The Perks of Leadership: Who Got What in 2009

The chart accompanying this story did not include Councilmember Melissa Mark Viverito when first published. It was updated on July 14.

The city's "cultural czar" can now take his throne as the king of capital funding at the City Council.

More than $23 million of the council's capital items were solely sponsored by Councilmember Domenic Recchia, who chairs the Cultural Affairs Committee. Approximately $17.6 million of Recchia's funding goes to citywide or other cultural projects outside his Brooklyn district.

Unlike the council's discretionary expense funding for programs, which provides a minimum of $340,419 to each councilmember annually, the council's capital funding is doled out entirely at the discretion of the speaker's office. At nearly double the size of the council's discretionary expense funding, capital funding goes only to projects like renovations, building acquisition or new equipment. It is also a far more convoluted and complicated funding process with projects that span years and, sometimes, never even get started.

For a complete listing of who got what, click here

It also receives far less attention then the council's scandal-ridden discretionary expense funding, which has been the subject of several reform measures.

An analysis by Gotham Gazette of the City Council's capital and expense discretionary funding found the council's $505 million worth of capital funding for fiscal year 2009 is doled out with less equality -- capital king, Recchia, got more than 10 times as much funding as Councilmember Tony Avella, who placed at the bottom of our list.

Similar to its expense funding, members who chair influential or budget-oriented committees or have leadership positions are more likely to garner the bulk of city funding. While the distribution of funding can be based on need, some say it's really politics at play.

Distributing Dollars

As part of a transparency initiative from Council Speaker Christine Quinn, the City Council capital budget for the first time lists each project with the council members who sponsored it.

The capital budget contains more than 1,000 projects, most involving school construction or equipment acquisition, like technology upgrades or funding for a new auditorium or dance studio. A large portion of the funding goes to parks and public housing, such as security upgrades, as well as libraries. This year, about $140 million was allocated for projects in private buildings -- mostly to nonprofits looking to renovate or acquire new space (for more on that, click here).

The council's discretionary expense funding, which went through a far more stringent vetting process this year than ever before, goes almost solely to community groups and nonprofits for programs, not property or equipment. Under the council's latest reforms, groups most undergo more intense scrutiny from its finance department, the mayor's Office of Contract Services and register with the state attorney general's office.

The status of these reviews are available in a council budget document -- known as Schedule C. Every councilmember receives at least $151,714 in funding for programs under the Department of Youth and Community Development, $108,705 for programs within the Department for the Aging and another $80,000 to allocate as he or she sees fit.

For capital funding, council members typically create lists of potential projects in their districts, prioritize them and deliver their selections to the speaker's office for consideration.

A project's inclusion in the council budget does not guarantee it will be funded. Capital projects must undergo an intensive application process with the agency overseeing the construction or land acquisition. For example, a nonprofit looking to acquire space in Williamsburg for industrial use would need to get the OK from the council, and then work closely with the city's Economic Development Corporation, providing a step-by-step breakdown of the progress of the project. A nonprofit that receives capital funding does not get reimbursed from the city until the project is complete.

While the processes for getting capital and expense funding differ, some argue that council members use both types of funding to gain political clout in their districts and beyond.

Inside City Hall, some members and council insiders say funding is given out depending on a member's relationship with the speaker and as a political tactic.

Our Breakdown

As it did last year, Gotham Gazette has analyzed the council's expense funding and found that, similar to capital funding, members of the council's leadership are more likely to get cash than other members. We are now focused on capital funding, because this is the first time the council lists which member is responsible for what projects.

Our figures contain only individually sponsored items, so projects or programs that were funded by a borough delegation or more than one member were not included in our tallies. Therefore the analysis cannot be taken as the entire picture of capital or expense discretionary funding. Check out our full list here.

|

* Funding labeled speaker is allocated by the speaker, with advice from the council body, and given for larger, citywide initiatives.

Who Got What

Our top ten for capital funding includes the chair of the Cultural Affairs Committee, Recchia, the chair of the Finance Committee, David Weprin, the chair of the Public Housing Committee, Rosie Mendez, and the assistant majority leader, Lewis Fidler.

