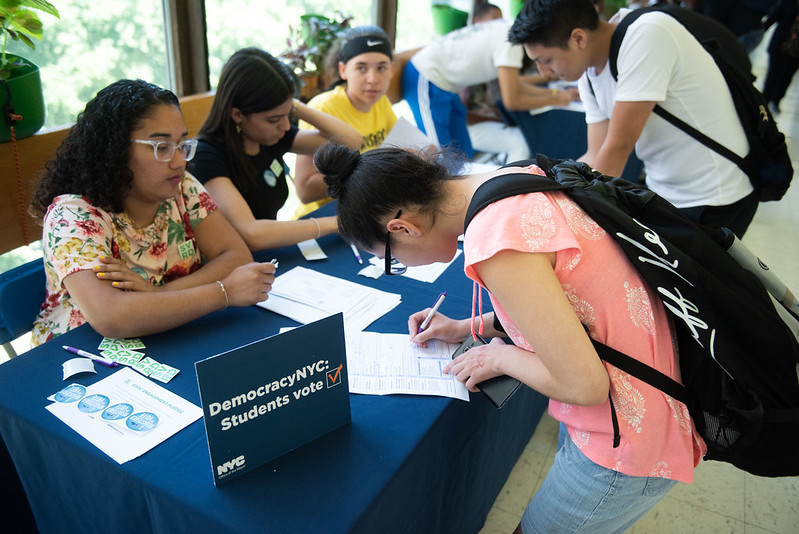

New York Launch of Online and Automatic Voter Registration Delayed Until at Least May

Students registering to vote (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

The state's new automatic voter registration system was meant to launch New Year's Day, but officials with the State Board of Elections claim emergency voting measures associated with the pandemic have forced the timeline back. The program is intertwined with an electronic registration system, meant to usher in widespread online voter registration, that is even further delayed – currently more than two years behind scheduled April 2021 launch.

State election administrators are now eyeing a May start date for online enrollment.

Sometime after that, the Department of Motor Vehicles will establish an automatic registration system, according to a spokesperson for the State Board of Elections who did not give a timetable.

The DMV is the first agency required by law to adopt automatic voter registration, or AVR, which will enroll eligible voters when they file personal information with what will be a series of participating agencies (unless the individual opts out). According to state law signed in December 2020, the DMV was supposed to launch on January 1 of this year, with a number of other participating agencies required to roll out the service beginning in 2024. That timeframe is still on track, according to the State Board of Elections.

“Unfortunately, due to unforeseen issues related to the pandemic, the plans for the rollout of both OVR and AVR have been impacted," wrote a State Board of Elections spokesperson in an email, referring to online voter registration and automatic voter registration and citing a number of laws and executive orders meant to limit the spread of COVID-19 at the ballot box.

"Many of those changes remained in place for the 2021 and 2022 elections and, as a result, required a reprioritization and refocusing of significant technical resources and staff time which would have otherwise been devoted to the implementation of Automatic and Online Voter Registration," the spokesperson wrote. "We are doing everything possible to ensure that appropriate measures are taken to expedite implementation of both Automatic and Online Voter Registration.”

A big sap of resources was the need – first under executive order and then temporarily under law – to rapidly create an accessible universal absentee balloting portal with the capacity to handle applications from virtually every active voter in the state. That took staff away from building the online voter registration and automatic voter registration systems, the spokesperson told Gotham Gazette.

The State Board of Elections had already blown the April 2021 deadline to stand up a fully electronic registration portal, blaming a hold placed on state funds by then-Governor Andrew Cuomo in the first months of the pandemic.

The board now has that money, $16.6 million, according to a spokesperson for Governor Kathy Hochul, who referred further inquiries to the board. The board is working with a vendor to build the internal system that transmits voter enrollment information to county election boards under both online and automatic voter registration. The State Board of Elections spokesperson said they could not release the vendor's name because the procurement process was not completed.

"These important electoral reforms are already behind schedule and need to be implemented as soon as possible," said State Senate Deputy Leader Michael Gianaris, a Queens Democrat who sponsored the automatic voter registration legislation in 2019, in a statement to Gotham Gazette. "I've made it clear to the Board of Elections that I will work with them to get this done soon and done right."

Under the law, participating agencies must integrate voter registration applications into applications for other services, which agencies will then transmit to county boards of elections. The idea is that as long as eligible voters are interacting with and providing their personal information to government agencies, they could also be automatically enrolled to vote. That would help boost registration rates, which have lagged. Individuals can opt out and agencies are prohibited from transmitting applications from people who are ineligible to register.

