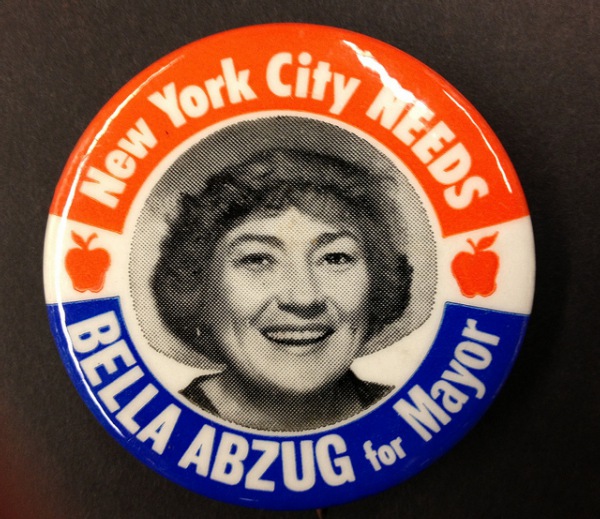

Lessons of 1977: Will Quinn Be The Next Ed Koch or Bella Abzug?

NEW YORK — Once again in 2013, the leading candidate for mayor is a woman: Christine Quinn as Bella Abzug was in 1977.

Quinn has become one of the most powerful woman politicians in the city through her role as City Council speaker. Abzug was a lieutenant to US House Speaker Tip O’Neill. Both had roots in community organizing.

While supporters of both acknowledge they are very different politicians for very different times, once again the most negative articles in the press are about the woman frontrunner.

Abzug was cast in the media as shrill, strident and loud — with one reporter calling her the “Muhammad Ali of feminist politicians” — and portrayed, at least once, as a witch on a broomstick in a cartoon.

While the New York Times has done some soft features on Quinn — showing her at her weekend home with her wife, Kim Catullo, and exchanging ideas with Holland Taylor who is playing Texas woman trailblazer Ann Richards on stage — in March it ran a front-page report on the trouble she has controlling her temper and how she has used her power as speaker to punish Council members who do not accede to her wishes. Some of her supporters have called the story a hit job.

In the first part of our look back at the 1977 race — and what lessons may be drawn from it for this year’s race — we showed how the specific social backdrop of that year shaped a tumultuous field of contenders, while the New York Post as a newly conservative voice in the city worked successfully to shape the outcome. In the end, though, predicting the race before the primary was a gamble.

In this part, we look in particular at Quinn as the frontrunner in the Democratic field, which was complicated in recent days with the entry of former Congressman Anthony Weiner. We also look at the LGBT vote then and now; the Post’s diminished role in the election; the gender gap; and race and the mayoralty.

As Quinn seeks to become the first woman mayor, Quinn owes a debt to Abzug who was the first serious woman candidate to run. But Quinn has governed and run her campaign more as what Ed Koch pitched himself as in 1977 — a “liberal with sanity.” And she surely does not want to end up as Abzug did: fourth in a crowded field.

And with no one issue as yet proving transformative in the race, the 2013 election outcome may prove to be even more unpredictable than the race in 1977.

QUINN AND KOCH

While Quinn is an out lesbian and has been endorsed by national gay rights organizations, Koch’s sexuality was a topic of rumors and innuendo throughout his political career — including the infamous “Vote for Cuomo, Not the Homo” poster campaign run by Cuomo supporters in conservative districts.

A lifelong bachelor, Koch did his best during the 1977 campaign to imply that he was heterosexual, making sure to be photographed holding hands with former Miss America Bess Myerson.

Once in his mayoralty he told an interviewer that he was heterosexual, a proclamation that made the front page of Newsday and was derided by his critics, especially by ACT UP, the then-radical direct action organization that was working to call attention to the plight of people with HIV/AIDS.

Thereafter, Koch resolutely refused to answer questions about his sexual orientation and when confronted with evidence of his homosexuality by the makers of the documentary “Outrage!” walked off the set spewing a barnyard epithet. At his death, even his closest gay friend acknowledged it would have been better if Koch had come out about who he was.

Quinn so identifies with Koch that she led a successful campaign in the City Council to rename the Queensborough Bridge for him—over the objections of some Queens Council Members such as Peter Vallone, Jr., who said they wouldn’t even think of renaming the Brooklyn Bridge.

Koch endorsed Quinn for mayor back in December 2011, telling The New York Times: “I believe that she is center-left, which is what I am. Of all the candidates, Christine is the best able to follow in the steps of Mayor Bloomberg and myself.”

When Koch did pass away earlier this year, Quinn said: “I can remember seeing him on TV when I was a little girl and thinking to myself, ‘If I could ever meet him it would be a dream come true.’ Years later when I was working at the Anti-Violence Project, I was in the midst of a very public battle with City Hall. Mayor Koch called me out of the blue. I had never spoken to him in my life. He told me, ‘You’re doing the right thing. Don’t back down, and call me if I can do anything.’”

“New Yorkers want Daddy as their mayor,” my co-host on “Gay USA,” Ann Northrop, has hypothesized. “They just want someone to take care of them so they don’t have to —and tell them what to do and to give the illusion of strength against everything they fear.”

