Concerns Raised over City Role in Deporting Immigrants

Growing up in Mexico City, Ricardo Muniz dreamed about being able to just be himself someday. He always knew he was gay and was constantly subject to anti-gay slurs or even death threats.

"It's difficult to come out in Mexico," said Muniz. "I don't remember a happy childhood."

At 15, shortly after he came out, his mother was so concerned about his well being that she sent him to New York to live with his aunt. "I heard there is justice and people can be who they are regardless of their sexual orientation," said Muniz, now 25. "I wanted to start a new life in America, to be free."

But he didn't realize that the real America differed from the one he imagined. After spending 20 months in detention, Muniz now faces deportation back to Mexico -- even though he has not been convicted of any crime.

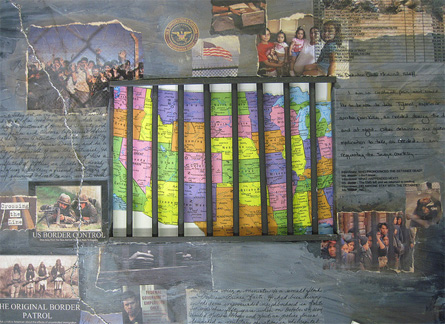

Muniz is one of many immigrants who face deportation after being caught up in the criminal justice system -- regardless of the charges against them and regardless of whether they are guilty. Under a federal program called the Criminal Alien Program, New York City law enforcement officials give the names of all people arrested to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, known as ICE. If ICE identifies someone as an immigrant, then the agency asks to transfer the person to federal facilities where the immigrant remains pending deportation hearings.

The city Department of Correction has given names to the federal government and allowed for the transfer of immigrants -- despite Mayor Michael Bloomberg's outspoken support for immigration and his issuance of Executive Order 41, which prohibits city workers from inquiring about immigration status when the people seek services from a city agency or witnesses a crime.

A Fight's Consequences

The trouble for Muniz began in July 2009 when he and his friends were attacked with bats and belts after a quarrel with a patron at a bar in Brooklyn, according to the report Muniz filed with the police. He suffered serious injury in his face and body.

"Ricardo was a victim of a hate crime," said Karina Claudio-Betancourt, a coordinator and interpreter at Make the Road New York, an advocacy group serving low-income people.

During the fight, the patron, a 65-year-old man, fell and injured his head, resulting in a lengthy hospital stay. A few weeks later, the police arrested Muniz and his friends, charging them with assault.

That began a nightmare that still haunts Muniz. He was held at Rikers Island pending trial because the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement placed a detainer on him. A detainer is the document the federal government issues to a local jail or correctional facility when ICE wants custody of an immigrant, legal or illegal, in that facility for purposes of instituting removal proceedings.

"I had double difficulties because I am gay and Latino," said Muniz of his time in jail. "I was attacked numerous times and verbally abused. People stole my food and hit me because of my sexual orientation."

"It scarred me psychologically," added Muniz, who broke down several times during the interview. "This is the experience I would not wish on anyone."

In late March, he was exonerated and released, ending 20 months in jail for a crime that he never committed. But Muniz now faces deportation because he is undocumented.

How It Works

Generally, when a deportable immigrant is released from jail because he or she finished his sentenced or was found innocent, the jail receives a request from ICE to detain the person for 48 hours. This gives ICE enough time to transfer this person to a federal facilities, many far from New York City. Once the arrestees are transferred to remote facilities, the chances of getting legal help become slim. Although the Criminal Alien Program may focus on undocumented immigrants, a report by the Immigration Policy Council found, it "identifies legal immigrants as well as unauthorized immigrants who are deportable based on the current crime or a prior crime."

Many of the detention facilities are in poor conditions and provide inadequate access to medical care or communications. According to the ICE's own figures, 120 immigrants died in detention between 2003 and March 2011.

The city does not have to comply with the federal government's request to hold the immigrant, said Bridget Kessler, a clinical teaching fellow for the Cardozo Law School Immigration Justice Clinic. She said a detainer from ICE is non-binding. In fact, many cities around the country have chosen not to participate in ICE's efforts, such as Berkeley, San Francisco, and Chicago.

Calls for Change

In an op-ed column in the New York Times by Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer and Andrew Friedman, a co-executive director of Make the Road New York, called on Bloomberg to follow these cities and change New York's policy.

