The Perks of Leadership: Who Got What in 2009

Domenic Recchia and David Weprin received the largest amounts of capital funding while Tony Avella and Mathieu Eugene garnered the least.

The chart accompanying this story did not include Councilmember Melissa Mark Viverito when first published. It was updated on July 14.

The city's "cultural czar" can now take his throne as the king of capital funding at the City Council.

More than $23 million of the council's capital items were solely sponsored by Councilmember Domenic Recchia, who chairs the Cultural Affairs Committee. Approximately $17.6 million of Recchia's funding goes to citywide or other cultural projects outside his Brooklyn district.

Unlike the council's discretionary expense funding for programs, which provides a minimum of $340,419 to each councilmember annually, the council's capital funding is doled out entirely at the discretion of the speaker's office. At nearly double the size of the council's discretionary expense funding, capital funding goes only to projects like renovations, building acquisition or new equipment. It is also a far more convoluted and complicated funding process with projects that span years and, sometimes, never even get started.

For a complete listing of who got what, click here

It also receives far less attention then the council's scandal-ridden discretionary expense funding, which has been the subject of several reform measures.

An analysis by Gotham Gazette of the City Council's capital and expense discretionary funding found the council's $505 million worth of capital funding for fiscal year 2009 is doled out with less equality -- capital king, Recchia, got more than 10 times as much funding as Councilmember Tony Avella, who placed at the bottom of our list.

Similar to its expense funding, members who chair influential or budget-oriented committees or have leadership positions are more likely to garner the bulk of city funding. While the distribution of funding can be based on need, some say it's really politics at play.

Distributing Dollars

As part of a transparency initiative from Council Speaker Christine Quinn, the City Council capital budget for the first time lists each project with the council members who sponsored it.

The capital budget contains more than 1,000 projects, most involving school construction or equipment acquisition, like technology upgrades or funding for a new auditorium or dance studio. A large portion of the funding goes to parks and public housing, such as security upgrades, as well as libraries. This year, about $140 million was allocated for projects in private buildings -- mostly to nonprofits looking to renovate or acquire new space (for more on that, click here).

The council's discretionary expense funding, which went through a far more stringent vetting process this year than ever before, goes almost solely to community groups and nonprofits for programs, not property or equipment. Under the council's latest reforms, groups most undergo more intense scrutiny from its finance department, the mayor's Office of Contract Services and register with the state attorney general's office.

The status of these reviews are available in a council budget document -- known as Schedule C. Every councilmember receives at least $151,714 in funding for programs under the Department of Youth and Community Development, $108,705 for programs within the Department for the Aging and another $80,000 to allocate as he or she sees fit.

For capital funding, council members typically create lists of potential projects in their districts, prioritize them and deliver their selections to the speaker's office for consideration.

A project's inclusion in the council budget does not guarantee it will be funded. Capital projects must undergo an intensive application process with the agency overseeing the construction or land acquisition. For example, a nonprofit looking to acquire space in Williamsburg for industrial use would need to get the OK from the council, and then work closely with the city's Economic Development Corporation, providing a step-by-step breakdown of the progress of the project. A nonprofit that receives capital funding does not get reimbursed from the city until the project is complete.

While the processes for getting capital and expense funding differ, some argue that council members use both types of funding to gain political clout in their districts and beyond.

Inside City Hall, some members and council insiders say funding is given out depending on a member's relationship with the speaker and as a political tactic.

Our Breakdown

As it did last year, Gotham Gazette has analyzed the council's expense funding and found that, similar to capital funding, members of the council's leadership are more likely to get cash than other members. We are now focused on capital funding, because this is the first time the council lists which member is responsible for what projects.

Our figures contain only individually sponsored items, so projects or programs that were funded by a borough delegation or more than one member were not included in our tallies. Therefore the analysis cannot be taken as the entire picture of capital or expense discretionary funding. Check out our full list here.

|

* Funding labeled speaker is allocated by the speaker, with advice from the council body, and given for larger, citywide initiatives.

Who Got What

Our top ten for capital funding includes the chair of the Cultural Affairs Committee, Recchia, the chair of the Finance Committee, David Weprin, the chair of the Public Housing Committee, Rosie Mendez, and the assistant majority leader, Lewis Fidler.

Clearly leadership helps when it comes to getting funding, whether it's capital or expense.

"I think there is a recognition of seniority and a recognition of council people in the leadership," said Councilmember James Vacca, who is serving his first term and received about $7.4 million of capital funding. "I don't consider that unfair. I think most legislative bodies do it based on leadership."

Others say the numbers can be deceiving. For instance, Recchia may have garnered the most amount of funding at $23.5 million, but nearly three-quarters of that goes beyond his Coney Island district. Recchia funds several groups based on Broadway -- a so-called condition of being the chair of the council's cultural committee.

Recchia did not return phone calls for comment on this story.

Councilmember David Weprin, who received the most expense funding last year according to our analysis, got more than $18 million worth of capital dollars. That sum, however, was bolstered considerably by a $12.5 million appropriation to the High Line -- an elevated park project in Chelsea miles from his Queens district.

This was not the case for others in our top 10.

Councilmember Larry Seabrook, whose expense and capital spending has been under scrutiny in the press, received $8.55 million in capital funding, all of which went to public housing projects or schools in his Bronx district. Seabrook did not return phone calls for comment.

On average, a councilmember received about $6.1 million in individual capital items.

And Why

Some, however, were far below that. Councilmember Charles Barron, who is often at odds with the speaker, received $2.27 million in capital dollars. Barron said his lack of funding could be attributed to his less than favorable relationship with the speaker's office.

"I'm not their favorite son," said Barron. "I speak out and speak my mind. When you do that you're not going to be up on the speaker's list."

Barron said he plans on introducing legislation this year that would mandate all members receive the same amount of discretionary dollars, including capital and expense funding, or that it's distributed by need. "It should be based on a formula on a needs basis. It should be the East New York's, the South Bronx, Brownsville," the councilman added, referring to the city's more impoverished areas.

Some of those areas did make our top 10 list, like East Harlem, which is within Inez Dickens' district and the Rockaways, James Sanders' district.

A council spokesperson said capital funding is not allocated by an exact formula, but is given out based on a number of circumstances, including need and the number of requests.

One's relationship with the speaker may not be the only reason why some acquire less discretionary funding than others.

Councilmember Daniel Garodnick is seen as a rising star at City Hall. He lands the so-called necessary endorsements, and his name is often floated as the next City Council speaker.

But when it comes to capital funding, he lost out.

Garodnick was fourth from the bottom in our capital funding analysis. Though some might say rightly so (he represents parts of the Upper East Side, which is the district with the highest median income). Garodnick said he was satisfied with what he received in discretionary funds.

"I thought we were able to satisfy the needs of the district with the funds we requested and the funds that were allocated," said Garodnick. "We wanted to recognize we were in tough budgetary times."

While he could not recall exactly, Garodnick said he received a sum of capital dollars close to what he initially requested -- unlike Barron, who said he received about a third of what he wanted.

Others attribute their ability to bring home the bacon with how well they do or don't do their jobs. Councilmember Lewis Fidler, also the council's assistant majority leader, received the most expense discretionary funding at $985,000, and snagged a considerable amount of capital too. Fidler said he gets a serious amount of expense funding because he chairs the Youth Services Committee, which oversees a lot of the programs in the city that would be eligible for these types of grants.