That may explain some of the tolerance New Yorkers have for zealous policing, like stop-and-frisk that has only now become a serious political issue.

(It may also be why, even this late in the race, there is unabated interest in some quarters for Ray Kelly for mayor — who gets high marks for his performance as police commissioner but is a virtual unknown on the many other issues a mayor has to deal with.)

But it is unclear yet who is wearing the pants in this race — Quinn or one of her opponents — or if the tough stance this year will be about who will keep order or who will restore some balance to the city’s treatment of the middle class and poor.

Allen Roskoff, a gay activist who has been involved in city politics since the era of Mayor John Lindsay and is now president of the Jim Owles Liberal Democratic Club, a left-leaning citywide LGBT outfit, derides Quinn as “the Abe Beame” of this race. “She has effectively been deputy mayor for the last eight years and people want change,” he said.

Mike Morey, spokesman for the Quinn campaign, told the Gotham Gazette that Quinn sees herself as someone in the mold of both Abzug and Koch.

"The passion and fire of Bella Abzug and the everyman common-sense of Ed Koch have both had strong and lasting influences on Christine Quinn's approach to public service," Morey wrote in an email. "She believes in telling the truth, standing by principle, and pushing hard to get things done and she believes that's what New Yorkers want in a mayor."

Quinn has also dedicated a good part of her campaign to trying to distance herself from the mayor she has worked closely with, while not alienating the voters who approve of him.

In particular, she has backed legislation that would create an inspector general for the police department — an idea Bloomberg has decried — and made more pro-union education proposals, such as making school closings a “last resort”--that have been attacked by Bloomberg’s schools chancellor, Dennis Walcott.

Much is different this year, however. Quinn did indeed give Bloomberg the opportunity for a third term in 2009 by extending term limits for him — and herself and her fellow Council members.

But Bloomberg is not nearly as unpopular as Beame was nor has he presided over the same kind of catastrophes as Beame, unless you are looking at how unaffordable the city has become for the middle class and poor — themes being hammered by several of Quinn’s opponents.

Indeed, Quinn herself says “middle class” as often as she can while campaigning. Anthony Weiner got in the race last week touting his middle-class roots and was quickly attacked by Bill De Blasio, the public advocate who also hopes to mayor, for living on Park Avenue now. After 12 years of being ruled by the wealthiest person in the city, the candidates all seem to be banking on the populace wanting someone more like them to govern now.

THE LGBT VOTE THEN AND NOW

While both Koch and Abzug had represented liberal Manhattan Congressional districts and were the lead sponsors of the federal gay rights bill, Abzug was seen as the darling of gay and lesbian voters in 1977.

When a national blow was dealt to gay rights in June of that year with the overturning of a gay rights ordinance in a Miami referendum, thousands of shocked and angry demonstrators in New York marched to Abzug’s home in Greenwich Village as if asking mama to make it better.

Koch appeared at a raucous gay rally in the Village the night of that setback amidst boos for politicians, but his refusal to be dissuaded by that impressed me enough as a 23-year old activist to vote for him that year.

(By 1989, Koch was such a target of anger for AIDS activists that he was shouted down by hundreds of them when he tried to dedicate Stonewall Place in the Village.)

Koch also worked behind the scenes for the gay vote, becoming one of the first major politicians to court the emerging constituency. At that time, most gay and lesbian New Yorkers were not living openly in the workplace and may have identified with Koch’s approach to his sexuality.

This year, Quinn — out, proud, and married to attorney Kim Catullo — enjoys the support of most LGBT groups and donors including the national Gay & Lesbian Victory Fund, but she also is supported by many of the rank-and-file LGBT voters who are looking for the validation of an out lesbian winning such a high office.

The rest of the Democratic candidates also have strong records on LGBT rights.

Albanese cast a critical vote for the 1986 gay rights bill from his conservative Bay Ridge district. Thompson and Liu used the comptroller’s shareholder power to get corporations to adopt non-discrimination policies. Weiner championed LGBT rights in Congress. And de Blasio has a solid record of support and the distinction of having married a woman who was once a leading lesbian writer, Chirlane McCray.

None of the candidates for the Republican nomination profess to be anything but pro-LGBT rights, though George McDonald and Joe Lhota marched in the St. Patrick’s Day Parade that most all Democrats have been boycotting since it excludes Irish LGBT contingents.

THE GENDER GAP

Quinn is holding on to some major feminist support, including from Abzug’s daughter Liz and former Councilwoman Ronnie Eldridge, a liberal lion who was a protégé of Bobby Kennedy, once a special assistant to Lindsay and now hosts “Eldridge & Co.” on CUNY-TV.

Gloria Steinem held out on Quinn until she let the sick leave bill onto the floor of the Council, albeit in a watered-down form after a three-year hold up.

“I wish it could have been faster,” Steinem told The New York Times, while praising Quinn as someone who “has lived a life that allows her to understand the lives of most New Yorkers.”

But Steinem added, “I wish Bella Abzug had been mayor.”