In the 2022 general election last fall 588,000 New Yorkers were eligible to vote but not registered, based on estimates of the vote-eligible population by the U.S. Elections Project, run by University of Florida political scientist Dr. Michael McDonald. Every year, New Yorkers who turn 18, gain citizenship, or are re-enfranchised post-incarceration become eligible to vote. Eligible teenagers will be automatically pre-registered under a recent state law that allows 16- and 17-year-olds to submit enrollment information in advance of their eighteenth birthdays.

Agencies are required to come to a rulemaking agreement with the State Board of Elections about how they will implement automatic voter registration, which is then subject to public comment. It is unclear if the DMV or other agencies have completed this process.

Under the law, the DMV's system must have an AVR system by the start of 2023. By January 1, 2024, the Department of Health; Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance; Department of Labor; Office of Vocational and Educational Services for Individuals with Disabilities; county and city departments of social services; New York City Housing Authority; and "any other agency designated by the governor" must all have AVR systems in place. SUNY must launch AVR by January 1, 2025.

Hochul's spokesperson said once the required agencies have implemented AVR the governor will evaluate whether to expand it to other agencies.

***

by Ethan Geringer-Sameth, reporter, Gotham Gazette

@GeringerSameth @GothamGazette

As Prosecutors Get Budget Boost, Public Defenders Seek More Funding Too

Mayor Adams and Governor Hochul (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

As Governor Kathy Hochul and Mayor Eric Adams, both first-term Democrats, double down this year on their focus on public safety and crime in New York, both have emphasized the need to give prosecutors and defense attorneys more resources to do their jobs. Both leaders have said the funding is necessary to abide by recent state criminal justice reforms and reduce court backlogs. But, while prosecutors across the state may soon be bolstered with more funding, public defenders say they aren’t aren’t receiving commensurate financial support from the two top Democrats.

New York State in recent years approved a series of criminal justice reforms to bail, discovery, and speedy trial statutes. As those reforms went into effect, the covid pandemic struck, impacting all aspects of the criminal justice system. Prosecutors and public defenders were already calling for additional resources to comply with the reforms, particularly the new discovery rules, while some officials – Hochul and Adams included – were faulting the changes for slowing down court cases at a time when crime was spiking in New York and nationally.

According to the latest data from the state’s Office of Court Administration, there is a backlog of 106,811 pending criminal cases across the state, up from 70,803 in 2022. Delays in the court system are one of the major factors in the increasing jail population, including in New York City. Data from the state Division of Criminal Justice Services shows that between January 2022 and January 2023, the average daily jail population statewide increased from 15,136 to 15,911, or about 5.1%; in New York City jails, the population increased from 5,344 to 5,821, about 8.9%.

Case delays also means that detainees spend longer in jail – in New York City, for instance, the average length of stay in a city jail has increased from 60 days in January 2021 to 108 days in December 2022. It is not easy to directly attribute the causes of the delays, but most experts and stakeholders agree that staffing at district attorney and public defender offices are a major factor.

In her executive budget released early this month, Hochul bemoaned the fact that the state’s criminal justice system was “absolutely paralyzed” by the pandemic. “And today, it's still clogged with backlogs denying justice to far too many,” she said, as she announced that the state would give court-appointed attorneys or public defenders their first raises in 20 years while also increasing funding for district attorneys (she’s also proposing more funding for reentry and alternative to incarceration programs, and further changes to the bail law).

Mayor Adams, in his 2023 State of the City speech, similarly said that ensuring speedy trials for defendants and justice for crime victims “means making sure our district attorneys and defenders have the resources they need to clear the backlog of cases and finding ways to expedite the discovery process.”

“Our legal system must ensure that dangerous people are kept off the streets, innocent people are not consumed by bureaucracy and victims can obtain resolutions,” he said. “This is something we can all agree on. Let's get it done in 2023.”

At a joint legislative hearing on the governor’s budget on Wednesday, Adams reiterated his point, saying, “our city’s district attorneys and public defenders are overwhelmed and need our help immediately. The state must make a major investment in them now or risk depriving defendants of their constitutional right to a speedy trial, delaying justice for victims and continuing the unprecedented level of attrition within each of these offices.”

District attorneys are funded largely by their respective counties, with supplemental state and federal grants. Public defenders, however, receive a much larger portion of their funding from the state and from localities. In New York City, the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice awards hundreds of millions in contracts for indigent defense funding.

Hochul’s and Adams’ budget plans show more focus on boosting prosecutors than public defenders, who play their own crucial role in the justice system, defending mostly low-income Black and Latino New Yorkers who cannot afford to hire private attorneys.