"I am on leadership because I'm an engaged legislator that advocates for the needs I believe in," said Fidler. "Which is also why I am able to put together a pot of properly vetted discretionary items."

Â

Forgotten Handshakes: The '09 Budget

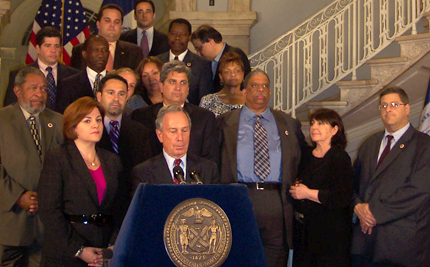

Photo by Courtney Gross

"We got screwed," said one advocate.

"We lost a lot of money," said another.

Those were not uncommon sentiments on the steps of City Hall Thursday night moments before Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Council Speaker Christine Quinn announced they had brokered a budget deal. As the sun descended four days before the beginning of the next fiscal year, some groups seemed to think their fiscal futures also were setting since the administration and City Council slashed funding for youth programs, senior centers and other services in an attempt to provide money for the city's classrooms.

"This is a question of setting priorities," said Bloomberg, who appeared particularly morose. "You can't say, 'All of the above.'"

Even though the City Council approved the budget late Sunday night, some advocates and council members continued to disagree with those priorities.

Many recognize the city faces tougher times. (Last week the Dow Jones reached historic lows for the month of June). But others argue a higher than expected surplus could have been stretched out to save community services. City officials, some advocates say, used overly pessimistic projections to cut programs prematurely. Others argue community services and programs should have been given priority over a $400 tax rebate and 7 percent property tax reduction.

Losers and Winners

An hour before midnight on Sunday -- the day before the June 30 deadline -- the City Council approved a $59.1 billion budget for fiscal year 2009 by a vote of 49 to 1 with Councilmember Charles Barron dissenting. The budget keeps spending virtually flat compared to fiscal year 2008.

It retains the $400 property tax rebate and 7 percent property tax reduction from the last year's budget. The council restored about $400 million to city agencies that the administration planned on cutting, officials said. Council members had initially hoped to restore approximately $700 million.

The city restored cuts to the Department of Education with $129 million from the City Council's discretionary funding. The budget added $18 million to the New York City Housing Authority -- about half the amount some had called for to stave off closing senior centers.

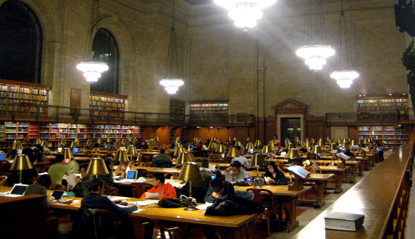

The budget also includes six-day library service, which was funded for the first time last year and put on the chopping block earlier during budget negotiations.

Overall spending increased 1.6 percent, which is below the rate of inflation. The City Council added 39 percent less to the final budget than it added in fiscal year 2008, and its own discretionary spending -- which has had its fair share of scrutiny and scandal lately -- was cut by 8 percent, said Quinn.

This year's budget announcement cited the principle of prudence. "It's a fiscally conservative, responsible budget," said Councilmember Vincent Ignizio from Staten Island.

It was also, council members said, one of the most difficult budget negotiations in recent memory, including stops and starts, impasses and frustration. “I would rather have three root canals,” said Councilmember John Liu last week regarding the negotiations.

A Questionable Surplus

Even though the budget was approved before the deadline of June 30, negotiations between the administration and the City Council sputtered partly because of disagreement on how much money there was to spend.

Historically, the Bloomberg administration tends to release conservative economic predictions.

"The mayor's job is to be more conservative," Councilmember David Weprin, chair of the council's Finance Committee, said early in the negotiation process. "The Office of Management and Budget is often very conservative with the hope that things get better. I don't think that's unusual."

In April, the council predicted the city would have $635 million more to work with than the mayor had projected. In May, the city's Independent Budget Office concluded the city would have a $4.6 billion surplus by the end of fiscal year 2008, after the mayor had warned for months of declining revenues.

On Sunday, Quinn said revenue forecasts are never a perfect science, and there was not a definitive explanation for why the council's revenue estimates were always higher than the mayor's.

Those estimates fueled the debate at City Hall. Council members pointed to them, arguing the city could afford to spend more on senior services, education and youth programs this year -- slashing services is not necessary yet, they argued.

The mayor, however, remained skeptical, which led to the cuts, some council members said.

"It went not to fat, not to muscle, but to bone," said Councilmember Lewis Fidler of the budget. Fidler stood with the mayor and speaker for Thursday evening's budget announcement, but he said he did so to show support for the speaker. He also voted for the budget on Sunday. "We were boxed in because the mayor was intransigent about spending $25 to $50 million of money that was there."

Filder, who suggested the city look at raising the hotel tax to boost revenue, continued to voice frustration over revenue projections up until the council's vote on Sunday, saying the administration intentionally kept estimates low to keep fiscal control out of the council's hands.

In a prepared statement, Councilmember Bill de Blasio voiced similar concerns over revenue projections: "I am disappointed that with a $4.5 billion surplus, the mayor forced the council to cut funding for essential services, including homeless prevention, legal and mental health services, and workforce development. In addition, the New York City Housing Authority, which is in dire financial straights, will be forced to shut senior centers and youth programs across the city. The mayor should not have put the city in this situation, and these cuts will be deeply felt for years to come."

For its part, the administration insists it is important to be prudent in these uncertain times. As a result, it put $2 billion aside for early debt payments in fiscal year 2010 and $350 million to pay expenses in fiscal year 2011. At the budget announcement, when asked why the city would not restore cuts in human services other than education, Bloomberg said the days of increased spending are over.

Quinn agreed. "We would have liked to have everything remain exactly as it was last year," she said. "That’s just not the reality of where we are financially for next year… As much good news there is in this budget, there is some bad news for some people," she added.

Saving Education and NYCHA

The good news will be heard in the city's classrooms. When the mayor and speaker said cuts would be kept out of science labs and English rooms, they got a round of applause.

For months, education advocates have blasted the administration for cutting more than $400 million from the Department of Education. They urged the city to "Keep the Promise" to children and fully fund the city's schools. Appeal letters filled mailboxes, and protests became a regularity on City Hall's steps.

Last week, one of those advocates, Geri Palast of the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, said the City Council -- not the administration -- had made the difference. "The City Council did an excellent job," said Palast. "The administration made cuts, and we were able to restore the money."

Several members had committed to voting against the budget if cuts to classrooms had not been restored, including de Blasio and the chairman of the Education Committee, Robert Jackson. Both voted for the budget on Sunday night, saying classrooms had been saved from the administration's ax.

The New York City Public Housing Authority did not do as well. Advocates and council members had been pulling for a restoration to keep the authority, mired in deficit, from closing its community centers and senior centers. While $18 million was appropriated in the budget, about half of the centers still will have to close, said the council's Minority Leader Jimmy Oddo.

The authority has 147 senior centers and 136 community centers. Advocates wanted $30 million to keep them all open.

Most council members emphasized on Sunday that it was the administration, not the City Council, that had proposed to cut spending (though they approved those cuts almost unanimously).

"The advocates and the public should recognize who cut and who restored," said Councilmember Inez Dickens of Manhattan.

Cuts Elsewhere

As opening statements were read at the council's Finance Committee meeting on Sunday, opposition to the slashed city funding was clear. A handful of advocates, who were escorted out by council security, chastised the committee for cutting funding for HIV and AIDS services.

