How the NYPD overstated its counterterrorism record

The NYPD is regularly held up as one of the most sophisticated and significant counterterrorism operations in the country. As evidence of the NYPD's excellence, the department, its allies and the media have repeatedly said the department has thwarted or helped thwart 14 terrorist plots against New York since Sept 11.

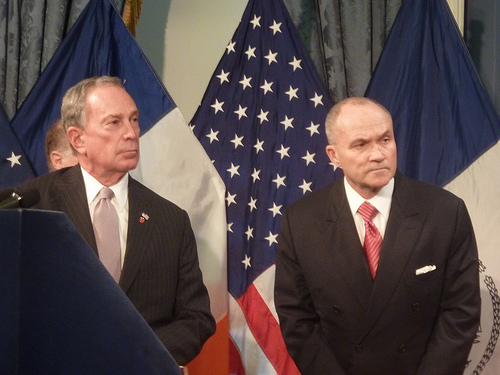

In a glowing profile of Commissioner Ray Kelly published in Newsweek last month, for example, journalist Christopher Dickey wrote of the commissioner's tenure since taking office in 2002: The record "is hard to argue with: at least 14 full-blown terrorist attacks have been prevented or failed on Kelly's watch."

The figure has been cited repeatedly in the media, by New York congressmen, and by Kelly himself. The NYPD itself has published the full list, saying terrorists have "attempted to kill New Yorkers in 14 different plots."

As Mayor Michael Bloomberg said in March: "We have the best police department in the world and I think they show that every single day and we have stopped 14 attacks since 9/11 fortunately without anybody dying."

Is it true?

In a word, no.

A review of the list shows a much more complicated reality 2014 that the 14 figure overstates both the number of serious, developed terrorist plots against New York and exaggerates the NYPD's role in stopping attacks.

The list includes two and perhaps three clear-cut terrorist plots, including a failed attempt to bomb Times Square by a Pakistani-American in 2010 that the NYPD did not stop.

Of the 11 other cases, there are three in which government informants played a significant or dominant role (by, for example, providing money and fakes bombs to future defendants); four cases whose credibility or seriousness has been questioned by law enforcement officials, including episodes in which skeptical federal officials declined to bring charges; and another four cases in which an idea for a plot was abandoned or not pursued beyond discussion.

In addition, the NYPD itself does not appear to have played a major role in breaking up most of the alleged plots on the list. In several cases, it played no role at all.

The NYPD did not respond to requests for comment on the list of 14 alleged plots and how it was assembled. A spokesman for Bloomberg declined to comment.

The following is a breakdown of the plots on the NYPD's list.

Substantially developed or executed plots:

-

The failed 2010 attempt by Faisal Shahzad to set off a crude car bomb in an SUV in Times Square. Shahzad was in contact with the Pakistani Taliban before and after the attempt, according to the government, and he pleaded guilty to charges stemming from his role in the attempt.

The plot was widely seen as a law enforcement failure, as Shahzad was able to plant the rigged car in Times Square without being on the radar of the NYPD and other agencies.

-

The thwarted 2009 plot by three former high school classmates from Queens to set off bombs in the subway system. One of the plotters, an Afghan immigrant named Najibullah Zazi, testified in court this year that he and the others had received training from "Al Qaeda leaders" in Pakistan. He also admitted bringing bomb-making materials into New York. All three men have pleaded guilty or been convicted of terrorism charges. According to the AP, the plot was uncovered not by the NYPD, but rather by an email intercepted by U.S. intelligence.

-

Transatlantic Plot In August 2006, British authorities arrested a group of men who were later charged with plotting to blow up planes bound for North America from London with liquid explosives. (This is the plot that led to restrictions on carrying liquids aboard planes.)

The plot is included on the NYPD's list of 14 because, according to British authorities, one of the men had a memory stick that had information on flights bound for several Canadian and American cities, including, in one case, New York. The plan was to blow up the planes over the ocean.

During the trial, there were questions about whether the men were going to act on the plan imminently. Three consecutive trials in the case ultimately resulted in eight convictions. The NYPD was not involved in thwarting the plot.

Cases with significant or dominant role by government informants:

-

The case of the Newburgh Four, in which four men from upstate New York planted what they thought were real bombs outside synagogues in the Bronx. The men were found guilty in the case in 2010 after the jury rejected an entrapment defense. The bombs were fakes supplied by the government.

