allows us to protect the traditions of religious freedom, family and community that are the very fabric of this neighborhood and others throughout the city," said Edwin Torres, a former St. Brigid's parishioner and the current chairman of Save St. Brigid.

While St. Brigid's has apparently been saved, the issues presented by the dispute remain. "It's a problem of the cost of maintaining the church versus the profitability of the land," said Torres, earlier this month.

The Catholic Church rarely sells off a building or a plot of land. Egan generally prefers to hold on to the property to use it for parochial schools or charity offices, according to the spokesman for the archdiocese, Joseph Zwilling. However, exceptions do exist.

One is St. Ann's Church, several blocks away from St. Brigid's on East 12th Street. It had not been an active Catholic church for 30 years when the archdiocese put it on the market and sold it to the Hudson Companies developers who designed a dormitory for New York University. The builder knocked down all the church except for the facade (an effort to appease its neighbors), which stands in front of the 26-story brick building. This new structure is now the highest building in the East Village and has met with persistent protests in the community.

Divide and Save?

In their efforts to survive, many churches have made compromises, selling pieces of property to make money to fund other operations. The Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine in Morningside Heights is a prime example. The Episcopal cathedral had been in a financial crisis for most of its life, ever since its planning began in 1873. In the past few years, the cathedral has announced several "real estate initiatives," parceling off pieces of the 11.3 acres surrounding the church- to developers.

After working with the city Landmarks Preservation Commission, the cathedral signed an deal with Columbia University that would enable Columbia to build an academic facility on the north side of the cathedral close. So far, no precise plans have been announced.

On the southeast side, the cathedral granted a 99-year lease to AvalonBay developers to build a modern, glassy 20-story apartment building. One fifth of the apartments will affordable housing that the cathedral will help fund.

"The real estate initiatives were designed to not only pay for the deferred maintenance of the building, but to support the cathedral's programs, which include a homeless shelter, an emergency food pantry, arts program that funds free concerts and performances, and day care and after school programs," Jonathan Korzen, the cathedral's communications manager said.

A Hole in the Social Fabric

Like St. John the Divine, many houses of worship provide an array of service in a community. Beyond their core function as places of worship, they offer social and educational programs and provide meeting spaces for community groups.

As churches close, "some of our meetings have had to change locations," said an Alcoholics Anonymous volunteer coordinator in the New York Intergroup office in Chelsea. "In this neighborhood, we are worried about St. Vincent de Paul closing especially because it has a homeless shelter underneath it." She also noted that many of the churches are raising the rents they charge groups that use their space and forcing them to buy liability insurance.

The Food Bank of New York City has lost one of its soup kitchens, which used to operate out of Mary Help of Christians in the East Village before it was shut down in the Catholic Church's realignment. It is uncertain at this point what will take the 110-year-old church's place.

"It's awful what's happening right now with the use of church property," said Edwin Torres. "Our heritage, our history, our past need to be considered and should be preserved."

To say nothing of all those basements with coffee urns and free food.

Â