They held up signs reading, "Say no to the City Council attack on people with AIDS." This is likely to be the first of what could be many protests over the city's spending cuts.

Other programs also will feel pain. City officials said about 2,000 summer jobs for youth will be lost, and the Department of Youth and Community Development will see an approximately 20 percent cut in its Beacon program, which puts community centers in public schools.

"This has been one of the most devastating budgets for community services that will have an impact on youth, immigrants and senior services in every community," said Susan Stamler, the policy and advocacy director of United Neighborhood Houses.

Some of these cuts led Barron, who is often at odds with the other side of City Hall and with the speaker, to vote against the budget in protest on Sunday. "Yeah, you put $129 million in for education," he said. "But look at what you did to infant mortality. Look at what you did to CUNY."

Funding for a council initiative to provide English language services and legal services to immigrants was slashed in half, said advocates, and infant mortality programs lost more than $1 million in funding. These cuts raised serious concern over how services will be affected across the city, said Jennifer March-Joly, the executive director of the Citizens Committee for Children.

March-Joly was one of a number of advocates who would have liked to see the administration and the council rescind its 7 percent property tax cut and $400 rebate to cover community services.

"The City Council and the mayor need to really focus on whether that should be done sooner rather than later," said March-Joly. "I think the magnitude of the things they can't restore will make it really difficult for the families that cant afford to go without."

Tough fiscal times, advocates said, are when these services are needed most. Given the cuts to senior and youth services, Councilmember Helen Foster questioned whether the council was too quick to pick education and classroom cuts as its priority.

"There are a lot of organizations and communities that are going to feel the pain of this budget," said Foster. "It would have been nice to spread it out more evenly," she added, referring to the council's support of different services.

An Open Window

While arguing families need the property tax cut and rebate to make it through the fiscal crises, Bloomberg did not rule out revisiting them in the future.

"When the adjustment appears not to be correct, better or worse, we have the ability to get together and change our plans," said Bloomberg. "We'll try to address it before we get into crisis mode."

There is no city regulation that prohibits the council or the mayor from raising property taxes or revising the budget later in the year -- if it comes down to that.

Some members hope the city will revisit the tax rebate as well as an increase to the hotel tax sooner rather then later. Councilmember Letitia James was the last member to offer general comments Sunday night, and she said just that.

"This surely falls on the shoulders of the richest man of the city of New York -- Mayor Michael Bloomberg," said James. Following that statement, there was a brief, practically melancholy, moment of silence in a normally buzzing chamber, roll call was called and the council approved the budget. Â

Juggling the Budget Surplus

The big fiscal news this spring is not any change in the forthcoming adopted budget for fiscal year 2009, beginning July 1. Nor is it the continuing investigations of the City Council's secret and perhaps illegal use of $4.7 million of its discretionary funds. The big news is how the mayor has already distributed the projected $6.5 billion surplus in the current fiscal year.

The use of that huge surplus shows off the genius of Mayor Michael Bloomberg's budgeting. The mayor has placated conservative fiscal monitors, he has pleased important constituencies with selective tax cuts, and he has kept the City Council out of important decisions.

One important tool for the mayor in all this has been his tight control of the budget surplus, which has precluded serious discussion about the short-term and long-term consequences of its uses. For instance, there's been little note of the fact that nearly $2 billion in reduced expenditures and services from January 2008 through June 2009 will pay for a large portion of over $2.5 billion in selective property tax rate cuts and rebates in 2008 and 2009 -- assuming the mayor does not abandon the proposed cut in the property tax rate for 2009. These cuts benefit commercial and residential property owners. Renters and the schools are among the biggest losers.

The picture of economic and fiscal gloom-and-doom laid out in the executive budget set out the rationale for the expense cuts - if not the tax cuts. But surpluses have become the norm in recent years, and with them, the mayor's discretion over the city budget has increased dramatically.

Last year's surplus, for instance, was nearly $6 billion. The two previous years' surpluses averaged over $3.6 billion. These surpluses represent significant shares of city-funded expenditures - this year more than 14 percent.

The Anatomy of Surpluses

Under state law, the city cannot end the fiscal year with a surplus. Instead, it must spend any extra monies before July 1.

This is where the mayor's discretionary power lies. As the city comptroller's May report on the executive budget points out, Bloomberg has already spread this year's $6.5 billion surplus over the next three years: $3.2 billion to pre-pay 2009 expenses, $3.0 billion to pre-pay 2010 expenses and $350 million to pre-pay 2011 expenses. The council must approve the pre-payments through a budget modification vote, but it has been reluctant to challenge these mayoral decisions.

Fiscal monitors admire Bloomberg's focus on balancing future budgets, at least in the short run. They particularly like the "conservative" revenue projections that have repeatedly under-estimated actual revenues in recent years.

On the other hand, the surpluses are mostly one-shot revenues each year - not guaranteed for the next year -- so using them dodges the problem of the city spending more than it brings in. The executive budget itself anticipates budget gaps in 2011 and 2012 that average $4.5 billion. The state comptroller in his June review of the mayor's financial plan for 2009 to 2012 estimates that the 2011 and 2012 gaps could average as much as $6.3 billion.

Creating the 2008 Surplus

How did we get to this point? The city comptroller's May report spells out where the projected $6.5 billion surplus in 2008 comes from:

- $2.6 billion from last year's (2007) surplus, set aside in what is called a Budget Stabilization Account (i.e., a reserve fund for surplus dollars);

- $2.5 billion more in revenues than the city projected last June;

- $1.4 billion in lower expenses than projected last June.

The mayor has already made an early payment of $2 billion to bring down debt service, which otherwise would have been due in 2010. So, by his figures, the current 2008 Budget Stabilization Account has $4.5 billion ($6.5 billion minus $2.0 billion). The city and state comptrollers include the $2.0 billion pre-payment and say the surplus is $6.5 billion.

Using the 2008 Surplus

The city comptroller also lists the uses of the 2008 surplus:

- $2.0 billion to pre-pay 2010 debt service;

- $3.1 billion to pre-pay 2009, 2010, and 2011 debt service;

- $500 million to pre-pay subsidies to city libraries and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority/Transit Authority;

- $400 million to pre-pay retiree health insurance;

- $546 million to the city Finance Authority for debt service.

This totals $6.5 billion.

The state comptroller's June report notes that without all the mayor's recent decisions -- rolling over the surpluses future tax increases and expense reductions -- the deficits for fiscal years 2009 to 2012 budget deficits would be, respectively, $4.9 billion, $6.6 billion, $7.6 billion, and $7.1 billion -- hardly a testament to "conservative" budgeting.

The Surplus Effects

One consequence of these pre-payments and grants -- as well as tax cuts -- is that the 2009 budget projects a $1.3 billion surplus for that year, much smaller than in recent years. 2010 has a tiny projected surplus of $350 million. The narrow focus of last-minute budget negotiations -- usually only $200 million to $300 million in changes - obscures the most important consequences of current surplus policy. The most stunning is the disconnect between the huge extra resources actually available in 2008 and the big cuts imposed during the same period.

The city comptroller's May report make this clear: Education funds, for instance (a mayoral priority), will be cut by $608 million from January 2008 to July 2009 and then by $753 million over the next two years, 2010 and 2011. That adds up to a $1.4 billion cut over three and a half years.

Compare education cuts with tax cuts. In Bloomberg's executive budget, the property tax rate cut averaging over $1 billion each year remains in place for the 2008 and 2009 fiscal years, along with the $400 rebate to house, co-op, and condo owners, at a cost of about $250 million in lost revenues each year. That adds up to over $2.5 billion in tax breaks over two years.

