On the Bus to Albany for Better New York Voting Laws

One Vote Better NY lobbyist (photo: @NYCVotes)

Two charter buses idling in downtown Manhattan in the early hours of the morning on a weekday would usually be full of mismatched tourists from far-flung states and countries, waiting to gape at the Wall Street bull and his recently-placed female antagonist.

That was not the case for the buses that departed Church Street this past Tuesday morning, which, like their counterpart departing from the Bronx, were full of New Yorkers headed to Albany with a very specific mission: pushing legislators to adopt voting reforms that would make it easier for people to cast their ballots.

The group of about 150 activists, students, and assorted concerned citizens from Manhattan, Queens, Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Syracuse had risen at an hour when most fellow city-dwellers were still sound asleep, steeled themselves with coffee and muffins, and traveled to the state capital as part of the “Vote Better NY” campaign. The effort -- now an annual lobbying day -- was organized by the New York City Campaign Finance Board’s “NYC Votes” initiative, which partnered with schools and civic organizations like Dominicanos USA, CUNY, and the recently founded high school progressive group Coalition Z.

Chloe Baker, 21, a junior studying history at Queens College and interning at the New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG), felt that the trip’s intent was to “get the legislators thinking about [voting reform], and remind them that they work for us,” a sentiment echoed by many of her fellow volunteers.

It’s the fourth year of the annual pilgrimage (Gotham Gazette was also along for the last two). To the chagrin of organizers, the objectives this year are the same as they were the first: to change the laws around voting so that citizens can more easily register and stay registered, and find it more feasible to actually vote once registered.

Those goals are put forward in proposals included in four bills introduced to the Democratically-controlled State Assembly -- they would need passage there, then in the state Senate, and to be signed by Governor Andrew Cuomo. The New York Votes and Voter Empowerment Acts, sponsored by Democrats Michael Cusick of Staten Island and Brian Kavanagh of Manhattan, have some similar language; both would permit pre-registration of 16- and 17-year-olds and allow government agencies like housing authorities to automatically forward voter information for registration.

New York Votes would additionally establish same-day registration with a constitutional amendment (it isn’t permitted under the current state constitution), open polls two weeks before elections for what is known as “early voting,” expand absentee voting, and boost polling place resources and training. Voter Empowerment would establish online voter registration through the Board of Elections and automatically update registration information.

A separate early voting bill, also sponsored by Kavanagh, would, in its current version, establish an early-voting window beginning eight days before an election.

Finally, the so-called preclearance bill, sponsored by Brooklyn Democrat Latrice Walker, would seek to replicate some of the controls previously contained in the Voting Rights Act before it was gutted by the Supreme Court. Counties where 10 percent of the population are racial or language minorities or which have been found to have denied voting rights to protected populations would need to submit any changes in voting-related practical or policy changes to the Attorney General’s office for approval.

The early voting and voter empowerment bills both have versions in the Republican-controlled Senate. The former, sponsored by Democratic Conference Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins, was passed through the election committee and has been sent over to the local government committee. The latter, sponsored by Queens Democrat Michael Gianaris, was voted down, 6-3, in the elections committee less than 24 hours before the activists boarded their buses, including a “nay” vote by one of its own sponsors, Queens Democrat and Independent Democratic Conference member Tony Avella.

Yet what would seem like a deflating defeat was received with cautious optimism by activists, who are happy that the leadership in the Senate -- “where these bills go to die,” was how one NYC Votes staffer put it -- were even publicly acknowledging the ideas.

“Having [Senate Majority Leader John] Flanagan even talking about wanting to know the cost of it is a change in the right direction. Last year it would have been a flat ‘no,’” said Onida Coward Mayers, the NYCCFB director of voter assistance, referring to the Suffolk County Republican’s recent comments citing the potential cost of early voting, while leaving the door open to continued conversations on reform.

The day’s activities began with a rally held by legislators and advocates on the steps of the Capitol building’s famed “Million Dollar Staircase,” where it was moved after rain scuttled plans to hold it in Lafayette Park. After that, the group splintered into 11 teams, each with its own schedule of meetings; the idea was to try to have each legislator who had been open to a meeting hear from at least one of his or her own constituents. “They’re much more interested if it’s someone from their community, because they know that person represents many more at home,” explained Coward Mayers.