An informant posing as a Pakistani terrorist recruited Walmart employee and Muslim convert James Cromitie over nearly a year, giving him gifts, including rent money and a trip to an Islamic conference. The informant plied Cromitie with offers of $250,000, a luxury car and a barbershop. An FBI agent on the case acknowledged under cross-examination during the trial that the government was essentially in control of what the four were doing while they were with the informant. The government maintained that Cromitie was an anti-Semite who talked about committing acts of violence and posed a real threat.

A judge who rejected an appeal last year nevertheless called the government's conduct in the case "decidedly troubling."

-

Herald Square Pakistani immigrant Shahawar Matin Siraj was arrested in 2004 and convicted in 2006 at the age of 23 of conspiracy to bomb the Herald Square subway station in Manhattan. The jury rejected an entrapment defense.

An informant for the NYPD's Intelligence Division played a key role in the case and was paid $100,000 by the government over a roughly three-year period. He told Siraj he was a member of a (made-up) group called "the Brotherhood" that would support a bomb plot. Siraj was recorded talking to the informant about blowing up bridges and other places in New York, including the Herald Square subway station. The informant later told Siraj that the Brotherhood had approved the plot and that a leader of the group was "very happy, very, very impressed" with the idea. The informant told Siraj the group wanted him to put backpack bombs in the station, and he drove Siraj and another man to the station to do surveillance.

At his sentencing, Siraj apologized to the judge but maintained he had been "manipulated" by the NYPD informant. Siraj did not obtain explosives, there was no timetable for the plot, and there was no link to any foreign terrorist group, according to the Times.

-

JFK Airport Russell Defreitas, a naturalized American citizen from Guyana and former airport cargo handler, and Abdul Kadir, of Guyana, were arrested in 2007 and convicted in 2010 of conspiring to blow up fuel tanks at JFK airport.

At the press conference announcing the charges, a federal prosecutor said the public was never at risk. A law enforcement official described Defreitas, 63 at the time of his arrest, to the New York Times as "a sad sack" and "not a Grade A terrorist." Pipeline experts told the paper that the men's plan to blow up a wide area was not feasible.

Defreitas was recorded making odd comments talking to the informant, saying he wanted the attack to be "ninja-style" and that the airport was a good target because "They love JFK -- he's like the man. If you hit that, the whole country will be in mourning."

An informant on the case was a convicted drug dealer paid by the government and worked in exchange for a lighter sentence in a pending drug case. He drove Defreitas to the airport several times to do surveillance with a camera that the informant had purchased for Defreitas. The informant also provided plane tickets to South America and, with the help of the FBI, secured a New York City Housing Authority apartment for Defreitas (that was under surveillance).

U.S. officials (often anonymous) question credibility or seriousness of cases:

-

The case of Jose Pimentel, a Manhattan Muslim convert who was arrested in November 2011 on "rarely used state-level terrorism charges" after federal authorities took a pass on the case.

Manhattan District Attorney Cy Vance Jr. alleged that Pimentel had been "building pipe bombs to be used against our citizens." City authorities said Pimentel had no contacts with foreign terrorist groups and called him a "lone wolf."

In a series of leaks, federal authorities expressed skepticism that Pimentel was a threat. A federal source told the New York Post that Pimentel was a "'stoner' who wasn't a real danger to anybody other than himself." Another source cited by the Post questioned his mental faculties, saying he had once tried to circumcise himself. A federal source told DNAInfo criminal justice editor Murray Weiss: "Let's just say there were issues whether [Pimentel] had the ability to do this without the intercession of the confidential informant." Weiss also noted that the informant went shopping with Pimentel at Home Depot to buy pipe bomb materials, and the bomb was constructed at the informant's apartment. Pimentel, who reportedly could not afford to even pay his cell phone bill, has pleaded not guilty.

-

The case of Ahmed Ferhani and Mohamed Mamdouh, alleged "Islamic extremists" and "lone wolves" who lived in Queens and were arrested in May 2011 after buying guns, ammo, and an inert grenade from an undercover police agent. The authorities alleged that the two men were planning to attack a New York synagogue because they were upset with how Muslims were being treated around the world.

