New Interstate Gas Pipeline Fuels Debate Over Safety And Fracking

This story is co-published by MetroFocus and Gotham Gazette.

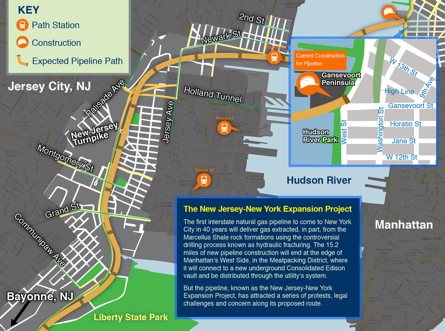

NEW YORK — The first interstate natural gas pipeline to come to New York City in 40 years will deliver gas extracted, in part, from the Marcellus Shale rock formations using the controversial drilling process known as hydraulic fracturing.

The 15.2 miles of new pipeline construction will end at the edge of Manhattan’s West Side, in the Meatpacking District, where it will connect to a new underground Consolidated Edison vault and be distributed through the utility’s system.

But the pipeline, known as the New Jersey-New York Expansion Project, has attracted a series of protests, legal challenges and concern along its proposed route.

Elected officials in Jersey City, including Mayor Jerramiah Healy, have opposed the pipeline on the basis that it would be built too closely to schools, parks and hospitals and could pose a public safety risk. Opponents of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, fear that increased natural gas use could encourage even more drilling. They also worry that high levels of radon gas will be carried by the pipeline to consumers. A series of last-ditch lawsuits are aiming to stop the project.

Spectra Energy Corp., which is building the pipeline, emphasized that it has nothing to do with the process of extracting gas.

Marylee Hanley, a spokeswoman for Spectra, compared the company to Fed Ex and added, "We simply are the transportation system and are governed by the regulations of the FERC [Federal Energy Regulatory Commission]. We move the gas along our system. (We are) an open-access pipeline. As long as any party has gas to be moved, we are required to move gas on our system."

Marylee Hanley, a spokeswoman for Spectra, compared the company to Fed Ex and added, "We simply are the transportation system and are governed by the regulations of the FERC [Federal Energy Regulatory Commission]. We move the gas along our system. (We are) an open-access pipeline. As long as any party has gas to be moved, we are required to move gas on our system."

When it goes online next year, the pipeline is expected to carry 800 million cubic feet of natural gas per day to the metropolitan area. Construction of the pipeline began in earnest this summer after Spectra, won approval from federal regulators in May to extend its Texas Eastern Transmission and Algonquin Gas Transmission pipelines.

Cleaner Fuel

The city is betting on the pipeline to help increase its capacity to meet the growing demand for the somewhat cheaper, cleaner fossil fuel.

In an op-ed published last month in The Washington Post, Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg and George Mitchell, a pioneer of hydraulic fracturing, responded to criticism of fracking, saying shale gas production through the method represents “the most significant development in the U.S. energy sector in generations.”

They wrote that not only was it “good for consumers’ pocketbooks” because it lowered the cost of energy, it also “helped stimulate major infrastructure investments” like the New Jersey-New York interstate pipeline.

Consolidated Edison said the Spectra project will provide huge benefits to its customers. "This project will enhance the reliability of our gas system, and help us meet a growing demand for natural gas," said spokesman Michael S. Clendenin in an emailed statement. "This project will also help improve air quality in New York City by allowing more consumers to convert their boilers from oil to natural gas."

The city passed regulations requiring buildings to stop using heavy heating oils and to replace them with an alternative — natural gas, No. 2 heating oil, biodiesel or steam. Buildings were required to begin the process of converting to a cleaner fuel beginning in July.

The city says converting buildings to cleaner fuels — including natural gas — could save hundreds of lives annually by reducing toxic air pollution caused by heavy heating oils.

The Spectra pipeline will deliver fuel for customers of both Consolidated Edison and National Grid, which service all five boroughs of New York City, as well as some parts of Westchester County. The pipeline will run through Linden, N.J., cut across the Arthur Kill strait into Staten Island, return to New Jersey, weave through Bayonne and Jersey City, and make its way across the Hudson River to Manhattan.

Map of the proposed project. Click to enlarge. Image courtesy MetroFocus/Kevon Greene.

It will then run through the Gansevoort Peninsula on the West Side and under the Hudson River Park before it connects with the Con Ed vault near 10th Avenue and Gansevoort Street, not far from where the Whitney Museum is constructing its new building.

Besides distributing gas from shale sources in Pennsylvania, the fuel will come from the Gulf Coast, Canada and the Rocky Mountains, the company says. Experts believe that production could shift over time to 90 percent of natural gas coming from extracting the fuel in the Marcellus and Utica Shales of Pennsylvania and New York.

Democratic Assemblywoman Deborah Glick, who represents the 66th district in Manhattan, which includes where the pipeline will enter the island, said she had received complaints about the project from a number of residents.

“Individuals want you to find a way to stop something they don't believe is good for the community, and many see the pipeline as bad,” she said.

But she said the growth of the city demands that new energy sources be brought online. “New neighborhoods [are] coming to the city and the population is growing, even along the west side,” she said, adding energy has to come from somewhere.

“The country is awash in natural gas, and not all is related to fracking,” she continued, but acknowledged that “clearly the fear is that this will be an avenue for more” fracking.

“The question,” she said, comes down to whether natural gas is going to provide fewer emissions than coal and oil, for example. “But you're polluting either way,” she said, noting that none of these are in fact “clean sources,” despite such language being used by those promoting the energy.

Environmental and Safety Concerns

In an environmental impact study on the proposed pipeline, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission found that the risks from the pipeline were “minimal.”

“The applicants have demonstrated their project is needed by their willingness to bear the risk that the project’s costs can be recovered without subsidization from existing customers,” FERC said in the study. “The fact that the entire capacity of the proposed NJ-NY Project is subscribed under precedent agreements with 15- to 20-year terms is strong evidence that the market also believes that the project is needed.”

But environmentalists say federal studies have failed to fully account for the dangers of the pipeline, noting in particular the large quantities of carcinogenic radon in Marcellus Shale, which some scientists contend will not fully decompose before it reaches the city.

Spectra said that radon exposure had been reviewed by FERC in its environmental impact study, saying the agency "refers to several studies, including studies by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy, that have concluded radon in natural gas does not pose a health or safety risk to the public.”

But some environmental groups are adamantly opposed to any pipelines that could lead to fracking.

"We have been, and are, opposed to the development of any new infrastructure — such as the pipeline — that facilitate the increased burning of natural gas,” said Frank Eadie, a representative of the New York Chapter of the Sierra Club, which is also considering litigation to stop the project.

While the project gained FERC support after a bruising two-year public relations battle in New Jersey, it is only recently that residents in Manhattan have decided to take legal action against the construction of the pipeline.

Earlier this month, six organizations sued to halt construction, filing an emergency petition in New York State Supreme Court, and calling for a temporary restraining order and injunctive relief against Spectra, Hudson River Park Trust and other groups.

The groups reached a compromise earlier this week over one of the main complaints — that the 24/7 construction at the Gansevoort Peninsula limited bike and pedestrian traffic at the Hudson River Park — after Spectra agreed to place a crossing guard to monitor the trucks entering and exiting the construction site, according to Jeff Zimmmerman, one of the attorneys who filed the original complaint.

He said they are still suing to halt construction, with a judge set to hear arguments in November.

In their lawsuit, along with environmental concerns, the organizations cited the risk of pipeline explosions, giving as an example the 2010 explosion in San Bruno, Calif., that killed eight people and caused millions in property damage.

Spectra says that, unlike the San Bruno pipeline, the New Jersey-New York Expansion Project will be stronger, thicker, buried deeper and will involve 100 percent x-ray inspection of welds.