Clearly leadership helps when it comes to getting funding, whether it's capital or expense.

"I think there is a recognition of seniority and a recognition of council people in the leadership," said Councilmember James Vacca, who is serving his first term and received about $7.4 million of capital funding. "I don't consider that unfair. I think most legislative bodies do it based on leadership."

Others say the numbers can be deceiving. For instance, Recchia may have garnered the most amount of funding at $23.5 million, but nearly three-quarters of that goes beyond his Coney Island district. Recchia funds several groups based on Broadway -- a so-called condition of being the chair of the council's cultural committee.

Recchia did not return phone calls for comment on this story.

Councilmember David Weprin, who received the most expense funding last year according to our analysis, got more than $18 million worth of capital dollars. That sum, however, was bolstered considerably by a $12.5 million appropriation to the High Line -- an elevated park project in Chelsea miles from his Queens district.

This was not the case for others in our top 10.

Councilmember Larry Seabrook, whose expense and capital spending has been under scrutiny in the press, received $8.55 million in capital funding, all of which went to public housing projects or schools in his Bronx district. Seabrook did not return phone calls for comment.

On average, a councilmember received about $6.1 million in individual capital items.

And Why

Some, however, were far below that. Councilmember Charles Barron, who is often at odds with the speaker, received $2.27 million in capital dollars. Barron said his lack of funding could be attributed to his less than favorable relationship with the speaker's office.

"I'm not their favorite son," said Barron. "I speak out and speak my mind. When you do that you're not going to be up on the speaker's list."

Barron said he plans on introducing legislation this year that would mandate all members receive the same amount of discretionary dollars, including capital and expense funding, or that it's distributed by need. "It should be based on a formula on a needs basis. It should be the East New York's, the South Bronx, Brownsville," the councilman added, referring to the city's more impoverished areas.

Some of those areas did make our top 10 list, like East Harlem, which is within Inez Dickens' district and the Rockaways, James Sanders' district.

A council spokesperson said capital funding is not allocated by an exact formula, but is given out based on a number of circumstances, including need and the number of requests.

One's relationship with the speaker may not be the only reason why some acquire less discretionary funding than others.

Councilmember Daniel Garodnick is seen as a rising star at City Hall. He lands the so-called necessary endorsements, and his name is often floated as the next City Council speaker.

But when it comes to capital funding, he lost out.

Garodnick was fourth from the bottom in our capital funding analysis. Though some might say rightly so (he represents parts of the Upper East Side, which is the district with the highest median income). Garodnick said he was satisfied with what he received in discretionary funds.

"I thought we were able to satisfy the needs of the district with the funds we requested and the funds that were allocated," said Garodnick. "We wanted to recognize we were in tough budgetary times."

While he could not recall exactly, Garodnick said he received a sum of capital dollars close to what he initially requested -- unlike Barron, who said he received about a third of what he wanted.

Others attribute their ability to bring home the bacon with how well they do or don't do their jobs. Councilmember Lewis Fidler, also the council's assistant majority leader, received the most expense discretionary funding at $985,000, and snagged a considerable amount of capital too. Fidler said he gets a serious amount of expense funding because he chairs the Youth Services Committee, which oversees a lot of the programs in the city that would be eligible for these types of grants.

"I am on leadership because I'm an engaged legislator that advocates for the needs I believe in," said Fidler. "Which is also why I am able to put together a pot of properly vetted discretionary items."

Â

Forgotten Handshakes: The '09 Budget

"We got screwed," said one advocate.

"We lost a lot of money," said another.