But the case was another example of an alleged plot that the FBI took a pass on. Citing federal law enforcement sources, WNYC reported that the FBI passed on the case because the bureau found the undercover operation "problematic" and the allegations "over-hyped." And the website NYPD Confidential reported that Ferhani has a history of mental illness.

The AP noted the case faltered early on when a grand jury declined to indict the two men on a high-level terrorism conspiracy charge. Both have pleaded not guilty to lesser terrorism charges.

-

Brooklyn Bridge Ohio truck driver Iyman Faris pleaded guilty in 2003 to providing material support to al Qaeda; he met with senior al Qaeda leaders abroad and researched how to attack the Brooklyn Bridge. Terrorism analyst Peter Bergen has called Faris "an actual al Qaeda foot soldier living in the United States who had the serious intention to wreak havoc in America" but "not much of a competent terrorist." Bergen wrote the plan Faris researched to sever the bridge's cables with a blowtorch as "akin to demolishing the Empire State Building with a firecracker."

The plot never got off the ground. According to the Justice Department, Faris sent messages to Pakistan "indicating he had been unsuccessful in his attempts to obtain the necessary equipment." According to the DOJ, Faris also concluded after a trip to New York that the idea "was very unlikely to succeed because of the bridge's security and structure."

-

PATH Train In 2006, 31-year-old Assem Hammoud was arrested in Lebanon. FBI officials announced that he and others 2014 who had never met but communicated on the Internet 2014 had been plotting a suicide attack on subway tubes under the Hudson River.

The Washington Post quoted U.S. counterterrorism officials questioning the credibility of the plot, reporting that they "discounted the ability of the conspirators to carry out an attack." One official described the matter as "jihadi bravado," adding, "somebody talks about tunnels, it lights people up." A counterterrorism official told the Times, "[t]hese are bad guys in Canada and a bad guy in Lebanon talking, but it never advanced beyond that."

Hammoud never visited the U.S., and there were no charges brought against him here. In 2012, Hammoud was sentenced to two years in prison in Lebanon, which he had already served.

Cases in which an alleged idea for an attack was not pursued:

-

"Subway cyanide" This alleged plot, first detailed by journalist Ron Suskind in 2006, was reportedly for a chemical attack on the New York subway system. Suskind reported that a U.S. intelligence source had said that al Qaeda was considering such an attack in 2003 but ultimately abandoned the idea. There is no evidence that the NYPD or any other law enforcement agency played any role in al Qaeda's decision to abandon the idea. There were also reported doubts about the quality of the intelligence and the credibility of the alleged plot.

"None of it has been confirmed in three years," a U.S. official told the Times, "who these guys were, whether they in fact had a weapon, or whether they were able to put together a weapon, whether that weapon has been defined and what it would cause or whether they were even in New York."

-

"NYSE/ Citi HQ" A British citizen named Dhiren Barot or Issa al-Hindi was arrested in the U.K. in 2004 and pleaded guilty two years later to conspiracy to murder. He had attended terrorist training camps and had contacts with Sept. 11 mastermind Khalid Sheik Mohammed, according to the government. He had taken video and photos of landmark sites in New York in 2000 and 2001 including the New York Stock Exchange and the headquarters of Citigroup.

An appeals court later reduced his sentence from 40 to 30 years, citing the "uncertainty" as to whether Barot's conspiracy would ever have amounted to an actual attempted attack, and the court's conclusion that one of the ideas for an attack in the United Kingdom was "amateurish." The appeals ruling also noted that after Sept. 11, Barot's plans for any attack in the U.S. "may have been 'shelved'" to focus on the U.K. The court also noted that there was no evidence that al Qaeda leadership had endorsed any of the ideas. Prosecutors also accepted that there was no money or equipment lined up for any of the ideas.

There is no evidence the NYPD had any role in the investigation that led to Barot's capture.

-

Garment District Uzair Paracha, a young Pakistani living in the United States, was convicted in 2005 of providing material support to al Qaeda. Prosecutors said that Paracha had tried to help a Pakistani al Qaeda member named Majid Khan gain entrance to the U.S., including a scheme to fool immigration authorities into letting Khan into the country.