"So, to compare our pipeline to that in the San Bruno incident is simply not correct," the company said in a presentation on the project it says was shown to Jersey City residents. "We have layers and layers of safety measures built into the design, construction and operation and maintenance."

In July, the U.S. Department of Transportation's Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration fined Spectra over $134,000 for safety violations in their pipelines in Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana and the Gulf of Mexico.

Spectra spokeswoman Hanley said the fines stemmed from “corrosion” to the pipelines, but insisted such damage would not be “life-threatening,” though she refrained from elaborating why. She did note that Texas Eastern Transmission, the parent company of Spectra, “will be reviewing policies and procedures and reviewing all of the findings” by the PHMSA.

Of the seven violations in total, three of the findings resulted in the $134,000 in civil penalties. These had to do with maintenance and inspection failings, as well as above-ground monitoring of the area.

The remaining four penalties "involved facility and right-of-way maintenance."

Spectra has long maintained the New Jersey-New York pipeline will be “among the safest in the nation,” pointing to changes in technology available to them, such as a 24-hour monitoring system. Those safeguards meet and often exceed the highest federal safety requirements, the company says.

All told, there have been 62 gas transmission explosions that have resulted in 34 deaths and almost $400 million in damage nationwide since 2000, according to the PHMSA.

The causes of the explosions ranged from external corrosion, damage from negligence, incorrect operation, equipment failure, and natural force, while the cause of a few pipeline explosions remain unknown. The images of the 150-foot flames from the San Bruno, California, explosion, are often highlighted by pipeline opponents when discussing safety.

Experts have also warned about the potential vulnerability of pipelines to terrorist attacks — one example being the foiled attempt to explode a jet fuel pipeline at John F. Kennedy International Airport in 2009.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security also issued an alert in May about cyber attacks on the control systems of various gas pipelines nationwide. In a DHS newsletter, the agency notes reports of "targeted attempts and intrusions into multiple natural gas pipeline sector organizations.”

____

Sarah Crean and Cristian Salazar contributed to this report. Image of Spectra pipeline being layed extracted from FERC weekly summary compliance report, dated Sept. 10-16, 2012.

NYC Bets on Natural Gas to Reduce Air Pollution

NEW YORK — Plumes of black smoke rippling from rooftops are a common sight along the city's skyline — and have long unsettled public health experts.

The city has called for replacing the heavy heating oils used in buildings that are mostly responsible for the toxic dark smoke with substantially cleaner fuels by 2030.

And while there are a handful of alternatives for building owners to choose from, policymakers expect that natural gas will be among the most attractive options because of its low cost and decreased emissions.

The city, in turn, has pushed to expand the capacity of infrastructure to handle natural gas through the construction of the first new pipelines in decades that will carry enough of the cleaner fossil fuel to power millions of buildings and households. But the construction of the pipelines has stoked the passions of residents along the paths where they will be built; environmentalists concerned about the impact of construction on delicate ecosystems; and opponents of hydraulic fracturing.

One of those projects got another boost Saturday when the U.S. Senate passed legislation that would allow the construction of a 3.17-mile natural gas pipeline and facilities going from the Atlantic Ocean off the Rockaways, through Jacob Riis Park and Gateway National Recreation Area.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg praised the passage of the New York City Natural Gas Supply Enhancement Act, saying it was "not just about the construction and operation of a natural gas pipeline and the jobs it will create."

"It is critical to building a stable, clean-energy future for New York City and improving the health of all New Yorkers," he said in a statement over the weekend.

Work on the New Jersey-New York Expansion Project, as the other project is called, began on Manhattan's West Side earlier this summer.

"The administration is supporting those projects because they're being done responsibly, they're being done safely, and with minimal environmental impacts. And they ultimately are going to have a huge public health benefit," said Deputy Mayor for Operations Cas Holloway, in an exclusive interview with Gotham Gazette last week.

Some statistics long cited by the city state that 6 percent of annual deaths in New York City are attributable to poor air quality from pollutants.

Holloway, who testified for the administration in support of the bill that passed in Congress, said the goal of the city's program to convert buildings to cleaner fuels — known as Clean Heat — is to "accelerate" the "public health benefit" of reduced air pollution. By the end of 2013, the city hopes to reach a 50 percent reduction of the nasty emissions attributed to the burning of heavy oils by buildings.

To get a better sense of what the city's energy plan will mean in the years ahead and why the two pipeline projects are expected to play such an important role, we spoke with key policymakers, environmentalists and residents.

Over the next week, we will be publishing stories on both pipeline projects and taking questions and comments on Facebook and Twitter.

The goal of modernizing and expanding the distribution of natural gas is one of hundreds of goals detailed under Bloomberg's PlanNYC, originally released in 2007 and in updated form in 2011. The far-reaching blueprint calls for the transformation of how the city deals with everything from housing and water supply to its waterfront and air quality, with the aim of making the city sustainable as it grows by about one million people and faces changes from climate change.

Under the plan, the goal for energy is to reduce consumption and make energy systems "cleaner and more reliable." Under the plan for energy, one initiative called for increasing "natural gas transmission and distribution capacity to improve reliability."

"City regulations eliminating the use of highly polluting residual heating oil will increase demand for new gas service. With gas prices nearing historic lows and expected to remain below oil prices for some time, building owners have the unique opportunity to upgrade their heating systems while generating a return on their investment," the updated plan states.

In April 2011, the city's Department of Environmental Protection issued regulations effectively requiring that buildings stop using No. 6 and No. 4 heavy heating oils, and replace them with an alternative — natural gas, No. 2 heating oil, biodiesel or steam. Buildings were required to begin the process of converting to a cleaner fuel beginning in July.

At the same time, the city also launched its Clean Heat program, saying that "just one percent of all buildings in the city produce 86 percent of the total soot pollution … more than all the cars and trucks in New York City combined" — by using heavy heating oils.

The city said the pollution from heavy heating oils contributed to the deaths of hundreds of people each year, and was one of the main contributors to high asthma rates among children.

In June 2012, the city announced $100 million in financing to help buildings convert to cleaner fuels.

Holloway said that "from the city's perspective," they were "agnostic" about which fuel is chosen, but "we think that natural gas will, ultimately, from an economic perspective, will be what more people choose."

The city is already a major consumer of natural gas, both to generate electricity and to heat homes and businesses. According to an ICF International study commissioned by the mayor's Office of Long-Term Planning and Sustainability, “Approximately 57 percent of NYC’s energy use is fueled by natural gas, either directly through on-site combustion to heat and cool buildings, or indirectly through the use of gas at power plants to generate electricity.”

Mark Brownstein, the chief counsel of the energy program at Environmental Defense Fund, said that "as a practical matter" natural gas "looks to be an attractive option."

But he said “the issue is not expanding the supply of natural gas. The issue is getting off #4 and #6 fuel oil."

(The EDF received a $6 million grant from Mayor Bloomberg's private foundation to examine how to strengthen the regulatory framework for hydraulic fracturing throughout the country and address public health concerns.)

Jackson Morris, senior policy analyst at the Pace Energy and Climate Center, said, "Every piece of the puzzle contributes to air quality."

“The fact that there are a ton of old buildings that are still burning #6 oil is medieval," he continued. "It’s inexcusable from a public health perspective … A lot of these boilers are at elementary schools. It’s the dirtiest oil money can buy."

Natural gas is not without its emissions. There is a debate in the scientific community regarding the full greenhouse gas impact of natural gas, relative to other fossil fuels like oil and coal.

The ICF study reports that all major studies except for one (by Cornell University) found that natural gas has significantly lower (36-47 percent) life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions than coal. The Cornell study attracted a lot of attention and, according to ICF, used newer data than what is currently used by the International Panel on Climate Change.