The group Gotham Gazette trailed soon found itself in the imposingly bright and bustling Legislative Office Building, where hordes of staffers, lobbyists, and activists tried hard not to run into each other as they shuffled between meetings. First on the group’s schedule was Senator Roxanne Persaud, who had to run out but left an aide, who asked not to be identified, to speak with the six-person delegation. The Brooklyn legislator is one of a handful of Senate mainline Democrats who have not sponsored both of the Senate bills. No Republicans have signed on.

As Amanda Melillo, public affairs officer at NYCCFB, explained that multi-hour lines dissuaded voters from participating in elections, the staffer nodded and spoke of her own experience during last year’s presidential election, saying, “I was out there, I saw the last-minute rush. I understand.” While she couldn’t quite commit to the senator sponsoring the bill, she promised to discuss it with her boss, and ended with the hope that “when we meet next year, it’ll be better.”

A cramped elevator ride and brisk walk through halogen-lit hallways deposited the group at the office of Brooklyn Senator Jesse Hamilton, who greeted Coward Mayers with a hug and spent a few minutes posing for photographs with the activists. Hamilton and his seven colleagues in the IDC, a group that forms a governing coalition with Senate Republicans, are crucial to pushing through the bills that still have a chance in this legislative session, which runs through mid-June.

The group quickly scored their first clear success: Melillo explained the intent of the preclearance measure and had not quite finished asking Hamilton to introduce it in the Senate before he piped up with, “I can do that, that’s not a problem.”

He was a bit less receptive when the volunteers raised the issue of early voting. When Bella Wang, a 26-year-old PhD student at Princeton and former poll worker, brought up voters waiting “one to three hours” to get their ballot, Hamilton said that “that’s only in presidential elections that you get three hours.”

Wendy Odle-Harvey, a volunteer in her fifties whose family moved to Brooklyn from Barbados in the 1970s, chimed in to say that if people vote in any election to find long lines and voting machine problems, they “don’t want to come out to vote for senator, for local races.”

Hamilton promised to look a the bill, but told the group that they’d be best served by “talking to the Republicans, because you’re preaching to the choir.”

Case in point, the group’s next scheduled meeting was with Republican Senator Marty Golden, of Brooklyn, who quickly got into a back-and-forth with Wang when she stated that people with oddly-spelled and hyphenated names often find themselves left off the voter rolls due to human error.

“We have people with names, hyphenated or not hyphenated, voting in several elections” he said, and asserted that there were “people bused in from the Bronx and Westchester to vote in Brooklyn races.” Wang shot back that you were more likely to be “crushed by furniture” than to commit voter fraud, a claim that Golden vigorously disputed. While there have been sporadic claims of voter fraud in New York, Attorney General Eric Schneiderman declared earlier this year that there was not one substantiated incident of voter fraud in New York in 2016.

As Melillo ticked off reasons why New York’s voter turnout is so low - 41st out of the 50 states in the 2016 general election, with 57 percent turnout - Golden asked if it couldn’t be that “people don’t care,” and argued that high immigrant populations and cultural differences led to low turnout in some districts, pointing to “Palestinian and Arab communities” in his own constituency. “Do they vote? No,” he said.

Despite the disagreements, Golden conceded that improvements could be made to the state’s voting procedures, saying “there are a couple of things we can do to help people register and vote, and I’m open to that,” and agreeing to consider the bills. He threw out some of his own ideas, such as making poll workers’ pay non-taxable and getting the MTA to provide expanded service on election days.

Asked about the probability that he would support any of the bills were they to come to a vote, he said “our leader is having conversations about the bill,” but declined to definitively take a position.

Downstairs in the building’s cafeteria, past a group of Army personnel manning a series of small tables covered in military equipment as part of something called Fort Drum Day, the activists took a breather.

“I didn’t really know what to expect…Say ‘I’m a constituent’ and maybe they’ll listen more, but there are a lot of groups here, so sometimes it feels like lip service,” said Natasha Padilla, 38, a Brooklynite who had taken a vacation day to go on the trip, as a group of people in bright green shirts emblazoned with the Airbnb logo chatted quietly 10 feet away.