The NYPD list says that "Paracha is reported to have discussed with top al Qaeda leaders the prospect of smuggling weapons and explosives 2014 possibly even a nuclear device 2014 into Manhattan's Garment District through his father's import-export business." But the indictment against him makes no mention of any such plot.

Instead the NYPD appears to be referencing a claim by Khalid Sheik Mohammed to American interrogators that Paracha's father, who is currently a Guantanamo detainee, discussed a plan with KSM to smuggle explosives into the U.S. through an import business he co-owned in Manhattan's Garment District.

KSM said he wasn't sure of the son's involvement and neither the father nor son has been charged with anything related to it.

According to the government's detainee assessment on the father, Saifullah Paracha, KSM said he wanted to use the explosives "against U.S. economic targets" but New York is not mentioned. KSM told interrogators that another man was to "rent a storage space in whatever part of the U.S. he chose" to hide the explosives. There is no claim in the detainee assessment that the idea ever got beyond discussion. Saifullah Paracha has denied the accusation. Mohammed also later told the Red Cross that in the period when he made the claims about the Paracha, shortly after his capture in March 2003 when he was apparently being subject to torture, he gave "a lot of false information" to interrogators.

-

Long Island Railroad Bryant Neal Vinas, an American Muslim convert from Long Island, was arrested in 2008 in Pakistan by authorities there. In 2009, then 26, he pleaded guilty to providing material support to and receiving training from al Qaeda. He told the court he "consulted with a senior al Qaeda leader and provided detailed information" about the Long Island Railroad in a discussion of a possible attack.

But in a trial in 2012 in an unrelated terrorism case, Vinas testified that to his knowledge the railroad idea was not pursued beyond discussion. Published reports do not mention any NYPD role in the case.

Are there alternatives to stop-and-frisk?

NEW YORK — In a manila envelope on the table in front of Marlene Steele are hundreds of letters from businesses, churches and foundations politely rejecting her request for help to fund a gun buy-back program at a nearby public housing complex. “No one wants to help me,” she says. “Is it something I’m doing wrong?”

The question prompts tears and a quick exit to the bathroom. Resurfacing, Steele tells how, in two weeks, her son and only child would have turned 20. Last July, according to news reports, hours after leaving a barbecue at the Queensbridge Houses, her son, 19-year-old Mark Torres, died from a gunshot wound to the head.

She is now working to get guns off the street so that no other children should die.

Police say that getting gun violence is one of the main justifications for stop-and-frisk -- of the 500 homicides the city averages annually, 60 percent are committed with a firearm.

But critics of the stop-and-frisk say it illegally targets mostly black and Latino youth, an argument supported by the police department's own statistics: Of the nearly nearly 700,000 stops last year, 87 percent of those stopped by officers were black or Hispanic. And their opposition of the crime reduction strategy grows louder each day.

Yesterday, thousands of people marched silently down Fifth Avenue from Harlem to Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s Upper East Side town house to call for an end to stop-and-frisk.

But what, exactly, could take its place? Gun buybacks like the one Steele is trying to raise money for are seen by some community residents as an alternative, though criminal justice experts say there is little evidence that they work to get illegal firearms off the street. Other alternatives include anti-gang initiatives and gun control programs that have proven successful in some big cities – but for each of these, like gun buybacks, the obstacle is one of resources.

Bloomberg has said stop-and-frisk needs to be modified, not ended. Speakingat the Christian Cultural Center in Brooklyn yesterday, he said he understood why some people want the city to end the strategy.

“Innocent people who are stopped can be treated disrespectfully. That is not acceptable," he said. "If you’ve done nothing wrong, you deserve nothing but respect and courtesy from the police. Police Commissioner Kelly and I both believe we can do a better job in this area – and he’s instituted a number of reforms to do that."

In a letter to the City Council speaker last month, Kelly outlined a number of changes to the policing strategy, including requiring top-ranking officers in each precinct to audit reports of street stops by patrol officers.

A Search For Alternatives

Unimpressed by stop-and-frisk, however, Steele, who is the director of operations for Gifted Community Services, took the initiative late last year to pursue what she considered a more effective solution: gun buybacks. She was excited at first. But then the rejection letters started to pile up. Phone calls to local churches went unreturned.

At a standing room only forum of about 150 Harlem residents this May convened to debate the alternatives to stop-and-frisk, the loudest applause of the evening went to one passionate young man who wanted to know why gun buybacks – with one-day takes rivaling those of a year of stop and frisk – weren’t “happening 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year.”