Her daughter, Liz Abzug, said that a Times story on Quinn’s temper reminds her of some of the negative press coverage that her mother Bella endured in 1977, also as “the one woman in the race.”

Veteran Assemblywoman Deborah Glick, who has endorsed Quinn, said: “I thought that the Times front-page piece on Chris [about her temper] had an underlying element of sexism for sure. I am always entertained by young women reporters who say there isn’t sexism. I do think there was an element of it. There are a number of men in office who yell and who threaten and I just found it mind-boggling the level of uneven application of scrutiny.”

Lincoln historian Harold Holzer, who served as Bella Abzug’s press spokesman in Congress, said he was concerned that Quinn was facing the same treatment as Abzug.

“I have never seen so many assaults so concentrated on [Abzug] by so many people in the establishment, including the newspapers,” he said. “The Post would do anything they could to beat her down and make her seem responsible for the Son of Sam, the riots in Brooklyn and the blackout.”

He said Koch attacked her for her “leniency” and belief in a right to strike and the death penalty.

“She and Mario did not believe in a life for a life, and were excoriated for it,” Holzer said. “She went from 36 percent to 16 percent. I’m not ready to play the historian’s role, but I do see Christine Quinn enduring an unfair expectation of having to be everything to everybody and the men and straight candidates are not” burdened with those expectation.

Which brings us to the gender gap, a term, Liz Abzug said, that wasn’t used or polled for until her mother wrote a book about it in 1983.

“Before that,” she said, “the differences in the way women voted was not a discussion point.” Now, the gap between how women and men vote is regularly polled for and marked differences have emerged. The 2012 presidential election saw the biggest national gender gap in history, with Barack Obama winning women by 12 percent and Romney winning men by 8 percent. Obama won the war for women, successfully tarring the national Republican Party as conducting a war on women.

To Liz Abzug, a lot has changed since her mother ran.

“I think a woman — as we’ve seen in many cities — can be a person who is strong enough to break down the violence in an environment,” she said. “I don’t know if it is a better atmosphere for a woman. We’ve seen women in key positions as opposed to ’77 — Speaker of the House, mayoralties in cities big like Houston and small — presidencies internationally. It is more accepted that women can govern from strength, toughness, passion — and heart — and still be commander-in-chief. It is just less of an issue.”

Still, we’ve never had a woman mayor. Carol Bellamy ran on the Liberal line against Ed Koch in 1985, and got beaten badly; former Manhattan Borough President Ruth Messinger was the Democratic nominee in 1997 against Rudy Giuliani and got bested by a 12-point margin. We have had a woman comptroller, Liz Holtzman, Bellamy as Council president, and Betsy Gotbaum as public advocate.

While early polls showed no gender gap for Quinn, the April 15-18 Quinnipiac poll had her leading with 31 percent of women and 24 percent of men with Anthony Weiner polling at 12 percent of women and 20 percent of men, a gap most would attribute to his fame for sending erotic pictures of himself to women strangers. A gap had emerged.

But by the May 22 Quinnipiac poll, Quinn had less of a gap with 23 percent men for her and 26 percent of women, while Thompson fared better with men by six points (14-8 percent) and Weiner with men by four (17-13 percent). John Liu, who faded to 6 percent overall in the current poll has the support of twice as many women (8 percent) as men (4 percent).

THE NEW YORK POST

While Koch would tell you that Rupert Murdoch made him mayor along with his campaign manager David Garth, it is unclear if Murdoch’s New York Post still has that kind of power even though it has already attacked Quinn, labeling her as “Mayor Dracula” based on a vampish New York magazine cover.

One headline says she is going for the “the Bella donna look” in what may have supposed to have been a reference to Bela Lugosi who played Dracula in the 1930s, but also summoned up the memory of Bella Abzug.

The paper has also gone after de Blasio for revelations that his wife had been a lesbian and Liu for the misdeeds of his aides. And they never tire of making front-page Weiner sex jokes.

In 1977, the Post aggressively went after Abzug over her pro-labor stances. According to historian Chris McNicle, Abzug sealed her fate when she backed the right of police and firefighters to strike just days before the city was blacked out and riots terrified whole neighborhoods. “That was bad politics in a city preoccupied with law and order,” McNicle wrote in “To Be Mayor of New York: Ethnic Politics in the City.”

It is hard to tell yet who Murdoch or the rest of the city’s more establishment sectors (real estate and finance) want for mayor, but they have ways of letting their thoughts be known through attacks in the media and by where they spread their donations.

A big difference this year is that Murdoch is losing his grip on his media empire due to scandals in Britain.

And money will play less of a role with most of the candidates in the campaign finance system that matches the donations they get 6-to-1 but limits their spending at each stage of the race. No one but billionaire John Catsimatidas is self-financing.

So far the biggest independent expenditures have come from left-leaning labor and animal rights activists www.NYCityisNot4Sale.com doing their best to define Quinn in a negative way before she can run ads defining herself. The strategy has echoes in the way independent supporters of Obama painted Romney as an out-of-touch vulture capitalist while Romney was tied up fighting for the Republican nomination last year and unable to free up the funds to answer those attacks.