The final meeting of the day for the group Gotham Gazette followed took its members back through the packed elevators with the electronic voice and to the office of Brooklyn Assembly Member Peter Abbate Jr., who was not available. Aide Joe Brady took his place for a quick discussion that largely consisted of Brady agreeing that there were issues with voting and pledging to discuss the proposals with the Assembly member.

The issue of voting reform is a particularly sensitive one for legislators, Coward Mayers said, because it “taps into their livelihoods. They want to be safeguarded.” If successful, the reforms would shift their voter base, empowering a whole slate of people previously not involved in politics. That prospect can be frightening to elected officials that can pretty much predict the comfortable margin they’ll be reelected with under the current system. Incumbents in New York, where there are no term limits for state legislators, do very well election after election, often running unopposed or with nominal opposition.

For the activists who gave up their weekday to show up at their doorstep, the legislators’ reticence is understandable but misplaced. With “a few million dollars in a multibillion dollar budget,” as Melillo put it, they could bring hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers into the political process. (The state budget that was recently passed totals $153.1 billion in operating funds.)

In a telling exchange with Senator Hamilton, Wang, the PhD student, brought up Minnesota, a state with same-day registration and early voting that also happens to have had the highest percentage turnout in 2016 elections. As Hamilton began to speculate about the reasons Minnesotans may simply have a greater interest in voting, Padilla cut him off.

“They got their people to vote. And it’s really cold there,” she said.

***

by Felipe De La Hoz, Gotham Gazette

@FelipeDLH @GothamGazette

Murky Definitions for Government Entities Undermine Transparency

Gov. Cuomo in Buffalo (photo: The Governor's Office)

When Rockland County Democratic Party Chair Kristen Zebrowski Stavisky fills out her annual state disclosure forms, she consults her husband for question six, which requires the listing of contracts held with a state or local agency held by the filer, filer’s spouse, or unemancipated child.

Evan Stavisky, a partner in the prominent Albany lobbying firm The Parkside Group, after checking with the firm’s lawyer, has told his wife that his company does not represent any government entities. So, for the past six years, Kristen has entered “none” for the question, according to the disclosure documents obtained from the Joint Commission on Public Ethics (JCOPE).

At the same time, between 2010 and 2016, Parkside pulled in more than $1 million from representing quasi-public entities, including four foundations affiliated with city and state universities, three New York City-based public library systems, and a local economic development corporation, according to the lobbying firm’s disclosure filings that can be viewed on the JCOPE website.

One of these contracts, on behalf of the Queens Economic Development Corporation -- which is treated by state law as a public authority -- expired in 2010, so according to filing instructions, Kristen Stavisky was not required to declare it on her JCOPE form for that year. But the other clients -- foundations associated with the CUNY Graduate Center, Queensborough Community College, Queens College, CUNY Creative Arts Team, and SUNY’s University at Buffalo, as well as Brooklyn Public Library, New York Public Library, and Queens Public Library -- fall into an ambiguous zone, defined as local or state agencies in some statutes of New York State law, but not others.

Kristen Stavisky became Rockland County party chair in February 2011, so her first required JCOPE form covered 2010. Political party chairs play a significant role in deciding which candidates run for local and state office, so they are held to the same disclosure standards as elected officials. Meanwhile, Evan Stavisky’s company is paid big money to lobby those same city and state officials on policy and funding matters that impact their clients.

“The reason that party committee chairs are required to disclose potential conflicts of interest because they wield considerable power in relation to elected officials, and they provide the political apparatus to get people elected,” said NYPIRG Executive Director Blair Horner.

As the Stavisky filings show, there is a multitude of quasi-governmental entities that exist in grey area of New York law, and how to classify these entities has been the subject of some debate. A rudimentary search pulled up at least a dozen different definitions for “state agency” and “local agency” in New York State law.

A lawyer for Parkside pointed to the state’s public officer’s law, which defines a state agency as a “state department, any public benefit corporation, public authority or commission at least one of whose members is appointed by the governor, or the state university of New York or the city university of New York.”