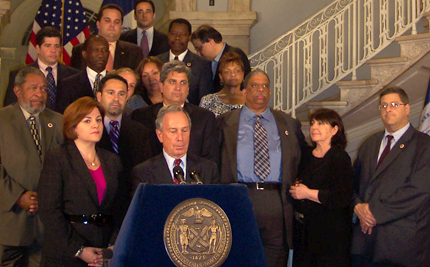

Those were not uncommon sentiments on the steps of City Hall Thursday night moments before Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Council Speaker Christine Quinn announced they had brokered a budget deal. As the sun descended four days before the beginning of the next fiscal year, some groups seemed to think their fiscal futures also were setting since the administration and City Council slashed funding for youth programs, senior centers and other services in an attempt to provide money for the city's classrooms.

"This is a question of setting priorities," said Bloomberg, who appeared particularly morose. "You can't say, 'All of the above.'"

Even though the City Council approved the budget late Sunday night, some advocates and council members continued to disagree with those priorities.

Many recognize the city faces tougher times. (Last week the Dow Jones reached historic lows for the month of June). But others argue a higher than expected surplus could have been stretched out to save community services. City officials, some advocates say, used overly pessimistic projections to cut programs prematurely. Others argue community services and programs should have been given priority over a $400 tax rebate and 7 percent property tax reduction.

Losers and Winners

An hour before midnight on Sunday -- the day before the June 30 deadline -- the City Council approved a $59.1 billion budget for fiscal year 2009 by a vote of 49 to 1 with Councilmember Charles Barron dissenting. The budget keeps spending virtually flat compared to fiscal year 2008.

It retains the $400 property tax rebate and 7 percent property tax reduction from the last year's budget. The council restored about $400 million to city agencies that the administration planned on cutting, officials said. Council members had initially hoped to restore approximately $700 million.

The city restored cuts to the Department of Education with $129 million from the City Council's discretionary funding. The budget added $18 million to the New York City Housing Authority -- about half the amount some had called for to stave off closing senior centers.

The budget also includes six-day library service, which was funded for the first time last year and put on the chopping block earlier during budget negotiations.

Overall spending increased 1.6 percent, which is below the rate of inflation. The City Council added 39 percent less to the final budget than it added in fiscal year 2008, and its own discretionary spending -- which has had its fair share of scrutiny and scandal lately -- was cut by 8 percent, said Quinn.

This year's budget announcement cited the principle of prudence. "It's a fiscally conservative, responsible budget," said Councilmember Vincent Ignizio from Staten Island.

It was also, council members said, one of the most difficult budget negotiations in recent memory, including stops and starts, impasses and frustration. “I would rather have three root canals,” said Councilmember John Liu last week regarding the negotiations.

A Questionable Surplus

Even though the budget was approved before the deadline of June 30, negotiations between the administration and the City Council sputtered partly because of disagreement on how much money there was to spend.

Historically, the Bloomberg administration tends to release conservative economic predictions.

"The mayor's job is to be more conservative," Councilmember David Weprin, chair of the council's Finance Committee, said early in the negotiation process. "The Office of Management and Budget is often very conservative with the hope that things get better. I don't think that's unusual."

In April, the council predicted the city would have $635 million more to work with than the mayor had projected. In May, the city's Independent Budget Office concluded the city would have a $4.6 billion surplus by the end of fiscal year 2008, after the mayor had warned for months of declining revenues.

On Sunday, Quinn said revenue forecasts are never a perfect science, and there was not a definitive explanation for why the council's revenue estimates were always higher than the mayor's.

Those estimates fueled the debate at City Hall. Council members pointed to them, arguing the city could afford to spend more on senior services, education and youth programs this year -- slashing services is not necessary yet, they argued.

The mayor, however, remained skeptical, which led to the cuts, some council members said.

"It went not to fat, not to muscle, but to bone," said Councilmember Lewis Fidler of the budget. Fidler stood with the mayor and speaker for Thursday evening's budget announcement, but he said he did so to show support for the speaker. He also voted for the budget on Sunday. "We were boxed in because the mayor was intransigent about spending $25 to $50 million of money that was there."

Filder, who suggested the city look at raising the hotel tax to boost revenue, continued to voice frustration over revenue projections up until the council's vote on Sunday, saying the administration intentionally kept estimates low to keep fiscal control out of the council's hands.

