Cuts Burn Fire Department

A proposal to slash 20 fire companies from the Fire Department's ranks does more than irk firefighters.

It burns them.

A crowd of elected officials and firefighters gathered in front of a Long Island City firehouse Friday to slam the Bloomberg administration's proposal to strip the department of 400 firefighters.

One of those firefighters was Bob -- a 23-year veteran of the department who did not want to use his last name for fear of repercussion. Bob has fought blazes with the rest of Queens' Hook and Ladder 116 for nine years. Cutting almost 7 percent of the city's fire companies now, Bob said, would be "crazy."

"It's more dangerous for the community and me," Bob said of the potential closures, which he contends will add catastrophic seconds to the department's record-low response time. "Another 30 seconds, a minute, forget about it."

Overall, the Bloomberg administration is proposing to cut $27 million from the Fire Department in fiscal year 2011 -- equal to about a 1.7 percent cut in controllable city funds. To close a budget gap, the administration has proposed to reduce the number of firefighters per engine, get rid of the so-called outdated street fire alarm boxes and, most controversially, close 20 fire companies.

But firefighters, city and state politicians as well as labor leaders are ready to bring the heat on the administration. They say the city cannot afford to lose any firefighters, especially in light of this month's bomb scare in Times Square. If the mayor cares about public safety and is willing to abandon cuts in police officers, they say, firefighters should be held harmless too.

"We're like the Marine Corps for the city," said Fred Sutton, a retired firefighter from Ladder 116 on Friday. "Cops are like the army."

Slashing Engines

The administration counters: There have to be cuts somewhere.

"'We've been forced into a position that we have to make choices that no one wants to make and they're very unpopular," said mayoral Spokesperson Marc LaVorgna of the fire company cuts. If the administration didn't make these decisions, then the city's fiscal situation could end up like Albany's, LaVorgna added.

The administration's proposal would aim not to close firehouses, which typically hold more than one fire company, such as a ladder and an engine company.

Critics of the cuts say the administration should look elsewhere to trim the fiscal fat. Comptroller John Liu argues the fire company closures are small compared to the entire city budget -- in fiscal year 2011 the closures would save about $5.6 million. The city could cut back on unnecessary contracts to save the engines and ladders, he said.

Others attribute the administration's proposals to fear mongering.

"This is the administration trying to scare the crap out of New Yorkers," said Assemblymember Michael Gianaris at Friday's rally in Queens.

The administration has not said what companies could close, and it does not have to until 45 days before the budget deadline of June 30, according to a mayoral spokesperson.

When asked how the department would select fire companies to close, a Fire Department spokesperson e-mailed: "The criteria would be, as always, to allocate our available resources as best we can to protect the citizens of New York City."

In anticipation of the cuts, labor officials are looking to the mayor's proposal from last year, which would have cut 16 fire companies (it was reversed by the City Council). Many think those same companies, which included a company on the South Shore of Staten Island, one on City Island in the Bronx and another in Bushwick, Brooklyn (to name just a few), will end up on the chopping block again.

The loss of 400 of the city's 11,000 firefighters under the proposal would be done through attrition, according to mayor's budget proposal.

The last time fire companies were closed was in 2003. Six engines were shuttered, including one at the firehouse in Long Island City.

Other Alternatives

Outside ladder 116 on Friday, several council members said they wouldn't take closures as the answer.

"The mayor found $100 million to secure our security services," said Councilmember Elizabeth Crowley, the chair of the council's Committee on Fire and Criminal Justice, referring to the mayor's promise to save cops from budget cuts. "Well, the Fire Department is our security services."

For now, fire, state and council officials aren't looking to compromise, and they are using the recent scare in Times Square to bulk up their argument.

"We are prepared and trained to do the unimaginable, respond to a biological, chemical, nuclear or radiological attack. We can't do that from a closed firehouse," said Steve Cassidy, the president of the Uniformed Firefighters Association. "Last Saturday was the reminder that New York City remains the number one target for terrorists. I am not sure the mayor got the message."

In terms of need, fire officials say the city now has fewer fires than in years past. In 2009, the department responded to 43,677 fires compared to 51,563 in 2002. But, labor officials argue, the department has taken on other responsibilities, like building inspections resulting from the fire at the Deutsche Bank building in 2007. In 2002, the department responded to 374,949 non-fire incidents. In 2009, they went to 429,541 incidents -- an increase of 14.6 percent.

All of that takes manpower, said labor leaders, and the city can't lose any of it.

