Queens Groups Are Divided Over District Lines

With the preliminary redistricting maps to be announced next week, tensions are rising in Queens, where communities are split along legislative lines and rival plans to redraw them.

Many Asian-American groups, joined by some Latinos, have pushed for State Senate and Assembly borders to be redrawn around a single, cohesive Asian community which would cut across Queens and Nassau county lines. Others, led by the group Eastern Queens United, have categorically opposed this.

The groups’ main argument centers around what constitutes “communities of interest” and whether or not race and ethnicity is a key factor in determining these. Moreover, politicians and analysts have said that grouping voters from the two counties together will give Republicans an edge. Both sides have distanced themselves from party considerations.

“We were able to meet with numerous groups throughout the city and develop community boundary lines and narratives to accompany them,” said Jerry Vattamala, a staff attorney with the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF).

Asian-Americans are a growing population in New York. Over the past ten years, the number of Asians in New York City has risen from about 1 million to about 1.42 million, growing from 5.5 percent to 7.3 percent of the total New York population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Over 500,000 Asian Americans live in Queens.

The influx came mostly from immigration, according to James Hong, the Civic Participation Coordinator at MinKwon Center for Community Action, a Korean group. He said that many Asian-Americans who live in these areas have common interests, especially with regard to immigration law, language accommodations and socioeconomic concerns.

Despite their growing numbers, Asian voters are under-represented because their communities sit on top of many legislative partitions, according to AALDEF. Asian communities in Richmond Hill and Elmhurst are split into as many as six assembly segments, said Vattamala.

The current lines “absolutely split up Asian-American Communities,” said Hong. “The effect of diluting the Asian Vote has been very significant.”

In July 2011, 14 Asian-American groups including AALDEF and MinKwon have teamed up to form the Asian-American Community Coalition on Redistricting and Democracy (ACCORD), which has endorsed a proposed redistricting plan called “Unity map." The map was created by AALDEF, PRLDEF (Latino Justice group), the National Institute for Latino Policy and the Center for Law and Social Justice of Medgar Evers college. It was submitted it to the state’s legislative task force on redistricting.

But many other residents and politicians of Queens are opposed to the Unity plan, saying that it doesn’t make sense to put residents of Queens and Long Island in a single Assembly or Senate district. Eastern Queens United, which includes civic groups from Glen Oaks, Floral Park, New Hyde Park, Bellerose and Queens Village, said that the common interest of Queens communities far outweighs any common interests along ethnic lines.

“This is unacceptable,” said Bob Friedrich, the President of Glen Oaks Village Cooperative. “We don’t wan to divide these communities along ethnic, color or religious lines. It serves the needs of politicians to divide these communities.”

Eastern Queens United held a community meeting last week, discussing the redistricting. Assemblyman David Weprin and State Senator Tony Avella attended the meeting, with Avella pledging to vote against any plan, which cuts legislative districts across county lines.

“I understand the goal and agree with it but the way they’ve gone about it is not only inappropriate, it’s reverse gerrymandering,” said Avella, who has met with ACCORD and criticized its proposals. He said that the coalition’s proposals have only gotten worse since they were initially proposed and that they would give Republican legislators an unfair edge in Queens.

He added that as of October 12, ACCORD admitted to failing to consult with South Asian groups whose interests might be different than those of Chinese and Korean Americans. MinKwon’s Hong denied this claim, saying that ACCORD had met with many South Asian groups, including Taking Our Seat as early as July 11.

Still, many lawmakers and analysts think that combining sections of Queens and Nassau Counties would benefit Republicans because of the large number of conservative voters that live in Nassau. Arthur “Jerry” Kremer, a lobbyist and former Assemblyman said that there are no communities of interest that cross county lines that “it is not uncommon for minority legislators to find that their districts are cut up and combined with others.” He added, however, that significant change in Nassau County is likely this time around.

Both ACCORD and Eastern Queens United have denied that their proposals had to do with partisan considerations. Spokespeople for each have said that their primary interest is keeping communities together.

Senator Martin Malave Dilan said that the likeliest areas to see change in the coming redistricting process are in Queens/Nassau, Hudson Valley and the Saratoga area. However, Dean Skelos, the Republican Senate Majority Leader, said that the 63rd senate district will not be in Long Island. Eastern Queens United’s Bob Friedrich said that this was a good start while ACCORD offered no comment.

A previsous version of this article incorrectly named ACCORD as the author of The Unity Map.