Most of the immigrants transferred to federal custody and then deported "have their due process rights violated," they wrote. "The process is too rushed to ensure proper identification of status and identity, let alone confirmation of criminal background."

Stringer and Freidman charge that New York's involvement in the policy costs the city millions of dollars and deters immigrants from reporting crimes. But they say, "Perhaps what is most disturbing is that sometimes legal immigrants who have been convicted of no crime are caught up in this system."

The column also mentions the pressure on local governments to adopt Secure Communities, a program designed to identify immigrants in U.S. jails who are deportable under immigration law. Under Secure Communities, participating jails submit fingerprints of those arrested not only to criminal databases, but to immigration databases as well. The program is scheduled to be in every jail in the country by 2013.

Meanwhile, to counter the growing trend of adopting programs like Criminal Alien Program and Secure Communities, the Association for the Bar of the City of New York in February submitted a proposal to limit the collaboration between the city Department of Correction and ICE. The association instead calls for the city to allow immigrant New Yorkers to face deportation charges here, rather than in remote places far away from supportive family members and available pro bono or otherwise affordable legal counsel.

The mayor’s office, though, has defended its decision to cooperate with ICE, saying it is a public safety issue.

"The mayor’s Executive Order 41 allows immigrants to gain access to city services and report crimes with no fear of being questioned about immigration status,” John Feinblatt the mayor’s chief policy advisor and criminal justice coordinator wrote in a letter to the Times. "But when it comes to immigrants arrested for criminal activities, the executive order ensures cooperation with federal authorities."

Raising the specter of terrorism, Feinblatt continued, " As our country has learned tragically, when government agencies fail to cooperate and share information, not only is public safety compromised, so is national security."

To Muniz, such statements are ironic.

"I am a hard worker. People like me should be protected," he said. "In this country, you are supposed to be innocent before proven guilty. But it is the other way around."

Despite his misfortune, he has been luckier than most detainees. One of his friends also involved in the fight was deported before any trial. According to a report titled Jailed Without Justice released by Amnesty USA, more than 80 percent of immigrant detainees do not have legal representation.

"There are many people out there who cannot speak out," said Muniz. "Many of them are innocent. They are hardworking people just like everybody else."

Muniz thanked his mother for seeking help from non-profit organizations when his was in jail. The Cardozo Law School Immigration Justice Clinic has submitted a request asking ICE to release him because of the harsh circumstanced that he has been subject to and to stop the deportation proceeding. ICE granted the first request but denied the second.

Muniz is due back in court for his status hearing soon. Currently he is in a program called Alternative to Detention and is required to report to ICE on a regular basis.

Larry Tung is a Brooklyn-based journalist and media artist.

Court Allows Man Who Falsely Confessed to Murder to Seek Money from the State

Recently Gotham Gazette reported on the confession of Douglas Warney, who was convicted for a 1996 murder in Rochester but was later exonerated when DNA determined he was actually innocent.

Nevertheless, two New York courts found that he should not receive a state settlement compensating him for his wrongful conviction and the subsequent nine years he spent in prison. The court said his false confession constituted misconduct and so barred him from receiving compensation.

In late March, though, the state's highest court ruled in Warney's favor, reversing the lower courts' dismissal of his claim.

Warney's lawsuit seeking compensation had been brought in the Court of Claims, which hears cases against the state. In its ruling, the court is to rely on the Court of Claims Act and the Unjust Conviction and Imprisonment Act, which requires that a claimant seeking compensation had been convicted of a crime, sentenced to imprisonment and served at least part of the sentence. In addition, in order to receive a settlement, the claimant must have been pardoned on the ground of innocence or had a conviction that was reversed, vacated or dismissed.

The Court of Claims, however, rejected Warney's suit because language in the statute bars compensation for wrongful convictions that were caused by the defendant's own "misconduct." In other words, although DNA unequivocally proved that Warney is innocent, the confession he gave the police, which was used to convict him, constituted "misconduct" in the view of the Court of Claims judge, Renee Forgensi Minarik.

Allegations of Misconduct

The specific issue confronting the Court of Appeals was whether Minarik had improperly dismissed Warney's case without allowing the litigation to proceed further. The judge had decided that Warney's papers at the earliest stage of litigation should disclose in detail how his confession came about. The Court of Appeals opinion written by Judge Carmen Ciparick/a> agreed with Warney's counsel, Peter Neufeld, that Warney did not have to submit his evidentiary proof that early in the litigation proceedings.