RACE AND THE MAYORALTY

While we did get a one-term black mayor in David Dinkins at a time of great racial unrest in 1989 after what was perceived as an era of racial polarization under Koch, Dinkins lost to Giuliani in 1993 partly because Dinkins was seen as not being able to control the racial unrest in Crown Heights that year.

We have never had a Latino mayor, despite Bronx Borough President Fernando Ferrer coming close to winning the Democratic nomination in 2001 against Mark Green, who went on to lose a squeaker to Bloomberg in the chaotic aftermath of 9-11. Ferrer came back to win the Democratic nomination in 2005, but lost to Bloomberg big.

The people of color in this year’s race are Thompson, who came within 4.4 points of knocking off Bloomberg in 2009 despite being up against another $100 million Bloomberg campaign; and Liu, who despite the shadow of convictions of some of his top campaign aides, has a solid base in Asian communities and deep ties to other communities of color and labor. (Thompson also enjoys close ties to the city’s Orthodox Jewish community.) And there is Carrion, who left the Democratic Party and sees a path to victory as a Republican and as the Independence Party nominee where the current Quinnipiac poll has him pulling 12 percent on that line—obviously not enough to win but more than enough to be a factor in the fall.

So far, the biggest racial issue in the contest is where the candidates stand on the stopping and frisking of hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers each year, most of them youth of color. Positions vary from Liu, who wants it banned, to Lhota who wants it maintained with the others on a scale in between.

AN UPREDICTABLE RACE

Veteran Times reporter Sam Roberts wrote last week about how the current mayoral race puts him in mind not just of the 1977 contest, but the one in 1973 when there was no incumbent, calling them all “heavily contested” and “unpredictable.”

While this year Anthony Weiner has gotten in two years after a scandal, Roberts noted that, in 1973, Congressman Mario Biaggi was the frontrunner until it was revealed that he had taken the Fifth Amendment in a corruption trial. That let Beame get into a runoff with Badillo who undid himself by referring to Beame as “a malicious little man” — the kind of misstep in a long campaign that can derail one’s prospects.

Roberts wrote that Beame was supposed to sit out the 1977 race after presiding over the fiscal crisis and endorse Manhattan Borough President Percy Sutton, an African American. And he credits Gov. Hugh Carey with getting Cuomo the Liberal line to the great consternation of Beame.

Political consultant Hank Sheinkopf told the Times regarding this year’s race: “Now we have everybody splitting in a non-ideological environment, and that means anything can happen.”

The biggest lesson from 1977 is that this 2013 race, with all its permutations and combinations, is indeed impossible to predict. A large field makes it harder for voters to focus on what their choice is. And New York City polls have a history of being notoriously wrong.

The primaries are especially unpredictable, but on the Democratic side — unless Quinn or a rival pulls down 40 percent — it will be followed by a one-on-one runoff. The polls currently have her vanquishing her chief rivals in such a runoff, but it is early and the electorate has not focused on the alternatives.

If 1977 is an indicator, no matter who is on what line, the voters of New York City in the end won’t be looking at party affiliation but at the two candidates who have proved themselves most viable and choosing between them.

Right now, the relatively unknown Lhota loses 13 to 61 percent against “the Democratic candidate” according to the latest Quinnipiac poll. But let’s remember that the eventual 1977 winner, Ed Koch, was at about 4 percent in the polls at this stage. And, in 2001, Mike Bloomberg, the eventual winner, was polling at about 25 percent in the early stages.

And the candidates are mostly arguing about policing (the merits of stop-and-frisk), education (keep mayoral control or share governance more), affordable and public housing, and term limits (right or wrong to have extended them).

It may be that the issue that will define the candidates for the voters may not have come to the fore.

Andy Humm is the co-host of the weekly Gay USA cable TV show, a contributor to Gay City News, and a former city Human Rights commissioner.

Loyal Election Machine Could Help Disgraced Politician Win A Council Seat

NEW YORK — With Vito Lopez having unceremoniously resigned from the state Assembly where he once lorded over the powerful housing committee, the career politician has turned his attention to getting elected to the City Council. And he just might succeed.

That’s because the two other candidates in the race for the 34th district — one of whom is being backed by Council Speaker Christine Quinn — could end up appealing to the same pool of voters, potentially splitting them and handing Lopez a victory.

Perhaps more importantly, the disgraced former assemblyman, who is accused of sexually harassing several women, will undoubtedly call on his deep, established base of neighborhood support in the district to get out the vote on Election Day.

“He’s a wonderful man, a wonderful politician,” said Lalo Burgos, 73, who lives in the district and runs a barbershop near Maria Hernandez Park in Bushwick. And he said Lopez takes care of residents. "That’s all that matters.”

John Mollenkopf, a professor at the Center for Urban Research of the CUNY Graduate Center, said that community support could make all the difference for Lopez.

"He runs an old-fashioned type of operation that’s very much based on loyalty," Mollenkopf said. "This will be a test of that loyalty.”

It also doesn’t take many votes to win in a Council primary: Diana Reyna, the term-limited Councilwoman who holds the seat, won in 2009 when there was no mayoral race, with 3,865 votes.