Last week the mayor indicated he might abandon the cut in the property tax rate in 2009, apparently because of the economic downturn and the cost of the city's recent contract settlement with police officers. However, the mayor has not committed himself to such a change, and some City Council members have indicated they would oppose any effort to eliminate the cut.

Neither the rate reduction nor the rebates have benefited renters, who represent two thirds of city households (and a substantial proportion of public school students).

Thus the $12 billion in surpluses recorded over the past two years have not so much encouraged a long-term conservative fiscal plan as created a political exercise in selective tax changes and, more recently, in service reductions.

Reforming Surplus Politics

The creation of rainy day fund would open more of these decisions to political debate. Under this plan, any surplus would go to a fund and be spent only under circumstances set by state legislation. That would limit late-year mayoral budget decisions to which the council seems to be only a rubber stamp. The council

made such a fund a priority in its response to the mayor's January preliminary budget. The city comptroller added his voice to that argument in his May report.

"Establishing a statutory rainy day fund would enable the city to manage its finances in a more transparent and straightforward fashion. The present method of applying surplus resources to future years is complicated, difficult for the public to understand and in some instances lacks flexibility that would allow resources to be applied where they are truly needed. ... The comptroller continues to urge the city to explore establishing such a fund," his report said.

Prospects for such a fund are dim in the short run. State legislation would be required, and the mayor would presumably try to block it. One way to move toward legislative action would be to make the creation of a rainy day fund a priority for any Charter Revision Commission the mayor might name in the near future. However, here again, the mayor controls the appointments and agenda of such a commission. Thus any reform may have to await debate among mayoral -- and City Council -- candidates in the 2009 election campaigns.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

Public Money, Private Property: The Council's Capital Budget

City Council members can also approve discretionary capital money,

including the public funding of private buildings.

including the public funding of private buildings.

Up two steps and through a discreet side door of an apartment building in Washington Heights, is a small, now-controversial non-profit group with a handful of employees and desks scattered with bilingual brochures.

The Upper Manhattan Council Assisting Neighbors, which claims to be one of a small number of groups in the area devoted to community service and economic revitalization, essentially is squeezed into three rooms, including one bathroom. The space is occupied by eight full-time employees and eight part-time workers -- some of whom were huddled around a chair readying a mail campaign on a recent morning.

But now, the council, otherwise known as UCAN, is looking not only to expand its programs, but also its digs. And they are doing it, in part, with tax dollars.

UCAN received a $2 million appropriation from the City Council last year to purchase and renovate a larger space that will host its offices, the area's only art gallery and a small theater, said the group's executive director, Hector Santana. While the group's relationship with Councilmember Miguel Martinez and the councilmember's sister, who recently resigned from the organization's board, has drawn extensive criticism, they claim their commitment to the community is a public service and worthy of public funding.

"The project will fulfill an unmet need," said Santana. "The city does what it has to do to ensure that dollars are spent appropriately."

Similar causes touted by other nonprofit groups have also caught the attention of the City Council.

Last year alone, the City Council appropriated nearly $160 million -- almost a third of its capital dollars -- to nonprofit or private groups that are looking to renovate, purchase or acquire not public property, but private. These line items, which were directed to more than 200 nonprofit groups in 2007, were allocated as the Bloomberg administration and the City Council committed to freezing capital funding for new projects. During that same time period, the administration and the City Council revisited rules outlining what groups could be eligible and what groups were ineligible for such funds.

While an extensive backlog and review by the Bloomberg administration and the City Council may mean that a lot of those projects may never come to fruition, the capital budget allocations represent a trend by the council to dole out taxpayer dollars to community organizations, just like it does with its expense budget. And like the council's discretionary funds, which members hand out for programs and initiatives and are the subject of two ongoing investigations, conflicts of interest and questionable connections between legislators and these groups continue to prevail -- especially because its capital budget is complicated and clandestine.

Needed Funding

Santana's Range Rover rumbled down Broadway in the Heights, making a straight shot to the group's prospective new location. Across from the lush Fort Tyron Park, a large, vacant building owned by Acadia Realty Trust, will house a New York Police Department precinct, offices for the city's Department of Housing, Preservation and Development, UCAN and more all in one building, Santana said.

The building curves around the intersection of Broadway and Sherman Avenue, and Santana points to a small storefront surrounded by bits of graffiti, which the group hopes to call home.

UCAN's project, which will include interior renovations to transform the area into a bustling community center, will cost about $5 million, which includes $2 million from the City Council and another $2 million from the administration, said Santana. If the project’s approval moves forward, the city will end up covering the majority of the project's cost.

Unlike the council's discretionary funds, which until recently received little scrutiny from the council, capital funding, both city officials and non-profit leaders say, gets a much closer examination. Even though UCAN's connections with Martinez have been questioned -- the group started receiving city money once the councilmember's sister joined the board in 2005 -- Santana argues receiving capital funding is a far more intense and arduous process. This, some say, would make it practically immune from the type of impropriety or corruption that recently mired the council's discretionary expense funds.

But that doesn’t mean capital dollars do not raise questions.

For years, the city has doled out dollars to non-profit groups for public facilities that are not public. The more than 200 projects earmarked in the council's fiscal year 2008 capital budget were labeled as "construction or acquisition of a non-city owned public betterment." Appropriations ranged from $22,000 for camera equipment to $3 million for new construction or building acquisition. (Capital funding is allocated specifically for property or equipment, and is not given out for programs or initiatives.)

While the council's estimated $500 million capital budget primarily goes to public housing, education or recreation facilities, approximately 30 percent of it was slated for buildings the city did not own, according to a review by Gotham Gazette.

Because the city froze funding for new non-profit projects in 2007 while it reviewed guidelines for this type of funding, there could have been even more of such projects in previous years when members faced fewer restrictions on how they could allocate the money .

Questions of Politics and Access

For years the council's member items -- expenses doled out for specific programs at a member's discretion -- have been released in a large document called Schedule C. While the council's capital budget is printed and given out the day the budget is passed, it is far more confusing and far less transparent. For example, you cannot receive an electronic copy of this inch-thick, 212-page document. Apparently, no one has one.

In last year’s council capital budget, informally known as ResoA, appropriations are unclear. For instance, one line item labeled “Education, Misc.” is not earmarked for any group. A council spokesperson said that $2.5 million there is for members to cover education projects’ shortfalls throughout the year. This appears similar to "holding codes" found in the council's expense budget, which included funding given to programs in the middle of the fiscal year . That practice came under question during the council's budget scandal earlier this year and has since been discontinued.

Other projects do not have descriptions at all, such as a $1 million earmark for the SAFE Foundation, a drug treatment and counseling center in Brooklyn. That allocation, an inquiry to the organization found, is for a building renovation.

Some of these projects have already been rescinded and found not eligible for funding, like $500,000 for Mosquito Spraying -- which was both the group name and description of an allocation.

Like the council’s expense budget, the capital budget also offers opportunities to curry favor with members’ communities – or dole out favors to friends, family or former staff.

Several organizations in the capital budget, including UCAN, have been targeted as groups with close ties to particular members.

