Council Cracks Down on Pedicabs Again

The City Council tapped the brakes on New York's pedicab industry Thursday by approving legislation to further regulate the sometimes rogue, tourist-friendly tricycles rampant in Midtown.

The council capped the number of pedicabs at 850 and made it easier for the city to suspend pedicabs' licenses after drivers receive multiple violations.

The move was the second attempt by the City Council in two years to curtail the growth of pedicabs, which up until 2009 were completely unregulated.

"We are at our saturation point with pedicabs," said Councilmember Dan Garodnick, the bill's sponsor, who represents Midtown East. "This is not the appropriate time to issue new licenses.

In addition to the pedicab proposals, the council also approved legislation that could ease alternate side parking regulations across the city.

A spokesperson for Mayor Michael Bloomberg said the administration supported both measures.

Pedicab Problems

Stop by Central Park and you can't miss them.

The oft-colorful wheeled wagons shuttle tourists and Midtown revelers from the park to Broadway to restaurants. While the human-powered taxis are often full, residents and the taxi industry have complained about them for years, citing safety hazards.

The council initially attempted to regulate pedicabs in 2007, but the rules were struck down in state court.

In 2009, the council successfully established a licensing system for the industry for the first time.

Under the current system, pedicab operators had a limited time frame to apply for a pedicab license at the Department of Consumer Affairs. The pedicabs must stay out of bike lanes, pass inspection, and have seatbelts, tail lights and insurance.

On Thursday, the council went a step further. Under the legislation, which was approved by a vote of 44 to 1 with Councilmember Charles Barron dissenting, the city will not issue new pedicab licenses unless the number of vehicles falls below 840.

The new proposal would rescind a pedicab's registration plate for a year if it receives three violations within one year. Those violations could include broken seatbelts or brakes.

The Department of Consumer Affairs also would have the power to revoke a pedicab driver's license if he or she operates the vehicle twice in one year without a valid driver's license or with a suspended license.

The council also approved legislation to force pedicabs to abide by the city's parking regulations. Pedicabs would no longer be able to park in no standing or no parking zones, and they would have to steer clear of fire hydrants.

The city's leading pedicab association, the New York City Pedicab Owners' Association, testified in favor of the proposals.

But not everyone in the industry has lent their support.

"I think its pretty unnecessary," said Robert Tipton, the owner of Mr. Rickshaw, a pedicab company, of the parking regulations. "There are other issues that are more pressing, one being the driver's license issue."

Currently, to obtain a pedicab license you only need a driver's license that is valid in New York State, which would include those issued in other countries. Tipton suggested the city should only allow drivers with U.S. driver's licenses.

From Pedicabs to Parking

Moving to the curbside, the council also approved legislation to allow community boards to reduce the number of days for alternate side of the street parking if the neighborhood meets certain cleanliness standards.

The street would have to obtain an average 90 percent cleanliness record for two consecutive years before the community board could move to reduce the number of alternate side days.

Under the legislation, which was passed by a vote of 44 to zero with one abstention, no street would be allowed to go below one alternate side day per side.

The city initially piloted reduced alternate side in Brooklyn starting in 2008. The council also approved legislation to require the Department of Information, Technology and Telecommunications to create an interactive map that would keep track of all street closures.

Republicans Look to Trade Payroll Tax for Bridge Tolls

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority has been conspicuously absent from the Albany debate this year. But as the session winds down slowly, the MTA and its issues are creeping back to the forefront, thanks to a group of upstate and Long Island Republican senators who want to drastically cut back the payroll tax that helps pay for mass transit and commuter rail. At the same time, they would pave the way for tolls on the East River bridges, an idea that has been touted as a solution to both the MTA's chronic fiscal woes and Manhattan's traffic congestion. This time around though, even some supporters of the tolls have their doubts.