Common Cause Helps the Public Get Involved in Redistricting

This week a number of Assembly Democrats got a peek at what their new district lines will look like if the Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment has anything to say about it. And LATFOR, with legislative leaders, has for decades had the final word on drawing district lines for the state. The process of redistricting was conducted in secret, lines were drawn to protect incumbents and maintain the senate Republicans’ majority, legislators were consulted on what would be convenient for them. The people were as far away from the process as possible.

Even when their plans were challenged in the court as politically motivated or inherently in violation of the law, LATFOR and the majority leaders came out on top.

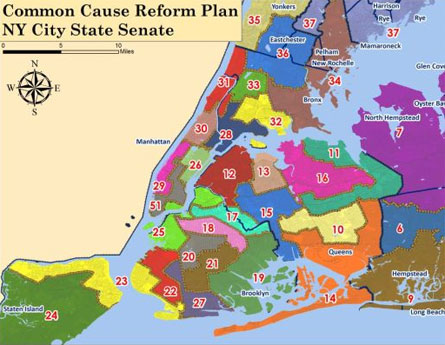

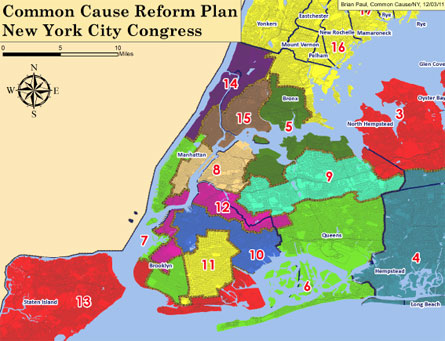

But this time things have changed. Thanks to the internet, the process by which legislative districts are carved up is no longer such a mystery. Mapping technology allows any citizen with a computer, some spare time and the proper information to draw up their own set of maps. Earlier this week Common Cause issued their own lines and teamed up with Newsday to present the public with an interactive mapping tool so that they can try it themselves.

"We have been outspoken about the problems with the current process, which is characterized by partisanship and political self-interest," said Common Cause’s executive director, Susan Lerner, during a conference call with the press. "Our goal has been to show that there is no practical impediment—it’s only a political one—to achieving fair, non-politicized district maps."

Looking for Input

"It is kind of like pulling back the curtain,"said Sen. Liz Krueger, who has been looking forward to seeing Common Cause’s lines for months. She apparently wasn’t the only one.

Assemblyman Jack McEneny, Democratic chair of LATFOR, said that he and his colleagues have been waiting to see what Common Cause produced, and the plan is to utilize parts of their maps.

"We have been anticipating them for some time," said McEneny. "We will take a look at them and see what good parts we can incorporate into our plan. Then I would expect we will begin to have public hearings in January."

As for what it feels like to have the public breathing down his neck while he is doing a job that used to be draped in secrecy, McEneny said, "Things have changed. It is part of democracy to be second guessed. We grow up thinking things are either good or bad, but there is a lot of gray here, a lot of competing interests and groups who value certain things over others."

The Power of Politics

Although they are happy to see the public given a chance to be more informed and involved in the redistricting process, members of other good government groups are skeptical that Common Cause’s efforts will change the end result.

"I think they (Common Cause) looked at lines in a non-partisan manner, and that is refreshing. It looks to me that they managed to keep communities of interest together without regard to incumbents, and that is refreshing. But I don’t think it will make a darn bit of difference. I don’t think LATFOR has regards for anything but incumbency protection," said Barbara Bartoletti of the League of Women Voters.

Dick Dadey, executive director of Citizens Union (Gotham Gazette is published by Citizens Union Foundation, the sister organization to Citizens Union), agreed with Bartoletti.

"I think the maps are very instructive of how impartial districts could be drawn but I’m doubtful they will be utilized by LATFOR because of the political reality," said Dadey.”

The Compromise

Gov. Andrew Cuomo has promised to veto any lines that are drawn up by LATFOR, but he has also indicated that a veto would cause chaos—chaos that he would like to avoid. For months Cuomo’s office has been negotiating for a compromise that would avoid a veto. So far nothing has come of it. Cuomo’s office did not return calls for comment.

If such a deal came together it is unlikely to make use of Common Cause’s maps, as they are based on the kind of change that would happen if politics were not involved, whereas current negotiations are based on what will get senate Republicans to the table to agree to some sort of compromise.

Dadey said that he has spoken with the three parties involved in the negotiations. "Even though we may add a level of openness to the 2012 process it will be a political decision and Common Cause’s maps are apolitical," said Dadey.

The idea is to achieve a deal that would see less drastic change this year but perhaps something more substantive for the next round of redistricting in ten years. There is a sense among some at the negotiating table that Common Cause’s lines could frighten Senate Republicans away.

"To achieve reform we will need the unusual convergence of interests that include the Senate Republicans. Any reform any reform must treat all parties fairly now and in the future," said Dadey.