In last year’s capital budget, LIBRE, a group run by Councilmember Hiram Monserrate’s former staff, was allocated $500,000 for a community center building. Allegations have linked LIBRE to the council member's campaign for State Senate. Elsewhere, the Northeast Bronx Redevelopment Corp., which has ties to Councilmember Larry Seabrook, was allocated $1.25 million for a “intergenerational center.” The Village Voice has reported that city officials froze funding for the group in 2006 because they couldn't figure out where the money was going. For years, the group operated at the same address where the councilman has his district office, according to the paper.

Beyond ties to the groups themselves, some council members said the city’s capital funding, like its expense funding, can be given out more generously to certain members who are in leadership positions, have seniority or are close to the City Council speaker.

Councilmember Vincent Gentile, who joined the body in 2003, received $4.15 million in capital funding for groups in his Bay Ridge district, compared to Councilmember John Liu, who is chairman of the Transportation Committee and received $6 million. Liu said he was always “competing” for more as well.

Some members refused to disclose how much funding they received last year for fear it would be less than what others may have received -- a so-called indication of their success or failure at bringing home the bacon for their districts. Several members said even they are not informed about the overall budget. Schedule C -- the tally of member items -- lists which council member requested what item. ResoA does not. Members know what projects are theirs, but have no clue what projects were funded by their colleagues, borough delegations or the speaker.

This year, though, that will change. Come June 30 – the deadline for a budget approval – names will appear next to individual projects in the capital budget, revealing who got what. A similar initiative was rolled out last year for the council’s discretionary expense items, and Councilmember David Weprin, chairman of the Finance Committee, was dubbed the "King of Pork".

Blocking the Funding

Before 2007, there were relatively few criteria for the distribution of capital funding to city nonprofits -- despite the large amount of money. As a result, just because a group received an appropriation in the council capital budget, did not guarantee it funding. In fact, groups, including UCAN, never see a dime until the project is done, the paperwork is signed and they receive a certificate of occupancy to move in.

That process, according to city officials, was, and may continue to be, arduous and complicated. Because few standards existed in the council, problems often arose when a city agency took over the contracting and approval of a project. According to a 2007 memorandum of understanding between the administration and the City Council, "significant legal questions" had emerged over the funding of such projects -- from religious affiliations to the feasibility of the proposal.

With all of this confusion and backlog, in May 2007 the city called it quits -- sort of. It froze the funding for new projects and drafted guidelines that would apply to any new capital funding allocation for a building not owned by the city. But that didn't stop the council from giving almost a third of its capital budget to these projects last year. The agreement between the administration and the council included exemptions for projects already in the works and for housing preservation, cultural institutions and projects for which there was a significant public need .

The Bloomberg administration and council staff created a task force to review the criteria for the funding of capital projects on private property, and it announced guidelines in March. The guidelines will take effect in the coming fiscal year.

The guidelines will try to weed out some of the legal issues cited by the Law Department, like questions of religious affiliation or the funding of private schools. Non-profits now will have to privately fund at least 50 percent of a project if the total cost exceeds $2 million, and they must already have a record of service with the city. Under the new agreement, City Council members, the city’s Office of Management and Budget, and the Law Department will all review projects to ensure their legitimacy.

The Backlog Begins

City officials say much of the scrutiny is justified.

"I think the paperwork involved is very onerous, but perhaps necessarily so to make sure that all the t’s are crossed and the I’s are dotted so that taxpayer money is going to the right purpose," said Liu.

Such oversight, some believe, can prevent the difficulties that have arisen over the member items. Corruption in the capital budget is "less likely because the agency looks in some detail at exactly what the public dollars are paying for," said Councilmember David Yassky. "I think part of the problem with the expense funding is the agencies that disperse the funds don’t look in any detail at the services that the funding is being used for."

Some nonprofits, though, have taken issue with the city's objections for their capital funding. Although they understand why oversight is necessary, they see the city as putting too many roadblocks in the way of worthy projects.

For example, a source said the Law Department has raised objections to funding organizations that house Alcoholics Anonymous meetings because the 12-step program includes giving oneself over to a higher being. This apparently raised the issue of city funds being used for religious purposes.

Some council members claim even small capital items, like a handicapped accessible van for a local senior center, get held up in the process, no matter how badly they are needed.

And sometimes, projects are just abandoned entirely. Councilmember Jimmy Vacca of the Bronx had requested and appropriated $1.5 million to the Northeast Bronx Senior Center last year for a new facility. Currently, Vacca said, the center is hosted in a church basement that is not handicap accessible. Now, Vacca said it is unlikely the project will ever go forward, because it would be on private property.

"Many times when council members seek to fund projects on non-city owned land it has become a bureaucratic situation that cannot be ironed out," said Vacca. "The roadblock is that the city is telling us they want capital money used on city owned land."

Every council member interviewed for this story said allocating capital funding for non-profit facilities was legitimate and served the city . Some, like Councilmember Simcha Felder, said they would like to see the city increase the funds. "It's about time the city woke up and smelled the coffee," Felder said. "It should be increased every year."

A Good Cause?

Small, poorly staffed institutions may have the most trouble navigating the bureaucratic system of capital funding.

At the other end of the specturm, the Kaufman Center, a music and arts oriented non-profit with two schools -- one public -- and a renowned theater has not run into roadblocks – at least yet.

As a dozen children circumnavigate hand-painted trees, singing and giggling as they prepare for a choral concert that evening, the Kaufman Center’s executive director, Lydia Kontos, wandered through its recently renovated space. She points to a piano and nearly floor to ceiling windows, where students, both public and private, practice their musical abilities.

The $15.5 million project received $1 million from the city for classroom and studio space. While it has not received the funding yet, the center is confident it will see the city’s contribution eventually.

"It would be foolish to say $1 million doesn’t matter,” said Kontos. “It’s not like our tongues are hanging out."

Smaller non-profits that received funding in the past, though, fear new regulations will hinder their abilities to acquire city help in the future. The East Williamsburg Valley Industrial Development Corp. received a $1.5 million appropriation last year to acquire industrial space and keep it for affordable manufacturing. In an area being taken over by luxury condominiums, the appropriation from Councilmembers Yassky and Diana Reyna would help keep jobs in the community, said executive director Leah Archibald.

Because the group is relatively small, Archibald said it is unlikely they will be able to repeat similar projects. They would not be able to finance 50 percent, she said.

The new criteria could, some nonprofit leaders say, detract from the initial purpose of funding these types of projects, which was to mobilize and energize smaller groups who needed public backing.

Under the new guidelines, the community center, theater and art gallery envisioned by UCAN would not meet city requirements for funding. The Kaufman's Center multi-million dollar renovation, though, still would.

A Better Budget Outlook...To Some

Game Illustrations by Alex Eben Meyer

For two weeks, advocates and organizations have flocked to City Hall's steps to make their final pleas for funding. Instead of debating what new initiatives or programs to fund, some officials in this time of morose economic predictions are simply trying to hold on to what they have.

Tough times call for tough choices, said several city commissioners this week. Not every program or nonprofit will see the same funding in 2009 as in 2008 (If you want to learn how to get a hold of city funding, try our new game: The Budget Maze).

"This wasn't a good year for new needs funding," said Department of Parks and Recreation Commissioner Adrian Benepe at a budget hearing on Thursday. "For every dollar we spend, there is probably $5 you could spend on additional projects."

Some experts, though, say this pessimism remains unwarranted. Last week, the city's Independent Budget Office came out with an analysis of the mayor's executive budget, which was more upbeat than predictions elsewhere.

Its conclusion: The fiscal picture is brighter than expected, at least in the near future. While the office recognizes budget deficits loom for 2011 and 2012, the city could come out of the next two years relatively unscathed.