ICF projects that 88.5 percent of natural gas entering New York City by 2030 will come from sources in the Northeast, including from the Marcellus and Utica shales. The extraction process for shale gas, hydraulic fracturing, has attracted considerable attention because of concerns regarding air pollution, industrialization of rural communities and possible contamination of water supplies.

The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation is weighing whether to allow fracking. The agency announced Thursday that the State's Health Commissioner, Nirav Shah, will assess the DEC's analysis of public health impacts associated with hydraulic fracturing. The agency has already agreed to ban the process within the boundaries of New York City's upstate watershed, which supplies the city's drinking water.

Asked about whether there were any concerns about gas extracted through hydraulic fracturing in Pennsylvania being piped to New York City, Holloway said, "Any industrial process without the right safeguards is something to be concerned about. "

Ross Gould, the air and energy project director at Environmental Advocates of New York, said the focus should be on energy efficiency, not changing the city's reliance from "one fossil fuel to another" — natural gas.

“The question you should be asking is, what have been the barriers and obstacles to energy efficiency and renewables," he said. "What has held us back?”

Holloway said the city is working on projects to increase the production of renewable energy through solar, wind, hydroelectric and other technologies. But he said the process of getting that to market was time consuming, and there was still a lot to be worked out in terms of connecting those sources to the grid.

"We need to get there. What do you do in the mean time? Do you keep burning dirty fuels? No," Holloway said.

In the meantime, with the city breaking records each year for peak demand, he said natural gas was the likely energy bridge for the next few decades. "I think that that is just the reality of it," he said.

____

Photo of gas burner by Flickr user stevendepolo, used under Creative Commons license.

Council Wants City to Prepare for Extreme Weather of Climate Change

NEW YORK — For Sabrina Terry, the Sunset Park neighborhood where she works is at the front line of climate change.

The community along the Brooklyn waterfront is home to waste transfer stations, power plants, industrial facilities and tens of thousands of mostly low-wage immigrants. Devastating storm surges expected to be brought on by radically altered weather could flood the area and create a toxic brew.

“If you have a storm, who knows what is being washed up into the community? It’s not just the water — it’s what is being carried,” said Terry, an environmental justice planner who works for Uprose, a community-based organization.

Terry and her group have been vocal about their belief that the city wasn’t preparing sufficiently for the impact that climate change would have on coastal communities already struggling with environmental problems.

The City Council took steps to address those concerns yesterday, voting in favor of a bill that would enlarge the scope of a climate change panel and task force to focus on populations that are especially vulnerable to extreme weather events — such as the elderly, children and the poor. The legislation also makes the panel and task force permanent.

Council Speaker Christine Quinn said the point was to make sure that the city was thinking as broadly as possible.

“When you have severe weather circumstances and, say you need to evacuate people, it’s obviously more challenging at times to evacuate seniors, disabled New Yorkers,” she said in remarks to the press before their only full-council meeting in August. “If you don’t have a plan for that, it is going to be doubly hard.”

Councilman James Gennaro, who drafted the bill, said that when the city’s panel on climate change was created by Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s office in 2008, it was directed to focus its work on protecting critical infrastructure. “We feel it’s important to protect people, too,” he said.

The city launched PlaNYC in 2007, an ongoing sustainability planning effort involving 25 city agencies to prepare for population increase, strengthen the local economy and combat climate change. The city has also moved to reduce carbon emissions generated by government and by commercial and residential activity.

The mayor’s office was supportive of the council's measure. “It is building into law what we are doing,” said Bloomberg spokeswoman Lauren Passalacqua. “This is now a fixture of how the city thinks and operates.”

Terry praised the council for acknowledging the feedback from the environmental justice community. “In this new draft of the bill, they do acknowledge local leadership to ensure that this message gets out to the people who really need it,” she said.

Paul Gallay, president of Hudson Riverkeeper, called the legislation “groundbreaking.”

“This is an effort to get on top of the biggest challenge the city may face in coming years, and to be inclusive about it,” he said.

In remarks made at an environmental protection committee meeting Tuesday, Gennaro said that, if passed, it would be the first time a municipality in the U.S. had decided to codify climate change preparation measures within city law. That claim could not be verified by press time.

Maintaining and overseeing public health, natural systems such as wetlands and waterways, the city’s critical infrastructure and overall building stock, and the health of the local economy will be the focus of climate-change planning and adaptation efforts, according to the legislation.

The two bodies that the bill will make permanent, the New York City Panel on Climate Change and the Climate Change Adaptation Task Force, work together to forecast and plan for climate change within the five boroughs.

Gennaro explained that the adaptation task force functions as “the boots on the ground,” employing the analysis developed by the panel’s scientific experts. The task force will be responsible for planning and implementing “hard strategies,” such as a network of storm surge barriers; “green strategies,” including marsh restoration; and “soft strategies” — zoning, for example.

The task force is comprised mainly of relevant city agencies, but will also include public members "not limited to representatives from organizations in the health care, communications, energy and transportation fields,” according to the legislation.

In 2010, the panel — made up of climate scientists and academics, along with legal, insurance and risk management experts from the private sector appointed by the mayor — released what was described as the first official climate change projections for the city.

According to the report, the city’s vulnerability to progressive sea level rise and the flooding of low-lying neighborhoods and infrastructure is a key challenge. Intensified storms could also cause more inland flooding. At the same time, heat waves are likely to occur more frequently and for longer periods; severe droughts are also projected.

The bill codifies one part of a two-pillar strategy to tackle climate change. Earlier legislation dealt with how the city can reduce its carbon emissions.

If the legislation becomes law, both the panel and the task force will be required to meet at least twice a year. The panel is required to release new climate change projections within one year of the release of climate data by the U.N.’s intergovernmental panel on climate change, and once every three years at minimum. The task force is required to create an inventory of potential risks and identify issues for further study within one year of new projections.

All reports are to be made available to the public and both bodies are to coordinate with the mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning and Sustainability on developing borough and community-level communications strategies.

“It’s important to think reasonably about the impacts which are coming,” Gennaro said in an interview. “We are a coastal city.”

State Senator Calls for Gov to Meet with Fracking Critics

State. Sen. Tony Avella at an anti-fracking rally in June 2011. Photo by Adrian Kinloch, used under a Creative Commons license.

NEW YORK – State Sen. Tony Avella has called on Gov. Andrew Cuomo to meet with legislators, public health researchers and the director of the Oscar-nominated documentary “Gasland” to discuss the negative impacts of hydraulic fracturing.

"The gas and oil industry has already been readily engaged in the process of review and information sharing," he said in a letter sent to the governor yesterday. "It is now time to expand that review … to include numerous medical professionals, scientists and environmentalist[s] who have repeatedly stated their willingness to engage."

At a forum on Wednesday, Avella said he thought the governor and the state’s environmental regulatory agency are "moving rather quickly” on a decision to allow the controversial form of natural gas drilling - also known as fracking – in New York.

Avella’s challenge to Cuomo came during Wednesday’s hearing held by Democrats on the state’s environmental conservation committee in Manhattan, where dozens of opponents of fracking gathered to voice their concerns. They heard testimony from public health researchers, economists and natural gas experts.

The plan proposed by Cuomo and detailed in a Department of Environmental Conservation environmental impact statement would allow natural gas companies to drill within five southwest counties in upstate New York at the deepest core of the Marcellus shale rock formations.

In hydraulic fracturing sand, chemicals and water are injected to extract natural gas. The process has raised concerns over contamination of groundwater and the city’s watershed.

At the forum yesterday, Elaine Hill, a doctoral student from Cornell University studying the effects of unconventional natural gas development in Pennsylvania, Colorado and Texas claimed newborn babies within a close proximity to fracking wells could be subject to a significant decrease in birthweight.

