‘It’s just not designed to do its job’: Will New York reform its state ethics agency?

Skelos, Cuomo & Silver in 2011 (photo via the Governor's office)

This year’s elections in New York saw the issues of public corruption and government ethics reform take centerstage in several campaigns. Insurgent Democratic candidates, some who succeeded and others who did not, challenged incumbent elected officials on their parts in the broken system of corruption prevention and ethics enforcement at the state level that has allowed -- some say encouraged -- rampant corruption and self-enrichment.

Much criticism has been levelled at the state’s Joint Commission on Public Ethics, or JCOPE, a relatively young agency with a lackluster record of keeping watch on wrongdoing in state government. Since the agency’s inception seven years ago, several sitting lawmakers have been indicted and convicted of public corruption. But in most, if not all, those cases, JCOPE seems to have sat idly by as other enforcement agencies eventually stepped in. JCOPE has brought enforcement actions for ethical violations against only two lawmakers in that time -- one in 2013 against former Assemblymember Vito Lopez and then in 2015 against former Assemblymember Dennis Gabryszak. The body does not appear to many as much of a deterrent or enforcer.

Now, with Democrats set to take full control of the state Legislature and legislative leaders signalling a renewed commitment to reform, there’s talk of altering, or even repealing and replacing JCOPE, with some reform-minded legislators eyeing their new opportunity and even some relevant campaign season words from Governor Andrew Cuomo about making the ethics body more independent. Among them are Assemblymember Tom Abinanti, who wants to reform the agency’s membership, and State Senator Liz Krueger, who has proposed eliminating JCOPE and creating an entirely new agency from scratch.

Good government advocates are pushing for a soup-to-nuts reimagining of ethics enforcement. At minimum, they say, there should be changes to how JCOPE commissioners are appointed and that the agency should be given more teeth. The best-case scenario? Do away with JCOPE entirely and replace it with an entity as close to completely independent of political interference as possible.

JCOPE was created in 2011 during Cuomo’s first term, after he came into office promising to wipe clean the rot that had infected state government. Part of a deal with a hesitant Legislature, the agency was charged with overseeing lobbying activities and ethics violations by members of the state Assembly and Senate, the executive branch, dozens of state agencies, and candidates for elected office. It’s composed of 14 commissioners who serve five-year terms -- six appointed by the governor and lieutenant governor, three appointed by the Assembly speaker, three appointed by the Senate majority leader, and one each appointed by the minority leaders in both legislative chambers. The governor also appoints the chair of JCOPE while its executive director is chosen by the commissioners.

To advocates, JCOPE’s structure is plainly at the root of its problems. “The fundamental problem is, if you don’t have independent enforcement of the law, it doesn’t matter how good the laws are,” said Blair Horner of the New York Public Interest Research Group. “While that’s not a bumper sticker issue, it’s not the sexy ethics issue to talk about, it is the critical one. The cornerstone of effective ethics enforcement is the independence of the agency that deals with it.”

Advocates and reform-minded elected officials have argued for years that JCOPE commissioners cannot be expected to conduct robust investigations of the very institutions, entities, and individuals that appoint them. JCOPE’s current executive director Seth Agata, a former aide to Cuomo, was a particular target of that criticism during the election. Cuomo’s Republican opponent, Dutchess County Executive Marc Molinaro, repeatedly called on Agata to step down over having failed to adequately scrutinize the executive chamber, particularly after the corruption conviction of Joe Percoco, a former top aide to Cuomo, who was found to have used his executive chamber office while working on Cuomo’s first reelection campaign.

In their only debate of the race, even Cuomo conceded that he would prefer to see a more independent JCOPE. “I believe we need more independence on JCOPE, I believe we need totally independent appointees and not necessarily representatives of both houses [of the Legislature],” he said. “I’d be open to a number of configurations, but they’d have to be independent. I’d have the attorney general involved; I’d have the chief judge involved in appointing the members.”