But experts say buyback events, or more accurately, amnesty programs for turning guns over to local police for a gift card, no questions asked, are ineffective.

“There isn’t any evidence that [they] reduce street crime,” says Jon Vernick, co-director of the Center for Gun Policy and Research at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Returned guns tend to be non-working or older weapons like revolvers, not the newer pistols used in street crime, participants tend not to be the young black and Latino males who’re most affected by violence and, finally, they don’t get that many guns off the street.

They are also extremely costly. It helps to explain why, at most, only up to four buybacks have been held each year in each borough since NYPD implemented the program in 2008. With a $184,000 price tag and a yield of 919 weapons, Queens’ last buyback was three years ago.

Steele remains undeterred. For her, the buyback is a high-profile teaser to gather her target audience for a main course of community dialogue, on-site therapy and advising from formerly incarcerated men and women. “I want to show people how good life could be without a gun,” she says.

At the Harlem forum in May, David Kennedy, director of the Center for Crime Prevention at John Jay College said an alternative might be “focused deterrence,” or, the opposite of what critics describe as stop-and-frisk’s dragnet approach.

Kennedy’s policing methods enlist community members to zero in on specific suspects in high crime neighborhoods—never more than a few people, he theorizes—and it has been proven successful in cities like Cincinnati, Boston and Chicago. New York City may be next.

This February, Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced an anti-gun initiative, which includes testing Kennedy’s approach for the first time in six sites around the state, three of which are in Brownsville, and parts of the Bronx and Manhattan.

A second promising option is the precariously funded Operation SNUG (“guns spelled backwards”) anti-gang and guns program.

Currently based in 10 sites throughout the state, including three in New York City, it replicates the successful Chicago model featured in the documentary “The Interrupters,’ and employs ex-convicts to work the scenes of violence and dissuade escalations.

“SNUG gets to the root of the problem, the person’s motivation for wanting to shoot in the first place,” says state senator Malcolm Smith, a Democrat from Queens.

He also sees another advantage to the program. “Unlike stops, which can leave anger, the SNUG approach to gun violence requires that communities join forces with the police department,” he says.

A Modified Stop-and-Frisk

Some critics says that ending stop-and-frisk altogether is not only a bad idea but impossible.

“Police officers need stop-and-frisk,” says retired NYPD Detective Carlton “Chucky” Berkeley, who regularly counsels youth and adults on how to have safe encounters with police officers. “When you stop someone, you don’t know what they’re carrying. If they have a bulge, for the safety of the officer, you have to frisk.”

In 1968, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed. Officer safety – not seizing weapons – was the often cited rationale behind the court's landmark Terry v. Ohio decision, which lowered the standard for performing a street stop from probable cause to reasonable suspicion.

The case gave officers legal leeway to briefly detain anyone reasonably suspected of having committed, being in the process of or about to commit a crime – and pat them down if they also reasonably suspected the person carried a weapon.

New York state’s stop-and-frisk law predated the Terry decision by about four years and, from the beginning, it was controversial.

In one of many government-commissioned reports examining the roots of social unrest, civil rights activist and Harlemite Bayard Rustin describes the tactic as a permit to harass “the poor and minorities like Negroes and Puerto Ricans.” Retired NYPD Detective Ray Figueroa says, in practice “we didn’t stop-and-frisk without first having a lot of probable cause. And I mean, a lot – like actually seeing the weapon.”

Other than anecdotal evidence, between 1964 and 1997, it is impossible to know how often the practice occurred, the rationale behind those stops or whether, as Rustin claimed, it was tailored to target minorities. It took the shooting death of unarmed 23-year-old immigrant, Amadou Diallo by four police officers in 1999 and the ensuing citywide outcry to launch the first state and federal investigations into stop-and-frisk. That year also saw the first public release of the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk data, which had been collected since at least 1986.

But even by 2002, the year that mandatory reporting of stop data to the city council took effect, the policy had not been deployed to the extent that it is today. Stops have increased 600 percent, after the crime rate had already fallen to historic lows.

Criminologists, retired police officers and recent whistleblowers like officers Adrian Schoolcraft and Adil Polanco allege the exponential uptick in stops can be traced to COMPSTAT, the computerized system that police have used to track and target crime.