The Tax

In 2009, with the MTA facing a huge budget gap, the state government enacted a tax in the city and counties serviced by the MTA including Putnam, Westchester, Rockland, Orange, Suffolk, Dutchess and Nassau. The tax as it stands raises $1.34 billion annually for the MTA. Although it amounts to only 0.33 cents on every $100 dollars paid by employers, many politicians from these areas have opposed it, saying the MTA provides limited service in their districts and most of the businesses in their counties don't benefit from it.

Sen. John Bonacic, whose district encompasses Delaware County, Sullivan County and parts of Ulster County and Orange County, has introduced a bill that would do away with the payroll tax in all counties except New York City. To make up the revenue he would allow -- but not require -- the New York City Council to set tolls on the East River Bridges: the Brooklyn Bridge, the Manhattan Bridge, the Williamsburg Bridge and the Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge. The charge could be between $2.50 and $5. This idea has been frequently proposed before -- most recently in 2009-- and has always failed.

Bonacic has the support of fellow upstate Republican Sens. Gregory Ball, William Larkin, Stephen Saland and Lee Zeldin. The bill does not have a sponsor in the Assembly as of this writing, although Bonacic has reached out to possible sponsors and notes that a number of Assembly Democrats y voted against the payroll tax in 2009.

Time for Tolls?

Although some transit advocates have supported tolls or charging people to drive into Manhattan in the past, they expressed reservation about Bonacic's plan.

Advocates like New York Public Interest Research Group's Gene Russianoff say there are simply too many variables that could leave the MTA with a gaping financial shortfall. If the council decided not to implement tolls or implemented very low tolls the MTA would end up losing money. "The bill does not set a toll rate," says Russianoff. "It only allows the council to implement them." He added that some studies concluded that a $3 toll, such as one previously recommended by Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, "would cost us money."

Neysa Pranger of the Regional Plan Association says that the MTA's finances are not particularly strong especially when it comes to its capital plan. "We need to be looking for new sources of funding not getting rid of them," she said.

Bonacic, however, thinks the tolls would provide more than enough money. He says that the payroll tax in the suburbs is supposed to generate $343 million a year, while the tolls could generate as much as $533 million annually. "I think the revenue stream from tolls would generate about a $200 million surplus. It's a revenue enhancer they can spend as they see fit." Bonacic did not say how much he thought motorists should be tolled.

The debate revives talk of congestion pricing, which many transportation advocates, including Russianoff, favor. Mayor Michael Bloomberg has reportedly been working on a revamped version of congestion pricing called "traffic pricing" as a way to better fund the MTA and perhaps reduce fares. Bloomberg's plan, however, supposedly would not roll back the payroll tax. Bloomberg recently talked about funding mass transit through "pilot technology and pricing based mechanisms," while introducing his environmental plan earlier this month.

The City vs. The Suburbs

For Bonacic the debate comes down to one of usage and services. He says train service in the small part of Orange County that he represents has not improved since the tax was implemented. He describes the situation as, "taxation without transportation."

At the same time, Bonacic says the payroll tax hurts not-for-profits and businesses. "This stunts job creation," he said. He said that the payroll tax raises $18 million per year in Orange County where only 2 percent of resident use MTA services. "The legislature implemented this when everything was controlled by Democrats from New York City. The passion against it has not subsided," he said.

But Russianoff disagrees. "People may say, 'Well, I don't take the train,' but the people who go to the florist may come up on one, the people pushing the shopping carts may have gotten there thanks to MetroNorth or the subway or bus."

Russianoff described the situation as a slippery slope. "If they think it isn’t worth paying for the service then what about the other MTA taxes, like the sales tax? I don’t think it would be fair for subway and bus riders. I think in the end it would cost the MTA funding."

Pro and Con

Meanwhile, city legislators say that tolls on the East River bridges would hurt their middle class constituents. Sens. Tony Avella and Toby Ann Staviskyissued a press release slamming the plan. "Tolls are a tax, and middle class families can’t afford to keep paying more while getting less in return. The legislation proposed by Long Island and upstate Senate Republicans to place tolls on the East River bridges will adversely affect commuters, small businesses and working families in outer-borough communities who have very limited access to public transportation," it said.