While each of the aforementioned Parkside clients rely to some degree on government funding (Queens Library, for example, draws 94 percent of its revenue from city, state and federal sources), have board members appointed by city or state officials, and may serve a public function, as independent 501(c)(3) nonprofits, one could argue these entities do not qualify as a public authority or public benefit corporation. But like more typical government agencies, they are subject to Freedom of Information Laws, according advisory opinions issued by the New York State Committee on Open Government.

A person who willfully files financial disclosure forms incorrectly could face a penalty of up to $40,000 from JCOPE. A spokesperson for the ethics agency -- who is prohibited by law from discussing the disclosure forms of a particular filer -- declined to offer clarification on whether nonprofits associated with CUNY and SUNY were considered government entities according to the public officer's law, but said JCOPE reviews filings and pursues investigations when there appears to be a discrepancy. In other words, the only person who can request an opinion on how a particular filer should answer question six on the JCOPE disclosure form is the filer.

There is also is a lack of consensus on the definition of a “public benefit corporation” and a “public authority,” terms sometimes used interchangeably.

According to Comptroller Tom DiNapoli’s office, public authorities -- which range from transportation agencies like the MTA to bodies created to spur economic development like Empire State Development -- are typically run by boards of directors and are not subject to the same transparency and disclosure as other branches of government. They are also able to borrow money without voter approval, as is constitutionally required of government agencies, a habit that has put the state in fiscal jeopardy.

Public authorities are increasingly enmeshed with state and local government operations, according to the comptroller. They do most of the state’s borrowing and supply revenue streams for the state budget. Sometimes these entities spawn subsidiary public authorities, which are subject to even fewer restrictions. The state’s first public authority, Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, was created in 1921, and more than 1,000 State and local public authorities, and subsidiaries of authorities, have been authorized since.

In 2004 and 2009, in response to a number of investigations into mismanagement, irresponsible borrowing, and questionable financial practices on the part of public authorities and their subsidiaries, attempts were made to streamline the definition and oversight of public authorities.

Then-Comptroller Alan G. Hevesi, raising concerns about “backdoor borrowing,” joined with then-Attorney General Eliot Spitzer to introduce the Public Authority Reform Act of 2004 “to capture all of these entities in one place and impose new rules to govern the conduct of public authorities and their representatives.” The proposed legislation compiled a list of “more than 640” entities, classifying them in A,B, C, and D classes. Class A and B public authorities would be required to adopt specific principles of corporate governance and fiscal integrity. They recommended Queensborough Community College Auxiliary Enterprise Association and the CUNY Research Foundation (two organizations that hired Parkside within the past six years) be classified as “Class B” public authorities.

Based on these recommendations, the Legislature and Governor George Pataki enacted the Public Authorities Accountability Act of 2005, later amended by the Public Authorities Reform Act of 2009, which established the Authorities Budget Office (ABO) and an official definition for “public authority.” The legislation also directed the ABO to maintain a list of state and local authorities, a list that currently does not include CUNY and SUNY foundations, the New York City library systems, or other quasi-governmental nonprofits.

But while the ABO’s office lists 578 authorities, a recent count by the state comptroller’s office found 1,192 state, local, and interstate or international authorities. A footnote in the comptroller’s report addresses this discrepancy: "Due to statutory, regulatory and administrative differences between the Office of the State Comptroller and the ABO, the ABO’s list does not identify certain entities included in this count, such as subsidiaries (which ABO includes with the parent authority), inactive authorities, and college auxiliary corporations."

Government reformers say this ever-morphing patchwork of definitions only serves to confuse the public and obscure conflicts of interests, rather than increase transparency.

“Complexity defeats accountability and complexity defeats democracy. One of the reasons I’m a reformer is to simplify how things work,” said SUNY New Paltz professor Gerald Benjamin. “The purpose of disclosure is for the person who is letting sunshine in to hold people accountable. If the detail of the law prevents transparency from doing its job, then it’s getting in the way of good government.”

While the Staviskys' situation is somewhat unique, this murky territory around what constitutes a government entity creates pitfalls for elected officials and others filing annual disclosure forms.