Funding for Prosecutors

The governor’s budget would increase “aid to prosecution” funding to $52 million in the next fiscal year starting April 1, up from $12.5 million in the budget that was adopted in April 2022. The funding would help all 62 counties across the state hire additional prosecutors and otherwise boost resources for district attorney offices. The budget, subject to negotiation with the Legislature, also maintains a $40 million pot of funding for prosecutors in the 57 counties outside of New York City to meet the requirements of the state’s discovery reform law, which took effect in 2020 and puts significant new responsibilities and tighter timelines on prosecutors.

A spokesperson for the state’s Division of Budget also said that an additional $7 million will be awarded to district attorney offices that create specialized units to shut down fentanyl supply chains and prosecute in cases of overdose deaths. “Distribution of these funds is pursuant to a plan submitted by the Commissioner of the Division of Criminal Justice Services and approved by the Director of the Budget,” the spokesperson said.

That is all welcome news to prosecutors, who have complained that discovery reform has been a heavy burden for overworked district attorney offices across the state, many of which have lost personnel in recent years.

“It's a welcome recognition by the governor that the burdens on the criminal justice system have changed dramatically, especially over the last three years or so,” said J. Anthony Jordan, president of the District Attorneys Association of the State of New York, in a phone interview. Last week, Jordan submitted written testimony at a joint budget hearing of the State Legislature on public protection, highlighting the need for more funding to help with staffing, training, new technology, and more as district attorney offices try to comply with the altered laws.

“The cost of compliance has fallen disproportionately on counties and so this is an important recognition by the governor that there is a significant role that the state must play in defraying these costs,” said Jordan, who is the DA of Washington County.

Jordan said that district attorney offices across the state have seen an exodus of experienced prosecutors, largely because of what they see as onerous discovery compliance requirements that have added to their workloads. DA offices have also not been immune to the trend of government employees departing to the private sector during the pandemic, in search of higher pay and more flexible work.

The discovery reform, he said, “relegated many trial attorneys to file clerks, and litigation that was not focused on guilt or innocence, but on paper chase. And that's more akin to practicing on Wall Street.”

A Manhattan Institute report released last month showed that prosecutors have been able to meet the discovery reform obligations within the mandated time frames in only 21% of cases – in local courts across the state, that rate is 16%, and in New York City local courts, that number falls to 13%. The report pointed out that, in New York City courts, dismissals increased from 44% of all disposed cases in 2019 to 69% in 2021; and statewide, dismissals increased by 14% in that period. In that same time, guilty pleas fell in New York City from 45% to 21%, and statewide, from 49% to 33%.

In the second annual judiciary survey on the implementation of the discovery law, released in December, 29% of judges in New York City reported that discovery obligations were met by the prosecution most of the time, compared with 79% of the judges outside New York City.

The numbers on discovery sanctions – including, but not limited to, dismissals, mistrials, and release under the state’s speedy trial statute – paint a complicated story, however. For instance, 62% of New York City judges said that the discovery legislation has greatly or moderately led to an increase in speedy trial release motions being granted, while 68% of judges outside of New York City said that the discovery reform has not caused an increase in these motions being granted. Mistrials were almost never granted.

In New York City, about 71% of judges said that the discovery law has led to slower case processing, compared with 30% of judges outside the city.

While fortifying prosecutors is essential, Jordan also agreed that public defenders should be given equal heft. “The justice system should be balanced,” he said. “The court should be funded properly, the institutional defenders, public defenders, they should be funded properly as should the prosecution. We are all performing state functions, just at the dollar of the county.”

“I would always rather litigate against a quality attorney because you're focused on the issues,” he added.

“Governor Hochul's Executive Budget makes transformative investments to make New York more affordable, more livable and safer, and she looks forward to working with the legislature on a final budget that meets the needs of all New Yorkers,” said Hazel Crampton-Hays, a spokesperson for the governor, in a statement.

In New York City, the mayor’s preliminary budget proposal for the 2024 fiscal year, which starts July 1, funds the city’s five district attorney offices at roughly the same level, or marginally lower, than the budget adopted last year for the current fiscal year.

Between the budget adopted last year and the preliminary budget proposal, the Manhattan DA’s funding is flat at $147 million, the Bronx DA’s funding is down by about $600,000, the Brooklyn DA’s funding is lower by about $408,000, the Queens DA’s funding is unchanged at $86.4 million, and the Staten Island DA’s funding is down about $639,000. The mayor’s office did not provide an explanation for the decreases.

Public Defenders Ask for More

Public defender organizations have already been struggling in recent years because of low pay and heavy workloads. In New York City, by June 2022, hundreds of staffers had quit the five public defender agencies that serve the city’s indigent population, according to The New York Times.

The governor’s state budget proposal includes $359 million for the Office of Indigent Legal Services, which assists counties and indigent legal service providers in the provision of services and monitors their implementation. This proposed budget remains unchanged from the enacted budget for the current fiscal year.