As he often has, Cuomo indicated his belief that even getting the Legislature to agree to creating JCOPE was a significant lift, and he added that it provided an opportunity to push further, having cracked the door open.

In the Democratic attorney general primary race as well, Fordham Law professor and anti-corruption crusader Zephyr Teachout led the charge in calling for Agata’s resignation, inflamed in part by JCOPE’s investigation and subsequent clearing of Sam Hoyt, a former state economic development official who was accused of sexual harassment and assault by a woman who said he helped her obtain a job at the state DMV. Hoyt was previously a long-serving member of the Assembly and was also investigated for sexual harassment while in office, and was later disciplined for having an inappropriate relationship with an intern. He was recruited after that by the Cuomo administration.

Public Advocate Letitia James, who went on to win the attorney general seat, initially took a softer position on JCOPE but eventually too joined Teachout in calling for Agata to step down, as did Rep. Sean Patrick Maloney, who was also in the race. Former Verizon executive Leecia Eve, who worked with Agata in Cuomo’s administration, was the only Democratic attorney general candidate not to issue that demand but did say that JCOPE should be scrapped and a new agency created from the ground up.

[Read: Agenda 2019: High Hopes for Long-Awaited Reforms]

There have been bills introduced in the state Legislature that would accomplish these goals. Earlier this year, Assembly Member Tom Abinanti, a Democrat representing parts of Westchester County, proposed restrictions to JCOPE’s membership. His bill would prohibit an individual from serving on the commission if they had been a registered lobbyist, elected official, state officer or employee, or a legislative employee within the previous ten years. “We should ensure that no member of JCOPE is inclined to act preferentially for or prejudicially against any subject of a JCOPE inquiry,” Abinanti said in a phone interview.

Abinanti said he was open to the idea of potentially scrapping the agency but said his bill was a necessary half-measure in the absence of broader action. “My bill is a more practical approach that, so long as we have JCOPE, we have to make some reforms and we need to make sure that the members of JCOPE do not have any relationships with the people who might become the subjects of their inquiry,” he said.

The office of Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie, a Bronx Democrat, did not respond to a request for comment. Senate Democratic spokesperson Mike Murphy said, “There was much done by the previous majority in furtherance of Senate Republicans’ partisan agenda and we expect to reform those inequalities to create more fairness,” likely referring to the fact that the Senate Republicans will still maintain control of a majority of the chamber’s appointments to JCOPE even after Democrats take the majority.

Good government advocates agree that, in the absence of a new independent agency, the Legislature should make fixes to JCOPE’s problems, which are many. Besides the perceived conflicts of interest in appointments, the agency is notoriously opaque to the public. It does not release the details of investigations or even say whether an investigation has been initiated or concluded, for which it was recently sued by New York State Republican Party Chair Ed Cox. Its bizarre rules also effectively allow three Republicans out of the 14 members to block a majority vote for an investigation to proceed into a state elected official, said Alex Camarda, senior policy advisor at Reinvent Albany. The law mandates that the majority vote must include “at least two members appointed by the governor and lieutenant governor and enrolled in the individual's major political party, if he or she is enrolled in a major political party.”

“That’s probably the greatest flaw with JCOPE,” Camarda said. And, owing to how the original JCOPE law was written, both parties also retain the number of appointments they can make even if they are not in the majority in a legislative chamber.

“There’s tweaks and adjustments to the current structure or there’s scrap the whole thing and start over,” said Camarda. “The best practice is to start with a nominating pool from which elected officials choose and the candidates that are put into the nominating pool would be put there by an outside body like the City Bar Association or judges, people who are unaffiliated with the targets of ethics investigations.”

Senator Krueger, a Manhattan Democrat, agrees with that sentiment and has proposed a state constitutional amendment to create that independent entity.