Many anti-fracking environmental advocates and public health researchers present at the forum called for the DEC to accept an independent health and seismological assessment of the drilling process, saying the studies should be both peer-reviewed and separate from the natural gas company-funded studies.

Pepacton Institute economist Jannette M. Barth noted the ad-valorem tax, which measures gas value over time, may not start until 5 years of drilling – while surrounding communities incur immediate costs of production without any source of revenue.

Barth disputed a gas industry-funded study claiming 70,000 new jobs would be created through fracking in New York.

She said this will be “a boom and bust cycle” of short-term, out of state workers.

“They may work for two weeks at a time, while sending wages to home states helping those economies, but jobs are gone once the rig moves to another state,” Barth said

Attorney Elisabeth Radow noted that Nationwide Mutual Insurance Co., will not renew insurance on homes leased to fracking. She said with contamination of water and air quality “mortgages and home values would plummet.”

Chris Northrop, an oil and gas investor in Texas and New Mexico for 30 years, testified against the DEC being able to issue permits to natural gas companies and manage environmental requirements.

“There should be an autonomous environmental oversight,” he said.

In the forum Avella said this is a “conflict of interest” after Senate Democrats accused the DEC of sharing information with drilling companies months before the public got to see the process.

In a NY1 report, the governor was asked to comment on the issue at a public event in upstate Utica.

"They should be talking to the industry," he said. "They should be talking to supporters. They should be talking to opponents. They should be talking to people in Pennsylvania. They should be talking to everyone. This decision should not be made in secret," he said.

In January, Avella along with two other state senators, introduced legislation to regulate fracking. One measure called for banning fracking in New York, while another called for treating contaminated water under hazardous waste regulations if fracking were to be permitted.

“Since there’s a Republican majority, the bills didn’t go anywhere,” said Avella spokesman Xavier San Miguel.

Independent Oil and Gas Association of New York spokeswoman Cherie Messore noted that this new plan to start fracking has “huge economic benefits”

She said wells had already been successfully fractured. The governor’s plan would allow workers to “drill laterally into tight porous shale formations” that were previously “not accessible for the past ten or twelve years,” she said.

She defended the natural gas industry as being “established for 60 years” in the U.S. and having an “absolute stellar record” with “no dangerous groundwater contamination.”

Messore also said the technology practiced is proven and safe. Commenting on lateral hydraulic drilling, she said: “In other parts of the U.S., this is a standard practice.”

James Smith, another spokesman for the IOGANY, said Wednesday’s forum was “more of a rally than an educational session.” He did not attend.

Josh Fox, the director of “Gasland,” presented an emergency short film “The Sky is Pink” during the forum. He said that “over a thirty-year period half of all gas wells will fail” due to cement well case leakages, according to a study titled “Why Gas Wells Leak?” done by Schlumberger, the world’s largest oil services company.

But Smith said cement case leaks “happens naturally” and are not caused by drilling. He said that, in New York, seven layers of cement and steel well casings are made to protect fluid in the well pipes.

But he acknowledged that “the process isn’t foolproof” but added that there was a payoff for landowners who agree to drilling. He said they “will have wealth they never had before to keep their farms going.”

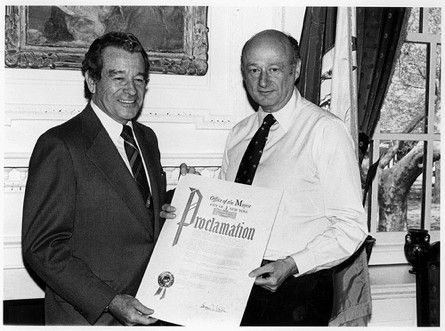

Koch, once courted by Indian Point operator to be pitchman, explains opposition to nuclear plant

Mayor Ed Koch at City Hall, date unknown. Photo from Flickr, courtesy Kheel Center, Cornell University.

Editor's Note: A previous version of this story incorrectly referred to the findings of a draft report based on data from the New York Independent System Operator.

NEW YORK – For former Mayor Ed Koch, the turning point in his thinking about nuclear power came in March 2011 after the radioactive cataclysm in Japan caused by a crushing tsunami.

“It was incredible how the Japanese government changed its warnings from day to day,” Koch said of the response to the multiple meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi plant that became the worst nuclear disaster since the 1986 explosion at Chernobyl.

“It was clear to me that the owners of the facility were lying. The Japanese government lied at times as well. I thought to myself, what's the sense of all of this? When I put all that together I said, the hell with it. I said, why are we tempting fate? Germany will eliminate all nuclear power, and that's what we should do,” Koch told the Gotham Gazette in a recent interview.

Koch has joined a growing chorus of environmental advocates and politicians calling for Indian Point Energy Center in Westchester County to be shut down, saying the aging nuclear plant poses a danger to the 8 million people who live 24 miles to the south in New York City – especially in the wake of what was learned from the Fukushima disaster.

“We know there is no possibility of evacuating New York City,” he said. “There is no evacuation plan.”

Koch said he had been aware of the problem when he was mayor, but did nothing about it. “I thought, â€It's not my problem. It's the governor's problem and the federal government's problem.’ I should have said it was my problem. I did nothing to address it at the time. I should have.”

Koch’s turnabout on nuclear power surprised some people, not the least of whom were officials at Entergy Corp., the owner of the Indian Point nuclear plant.

The company, which has applied to the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission to extend its operating license for another 20 years, said it had approached Koch two years ago asking him to be pitchman for its coolant system. Koch confirmed that he had been approached by the company.

“I said if I were to do it, they would have to provide scientific opinions that the alternative method was acceptable scientifically and would do the job, to which they agreed,” Koch told the Gazette in an email.

“At that time, I was in support of the use of nuclear energy. Fukushima had not yet occurred. However, after thinking about the offer, I turned it down because I thought it would have an adverse impact on my pro bono efforts to get support for the campaign to have the legislature accept impartial redistricting,” he continued, referring to his fight for an independent redistricting commission. “When I called to say I wouldn’t do it, I was offered $150,000. I said no, I wouldn’t do it no matter what the pay.”

Entergy, through a spokesman, denied they offered him money, instead saying it was the former mayor who brought up the subject of payment. Both Entergy and Koch confirmed, however, that the former mayor ultimately declined to promote the facility.

In a June 13 column in The Huffington Post, written with Hudson Riverkeeper president Paul Gallay, Koch noted that one of Indian Point’s two reactors faces the highest risk of damage due to an earthquake of any nuclear facility in the U.S.

The claim was first reported in 2011 by MSNBC after an analysis of NRC data -- but was later disputed by the agency itself. "Nuclear power is a complicated, technical subject, and we naturally try to simplify it to make it understandable to the general public. Sometimes, however, simplification leads to misunderstanding, and misunderstanding causes fear," wrote NRC spokesman Eliot Brenner on the agency's website. The NRC, he said, does not rank nuclear plants according to seismic risk.

Koch and Gallay also cited a 2008 study by scientists at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory that confirmed that Indian Point sits “astride the intersection” of two active seismic zones.

Koch and Gallay also point out in their article that the plant’s fire safety plan does not meet minimum federal standards.

Entergy disputes these claims. Indian Point spokesman Jim Steets said the analysis conducted by Lamont-Doherty “is not fact-based. They have expressed opinions. We are prepared to withstand an earthquake 100 times greater than what would have been experienced in the Indian Point area.”

But he also added: “There is some evidence that earthquakes (in the area) could be stronger. We are looking into that.”

Steets said the cooling system for the Daiichi plant’s reactors was damaged by the tsunami, not by the earthquake that preceded it. But the results of an independent investigation commissioned by the Japanese parliament say otherwise.