The governor’s budget also separately allocates $94 million (a $44 million increase) for the Office of Court Administration’s Attorney for Child Representation Program. That increase is meant to raise hourly wages for ‘18-B’ assigned counsel attorneys (private attorneys assigned by the court under Article 18-B of County Law) to $119 per hour for defenders in upstate counties and $158 per hour in downstate counties including New York City. Finally, Hochul’s budget plan includes $7.6 million for “aid to defense” programs that support defense organizations like the Legal Aid Society. That funding is also flat from this fiscal year.

But that may not be enough to support the needs of public defenders statewide. There are two separate issues at play – overall funding for public defenders such as Legal Aid Society, Brooklyn Defender Services, and others, and funding for 18-B assigned counsel programs, which involves private attorneys that are appointed by the court to defend indigent clients.

In testimony at the February 7 hearing, Patricia Warth, director of the state Office of Indigent Legal Services, said that the funding in the governor’s budget is inadequate, pointing to the office’s budget request of $382.8 million for indigent legal services for the 2024 fiscal year — about $23 million more than Hochul put in her plan. The largest discrepancy was in funding for family court representation – ILS requested $28 million while the governor proposed only $4.5 million.

“Without a significant state investment, attorneys are working under crushing caseloads without access to resources,” Warth said.

One of the main issues she noted is the need to increase wages across all indigent legal services for 18-B attorneys, who handle representation in roughly a third of cases, she said.

As Warth noted, increasing wages for 18-B attorneys is crucial to the implementation of the 2014 settlement in the Hurrell-Harring et al. v. State of New York case, which required the state to increase funding for mandated indigent defense in five counties – Ontario, Onondaga, Schuyler, Suffolk, and Washington. The state has since expanded the implementation of the settlement statewide through law.

Last year, the state appropriated $250 million for statewide implementation, which was part of the $359 million included in the governor’s new proposal – that increased investment has led to lower caseloads and higher average spending per case, according to Warth.

But, Warth noted, the state is already facing ongoing litigation over assigned counsel pay rates and the governor’s proposal to increase those rates is flawed. She said that it would both fail to resolve those lawsuits and likely lead to additional litigation. The state should fund the increase in rates instead of passing it on to counties and New York City, she said, and the state should not implement “case caps” on what an attorney can be paid for time on a case; hourly rates should be the same statewide; and there should be a mechanism for periodic rate increases.

“They are a vitally important part of the system and they haven't received an increase in rates since 2004,” she said. According to ILS estimates, the cost of raising pay rates would be between $150-180 million, based on pre-pandemic caseloads from 2019.

She also noted in her testimony that the last time 18-B attorney wages were increased in 2004, the state did not fund the increase, leading to counties cutting other public defense services to pay for it. “At the end of the day, funding public defense is a state obligation, and the state needs to pick up the tab for that obligation,” Warth said.

Mayor Adams also echoed that concern at Wednesday’s legislative budget hearing. He said the increase in 18-B attorney wages will cost the city at least $84 million starting in the current fiscal year. “Currently, we split this cost approximately evenly with the state, but, without state action, the city will be forced to cover the full cost of this increase,” he said.

State Senator Jamaal Bailey, a Bronx Democrat and chair of the Senate’s codes committee, has sponsored legislation for three years to increase pay rates for 18-B attorneys. “Equal access to justice is the foundation of our justice system. Underfunded and overburdened public defense systems not only erode quality of representation and public trust in the justice system, it upholds a two-tiered system of justice that can have grave consequences for New Yorkers who can least afford it,” he said in a statement to Gotham Gazette.

“Equitably funding public defense is fundamentally a matter of fairness – the individuals who continue to do this critical work cannot meet the needs of some of the most vulnerable in our society without adequate resources. It’s imperative that we shore up public defense funding to level the playing field and ensure that allocated resources sufficiently reflect changes in the industry and cost of living,” he added.

The call for more funding and changes to the proposal have been echoed by legal defense groups across the state.

“Gov. Kathy Hochul recognized the need for increased pay for assigned counsel in New York State. But her proposal calling for lower rates upstate relative to downstate is not equitable,” said Sherry Levin Wallach, president of the New York State Bar Association (NYSBA), in a statement. “Creating two separate geographic tiers of justice is unconscionable for the persons seeking access to justice and the lawyers that represent them.”

The NYSBA sued the state to implement a statewide pay rate of $164 an hour, on par with court-appointed attorneys in federal courts. “The current compensation structure is unworkable and results in a shortage of attorneys to take on this important work,” Wallach said. “Access to justice, which is fundamental to our democracy, depends on the ability of individuals to receive legal representation. It’s imperative that this long-standing injustice be fixed in this year’s final budget agreement.”