In a prepared statement, Councilmember Bill de Blasio voiced similar concerns over revenue projections: "I am disappointed that with a $4.5 billion surplus, the mayor forced the council to cut funding for essential services, including homeless prevention, legal and mental health services, and workforce development. In addition, the New York City Housing Authority, which is in dire financial straights, will be forced to shut senior centers and youth programs across the city. The mayor should not have put the city in this situation, and these cuts will be deeply felt for years to come."

For its part, the administration insists it is important to be prudent in these uncertain times. As a result, it put $2 billion aside for early debt payments in fiscal year 2010 and $350 million to pay expenses in fiscal year 2011. At the budget announcement, when asked why the city would not restore cuts in human services other than education, Bloomberg said the days of increased spending are over.

Quinn agreed. "We would have liked to have everything remain exactly as it was last year," she said. "That’s just not the reality of where we are financially for next year… As much good news there is in this budget, there is some bad news for some people," she added.

Saving Education and NYCHA

The good news will be heard in the city's classrooms. When the mayor and speaker said cuts would be kept out of science labs and English rooms, they got a round of applause.

For months, education advocates have blasted the administration for cutting more than $400 million from the Department of Education. They urged the city to "Keep the Promise" to children and fully fund the city's schools. Appeal letters filled mailboxes, and protests became a regularity on City Hall's steps.

Last week, one of those advocates, Geri Palast of the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, said the City Council -- not the administration -- had made the difference. "The City Council did an excellent job," said Palast. "The administration made cuts, and we were able to restore the money."

Several members had committed to voting against the budget if cuts to classrooms had not been restored, including de Blasio and the chairman of the Education Committee, Robert Jackson. Both voted for the budget on Sunday night, saying classrooms had been saved from the administration's ax.

The New York City Public Housing Authority did not do as well. Advocates and council members had been pulling for a restoration to keep the authority, mired in deficit, from closing its community centers and senior centers. While $18 million was appropriated in the budget, about half of the centers still will have to close, said the council's Minority Leader Jimmy Oddo.

The authority has 147 senior centers and 136 community centers. Advocates wanted $30 million to keep them all open.

Most council members emphasized on Sunday that it was the administration, not the City Council, that had proposed to cut spending (though they approved those cuts almost unanimously).

"The advocates and the public should recognize who cut and who restored," said Councilmember Inez Dickens of Manhattan.

Cuts Elsewhere

As opening statements were read at the council's Finance Committee meeting on Sunday, opposition to the slashed city funding was clear. A handful of advocates, who were escorted out by council security, chastised the committee for cutting funding for HIV and AIDS services.

They held up signs reading, "Say no to the City Council attack on people with AIDS." This is likely to be the first of what could be many protests over the city's spending cuts.

Other programs also will feel pain. City officials said about 2,000 summer jobs for youth will be lost, and the Department of Youth and Community Development will see an approximately 20 percent cut in its Beacon program, which puts community centers in public schools.

"This has been one of the most devastating budgets for community services that will have an impact on youth, immigrants and senior services in every community," said Susan Stamler, the policy and advocacy director of United Neighborhood Houses.

Some of these cuts led Barron, who is often at odds with the other side of City Hall and with the speaker, to vote against the budget in protest on Sunday. "Yeah, you put $129 million in for education," he said. "But look at what you did to infant mortality. Look at what you did to CUNY."

Funding for a council initiative to provide English language services and legal services to immigrants was slashed in half, said advocates, and infant mortality programs lost more than $1 million in funding. These cuts raised serious concern over how services will be affected across the city, said Jennifer March-Joly, the executive director of the Citizens Committee for Children.

March-Joly was one of a number of advocates who would have liked to see the administration and the council rescind its 7 percent property tax cut and $400 rebate to cover community services.

"The City Council and the mayor need to really focus on whether that should be done sooner rather than later," said March-Joly. "I think the magnitude of the things they can't restore will make it really difficult for the families that cant afford to go without."