Bonacic is trying to sell the plan as environmentally friendly. His arguments for the tolls are similar to the ones made for congestion pricing. "Everyone who goes into New York should pay their fair share. It would reduce traffic and be better for the environment if people started using public transportation more."

But the truth is any bill that features bridge tolls faces an uphill battle in Albany, and Bonacic does not yet have bipartisan support on the bill, although the first supporter he wants to bag is a big one. "I need [Gov. Andrew] Cuomo to get behind this, because he has said he doesn't like the payroll tax. But this is just the beginning," the senator said.

During a visit to Poughkeepsie in January Cuomo called the levy on payrolls "a very onerous tax.' He went on to tell reporters, "It's not just in this area; people are complaining about it on Long Island, the entire metropolitan region. ... I understand the need to finance the system. If we can find a better way to do it, I’m open."

The Independent Democratic Conference, made up of Sens. Diane Savino, David Carlucci, David Valesky and Jeff Klein, also has made repealing the payroll tax part of its agenda. Klein, the leader of the breakaway group, listed the payroll tax as one of the biggest mistakes the Democrats made while they were in the majority. However, Savino and Valesky voted for the tax in 2009.

It's not clear if the four would support tolls. The group has said it blames gross mismanagement" for a third of MTA’s current fiscal debt." In its agenda, they say, "Our goal is to conduct a comprehensive forensic audit of the MTA to find areas of waste and corruption and determine the need and the efficacy of the current MTA tax."

Whether or not his bill gains traction, Bonacic expects the next two months will see more legislation that will propose other ways to fund the MTA and do away with the payroll tax on upstate counties. "There are enough upstate legislators who recognize this is simply unfair," he said.

Russianoff also anticipates major debate over how to fund the MTA before the end of the session. As for Bonacic's bill, he said, "We don't support it, but I think it raises an interesting question about what would it take to get the legislature to seriously consider bridge tolls, whether they were connected to payroll tax or not."

City Again Tries to Get New Yorkers to Board Ferries

Instead of packing onto crowded, often delayed and inconvenient subways, commuters along the Brooklyn/Queens waterfront will have an alternative way to travel when a new ferry service begins making stops along the East River later this year.

The service is the latest in a long line of attempts to boost commuting by water in New York in an effort to revitalize the waterfront and ease congestion. It comes in the wake of a few successes and many failures. The ferries, which will serve Greenpoint, Williamsburg, DUMBO, downtown Brooklyn and East 34th Street, will be operated by BillyBey Ferry Co., which contracts with NY Waterway and whose boats bear the NY Waterway logo.

"You can see from Edgewater to Weehawken all the way down to Hoboken and Jersey City that development has occurred on the Jersey side where the ferries were helpful to developing, and that's the development the city is trying to encourage on the Queens/Brooklyn waterfront," said Paul Goodman, co-owner and CEO of BillyBey Ferry said.

According to the city Economic Development Corp., the East River ferry system will cost passengers $3 to $5.50, depending on distance. Currently, the city is constructing piers for the new service, and hopes to have them operating by the time boats are ready to take passengers -- probably by June, although no date has been announced. According to development corporation spokesperson Julie Wood, if the new service becomes a success, the city will look to expand ferry service in other places.

Better by Boat?

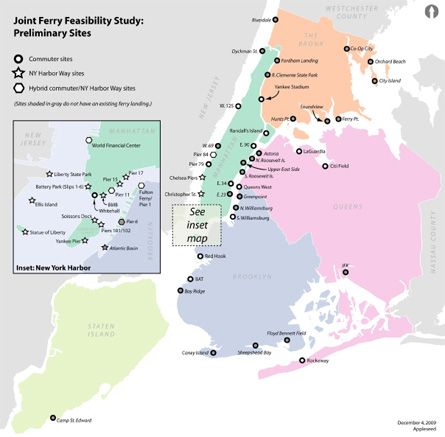

The development corporation has been analyzing over 40 sites around the city to see if ferry service is feasible. According to its Comprehensive Citywide Ferry Study, new ferry service could serve a number of locations throughout the city including LaGuardia and Kennedy airports, Coney Island, Bay Ridge, Soundview, Hunts Point and City Island.