“A conclusion denying quake damage cannot be drawn,” said the report released last week. “The recorded seismic motion at Fukushima Daiichi exceeded the assumption of the new guideline. It is clear that appropriate anti-seismic reinforcements were not in place at the time of the March 11 earthquake.”

As for the plant’s fire plan, Steets replied: “The issue has been resolved to NRC’s satisfaction. A lot of the remedies have been completed; others are being engineered and resolved.”

But it is Entergy’s evacuation plan for the area around Indian Point, in the case of an accident, that particularly resonates with the former mayor. The company confirmed that the plant’s “emergency planning zone” encompasses the 10-mile area around Indian Point and makes no provision for New York City.

But Steets said the flooding that destroyed the Daiichi plant’s reactors was impossible at Indian Point’s location, and that the design of the plant negated the possibility of a massive explosion, such as the one at Chernobyl.

These factors would give the city time to mobilize in the event of an accident, he said. “An emergency that necessitated a massive evacuation would not occur instantaneously,” Steets said.

The city’s Office of Emergency Management has designed an “area evacuation plan” that could be used in the event of a nuclear accident, a spokeswoman said. The plan is currently designed to evacuate one neighborhood or swaths of the city in coordination with transit agencies.

But OEM spokeswoman Judith Kane said it could be used to evacuate the whole city “in theory,” though she said it was “hard to imagine” such a scenario. She said that in the case of a nuclear emergency, the city would likely rely on plume modeling to track the spread of radiation and make decisions.

The disaster in Fukushima, she said, encouraged the agency to coordinate more closely with its counterpart in Westchester County. “It's inevitable with any disaster,” she said. “When something happens in another part of the world, it always raises the question, what would happen in New York City? Is this good enough? Does it cover the worst case scenario?"

After the disaster in Fukushima, a 12-mile exclusion zone was established around the Daiichi plant and approximately 170,000 residents were evacuated. Persons living 12 to 24 miles from the plant were first asked to remain indoors, and then evacuations were initiated for these areas as well.

Koch said that if he were in the current mayor’s position he “would be putting the city’s experts together preparing a memo of opposition to the renewal application.”

Mayor Michael Bloomberg has spoken in favor of renewing Indian Point’s licenses, and has sharply rejected the idea of closing the plant.

“Well, if you closed Indian Point down today we’d have enormous blackouts. There is no alternative to the energy that we get from Indian Point. Four or five years from now that probably is not going to be true,” Bloomberg said in June 2011. “All types of power generation have risks and nuclear hasn’t killed anybody.”

In their article, Koch and Gallay said the New York metro area does not require Indian Point for its immediate power needs, arguing there is enough surplus power available to close the plant now and still meet regional demands through 2020.

A study commissioned by New York City confirmed that 2011 data from the New York Independent System Operator showed sufficient power through 2020.

But the final version of the report by Charles River Associates adjusted the ISO's forecast of 91 percent energy efficiency penetration – the degree to which energy efficiency targets have been met – saying that a 50 percent rate was more "realistic."

After adjusting the ISO data, the final report argued that the grid would fall short in the summer of 2016. Charles River Associates also raised questions about the reliability of power distribution without Indian Point. And their study estimates that the city's consumers would see their energy bills increase by 5 to 10 percent if Indian Point were to close.

A separate study, by Synapse Energy Economics, found that the cost increase to consumers might actually be far less, only 1 to 3 percent.

Koch said that when challenging a nuclear power plant “local governments feel powerless. The Congress has taken most of the power of local governments away and made it solely a function of a federal agency.”

A case in point is Vermont’s attempts to close Vermont Yankee, an Entergy plant situated on the Connecticut River, which have been unsuccessful to date. A challenge to Vermont Yankee’s license renewal failed last month in federal court.

Phillip Musegaas, director of Riverkeeper’s Hudson River Program, said that the debate about keeping Indian Point open boils down to one question: “If you don’t need the power, why take the risk? Its location is fundamentally problematic.”

When asked what he believed was the fundamental obstacle to closing Indian Point, Koch responded: “It’s called money. People invested billions in these plants … and are going to fight tooth-and-nail to protect these investments.”

NRC public hearings on Entergy’s application for renewal of Indian Point’s licenses are set to begin in October, though seismic risk and evacuation planning won’t be evaluated as part of the process. The reactors are currently licensed to operate until 2013 and 2015, respectively.

Challenges mount at Hudson River Park

Photo courtesy of the Hudson River Park Trust

It's the 50th anniversary of the building complex at Hudson River Park's Pier 40, and the aging, dilapidated commercial structure is in peril. The roof of the building's parking garage is falling in and the pier's support pilings are disintegrating as marine worm borers feed on them. The building itself has exposed wiring, rusted metal and a leaking ceiling. The halls are covered in graffiti.

Still, Pier 40, which is used daily by both ball clubs and commuters despite the need for emergency repairs to its pilings and roof, is in significantly better condition than nearby Pier 54, which can't currently support the weight of the public and is inaccessible.

These are just some of the growing problems at the Hudson River Park, a 550-acre park along Manhattan's western edge that draws over 17 million visitors a year.

At a recent meeting of the Hudson River Park Trust that drew nearby residents and environmentalists concerned about the construction of a natural gas pipeline that would run under the greenway, officials said the cost of making the repairs continued to balloon, with the work needing to overhaul Pier 40 alone estimated at $120 million.

The challenges have sent officials scrambling to find ways to raise revenue, floating several options including residential and retail use and a long-shot proposal to construct a Major League Soccer stadium on Pier 40. But any option would need to support the long-term financial health of the piers while also acquiescing to some of the community's demands.

Officials also said that the constraints of the Hudson River Park Act, created by New York state to establish the the greenway in 1998, limited their options and might need to be revised.

The park itself is only 80 percent complete, said Arthur Schwartz, a member of Community Board 2. At the same time, government funding has been cut from about $20 million a year to $6 million. The state has promised to fund the park to completion.

At the recent meeting, Trust president Madeline Wels said the urgency of the repairs and size of the costs calls for “creative” solutions that might well require an amendment to the Act. Emergency repairs alone will come to $80 million over the next 10 years, far exceeding both their reserve fund of $25 million and expected revenue.

“The park's intention was to be self-sustaining, and there's enough money for regular maintenance, but not for capital maintenance,” Wels said at the meeting. She noted that badly needed infrastructure repairs, some of which were caused by damage from Tropical Storm Irene and some from the marine worm borers “weren't anticipated.”

The Trust had expected a private developer to fix the problems at Pier 40, but no private developer has come forward to lease the property, and now the park is faced with covering the cost themselves.

Potential development proposals were analyzed by Tishman Construction and their findings were also presented at the meeting. Of these, the prospect for the most revenue, explained Jed Howbert, a Tishman representative, includes retail and residential use, ideas that officials acknowledged are unpopular with community members in the area. Regardless of what is developed, the Trust maintained that 50 percent of the park on Pier 40 would remain open space.

The proposal to create a Major League Soccer stadium on the pier had not been received in time to be included in Tishman's study, however, and Schwartz said questions remain regarding the impact on residents, as the stadium would bring in about 25,000 fans per game or event. The impact of a stadium would not be known until an official request for proposals is distributed, said John Kelly, a spokesman for the Trust.

If residents want to hear different proposals, Wels said at the meeting, the first step would be to amend the Act and extend the 30-year lease limit that is currently in place, a restriction that makes some development ideas untenable. The Trust would also like to see an amendment permitting the ability to bond for more money.

“We're trying to help the Trust sustain itself by amending the law,” said Wels. “We will get better proposals, too.”

But some residents at the meeting said any change to the law was going too far. Alison Tupper, a resident of the West 40s, acknowledged the dire budget hole, but said the real value of the greenway was its function as a park. “Changing the law could open the park to unintended consequences,” she said.