Last week’s release of an embarrassing state ethics report detailing allegations of Lopez’s misbehavior with female staffers led the 71-year-old legislator to announce his retirement at the end of the legislative session in June while also proclaiming his innocence.

The announcement was met with cries for an immediate resignation and movement within the Assembly to push him out of office.

Lopez then sped up his timeline. By Monday morning, his nameplate was taken from his office door and his Assembly web page was taken offline.

A second investigation, led by Staten Island District Attorney Dan Donovan as a special prosecutor, could find no basis for bringing criminal charges against Lopez. It did, however, call into question Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver’s role in a secret taxpayer-funded settlement for two of Lopez’s former staffers.

“I have maintained my innocence throughout this matter and I believe no criminal investigation should ever have been conducted,” Lopez said in his statement on May 17 announcing his resignation at the end of June before he was faced with the possibility of expulsion and resigned on Monday.

He said that he would focus on the Council race. “I expect to run a vigorous campaign on the issues facing the citizens of my community and hope to continue to serve them as a member of the City Council,” he said. “I believe that the voters of the community should decide who should represent them.”

Lopez and his representatives didn’t respond to requests for comment for this story.

The longtime politician’s deep ties to the Bushwick, Ridgewood and Williamsburg neighborhoods are rooted in his years as chair of the Assembly’s housing committee, through which he steered state money to his district for low-income housing and a popular senior center he created.

Founded in 1973, the Ridgewood Bushwick Senior Citizens Council, was one of the main beneficiaries of the money that Lopez made sure flowed from Albany to his district.

“He’s got a base of support through his social services that’s going to vote for him no matter what,” said Doug Muzzio, a political science professor at Baruch College.

And that, Muzzio says, could make the difference in how much the sexual harassment scandal plays into the Council race.

“In the ‘should’ world, this should kill him," Muzzio said. "But the ‘is’ world is another story.”

Muzzio said a split between the other two candidates could hand Lopez the spot on the Democratic ticket, tantamount to election in November. “It’s politics 101. If you want to win — split the competition,” Muzzio said.

Lopez lost some of his support when news leaked last year that Lopez had been accused of sexual harassment by several former female employees. Lopez, who had represented the 53rd Assembly District since 1984, was censured and stripped of his housing committee chairmanship — the very seat of power which he used to funnel funding to his constituents.

He also lost his seat as the Kings County Democratic Party chair, which he took over in 2006 from disgraced former Assemblyman Clarence Norman Jr., after he was convicted of taking illegal campaign contributions.

Well before the ethics commission report was released, anti-Lopez protesters gathered on a soggy April afternoon around the corner from a posh Williamsburg restaurant on the water.

Organized by local members of the National Organization for Women and a progressive Democratic club, the New Kings Democrats, 20 or so protesters shouted from the sidewalk as cars drove in for Lopez’s first fundraiser for the Council race.

“It’s outrageous that someone who’s been accused of sexual harassment has the chutzpah to run for City Council,” said Lincoln Restler, a New Kings Democrats member and former Brooklyn district leader. Created in 2008, the reform club has spent years organizing against Lopez and endorsing candidates to subvert his influence across the borough.

One of those candidates is Antonio Reynoso, who is also a member of the New Kings Democrats. But he’ll also have to face Tommy Torres, 40, in the district’s Democratic primary.

Reynoso is the chief of staff to the 34th district's term-limited Councilwoman Diana Reyna, a former top aide to Lopez turned bitter foe. The 30-year-old Brooklyn native grew up in Williamsburg’s South Side before leaving for college upstate.

By the time Reynoso came back to Brooklyn, he knew he wanted to be in politics even if he didn’t know where to start. He said he went out one day with two resumes: one for Reyna and one for Lopez.

Lopez’s office was closed that day; Reyna hired him. “God steered me in the right direction,” Reynoso said.

Reynoso makes no effort to hide his disdain for Lopez, especially in the wake of last week’s report. “He should resign immediately and step away from serving public office,” he said. “There’s no remorse. There’s no realistic understanding of what he’s done. And that’s the biggest crime.”

Reynoso isn’t the only one upset by Lopez’s bid for City Council, and he’s already received powerful backing for his run. Speaker Christine Quinn launched a “Women for Reynoso” campaign, naming Reynoso as the only viable option for the 34th District.

“We must ensure that Vito Lopez never sets foot in City Hall,” Quinn said in a statement.

Reynoso has also been endorsed by another Democratic progressive in the mayoral race, Bill de Blasio, and has gained the support of major unions — which Muzzio said will be a key factor in the race. To beat Vito, he said, “You need organizational muscle.”

To date, Reynoso has raised around $86,000 for the race. While Lopez has managed to net approximately $38,000 for his City Council run, The New York Post has already reported that Lopez might be able to roll over some of the more than $1 million he has in state campaign coffers.

Meanwhile, Torres, the third candidate for the Council seat, has raised close to $23,000. A public school teacher and athletic coach, Torres grew up in Cooper Park Houses, one of Greenpoint’s public housing developments.

Torres stayed in the borough for college, going to St. Francis College in Brooklyn Heights on a baseball scholarship. He followed that up with a master’s degree in education from Mercy College in Westchester County, which Torres said wouldn’t have been possible without the city’s public education program.