Beginning in 1994, critics charge that the NYPD’s widely-replicated crime metrics system fostered a department-wide reliance on quotas to measure performance.

“Officers are being ordered to do things that many find ethically dubious,” says John Jay criminologist Eugene O’Donnell, also a former police officer and prosecutor. “If I frisk you for no good reason, then I’m filling out paperwork that may not be accurate, I have to go to court and swear to things that are not accurate.”

Whether the NYPD boosted stops to meet set performance targets is central to the upcoming federal trial, Floyd v. City of New York. Amid growing public scrutiny, Mayor Bloomberg conceded at a Brownsville church last Sunday that stop-and-frisk encounters should emphasize professionalism. But critics want reforms to go further.

“Every school and corporation in America goes through an accreditation process, but we don’t require that of our police departments," says John Eterno, a former NYPD captain and stop-and-frisk trainer, who is now chair of criminal justice at Molloy College. "It’s time to question why not, and demand that oversight of the NYPD and transparency be a part of stop-and-frisk reform."

They mayor and police have argued that there is sufficient oversight of the NYPD.

John Jay criminologist Eugene O’Donnell, also a former police officer and prosecutor, laments the way that the city has abandoned social policies other than criminal justice since the Giuliani era, and maintains that stop-and-frisk abuses are rising, in part, because “the police have been pressed into action to cover a gaping hole in our gun policy.”

“It is unethical,” he says, “to promise that we can pave the way to a great city with police, jails and courts. You cannot rely on the criminal justice system to make everything better.”

___

Carla Murphy is an independent journalist. Follow her at Twitter.com/carlamurphy

Cab driver sex trafficking bill passed by Council

NEW YORK – Cab drivers caught willingly transporting sex trafficking victims could face a fine of $10,000 and have their license automatically revoked under legislation passed by the City Council today.

The legislation passed at the Council's stated meeting also calls on the Taxi and Limousine Commission to develop a program to educate city-licensed drivers on laws prohibiting the use of taxis for trafficking.

"We are recognizing in this legislation the unconscionable and cruel role that taxi drivers and livery drivers are playing in this brutal attack that keeps people trapped, takes their lives away from them," Council Speak Christine Quinn said at a news conference before the legislation was passed.

Advocates for victims of sex trafficking said the legislation targets both traffickers and demand.

“Taxi drivers and livery drivers are often middlemen between trafficked people and the customers that create the demand,” said Sonia Ossorio, president of National Organization of Women New York City.

Currently, city-licensed taxi drivers could face a hearing if they commit a sex trafficking crime.

TLC spokesman Allan Fromberg said the agency was working with the Council to develop the educational component of the legislation. "The TLC will develop the most effective, and most cost-effective, program possible once the bill becomes law," he said.

In April, Manhattan prosecutors charged a father and his son with running a sex-trafficking ring, with livery cab drivers transporting prostitutes and arranging meetings with clients. The father and son, who have pleaded not guilty, were accused of threatening violence against the women for being late or failing to meet quotas.

Advocates said the case had highlighted the problem of livery drivers aiding sex trafficking.

Dorchen Leidholt, the legal director of Sanctuary for Families, a leading nonprofit that helps victims of domestic violence and sex trafficking, said a growing number of its clients had been "victimized not only by their traffickers but by drivers who were driving them from customer to customer, taking half the money that was earned and working very closely with the traffickers."

Bharavai Desai, the executive director of the Taxi Workers Alliance, said unlicensed cab drivers were most often linked to such crimes.

"There is no iota of evidence linking yellow medallion taxi cabs to sex trafficking," she said. "They are scapegoating our name. The City Council should address the issue but not scapegoat or link illegal services to legal services."

The Council also passed a resolution, created by 23 council members, that strongly recommends that the state Legislature pass the Trafficking Victims Protection and Justice Act. If passed, the bill would amend a 2007 anti-trafficking law that the Council resolution says does not go far enough.

The bill would remove the need for prosecutors to prove that underage victims of trafficking were coerced into prostitution; elevate penalties for patronizing underage prostitutes to the level of statutory rape; and require that anyone under 18 arrested for a prostitution offense be tried in family court rather than criminal court.