Furthermore, lax guidelines surrounding CUNY and SUNY nonprofits have led to wasteful spending and, in worst case, exploitation by bad actors. The state is currently facing a crisis of trust in government, according to public opinion polls. In the last year, both the CUNY and SUNY systems were rocked by allegations of financial impropriety involving related nonprofits. Now, more voices are calling for increased oversight of these nonprofits, which, like public authorities and public benefit corporations, are financially intertwined with government agencies and serve a public function.

Notably, two privately-run, deep-pocketed nonprofits affiliated with SUNY Polytechnic Institute -- Fort Schuyler Management Corporation and Fuller Road Management Corporation -- were at the center of federal and state investigations into Governor Andrew Cuomo’s Buffalo Billion economic development program. Former SUNY Poly president and CEO Alain Kaloyeros and Cuomo’s ex-executive deputy secretary Joe Percoco, along with six others, will face trial later this year on charges of bid-rigging, bribery, and extortion.

Parkside’s business with CUNY Research Foundation factors into another ongoing investigation into widespread misuse of funds by CUNY-tied nonprofits by State Inspector General Catherine Leahy Scott. An interim report by the inspector general released last year highlights presidential discretionary funds doled out by the research foundation that are frequently tapped for housekeeping costs, and parties, personal drivers, and club memberships. The report also notes that CUNY-affiliated foundations spent a significant amount of money on lobbyists “engaged in questionable and seemingly redundant tasks,” even though the system employs its own centralized and school-based government relations staff.

“These costs are significant to CUNY, and while they may be warranted in certain situations, appear to be duplicative in several cases. Even at this early stage of the Inspector General’s investigation, it seems clear that these activities warrant scrutiny and that centralization of these services should be explored,” wrote Leahy Scott.

Of $842,275 spent on outside lobbying by the CUNY Research Foundation during the report’s 2013-2015 review period, nearly 20 percent went to Parkside Group, and another 50 percent went to two lobbying firms founded by former Parkside executives, according to year-by-year comparison of the report and JCOPE lobbying disclosure forms. The firms were hired to lobby the Legislature and New York City Council on funding as well as policy matters.

When the report was released in November 2016, Governor Andrew Cuomo, who had been dealing with blowback for the scandals tied to his economic development programs, seized on the news of the CUNY investigation as an opportunity to push for sweeping reform across the state and city university systems, vowing to expand the jurisdiction of the state inspectors general to cover the university-based nonprofits, and calling for these entities to embrace good government practices. Language in the enacted 2017 budget expands the inspector general’s jurisdiction to include CUNY nonprofits, particularly, the research foundation, but notably it does not restore the state comptroller’s oversight over procurement through SUNY non-profits -- a power that was stripped in 2011 to expedite Cuomo’s economic development programs.

When reached by phone, Evan Stavisky, joined by his lawyer, offered a series of evolving explanations for their determination on whether Kristen Stavisky would disclose Parkside contracts, but noted that it was immediately obvious to them that as nonprofits, these clients were not government entities. He did not seek advice from JCOPE.

“Each year, our firm completes 12 separate filings for every single client for city and state regulators, a total of more than 500 annually. Since Kristen Stavisky became chair of the Rockland Democratic Party, our firm has filed 3,000 lobbying disclosures and not a single one has been for a government agency. It is false to suggest otherwise,” said Dan Katz, executive vice president and a general counsel to The Parkside Group, in a statement.

While political party chairs are not prohibited from lobbying the New York State Legislature themselves, they are barred from offering “goods or services having a value in excess of twenty-five dollars to any state agency” and from working on “the adoption or repeal of any rule or regulation having the force and effect of law,” according to a 1992 advisory opinion from New York State Ethics Commission, the first incarnation of JCOPE. The law does not necessarily extend to household members of the chairperson, but filers must indicate government contracts exceeding $1,000 held by a spouse or unemancipated child.

The decades-old regulation, along with most of the state’s modern government ethics law, sprang from a 1986 corruption probe that rocked Mayor Ed Koch’s administration, which landed a Bronx Democratic Party chair in prison, and was marked by suicide of Queens Borough President Donald Manes, who was also implicated in the scheme. The party chair, Stanley Friedman, was a stockholder in a company called Citisource Inc., which benefited from a $22.7 million contract with the city’s Traffic Violations Bureau for traffic agents' handheld computers.