Given that analysis, some groups may argue for spending increases, especially in education, or immunity from cuts for particular departments. Others warn that the city should tread carefully, given Wall Street's volatility and the approaching threat of job losses.

Rosier Revenues

Earlier this month, Mayor Michael Bloomberg revealed a plan for fiscal year 2009 that halted increases in city spending and cut about $1.3 billion. He called the economic forecasts "scary" and urged New Yorkers to pray for Wall Street's speedy recovery.

Now, the Independent Budget Office sees a slightly different economic forecast. Though its report predicts job losses at nearly 60,000 over the next year, it also sees $1.2 billion more in tax revenue than the administration's predictions for 2010 and a $4.6 billion budget surplus by this fiscal year's end.

This outlook may not be entirely optimistic when compared to recent years, but it is slightly more upbeat than the mayor's projections earlier this spring. "The mayor needs to be appropriately cautious, but with the benefit of a few more weeks of information, we put out projections that we think are as accurate as we can be," said Doug Turetsky of the Independent Budget Office.

The Independent Budget Office also came out with rosier revenue projections than the mayor's office following the release of the preliminary budget earlier this year. In its executive budget, the administration revised earlier predictions, increasing those revenue projections.

Caution is still key to some officials and watchdogs. As befits his reputation for "prudence," Bloomberg often releases gloomier than expected economic predictions that tend to brighten as the fiscal year moves forward. Whether a political tactic -- as some observers claim -- or an economic one, it can keep city spending tighter.

"The mayor's job is to be more conservative," said Councilmember David Weprin, who heads the Finance Committee. "The Office of Management and Budget is often very conservative with the hope that things get better. I don't think that's unusual."

The Process Moves On

Whether the administration's projection is overly pessimistic is not the only item up for debate. While the city's education funding has monopolized the spotlight (see related story) other areas of city funding have drawn the attention of some officials and advocates.

Weprin is particularly disappointed at the administration's failure to streamline funding for some City Council priorities, like education, the Administration for Children's Services, sanitation pickup in the outer boroughs and libraries. During good times, he added, the administration and the council had an agreement to end the budget dance -- a process where the mayor cuts funding with the expectation that the council will restore it. Now it seems that agreement is over.

"Frankly, it's a little disturbing, because these baseline items are not huge items in the overall budget," said Weprin. "We're back to the budget dance."

During a hearing on the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's capital budget, officials said the economic climate was forcing the authority to reevaluate its priorities, from subway station upgrades to major projects like the Second Avenue Subway, according to a press release from Councilmember John Liu.

Council members also have questioned the impact of program cuts, inlcuding those within the parks department, which is facing a decrease of $17.2 million from fiscal year 2008. That budget also did not restore the council's playground associates initiative, which funds full-time employees to oversee the city's playgrounds. Advocates and council members questioned whether this cut would threaten quality, maintenance and safety at the city's public parks.

"The city's parks, once the most celebrated and unprecedented public works program in the nation, have become dumping grounds and havens for drug use, prostitution, the homeless and criminal activity," said Geoffrey Croft, the president of NYC Park Advocates, in a prepared statement at Thursday's hearing. "Their maintenance and safety have plummeted under the weight of crippling budget cuts."

Despite recent cuts, said Benepe, the department's capital budget has doubled in the last five years.

The administration and the City Council have until the end of June to approve a budget agreement -- a proposal that now reaches toward $60 billion. That's 35 days and counting.

Â

Checking on How Government Spends Your Money

One of the first official responses to the New York City Council's use of phantom non-profit organizations in its budget process came from City Comptroller Bill Thompson. He sent a letter to Council Speaker Christine Quinn outlining a number of actions he will take. They included his own review of council discretionary funds and an independent audit of the council's discretionary fund budget process.

His stated aim: to "strengthen budget transparency and help restore trust and confidence to our city's residents." Others might see a political motive at work as well since both Quinn and Thompson are likely candidates for mayor in 2009.

The dubious budget process at the council had apparently gone on for some years, so it is natural to wonder why the comptroller's office -- or other city offices, including the mayor's -- failed to notice the problems first reported in New York Post and under investigation by the U.S. attorney. The scandal, then, is not simply embarrassing for the council, but raises fundamental questions about how well fiscal and managerial oversight works in this city.

What the Comptroller Does

The city comptroller's audit role is clear enough and his work is readily accessible on his Web site. His office provides two key summaries of its auditing work, a city-charter mandated yearly report, which gives an overview of audits during the previous fiscal year, and a convenient listing of all audits during the most recent calendar year.

There were 69 audits in calendar 2007 alone, and they reveal any number of financial and managerial problems: in mayoral agencies, at the City Council and in for-profit and non-profit agencies that receive funding or other assistance from the city. But a review, over time, of some of the issues raised by these audits makes it clear that while the comptroller's findings may identify problems, they do not necessarily solve them.

The annual report, in particular, shows how many audited public and private agencies apparently minimize or simply ignore the audit findings. The New York Yankees, for instance, have made a habit over more than 10 years of ignoring audits and repeatedly trying (unsuccessfully, thanks to the audits) to shortchange the city on their rent payments.

Auditing City Council

Interestingly, a September 2007 comptroller audit of City Council budget procedures anticipated some of the problems now generating such a furor. The audit of the City Council's $14.3 million other-than-personal service (OTPS), or non-personnel, expenditures, for instance, shows that the council "did not comply with the City Charter, [contracting] rules, comptroller directives..., and its own purchasing procedures when making OTPS purchases."

The council paid approximately $1.67 million for printing, almost all of which went to only five vendors. The charter and contract rules state that any purchases over $5,000 must be competitively bid, but the council broke up its purchases from the five vendors into units under the $5,000 threshold to circumvent the bidding rules. In a separate finding, the speaker's own Central Office violated its rules as well as city contracting rules in not obtaining bids on its own expenditures.

Monitoring the Executive Branch

The bulk of the comptroller's audits are focused mayoral agencies, through which most of the city's $60 billion budget flows. One of Thompson's most sweeping findings during his tenure covers several mayoral agencies (including parks, economic development, and Information Technology and Telecommunications) that manage franchise, concession, license, and lease agreements granted to private organizations. A recent summary audit notes, "Between January 1, 2002 [as Thompson took office] and June 30, 2006, the Audit Bureaus have completed 41 audits of [such] entities....These audits resulted in the assessment of [$23.8 million] in additional revenue due the city."

One of Thompson's first audits, released on May 30, 2002, went further back and reviewed the city's agreement with the New York Yankees, overseen by the parks department. During the four years, 1997 through 2000, the Yankees paid $18.8 million in rent to the city, but because they overstated rental credits (they can deduct these valid maintenance costs from the rent due the city) and underreported revenues, the Yankees owed the city $367,000.

Years later, the Yankees were still overstating their rent credits: over $1 million in 2002, and approximately $400,000 in each of calendar years 2004 and 2006. Invalid claims for credit for certain labor expenses showed up three times in 2007/2008 quarterly audits, even though they were specifically prohibited by the parks department in 1996. (From 1997 to 2000, the Yankees went so far as to not count as revenues -- although they already had the money -- "rain-check" tickets that were never redeemed when games were canceled and rescheduled.)

Overall, from fiscal years 2002 through 2007 the comptroller has conducted 578 audits and special reports that have generated a total of $211 million in actual and potential revenues and savings.

