Giving Children Something to Live For

Kids at school (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Positioning efforts to alleviate childhood poverty in any way against efforts to build future assets for children is a mistake. I am a professor at the University of Michigan. As a child I grew up poor, evicted often, living in hotels, homeless at other times, while eating seemed optional, not mandatory, for survival in our house. I ended up dropping out of high school as many kids like me do.

Being poor in America is hard, I would not downplay that for a second. But the hardest thing I found about being poor is feeling like you have no tangible hope. This is not to say poor people don’t have hope, they do. For example, my mother and I would walk through affluent neighborhoods and talk of living there one day, but we could see no tangible way to make that dream a reality. While this type of hope helps you make it through the day, it doesn’t change how you behave. It is hope divorced from a future.

What has made the United States of America a destination, and the thing that makes it great, is not that you will not experience hardship, but in the midst of hardship you can see a way to a better future. In fact, when many people set out for the U.S., they understand that they will have to suffer untold risks and hardships. However, these risks and hardships pale in comparison to the concrete possibility of a better future. And while it might be vogue to downplay the importance of The American Dream nowadays, it is our belief in this dream that has carried us through our toughest times as a people.

This is not a dream about making it through the day, it is a promise that we can have a better tomorrow, that the land is rich and the institutions robust (even though access has not been equal), so if you work hard and have the ability you can change your position in life.

This is not an argument to abandon policies that give people “enough to live by,” indeed those are also needed. Instead, I am arguing that the drive Americans have demonstrated throughout history comes from more than having enough money to pay the bills each week, it comes from the promise of a better future. Not just yours, but that your children can have a better future. This promise feels tangible to us, because we see the richness of our land and the strength of our institutions.

When talking about the New Deal, Roosevelt put it this way: “Liberty requires opportunity to make a living decent according to the standard of the time, a living that gives man not only enough to live by, but something to live for.” Without this opportunity, he continued, “life was no longer free; liberty no longer real; men could no longer follow the pursuit of happiness.”

We must recognize the importance of building future assets for children, helping spark their power to pursue or maybe even dream of happiness.

Children’s Savings Account (CSAs) programs like what New York City and Mayor de Blasio have called ‘baby bonds’ are asset-building efforts, even if it can be argued that they do not go far enough. Assets allow and prompt children to plan for their futures. When children have assets of their own, they can begin to visualize their future selves going to college, buying a home, starting a business, or retiring one day. Hope becomes tangible, and not just wishful. Nurturing our children’s future selves is as important to motivating them to invest in the American way of life as meeting their daily needs. Dreams buoyed by well-funded CSAs allow a child to withstand hardship whether it be poverty, war, or even a pandemic.

Giving children a CSA (i.e., assets) is not delaying gratification but providing them with the capacity to think and plan for their futures, as American as apple pie or the iPhone.

****

William Elliott III is a Professor, Director of Joint Program in Social Work and Social Science, and Director of the Center on Assets, Education, and Inclusion (AEDI) at the University of Michigan.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Make No Mistake, the Ongoing Congestion Pricing Delay is Environmental Racism

Subway tunnels (photo: Governor's Office)

How many of our city's children need to suffer while the MTA conducts a 16-month ‘environmental review’ to implement congestion pricing in New York City?

Throughout 2020 and into this year, our city and state elected officials proclaimed in the face of COVID-19 and racial justice protests that they were ready to tackle the problematic issues generations of New Yorkers experienced—among them, solving the structural inequities caused by environmental racism and the harm that it does to our kids.

Back in 2019, the Union of Concerned Scientists concluded that the highways New York historically placed near communities of color "exacerbate lung and heart ailments, cause asthma attacks, and lead to both increased hospitalizations and mortality from cardiovascular diseases." Having housing near highways and disinvestments in public transportation worsened exposure to pollutants in these communities.

A deeply regrettable outcome of these decisions made our communities of color more susceptible to respiratory illnesses, like COVID-19, where well over 4,000 of our city's children lost a parent due to the pandemic (according to a study of the first wave, in 2020). And to the surprise of no one, that initial data showed one in 600 Black children and one in 700 Hispanic children lost parents due to COVID, double the rate compared to one in 1,500 white families. Another statistical example of the human consequences of our society's enduring prejudices.

The long-term effects of losing a parent will be hard to overcome. Children who experience parental loss at a young age battle early and persistent negative impacts on every aspect of their lives that stunt their social and emotional development. Among them, dealing with early-onset depression that continues throughout the person's lifetime.