The reforms implemented in the Ethics in Government Act of 1987, which were hailed as a major turning point for government accountability in New York, were intended "to enhance public trust and confidence in our governmental institutions [by strengthening] prohibitions against behavior which may permit or appear to permit undue influence or conflicts of interest,” according to then-Governor Mario Cuomo. Many amendments have been signed into law since.

This question of whether a political party chair can lobby government entities is likely to resurface over Keith Wright, currently the Manhattan Democratic Party chair, who earlier this year accepted a position at Davidoff Hutcher & Citron, LLP, a lobbying and government affairs firm which represents The North Shore Board of Education, a government entity, and NYC & Company, a government-funded nonprofit. Wright, who left his seat in the Assembly in an unsuccessful 2016 congressional bid, was not listed in the firm’s January–February JCOPE filings. A spokesperson for the New York County Democratic Committee said Wright does not perform lobbying duties as part of his new role; he advises clients on government affairs.

The Staviskys maintain that Parkside’s business interests are kept separate from Kristen’s duties as Democratic committee leader and that there is no evidence that Evan or his company has benefited monetarily from the arrangement. Critics actually point to other members of the Stavisky family who wield the type of power likely to attract clients like libraries and SUNY and CUNY foundations. Policy and funding matters concerning these institutions fall under the purview of the Senate’s Higher Education Committee, where Democratic Senator Toby Ann Stavisky of Queens, the mother of Evan Stavisky, is the ranking member.

Parkside’s government-affiliated nonprofit contracts picked up in 2009-2010, the last time Democrats held a ruling majority in the Senate. Toby Ann, a former social studies teacher, chaired the Senate’s Higher Education Committee that year.

At the time, Toby Ann, seeking an advisory opinion, wrote to JCOPE that though she was not required to, she would prohibit her son, but not his partners, from lobbying members of the Senate. Despite calls for a probe from ethics watchdogs, a 2009 advisory opinion from the state's Legislative Ethics Commission deemed the arrangement “appropriate,” the New York Daily News reported.

Correction: A previous version of this article misidentifed the source of a 2009 advisory opinion. In 2009, the ethics advisory agency for state legislators was the Legislative Ethics Commission.The article has also been updated to include a comment from New York County Democratic Committee.

***

by Rachel Silberstein, State government reporter, Gotham Gazette

@RachelSilby @GothamGazette

Activists, Lawmakers Rally for Voting Reform at Capitol

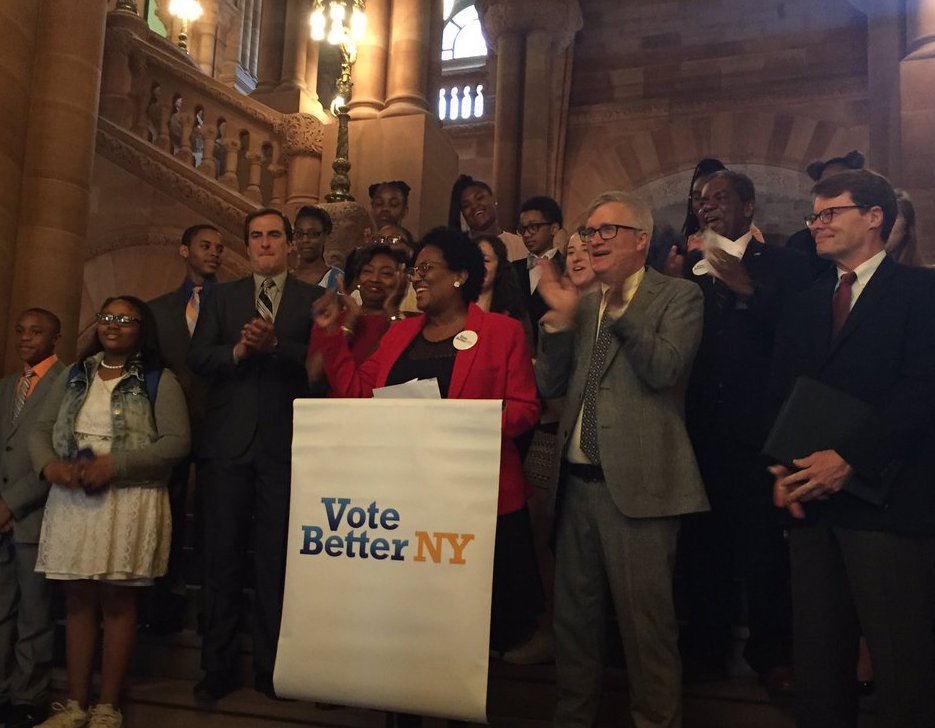

Tuesday's rally (photo: @NYCVotes)