Others see things differently. They think the lines might make Senate Republicans more apt to make a deal that would avoid a veto, which would mean putting their future in the hands of a judge—especially when a judge could use Common Cause’s lines as an example of what districts might look like with without legislators drawing them.

But other advocates point to New York’s demographics and the fact that a majority of New Yorkers are registered Democrats.

Krueger thinks that Common Cause’s lines will serve as a guide post for LATFOR, Cuomo, or the courts if it does come down to a veto. Now that the public has been informed about the process, Krueger thinks it will be hard for LATFOR to ignore the fact that people are watching and won’t accept the excuses LATFOR used to make, excuses like, "There was no other way we could have drawn them."

Common Cause isn’t the only group allowing people to try their hand at redistricting. Fordham University is holding a competition for teams to redraw New York’s district lines. One of the participants is a ten-year-old child from Michigan.

Just How Bad is it?

A recent report by Citizens Union showed just how integral the redistricting process has been to keeping incumbents in their seats and maintaining the balance of power in Albany. The report showed that 96 percent of incumbents have been reelected since 2002. In 2006 100 percent of incumbents were reelected. The report shows that the current redistricting process makes elections far less competitive and as a result reduces voter turnout. Furthermore the report shows that minorities are underrepresented. "There are 15 different Assembly districts in New York City where the Asian-American population exceeds 20 percent, but there is only one [Asian] representative in the Assembly," Citizen Union’s Alex Camarda.

10 Years Later: Enumerating the Loss at Ground Zero

The direct losses to New York and the United States from the World Trade Center attack are incalculable when one considers the personal and emotional loss to family and friends of the victims, as well as to all other New Yorkers, who have contended with the specter of 9/11 during the past decade. Yet, the magnitude of the losses and especially the recovery are being calculated daily. Indeed, Mayor Michael Bloomberg recently claimed: "As we look back on the past decade, and as the picture of what has happened here comes into sharper focus, I believe the re-birth and revitalization of Lower Manhattan will be remembered as one of the greatest comeback stories in American history."

Other aspects of the impact of the tragedy also can be measured. Here we use demography to look at the victims, the neighborhood and the financial businesses -- the so-called FIRE or Finance, Insurance and Real Estate, sector -- to gauge the magnitude of the loss and extent of the recovery from 9/11 for Manhattan and the city. As we will see though Lower Manhattan has come back in certain respects, Manhattan no longer accounts for over half of all employment in the FIRE sector. Perhaps, this is not surprising given the magnitude of the attack.

Individuals and Businesses Lost

Information provided by the medical examiner and the Federal Emergency Management Agency and unearthed by the New York Times helped fill in the picture of this unprecedented catastrophe. Census information on businesses and those working in lower Manhattan before the attack throw into high relief the stark dimensions of the direct toll.

All of New York City and the United States lived through the attack, but those who died came from very narrow slivers of space, both actual and socio-economic. Indeed, more than two thirds of the 2,753 victims, or at least 1,946, died on the upper floors near or above where the planes crashed: the top 19 floors of the North Tower and the top 33 floors of the South Tower. When one adds the firefighters (343), police and other rescue workers (about 90) and the victims from the two planes (157), one has accounted for almost 90 percent of all victims.

The bond trading firm Cantor Fitzgerald lost 658 employees; Marsh and McLennan, an insurance firm, 295; Aon, another insurance firm, 176; Fiduciary Trust International, a financial firm, 87; the Port Authority, 75; Windows on the World Restaurant, 73; Carr Futures, a brokerage firm that is now part of Newedge, 69; Keefe, Bruyette and Woods, a security brokerage firm, 67; and equity analysts Sandler O’Neil and Partners, 67. All these companies had offices on high floors in the towers. Risk magazine, the trade bible of the derivatives industry, which defined much of finance in the last two decades, was having a conference at the top floor restaurant Windows on the World. Everyone in attendance, including many high executives, perished.

Given the firms for whom many of those in the World Trade Center worked, as well as the large number of firefighters and other rescue workers, the other demographic facts should not be that surprising. The victims were overwhelmingly male (about 75 percent), young (many under 40, most under 50) and white (about 75 percent). Only about 8 percent were black, 9 percent Hispanic and about six percent Asian. About 75 percent were born in the United States, and the others originated from many different countries. Together New York and New Jersey residents accounted for about 87 percent of the victims. Many of the airplane passengers came from Boston and California.