Krueger introduced a resolution, co-sponsored by Assembly Member Robert Carroll, a Brooklyn Democrat, at the tail end of the 2018 legislative session that would add a new article on state government integrity to the constitution. It would establish a New York State Commission on Government Integrity to take over the role currently played by JCOPE. The new commission would be made up of nine members -- two appointed jointly by the governor, attorney general and comptroller; five appointed by the state’s chief judge and the presiding justices of the appellate courts; and one each by legislative conference leaders of political parties that are the top-two vote getters in the previous gubernatorial election.

Pursuing a constitutional amendment would also remove Governor Cuomo from the process. Unlike a bill that he could choose to sign or veto, the amendment would have to be approved by both legislative chambers in two consecutive sessions and then be presented to voters as a ballot measure.

“So do I assume [the governor] wouldn’t like this? Yes, probably he wouldn’t like this,” said Krueger, who will be a powerful member of the incoming Senate majority. “He wrote the existing JCOPE language. I don’t think that current model is working and I think we need to fix that...It’s just not designed to do its job.”

Krueger plans on reintroducing her resolution in the upcoming legislative session in January, with a few changes, which her office shared with Gotham Gazette, after consulting with the state’s chief judge and attorney general’s office. The earlier version allowed the commission to remove a legislator from office but the new version does not give the body that authority. Another revision allows the commission to give informal advice, which can then be used by an individual as defense in any potential future investigation.

The bill hasn’t been discussed yet by Senate Democrats and Krueger said it isn’t on the list of priorities for the conference as it meets this week to prepare for January. But Krueger is particularly optimistic that the Legislature will be under added public pressure after this election to move ahead on ethics reforms, both preventative and in enforcement. “I always have said, never waste a good crisis in government,” she said, “and when people have serious doubts about the honesty and integrity of their government leaders, it is a serious problem for all of us.”

She continued, “We depend on federal prosecutors to come in and play gotcha with us to finally get anything done. I’m not opposed to federal prosecutors playing gotcha, I just think the state of New York ought to have a system in place that can self-police, that can investigate, that can find people innocent when wrongfully accused and direct those, where there are findings of bad behavior and guilt, that those people be referred to the appropriate people in criminal justice.”

Another area where JCOPE is thought to be unequipped is in examining allegations of sexual harassment, an issue brought into recent relief by the allegation of forcible kissing brought against Senator Jeff Klein by a former aide, Erica Vladimer. Not only is it unclear if JCOPE has the expertise to examine sexual harassment claims, but there is little transparency related to any investigation that may or may not be happening, nor clarity around whether an accuser is provided information about the status of an investigation.

JCOPE spokesperson Walter McClure declined to comment on the proposals put forward by Krueger and Abinanti. “Any decisions on changes to our enabling legislation or the laws that we have oversight over are up to the Legislature and the Executive,” he said in an email.

It’s unclear whether the governor will back these efforts. On government ethics reform he has a history of promising big but delivering small, something that has left critics wary. As Camarda noted, “The governor told the editorial board of the Daily News that he was going to put into place a database of [economic development] deals, which he could do via executive order or pass legislation. He has not done that.” He also cited Cuomo’s unfulfilled promise to restrict campaign contributions from vendors bidding on state contracts.

The governor also made promises to pursue campaign finance reforms, including closing the so-called LLC loophole, and has repeatedly emphasized banning outside income for legislators as a sweeping ethics solution, even when the corruption has touched his own inner circle, removed from the Legislature. He lauded the recent recommendations of a state panel that would give lawmakers a pay raise while severely curtailing the money they can make from outside sources. Cuomo has been less vocal, however, about the issues within his own administration as highlighted by the scandal-ridden Buffalo Billion economic development program.

The governor’s office also did not provide any concrete proposals for reforming JCOPE when asked for comment. Hazel Crampton-Hays, a spokesperson for the governor, said in an email, “Governor Cuomo will continue to lead the fight on ethics reform to restore confidence in government, and we look forward to engaging with the new legislature to update and refine our laws and identify which new reforms will be most effective.”