“I took advantage of the public schools,” said Torres over the phone after coaching a baseball game. “I came back to continue the good work.”

For either Reynoso or Torres to come out on top, they need to beat Vito’s ongoing popularity around the district. Throughout Bushwick, Lopez’s current constituents still say that they care more about his generosity than the allegations against him.

Caesar Bettencourt, 72, stood near a stoop along St. Nicholas Avenue as he defended Lopez.

“I think certain people are trying to make trouble for him,” said Bettencourt, a regular at the local senior center. “I think it’s all a setup. It’s politics.”

An earlier version of this article originally appeared in a NYCity News Service multimedia project entitled "Bushwick Beyond the Brand," which examines continuing changes in the neighborhood as the Bloomberg era comes to an end.

Two Pivotal Elections: What The 1977 Mayoral Race Can Tell Us About 2013

NEW YORK — Seven Democrats want their party’s nomination for mayor and the frontrunner is a woman who would be the first of her sex to lead City Hall. Two Democratic candidates of color may eat into each other’s bases. Credible candidates on the Republican side have a good shot at a win. Minor party designations could play a major role come November. The New York Post is angling to have a big say in who gets elected.

{sidebar id=18 align=right}

The 2013 mayoral race? No, the 1977 free-for-all — the last big, multi-candidate election for mayor where almost nothing was predictable.

A look back at the contest that marked a shape-shift in the city over 35 years ago demonstrates how much has changed in both our politics and our social and economic make-up since then.

But to Kenneth Sherrill, professor of political science at Hunter College and was elected Democratic District Leader in 1977, it is the voters who have changed most of all.

“A lot of the voters of that election are dead, the city is much less white, the make-up of white ethnics has changed, there was no Asian American vote then, and the immigrant population wasn’t what it is now,” he said. “Today there isn’t the bankruptcy or crime that there was then, so the inferences about what, for instance, the African American or Jewish vote would do now are very different.”

A TUMULTUOUS TIME IN POLITICS

The year 1977 was a tumultuous and pivotal one in New York City politics.

It was best remembered for a steaming hot July blackout that was followed by looting and arson, the “Son of Sam” murders that had the city on edge, the rise of Rupert Murdoch’s transformation of the once-liberal New York Post into a sensationalistic rightwing Brit-style tabloid, and the first Yankees World Series win under owner George Steinbrenner.

The Bronx was burning — figuratively and literally — and the city was still simmering from Republican Gerald Ford initial denial of a bailout two years earlier.

The year 2013 is no less pivotal and tumultuous for the city’s politics.

The longtime incumbent mayor, Michael Bloomberg, who was not supposed to have a third term and got one after changing the term limits law with the help of the City Council and Speaker Christine Quinn, is about to depart after overseeing a prosperous period of growth and development — at least for those at the top — that had the business elites cheering.

As his term winds down, the mayor is warning against a return to “the bad old days,” trying to answer the rising indignation of a coalition of progressives, people of color and civil rights advocates who have called attention to what they say have been overly aggressive police tactics during Bloomberg’s tenure, such as stop-and-frisk and the surveillance of Muslims.

Even without the public debate over police tactics, there would be enough to shape the mayoral election: school reform and whether to continue mayoral control; rebuilding after Superstorm Sandy and responding to future disasters; and the erosion of the city’s middle class and the inequality gap that has widened over the past decade.

1977: A Stellar Field Of Candidates

In 1977, despite presiding over the city’s economic meltdown, Democratic Mayor Abraham Beame — who had the added liability of having been the comptroller when the city’s books were coming apart at the seams — ran for re-election.

In addition to Beame on the Democratic side, two liberal Manhattan Congress members jumped in — the relatively unknown Ed Koch and the famous Bella Abzug, who was coming off a razor-thin primary loss in 1976 to Daniel Patrick Moynihan for the Democratic nomination for US Senate.

Manhattan Borough President Percy Sutton also got in the race — the first black with a credible shot at becoming mayor — but so did Herman Badillo, a Congressman from the Bronx who had served as Bronx borough president and was the first Latino with a serious chance of winning the top spot in City Hall.

The longest-shot Democrat in 1977 was the former chair of the City Club of New York, Joel Harnett, who got on the primary ballot but would only go on to garner 1 percent of the vote.

And last but by no means least there was Mario Cuomo, Gov. Hugh Carey’s secretary of state, whose claim to fame then was mediating a dispute for Mayor John Lindsay over a public housing project planned for upper middle class Forest Hills.

It was Carey, one of the architects of the bailout for the city, who pushed Cuomo to run for mayor.

There was a Republican primary in 1977, too, with liberal state Sen. Roy Goodman of the Upper East Side, heir to the Ex-Lax fortune, squaring off with popular conservative radio talk show host Barry Farber.

Minor parties played a key role in 1977 as they very well may this year. Farber lost the Republican nomination to Goodman but had the Conservative Party line. And Cuomo won the Liberal Party line.

The conventional wisdom made Abzug, who died in 1998, the frontrunner for the Democratic nomination — based on her name recognition and strong showing for US Senate — and all the talk was about who in the crowded field would end up in the runoff with her after the initial primary vote.