As for the neighborhoods where the victims lived, we now know that the Upper East Side had the most losses (44), while Hoboken, N.J., had the highest proportion of loss of any single area, losing 39 residents, or about one per thousand. Given the high paying jobs at many of the companies in the World Trade Center, it is not surprising that many of the victims lived in very affluent parts of the metropolitan area, including the Upper East Side and Basking Ridge, N.J.

10048 and the Financial District

The World Trade Center had its own ZIP code, bounded by West, Vesey, Church and Liberty streets. According to the census, in 2000 only 55 people resided in that zone, but in terms of business activity, the area was something to behold. Within its boundaries, some 1,294 establishments employed about 31,119 people, and 928 of these firms were in finance or real estate, including insurance.

Altogether, the 1,294 companies paid about $3.9 billion (all figures are in 2009 dollars) in wages and salaries, averaging about $126,000 per employee, far higher than the average for the New York metro salary of about $69,300 per employee. Few other ZIP codes and none outside of the Financial District rivaled the World Trade Center in generating employment income per employee. Most of the stores, restaurants and other retail establishments paid high rent to be in the trade center. Sandwich shops and other establishments, where less well-off employees worked, were mostly "just" across the street in another ZIP code.

Lower Manhattan accounted for about 3 percent of the employment and over 5 percent of the earnings in the large New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania Metropolitan area, which extends to Montauk at the tip of Long Island in one direction and to Hope County, Pa., in the other. The finance sector accounted for about 9.2 percent of the employment in the entire region, but 19.2 percent of the wages paid in the New York metropolitan area in 2000.

The 2,000 or so victims who worked in offices will never return to their desks at the World Trade Center. The many victims who served them -- from the staff at Windows on the World, to the firefighters and other emergency personnel who tried to save them --will not return either. Beyond them, another 30,000 workers, who used to work at the trade center, also do not go there anymore.

The loss of ZIP code 10048 represented a blow to the heart of the financial district. Indeed, those working there, though just a small slice of the city's population, nonetheless represented many aspects of New York City society: the wealthy older executives at the Risk conference or running some of the firms, the young traders on the make (some of whom no doubt spent their very high incomes), the immigrants working in the service fields, the computer techs, the lawyers and others all supporting the financial community defined ZIP code 10048.

The Neighborhood Today

Ten years on, data suggest that the recovery from the 9/11 is not yet complete, neither for Manhattan's financial sector nor for the area in lower Manhattan that included the World Trade Center. Many more people live in Lower Manhattan today than were counted in the 2000 census, as the singular focus on finance and the rest of FIRE sector could have dimmed.

Considering employment in downtown Manhattan south of the Holland Tunnel, in 2000 there were about 248,000 employees with average salaries of about $120,000 per year. By 2005 that figure had risen to 271,000 averaging about $115,000. By 2009 in the midst of the financial crisis, the number had declined to 268,000 and the average income had dropped to about $106,000. Though employment is up somewhat, the average wages, even before the boom and bust, has lagged those in 2000, indicating, perhaps, more employment in other less lucrative sectors and less employment in the extremely lucrative FIRE sector.

When one looks at the entire financial sector including real estate and insurance, it employed just over 400,000 people in Manhattan in 2000 with average salaries of $202,000 per year. By 2005, the number had declined to 374,000 employees who averaged $208,000, and by 2009 some 362,000 employees averaged $195,500.

Though Lower Manhattan seems to have recovered in terms of employment if not in terms of income, the financial sector in Manhattan seems to have taken a blow from which it has yet to recover. When the financial sector in Manhattan is compared to financial sector in the entire metropolitan area it is plain that some of its jobs have moved away from Manhattan. The sector in this larger region showed some decline to 2005 and then a small increase to 2009. In 2000, Manhattan accounted for 50.7 percent of the employment in finance in the wider metropolitan area. By 2005 that percentage had declined to 46.6 percent, and by 2009 it dropped further to 44.0 percent.

So 10 years after 9/11, exactly what will happen to the area that was designated 10048 has yet to be fully determined, as conflicts continue over what will be built in the shadow of the towers and who will occupy the new offices. Beyond 10048, however, the financial sector seems to have not recovered completely, though employment, if not average income, has continued to increase in lower Manhattan. It seems Manhattan has permanently lost a substantial share of the financial sector.

It is true several banks and other businesses are planning sites inlower Manhattan and in the area around the trade center, and many have moved back to the areas. Despite all of that, the FIRE sector in Manhattan still is diminished and seems to be declining relative to the rest of the metropolitan area. So beyond the memories of the victims and the grief of their families, Manhattan and New York City are likely never to fully recover the losses to the financial sector brought on by 9/11.

Source Note: All the data regarding the number of employees and wages paid are from the County Business Pattern data,which includes some data on Zip Code Business Patterns)

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.