And that's not all. Pollution continues harming their ability to learn and thrive, while making kids more susceptible to the next pandemic, or even more ‘regular’ illnesses, like the seasonal flu.

The Inter-American Development Bank conducted a study of 3,880 schools near pollutant-heavy areas and found that air pollution increased morbidity and mortality among children. Another study of schoolchildren by the Brookings Institute further validated those findings showing persistent exposure to air pollution increased fatigue, absenteeism, attention problems, poor test scores, and higher suspension rates.

It doesn't have to be this way.

Congestion pricing — set to be implemented in Manhattan south of 61st Street but impacting the entire city — will reduce car traffic, improve air quality, and help limit traffic crashes while increasing investments and access to our mass transportation system for the betterment of all New Yorkers.

There is no time to wait, and a 16-month review process is simply unacceptable. New York leaders must take action now to reduce that timeframe and get congestion pricing implemented as soon as possible.

The issues highlighted so starkly during 2020 have not gone away, and no action has been taken that resolves them, or even addresses them in a truly systemic fashion to improve health outcomes for our kids. But, we can embrace solutions that are ready for implementation, and congestion pricing is one of them.

The impetus is now on our elected leaders to expedite this plan for this generation of New York City kids. And the next.

***

Denny Salas is a former candidate for City Council who advocates for increasing affordable housing, pedestrianizing New York City streets, and eliminating structural inequities. On Twitter: @realdennysalas.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

‘Vigilante’ Mayoral Candidate Narrative Obscures History of New York City Resident Patrols

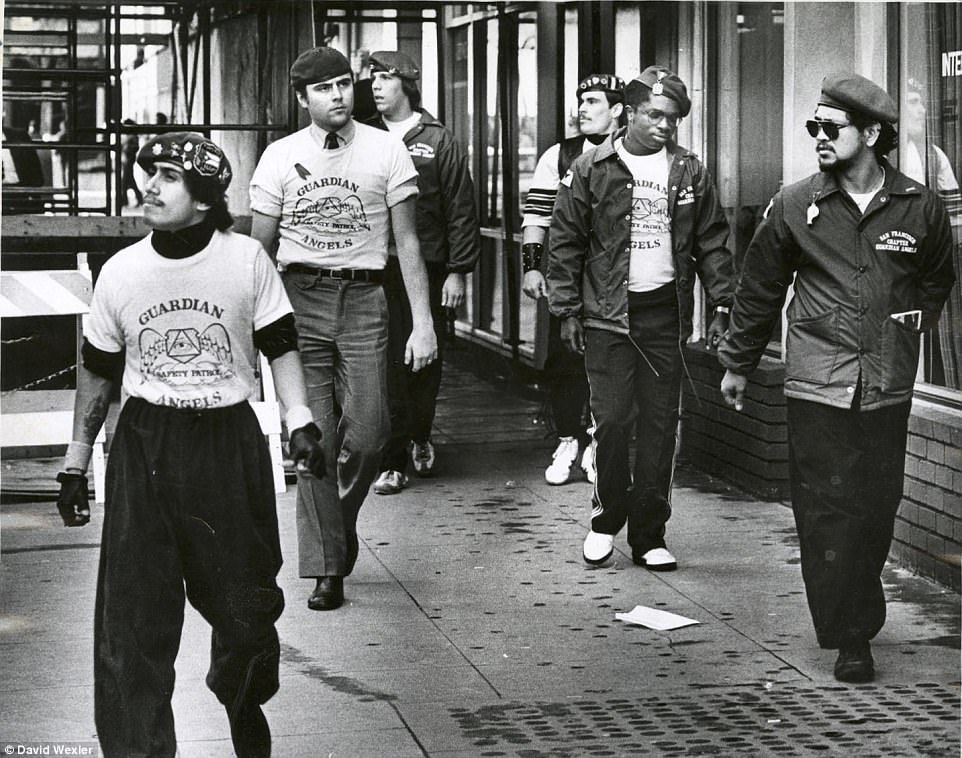

Curtis Sliwa & the Guardian Angels (photo: @CurtisSliwa)

Curtis Sliwa, the Republican nominee for New York City mayor, has portrayed himself as a police advocate and crimefighter dating back to his founding of the Guardian Angels in the late 1970s. But the image Sliwa has crafted of himself as the original civilian crimefighter distorts his role with the renegade patrol group.