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

@samarkhurshid @GothamGazette

On Census Preparations, State Lags While City, Advocacy Organizations & Business Community Move Ahead

(image via New York City's City Planning Department)

This is part of AGENDA 2019, a joint Gotham Gazette-City Limits project

Find the rest of the series here

“It might seem early, but given the challenges that are facing the decennial census in 2020, it’s not early enough,” said Steven Romalewski, director of the mapping service at the Center for Urban Research, CUNY Graduate Center. Advocates, government officials, and members of the business community all agree with that sentiment, that early preparation is essential if New York is to ensure a full accounting of its population in the 2020 Census, wherein the stakes are immense.

The census, the federal government’s constitutionally required every-ten-year count of residents of the United States, forms the basis for each individual state’s electoral representation, both locally and at the federal level, determines levels of federal funding states receive each year, and underpins dozens of human-facing programs carried out by state and local governments. Officials and advocates in New York City have already begun to marshall resources as they prepare for the nearly two-year effort that lays ahead, but the state has yet to pick up its feet despite a looming deadline.

Many view 2020 as a particularly challenging year for the Herculean effort of carrying out the census. Besides the usual logistical challenges of reaching hard-to-count communities, 2020 is set to see lower-than-expected funding from the federal government, a shift towards digital methodology, and the inclusion of a citizenship question, though it is the subject of ongoing litigation spearheaded by New York Attorney General Barbara Underwood. All that comes amid a heightened atmosphere of anxiety among minority and immigrant communities who fear the repercussions of being counted by a federal administration overtly hostile to their interests while already being most likely to be undercounted.