Assemblywoman Debra Glick, an outspoken critic of some of the Trust's proposals, argued that deteriorating conditions were being used as a reason to drastically and quickly rewrite the Act's restrictions before the close of the current legislative session.

“The Assembly has asked the HRPT for what their immediate need is so we have time to review things,” she said. “I don't think you make good decisions in crisis mode.”

The most urgent repairs are expected to cost approximately $15 million, she said, with $5.8 million going to Pier 40's most crucial repairs. Kelly said repairing the entire roof will cost $30 million, with an additional $90 million needed for repairing pilings.

“I'd like to see the city and state provide that emergency infusion to make those repairs right now in order to buy enough time for a more thoughtful discussion,” Glick went on.

She said more time was also needed to get comments from the public on the proposal to change the Act that created the park, considering the “significant changes” being presented. "It took 3 to 4 years to draft [the Act] after literally scores of public meetings," she said.

Glick described the meeting as “severely lacking” in public involvement, calling it little more than a presentation of the options the Trust seemed most inclined to promote. In fact, following the Trust's presentation, additional Trust members, largely repeating what was already said, were given the first opportunity to speak at a meeting with a limited time frame for public speakers.

The Trust insisted the meeting was a culmination of six months of “intensive exploration” with elected officials, community boards, and active community groups. Should the Act be amended, there will be a “built-in time for public feedback” following any plan to move forward with a development proposal.

Brad Hoylman, the Community Board 2 chair, said he was particularly frustrated by what appeared to be the city's apathy to the park's problems. Hoylman noted that Governor's Island would be receiving $260 million in city funds, a park used five months a year, while Hudson River Park is "used everyday of the year." He added that the city had provided money for the East River esplanade as well.

“We as west-siders have to ask, why aren't we getting a share of that money? They made plenty of money off of us,” he said.

Representatives for the city didn’t respond to requests for comment. The mayor has called Governors Island “the centerpiece of our efforts to revitalize New York City’s waterfront.”

___

Matt Hunger, a Brooklyn-based freelance journalist, writes on everything from municipal issues to the arts and sports. He can be reached at matt.hunger(at)gmail.com.

Exclusive: Proposed policy would allow industries to self-audit pollution-generating activities

Photo courtesy Hudson Riverkeeper

Industries that use pesticides, treat wastewater and store hazardous chemicals could have penalties for breaking pollution laws reduced or waived if they agree to self-report violations under a policy being considered by New York’s leading environmental regulator.

Any entity that enters into an agreement with the state Department of Environmental Conservation to self-audit would also “not be prioritized for inspection during the audit period,” stated a draft of the proposed policy obtained by the Gotham Gazette.

The DEC regulates sources of air and water pollution, including private industry, agricultural uses, and municipal facilities like waste transfer stations and sewage treatment plants. It is responsible for enforcing over 40 New York State environmental laws and over 50 federal laws, including provisions of the Clean Air and Clean Water acts. The agency would also be charged with regulating hydraulic fracturing in the Marcellus Shale.

The self-audit policy, described in a draft document dated May 14, would apply to any private business or public entity, including federal, state and municipal agencies and facilities, which are regulated under state environmental law.

A self-audit, however, “is not required for disclosure and may not be warranted in certain circumstances,” the document states. Environmental violations involving suspected criminal conduct would not be eligible for a penalty waiver.

Further, the DEC would conduct an inspection if it receives “a complaint concerning the regulated entity or have reason to believe that a violation has occurred resulting in serious actual harm.”

DEC Executive Deputy Commissioner Marc Gerstman said the goal of the proposed policy was to promote compliance with environmental laws.

“Nobody is being given a free ride or a ticket to pollute,” he said. Instead, the policy encourages companies to come forward when something goes awry. “If a company has a violation that they want to disclose, [they] have some comfort level that we will not impose penalties.”

The draft of the policy was distributed in the DEC’s central and regional offices for internal review. DEC officials also said the agency had “held stakeholder meetings with environmental groups, municipalities and businesses to get their input on developing a self-audit policy.” More meetings were planned, they said.

The federal Environmental Protection Agency would also have to clear the new policy. A spokeswoman for the agency said they were unaware of the proposed policy. The DEC said it had attempted to contact the EPA and would discuss it with their federal partner before it is finalized.

Read the draft DEC document below

Too unwieldy to implement?

The proposed policy has already stirred up some concern among current DEC employees who worry that it will be too unwieldy to implement given the agency's resource constraints. One worker who has conducted inspections and reviewed the document told the Gazette that “the glaring issue is who is going to review all these audits.”

“We don't have resources to keep up with normal enforcement,” said the employee, who was not allowed to speak about the policy publicly and spoke on the condition of anonymity. “If the audit policy becomes a priority, then enforcement becomes secondary.”

Since 2008, the agency has lost almost 800 employees, bringing staffing levels to their lowest point in over twenty years. Meanwhile, federal financial support for the DEC has steadily declined and the agency has become more reliant on New York State tax dollars and revenue from fees and penalties.

“Resource limitations” and “the high volume of activities potentially affecting human health and the environment as well as practical constraints” in part led the agency to develop the proposed self-audit policy and other “auxiliary strategies,” the draft document stated.

DEC spokeswoman Emily DeSantis said the policy would alleviate some pressure on personnel. “As more entities within the regulated community adopt approaches to assess environmental performance on their own, the policy will allow DEC to focus its enforcement efforts on the truly bad actors,” she said.

The Debate Over Self-Audit Agreements

Environmental self-audit and voluntary compliance policies have been used by both the federal government and sporadically at the state level since the early 1990s. The DEC’s newly proposed self-auditing program would greatly expand the agency's current use of self-reported information, representing a major shift in the state’s approach to environmental protection.

The proposed policy enables companies and other entities to enter into self-audit “agreements” with the DEC. These agreements can be comprehensive, covering all environmental laws and regulations applicable to a facility, or limited to a portion of those requirements. Companies and other regulated entities that commit through a self-audit agreement to minimize their impact using “environmental management practices and pollution prevention systems” would be offered a variety of incentives.

The incentives are still being developed but they could include public recognition of the company’s efforts and access to technical assistance services, according to the draft document. Perhaps more importantly, they could include additional assistance with penalties and timeframes for correcting violations.

Some critics argue that such self-auditing programs could lead to less frequent inspections, erode defined missions for state regulators and provide a shield for polluters against environmental enforcement and public oversight. Others said enforcement should be the focus of regulatory efforts.

Robert Sweeney, the Democratic chair of the state Assembly’s environmental conservation committee, said he was skeptical of the proposed policy, which he had not seen until it was provided to him by the Gazette.

“A better option would be to consider beefing up enforcement, which would pay for itself,” he said. In a subsequent email, he added: “It may be old-fashioned, but to keep people honest you need cops on the beat.”

Self-audit agreements could also deal a blow to transparency and acountability, said Bill Wolfe, director of the New Jersey office of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility. “There are no public hearings… no discoverable documents,” he said. “The audit becomes a way to stay private.”

But others saw a benefit to the policy. Richard Schrader, the New York State legislative director for the National Resources Defense Council, said a self-audit policy “make sense as one of the tools for environmental compliance.” But he said such a policy requires “great care and caution … [It] can’t be a substitute for ensuring that the DEC has adequate enforcement staff, and they still have to pursue full-compliance in an aggressive fashion.”

Darren Suarez, the government affairs director for the Business Council of New York State, said self-audit agreements could be beneficial to both the companies themselves and to “the goal of reducing degradation to the environment.”

“A self-audit helps to identify areas where an institution may not be handling materials as well as they would want to,” he said, and later added: “If they can come into compliance, that’s the big incentive.”

DEC spokeswoman DeSantis said the program would encourage “comprehensive company-wide audits and best management practices, designed to identify and correct violations without fear of significant penalties.”