"Using the waterway to connect New Yorkers to business districts as well as recreation destinations will encourage economic activity and growth on both sides of the East River," said development corporation president Seth Pinsky in a press release.

The project is part of Mayor Michael Bloomberg's Waterfront Vision and Enhancement Strategy (WAVES) initiative for the revitalization of 578 miles of city waterfront. The initiative calls for the redevelopment of the city waterfronts. One of WAVES' goals is to promote increased use of New York waters for transportation. Woods said the new ferry service will be part of that. "It's activating the blue network, it's consistent with all of the goals of waves to increase waterborne transportation," she said.

WAVES also aims to restore the natural habitats of wetlands in the Bronx, Brooklyn and Manhattan, and encourage and improve maritime commerce. The WAVES initiative, according to the city, reinforces some of the goals of the PlaNYC 2030 initiative, which has sought to encourage alternate modes of transportation including ferries.

"Many of New York City's fastest growing neighborhoods, like Williamsburg and Long Island City, have tremendous waterfront access, and we want to capitalize on that by providing a new, sustainable transportation option for residents," said Deputy Mayor for Economic Development Robert Steel in a press release.

The service will run every 20 minutes during the day and evening, serving seven stops year round and two additional stops -- at Governors Island and Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn -- during the summer. This, Steele said, will "create a transportation alternative while spurring private investment along the waterfront."

Beached!

The new ferry service comes after years of unsuccessful effort to promote ferries. In the mid-1990s, then Gov. George Pataki and then Mayor Rudy Giuliani asked NY Waterway to provide service between Hunters Point and East 34th Street. The ferries ran between every 15 to 20 minutes, but only carried 135 people per day at its peak. The service was not subsidized by the city and ended in 2001.

In 2002, NY Waterway once again tried to bring ferries to the East Side of Manhattan. The ferry served the 90th Street pier on the Upper East Side, Long Island City, 34th Street and Pier 11 in Lower Manhattan. Costing only $5 per trip, the ferries operated every 30 minutes during rush hour and had no off-hour service. The second attempt faltered due to low ridership, having only carried 150 people per day. Upper East Side opposition to shuttle bus service NY Waterway provides to its terminals further complicated matters, and low ridership from Long Island City resulted in the service ending once more in 2004.

The administration also has attempted to bring ferry service to other parts of the city. In May 2008, NY Water Taxi offered service from Breezy Point in The Rockaways, to Bay Ridge, Brooklyn and Lower Manhattan. Despite having community support, the ferry only served 160 people per day and cost the city $1.5 million in subsidies. The service endedlast year 2010.

If at First You Don't Succeed...

Goodman and others hope this time will be different. Previous attempts, according to Goodman "were not the same effort as the one were doing. ... This time around, there are half a dozen departure points. ... It's a very robust schedule -- a degree of frequency at different locations on a scale never been attempted before."

In addition, the ferries will link up to a free bus service in Midtown as well as to the M34 bus. The ferries also will accommodate bicycles.

"This robust, regular service will be well-integrated with existing transportation options, providing a new sustainable and enjoyable way for commuters and tourists alike to get around the city," said Pinsky.

Despite all this Goodman warns that ridership levels could be low in the beginning, although he expects that to change. "It could take time for the ridership to develop as communities along the waterfront develop," he said, adding, "We think in the long term that it' s going to be viable. ... Access to ferries should enhance development on the waterfront, which should increase ridership."

According to NY Waterway spokesman Pat Smith, the city has dedicated $3.1 million in funding per year, over a three-year period.

"In order to make it affordable to the potential riders, the city is subsidizing. It is priced at a point that makes it attractive with other subsidized transportation," said Goodman.

NY Waterway and BillyBey already operate ferries across the Hudson River between Manhattan and New Jersey. According to New York Waterways, its ferry system helps to keep 7,000 cars off the road, and carries 30,000 passenger trips per day.