The New York City Bar Association has also included pay raises for 18-B attorneys on its state legislative agenda for this year.

The rates for 18-B attorneys are separate from pay for public defenders at service providers like the Legal Aid Society and Brooklyn Defender Services, which serve New York City and are funded largely by the state Office of Indigent Legal Services. Employees of those organizations are also facing tough times as their caseloads have ballooned and their wages have not kept pace.

“We are extremely disappointed that Governor Hochul failed to include any proposed allocation in her Fiscal Year 2024 budget for public defender and legal services organizations to address staffing and operational demands, instead prioritizing the needs of prosecutors and others in law enforcement,” said Legal Aid Society, in a statement after the governor’s budget was released. “Funding that favors one side of the legal system over all others reinforces bias and erodes efforts to further public safety.”

The mayor’s preliminary budget proposed about $126.6 million in contracts for Legal Aid Society (which cover indigent defense and other purposes as well), down from $192 million in the budget adopted last year for the current fiscal year. Overall, the budget proposes a $356 million allocation for indigent defense services. Both those numbers are expected to increase once the state budget is settled and the city has an idea of the amount of funding it will receive for indigent defense. For instance, last year, the city’s preliminary budget proposed $407 million for indigent defense, and later adopted a budget in June that allocated $434 million.

That nonetheless seems to suggest that the city’s contribution will be significantly lower than it was last year. Despite multiple requests from Gotham Gazette, which the mayor’s office acknowledged, City Hall did not provide any comment or clarity about the level of funding or why the budget proposes such a lower budget allocation despite the mayor’s own emphasis on funding prosecutors and public defenders.

Lisa Schreibersdorf, executive director of Brooklyn Defender Services, pointed to several other budget demands for the governor, above and beyond the budget requests made by ILS. Among those are cost-of-living-adjustments to the Office of Indigent Legal Services’ budget, increasing the funding by $10.6 million from $382.8 million to $393.4 million, which would help Brooklyn Defender Services increase pay for staff; an additional $4.9 million in “aid to defense” for a total of $12.5 million; and, chiefly, $127 million in funding to abide by the discovery reforms.

“The prosecutors and the defenders need the money, they all need the technology and they all need the staff,” Schreibersdorf said in a phone interview. “Because the amount of work that you're doing is roughly the same.”

She also noted that the churn of public defenders leaving their jobs because of increasing workloads only serves to delay court cases. “The mayor knows this story. The governor knows this story. This story is coming from the DAs and the defenders equally, and the cases cannot move to trial unless everybody is ready for trial,” she said.

Brooklyn Defender Services also called for $5 million for an indigent parole program, an additional $2.5 million for the New York State Defenders Association for a total of $3.58 million, and $1 million for a military veterans defense program.

Though Schreibersdorf said that indigent defense funding is a state obligation, she insisted that if the governor does not come through, the city should step in. “Somebody's gonna have to make it right,” she said.

“The City and State budgets are more than a list of numbers. They are a reflection of our values as New Yorkers,” said Justine Olderman, executive Director of the Bronx Defenders, in a statement to Gotham Gazette. “The draft budgets put forth by the Governor and Mayor, calling for rollbacks of bail reform and more money for police and prosecutors while massively underfunding public defenders and legal service providers, make a mockery of our standing as a national leader in social and racial justice. The Council and state Legislature must push back hard to ensure that these budgets help meet the needs and protect the rights of low-income Black and brown New Yorkers facing incarceration, deportation, family separation, and eviction.”

As Legal Aid Society calls for more state funding, it is under fire from its own members. Last week, more than 1,000 attorneys from the Association of Legal Aid Attorneys (ALAA), a union of public defenders, undertook a work stoppage amid contract negotiations with Legal Aid Society, a week after the union rejected an offer for a 2% salary increase.

The union noted that Legal Aid Society has sufficient funds to increase attorney salaries because attrition has created significant savings for the organization, and that it has increased compensation for managers while refusing a better contract for staff attorneys.

“Despite high caseloads and inadequate resources, members fight every day for justice for poor and low-income New Yorkers,” said Lisa Ohta, President of ALAA, in a statement last week. “Management tells us they appreciate our work, but appreciation doesn’t pay the bills. All staff deserve raises that address high inflation and attrition. We call on the Legal Aid Society to bargain fairly with ALAA so that staff can continue its vital work representing the most vulnerable New Yorkers.”