“In the end, companies and municipalities that have strong systems in place to ensure environmental compliance will prevent violations down the line,” she said.

Learning From Experience

A “voluntary compliance” policy was previously attempted by the DEC in the mid-1990’s under then-Commissioner Michael Zagata. But one retired DEC staffer with knowledge of the enforcement process said the agency’s personnel grew reticent to follow up on reports of violations after the policy was in place.

Paul Gallay, a DEC attorney from 1990 to 2000 and now president of Hudson Riverkeeper, said of the Zagata period: “The hidden message was, â€We don’t have to enforce the way we used to.’”

Zagata, who is now the president and CEO of the Ruffed Grouse Society in Pennsylvania, said he could not remember if there was a written policy with clear parameters. But he said that voluntary compliance was something he was trying to push as a philosophy throughout the agency.

"Voluntary compliance, with the understanding that if you don't do it, there's a stick on the other side of the fence, is doable,” he said, but added that the agency would still need enough workers to verify noncompliance.

DEC administrative hearing records for a case settled in 2005 involving a gas station with registration and safety violations reference a backlog of enforcement cases due to the agency’s “voluntary compliance” program.

The case, which focused on the gas station’s underground tanks, took over a decade to resolve and hinged on whether the tanks were being tested for leaking that could seep into wells or other underground water sources.

“Although the tanks were due for testing in October 1992, DEC staff did not inspect the facility or take action to bring it into compliance with the testing requirement until June 2002,” hearing records stated. “This was part of an ongoing effort by DEC staff to reduce a backlog of overdue registrations and tank tests that had accumulated while the Department was pursuing a policy of voluntary compliance.”

Other states' experiences

As New York weighs a possible self-auditing policy, New Jersey is also re-visiting the idea after an earlier proposal was struck down. Meanwhile, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection has used a form of self-auditing in its Waste-Site Clean-Up program since 1993; it has considered expanding the policy into wetlands management but has not made a final determination.

Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility released a 2008 press release charging that the “failure rate” among companies who self-audited using private licensed consultants was found after a state review to be 70 percent (21 of 30 sites).

Paul Locke, director of response and remediation for the Bureau of Waste Site Clean-Up at the Massachusettes DEP, rejected the criticism. “That is not representative of the universe of submittals of site clean-ups that we get,” he said.

He argued that privatizing aspects of environmental auditing and oversight can be appropriate in contexts where licensed professionals are engaged in well-defined tasks. “You have to set up the system so that they are checking in along the way -- you have multiple checks and balances. It’s not as clear-cut as the Wild West of self-auditing,” he said.

Kyla Bennett, who runs the New England PEER office and worked for the EPA for ten years, said she believes there is an inherent conflict of interest in allowing private companies to pay for environmental audit services as opposed to relying on public enforcement.

“Is it a risk? Absolutely…. You can skew things in one direction or another. It happens all the time. The Massachusetts DEP doesn’t have the money to go after licensed professionals, let alone go after violators,” she said.

Stretching Resources

The policy draft says self-auditing will “supplement” existing DEC environmental enforcement activities. How well environmental enforcement is currently working and the DEC’s ability to keep up with inspections has been a subject of scrutiny, especially given the DEC’s loss of staff.

Commissioner Joseph Martens told the Gazette in March that the DEC will not see an increase in staff “anytime soon,” due to the state’s fiscal situation. The draft’s reference to DEC’s resource limitations raises the issue of how the agency has searched to find ways to meet state and federal mandates.

A DEC employee with knowledge of the state’s petroleum bulk storage program, which regulates oil storage facilities of over 1,100 gallons typically found in gas stations, medium to large industrial businesses and public buildings, said private contractors have been brought in to help with the inspection backlog because the program is so shortstaffed.

The program is run in conjunction with the federal EPA. The employee, who was not allowed to speak publicly about the program and did so on the condition of anonymity, explained: “This year, over 24,000 PBS sites have overdue tank registrations. Historically we would send out notice of violation letters and attempt to get a penalty. DEC would get responses and that would be the ones we would work on. The ones who did not respond was a low priority. Think of the volume. No way can the DEC handle that volume effectively, not then and not now. We are trying to prioritize the volume of non-compliance. But I see this as a failure in the [PBS] regulation and its attempt to prevent oil spills.”

The DEC disputed the employee’s claim, saying that only 4,600 PBS registrations were more than 90 days overdue. Fewer than 600 are less than 90 days overdue. The DEC said most of the overdue regustrations were heating oil tanks, “which are generally overdue because they have been sold or have changed management companies.”

“DEC has and continues to promote compliance and do enforcement as necessary for these overdue registrations,” said DeSantis, the agency spokeswoman. “This enforcement is done every year and has been ongoing since 1997 when we had more than 8,000 facilities overdue for registration.”

The DEC has acknowledged that they stopped performing effluent sampling as a regular part of the State Pollutant Discharge Elimination System inspection program in fiscal year 2010-2011 after significant staff loss. Any facility that discharges into surface water needs a permit, including manufacturers, power plants and sewage treatment plants. The DEC uses self-reported data from regulated pollution sources as part of the SPDES program.

According to Environmental Advocates, a watchdog group that monitors the DEC, in 1990, the DEC sampled effluent 1,113 times to verify polluters’ reports.

In 2008, the DEC took 112 samples, a 94 percent decrease. The DEC said the sampling is not required by law. “This information continues to be self-reported by the permitees,” the agency previously told the Gazette.

Conclusion

The New York DEC is completing an internal review of the self-audit policy before introducing it more broadly. The agency has not indicated whether the policy would be tested out in one division first, or if it would apply to all of DEC's enforcement work. New York State Legislative approval for adoption of the policy is not required. The DEC’s Gerstman noted that the agency is “coordinating with the federal EPA as a partner.”

Suarez, of the Business Council, said the right questions to be asking are “what do you ultimately want to see and how do we get there? And (can this) allow businesses to stay here?”

Hudson Riverkeeper’s Gallay said there was a way to balance environmental law with business interests while also enforcing penalties. “When I worked for the DEC, we took great pride in bringing companies back into environmental compliance and economic health. You don’t need penalty forgiveness policies to do that,” he said.

The DEC has sole discretion to select eligible businesses and other entities for participation in self-audit agreements, the draft document states, and to exclude “bad actors” that have a history of non-compliance. Regulated entities that own or operate multiple facilities can still be eligible even if one of their facilities is under investigation.

Federal Reports Warn of Staff Shortages at DEC

Staffing and resource shortages at the Department of Environmental Conservation’s (DEC) Shellfisheries division have been flagged as an “emerging problem” by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA program evaluation reports released in late 2011 cite staffing-related issues in three of the Shellfisheries division’s four units. A January 2012 letter to DEC Commissioner Joseph Martens, which accompanied the FDA’s bi-annual evaluation of the division, notes that one of the units, “May be currently stretched to its operating limits. FDA encourages the DEC to invest the necessary resources to keep the Growing Area Classification Program in compliance (…) the FDA is concerned with the loss of staff in the Growing Area Classification Unit which is critical to protecting public health.”

In an interview last month with Gotham Gazette, Commissioner Martens stated that the DEC will not see an increase in staff “anytime soon” due to the state’s fiscal situation. The DEC has lost almost 800 employees since 2008. Agency staffing levels are at their lowest point in over twenty years.