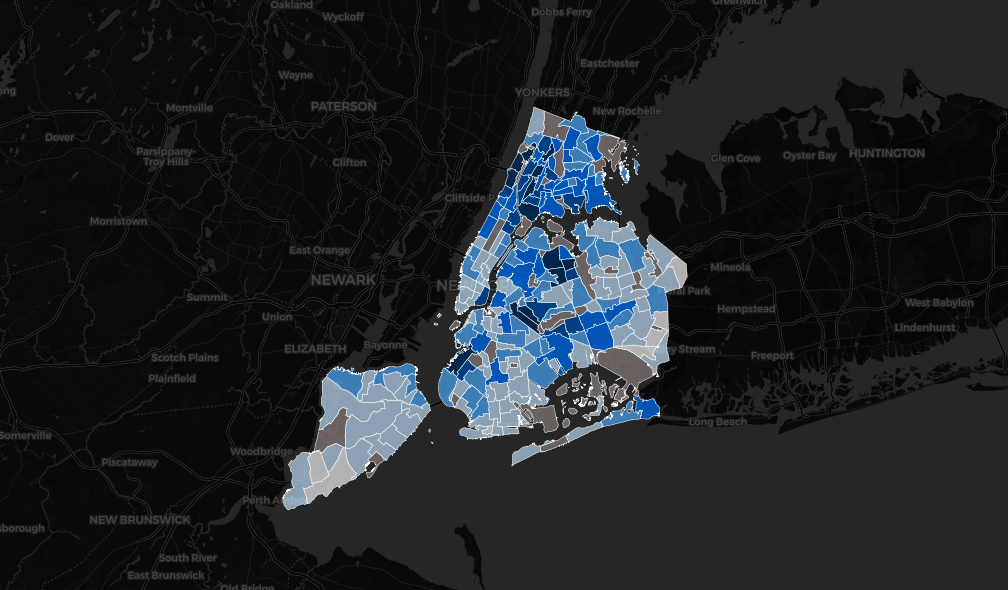

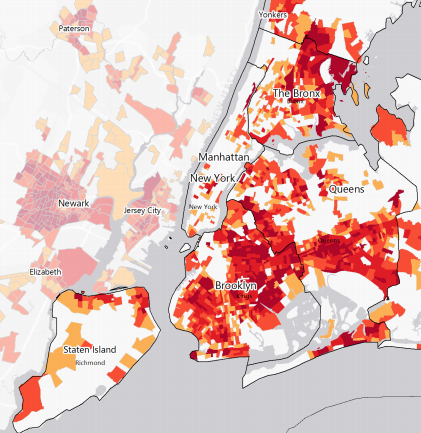

In each census, the federal government has to work hand-in-hand with local counterparts to reach hard-to-count communities, those where at least a quarter or more of households do not fill out the initial census questionnaire sent out by the Census Bureau. In New York State, 75.8 percent of households responded to the 2010 census, according to estimates by the CUNY Graduate Center, which worked with civil rights organizations across the country to create maps of census tracts to identify hard-to-count communities. The rest must then be counted in person by the thousands of enumerators hired by the Census Bureau, a labor- and time-intensive process that includes a lot of door-knocking and also requires additional resources and funding.

Advocates and experts warn that the Trump administration’s underfunding of the Census Bureau and attempt to include a question about citizenship may lead to a grossly inaccurate count, the effects of which will be felt for the better part of the decade before the next census in 2030 and could hit New York, especially New York City, particularly hard. An undercount can cement the problems faced by the most vulnerable members of society -- seniors, children, the homeless, for instance -- and exacerbate them by creating a false dataset based on which government crafts policy and budgets.

City officials already recognize these challenges that lay ahead. Deputy Mayor for Strategic Policy Initiatives Phil Thompson is leading the de Blasio administration’s broad census outreach efforts, coordinating with partners in state government, community-based organizations, and the private sector, which is particularly involved in the current census cycle. Thompson pointed to two main outreach targets: immigrant communities and black communities.

“In immigrant communities, it’s always a challenge to get a good count in New York City because it is so diverse,” Thompson said in a phone interview. “There are so many immigrant communities, which people may not even hear about sometimes. [The questionnaire is] not in their language. They’re new. They get skipped.”

The Census Bureau currently only translates its questionnaire into about 20 languages, he said, and New York City residents speak more than 100. The city has already allocated about $4.3 million to its census efforts in the current fiscal year, ending June 30, 2019, which will be used to conduct outreach through ethnic media, Thompson said.

But the bigger fear among the large undocumented immigrant population that resides in the city is that census answers may be passed on to immigration enforcement authorities, even though that is prohibited under the law. “Now, the law prohibits passing information on from the census to any other agency and individual data is not allowed to be passed on, but folks are scared anyway,” Thompson said.

But the bigger fear among the large undocumented immigrant population that resides in the city is that census answers may be passed on to immigration enforcement authorities, even though that is prohibited under the law. “Now, the law prohibits passing information on from the census to any other agency and individual data is not allowed to be passed on, but folks are scared anyway,” Thompson said.

[pictured: New York City census hard-to-count map, via CUNY Graduate Center Mapping Service]

Black communities, the other main target of the city’s efforts, have had historically low rates of filling out the census, Thompson noted. “That goes for people who live in public housing or in low-income housing. Many people may have an extra person living in the house and they’re afraid that the census comes and does a count of who’s in the household, they may get in trouble...And then some mysteries. We don’t know why middle-income and upper-middle income black people in Southeast Queens don’t fill out the census, but historically they’ve had low rates as well.”

2020 will also mark a major shift in how the census is carried out, with a greater reliance on digital technology. As opposed to the past method of sending out the questionnaire by mail, the Census Bureau will send out a digital code by mail, encouraging people to fill out the questionnaire on the Census Bureau’s website.

When people do not respond, they will be sent a full paper questionnaire to mail back. People can still request a paper questionnaire, particularly if they lack easy access to the internet. “And that’s a challenge because not everybody utilizes iPads and computers,” Thompson said. “Not everyone’s on the internet. So in communities with low broadband access, they are more likely not to fill out the census.”