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

@samarkhurshid @GothamGazette

How New York Will Implement the $4.2 Billion Environmental Bond Act Passed by Voters in 2022

Projects underway (photo: Mike Groll/Governor's Office)

After voters overwhelmingly approved it last fall, state officials expect to issue the first bonds under the $4.2 billion Environmental Bond Act in the upcoming fiscal year, which begins April 1. It will take years to spend the entire sum, aimed at addressing some of the state's most dire climate and environmental needs.

The bond act authorizes the state to raise its general obligation debt to support public works in four broad categories: climate change mitigation, flood risk reduction, water quality improvement, and land conservation. Governor Kathy Hochul, state legislators, and environmentalists say the money is necessary to pay for critical infrastructure and to leverage other state and federal funding sources.

Hochul made it a central part of her climate platform in her first year-plus in office as she moves to implement policies to meet emission-reduction and renewable-energy mandates in the state's landmark 2019 Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, which will probably require bond act funds. The Democratic governor recently laid out her 2023 agenda with a major focus on environmental and climate policies that will in part be bolstered by bond act spending.

Before any of that can happen, though, the Hochul administration must set out the criteria and guidelines local governments and organizations will use to apply for grants for the myriad projects to be funded under the act, formally known as the Clean Water, Clean Air, and Green Jobs Environmental Bond Act.

The State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) is leading a working group of state agencies focused on developing procedures through a "robust engagement process…throughout the spring and summer," according to a DEC spokesperson. The groundwork they lay must then go through a public comment period before projects may be considered.

The state is expecting to finance $100 million in the next fiscal year, from April 2023 through March 2024, according to Hochul's financial plan. Its projection shows New York will spend less than a quarter of the total $4.2 billion over the next five years.

"We are moving as quickly as we can as a state enterprise to identify the current programs that exist, the ones that we are going to need to create new, and then developing the infrastructure behind that in order to stand those up," said Sean Mahar, DEC's Executive Deputy Commissioner, in a recent interview. "That's really our goal in the short term."

"Our staff and all the agency staff are excited about this and our sleeves are rolled up and we're at the table," Mahar said.

DEC and eight other state agencies make up the bond act working group: the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA), the Environmental Facilities Corporation, Department of State, Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation, the Adirondack Park Agency, Department of Transportation, Department of Agriculture and Markets, Office of General Services, and Homes and Community Renewal. While subcommittees are focused on each of the four spending categories, the exact structure of the office overseeing spending is still in development, according to DEC. So are other pieces of infrastructure, like a public facing website, which will help New Yorkers understand how the dollars are being spent.

"I'm personally of the belief that the governor should hire a director to oversee…and to help arbitrate where there may be some disagreements, as may happen from time to time between various agencies," said Julie Tighe, executive director of the New York League of Conservation Voters, in a recent interview. Tighe and NYLCV were major proponents of the bond act, and part of a coalition that urged voters to pass it when it appeared as question one on the ballot this past fall.

The bond act and its implementing legislation outline dollar figures for each of the four categories and describe a smattering of the types of environmental work they can fund. It requires the executive branch to lay out the technical details of how entities will apply for grants while ensuring 35% goes to "disadvantaged communities."

The legislation outlines an array of projects that may be eligible, including: shoreline restoration, fish hatchery and farmland protections, wastewater infrastructure and municipal stormwater projects, green building, pollution mitigation, and zero-emission school buses. The money comes with certain labor requirements, including a prevailing wage mandate, apprenticeship agreements, and Buy America provisions on iron and steel.

Amy Chester, managing director of Rebuild by Design, a policy and research group focused on resiliency and another member of the "Vote Yes for Clean Water and Jobs" coalition, echoed the importance of setting up the right groundwork early on. "I think the biggest immediate step is for the State to determine which agency(ies) will administer the different components of the bond act, and how they will ensure that there is the capacity to staff the programs effectively," Chester wrote by email.

Hochul's fiscal year 2024 executive budget proposes to add 131 full-time DEC employees specifically to implement the bond act, but its projects will be executed by a long list of state agencies and authorities, local governments, and others.

Chester, who was a senior policy advisor to Mayor Michael Bloomberg, also noted the importance of a requirement to spend a third of funds in underserved and disproportionately impacted communities. She is eager to see how they will "be involved in the prioritization and awarding" of grants, she said.

Short-Term Goals

According to DEC, in the short-term the working group is focused on engaging the municipalities, nonprofits, and corporations likely to be stewarding projects. The administration must then promulgate spending regulations including the form and content of grant applications, which will then be subject to public comment before taking effect.

"What we want to do is really have a robust stakeholder engagement process where we work across the state to galvanize good local conversations to get the right types of projects identified and prioritized," Mahar told Gotham Gazette. "And then work creatively throughout all the funding sources that we have available."