Judge Robert Smith, who appeared particularly concerned when the case was argued in Albany, had posed many questions to the state's attorney, Alison Nathan, who is expected to become a federal judge. Smith asked how Warney could have confessed to specific facts of the crime that he couldn't have known both because of his limited mental abilities and because there is no question that he is innocent. Smith questioned whether the police interrogators gave Warney information, known only to them and the real perpetrator, that Warney then parroted back when asked about the murder.

At oral arguments and in his concurring opinion, Smith referred to the meaning of "coerced confession" and defined it as the sort of "calculated manipulation that appears present here." In general, though, Smith concurred with the majority opinion, which relied largely on procedural technicalities surrounding the dismissal. It did not give Warney's lawyers an opportunity to prove that it was not his acts that constituted misconduct. Smith feared that would lead to more general arguments against dismissal.

Criminal Knowledge

Warney, who had a history of making false police reports, has claimed that he had been denied access to a lawyer after police detained him for questioning in the murder. Warney eventually admitted to the murder in an unusually detailed confession -- one containing details that only the true perpetrator and the police could have known. But after he was convicted and sentenced to 25 years to life, Warney, who was then represented by the Innocence Project, claimed innocence. It was nine years later that DNA testing excluded him as a match. His conviction was reversed based on newly discovered evidence.

In ruling on Warney's request for compensation, lower courts said Warney had not offered convincing evidence that the police must have fed him detail of the crime. Ciparick's opinion reversed the lower courts , which had said that Warney would have had to present convincing evidence in the initial litigation on a possible settlement that the police fed him the details.

The appeals court determined that Warney did not have to prove his case in the lower courts but simply provide enough evidence to keep the case in court for trial. In other words, the Court of Appeals found it was premature for the Court of Claims judge to decide that she was not convinced by the facts Warney presented.

In his submission to the Court of Claims, Warney maintained that his conviction "was the direct result of the intentional and malicious actions of members of the [police] who fabricated and coerced a false confession from ... a man whom they knew had a history of serious mental health problems."

Referring in his opinion to some of the details in the confession, Smith asks, as the prosecutor had asked the trial jury, how a man whose innocence has been established could have known some of these facts he presented during police questioning.

"It is hard," Smith writes, "to imagine an answer other than that he learned them from the police. ... The police took advantage of Warney's mental frailties to manipulate him into giving a confession that contained seemingly powerful evidence corroborating its truthfulness -- when, in fact, the police knew, the corroboration was worthless. ... This sort of police conduct, if proved at trial would be sufficient to show that Warney 'did not by has own conduct cause or bring about his conviction.'''

Answering a question asked at oral argument, Smith said a false confession that was not coerced could be a barrier to compensation from the state. But, he wrote, "A confession cannot fairly be called 'uncoerced' that results from the sort of calculated manipulation that appears to be present here -- even if the police did not actually beat or torture the confessor, or threaten to do so. "

As clear as he appears to be about Warney, Smith is at least equally concerned with discouraging "frivolous claims." "This case is easy, because this claimant appears ... to have an exceptionally strong case," Smith wrote. "Our decision today should not be read as implying that any claimant can, by skillful pleading, get a significantly weaker case past a motion to dismiss."

According to Neufeld approximately 25 percent of those individuals who have been exonerated had confessed to crimes they did not commit. This week, Jeffrey Deskovic, who spent 15 years in prison after being convicted of raping, beating and strangling a high school classmate, but was later exonerated by DNA testing, settled his federal civil rights case against Westchester County for $6.5 million.

While it is not every day that cases such as Warney's and Deskovic's are brought, Neufeld hopes that the opinion in Warney's suit will have an effect on other local cases and in other states. That is, while false confessions are not uncommon, they should not generally prevent an exonerated individual from claiming compensation. Certainly as Smith wrote, the wrongfully convicted should have their day in court and an opportunity to establish their claim.

Other claims, though, will wait for another day. The next question would involve whether there will be a trial in Warney v State of New York. According to Peter Neufeld, there have been no discussions with the state about how the case will proceed now that the Court of Appeals has reversed the dismissal. It is likely the two sides will reach a monetary settlement.

Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court Justice

Prosecutors Grapple with Marijuana Arrests

Several years ago in a private conversation, a Fire Department paramedic explained the tension between the New York Police Department and EMS when their units respond to situations involving illicit drugs. Police officers, he said, view drug use as a criminal matter. Paramedics and other medical workers see it as a public health concern.