A coalition of electoral reform activists were joined by Democratic state lawmakers during their annual pilgrimage to the New York State Capitol Tuesday to call for legislation that would remove barriers to the ballot and ensure that eligible New Yorkers are provided more opportunity to vote.

“Vote Better NY” seeks common sense changes to New York's voting laws to ensure that more eligible New Yorkers make it to the polls. This year, the organization is advocating for a slew of bills, including early voting, the Voter Empowerment Act, which would streamline the registration process, the New York Votes Act, which refers to automatic registration, as well as new preclearance measures before any additional requirements are added to the current voter registration process.

Senate Minority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins, Senator Michael Gianaris, Assemblymember Latrice Walker, and Assemblymember Brian Kavanagh attended the rally, which was organized in large part by NYC Votes, the voter engagement arm of the New York City Campaign Finance Board, and key member of the Vote Better NY coalition. More than 100 organizers and activists boarded three coach buses from the city early Tuesday morning to rally at the Capitol and then meet in small groups with individual legislators to lobby them toward supporting the voting reform agenda. There has been little movement on such reform in Albany despite a good deal of support and New York’s decidedly antiquated laws.

“Elections have consequences. New York has one of the lowest voter turnout rates in the nation and that should embarrass us,” said Stewart-Cousins, in a statement put out by Vote Better NY. “We should be making it easier to vote and not be putting up roadblocks. That is why I have advanced legislation to enable early voting, and why the Senate Democratic Conference has rolled out multiple pro-voter bills.”

New York has some of the most arcane voter access guidelines in the nation. In 2014, the state ranked 49 of the country’s 50 states in terms of voter turnout. While other states have improved their voting laws to increase ballot access, New York’s abysmal turnout has grown worse for presidential, gubernatorial, and New York City mayoral elections.

Blair Horner, executive director of the New York Public Interest Group (NYPIRG), who participated the rally, said, “New York ranks consistently as one of the nation's worst states in terms of voter participation, driven by our archaic voter registration and election administration systems. Still, young people want to participate in democracy. NYPIRG sees that every day on college campuses across the state.”

In the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election, a new movement to overhaul New York’s voting laws gained support from several high-profile city and state officials, including Attorney General Eric Schneiderman and New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio.

During his 2017 State of the State speaking tour and in his executive budget, Governor Andrew Cuomo proposed a trio of significant reforms: automatic registration, same-day registration, and early voting. Though the governor vowed to “try like heck” to have the reforms included in the state budget, they did not make it into the final policy and spending plan that was announced last month. In an April appearance at the governor’s mansion, Cuomo blamed the Legislature, which he said lacked the appetite for such reforms.

"My point is: There is more to do; there is no political will to do it. Otherwise we would have done it in the budget," Cuomo told reporters during an annual Easter open house.

While increasing voter access should be a bipartisan issue, Republicans in the State Senate have historically blocked electoral reform measures, for fear that the conference would lose its razor-thin majority. After appearing at a rally for the corrections officers’ union Monday, Senate Majority Leader John Flanagan, suggested he may be open to discussing the idea, but couple that sentiment with skepticism about the cost and implementation of any real voting reform.

“It depends how you define voter access; it’s a conversation we should be having regardless,” Flanagan told reporters, citing enlarging the font on the ballot as a sensible reform measure.

When asked about early voting, he told reporters, “Early voting is defined so many ways, is it just one day? I was just joking around that I’m supportive of early voting, just start 5 o’clock instead of 6. It is a serious subject and something we should be talking about, but how do you do that without costing astronomical amounts of money? Our county boards of election are strapped right now.”

***

by Rachel Silberstein, State government reporter, Gotham Gazette

@RachelSilby @GothamGazette