Monitoring Shellfish Safety

The DEC’s Shellfisheries division monitors water quality in state shellfish growing areas, and regulates the harvest, handling and processing of shellfish. The division is part of the DEC’s Bureau of Marine Resources (BMR), and is responsible for both maintaining the state’s shellfish resources and protecting public health. Shellfish are an important part of New York’s multi-million dollar seafood industry. Clams, mussels, scallops and oysters comprise over half of the state’s commercial catch, according to the New York Seafood Council, a non-profit industry association. Because shellfish pump and filter water through their bodies, they can absorb pollutants, bacteria and other contaminants, which can lead to illness when the fish are consumed. DEC’s Shellfisheries division works in conjunction with federal agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency and the Food and Drug Administration to maintain national sanitation standards within the New York shellfish industry. Local municipalities are also responsible for monitoring shellfish-related activity, but the DEC is responsible for establishing and maintaining baseline regulations.

A DEC staff person speaking on condition of anonymity pointed out that of any division at the DEC, Shellfisheries has the most acute link to public health. “What we do is directly public health related every day. It's just part of what we do…Contaminated or spoiled shellfish could get out and people could get sick.” Earlier this month, the Shellfisheries division closed portions of Shinnecock Bay and Mattituck Creek in Suffolk County due to the appearance of biotoxins, which are naturally occurring but are potent neurotoxins when ingested. Monitoring and preventing biotoxin contamination is a relatively new challenge for the DEC. The State first closed shellfish areas due to the identification of biotoxins in 2006, and the plankton blooms have appeared along the Northeastern seaboard. The presence of biotoxins in New York shellfish growing areas occurred a month earlier than anticipated this year. Says the DEC staffer, “this problem has expanded. We have no more people to do the work. It is pushing us to the limit.”

The FDA Weighs In

The FDA praised the Shellfisheries division’s “pro-active” development of a biotoxin monitoring system in its 2011 review. It also determined that the division’s growing area classification unit, which monitors sources of water pollution in about a million acres of marine and ocean territory, was not in full compliance with federal regulations. Monitoring water pollution is especially critical in New York because the Long Island coastline is densely populated. National Shellfish Sanitation guidelines require that DEC biologists conduct a series of shoreline surveys targeting sources of pollution, such as water treatment plants, that can impact shellfish areas.

The shoreline surveys are re-done every 12 years on a rotating basis as pollution sources change. The surveys are then used to set up water sampling stations, which enable the Shellfisheries division to accurately classify the safety of growing areas. Water sampling is conducted year round.

The FDA flagged an open growing area which had not been surveyed since 1994, along with sampling data that needed completion. Growing areas whose surveys are not up-to-date are eventually closed until current information is obtained. These closings impact the local shellfish industry. The survey report and sampling were subsequently completed and the growing area classification unit is back in compliance.

But the FDA discussed the resource strain caused by increased biotoxin monitoring and the re-opening of "conditional" harvesting areas closed because of earlier budget cuts. According to the FDA, the growing classification unit “is already highly dependent on borrowing staff and resources from other programs to accomplish minimally required field activities.” The unit will be reviewed again this year. In a written response to questions about the FDA review, Emily DeSantis, DEC’s Director of Public Information, stated, “we provided the USDA with an action plan to address the non-conformities in the Growing Area Program. We have implemented that plan.”

Staffing and Funding Issues

The 2011 FDA review also found staffing related issues in the DEC’s Shellfisheries plant inspection and lab units. The Shellfisheries division has a dedicated unit which inspects wholesale plants and shipping facilities where oysters, clams, etc. are unloaded and processed for distribution. The unit is an important part of the safety process because they are looking for potential cases of spoilage and poisoning before product heads to restaurants and stores. The FDA recommended to DEC in 2011 that the agency fill two vacant inspector positions, stating “that at current staffing levels, it will be nearly impossible for DEC to achieve the minimum number of plant inspections required under the NSSP ordinance in the future.” Emily DeSantis responded that the agency has filled one of the plant inspection unit’s two vacant positions, and that “we feel that we are adequately staffed at this time.”

The FDA review also discusses instances when the Shellfish Sanitation Program was constrained by lack of funding for additional testing, equipment, and staff time. According to the FDA, during the biotoxin closures in spring 2010, DEC staff sent samples out of state for analysis as they tried to secure funding for a specialized form of testing that could be performed locally. The Division’s Vp monitoring program, which tests for strains of a particular pathogen found in Oyster Bay in 1998, has been suspended since 2009 due to lack of funding. According to the FDA, Vp-related illnesses spiked in 2009 and sporadic cases occurred in 2010. “Several (cases) may have had associations to shellfish harvested in New York waters.” The FDA discussed the Shellfisheries division’s inability to purchase gene-probe materials, and questioned whether “such monitoring may have prevented Vp-contaminated shellfish from being sold and consumed if DEC-BMR had the necessary screening materials sooner.”

Cutbacks

DEC has administered other cost cutting measures impacting the Shellfisheries division, such as restricting overtime, which the FDA argues has “Significantly reduced the time frame for accomplishing water sampling…and has resulted in 30% loss of sampling opportunities.” Samples previously gathered over a 5 day period must now be gathered in 3 or 4 days. The necessity for water sampling activity has increased as the division responds to the evolving biotoxin situation each spring. According to the FDA, the compression of sampling activity due to funding restrictions has “overwhelmed” DEC’s shellfisheries lab because samples must be processed rapidly. The FDA has also proposed that the lab may need another technician.

The FDA’s most recent reports raise a number of questions about how far resources can be stretched before core functions that protect public health and natural resources become untenable. The FDA did not comment on this story. The DEC has argued that some of the impact of recent staffing losses throughout the agency can be mitigated by efficiency and technology improvements. An anonymous source within the Shellfisheries division observes, “(we are) constantly in catch-up mode. It’s grinding people down. You don’t do more with less. You can only do less with less.” In reference to the division’s work to track biotoxins and man-made pollution sources in the state’s shellfish growing areas, he adds, “We are just marginally keeping our heads above water. At some point we will fall too far behind.”

Where Tech and Environment Meet

Photo by Jonathan Camhi

Lief Percifield wants to let New Yorkers know about possible sewage seeping into their drinking water.

Every year 27 billion gallons of untreated sewage are released into New York Harbor during Combined Sewage Overflows, causing a number of health concerns. Percifield explains that a Combined Sewage Overflow occurs when rainwater overloads the city’s sewage pipes. The pipes then spew the rainwater and sewage out of overflow points along New York Harbor to keep from flooding the sewers.

Percifield, a graduate student at Parson’s, wants to place sensors at these overflow points that would detect Combined Sewage Overflows and alert New Yorkers when they are occurring. If New Yorkers conserve more water during the overflows, then less sewage will be spit out into the harbor, he says.

Percifield would like to sell light bulbs that would turn color to indicate an overflow that people would place in their kitchens or bathrooms. People would then wait until the overflow subsides (they usually last 4-6 hours) before doing their wash or taking a shower.

But Percifield still hasn’t worked out many details of his alert system. For instance, he’s not sure how to manufacture some components of his system in a cost-effective way, or how he will distribute the light bulbs.

“I would hope that Home Depot would sell them at some point. In the short term I have no idea,” he says.

He might not have every part of his plan worked out, but his project still caught the eye of In Our Backyards, an organization that raises funds for local environmental projects around New York City. With the organization’s help, Percifield raised $3,240 to get his project off the ground and build his first sensor and light bulb prototypes. He has installed his first sensor at an overflow point on the Gowanus Canal by Bond St. and 4th St. and he now has a light bulb in his bathroom telling him not to shower when a Combined Sewage Overflow is happening. Percifield says he is now talking with the city’s Department of Environmental Protection about helping him install and maintain his sensors.

“Crowd-Resourcing”

In Our Backyards has helped fund over 125 other green projects like Percifield’s since it started in May 2009. Erin Barnes, one of the organization’s co-founders, says they call themselves a “crowd-resourcing” organization, combining crowd funding through their website and resource organizing in terms of helping their projects find volunteers and network with other organizations.