For years, criminal justice reform advocates have said that non-violent drug offenders should be referred to treatment rather than sent to jail. In 2009, the state scrapped many of its Rockefeller drug laws, a landmark victory for these advocates in the state. But whether the state is moving to view the non-violent drug user as a victim of an epidemic rather than someone who belongs in a holding cell remains to be seen.

More specifically, the state has not addressed how to deal with a person found with marijuana who doesn't need either incarceration or treatment.

Limited Options

So far, implementing Rockefeller drug law reform has been messy and costly, said Glenn Martin, the vice president of development and public affairs at the Fortune Society.

Although prosecutors push more first-time drug offenders toward drug-treatment, most of them wind up in 18-month, in-patient programs. The justice system by and large ignores other types of clinical care, and the state offers few alternatives to incarceration. In particular, Martin noted, treatment has largely been an option for first-time offenders, rather than those who relapse.

"It sounds good to a prosecutor, but who says that this cookie-cutter approach makes sense? It doesn't,” he said in a phone interview. While many prosecutors support the idea of treatment over jail, Martin says they are not usually experts on drug and alcohol rehabilitation.

"New York City has the most robust alternative to incarceration communities," Martin said. But, he added, "None of those resources are utilized."

On paper, the state's drug enforcement methods appear kinder and gentler. But the reforms, Martin argues, have not met the goal of reducing the money spent on tackling drug use and actually rehabilitating people.

"Not a single person has completed treatment," he said. "You can't point to success stories yet?"

Getting Arrested

The treatment debate does not address the issue of why so many people are arrested in the first place. Speaking at a recent panel discussion at the New School, Staten Island District Attorney Dan Donovan said his team of prosecutors “have great discretion” when it comes to diverting alleged marijuana offenders into treatment programs. But he also said many people caught on misdemeanor drug offenses are brought in under questionable circumstances -- like through a stop-and-frisk, which forces individuals to empty their pockets. (Note: it is not a criminal offense to be in possession of a small amount of marijuana, but it is a misdemeanor to have it out in public).

Donovan said that in those instances, prosecutors can move to not press the case. "We got real smart with that," he said. When asked how many cases it has put aside due to improper searches, Donovan said: "I don't think we’ve ever broken that down."

Simply being caught up in a criminal proceeding, however briefly, can create problems, even if the case is dropped or the young drug user is sent to treatment, said Noah Kass, the clinical director at Realization Center, an outpatient treatment program in Brooklyn and Manhattan.

"The trauma of being arrested for a crime you didn't commit is significant for an adolescent. The trauma of being arrested for a crime that's unwarranted could be astronomical," he said. "It sets them on a road. It almost becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy."

User vs. Abuser

Kass said he often finds himself in situations placing young people -- particularly blacks and Latinos -- caught with marijuana into treatment that they don't really need.

"So I will stick a kid who is 15 or 16 who grew up in the South Bronx and was caught with a very little amount of marijuana, and I will stick him in a group with a kid who goes to a private school on the Upper East Side who is suffering from so many more drug issues that comparing them could be futile," he said.

Kass recalled that one of his workers in such a situation worried that the rich kid would learn the "drug game" from the Bronx youth. Kass said, "I was like, 'It is so the other way around.'"

By placing youth in treatment when they do not have real drug problems, the criminal justice system is telling them that they do. This can greatly affects a person's psyche, and is an all too common reality for black and Latino youths in the city, Kass said.

"They say, 'Yes, I’m going to self help meetings. Yes, I'm working on building a solid sober support network,'" he said. "We become sort of complicit in this lie."

If Kass is correct, then the mental health impact on New Yorkers caught with marijuana, arguably the least dangerous of illegal drugs, could be enormous. Last year , the city arrested 50,383 people for possessing small amounts of marijuana. according to a recent report by the Drug Policy Alliance. Gabriel Sayegh, director of the New York office of the Drug Policy Alliance, said the number of marijuana arrests under the Bloomberg administration dwarfs the number of such arrests under Mayors Ed Koch, Davd Dinkins and Rudy Giuliani combined.

Nonetheless, advocates still believe some progress has been made toward treating drugs as a health concern more than a crime problem.

"I think the movement is very marginal, but I think about how long it took to get here," Martin said. "I find myself in rooms with prosecutors now who are comfortable talking about diversion. I think that's a step forward."