When asked whether fire unions would consider contributing to health care costs or other benefits to save fire companies, union officials scoffed.

"Fire protection should not be paid for by firefighters," said Capt. Al Hagan, the president of the Uniformed Fire Officers Association. "We feel that fire protection should be paid for by the people, and we think the people have no objection to paying for fire protection."

Council, Courts End the 'Tenant Blacklist'

The term "blacklisting," usually associated with 1950's McCarthyism, has taken on a new meaning. The blacklisted in 21st century New York have been people applying for apartments whom property owners deem undesirable as tenants. In an effort to limit this practice, the New York City Council in March, building on previous court cases, enacted the Tenant Fair Chance Act.

While credit checks are well known, most New Yorkers do not realize that some companies buy landlord-tenant filings, harvest court histories and sell them to landlords. The endgame is for landlords to learn whether the apartment-seeker had an in-court dispute with a prior landlord.

Tenant screening agencies, as the companies are known, may supply information about credit, character, reputation and personal characteristics, but the new law's emphasis is on "history of contact with any court... [and reports] used for the purpose of serving as a factor in establishing a consumer's suitability for housing."

The Legal Background

In the case of White v. First American Registry a class-action was brought in federal court in Manhattan against the nation's largest tenant screening agency. In his ruling, Judge Lewis Kaplan of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York noted that landlords are all too willing to use such "consumer reports" as a blacklist, "refusing to rent to anyone whose name appears on it regardless of whether the existence of a litigation history in fact evidences characteristics that would make one an undesirable tenant."

The judge went on to say the practice of seizing upon the availability of Housing Court filings helps "to create and market a product that can be, and probably is, used to victimize blameless individuals. Tenants and lawyers in that case won more than $2.9 million.

While everyone agrees landlords have a right to know who will be living in their buildings, and that they should do some checking, Kaplan agreed with tenants that the records obtained and sold by screening agencies are unreliable. As Supreme Court Judge Barbara Kapnick wrote in the later case of Dawn Weisent v. Subaqua, "regardless of whether or not a tenant prevails in the Housing Court, his or her name may appear on the 'blacklist.'"

Limited Information

The Housing Court records that are bought and sold show merely that a proceeding was commenced, not what ultimately happened in the case, making the information incomplete or even inaccurate. The records the screening agencies receive from the court show a proceeding was brought -- for example, Landlord v. Tenant -- but give no other information. Because of the limited facts, the case might not even involve the tenant in question, but someone else with the same name, giving a false impression of a potential tenant’s history with a landlord.

The records also do not reveal, for example, that a tenant might have previously withheld rent due to dangerous housing conditions. Instead, they simply show that the tenant was a defendant in a lawsuit. The records also will not reflect that a Housing Court judge might have dismissed the landlord-tenant proceeding, finding that it was baseless, or deciding after trial in favor of the tenant. In other words, the mere fact that there was a proceeding in an apartment related dispute brought to court could be used against a person trying to rent an apartment -- even if it is the wrong person.

The Council's 'Fair Chance'

The Tenant Fair Chance Act, which was introduced by Manhattan City Councilmember Daniel Garodnick and co-sponsored by 17 other members, goes into effect this summer. It intends to let potential tenants know if screening agencies are being used and what they have reported about them, especially if adverse information has led to denial of an apartment.

In introducing the bill, Garodnick said, "Tenant screening reports are one of the most powerful tools working against renters today, and yet they are almost completely unregulated."

Under the new law, the tenant who is spurned is entitled to a copy of the report and the opportunity to make any corrections. The law states, "Every tenant or prospective tenant may dispute inaccurate or incorrect information contained in a tenant screening report directly with the consumer reporting agency."

A violation of the Tenant Fair Chance Act law “shall be subject to a civil penalty of not less than $250 nor more than $700 for each violation.” Other penalties, including criminal prosecution, also are available.

Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court Justice

Police Need New Approach to Deal with the Mentaly Ill

In 2008, New York City police arrived at the Bedford Stuyvesant home of Iman Morales, a 35-year old man with a psychiatric diagnosis. Distraught and naked, Morales had climbed out the apartment window and onto a storefront ledge. The encounter ended when one of the officers aimed his Taser at Morales, who then plummeted onto the concrete 10 feet below and suffered a fatal head injury.

The officers on the scene were, like all New York Police Department officers, armed with guns, but no proper training or tactics to diffuse a situation with a person with mental illness. Later that week, the police lieutenant who gave the order took his own life.

In response to Morales’ death, Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly responded by saying the NYPD would increase training for police officers -- but the change was purely in the quantity of instruction, not the quality. Kelly said the additional training would be "in essence, going over the training they've received."