In response, the city plans to set up help desks at public libraries and schools to facilitate access, with several public-facing city agencies such as the Department of Education and Department of Homeless Services also involved in the effort. The de Blasio administration is encouraging the private sector to provide financial assistance to community organizations and will also put more funding into hiring immigration lawyers at immigrant affairs offices. The city will also hire 13 district office directors to match the 13 offices being set up by the Census Bureau across the five boroughs, and is helping recruit for the 20,000 or so enumerators that the Bureau will hire to conduct door-knocking and outreach in hard-to-count communities in the city. According to the Bureau’s estimates, they will need roughly 44,442 enumerators for the entire New York region. There are also jobs under the city’s Summer Youth Employment Program focused on democracy and the census, training young people between the ages of 16 and 24 to organize in their communities.

“We’re also telling people if you don’t like what’s going on in terms of a lot of this anti-immigrant rhetoric and so forth, the best thing to do is to not go and hide in the shadows but stand up and be counted,” Thompson said, touching upon the challenge involved in convincing people already wary of the Trump administration to trust that administration’s census process.

Community advocates, in particular, are aware of the pressing need to ensure an accurate count. Liz OuYang, coordinator of New York Counts 2020, a statewide coalition of community organizations, said the upcoming census would be a “heavy lift” compared to 2010. “More than ever, community-based organizations are going to be needed as trusted organizations that people can go to in light of the political climate,” she said. These groups are particularly vital in reaching undocumented immigrants who are fearful or skeptical of the federal government.

Ahead of the 2010 census, community organizations in New York City received only about $2 million in total from private sources, OuYang said, leading to an undercount. This time around, the coalition is pushing the city and state to fund phone-banking and door-knocking operations. They are urging legislators to agree to that demand and plan to rally in Albany, the state capital, in March, ahead of the passage of the state budget.

The coalition is also aiding local Complete Count Committees, including by creating a census training webinar for the committee recently launched by Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams and the Brooklyn Community Foundation. “Because of the undercount in 2010 and because of the macro-political climate that we’re in, and the census being allowed to be completed online, you’re going to need a lot of help from community-based organizations,” OuYang said.

The federal government appropriated about $2.8 billion for the Census for the 2018 fiscal year, which ended September 30. But the Census Bureau has requested only about $3.8 billion for the 2019 fiscal year, which most experts and stakeholders believe is inadequate. Across the country there are expected to be 200,000 fewer enumerators, who conduct the on-the-ground follow up, because of the lower funding. What’s more, unlike past census efforts, the federal government appears unlikely to approve a waiver that would allow the Commerce Department to hire non-citizens to act as census enumerators in order to reach hard-to-reach communities. Such a waiver was approved by the administrations of Presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush.

“We don’t know if Trump will do a waiver and if not that’s a problem,” said Deputy Mayor Thompson. “So we’ll have to lean in as a city to get the right people because the most trusted messengers in communities that are fearful are people from the communities.”

In an email, Census Bureau spokesperson Kristina Barrett said the agency was working within the restrictions of the annual appropriations act. “There is not a ban, and we are still pursuing all legal flexibilities provided by Congress to hire the workforce we will need to conduct an accurate 2020 Census,” she wrote. She said the Bureau is allowed to temporarily employ translators under certain exceptions and can hire permanent legal residents applying for U.S. citizenship, people admitted as refugees or granted asylum who have filed a declaration of intent to become a permanent resident and then a citizen when eligible.

To make up for the expected shortfall in enumerators, particularly in undocumented communities, the New York Counts coalition is pushing the state government to ensure adequate funding for counting efforts. A study from the Fiscal Policy Institute, commissioned by the coalition, estimated that need at about $40 million, roughly $2 for each of New York’s 19 million residents. But so far, the state has made no commitment while the city’s $4.3 million is something, but far from adequate. (The city is expected to add more funding in the next fiscal year which begins July 1, 2019.)