Legendary journalist Doug Ireland, who is still writing today, managed Abzug’s Senate campaign but tried to discourage her from running for mayor and to instead try again for Congress, which he said he felt was more suited to her talents.

“I told her she wasn’t prepared and it would kill her chances for future office,” he said. “It Stassen-ized her,” he said, referring to Harold Stassen, a wartime Minnesota governor who ran for the Republican nomination nine times starting in 1948.

Abzug lost two subsequent U.S. House races on Manhattan’s East Side in 1978 and in Westchester in 1986. She also tried to get her old West Side seat back in 1992 when Ted Weiss died, but was beaten in a party convention by Jerry Nadler, who still holds the seat today.

A Violent Summer Shaped the 1977 Race

The 1977 race was very much a creature of external events, primarily the “Son of Sam” murders that had begun the previous year, with most victims young lovers in parked cars, and the arson and the chaotic aftermath of the July 13 blackout.

As Sewell Chan of the Times wrote on the 30th anniversary of the blackout: “1,000 fires were reported, 1,600 stores were damaged in looting and rioting and 3,700 people were arrested. Neighborhoods from East Harlem to Bushwick were devastated. The authorities later estimated that the total cost of the blackout exceeded $300 million.”

While these events by themselves might not have been enough to turn voters away from the more liberal candidates — particularly Abzug — the sensationalizing of these events by the New York Post under its new owner Mudoch were.

As Jack Doyle wrote in “Murdoch NY Deals: 1976-77,” the Post blackout headline was “24 HOURS OF TERROR.” He quotes Pete Hamill of the Daily News writing, “Something vaguely sickening is happening to that newspaper, and it is spreading through the city’s psychic life like a stain.”

When Murdoch decided to endorse Ed Koch, he was running at about 4 percent in the polls and was a virtual unknown citywide.

While Koch might have been the bachelor congressman from Greenwich Village — and was gaybaited by some in the Cuomo camp with “Vote for Cuomo, Not the Homo” posters in conservative precincts — Murdoch picked up on him as one of the only pro-death penalty Democrats who was willing to take up the banner of “law and order.”

“There are many reasons why Mr. Koch became the next mayor,” wrote Joyce Purnick, a reporter for the Post during that election, in a story a few years ago in the New York Times, “but I will always believe that the blackout separated him from the pack.”

Koch also hired legendary political consultant David Garth, who had guided John Lindsay to re-election in 1969 and went on to make Rudy Giuliani and Mike Bloomberg mayors. Garth's famous winning ad slogan for Koch was: "After eight years of charisma and four years of the clubhouse, why not try competence?” -- digs at both Lindsay and Beame respectively. In 2010, the NY Times wrote, "Just by signing on with Mr. Koch, Mr. Garth had conferred instant credibility on his fledgling campaign. 'Without him,' Mr. Koch said, 'I would never have been mayor.'"

Koch was also helped by an innovation taken for granted now — overnight polling. The Fix reported in an article titled "Ed Koch, polling pioneer" that polling data in 1977 had to be filtered through university computers, a process that took days. Garth hired Mark Penn, then still a college student, and his pal Doug Schoen, to do their polling, and Penn built his own computer to be able to process their polling data immediately — such as testing Koch's famous slogan for impact.

While Abzug is generally regarded as the most liberal candidate in the race — Ireland calls her “the first radical elected to Congress since Vito Marcantonio” (the East Harlem Communist elected as a Republican to the House in 1934), Badillo was also running to the left as “a champion of the poor,” Ireland said, “and then he went on to work for Koch and Giuliani who were declared enemies of the poor."

To help Koch, the Post focused its negative coverage on Abzug and Cuomo.

About two weeks before the primary, a Times/CBS News poll had Beame and Abzug at 17 percent each, Cuomo at 14 percent, Koch with 12 percent, Sutton with 9 percent, and Badillo with 7 percent. It was anybody’s ballgame.

When the votes were counted on Sept. 8, 1977, Koch led the pack with 19.81 percent followed by Cuomo, who had the Times’ endorsement, with 18.74 percent, putting them in the runoff triggered by no one getting 40 percent.

In third was Beame with 17.98 percent and early frontrunner Abzug finished out of the money with 16.56 percent. Sutton got 14.42 percent, Badillo 10.97 percent, and Harnett 1.53 percent.

Koch beat Cuomo in the runoff for the Democratic nod 55 to 45 percent, and Cuomo ran hard on the Liberal line in the general election losing 50 to 41 percent with Goodman the Republican and Farber the Conservative getting 4 percent each.

How did Koch win?

“One, I lost the black vote because they came and asked for a deal — a commitment for a black vice mayor,” Mario Cuomo told the Gotham Gazette. “I didn’t think that such a deal was a good idea. Badillo asked for same thing. I told him no. Meade Esposito, the Democratic boss in Brooklyn, asked for a deal and I said no. That was the Koch victory. Nothing illegal or terrible for them asking for it, I just wasn’t comfortable in giving it.”