An Inadequate Response

Going over the basics is not enough. There continue to be a shocking number of incidents where the New York City police have encountered a person in a state of psychiatric crisis, and rather than de-escalating the situation, their untrained reactions and poor decisions have left the person injured or even dead.

The police department's current policing practices are at best inadequate, and at worst ineffective. A refresher course on an insufficient model does not change direction and certainly has not prevented people with mental illness from being criminalized or killed. A true shift in policy is needed, with the police spending more time with people with mental illness so that they can be treated with the dignity and respect that they deserve.

Sadly, that has not happened, and the Morales encounter remains not far from the norm. Two years after his death, the New York's policing model still includes no distinct response system for its officers to safely interact with people with psychiatric disabilities when they are in a state of crisis.

Olga Negron, Morales' mother, still lives with the loss of her son. She says that she misses him "so much -- my heart hurts everyday." She knows that her son’s death was avoidable -- if the police department only knew how to protect both New York's psychiatrically disabled and the many police officers who interact when them on a daily basis.

What Other Cities Do

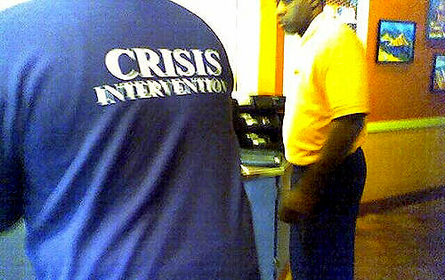

Luckily there is a solution -- for Negron, and for the New Yorkers with psychiatric disabilities. Eighty cities and counties around the country have taken on new policing models to make interactions between police and people with mental illness safer for all involved and reduce arrests. Crisis Intervention Teams connect residents to social services early in cities large and small around the country -- including Los Angeles, Chicago, and Houston -- and keeping people who need treatment out of jail and prison.

Rather than killing or injuring people with mental illness, Crisis Intervention Teams offer an opportunity to help provide treatment and a therapeutic environment to individuals in need of support. While New York's prison population is decreasing, the percentage of prisoners with mental illness has risen. The Crisis Intervention Teams provide a humane solution to the unjust punishment of people with mental illness.

Crisis Intervention Teams require police officers and 911 dispatchers to receive 40 hours of training that teaches them to recognize signs of mental illness so they can identify symptoms in individuals. The programs also cover de-escalation techniques, so that police and dispatchers can refocus on diverting individuals into treatment.

In some places, only Crisis Intervention Team police officers respond to crisis situations, but in others, like the model in Westchester County, a social worker or peer specialist works out of the precinct and co-responds with police officers. The team model works with self- selected staff, so the experienced workers have a deep and skilled understanding and sensitivity to mental illness from the get go.

In addition to training, Crisis Intervention Teams forge stronger relationships between local precincts and community hospitals and mental health centers. The process of admitting someone to a treatment facility is streamlined so that the police don't wait long hours in an emergency room and so that people who are in need of treatment get it immediately.

Who Not Here?

On Feb. 24, experts from Westchester' Crisis Intervention Teams came to New York City to share the success of their model and its ability to increase the safety of the community, police officers and people in crisis, and aid recovery for people with mental illness.

Unfortunately though, the New York City Police Department continued its pattern of refusing to hear proposed solutions or to adopt these new models despite their proven effectiveness in deescalating crises. Department representatives did not show up for the roundtable, organized by Rights for Imprisoned People with Psychiatric Disabilities, or RIPPD, a grassroots organization of formerly incarcerated people with psychiatric disabilities, advocates and family members.

Recently, community residents and members of Rights for Imprisoned People with Psychiatric Disabilities gathered outside the 79th police precinct, where Morales died, and demanded: How can the New York Police Department not implement this program?

Too much is at stake. The list of New Yorkers with mental illness harmed by police unprepared to help them is too long, and includes Earl Black, Rodney Mason, Alan Zelencic, Stephanie Lindboe, Khiel Coppin, Gilberto Blanco, and David Kostovski.

The New York Police Department must do the right thing for New Yorkers with mental illness, their family and friends -- and their own officers. Until the police modernize their tactics, every encounter with a person in psychiatric crisis will continue to be a chance for avoidable tragedy.

Alexandra Smith is a criminal justice advocate at the Urban Justice Center’s Mental Health Project and a member of Rights for Imprisoned People with Psychiatric Disabilities. For more information visit Rights for Imprisoned People with Disabilities.