Tough fiscal times, advocates said, are when these services are needed most. Given the cuts to senior and youth services, Councilmember Helen Foster questioned whether the council was too quick to pick education and classroom cuts as its priority.

"There are a lot of organizations and communities that are going to feel the pain of this budget," said Foster. "It would have been nice to spread it out more evenly," she added, referring to the council's support of different services.

An Open Window

While arguing families need the property tax cut and rebate to make it through the fiscal crises, Bloomberg did not rule out revisiting them in the future.

"When the adjustment appears not to be correct, better or worse, we have the ability to get together and change our plans," said Bloomberg. "We'll try to address it before we get into crisis mode."

There is no city regulation that prohibits the council or the mayor from raising property taxes or revising the budget later in the year -- if it comes down to that.

Some members hope the city will revisit the tax rebate as well as an increase to the hotel tax sooner rather then later. Councilmember Letitia James was the last member to offer general comments Sunday night, and she said just that.

"This surely falls on the shoulders of the richest man of the city of New York -- Mayor Michael Bloomberg," said James. Following that statement, there was a brief, practically melancholy, moment of silence in a normally buzzing chamber, roll call was called and the council approved the budget. Â

Juggling the Budget Surplus

The big fiscal news this spring is not any change in the forthcoming adopted budget for fiscal year 2009, beginning July 1. Nor is it the continuing investigations of the City Council's secret and perhaps illegal use of $4.7 million of its discretionary funds. The big news is how the mayor has already distributed the projected $6.5 billion surplus in the current fiscal year.

The use of that huge surplus shows off the genius of Mayor Michael Bloomberg's budgeting. The mayor has placated conservative fiscal monitors, he has pleased important constituencies with selective tax cuts, and he has kept the City Council out of important decisions.

One important tool for the mayor in all this has been his tight control of the budget surplus, which has precluded serious discussion about the short-term and long-term consequences of its uses. For instance, there's been little note of the fact that nearly $2 billion in reduced expenditures and services from January 2008 through June 2009 will pay for a large portion of over $2.5 billion in selective property tax rate cuts and rebates in 2008 and 2009 -- assuming the mayor does not abandon the proposed cut in the property tax rate for 2009. These cuts benefit commercial and residential property owners. Renters and the schools are among the biggest losers.

The picture of economic and fiscal gloom-and-doom laid out in the executive budget set out the rationale for the expense cuts - if not the tax cuts. But surpluses have become the norm in recent years, and with them, the mayor's discretion over the city budget has increased dramatically.

Last year's surplus, for instance, was nearly $6 billion. The two previous years' surpluses averaged over $3.6 billion. These surpluses represent significant shares of city-funded expenditures - this year more than 14 percent.

The Anatomy of Surpluses

Under state law, the city cannot end the fiscal year with a surplus. Instead, it must spend any extra monies before July 1.

This is where the mayor's discretionary power lies. As the city comptroller's May report on the executive budget points out, Bloomberg has already spread this year's $6.5 billion surplus over the next three years: $3.2 billion to pre-pay 2009 expenses, $3.0 billion to pre-pay 2010 expenses and $350 million to pre-pay 2011 expenses. The council must approve the pre-payments through a budget modification vote, but it has been reluctant to challenge these mayoral decisions.

Fiscal monitors admire Bloomberg's focus on balancing future budgets, at least in the short run. They particularly like the "conservative" revenue projections that have repeatedly under-estimated actual revenues in recent years.

On the other hand, the surpluses are mostly one-shot revenues each year - not guaranteed for the next year -- so using them dodges the problem of the city spending more than it brings in. The executive budget itself anticipates budget gaps in 2011 and 2012 that average $4.5 billion. The state comptroller in his June review of the mayor's financial plan for 2009 to 2012 estimates that the 2011 and 2012 gaps could average as much as $6.3 billion.

Creating the 2008 Surplus

How did we get to this point? The city comptroller's May report spells out where the projected $6.5 billion surplus in 2008 comes from:

- $2.6 billion from last year's (2007) surplus, set aside in what is called a Budget Stabilization Account (i.e., a reserve fund for surplus dollars);

- $2.5 billion more in revenues than the city projected last June;

- $1.4 billion in lower expenses than projected last June.