Correcting the Problems

A review of recent audits of other mayoral agencies shows some of the difficulties in getting agency managers to resolve identified problems. The audits also serve as a useful complement to the mayor's own management reports, which tend to focus more on lists of performance indicators than discussions of management issues.

For instance, the comptroller issued a report last summer on the Department of Youth and Community Development's monitoring of one of the council's favorite programs, the Beacon Centers, an after-school program. The June 2007 audit found that the agency "is not adequately providing oversight and monitoring of Beacon Program contractors." The program represented 13.5 percent of the youth department's approximately $307 million operating budget.

The problems at the department included weaknesses in program record-keeping, including measuring outcomes. The audit notes that in 2003, the department contracted with an outside vendor to "design an agency-wide outcome measurement and tracking program," but the contractor failed to perform and the contract was canceled. At the end of the auditing period, in 2006, the agency still had not adopted a system.

Auditors and Department of Education

The auditors' work is not without drama. Tussles with Department of Education staff provide an unusually vivid example of how difficult auditing can be. For instance, a June 2007, 54-page

audit of special education management found that the department "is not monitoring, tracking or documenting the provision of [special education] services in an effective manner, as shown by documentation that is incomplete, inaccurate or lacking altogether."

In all audits, the subject has the opportunity to respond to the initial findings. Education officials objected both to the auditors' methodology and their findings. For their part, the auditors said, "We strongly disagree with DOE officials' arguments about our methodology, which appear to be self serving and correspondingly misleading."

Auditors' prose tends to be dry and technical, but the education department's response apparently touched a nerve, because the audit report goes on: "DOE's methodology is a transparent attempt to reinvent this audit in terms that obscure DOE's inability to monitor and track the provision of services through a reliable and consistent system of documentation."

It continues: "It appears that DOE paid no attention to the numerous and various items of correspondence detailing our requests and communicating our audit results. We can only conclude that our expectation of DOE's good faith at the outset of the audit was misplaced."

A more recent audit of the department's operations, a March 2008 follow-up audit of expenditures within its Regional Operations Center for Regions 6 and 7, was less contested, but illustrates that even a follow-up doesn't resolve problems. The basic issues involved following rules on contracting and purchasing. The follow-up audit looked at how well seven recommendations in a May 2005 audit were carried out in fiscal year 2006.

The new audit determined that three recommendations were implemented, but that the other four were only partially implemented. Moreover, the audit identified three new issues, including the centers not following rules on certification of purchase deliveries. Then, further complicating resolution of the original issues, the audit notes that the regional offices were dismantled in July 2007, and oversight was transferred to another office.

The one other follow-up audit released this calendar year is a January 2008 report on Department of Homeless Services controls over computer equipment. A June 30, 2003, audit had found "widespread problems with [the department's] inventory controls over computer equipment. .... [It] could not account for $1,640,180 of the $1,841,015 in computer equipment purchases." Homeless Services countered that it had accounted for all but 325 purchases with a value of $333,003 by the end of that initial audit.

The follow-up audit acknowledged the department had implemented two of three recommendations but also noted that "major weaknesses still exist in DHS inventory-management process. Moreover, the inventory management procedures do not fully address Department of Investigation inventory standards." In addition, the audit found several new problems in the implementation of a software package purchased in 2002 to automate the computer inventory process, including a failure to use the system "to its fullest capacity."

How Better to Monitor the Money

The comptroller's audit function is invaluable in preserving the city's fiscal integrity, but even a short review of recent audits makes it clear that more oversight of the city's budget process is needed. A case could certainly be made for expanding the comptroller's auditing staff. But the mayor and council could also do much more.

A case could also be made for a charter review of the roles played by all the actors in the budget process. In a city with such a powerful mayor, the most important countervailing institution on fiscal integrity -- the comptroller -- has limited powers. The audits demonstrate that the comptroller works in a political as much as a fiscal world. Mayoral agencies and council offices are not always cooperative. Audit findings do not necessarily bring about change. Friction exists between the auditors and the agencies they review.

City Councilmember David Yassky, who hopes to replace the term-limited Thompson in 2010, in fact, said in an April 29

New York Post op-ed on the council funds scandal that he had "often felt there is an unspoken bargain between Mayor Bloomberg and the council: We get complete discretion to allocate some $100 million worth of 'earmarks'; in return, the rest of the mayor's $59 billion budget sails through without significant changes."

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

The 2009 Budget: Drawing the Battle Lines

The mayor's 2009 executive budget holds spending steady for the first time in five years, and at least 12 city agencies are seeing their spending slashed to varying degrees (this graph was created by Gotham Gazette from figures in the mayor's Fiscal Year 2009 Executive Budget).

Say sayonara to superfluous city spending, adieu to rosy revenue projections and farewell to fat city coffers.

For the first time since 2002, Mayor Michael Bloomberg's executive budget slams the brakes on agency expenditures -- ending the spending increases of the last five years. At the same time, Bloomberg has tentatively agreed to keep the 7 percent property tax reduction for one more year and continue the $400 tax rebate indefinitely.

At City Hall on Thursday, the mayor -- dressed in a crisp blue suit and red tie -- pointed to the slips and slides of Wall Street and to gloomy economic forecasts. Those predictions, the mayor contends, cannot be ignored.

"The numbers are scary," Bloomberg said during a presentation that kicks off his formal budget negotiations with the City Council. "Wall Street, which we depend on for tax revenues, is having some serious problems."

Those problems affect city agencies, and now the mayor is proposing to slash 6.4 percent of city funded expenses in fiscal year 2009. What started as a so-called across the board cut -- which the mayor first announced last year -- is beginning to play favorites, with certain agencies and programs, like the city's Department of Youth and Community Development, slated for more cuts than a few other areas, like the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications, which is getting an increase in city funding.

The largest proposed cuts come in programs that are key City Council priorities.

Though these decreases are not definite -- the City Council and the administration must reach an agreement and pass a balanced budget by July -- you can bet this latest budget battle will be far less congenial than those of recent years.

While much of the growth in city spending is grinding to a halt in the 2009 executive budget, some departments have fared better than others. At least nine agencies could see an increase in spending from fiscal year 2008 (This graph was created by Gotham Gazette from figures in the mayor's Fiscal Year 2009 Executive Budget).

An Overview

On Thursday, the mayor proposed a $59.1 billion budget -- a small increase from his $58.5 billion proposal released in January. The budget includes $1.3 billion in cuts for fiscal year 2009, which starts in July.

Higher than expected revenues and a 33 percent increase in foreign tourists since 2000 have provided some cushion for the city. But, according to Bloomberg, our fiscal horizons remain cloudy. For fiscal year 2010, the mayor said he expects a deficit of $1.3 billion, growing to $4.6 billion in fiscal year 2011.

Because of that, the administration plans to roll back the 7 percent tax break, passed in 2007, to raise $1.22 billion -- but not until fiscal year 2010. (Some officials see that proposal as a stretch, since next year is an election year, and politicians dislike raising taxes the year their name is on the ballot).

One official said it was not impossible, though unlikely, that the City Council would revisit the tax rate this year, depending on the economy.

"Obviously if we needed revenue we could raise the property tax by a percent or two," said the council's Finance Committee Chairman David Weprin. "The sense of the council is everyone would like to see the property tax stay in place for the most part."

In what many have termed a significant but needed cut, the mayor also proposed to extend the city's four-year capital plan to five years, effectively slashing 20 percent of the program's cost by extending proposals -- not eliminating them. The administration has not determined which projects will be pushed back and plans to release that information in September.