While the Angels – a group of largely young African-American and Latino New Yorkers that began patrolling subways – may have been the most well-known volunteer crime-fighting group in the city – they were far from the first. They emerged only after wide swaths of New Yorkers pioneered a movement in which residents took to patrolling city streets. And it was Sliwa’s own deceitful tactics and bombastic deriding of law enforcement and officials while leading the Angels that helped facilitate the demise of this grassroots anti-crime movement that had been flourishing until that point.

In the mid-1960s, for example, Jewish residents of Crown Heights formed the Maccabees, the first citizen patrol of this time. Each night, hundreds of volunteers escorted residents and served as “crime-spotters” for the police in cars equipped with two-way radios.

Similar volunteer patrols grew in the years ahead. By the end of 1972, there were an estimated 15,000 volunteers in tenant and neighborhood patrols and at least 75 citizen car patrols.

New Yorkers formed these patrols out of deep concerns about rising crime. Homicides, for example, nearly tripled to 1,117 between 1960 and 1970. Many residents believed that the police – whether because they were outnumbered, inefficient, or just corrupt – were “not sufficient to check crime in our community,” as one group of Brooklyn residents put it.

For many whites, the city’s growing populations of color heightened fears about crime. But patrols also spread throughout African-American neighborhoods. In the early 1970s in Bedford-Stuyvesant, for example, 73 community groups came together to patrol residential areas, while Black shopkeepers formed their own patrol to stop holdups.

Citizen watches also spread throughout public housing projects, where by the end of the 1970s, nearly 13,000 residents patrolled across 127 developments. Residents of color commonly demanded not just more but better policing as well as greater educational and job opportunities that would address crime at its roots.

Though initially skeptical of these community patrols, officials ultimately switched course due to the city’s deteriorating economy. Officials supported these patrols as a low-cost means to combat crime as city budgets were constrained. In 1973, for example, Mayor John Lindsay initiated a program that provided matching funds for citizen patrols to purchase equipment like walkie-talkies and uniforms.

As the city’s financial conditions worsened over the 1970s, the police stepped up their support as well, especially through training programs. By late 1977, more than 32,000 residents had gone through the NYPD’s block watcher training while a Civilian Observation Patrol (COP) trained citizen patrols. By 1977, COP groups were active in nearly 65% of precincts.

Most critical to the growth of citizen patrols, however, was the thousands of residents who believed their volunteerism was necessary – from the residents who patrolled six nights a week in Hollis Hills to the dozens of community groups in the African-American areas of Crown Heights and Flatbush who patrolled on foot and by car in uniform with radios connected to the local precinct.

It was this environment – of a city gripped by widespread concerns about crime and by the belief that police alone could not stop it – that forged the opening for Sliwa and the Guardian Angels to move onto the subways and capture the attention of the city and the country. Indeed, by the time the Angels gained public prominence, volunteer anti-crime groups had become established across the city’s landscape. Citizen patrols numbered 60 in 1977 and 135 in 1982; the overall number of residents involved in anti-crime programs by that time doubled to 150,000.

Once the Angels emerged, Sliwa’s consistent criticism of the failures of officials and police to effectively address crime certainly had merit, but they were undermined by his arrogance and bravado as well as his self-promotion tactics, which were designed to keep himself in the media spotlight (a number of these schemes were faked, as Sliwa later admitted).

What’s more, Sliwa’s antics helped cause officials to become more cautious of supporting grassroots anti-crime initiatives. City officials dismissed the Angels as vigilantes, but also began pulling back on resources for resident patrols more generally, instead focusing more narrowly on boosting police funding. Over the 1980s, the number of residents involved in patrols ultimately declined by one third and the number of active block watchers dropped by over 80%.

Indeed, by many measures, Sliwa did more to help usher in the decline of the broader citizen patrol movement, rather than being the catalyst that he portrays himself to be.

Today, the city once again finds itself awash in concerns about public safety, despite crime rates remaining far lower than decades earlier and despite perceptive criticisms of police. And Sliwa’s position once again threatens community safety.

Sliwa’s campaign has expunged his criticisms of policing he once made from his biography while portraying him as having been the singular New Yorker who “had to do something” when all others had “resigned themselves to the reality” of crime to buttress his law and order credentials and call for increased police. This false narrative not only omits the richer and more complex history of citizen patrols in New York. It also deliberately diminishes proposed responses to crime that have emerged from within New York’s neighborhoods today that go beyond Sliwa’s position that the predominant path to safety lays with more police.

***

Benjamin Holtzman is an Assistant Professor of History at Lehman College and author of The Long Crisis: New York City and the Path to Neoliberalism. On Twitter @holtzman_b.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.