The mayor has already made an early payment of $2 billion to bring down debt service, which otherwise would have been due in 2010. So, by his figures, the current 2008 Budget Stabilization Account has $4.5 billion ($6.5 billion minus $2.0 billion). The city and state comptrollers include the $2.0 billion pre-payment and say the surplus is $6.5 billion.

Using the 2008 Surplus

The city comptroller also lists the uses of the 2008 surplus:

- $2.0 billion to pre-pay 2010 debt service;

- $3.1 billion to pre-pay 2009, 2010, and 2011 debt service;

- $500 million to pre-pay subsidies to city libraries and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority/Transit Authority;

- $400 million to pre-pay retiree health insurance;

- $546 million to the city Finance Authority for debt service.

This totals $6.5 billion.

The state comptroller's June report notes that without all the mayor's recent decisions -- rolling over the surpluses future tax increases and expense reductions -- the deficits for fiscal years 2009 to 2012 budget deficits would be, respectively, $4.9 billion, $6.6 billion, $7.6 billion, and $7.1 billion -- hardly a testament to "conservative" budgeting.

The Surplus Effects

One consequence of these pre-payments and grants -- as well as tax cuts -- is that the 2009 budget projects a $1.3 billion surplus for that year, much smaller than in recent years. 2010 has a tiny projected surplus of $350 million. The narrow focus of last-minute budget negotiations -- usually only $200 million to $300 million in changes - obscures the most important consequences of current surplus policy. The most stunning is the disconnect between the huge extra resources actually available in 2008 and the big cuts imposed during the same period.

The city comptroller's May report make this clear: Education funds, for instance (a mayoral priority), will be cut by $608 million from January 2008 to July 2009 and then by $753 million over the next two years, 2010 and 2011. That adds up to a $1.4 billion cut over three and a half years.

Compare education cuts with tax cuts. In Bloomberg's executive budget, the property tax rate cut averaging over $1 billion each year remains in place for the 2008 and 2009 fiscal years, along with the $400 rebate to house, co-op, and condo owners, at a cost of about $250 million in lost revenues each year. That adds up to over $2.5 billion in tax breaks over two years.

Last week the mayor indicated he might abandon the cut in the property tax rate in 2009, apparently because of the economic downturn and the cost of the city's recent contract settlement with police officers. However, the mayor has not committed himself to such a change, and some City Council members have indicated they would oppose any effort to eliminate the cut.

Neither the rate reduction nor the rebates have benefited renters, who represent two thirds of city households (and a substantial proportion of public school students).

Thus the $12 billion in surpluses recorded over the past two years have not so much encouraged a long-term conservative fiscal plan as created a political exercise in selective tax changes and, more recently, in service reductions.

Reforming Surplus Politics

The creation of rainy day fund would open more of these decisions to political debate. Under this plan, any surplus would go to a fund and be spent only under circumstances set by state legislation. That would limit late-year mayoral budget decisions to which the council seems to be only a rubber stamp. The council

made such a fund a priority in its response to the mayor's January preliminary budget. The city comptroller added his voice to that argument in his May report.

"Establishing a statutory rainy day fund would enable the city to manage its finances in a more transparent and straightforward fashion. The present method of applying surplus resources to future years is complicated, difficult for the public to understand and in some instances lacks flexibility that would allow resources to be applied where they are truly needed. ... The comptroller continues to urge the city to explore establishing such a fund," his report said.

Prospects for such a fund are dim in the short run. State legislation would be required, and the mayor would presumably try to block it. One way to move toward legislative action would be to make the creation of a rainy day fund a priority for any Charter Revision Commission the mayor might name in the near future. However, here again, the mayor controls the appointments and agenda of such a commission. Thus any reform may have to await debate among mayoral -- and City Council -- candidates in the 2009 election campaigns.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â