“Without funding, community-based organizations are not, that’s the bottom line, are not gonna be able to do full outreach,” OuYang said. “And it takes community-based organizations, trusted organizations in the community to really mobilize people and be the bridge here.”

In the current fiscal year, Governor Andrew Cuomo and the state Legislature approved the creation of a New York State Complete Count Commission, which is meant to study past undercounts and issue a comprehensive action plan for 2020 by January 10, 2019. But with just over a month till its report is due, that commission has yet to be formed, raising concerns that the state is dragging its feet. “I think that the governor needs to prioritize this, this is huge,” OuYang said.

A spokesperson for Cuomo said in an email that the commission is in the final stages of being assembled but did not provide any personnel details or proposed budget numbers. “A complete and accurate count is critical for New York to receive proper representation in Washington and our full allocation of federal funding, and the State is committed to being a full partner in a robust outreach effort so that every New Yorker is counted,” the spokesperson said.

The state has, however, been using data analytics to ensure that the Census Bureau’s Master Address File, which will dictate where the initial census questionnaires are sent in March 2020, is complete. According to the governor’s office, addresses in the MAF were compared to state databases and agency records and hundreds of thousands of corrections and additions were submitted to the Census Bureau for review this past summer. There have also been 40 meetings across the state to encourage the creation of complete count committees.

It’s likely that the governor will provide more clarity about the overall census effort in January at his State of the State speech, where he will lay out his broader agenda for the year. His executive budget proposal with funding numbers will follow soon after.

Thompson, the deputy mayor, said he was optimistic about the state coming through and that operations will likely ramp up with the start of the new year. In the meantime, New York City government and members of the business community are picking up the slack.

“So far New York State hasn’t put up a [funding] number and we were actually helping other towns and cities in New York organize their census operations because the state commission on the census hasn’t met yet,” Thompson said. “We’ve had nice conversations and I’m looking forward to working with the state around this, but right now we’re, I think it’s safe to say, ahead of the state.”

He noted that the New York Banker’s Association had offered to make its locations available to get the word out about the census. “I’m most excited about the responses we’re getting from every sector of the city to come together,” Thompson said. “The business community is very forthcoming.”

The Association for a Better New York, a prominent business coalition in the city, announced on December 3 that it had hired Melva Miller, who was previously deputy borough president of Queens, to lead its census efforts, the broad contours of which had been announced previously. “This is an all hands on deck effort,” Miller said in a phone interview.

ABNY has been marshalling resources for nearly a year to assist New York’s efforts. It has been conducting focus groups in hard-to-count communities, gathering data and information on the obstacles people may face. It also launched a poll last week in those communities “to get an understanding of the census and what that means for them.”

The organization will also pull together a larger messaging campaign, also targeted at particular communities, to urge people to fill out the census on their own, “because unless you can really spell out what the implications of an undercount means to folks, people aren’t excited about it,” Miller said. “No one wants to fill out a form...How can you make it sexy? How can you make it exciting so that people know that this is really critical to the health and the quality of life for all of us, especially New Yorkers?”

Miller noted that the implications of an undercount go beyond federal funding -- New York receives about $80 billion each year -- and a potential loss of representation in Congress.

“There’s voting rights and redistricting implications, there’s public and private research on social and economic issues, and something that folks don’t talk about that probably resonates with the private sector is that having reliable and good data dictates how businesses do business,” she said. “So as companies are doing their needs assessments and assessments of areas in which they might want to relocate or expand, they rely on data that talks about the population. Who lives there, what’s their education level. And then in terms of workforce. People love coming and operating in New York because of our talented and diverse workforce. And quite frankly, we’ve benefitted from programs that assist and support that workforce. And all of that is at stake when you undercount a population like New York.”