The bond act is one of many state funding mechanisms, along with the Environmental Protection Fund and others, that will be used for those projects, many of which will build toward the state's statutory conservation and resiliency goals. Hochul announced a number of those priorities in her executive budget, only some of which rely on bond act funds. Last year, Hochul advanced many climate priorities, including work on two major renewable energy transmission lines she greenlit and contracts are also moving ahead on offshore wind, solar farm, and many other projects.

"We don't have details of exactly what the governor and the department have in mind and so [on Tuesday, February 14] is a budget hearing at which we will ask for more details," said Assembly Member Deborah Glick, a Manhattan Democrat and chair of her chamber’s environmental conservation committee, in an interview. Glick is hoping to probe the administration's timeline and organizational structure for spending the bond act money. She also wants to know how the administration will issue grants, whether they will go through a competitive bidding process, and how it will ensure broad participation.

The broader funding itself will not be the subject of budget negotiations, however, as that was allocated in the current fiscal year budget, passed on the contingency that voters approved the bond act. "They have the money," Glick said.

According to a spokesperson for State Senator Pete Harckham, the Senate's environmental conservation chair and a Hudson Valley Democrat, the Legislature's real oversight functions will begin after DEC goes through the public comment period as part of its rule-drafting process.

"We need to be moving forward expeditiously but we also need to be moving forward smartly," said Tighe of New York League of Conservation Voters, who previously served as chief of staff at DEC. Part of that means ensuring local governments and nonprofits have the technical support needed to compete for grants and implement projects. That will be essential to meet the bond act requirement of dedicating 35% of funds to environmental justice, she said (she and other advocates want to see that figure hit at least 40%).

That could mean addressing environmental issues that have plagued low-income areas, like lead pipes in urban centers or harmful algal blooms in upstate lakes, though the legislation doesn't include specifics. According to the state's webpage on the bond act, the criteria will be the same being developed for the state's Climate Leadership and Community Protections Act (CLCPA) by the State Climate Justice Working Group, a body of regionally diverse public members and representatives from DEC, NYSERDA, and the departments of health and labor.

James Hanley, a fellow at The Empire Center, a think tank, wonders if the state will "actually manage to achieve that" benchmark. "Well-to-do communities tend to [be] more connected to power…We'll see how it actually plays out," he said in a recent interview.

"There are big governments like New York City, and sophisticated governments like Suffolk County and Westchester County, that have a lot of people who would be dedicated to this," Tighe said. That means the state will need to make additional efforts to facilitate "geographic diversity" in projects.

New York City is already angling for a substantial share of bond act funds. In December, the City Council passed a resolution calling on the state to allocate bond act funds to the city proportionate to its share of the state tax base (62% of state tax revenue and 43% of the population comes from New York City, according to the resolution).

Shovel-Ready Projects

In order to get money out the door, the state is looking to first fund ongoing and shovel-ready projects, according to DEC.

That includes school bus electrification already funded by NYSERDA and water supply and flood risk initiatives under the Water Quality Improvement Program and Water Infrastructure Improvement Act. The state may use the bond act to bolster land acquisition programs run by DEC and the Parks Department and backed by the Environmental Protection Fund, according to Mahar. Many of the current programs are funded under the federal Clean Water State Revolving Fund and state investments under the Clean Water Infrastructure Act.

Hochul is also putting billions of dollars toward the environment outside the bond act. Her $227 billion executive budget includes $500 million for the Water Infrastructure Improvement Act, $400 million for the Environmental Protection Fund, and $200 million for parks. Another $400 million will go toward lowering energy costs and retrofitting buildings. Other programs to increase recycling rates and local contaminant remediation are also included. And NYSERDA contracts and coordinates massive renewable energy projects that may or may not include significant state funding.

In her new agenda, Hochul also proposed a cap-and-invest program, to be run by DEC and NYSERDA, which would place a tax on carbon emissions and invest proceeds into energy rebates for New Yorkers. Over $1 billion from that revenue stream would be placed in a Climate Action Fund to support the rebates.

The executive budget also expands the New York Power Authority's jurisdiction to help meet renewable energy targets and includes a number of building decarbonization proposals.

The bond act places New York in a stronger position to apply for federal funding under the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. DEC Commissioner Basil Seggos praised the Inflation Reduction Act as a boon to the types of environmental projects the administration is eying. "The [Inflation Reduction] Act is a major boost for New York's leading climate efforts and will ensure all states and localities can help galvanize the clean energy economy," Seggos said in a statement in August. "New York is extraordinarily well positioned to fast track these initiatives that will reduce the costs and burdens on energy consumers, secure protections and opportunities for disadvantaged communities, provide inflation relief to Americans and New Yorkers, all while reducing the nation's deficit."