For the most part, the city's fiscal watchdogs saw the mayor's proposal as sound -- a realistic approach to a teetering stock market and an economy that, some analysts say, is ensnared in a recession. But critics have already emerged and are gearing up for a contentious battle over some of Bloomberg's planned cuts, particularly in education.

Wall Street Pains

While tourism continues to boost revenues, Wall Street's woes have barreled down Broadway and into City Hall. Wall Street firms lost more than $11 billion in 2007, after posting record profits the previous year, according to the mayor's office.

Because Wall Street drives the city's economy (wages in the securities industry alone account for 25 percent of city salaries), any volatility there can threaten city programs.

Much of his hour-long budget presentation was devoted to the financial sector's impact on the New York City economy. In slide after slide, the mayor reiterated Wall Street's influence, despite efforts to diversify city revenue.

"Everyone in this city should pray that Wall Street does well," said Bloomberg gesturing to a slide with his presentation's typically morose statistics.

The city's fiscal watchdogs and observers have echoed that sentiment. While little can be done about the impacts of this economic slowdown, some experts suggested the administration should attempt to limit Wall Street's impact in the future.

Nicole Gelinas, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, said the city should explore other sources of revenue, so it is not held hostage to the ebb and flow of the stock market. "A lot of this is designed on our tax structure," said Gelinas. "We could make this a lot easier if we designed a structure that attracts new businesses."

Where the Cuts Run Deep

A pillar of the Bloomberg's fiscal year 2009 budget is that no one is immune -- all city agencies must shoulder the burden of hard times, which some see as a fair approach to fiscal policy.

"From a fairness point of view, you don’t want to have any sacred cows," said Charles Brecher, executive vice president and director of research at the Citizens Budget Commission. "Everyone has to pitch in."

Although Bloomberg directed all agencies to submit approximately 3 percent cuts last year and another 5 percent for fiscal year 2009, some departments are now bearing more of the burden than others.

According to an analysis of budget documents, several agencies are seeing more than 10 percent cuts in city spending. The Department of Youth and Community Development has a 27.6 percent decrease in city spending for fiscal year 2009 compared to the projected city spending in fiscal year 2008. The Department for the Aging, Department of Cultural Affairs, Department of Homeless Services and Housing Preservation and Development are all slated for large cuts in city spending -- ranging from about 11 to 19 percent.

"Any further cuts to the Department of Aging, is serous business in my backyard," said Councilmember Vincent Gentile.

Other departments have been spared. The Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications is seeing a 20 percent increase in city funding, catapulting their funds from $202 million to $243.7 million. The increase, according to the mayor's executive budget, will go to the city's new wireless network for emergency personnel and to support the city's 311 information hotline.

Some of the rising costs, however, are out of the administration's control. For instance, the Department of Sanitation's expenditures have risen by 2 percent from 2008, which, according to budget documents, are attributed to the rising personnel and waste export costs.

Overall, some of the agencies that see large decreases in city funding may have gotten a boost in funding from the state or from Washington. Others, like the Department of Youth and Community Development, saw their federal funding actually decrease as well.

City Council tends to put a high priority on spending for community-based groups and programs that tend to get funding from the city's youth department and other departments slated for spending cuts, such as the Department of Cultural Affairs, which is facing an 11 percent cut in city spending. In the past when such programs have been cut by the administration, the council has restored their funding during budget negotiations -- a process called the budget dance. Some observers have crticized this maneuver, saying the executive branch's reductions are meaningless, since they are always restored, allowing council members to score easy political points .

"We've come a long way to ending the budget dance," said Weprin, alluding to the back and forth between the administration and the council. "It always seems to be that when there are cuts, council priorities seem to go first."

Battle Lines Drawn

One priority close to the Bloomberg administration, education, has been thrust to the budget debate's center stage. A coalition of more than 40 organizations, including the city's powerful teachers union, already is preparing to launch a publicity campaign slamming the administration for backing down on its promise to fund education.

While the city's education funding is actually up from fiscal year 2008, by about 3.5 percent, advocates contend higher costs for food, energy and the overall impact of inflation mean the Department of Education and classrooms will end up losing out. In this year's state budget, education funding saw a 7 percent increase compared to the last fiscal year.

On the steps of City Hall on Wednesday, the day before Bloomberg released his executive budget, city officials and advocates railed against the mayor -- urging him to "keep the promise" of continuing to increase education funding.

"Turn this car around," said Robert Jackson, chair of the council's Education Committee, who pledged to vote against the budget if the department's funding was not restored. "You're heading in the wrong direction. You're supposed to be the education mayor," he added, alluding to Bloomberg's takeover of the public schools.

Following the release of the mayor's budget, Council Speaker Christine Quinn called the total budget proposal responsible, but hesitated to lend her full support because of the proposed funding to the education department. "While the news of continued relief for homeowners is a positive step, the cuts to a number of city agencies, most notably to the Department of Education, are a cause for concern," she said in a prepared statement. "The council remains committed to ensuring that the necessary cuts have the least possible impact on our classrooms."

It is likely the Department of Education will not be the only battleground at City Hall this fiscal year. Libraries, which have often been the focus of the City Council and the administration's budget dance, are making an encore appearance on the dance floor.

Though the budget shows a 70 percent decline in city funding for the city's library system, funds have been prepaid to keep services up for fiscal years 2008 and 2009. But cuts elsewhere, like to the nearly $50 million needed to keep branches open six days a week, are being cited by some members as a priority.

"Sixty percent of the money added last year for six day service would be eliminated, which would in effect destroy six-day service," said Gentile, who chairs the council's subcommittee on libraries.

Other areas identified as council priorities, like the Quinn's suggested tax rebate for renters or her proposal for a sales tax free week, were left out of the mayor's budget. So far, the council's suggestions to cut spending in the administrative offices of the Department of Education and out of the classroom have not seen a response from the administration.

As the Economy Worsens: Helping People Find Jobs

Photo (cc) Becky McCray

As Wall Street does tailspins and foreclosure signs spring up across town, New York City's labor market can seem daunting to all but the best connected. Somehow, though, amid the economic tumult, the city government is helping thousands of New Yorkers find jobs.

That unlikely trend is a product of the workforce-development system, a network of occupational training and counseling services that has historically been seen more as a welfare institution rather than an economic force.

Since 2003, the Bloomberg administration's Department of Small Business Services has sought to transform the system, one of the nation's largest, into a market-based employment network with broad-based training and hiring programs. Under the ambitious restructuring effort, job placements per quarter have grown from about 130 in mid-2004 to some 4,300 by late 2007.

Yet some workforce experts warn that the improvements have not erased structural issues -- from entrenched poverty to limited education to language barriers -- that keep many people out of work. As the system tries to promote job opportunity in underserved communities, it must contend with a dwindling budget and a strained social service system. Reflecting a nationwide trend, the state's workforce programs lost about $130 million in combined federal and state funds between the 2003-2004 and 2005-2006 program years, according to an analysis by the New York Association of Training and Employment Professionals and the New York-based think-tank Center for an Urban Future.

More fundamentally, the system faces the challenge of promoting economic equity while encouraging business growth. Julian Alssid, executive director of the Workforce Strategy Center, an organization that has worked in 22 states to revamp workforce-investment programs, said workforce development should straddle social responsibility and economic interests. "You kind of need to balance the two," he said. "The whole idea of this is you're both getting people out of poverty and growing the economy."

Unemployed in New York