“There’s voting rights and redistricting implications, there’s public and private research on social and economic issues, and something that folks don’t talk about that probably resonates with the private sector is that having reliable and good data dictates how businesses do business,” she said. “So as companies are doing their needs assessments and assessments of areas in which they might want to relocate or expand, they rely on data that talks about the population. Who lives there, what’s their education level. And then in terms of workforce. People love coming and operating in New York because of our talented and diverse workforce. And quite frankly, we’ve benefitted from programs that assist and support that workforce. And all of that is at stake when you undercount a population like New York.”

Besides the decennial count, the Census Bureau also does the annual American Community Survey, which delves deeper into subsets of census data and then extrapolates that information to make assumptions about the larger population. “It really has a ripple effect,” said Romalewski of the CUNY Graduate Center, one of the area’s top census experts. “If the count is not done well in 2020, that will have an ongoing impact throughout the decade.”

He did note that there was at least one upside to all the challenges posed by the Trump administration, echoing what has been something of a theme on a variety of political and policy matters. “The silver lining in all of this is that there’s a concerted, coordinated effort early on to make sure people understand the importance of the census and that they participate fully,” he said.

The biggest “what if” factor in the entire census process is the legal battle over the inclusion of the citizenship question. The Justice Department is facing off in federal courts across the country against a broad array of plaintiffs including dozens of states and cities, including New York, immigrant advocacy groups, and the American Civil Liberties Union. Both sides issued closing arguments in late November in a trial in federal court in Manhattan -- other trials are on the horizon in other states -- and a judge is expected to issue a decision within weeks. The U.S. Supreme Court also agreed last month to hear arguments over whether Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross can be deposed over how the decision to include the citizenship question was made.

“The thing I worry about the most is the fear tactics succeeding,” said Deputy Mayor Thompson. But he was undeterred even by the prospect that the highest court in the land could rule against the cities and states seeking to protect undocumented immigrants by ensuring they are counted. He likened it to the country’s history of racial segregation and slavery, which were held up for decades by courts and a Congress that maintained both were legal.

“So just having a Supreme Court go against you doesn’t mean you give up,” he said. “What changed segregation was actually when churches, ordinary Americans said enough is enough. And we have to have that attitude now. We’ll fight back...We have a history of fighting for our democracy. It wasn’t given to anybody, we got it through struggle and we might have to struggle again.”

This is part of AGENDA 2019, a joint Gotham Gazette-City Limits project

Find the rest of the series here

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

@samarkhurshid @GothamGazette

WATCH: Agenda 2019: Movement Expected on Reform, But What Will It Look Like?

(photo: @MNN59)

This is part of AGENDA 2019, a joint Gotham Gazette-City Limits project

Find the rest of the series here

As part of Agenda 2019, the project from Gotham Gazette and City Limits, hosts Ben Max and Jarrett Murphy were joined on Manhattan Neighborhood Network by State Senator Liz Krueger, a Manhattan Democrat, and Susan Lerner, executive director of Common Cause NY, to discuss reform issues and the year ahead. Topics included voting and election reform, government ethics reform, and campaign finance reform. Krueger's new Democratic majority in the state Senate are pledging to work with the Democratic Assembly majority and Democratic Governor Andrew Cuomo to usher through a long list of stalled reforms, but what will actually get done? And what should it look like? Watch:

As part of Agenda 2019, the project from Gotham Gazette and City Limits, hosts Ben Max and Jarrett Murphy were joined on Manhattan Neighborhood Network by State Senator Liz Krueger, a Manhattan Democrat, and Susan Lerner, executive director of Common Cause NY, to discuss reform issues and the year ahead. Topics included voting and election reform, government ethics reform, and campaign finance reform. Krueger's new Democratic majority in the state Senate are pledging to work with the Democratic Assembly majority and Democratic Governor Andrew Cuomo to usher through a long list of stalled reforms, but what will actually get done? And what should it look like? Watch:

This is part of AGENDA 2019, a joint Gotham Gazette-City Limits project

Find the rest of the series here

***

by Ben Max, Gotham Gazette

@tweetBenMax @GothamGazette