The demand is certainly there. A recent report from the nonprofit Environmental Advocates NY found that the Water Infrastructure Improvement Act gave $279 million to 73 projects while 246 shovel-ready projects valued at $665 million went unfunded in the last grant cycle.

According to Mahar, the exercise now is lining up bond act requirements with existing programs and "seeing what the gaps are."

The Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act

A number of Hochul's executive budget proposals – especially the cap-and-invest and renewable energy programs – will help New York meet the lofty energy goals set under the Climate Leadership and Community Protections Act, which then-Governor Andrew Cuomo signed into law in 2019.

It requires reducing carbon emissions 40% by 2030 and 85% by 2050 from 1990 levels. It also requires 70% of the state’s electricity to come from renewable sources by 2030 and 100% by 2040. In December, the Climate Action Council, a governing body established under the CLCPA, issued a scoping plan of recommendations to guide the state's work. Hochul’s agenda is in part based on those recommendations.

The bond act, particularly the largest funding category, up to $1.5 billion, for climate change mitigation, can support those goals, according to DEC.

"I think the way that we've approached our climate mitigation efforts is really all hands on deck when it comes to implementing the scoping plan," Mahar said.

The bond act "is intended to be linked to the CLCPA so that they are addressing the full range of concerns that are out there, whether it's water quality, coastline resiliency, and so forth," said Assemblymember Glick, "but we need to get more detail on their timeline and how they will choose organizations to actually do the work."

"All of our targets are very necessary but also very ambitious," she said. "And frankly they're goals, we may not meet them all in the time frame set out."

"Even if you could build out all the renewables in say six or seven years, which I think is going to be a struggle, you have to have all the transmission lines, you know, there are a lot of moving parts," Glick said. The bond act will help. So will federal assistance under the Inflation Reduction Act, she said, "but my sense is that people aren't working as hard and fast as they did before the pandemic so I think we have to pick up our game."

Financing the Bond Act

The bond act outlines how much can be financed for each of the four categories. The largest category, at $1.5 billion, is climate change mitigation, which can include anything from green buildings to renewable energy to pollution remediation.

Projects to mitigate flood risk, a growing problem with more frequent superstorms and eroding protections, will receive up to $1.1 billion. Water infrastructure and land conservation will each receive $650 million under the act, with another $300 million not specifically allocated.

A third of all funding must go to projects in underserved areas that have borne the brunt of pollution, climate change, and scarcity. The projects must have a useful life of ten years in order to be eligible for bonding.

Hochul and the State Legislature already allocated the full $4.2 billion to DEC in the current fiscal year, meaning the administration will not necessarily have to return to the Legislature to authorize the spending.

The capital plan in Hochul's new budget projects $805 million of the bond act will be financed over the next five fiscal years, through March 2028. That includes $5 million in the current fiscal year, growing to a projected $100 million in FY 2024, $150 million in FYs 2025 and 2026, and $200 million in FYs 2027 and 2028.

"$805M is currently the minimum amount of disbursements expected from the Bond Act for the period," wrote Jason Gough, a spokesperson for the governor, in an email to Gotham Gazette. That estimate is based on historic capital spending trends for similar, mostly reimbursement-based environmental and parks projects, he said.

While the first bonds are expected to be issued in the upcoming fiscal year (from April 2023 through March 2024), the full $4.2 billion will be financed over multiple years.

The State Comptroller’s office works with the Division of the Budget to monitor capital spending under the bond act to determine when to issue general obligation bonds to reimburse state coffers, according to a spokesperson for Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli. The office issues the bonds but does not have a role in determining which projects get awards, they said. Interest rates could impact state decisions on bond offerings, officials and advocates have said.

"Bond acts take years, if not decades to be spent out," DiNapoli told Gotham Gazette in a podcast interview in October, before voters approved it. "And because New York does have a high debt burden, this will be factored in before the state goes out to, you know, to borrow."

The bond act's debt service, paid through each year’s state budget, over the next five fiscal years is projected at $114 million with the first payment expected in fiscal year 2025. According to Gough, General Obligation Bonds are typically sold at the end of each fiscal year, meaning the debt service is not reflected until the following fiscal year.

The debt service is expected to rise to $354 million annually when all $4.2 billion has gone out the door.

"It's going to fund very important environmental initiatives, drinking water protection, wastewater management, open space preservation, and money targeted to deal with the climate issue, building and resilience helping us meet the very ambitious goals we have in New York State to deal with the issue of climate change," DiNapoli said in the October interview. "You need money to do this."

***

by Ethan Geringer-Sameth, reporter, Gotham Gazette

@GeringerSameth @GothamGazette