Koch did make those deals to get elected, but they didn’t work out for him in the long run. He appointed Basil Paterson, a Harlem leader and father of former Gov. David Paterson, and Badillo as deputy mayors. But neither lasted much longer than a year — Paterson becoming secretary of state under Carey and Badillo quitting in a dispute with him over his failure to deliver for the South Bronx. The deals with boss Esposito, Queens boss Donald Manes and Bronx boss Stanley Friedman didn’t catch up with Koch until his third corruption-scarred term.

Role of Minor Parties

Barry Farber, still a conservative radio talk show host, said there was one big difference between 1977 and 2013: “There was a meaningful Liberal Party and a meaningful Conservative Party in ’77.”

Indeed, though Farber ended up with 4 percent in the general election in 1977, “there was a scenario for me to win on the Conservative line and doing an insurgency on the Republican line if the Democrats had lived up to their habits and nominated the leftmost candidate” — Abzug.

In Farber’s view, he was preempted by conservative Democrats.

“Ed Koch took the biggest broad jump in history and adopted the social welfare policy of Genghis Khan. He didn’t edge toward right. He came out as though there had never been a leftist,” he said. “Cuomo was considered the second most conservative and he finished second. Beame, the incumbent, was the third most conservative” and he finished third with Bella fourth.

The Liberal Party hasn’t enjoyed automatic ballot status since Andrew Cuomo had their line for governor in 2002 and then refused to campaign and opposed the Democratic nominee Carl McCall, having already dropped out of the Democratic primary.

But this year, the Liberals, which were the key to Rudy Giuliani’s two mayoral wins, have given their line to grocery store chain billionaire John Catsimatidis who wants to be the next Bloomberg.

The Working Families Party, which supplanted the Liberals, has yet to designate a candidate and may be unable to settle on one in the crowded primary given their complex, consensus-building nomination process.

The Independence Party, which gave Bloomberg the minor party help he needed to become mayor three times, has designated former Bronx Borough President Adolfo Carrion as their nominee.

Carrion and Catsimatidis along with former Giuliani Deptuy Mayor and Metropolitan Transportation Authority Chairman Joe Lhota and homeless advocate George McDonald are running for the Republican nomination with Lhota the early favorite — though no poll has come out since his labeling of Port Authority police as “mall cops” got a lot of pushback from his base and he had to apologize.

The Conservative Party, long led by Mike Long, has not yet made a pick, but will before the September primary.

Carrion doesn’t want his nomination, but the others in the Republican primary do and Long will pick one of them (despite some of their socially liberal positions) because he fears the leading Democrats “would really take the city backwards a lot of years,” he told Crain’s.

2013 a Different Time

What has changed since 1977? To Bill Lynch, it is the voters who have changed.

“The difference is the voters have changed drastically,” said Bill Lynch, a Harlem-based political consultant who managed David Dinkins’ mayoral campaigns and served as his deputy mayor. People of color — once called “minorities” — have became the majority.

But the city has also become what Bloomberg calls “a luxury product,” which in recent years has attracted the people of means who fled urban America in the 1970s but have returned to New York City en masse, driving real estate to stratospheric levels while the market still languishes in most parts of the country.

“One lesson of 1977,” said Sherrill, “is that once you have a certain number of candidates, it is impossible to go over 40 percent, and it is hard to predict who will be the top two. The other lesson given who ended up in the runoff is never to underestimate anybody. There were some people who predicted Koch-Abzug, but nobody predicted Koch-Cuomo.”

This year, the Democratic field is as crowded as it was in 1977 and gaming out who will be the top two in the expected runoff following September’s primary is anybody’s guess. Three seem to be vying for most liberal — Public Advocate Bill de Blasio, Comptroller John Liu, and former City Council Member Sal Albanese — while former Comptroller and 2009 Democratic candidate Bill Thompson has moved toward the center.

Quinn is to Thompson’s right, though even she is tacking left with proposals to oversee the police department more closely after she agreed to back a bill that would impose an independent monitor over the NYPD, and finally giving in on a paid sick leave bill — albeit in a much watered-down version.

If former Congressman Anthony Weiner jumps in — and he comes in second to Quinn in recent polls — he would fit somewhere between the left candidates and Thompson.

Sherrill said that for all the help Koch got from the Post, the election came down to a message that resonated with voters. And, so far, he said he had not heard a message from any of the 2013 candidates that resonates.

“You go to the boroughs outside Manhattan and you hear about an unresponsive government that took care of the affluent on Wall Street and did not help them,” Sherrill said. “I think a candidate who makes an appeal to frustrated working-class people that he or she will stand up for against the relatively well off who saw a much more rapid recovery can do very well in the parts of the city that were devastated and haven’t bounced back. With the rising inequality, there is a strong sense that no one is looking out for ‘people like me.’ I would not be surprised to hear Anthony Weiner take that up. I would not be surprised if the election turned on personality and style more than the issues. I think an angry candidate can do very well, I’m afraid.”

Andy Humm is the co-host of the weekly Gay USA cable TV show, a contributor to Gay City News, and a former city Human Rights commissioner.

UPDATE: This version is updated with more information on Koch's 1977 campaign.